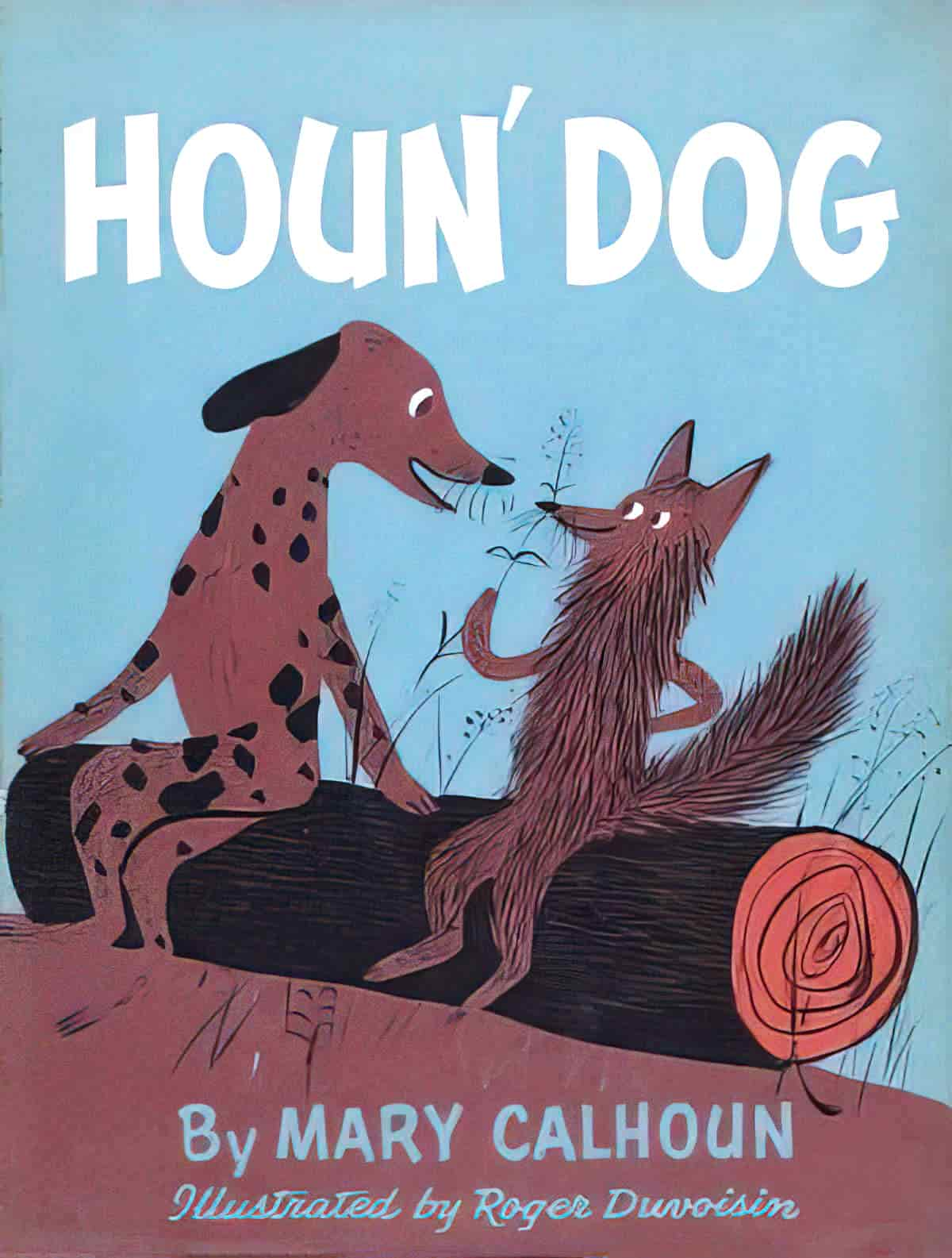

Houn’ Dog by Mary Calhuon and Roger Duvoisin is a children’s picture book about fox hunting for sport. In the picture book it’s called ‘fox racing’, and the author avoids the realities of fox hunting by focusing on the ‘trial run’ which happens the evening before.

