Lately I’ve been reading chapter books with my 8-year-old daughter. We’ve been reading realistic comedy dramas from various American eras, from Ramona Quimby to Junie B. Jones to Judy Moody to Clementine. We’re just starting to (re)delve into the work of Judy Blume.

We’ve also read similar books produced locally such as Philomena Wonderpen by Ian Bone, Billy B. Brown by Sally Rippin and the Violet Mackerel series by Anna Branford.

Many of these stories are great. All of these stories have things to recommend them.

But there is a formula running throughout most chapter books aimed at girls which isn’t doing women any good at all. In fact, in this week heading into the American election, I’m getting pretty cranky about it, because this narrative is having a real world effect.

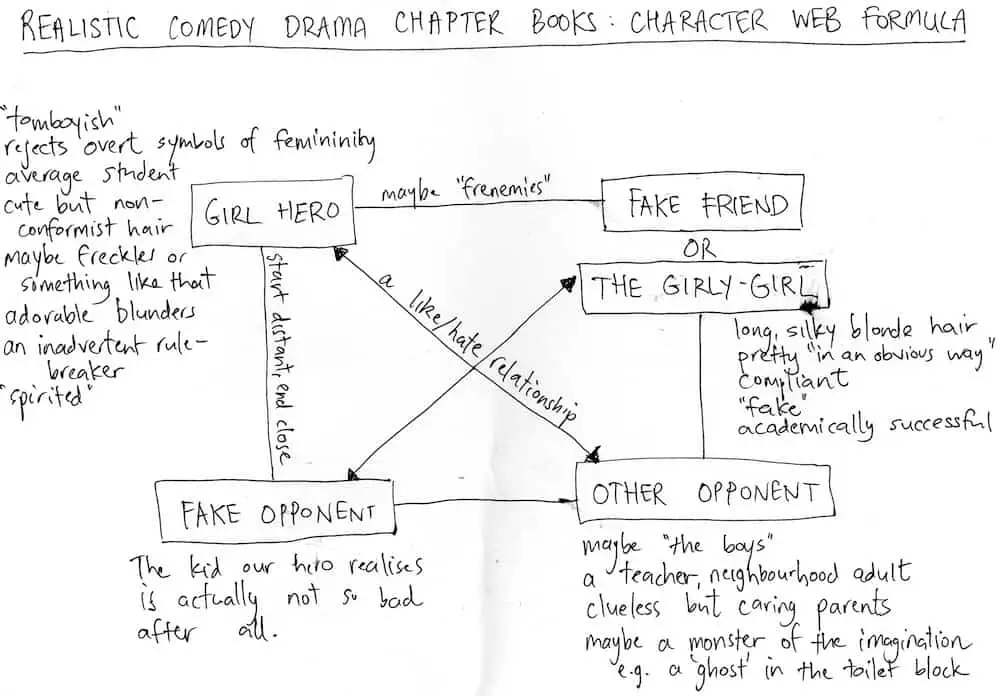

The chapter book formula concerns the character web, which looks like this:

There are variations on this basic plan, of course.

For instance, the girly-girl might actually be the fake opponent.

Considered together as a corpus, this kind of character in middle grade fiction is saying something quite damaging about a certain kind of girl — the young Hillary Clinton archetype. A non-sympathetic character.

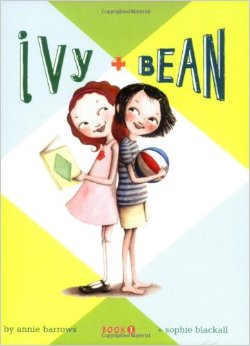

The Mixed Message of Ivy + Bean

The moment they saw each other, Bean and Ivy knew they wouldn’t be friends. But when Bean plays a joke on her sister, Nancy, and has to hide quickly, Ivy comes to the rescue, proving that sometimes the best of friends are people never meant to like each other.

An example of that is the relationship between Ivy + Bean. In their case, ‘tomboyish’ viewpoint character Bean mistakes the girly-girl across the road for someone completely uninteresting. But when she takes the time to know her, Bean realises that Ivy is just as scheming as she is, and because of her good-girl appearance they are actually better equipped to carry out their often quite nasty — but always fun — plans. Various parent reviewers criticise this series for its unpunished bad behaviour, but one good thing about the Ivy + Bean series is that the girls learn in the very first book to look behind appearances.

