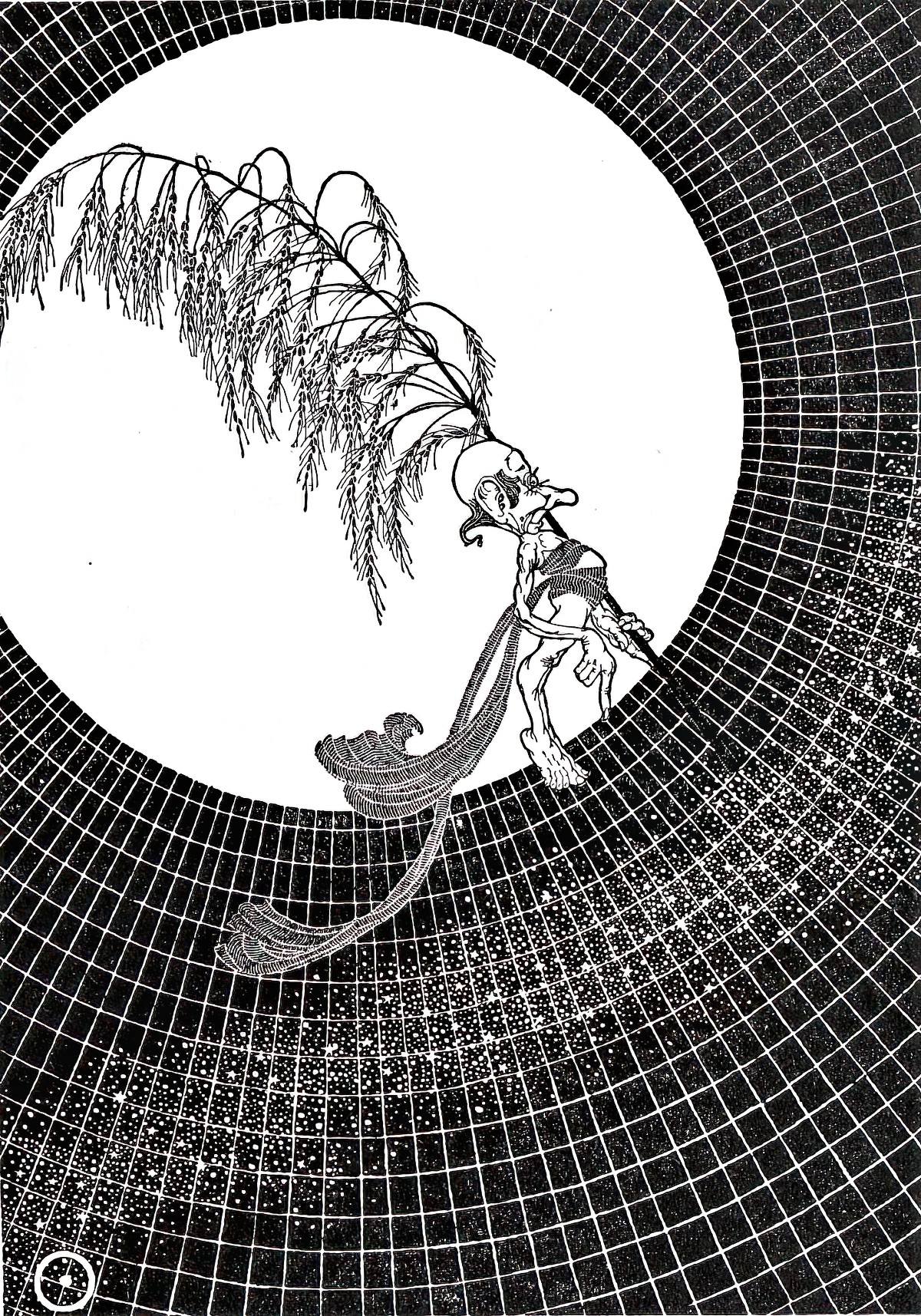

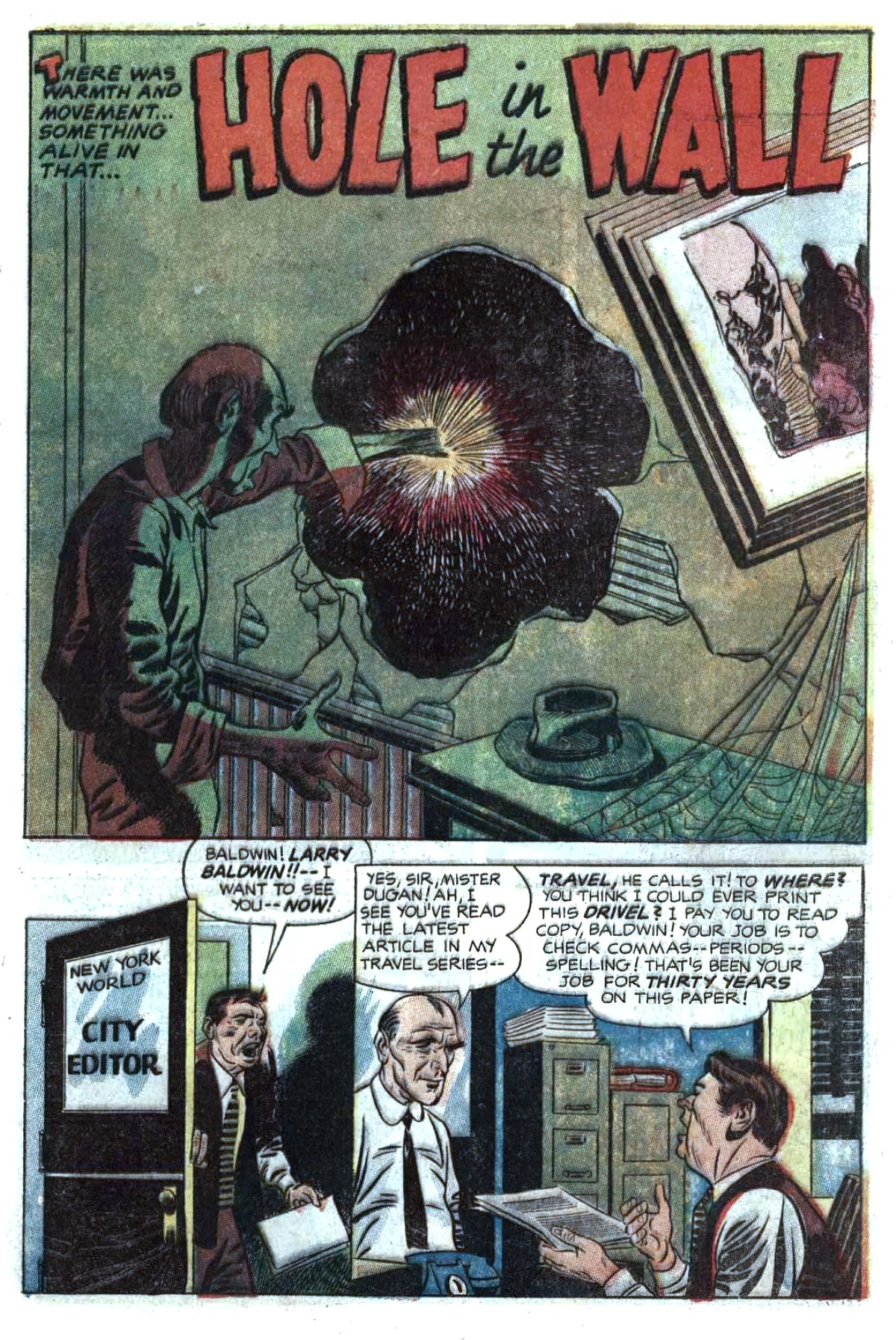

Be careful what you cast out — the vacancy is quickly filled.

