Horses and horse-like supernatural creatures go way back in folklore. They don’t get much of a mention in Grimm’s fairytales, but I’m guessing that’s only because horses were simply assumed. Mentioning horses would be like us pointing out all the cars.

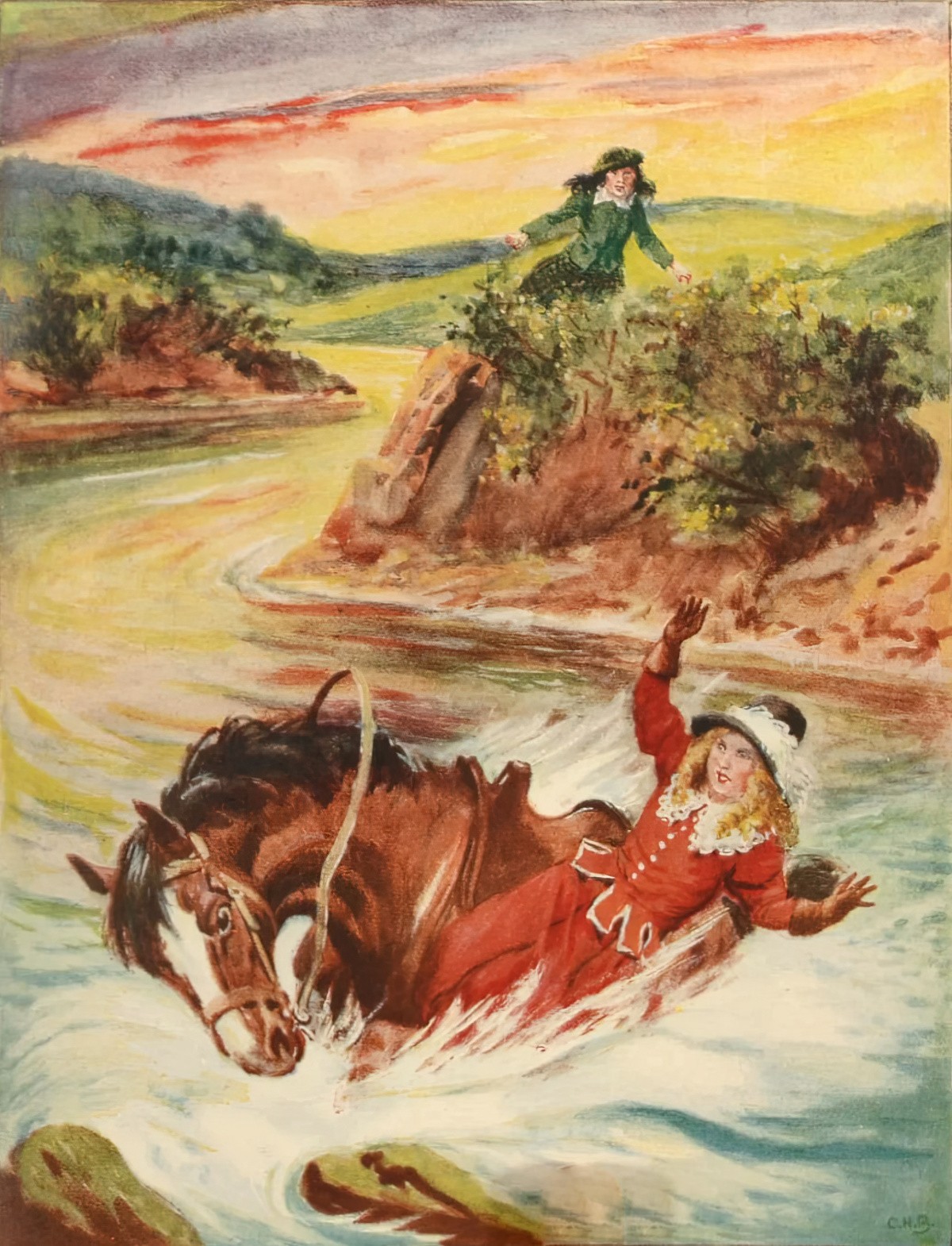

The water-horse or kelpie was a creature from English folklore. This horse was a trickster. It liked to fool humans into thinking it was just an ordinary old horse. But if you forgot to check it for sand and seaweed in its mane, more fool you! The water-horse would whisk you off to the sea and drag you beneath the waves. You wouldn’t come back.