A possibly quite damaging unintended message is that girly-girls are basically presenting a fake image. And unless a girly-girl reveals a more masculine side, she remains unsympathetic. Ergo, true girly-girls are still horrible. This is femme phobic.

Philomena Wonderpen

Readers are encouraged to despise the girly-girl pinkness of the main opponent but the book covers are largely… pink.

The girly-girl opponent of the Philomena Wonderpen series is a girl called Sarah Sullivan, who the reader knows to hate due to her overtly feminine accoutrements. Her matching pink accessories and her pink bag. Then there’s the way she competes against our imperfect hero and ends up winning the literal ‘gold star’ at the end of camp, dished out by an unsympathetic Trunchbull-esque school principal.

Even though Philomena has all the advantages of a magic wand (her father’s Wonderpen), Sarah Sullivan still wins the gold star — mostly through her own hard work, I might add, though she is also a rich girl and dishes out store-bought sweets.

The more successful a woman is, the more pleasure we take in demolishing her and turning her into a two-dimensional villain. Hillary Clinton’s extraordinary success may only be tempting the God of Trainwrecks to make her our biggest and best catastrophe yet.

Sady Doyle

To dwell upon the ‘fakeness’ of girly-girl opponents, Sarah Sullivan’s ‘store bought’ sweets are depicted by the author in opposition to Philomena’s home-baked treats, and once again, Sarah Sullivan is deemed a ‘fake’, in a way any modern mother should understand implicitly as coming straight from the ad-men trying to persuade us to buy this cookie over that, because it tastes just like a home-baked one, and women are therefore allowed to serve it up. (Because ideally, women are in the kitchen baking genuine cookies, but if we can’t manage that, we must at least make a good attempt at faking it.)

Fakeness as an attribute of hyper-feminine characters is very much related to the ‘women are basically liars’ trope, which has a long and damaging history.

Clementine

Even in the Clementine series, which I do love, overt markings of femininity are punished. This dynamic is set up in the very first paragraph of the first in the series:

I have had not so good of a week. Well, Monday was a pretty good day, if you don’t count Hamburger Surprise at lunch and Margaret’s mother coming to get her. Or the stuff that happened in the principal’s office when I got sent there to explain that Margaret’s hair was not my fault and besides she looks okay without it, but I couldn’t because Principal Rice was gone, trying to calm down Margaret’s mother.

Clementine, Sara Pennypacker

Since hair (and handbags and high-heels) are strong markers of femininity, Margaret the girly-girl opponent is immediately brought down to size, and the reader is encouraged to despise the hysterical mother who is upset about something so frivolous. Putting aside the fact that actually, cutting someone’s hair is a violation of personhood that women have been talking about for decades and which, from boys and men, is actually really unacceptable.

In the seventh book we see the girly-girl character cut down to size by breaking her ankle after insisting on wearing high heels. And so on and so forth. Not so subtle subtext: Clementine is adorable because she is not like one of those girly-girls. She is basically everything we are encouraged to love in a boyish trickster.