The sport of fox hunting has been banned in a number of countries:

Fox hunting is defined as a fieldsport in which hunters follow a pack of trained dogs as they pick up the scent of a fox, chase and kill it. They follow on foot, on horseback, in cars and on motorbikes. It has been banned in many countries, but is still popular in Australia, the United States, Canada, Ireland, France, Italy and elsewhere.

Discover Wildlife, What is fox hunting and why was it banned?

Basically, fox hunting was banned because it is cruel. (The article goes into more details.) Even in countries where fox hunting is banned, it is unfortunately very easy to get around the law.

Why does it continue here in Australia? Partly because foxes are an ecological disaster, which is hardly the foxes’ fault:

The hunt was originally established [in Australia] as a means of pest control. Ironically, the English introduced the red fox to Australian shores to pursue the hunt. It has since caused the extinction of ten indigenous species.

Equestrian Life

I’d also wager there’s a tough-guy, larrikin aspect to certain Australians (typically in men but also, increasingly, in women), wherein you’re soft, latte-sipping city slicker if you care about the feelings (pain) of an animal, especially if that animal causes ecological damage. The same callous attitude applies to cane toads, kangaroos and, on Melbourne Cup day, horses.

In Fox Hunting, What is a Beller?

In Houn’ Dog, we are consistently told that the main character (the hound) is a ‘beller and a smeller’. I had a little difficulty working out the meaning of ‘beller’, at first thinking it a phonetic spelling of ‘bellow’ (meaning to bark). But no. It refers to an actual bell. First I found this article from a century ago:

George Washington, who was a devoted fox-hunter, usually hunting three times a week, had a well-trained pack and a fine stable of horses at Mount Vernon. With his usual attention to detail, he had intimate knowledge of each of his horses, and knew every hound by name and according to his particular merits. Among the hounds were Vulcan, Ringwood, Singer, Truelove, Music, Forester, Rockwood, and Sweet lips. When I reflect upon certain of these names, I begin to suspect that Washington would hardly have shared my sentiments toward the ever-bellowing hound.

Here in Wisconsin we do it differently. We have a method of hunting the fox which employs nothing of this mere conquering force, but moves purely along lines of fox nature and human nature. It is known as belling the fox, and consists in following his trail in the snow and ringing a good-sized dinner-bell. For this work an old man is best adapted, the reason being, not merely that he has had years of experience and is hard for a fox to throw off the trail, but that his weight of years will keep him from getting in a hurry. Youth, becoming wrought up and interested in the chase, unconsciously walks faster and faster. Age and philosophy is willing to save its strength and to keep trudging along. There is plenty of time to catch a fox. This form of the hunt has regard for the Shakespearean adage that what you haven’t got in your head you have got to take out of your heels. Grandpa, who is playing the part of the hound, with the assistance of the dinner-bell, is fully as wise as he looks; and it is an axiom of the chase that haste is not required. He keeps in mind that other old adage — the more haste, the less speed.

Belling a Fox by Charles D. Stewart, The Atlantic Archives, June 1921 Issue

Mary Calhoun’s Houn’ Dog is set in ‘the piney woods of the southern mountains’

In short, the beller refers to someone ringing an actual bell, or hunting horn. This bell is used in fox hunting to signal the beginning of the hunt and to give commands to the hunting party during the chase. The hunting horn is usually played by the master of the hunt, or the person in charge of the hunt. It is also used to signal the end.

In Houn’ Dog, a dog is used in place of a hunting horn. Foxhounds are the traditional breed used in fox hunting, trained to follow the scent of the fox and alert the hunting party to its presence with their distinctive vocalizations. “Ah-roooooo!” Foxhounds locate and track the fox during the hunt, and help drive it the poor animals towards the hunters.

