Supernatural stories about ghostly hitch-hikers are popular fodder for urban legend. How do you take a classic and turn it into something new? Shirley Jackson demonstrates how in a short story from the Dark Tales collection: “Home”.

Knowing too much about other people puts you in their power, they have a claim on you, you are forced to understand their reasons for doing things and then you are weakened.

Margaret Atwood

WHAT HAPPENS IN “HOME”

Ethel and her writer husband move out to the country. She sets about forging social connections in the main street shops. But Ethel fails to heed local warnings about making use of an old country road. A few days into her new life, meets a couple of ghosts standing in the pouring rain. She insists on giving them a ride and is then horrified to learn they would like a ride to her house, please. They disappear and she is delighted to now have a ghost story. This makes her a true local.

Unfortunately for Ethel, the story doesn’t end there. The ghosts reappear next time she hops in the car. The ghosts don’t seem to realise that Ethel now inhabits the house they’d like to haunt.

As the story ends, the other shoe never drops. We are left wondering: What will the ghosts do to Ethel once they realise she’s the new inhabitant of their beloved Sanderson?

GOSSIPING IN SHIRLEY JACKSON’S DARK TALES

If you’re familiar with “The Lottery”, you’ll already know Shirley Jackson’s clear-eyed view on how women’s words are treated compared to the word of men. The unseen narrator of “The Lottery” tells us that the men speak of important farming issues whereas the women ‘gossip’. In this community, the word ‘gossip’ is used to dismiss women’s speech.

“One reason women have traditionally gossiped more than men is because gossip has been a social interaction wherein women have felt comfortable stating what they really think and feel. Often, rather than asserting what they think at the appropriate moment, women say what they think will please the listener. Later, they gossip, stating at that moment their true thoughts. This division between a false self invented to please others and a more authentic self need not exist when we cultivate positive self-esteem.”

bell hooks | All About Love: New Visions (via sinidentidades)

“Home” centres on the wife, who is a gossiping housewife archetype. I need to emphasise this: At no point does Ethel actually gossip about other people, let alone maliciously, but I still read her as this archetype. We do see her become a busybody when she basically manhandles two ghosts into her car. (I find this hilarious.)