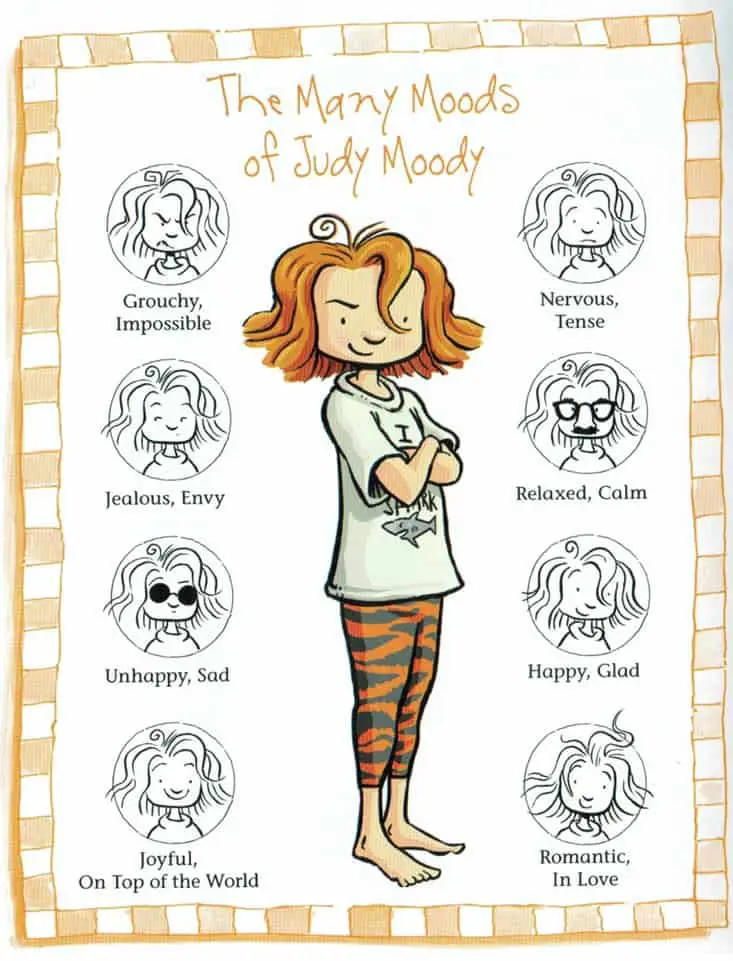

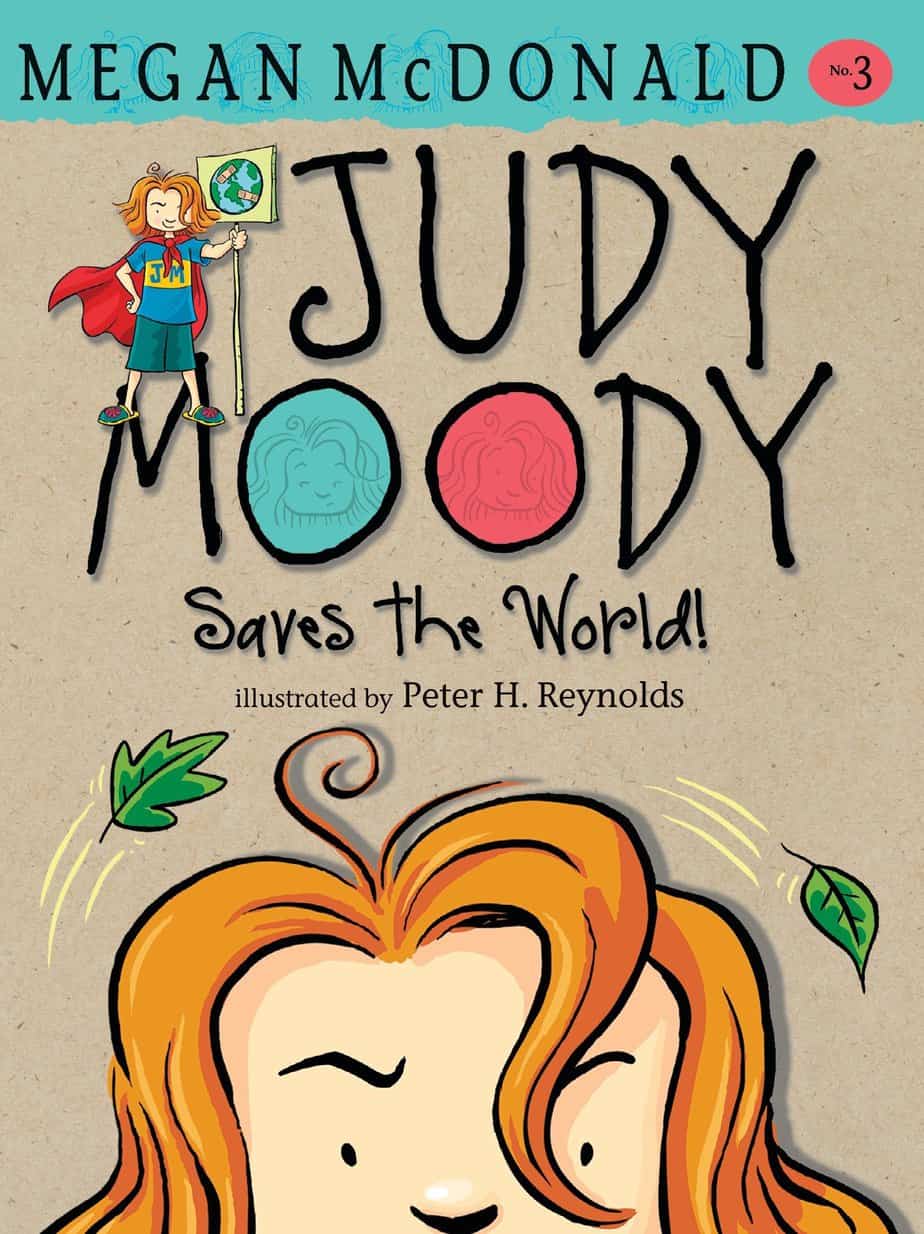

Judy Moody

Judy’s girly-girl enemy is Jessica Finch who at least breaks the mould of blonde bitches by having dark hair. (I suspect the dark hair is a symbolic representation of her dark moods.)