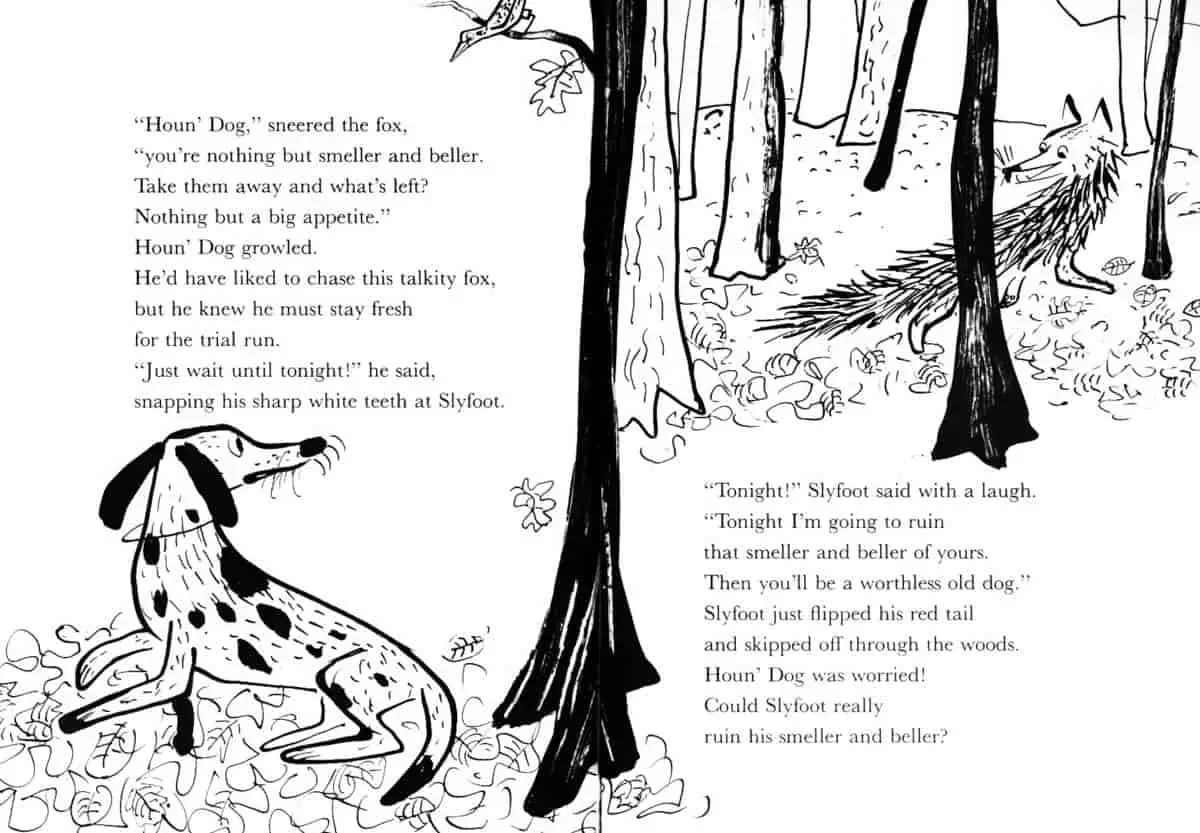

If this were a modern picture book, empathy would lie with the poor, hunted fox. But because this was published in 1959, empathy lies firmly with the foxhound, who is taunted by the sly and evil fox. We know the fox is a Baddie because of the Supervillain moniker ‘Slyfoot’.

Reminder: The fox has threatened to (temporarily) ‘ruin the foxhound’s beller and smeller’, presumably so he can’t be… KILLED.

Note: Young readers presumably don’t cotton on that in a fox ‘race’ the fox will end up dead. And if they do, that’s probably because they’re already familiar with the sport, and have learned to switch off empathy for foxes.

I wondered if, perhaps in America, the fox hunt really is a race, meaning the hounds are trained not to kill the fox. So I looked it up. Apparently it really is a race and not a hunt. So Houn’ Dog is an example of a picture book which sits differently with different people from different parts of the world. I have such a negative association with all types of dogs chasing foxes for sport I can’t fully appreciate this story line.

In America, fox hunting is also called ‘fox chasing,’ as the purpose is not to actually kill the animal but to enjoy the thrill of the chase. A hunt may go without a kill for several years, despite chasing two or more foxes in a single day’s hunting. As a rule, foxes are not pursued once they have ‘gone to ground.’ Contrary to many of forms of hunting, American fox hunters undertake stewardship of the land, and endeavor to maintain fox populations and habitats.