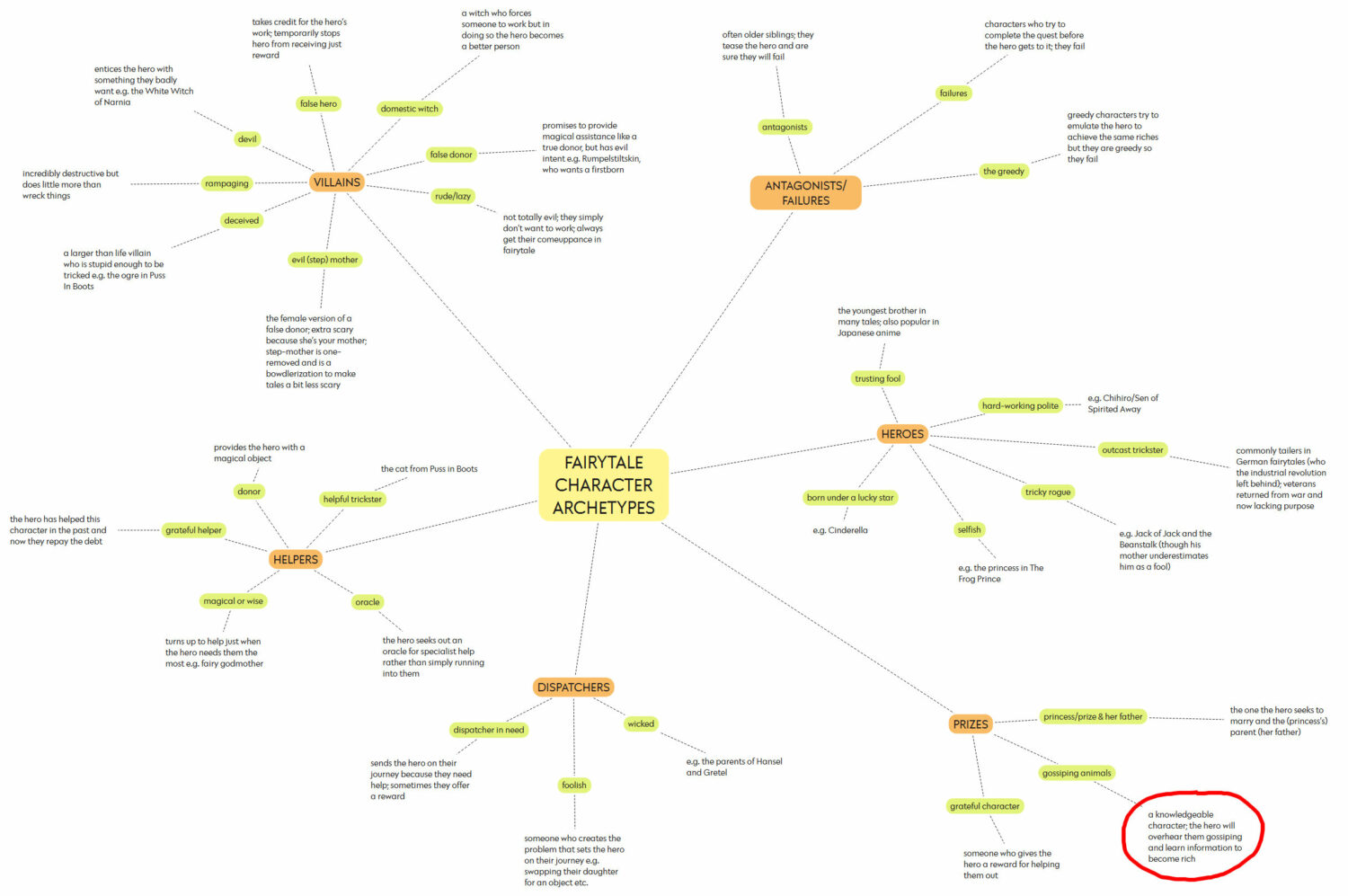

Such characters come partly from the fairytale archetype known as the ‘prize’. Long ago these characters appeared as animals in fables. The ‘gossiping animal’ archetype is a knowledgeable character. Generally, the main character in a story will overhear them gossiping and use this knowledge to become rich.