Judy Moody marched into third grade on a plain old Thursday, in a plain old ordinary mood. That was before Judy got stung by the Queen Bee. Judy sat down at her desk, in the front row next to Frank Pearl.”Hey, did you see Jessica Finch?” asked Frank in a low voice.”Yeah. So? I see her every day. She sits catty-cornered behind me.”

Judy Moody Gets Famous! by Megan McDonald

‘Cater-cornered’ means to sit diagonally behind someone, but the common pronunciation gives me the feeling that ‘catty’ is supposed to be a sexist pun. (When women are compared to cats it’s because cats don’t ‘fight fair’. They hiss and spit and posture, and will scratch you with their long ‘nails’.)

We are encouraged to hate Jessica Finch because she is the Queen (Spelling) Bee. We are encouraged to root for Judy’s defeating her mostly because Judy is the viewpoint character but also because Jessica’s presentation is ‘perfect’ — she sits up straight in class and doesn’t have a single hair loose from her high ponytail.

We are also encouraged to hate Jessica Finch because she tries hard, much as Donald Trump criticised Hillary for preparing for the second 2016 presidential debate:

“I have spelling posters in my room at home,” said Jessica. “With all the rules. I even have a glow-in-the-dark one.”

“That would give me spelling nightmares. I’ll take my glow-in-the-dark skeleton poster any day. It shows all two hundred and six bones in the body!”

“Judy,” said Mr. Todd. “The back of your head is not nearly as interesting as the front. And so far I’ve seen more o fit today than I’d like.”

Judy Moody Gets Famous! by Megan McDonald

Obviously, our siding with Judy is helped by the fact that both girls were talking but only Judy gets reprimanded by the teacher authority figure.

A positive aspect of the Judy Moody series is that Judy is allowed to express a wider range of emotions, including anger. But mostly she displays spite, and actually ‘moody’ itself is a highly gendered word. Boys are not called moody for displaying the exact same range of emotions. (And yes, I acknowledge there is also a — completely different but still sexist — problem, concerning the narrow range of allowable emotions in boys and men.)

Junie B. Jones

Like Clementine, Junie B. Jones has a loving relationship with her school principal, owing to her pranks being adorable and the principal being a caring type. (In this post I make the case that Junie B. is a fictional representation of an ADHD phenotype child.)

Junie’s girly-girl enemy is Richie Lucille. The reader knows immediately that Lucille is horrible and unsympathetic because she has long blonde hair tied up in a perfect ponytail, whereas Junie B. looks rough and tumble and doesn’t care about neatness. She is also unlikeable because she is rich. (She has unearned power.)

Billy B. Brown

By now it should be clear that messy hair is prerequisite for empathetic girl heroes.

Billie B. Brown has two messy pigtails, two pink ballet slippers and one new tutu.

The Bad Butterfly by Sally Rippin, opening sentence

It’s almost as if the girliness of the ballet outfit has to be neutralised by the messy hair. The messy hair says, “I’m wearing ballet clothes because I’m doing ballet, but don’t let that fool you into thinking I care about what you think of me.”

Billie’s best friend is Jack. Billie and Jack live next door to each other. They do everything together. If Billie decides to play soccer, then Jack will play soccer too.

The Bad Butterfly by Sally Rippin

Rippin avoids much of the ‘girl drama’ by making Billie a ‘guy’s gal’, basically. Billie’s close friendship with a boy elevates her social status.

The only real gender subversion here is that Jack learns ballet just as Billie plays soccer. This is pretty radical and modern, and it’s easy to overlook the other side.

Because once again we have the horrible girly-girl enemy. This girl is called Lola. Once again she is drawn (by illustrator Aki Fukuoka) with her blonde hair in a perfect bun. She closes her eyes and holds her nose in the air, as if no one else matters.

The message for young readers is that being a girl is fine and girls can do anything they want … so long as they are not too much of a girl. This femme phobic message works in silent opposition to the feminist ‘girls (and boys) can do anything’ intent.