A Brief History of Fox Hunting In America

Surely it’s still traumatising? For the fox to be chased? Do wild animals experience trauma, or are their memories built to avoid that? Anyway, here’s what fox chasing experts believe about foxes: That foxes like to be chased.

Another misconception is that the fox is a terrified and confused creature—somewhat like a deer—frantically trying to escape from the pack of baying hounds. Not so. He is an extremely clever, calculating animal who knows exactly how good or bad the scenting conditions are and who frequently controls the entire chase by various ruses and deceptions. He seemingly enjoys the sport of it, then goes home when finally tired. An ex-Master reports that on one hunting day in 1926, during a four-and-a-half hour period, a fox deliberately led the pack over “every bad scenting spot he could pick out; he walked on rocks for a half mile; he traversed over three miles of stone walls, and in one place walked a rail fence for three hundred yards, retracing his own steps to add to the fun.”

American Heritage

Here’s the thing though: As we learn more and more about animals, knowledge only goes in one direction. Animals feel more pain and (mammals especially) are more similar to us than we previously thought.

As an example which pertains specifically to foxes, it used to be Common Knowledge that foxes kill for pleasure. Evidence? Farmers would find all of their chickens murdered in the coop, yet the fox had only taken one to eat. However, once foxes were properly studied, it became apparent that foxes do not kill for pleasure. They will come back for the rest of their kill, unless they are disturbed, in which case they are smart enough to make themselves scarce.

Likewise, the escape tricks employed by foxes in a fox chase (described above) are likely due to the fox’s intelligence, and we should know better than to think we can read a fox’s mind to the point where we understand their emotions.