Today, horse stories are marketed at and mostly read by middle grade girls. That was not always the case. Before the motor car, horse books were aimed at boys. In England, horse books are known as pony books. In Australia, too, our local kids join ‘pony club’. I recently asked one of the girls why it’s called pony when they ride horses. She didn’t know.

What about actual horses, when horse stories started to be written down?

A Brief History Of Horse Books

The Book That Influenced Black Beauty

The Adventures of a Donkey was published in 1815.

When you know about this book you realise Black Beauty isn’t as original as it at first appears to be.

Margaret Blount lists the main similarities between The Adventures Of A Donkey and Black Beauty in Animal Land:

- The animals are not held up as moral examples, but there are ‘good’ and ‘bad’ ones as there are good and bad humans, lack of speech being the only animal disadvantage

- The donkeys talk to each other and understand human speech

- Jemmy’s mother advises him to be docile and obedient, as Black Beauty’s Jemmy is also advised by an older donkey (Balaam) the Merrylegs of the story and he relates with some feeling what it feels like to be shod, with its strange noises, heaviness and height.

- There’s considerable detail about riding, driving, saddling and being hired on donkey races and the use of blinkers, on the traffic of the day in Fleet Street, Chancery Lane, Holborn and Russell Square, where at the side of the road donkeys drawing carts could be almost knee deep in mud.

- Jemmy, in a similar manner to Black Beauty, ends up broken-kneed and is bought at last by a kindly lady.

Anna Sewell herself was hugely influenced by her own mother, Mary Sewell. Anna was permanently lame and often ill and overshadowed by the active Mary. She bore a troubled life with great courage and patience (err, just like Black Beauty).