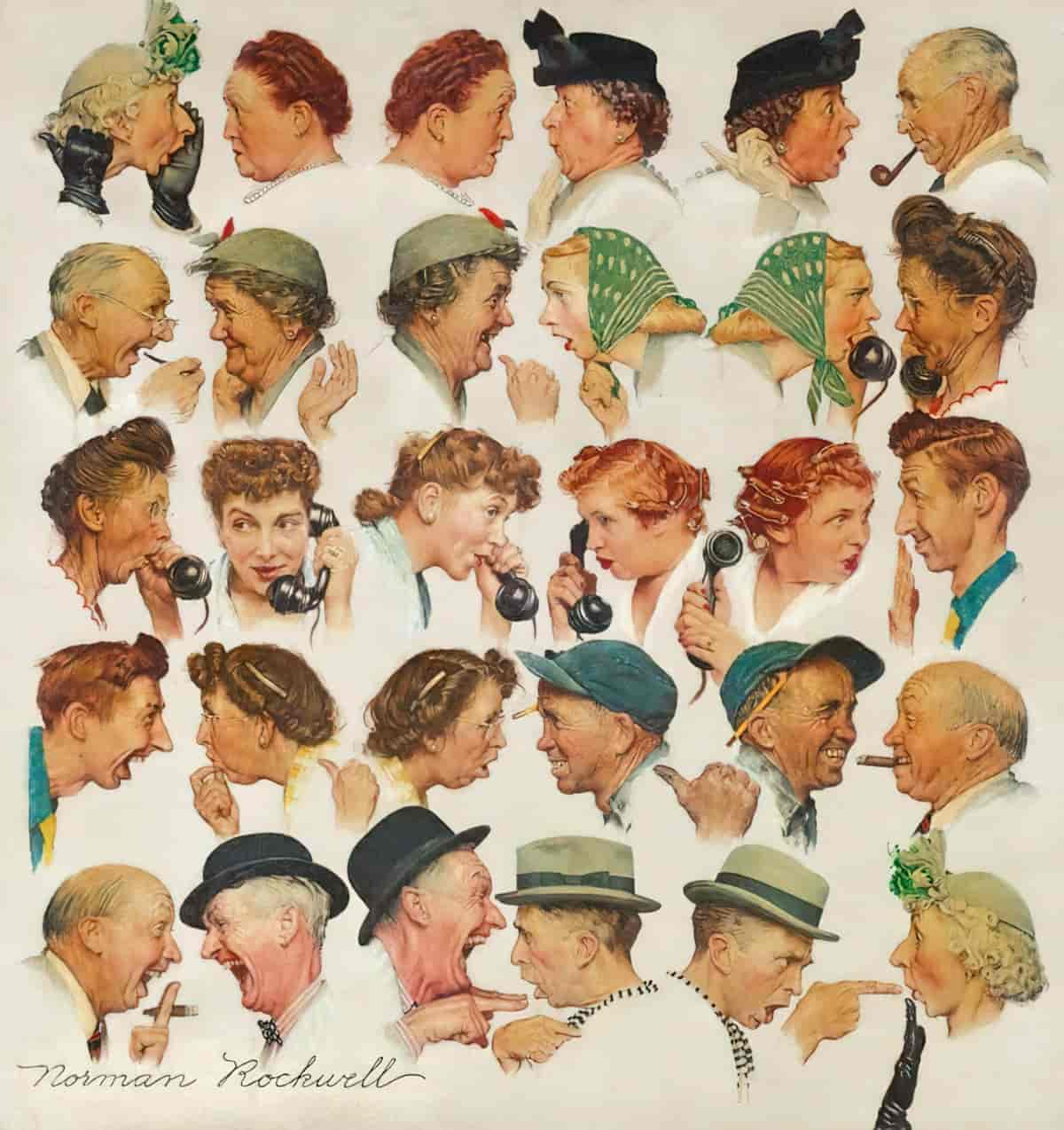

More contemporary stories find various uses for the gossiper. These characters are almost entirely women and girls e.g. Violet from 1980s Australian TV drama The Flying Doctors, Miss Patty or Babette Dell from Gilmore girls or Rachel Lynde from Anne of Green Gables. TV Tropes call these women Gossipy Hens. The women with kind intent are a subcategory of Jerks With A Heart of Gold. When men do it, they’re frequently encoded (and decoded) as gay e.g. the Chatty Hairdresser. Very occasionally you’ll find a Gossipy Rooster, e.g. Sir John in Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility. Sir William Lucas in Pride and Prejudice also gets up in the young women’s business, in contrast to Mr Bennet, who is interested in no one, including the welfare of his very own daughters.