Frenemies: A feature of girl fiction but not in books for and about boys

I have also read the Wimpy Kid books and others like it, and it seems the very concept of ‘frenemy’ is specific to books aimed at girls. There is no frenemy in Wimpy Kid — Rowley is a genuine WYSIWYG friend. Fregley is an out-and-out comedic archetype and the girls are somewhat complicated but one-dimensional opponents. These heterosexual boys don’t like the girls as people but they’re starting to feel inevitable adolescent attraction. The most popular books among boy readers are both reflecting and reinforcing a completely different but equally problematic dynamic — a discussion you can find elsewhere.

In fiction aimed specifically at girls, however, we often see frenemy dynamics. This is an outworking of a culture in which the allowable emotional spectrum for girls spans between friendly and neutral. Anger, distaste, disgust is not generally not allowed from girls.

So we have these girls who trick the adults into thinking they’re perfect but actually they are horrible: a sexist variation on the trickster archetype. The reason this is sexist is because the prevalence of these girls suggests, to widely-read kids that:

- Only girls are able to pull this particular trick off

- Boys are all surface and no depth — boys speak their minds and you always know exactly what you’re going to get.

- Girls are basically liars.

- The worst girls are the prettiest ones. And by ‘pretty’ I mean the girls with the most feminine accoutrements. The more feminine a girl is, the more likely she is to be fake underneath, in a direct correlation.

Hillary Clinton has a unique talent to make people viscerally angry. Just look at the footage from Trump rallies: supporters carry “Lyin Hillary” dolls hung from miniature nooses, cry “Lock her up” and “Hang her in the streets”, and wear Trump That Bitch T-shirts.

Sady Doyle

Boy Tricksters, Girly-girl Tricksters

There are plenty of boy tricksters but they are presented in a completely different way.

Boy opponents, for example, arrange to beat someone up, after school, behind the bike sheds, but we aren’t inclined to call him ‘scheming’ for arranging the fight outside the range of adult supervision.

Boys take girls’ dolls, attach them to kite tails and send them sailing into the air, but boys aren’t schemers — they are simply having fun.

The bully-boy characters in children’s stories are not raking in all the academic awards. The fact that girly-girls also know all the answers is one more reason for the readers to despise them. We don’t like women who have all the answers.

The lesson is clear, and has been reiterated in countless hacky comedies about cold, loveless career women ever since. Success and love are incompatible for women. For a woman, taking pride in her own talents – especially talents seen as “masculine” – is a sin that will perpetually cut her off from human relationships and social acceptance. She can be good, or liked, not both. The only answer is to let a man beat her, thereby accepting her proper feminine role.

Sady Doyle

Feminine Girl Opponents Are Always Brought Down A Peg

When the girly-girl gets water dumped all over her (accidentally on purpose), or her pretty dress covered in ink, the reader is encouraged to revel in schadenfreude. It’s not just that the girl hero manages to come out on top — punishment usually focuses on ruining the very thing that stands for femininity.

Don’t forget that punishing female characters in children’s stories has a long history. Below, the Wicked Witch melts. The Wicked Witch is truly wicked, not just an annoying perfectionist classmate with frilly dresses and bows in her hair:

Salirophilia is a sexual fetish or paraphilia that involves deriving erotic pleasure from soiling or disheveling the object of one’s desire, usually an attractive person. It may involve tearing or damaging their clothing, covering them in mud or filth, or messing their hair or makeup. The fetish does not involve harming or injuring the subject, only their appearance.

Salirophilia, Wikipedia

Wet: In Hollywood story conferences, suggested alternative to nude, as in: “If she won’t take off her clothes, can we wet her down?” Suggested by Harry Cohn’s remark about swimming star Esther Williams: “Dry, she ain’t much. Wet, she’s a star.”

Ebert’s Guide to Practical Filmgoing: A Glossary of Terms for the Cinema of the ’80s

I would argue that Hilary Clinton irritates people not just because of her gender, but because we simply can’t process her narrative. There are no stories that prepare us for her trajectory through life and, therefore, we react to her as if she’s a disruption in our reality, rather than a person.

We love public women best when they are losers, when they’re humiliated, defeated, or (in some instances) just plain killed.