The Influence of Black Beauty On Everything Else

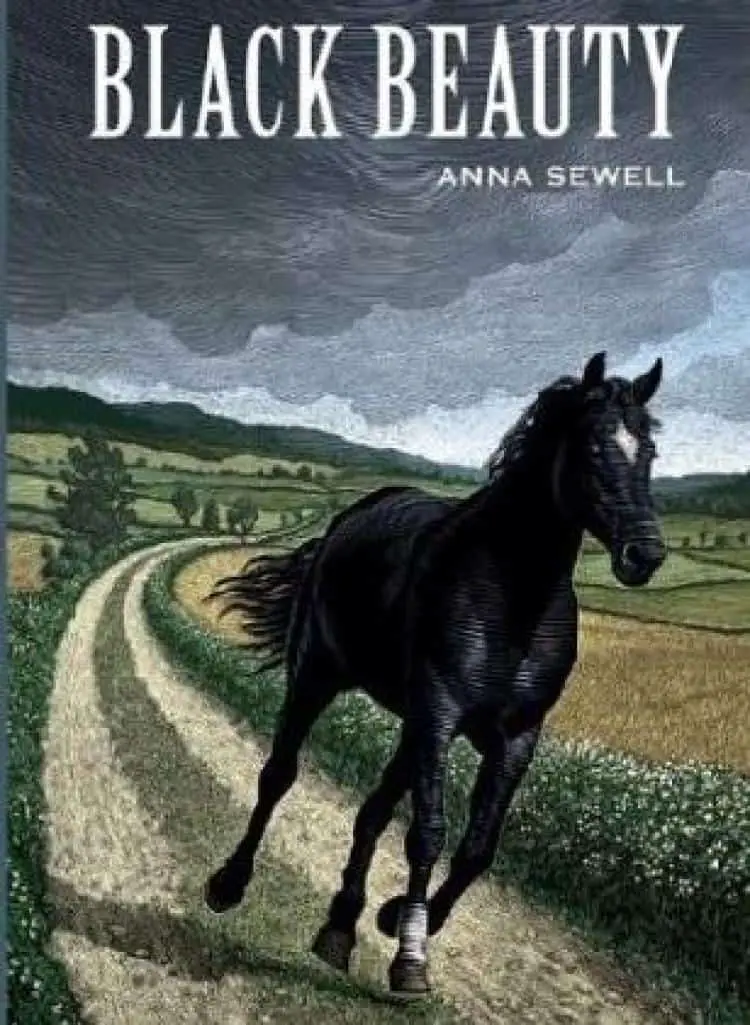

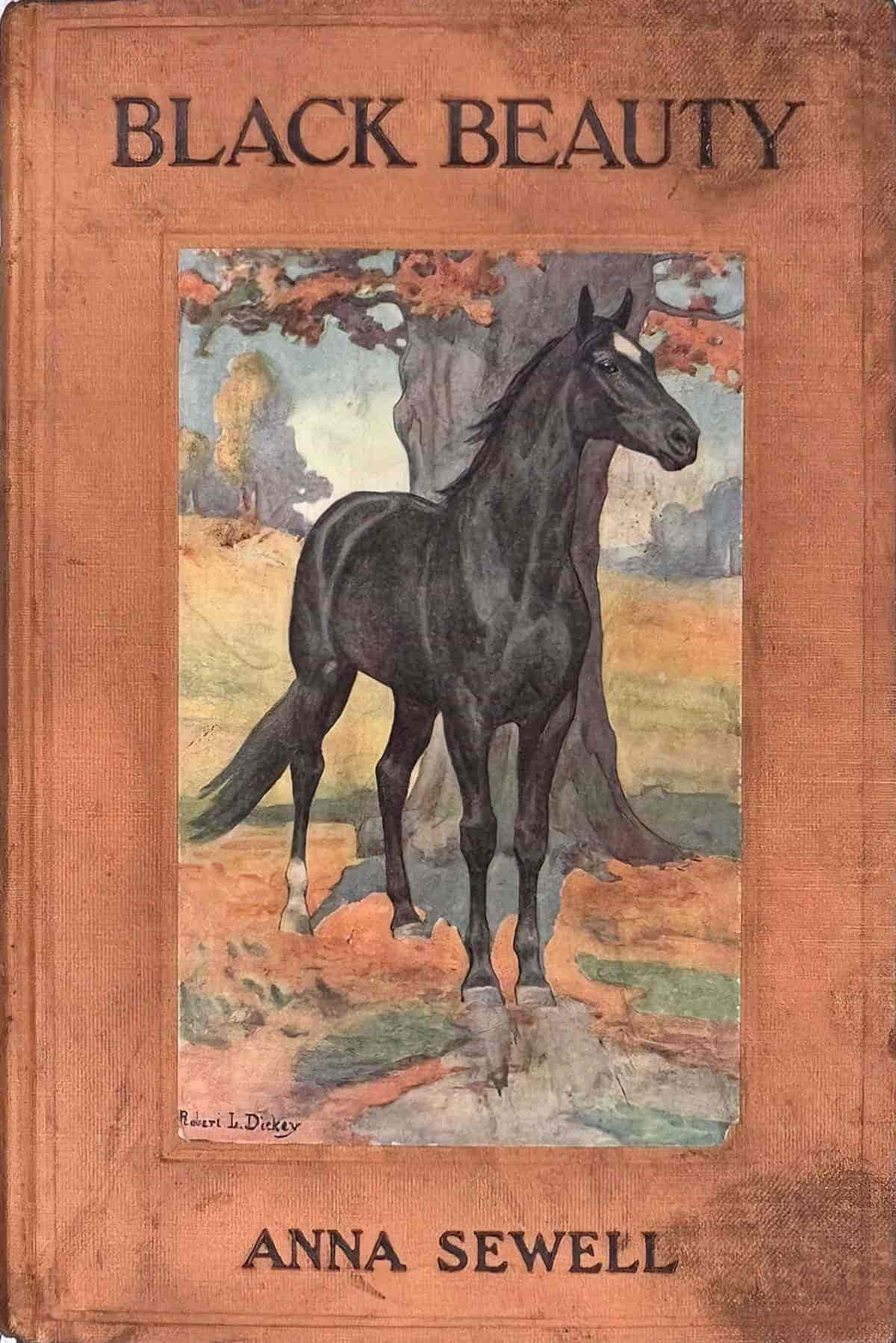

Black Beauty was the first animal story of major importance, published 1877. It was Anna Sewell’s only book. She wrote it in the last years of her life ‘to induce kindness, sympathy, and an understanding treatment of horses’. The story is written from the horse’s first ‘person’ point of view. In fact, Black Beauty was the last of the great first person narratives in the Listen-to-my-life series.

Black Beauty is culturally significant because it the last of the ‘moral books’. Though heavily moralistic on the care of horses, and even though it became outdated once the motor vehicle became a mode of transport, Sewell was forward-thinking in her condemnation of fox-hunting and war.

Even if I personally never wish to be sent another book about a little lost kitten, Black Beauty laid the foundation for the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Amanda Craig

If Uncle Tom’s Cabin changed the way white people began to see black people, novels such as Black Beauty changed how we see animals.