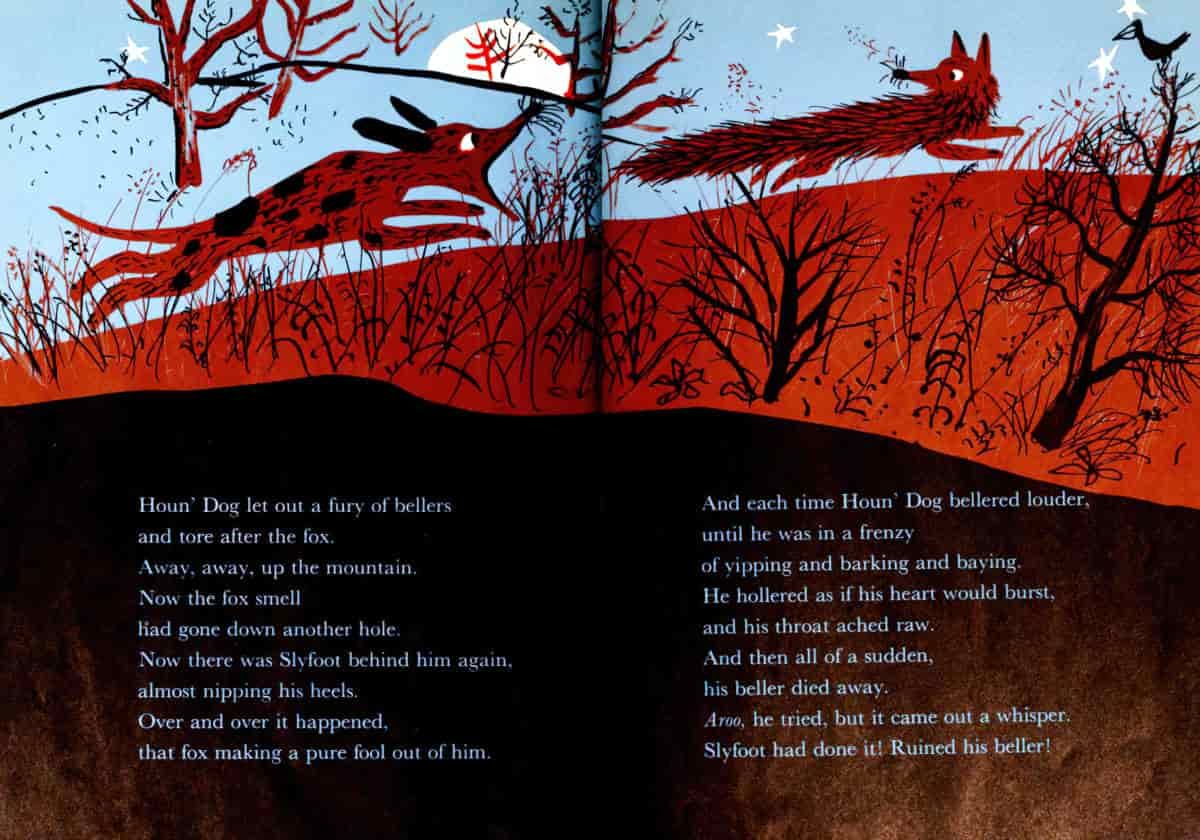

The Chase

The night before the hunt, the foxhound is sent to chase the fox on a trial run.

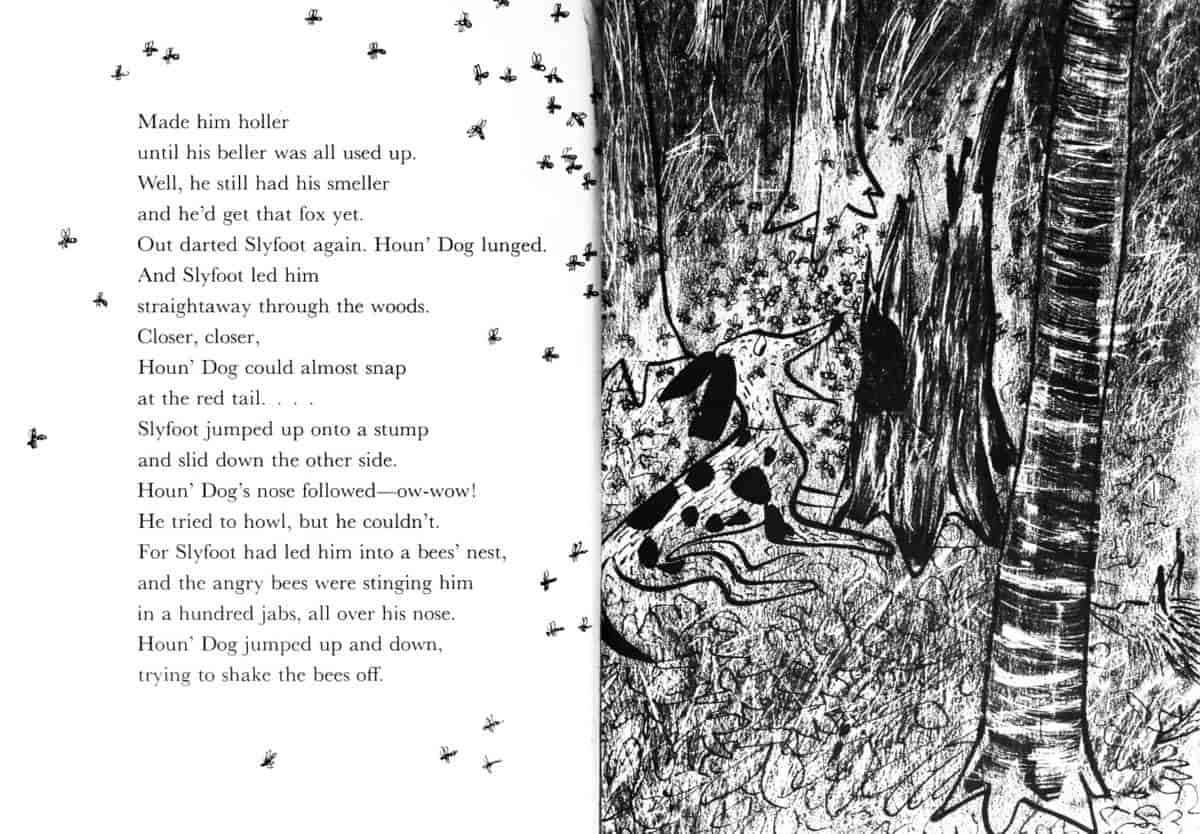

Attacked by Bees

This doesn’t go well.