Sady Doyle

It Didn’t Start With Ramona Quimby And Susan Kushner

As Doyle explains, this view of femininity goes back as far as Greek mythology and perhaps even back into the Paleolithic era:

Aversion to successful or ambitious women is nothing new. It’s baked into our cultural DNA. Consider the myth of Atalanta. She was the fastest runner in her kingdom, forced men to race her for her hand, and defeated every one of them. She would have gotten away with it, too, if some man hadn’t booby-trapped the course with apples to slow her down, which is presented as a happy ending. By taking away her ability to excel, he also takes away her loneliness. Then, there’s the story of Artemis and Orion: He’s the most handsome hunter in all Greece, and she’s the Virgin Goddess of the Hunt, who’s ready to get rid of the “virgin” portion for him. Until, that is, her jealous brother Apollo tricks her into an archery contest – she’s so proud of her aim that she lets Apollo taunt her into shooting at a barely visible speck on the horizon and, therefore, winds up shooting her lover in the head.

Sady Doyle

You see it again in the Bible and actually my high school classics teacher had this quote from Pericles on the wall as if it were a maxim to live by:

[I]njunctions against female self-expression or fame are everywhere in ancient history. The Christian New Testament “[suffers] not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man;”Pericles wrote that the greatest womanly virtue was “not to be talked of for good or evil among men”. In the colonial United States and Britain, women who talked too much and started fights were labelled“common scolds” – recommended punishments included making them wear gags or repeatedly dunking them in water to simulate drowning.

Sady Doyle

Boyish Tricksters Are Heroes; Girlish Tricksters Are Punished

[T]hough Clinton activates the darkest parts of her critics’ sexual imagination, our yearning for her downfall goes beyond even that. It’s not just that her success makes her unattractive or “unlikable”, it’s that, on some level, we cannot believe her success even exists. You hear that disbelief in the frantic insistence of certain Sanders supporters that the primary was “rigged”, simply because Clinton won it. You hear it when Trump sputters that Clinton “should never have been allowed to run”, making her very presence in the race a violation of the accepted order. You can hear it when pundits such as Jonathan Walczak argue that even if Clinton is elected, she should voluntarily resign after one term “for her own good”. (Also, presumably, good for George Clooney, whom Walczak offers up as a plausible replacement.) Even when we imagine her winning, we can’t imagine her really winning. Unadulterated female success and power, on the level Clinton has experienced, is simply not in our shared playbook. So, even when a Clinton victory is right in front of our eyes, we react, not as if it’s undesirable, but as if it is simply not real. And the thing is, it might not be. Or at least, it might only be temporary: the rise before the big, spectacular, sexism-affirming fall.

Sady Doyle

The caveat in chapter books is that ‘tomboyish’ girls, like boys, can also get away with anything. It’s the particularly feminine way of being that is not acceptable.

#NotAllChapterBooks

Violet Mackerel

This is where I give a shout out to the Violet Mackerel series by Anna Branford.

Violet is kind, inquisitive, creative, understanding, thoughtful and loyal. The author avoids the girly-girl frenemy dynamics and instead focuses on Violet’s relationship with her hippie family and to the natural world around her. Her ‘opponent’ might be her mother, who meets a friend at the mall and bores Violet talking about the price of petrol, for instance. The conflict is not contrived. We do still have, though, a teenage girl snarker in Nicola, the older sister.

Admittedly, this makes for quieter plots with less Bestseller appeal.

Illustrator Elanna Allen dresses Violet in practical clothing and Violet sometimes has quite neat hair, other times quite messy. The covers of this series are not heavily pink, which I find ironic given the pinkness of all the other books implicitly criticising pinkness.

Fancy Nancy

Fancy Nancy is another interesting case because this is a character who embraces all of those feminine accoutrements vilified in most chapter books.

For pedagogical reasons, I’m sure, these books also teach young readers ‘fancy words’, which Nancy uses with full explanations for the young readers. In other words, there are many ways of being fancy, and one of those ways is to be smart.

There are also lots of standalone books about different kind of girls, but it’s the bestselling series which are the most widely read and therefore the most influential.

Real World Consequences of the Female Maturity Formula In Storytelling

I have previously written about the way in which girls and women in popular stories are consistently portrayed as ‘the only sensible’ one in the room. Typically, the girl is more of a swot, more organised, more witty than the ‘everyday boy’. We see it all sorts of narrative for both adults and children:

- Everybody Loves Raymond (the long-suffering wife)

- Harry Potter (Hermione)

- Calvin and Hobbes (Suzie)

- Big Nate series (Gina, and also the female teacher Mrs Godfrey, who is far more studious about doing her actual job as teacher than the laid back Mr Rosa.)