Amanda Craig

Black Beauty had a heavy influence on the following:

Beautiful Joe, published 1893, was a very popular imitation of Black Beauty, though about a dog, written by Margaret Marshall Saunders. But it now looks like a bad caricature of the worst parts of the original.

Then there’s Smoky by Will James (1926) about a cow-horse told by a cowboy. The setting is different but it’s also about animal cruelty.

C.W. Anderson

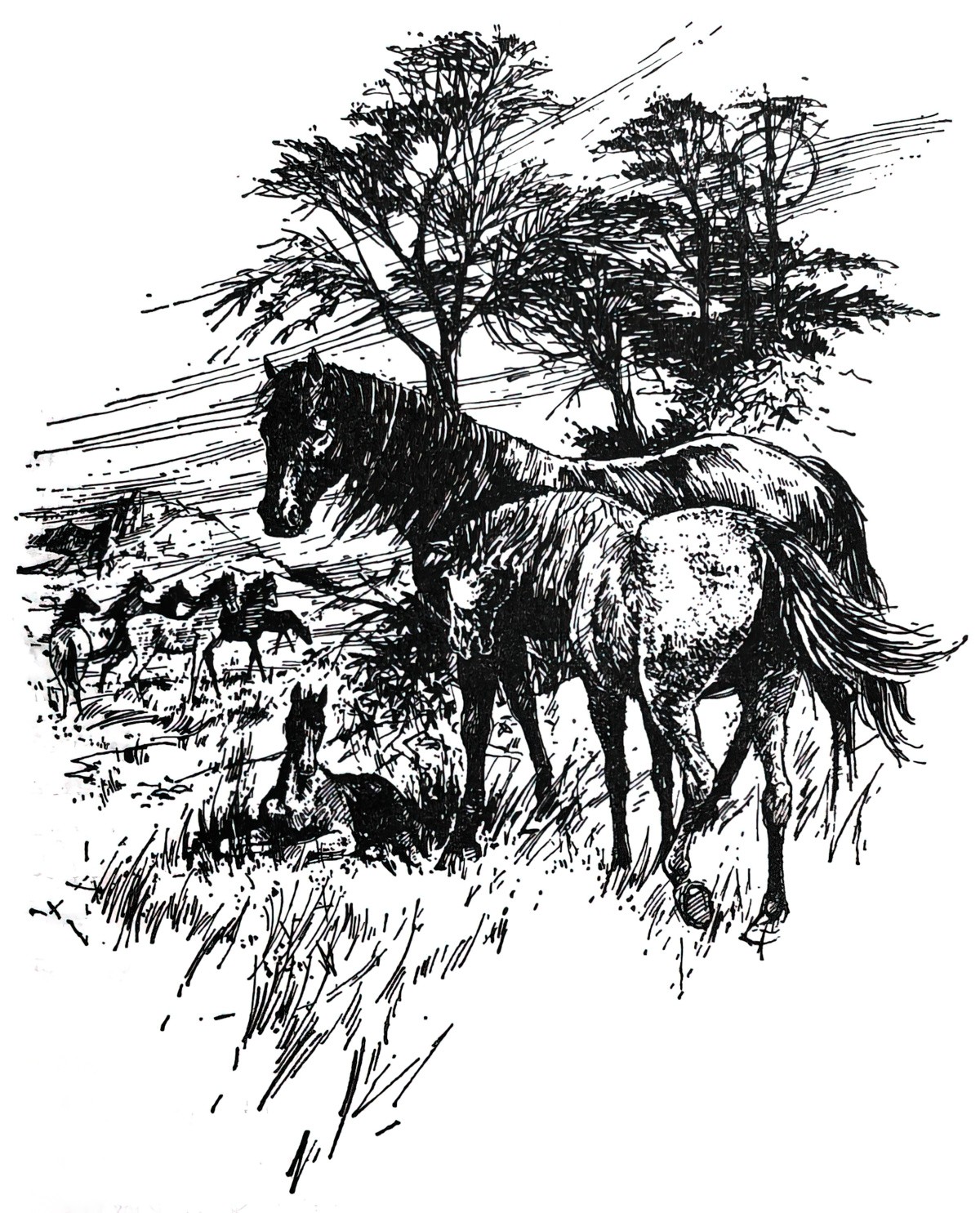

Published from the 1930s to 70s, nearly all of C.W. Anderson’s fiction—which includes the eternally compelling Blind Connemara—involve a rider taking a heretofore overlooked horse, retraining it, and going on to win—the cup, the steeplechase, the flat race, the big show. Anderson was a first-rate illustrator whose picture book, The Lonesome Little Coltdepicts mares and foals so beautiful and shiny they hurt your eyes.