The bee attack helps readers to side with the foxhound. The fox has outfoxed him, making him bark until he’s lost his voice, and leading him straight into the path of angry bees. Writers use a toolkit of tricks to make sure readers empathise with certain characters and not others. It’s not hard to do, mostly because readers are like ducklings. We fall in love with the first character we see.

At home, he gets TLC from his master, who applies a mud poultice to his snoot.

A Miraculous Recovery for Houn’ Dog

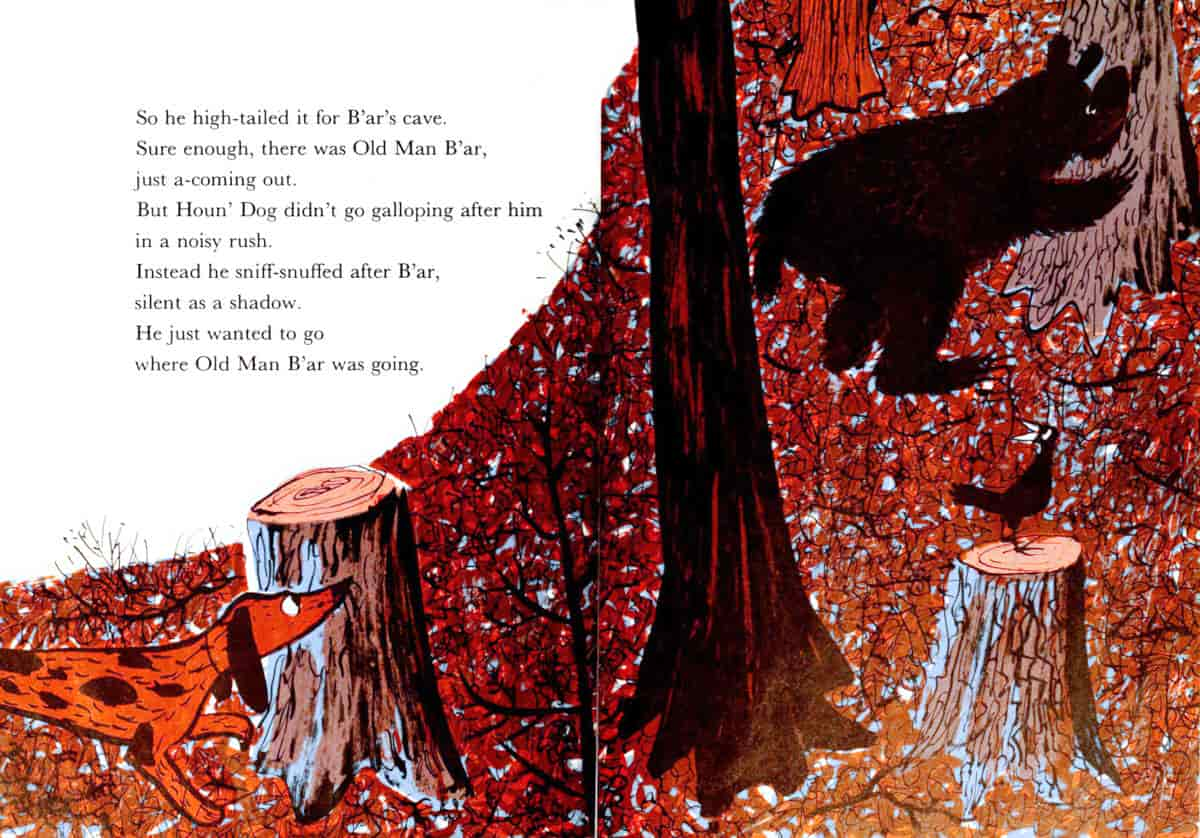

But his throat is still sore from hollering. Industrious problem-solver that he is, he goes to the woods and finds the bear (“Old Man B’ar”), who leads him to soothing honey.