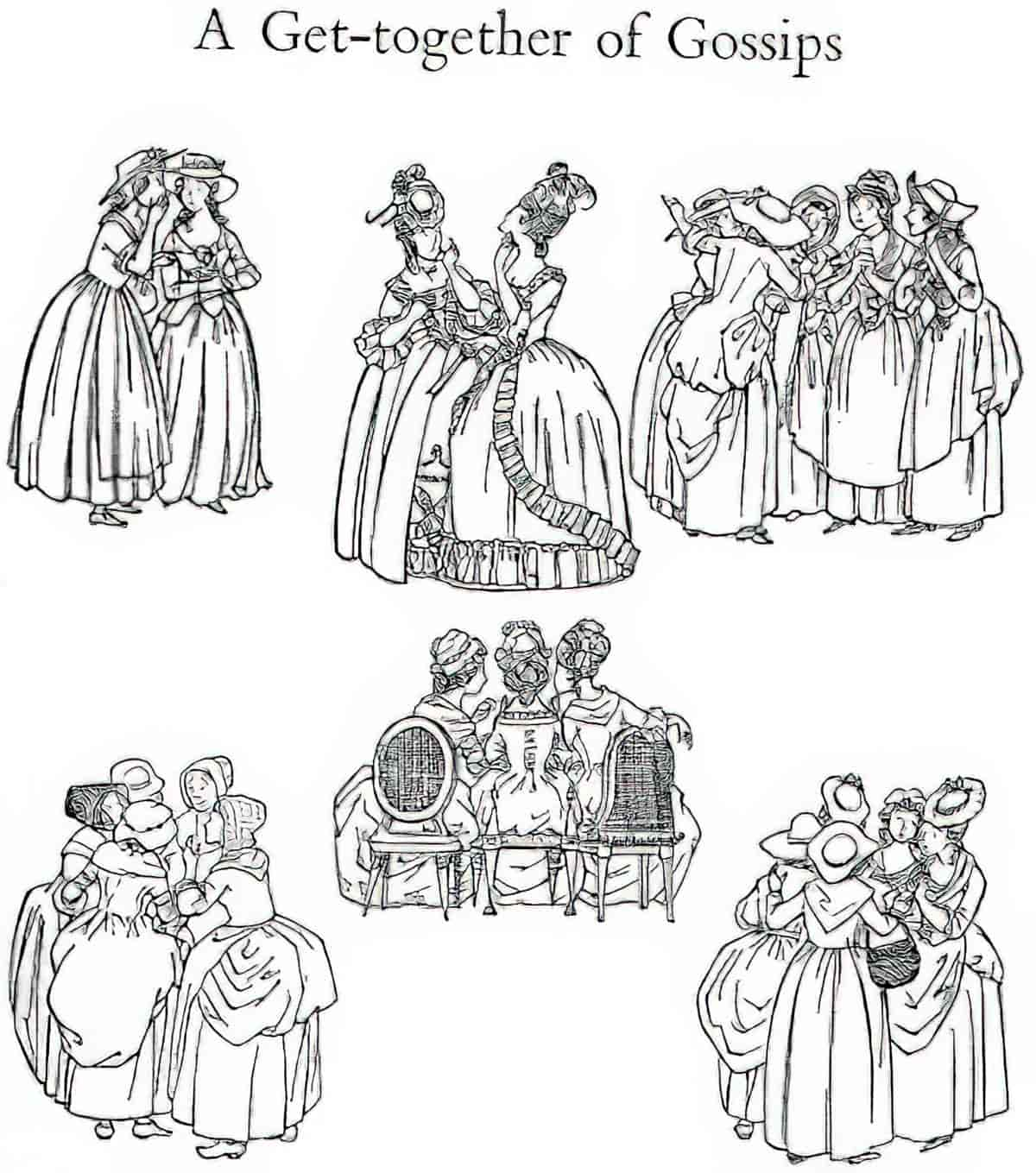

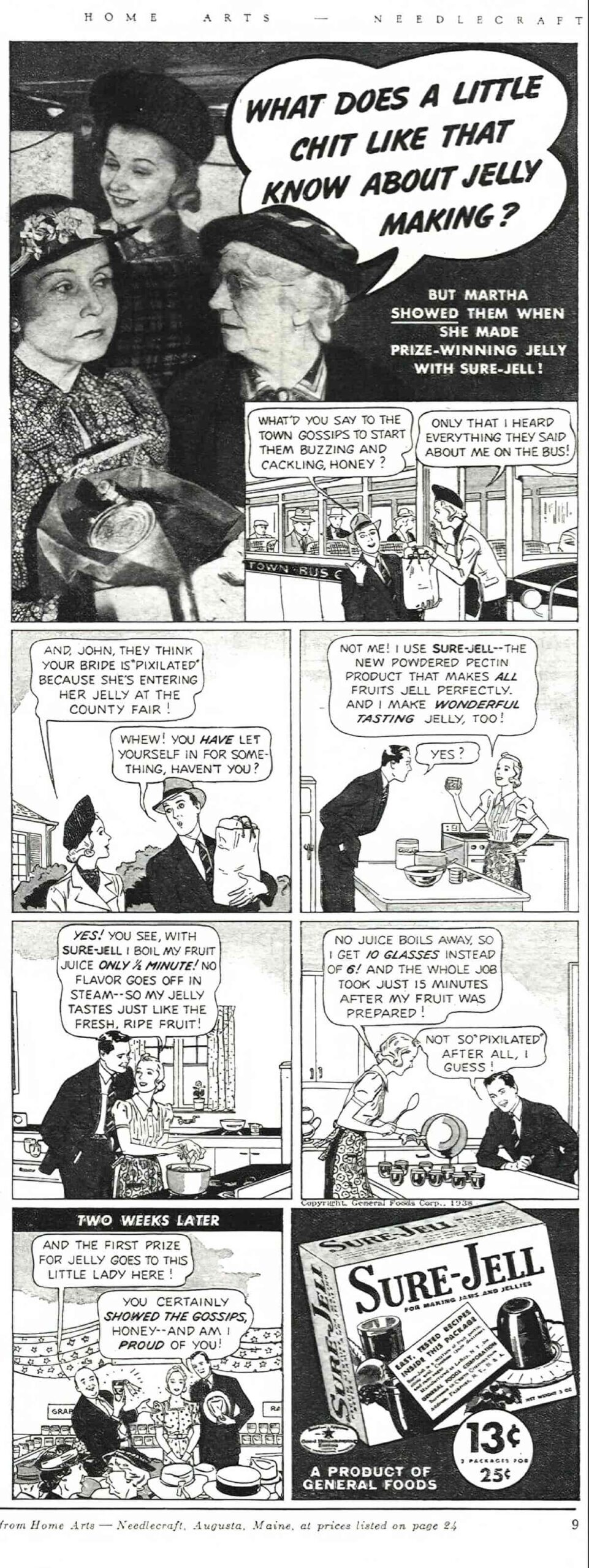

In art and advertising, gossiping women proliferate across the ages:

THE STORYTELLING REASONS FOR BUSY-BODY GOSSIPERS

The gossiping character archetype is very useful to storytellers:

- She lets audiences and characters in on secrets they wouldn’t otherwise know

- She is part of the social setting, explaining to the audience what is and is not permissible by the morality of the time and place

- Her gossiping will be seen as immoral by the audience, and so long as the hero doesn’t also gossip, the hero will look much better by comparison

But the well-meaning gossip is rarely the star of a story. Shirley Jackson utilises the interfering neighbourhood gossip in a number of ways across her stories. In “The Possibility of Evil” (included in the same Dark Tales collection), Miss Strangeworth is an evil, busy-body and self-appointed vigilante citizen, predicting evil before it happens, causing actual mischief in a particularly nasty take on the gossiping trope. (She doesn’t actually gossip; she creates evil quietly.)

GOSSIPING AND THE GENDER HIERARCHY

In the wrong hands, the gossiping character archetype both relies upon and contributes to the pervasive misogynistic idea that women talk maliciously about others, creating trouble where none existed before. Linguists, anthropologists, sociologists and historians have studied the social functions of gossiping so we know for sure that women do not gossip more than men.

THE REAL LIFE SOCIAL FUNCTIONS OF GOSSIPING

- to circulate personal information, enabling members of a community to keep t rack of others’ activities and relationships

- bonding (establishing who is the in-group and who is the out-group) — secrets and personal information works best for this

- affirming a group’s commitment to particular norms and values

Thoughtful writers will acknowledge that such people exist, and here, Shirley Jackson creates a comedic figure but also gives her humanity. She’s the star of her own story. We know this because Ethel Sloane undergoes the character arc.

But if everyone gossips, why has gossip been decried for centuries as a specifically female vice? The historical record is full of injunctions to women to avoid gossip, which was variously denounced as idle, frivolous, anti-social, sinful and even a cover for witchcraft.

Some historians argue that what really worried men wasn’t so much the sharing of arcane female knowledge as the prospect of women talking about them. They feared their wives would share embarrassing secrets, or spread malicious gossip deliberately to damage their reputations. This fear was not unfounded: at a time when women had very limited access to more public forums, gossip provided an alternative channel for influencing the opinions of others. And in a culture that practised quite extensive sex-segregation, it was one channel men couldn’t control.