Caitlin Macy, Lit Hub

Ruby Ferguson

I would pit Ruby Ferguson who wrote the Jill series in the 1950s—Jill’s Gymkhana, Jill Has Two Ponies, A Stable for Jill—against any children’s chapter-book author of the last 75 years. I particularly loved Jill Crewe because she, like me, was not from a horsy nuclear family and could barely afford riding.

Caitlin Macy, Lit Hub

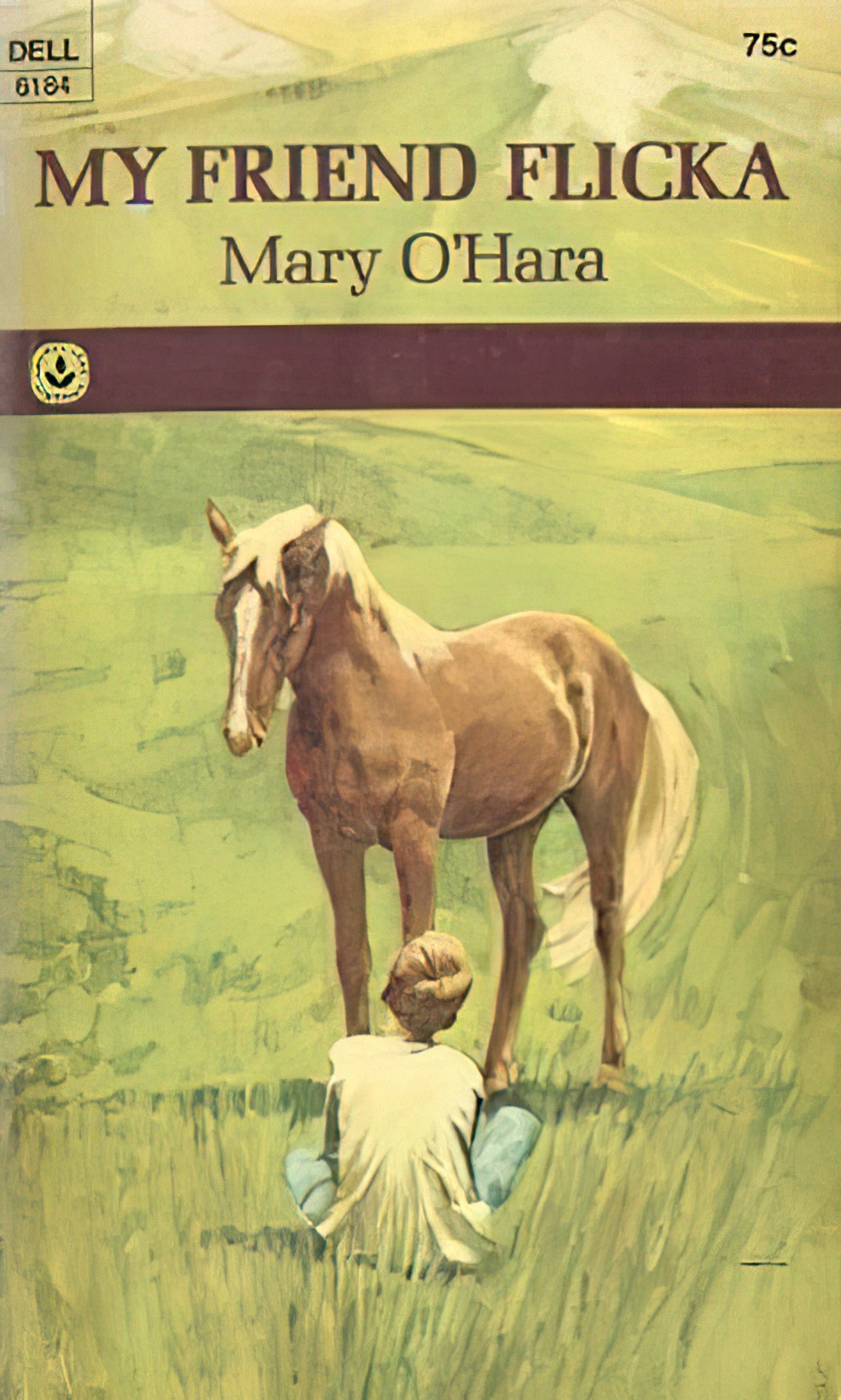

My Friend Flicka

My Friend Flicka (1941) by Mary O’Hara was published as an adult novel but found a child audience. It’s about a boy’s struggles to break in a half-wild filly. Its subplot is a father-son conflict. But since Flicka was first published it has been decided somewhere along the line that horse stories are for girls. The film adaptations of this century star girls instead of boys. The subplots are either daughter-father or daughter-mother conflicts.