My favourite line of the book: “All the bees were out on honey business.” He shoves his head into the beehive and soothes his throat.

Now his nose and throat (smeller and beller) are both all better and he is fit and able to join in the ‘race’ this evening.

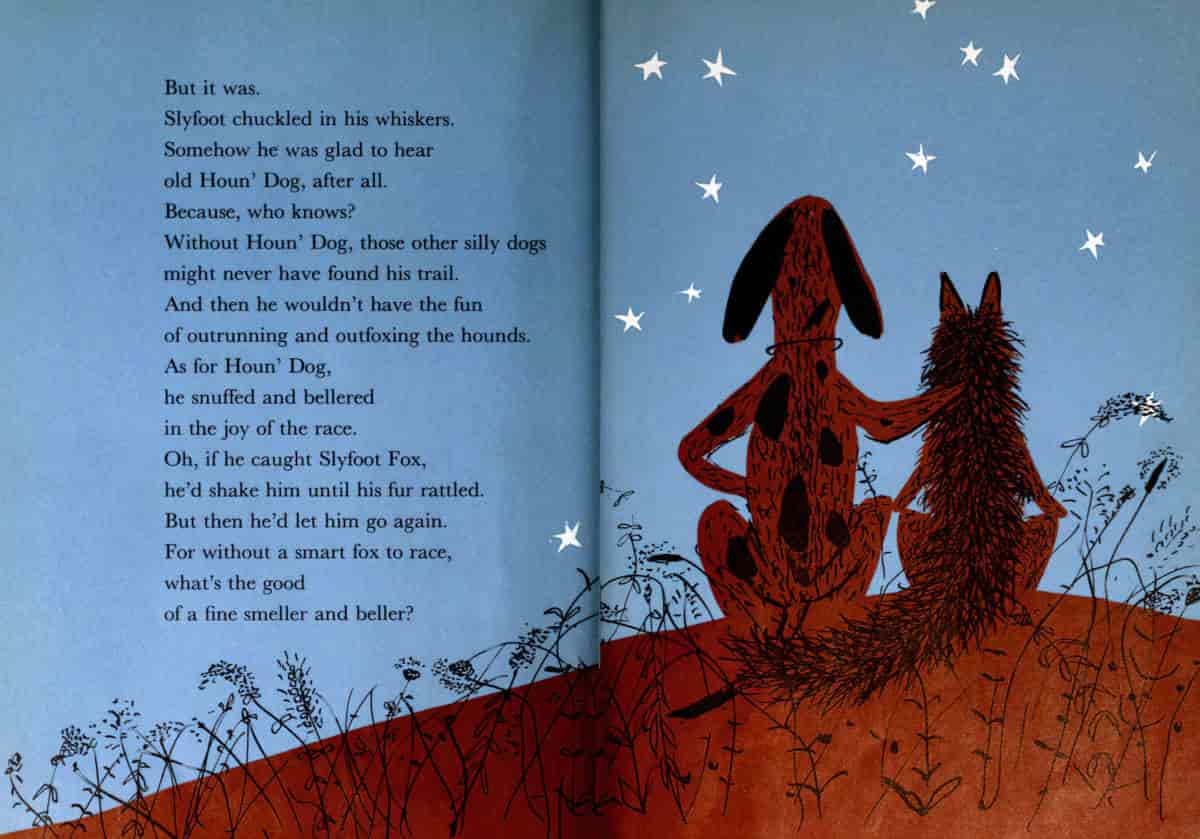

Does this picture book end with the poor fox chased into a fox hole by twelve hounds, limbs ripped off? Strangely, no!

Empathy Switch

Now the story switches to the fox’s point of view, indicating readers are to switch empathy:

Houn’ Dog ends with this schmaltzy scene, in which we’re to believe, apparently, that foxhounds and foxes are friends, actually, and not real enemies at all. Recall we were told earlier in the book that hounds and foxes are closely related, both of the canine species.