- Toy Story

- Black Books (Fran, when it suits the plot)

- The I.T. Crowd (Jen, when it suits the plot)

- The Simpsons (Marge and Lisa)

- Futurama (Leela)

- etc.

At first glance, to the uninitiated, this might seem like sexism indeed… but against men. After all, isn’t it good for women’s rights that women are consistently smarter than the men?

No.

- These women are the sidekicks, not the heroes. They start and end the story as sensible; the character arcs happen to the men. You can’t be the hero of a story unless you undergo some sort of character arc. This makes men the main characters of the stories.

- These women are motherly. When the only role for the girl is the motherly type, we end up thinking that’s the only role she’s good for.

- While these motherly types are allowed smart comebacks (a la Suzie from Calvin and Hobbes), they are are often limited to sarcasm. As often as not they are in fact completely humourless, adding to the cultural stereotype that ‘women just aren’t funny’. This sensible, parental role suits the straight ‘man’ more than it suits the funny ‘guy’.

But more disturbing than any of these points are the very real political consequences, as described below at a feminism and linguistics blog, in a discussion about the recent English election:

Powerful women are resented in a way their male equivalents are not; the more authoritative a woman sounds, the less likeable a lot of people (both men and women) will find her. But you might think the current situation calls that analysis into question. If we’re so uncomfortable with women taking charge, how have we ended up in a situation where women are the most credible challengers for the top jobs in British politics?

One answer to that question invokes the concept of the ‘glass cliff’. In politics as in business, women are more likely to be chosen as leaders when an organisation is in serious trouble and the risk of failure is high. In that connection it’s interesting to recall one of the phrases used about Nicola Sturgeon last week—‘the only grown-up in the room’. Since then, other women, including Theresa May and, in the wider European context, Angela Merkel, have also been described as ‘grown-up(s)’. Though the term itself isn’t gendered, I’m beginning to think the metaphor is: it’s a reference to the most culturally familiar and acceptable form of female authority, that of adult women over children. When the men are responding to a crisis by throwing their toys out of the pram, it’s time for Mummy to sweep in and clean up their mess.

language: a feminist guide

For more on this topic but from an American perspective, listen to Slate’s Double X Podcasts: The Powerfrause Edition, in which Angela Merkel, like Theresa May, also swooped in to power after a German political crisis.

So whenever the girl character swoops in to save the boys with her book learning and smart ideas (a la Monster House, Paranorman, Harry Potter), what we’re really seeing is the Glass Cliff effect.

We might also call it the Happy Housewife view of female politicians:

I have heard many women (and some men) say that they want to see more women in power because women would make the world a better place, lift the tone of parliaments and be all-round kinder to the planet. Some go all quasi-spiritual on me, wittering on about female energy and our goddess-given nurturing nature. This has always struck me as the happy housewife model of leadership, where female leaders whiz around cleaning up the men’s mess, leaving the world all sparkly, clean and sweet smelling. It sounds like it’s a compliment but, in fact, it is a burden.

Jane Caro, after the first 2016 Trump-Clinton debate

RELATED CONTENT

- Hillary Clinton deserves credit for her marriage, not insults

- How could sexism hurt Clinton in debates? These female high school debaters know

This view dictates that women must be better than men before they can aspire to leadership, that they must offer something special and different or they have no right to take the top job. Frankly, it sets us up for failure because it sets a higher standard for female leaders than for their male counterparts.

Please don’t mistake this for ‘girl power’. And definitely look out for it in your own country’s politics.

EDIT: Fast forward to 2019 and see Elizabeth Warren become the new Hillary Clinton.

A New Vision For Chapter Book Series Aimed At Girls

Could we change the character web template and still engage young readers? Here’s what I’d love to see:

- More imagination when it comes to dreaming up opponents. Perhaps this is where fantasy shines. Fantasy, unlike realistic drama, is open to all sorts of monsters, ghosts and ghouls and does not need the girly-girl frenemy/enemy. However, as number 2 in the Ivy + Bean series shows (The Ghost That Had To Go), fantastic imaginings can be included even in realistic fiction.

- More complex boy characters. I’d like to kill the stereotype that girls are fake and wily while boys are shallow and simple and unencumbered by complex social difficulties. If writers think they’re reflecting realities, by exaggerating them for comedic effect they are also reinforcing them. Is it possible to model good relationships while still including sufficient tension between characters? (Don’t tell me that these stories shouldn’t be didactic, because they already are.)