Horse books peaked around 1950, a few decades before the young adult category became a thing. Horse books are basically proto YA.

Horse Stories: Just for girls?

When it comes to the target audience of horse stories, there seems to be a transitional period around 1940. As well as My Friend Flicka, The Black Stallion was first published in 1941. Another influential horse story, Enid Bagnold’s National Velvet, was published in 1935 and involves a boy and a girl working together. This model seems to have lasted for some time until the more modern “pony club” genre for girls emerged.

The Gender Of The Actual Horses

Horses and Headlocks from The F Word blog, by a non-binary author looking into why even horses are gendered.

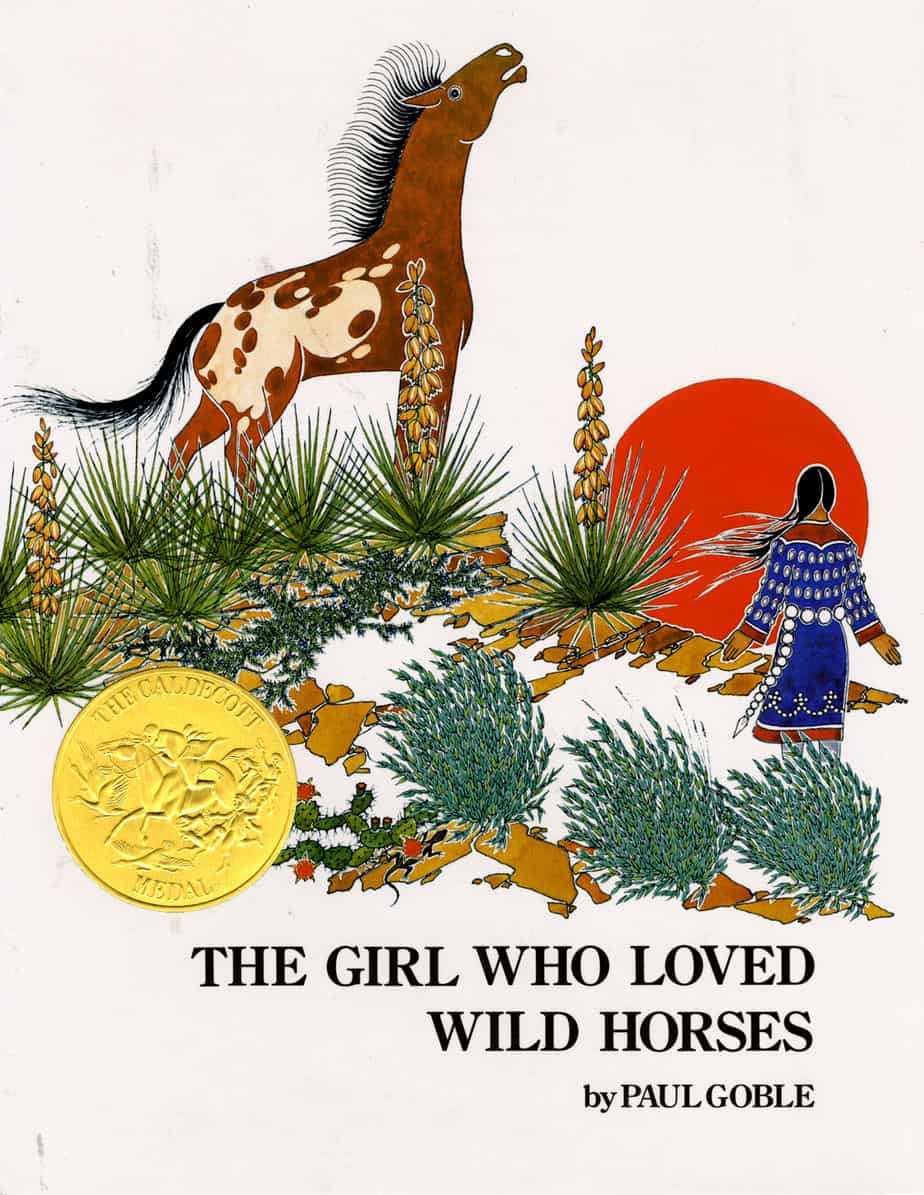

Along those same lines: Why are there so few female horses in speculative fiction?