Deborah Cameron, language: a feminist guide

Dr Cameron also points out, elaborating in a subsequent post, that masculine ‘banter’ is gossip by another name: ‘a ritualised social practice which contributes to the maintenance of structural sexual inequality’.

GOSSIPING BUSYBODIES AS PROSOCIAL AND ANTISOCIAL

Like any attribute, there will be a negative, overstepping flipside when taken to extreme. Every young mother has a story about being chastised by a middle-aged woman in public. These women overstep the bounds, and fail to mind their own business in a public space. Men are far less likely to tell women how to bring up their own children because, due to enforced cultural ignorance, men are not expected to know much about caring for babies and toddlers. To offer opinions on childcare would serve to undermine their own masculine identity. However, all young women have the experience of street harassment, or being told to smile in the workplace. This is the masculinised version; a tool of social control directed at those who have the power to shape the following generation by giving birth and raising them. Shirley Jackson explores the overstepping flipside of caregiving (caretaking) in “Home”.

WHAT DOES ETHEL WANT IN SHIRLEY JACKSON’S “HOME”?

Ethel Sloane is desperate to become part of her brand new community. We can extrapolate that a person like Ethel would have been central to her former village lift; she would have known everyone’s uncle’s monkey’s business as self-appointed village mother.

In this story, Ethel’s motherly instinct is precisely what kicks in when she sees an elderly woman with a young boy standing poorly clothed and cold in the driving rain. Women like Ethel are enculturated their entire lives to be carers. In this case, the word ‘caretaker’ is more appropriate than ‘caregiver’. She forces the woman and boy into her car to assuage her own guilt around leaving them there. The welfare of this pair come very much secondary, evinced later when she learns the horrible backstory of the live people and finds it wickedly entertaining.

THE GHOSTLY HITCH-HIKER URBAN LEGEND

Shirley Jackson wrote “Home” in the middle of the 20th century, when cars frequently broke down and picking up strangers on the side of the road was a strongly prosocial and expected thing to do. (The concept of serial killer did not yet exist in the cultural imagination.) Hitch-hikers were likely to be people just like you.

The road trip story is at least 3000 years old (we call it the Odyssean myth) but didn’t become a ‘road trip story’ until America’s main highways were built. This led naturally to urban legends about travellers who dared deviate from the highways. Ironically in these stories, if you don’t step off the expected route (the highways) you’ll live an unpleasant, overly-structured life as an automaton, but if you explore the old trails, sure you’ll almost die, but you’ll also learn some valuable information about life as it really plays out.

When Ethel moves from the city (or from nascently developing American suburbs) to a small rural town, she’s risking her own well-being. But she’s also becoming a better person in the process — more humble. The busybody side of her pro-socially outgoing nature is reined in after a supernatural experience with a ghost. We can expect with this new humility she will fit in nicely, so long as she finds a way to make herself useful as a community member.

DID ETHEL ‘REALLY’ SEE GHOSTS?

As always, we can read this ghost story as a metaphor for a character’s state of mind. In this reading, Ethel moves to the country, ignores local advice to avoid a particularly dangerous road, then almost has a car accident as she drives in the rain regardless. After that, she has learned her lesson. She will no longer trust her own city slicker instincts, but instead understands that some hazards are peculiar to rural areas, and she needs to pull her head in or she’ll become a ghost herself. She sees these ‘ghosts’ every time she gets into her car, as a reminder to be careful on the road.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

The short stories of Annie Proulx are tonally very different from those by Shirley Jackson, even though both women wrote their stand-out short stories in middle-age after raising large families. Both authors make use of supernatural tropes alongside realistic settings to explore the anxieties around motherhood.

Compare Shirley Jackson’s “Home” to Annie Proulx’s Wyoming stories. Both writers have something to say about city slickers who move out to the country expecting to enjoy rural American life, only to find a far more harsh and unforgiving landscape than they expected.