Animal Cruelty and Children’s Books

If you go back a little further in the history of children’s literature, the animal cruelty is right there on the page. Take Cider Duck (1969) from Australia which is actually a decade newer but, as evinced by the fact that Australia continues its fox hunting for sport, Australia is in a different cultural spot when it comes to animal cruelty. The Cider Duck is a truly disturbing story by today’s standards, now that we acknowledge birds feel pain. Houn’ Dog slips into that middle zone, where a plot relies upon the cruel practice of fox hunting, but the author attempts to ameliorate the ending by changing the nature of reality on the page.

Unfortunately, this serves as propaganda, since the young reader is left believing that, in a fox hunt, the hounds and the foxes are friends, actually.

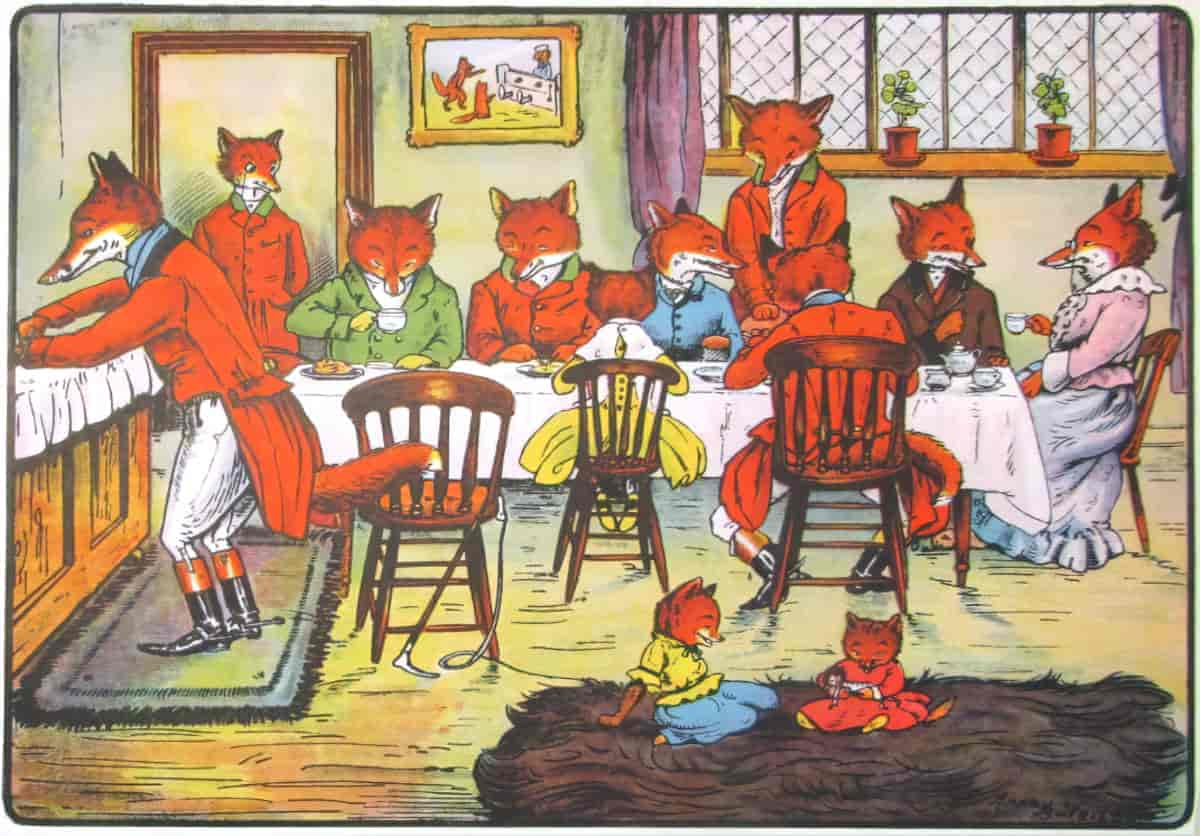

THE FOX’S FROLIC BY HARRY B. NEILSON AND SIR FRANCIS BURNAND

Here’s another picture book featuring a hound and a fox. Just by the cover, we can see the plot and relationship is quite different!