Horse Stories And Genre

Horse stories are not a genre. Horse stories describe stories from any genre in which horses feature prominently.

You might think that the range of horse books would be narrow, but, like an artist working only in black, reading only one genre—or not really genre but fictive subject—reveals just how many iterations there can be of a thing. If there is, by necessity, some overlap in plot, horse books otherwise offer a surprising breadth: of style, setting, and tone. There are the ones that make you cry—BlackBeauty, Blitz, the Story of a Horse, the more obscure I Rode A Winner—and the ones that get even darker: The Monday Horses by Jean Slaughter Doty, about the ugly truths behind the show ring’s sheen; and one of the later Black Stallion books by Walter Farley in which Henry, the trainer, almost beats a horse to death. There are the westerns, such as the My Friend Flicka trilogy with their tough, working-ranch lessons, which I never cared for quite as much as the “suburbans”—Suzanne Wilding’s Dream Pony For Robin, say—with their more modest insights into how not to be a laughingstock at Pony Club.

Caitlin Macy, Lit Hub

Macy also mentions that authors who normally write other types of stories often produced a one-off horse story, too. A good example of that is The Horsemasters by Don Sanford (1957, proto YA)

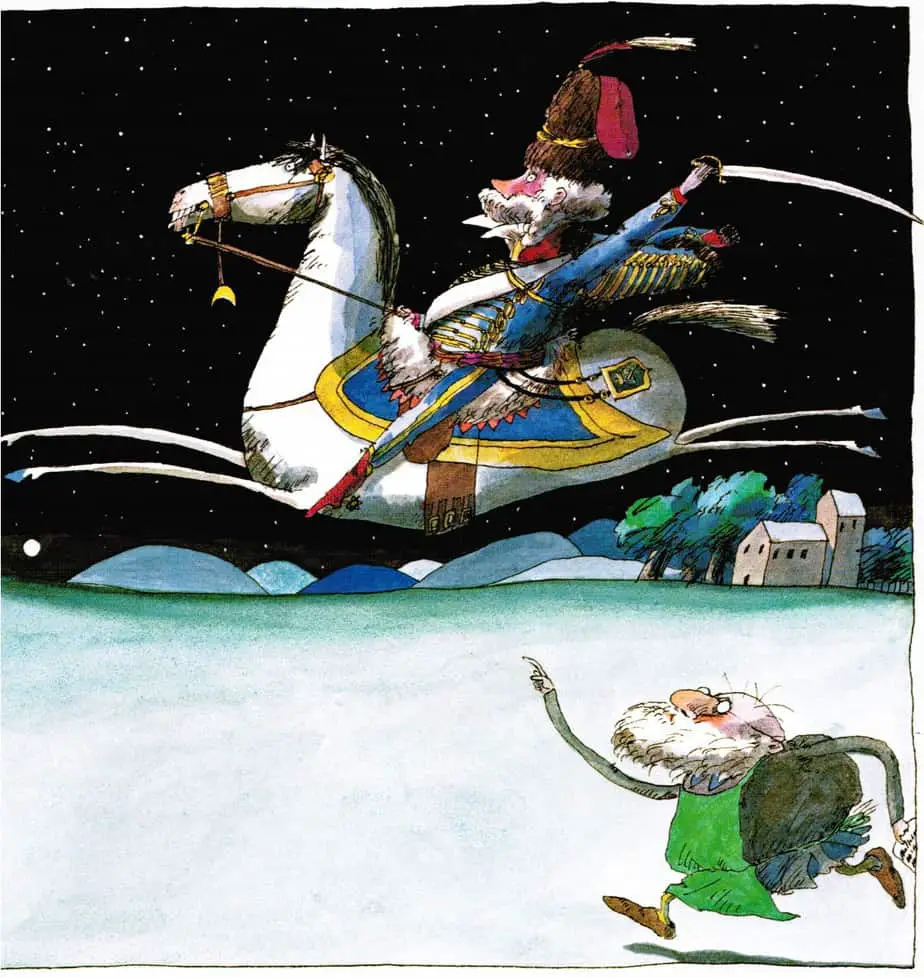

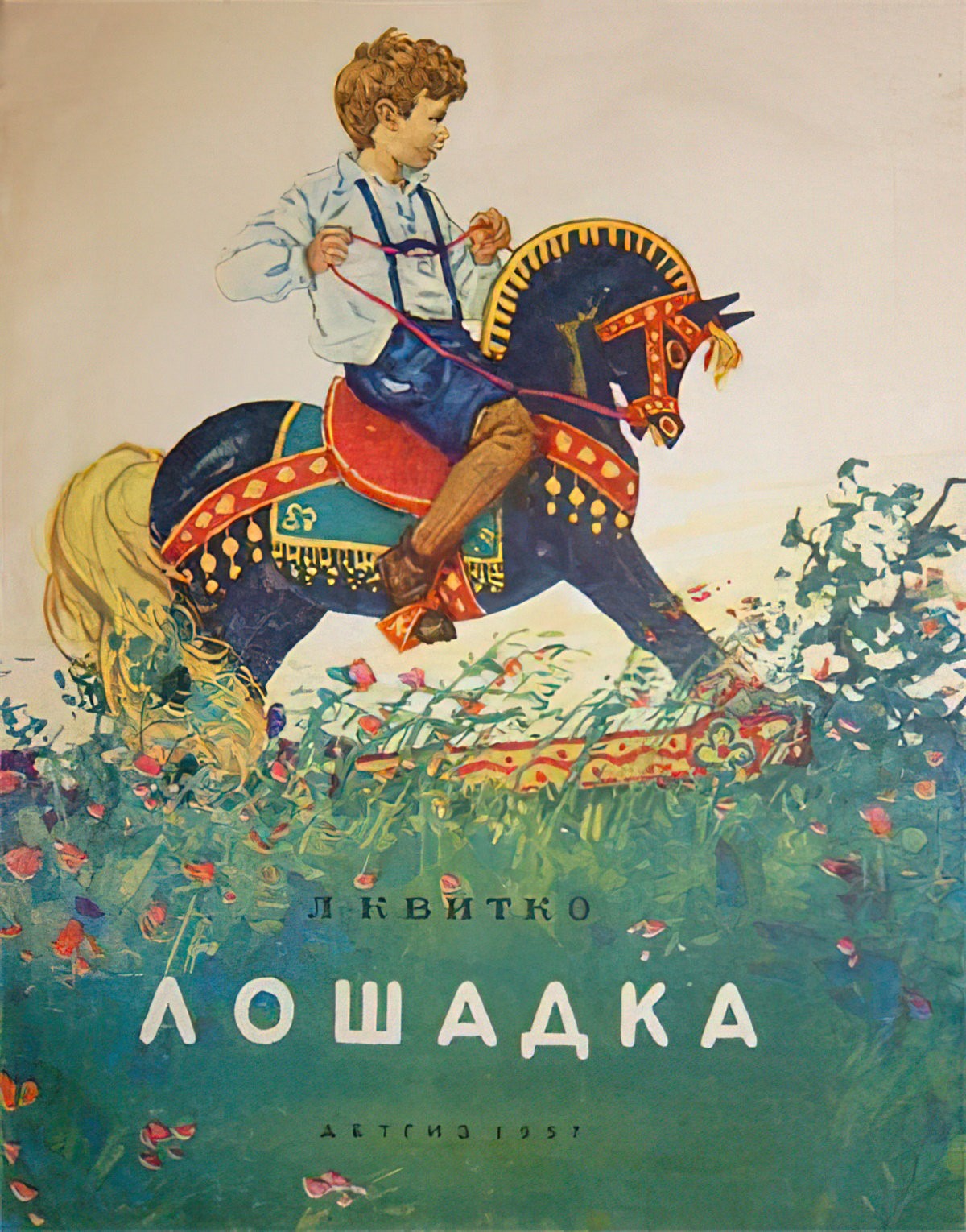

Rocking Horses

Horse books aren’t always about live horses. Here, a Russian picture book seems to be about a rocking horse that comes to life.

Depending on the story, you could code rocking horses as either toys or animals.

MY LITTLE PONY

- My Little Ponies Turned Into Horrible Mutant People from io9

- All Girls Like Ponies, explained at TV Tropes

- Bronies from Beautiful Decay

- Brony spectacle signals acceptance of ‘different kinds’ of masculinity from The Age