- In real life, girly girls are not usually the enemy. The girl with the neat hair is probably sitting quietly in the corner doing her work. I know it’s tempting to write only about the Clementine/Ramona/Junie B. wreckers of this world because these girls are propelled into action by their very nature, but there is an invisible majority of girl readers out there whose compliance and hard work are not only invisible, but actively punished throughout children’s literature. Let’s change that. Because it’s affecting how the actual world is being run.

In stories as in real life girls and boys are held to different standards. How does this play out in children’s literature?

There was a little girl

a poem written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Who had a little curl

Right in the middle of her forehead.

And when she was good

She was very good indeed

But when she was bad

She was horrid!

Contrary to popular belief, the above is not a Mother Goose rhyme but a poem. However, I remember its inclusion — slightly modified — in a book of nursery rhymes from my own childhood.

When I recently ordered the box set of Judy Moody by Megan McDonald for my daughter I was reminded of that rather awful poem, and I wouldn’t mind betting the series illustrator has been inspired by Longfellow, because the curl on the forehead is an enduring feature of Judy Moody’s character design.

‘Good girls must be very, very good or else they are horrid, whereas boys behaving badly are seen to be merely displaying masculine traits’, writes Carolyn Daniel in Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature. While acknowledging that things have changed since the Victorian era, ‘giving way to a generally more therapeutic style, much contemporary fiction still reinforces traditional stereotypical gender roles.’

There is another nursery rhyme from the early 1800s that epitomises our view of what boys and girls are made of — with gender essentialist neurosexism working in both direction:

What are little boys made of?

Snips and snails, and puppy dogs tails

That’s what little boys are made of !”

What are little girls made of?

“Sugar and spice and all things nice

That’s what little girls are made of!

At first glance this poem seems to have been written in a way that favours girls and makes girls’ lives easier. Instead, this poem is terrible for girls (as well as for non-‘boyish’ boys), because as Daniel describes:

There is a sociocultural leniency toward the bad behaviour of boys. Boys are, after all, made of slugs and snails and puppy-dogs’ tails, and they are culturally expected to be naughty, to get dirty, to wriggle and not be able to sit still, to not make rude noises, to fight and swear. And for this they are judged to be “just being a boy” or “a real boy”, one who will grow into a real man. Concomitantly girls must be good. And, in order to become good girls they must be carefully controlled and constantly monitored.

For consideration

- What if Peta Rabbit were a girl and her brothers Flopsy, Mopsy and Cottontail were the good little bunnies who stayed at home?

- Is there a female version of Winnie-the-pooh, who is obsessed over excessive and sweet food in a humorous way rather than as a slight on her character?

- Would John Moody work as a concept (rather than Judy Moody)? Is there a male equivalent in children’s literature? There are plenty of mischievous boys, but what about ‘moody’ ones, allegorically named as such, because their emotions are such an important part of their character? (Johnny Cranky, Sam the Surly etc.?)

- Is stereotypical bad behaviour in girl characters e.g. preening and asking for things she shouldn’t have and talking rudely to (and about) others, perceived as worse than stereotypically boy behaviour e.g. standing up for oneself by using physical violence and threats?

The Hermione Archetype

This is the personality type most likely to drive the action in a small group of heroes. ‘She was the best at playing villains. ‘The Poppys of this world often have to learn to relax, to accept help, and to accept other people’s opinions even when other people aren’t as smart as them. Poppys of this world quite often have red hair, for some reason. Either that or ‘unruly’ in some way.

Hermione is probably a young teenager (or adolescent), and if she is part of a series, she will probably ‘calm down’ a bit with the ‘bossiness’ before she reaches the late teenage years, morphing into a calm, capable woman.

Hermione Granger from the problematic Harry Potter series by the problematic TERF is the little mother who organises everyone and also annoys the boys, but who eventually justifies her inclusion in their tight-knit group because she is so very capable, and ends up being the engine behind solving the story-worthy problem/mystery.

Jenny from Monster House is very much based on Hermione, and like Hermione, has two boy sidekicks who are very similar in turn to Harry Potter and Ron Weasley.

SEE ALSO

The Female Maturity Principle In Storytelling

Australian writer John Marsden did write a picture book about a naughty girl. It’s called Millie. Have you heard of it? If not, there may be a reason for that; it hasn’t found longterm resonance.

Storytellers are often told to give their characters moral shortcomings (ie. a way in which they treat others badly). It’s worth considering as we write our character (and form opinions on other people’s fictional characters) whether we are holding the girl characters to higher standards of likeability.