Austin Osman Spare

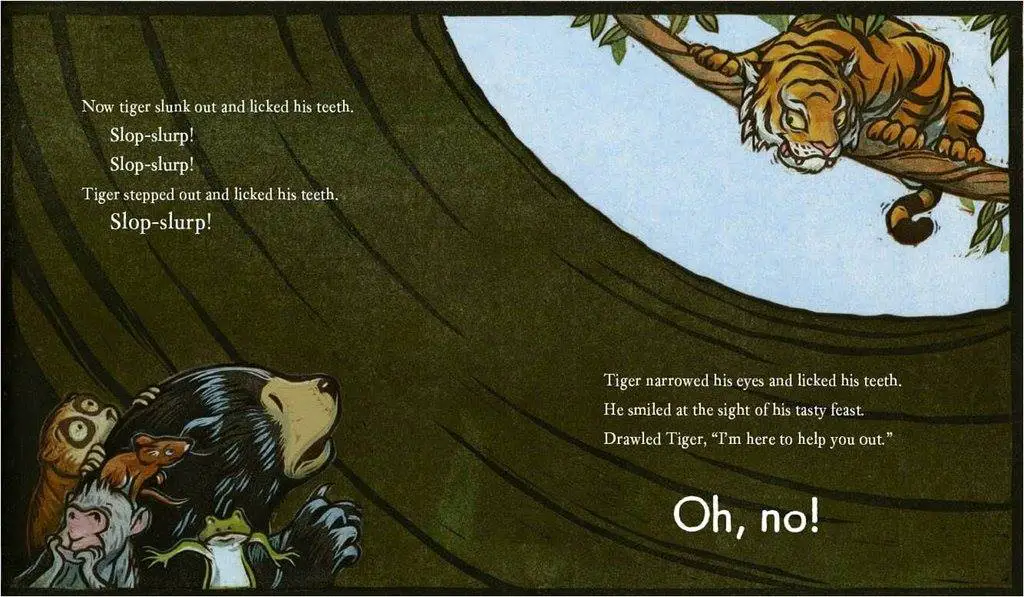

SAM AND DAVE DIG A HOLE

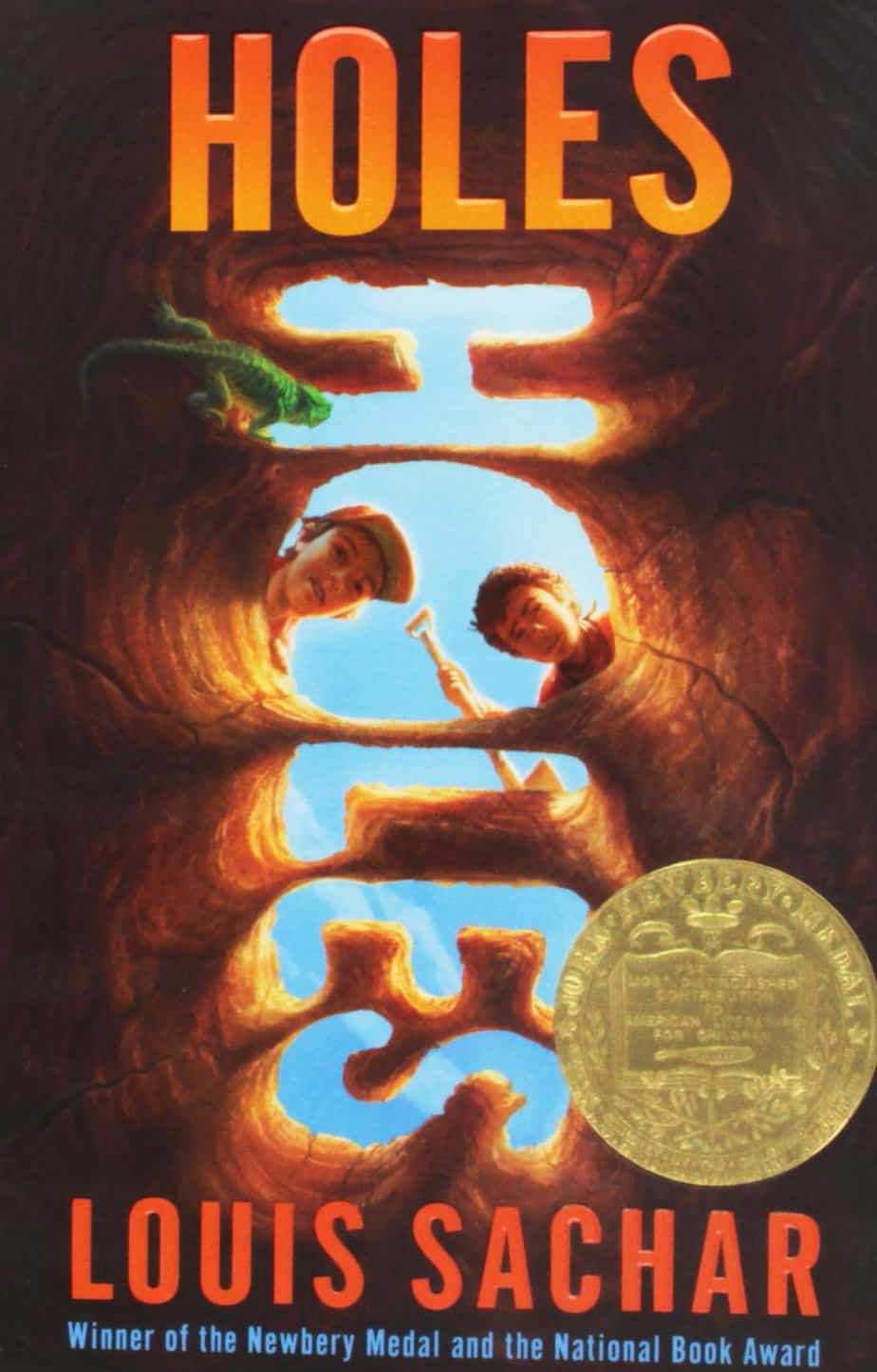

HOLES BY LOUIS SACHAR

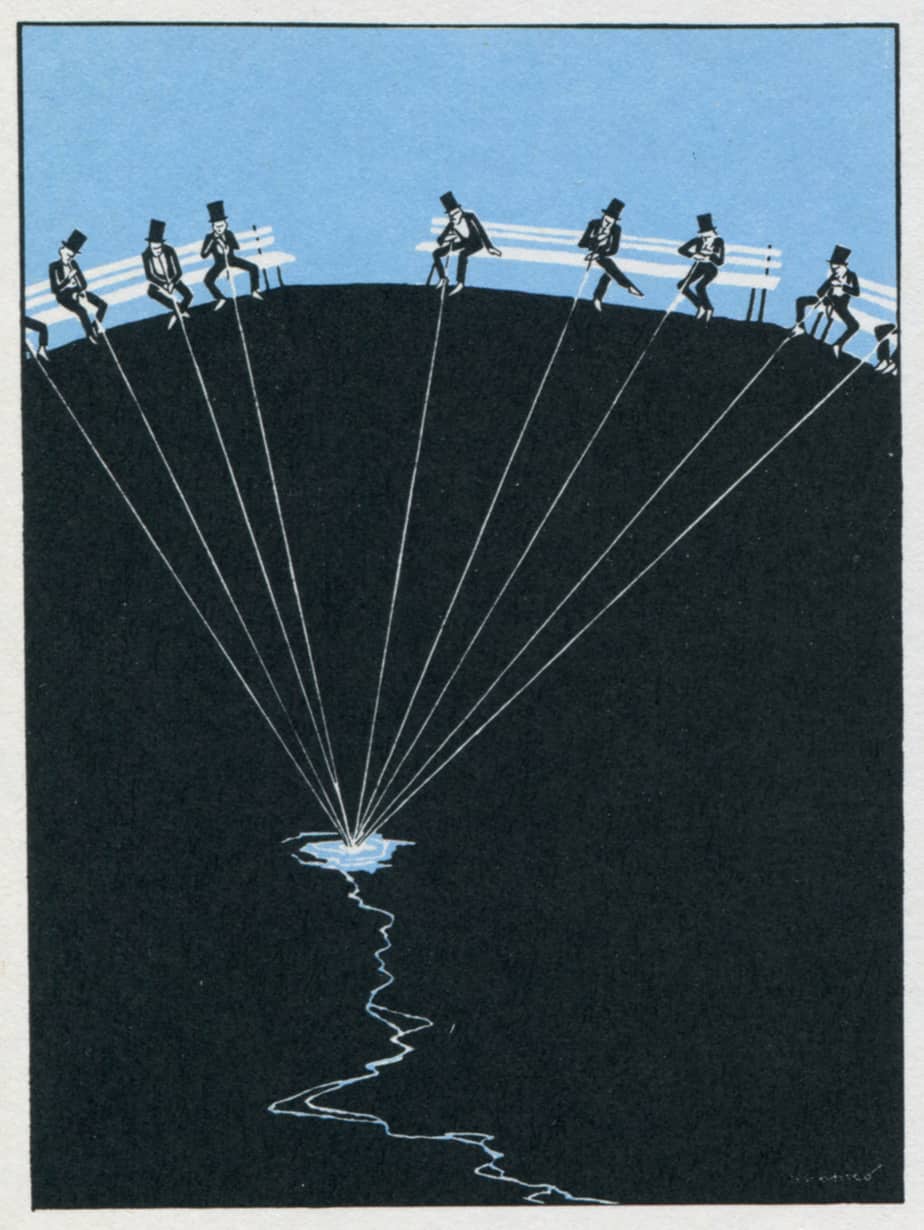

Stanley Yelnats is under a curse. A curse that began with his no-good-dirty-rotten-pig-stealing-great-great-grandfather and has since followed generations of Yelnats. Now Stanley has been unjustly sent to a boys’ detention center, Camp Green Lake, where the boys build character by spending all day, every day digging holes exactly five feet wide and five feet deep. There is no lake at Camp Green Lake. But there are an awful lot of holes.

It doesn’t take long for Stanley to realize there’s more than character improvement going on at Camp Green Lake. The boys are digging holes because the warden is looking for something. But what could be buried under a dried-up lake? Stanley tries to dig up the truth in this inventive and darkly humorous tale of crime and punishment—and redemption.

Holes is a middle grade novel by Louis Sachar, first published in 1998. This book’s Lexile measure is 660L and, in America, is frequently taught in the 6th to 8th grade. The themes and ideas are more complex than the grammar and vocabulary, making this a Hi/Lo reader (high interest, low reading age).

The sentence structure, humour and general blokiness of Holes reminds me of the stories of Paul Jennings, who was writing popular middle grade fiction here in Australia in the 1980s and 90s. Holes feels like a full-length Paul Jennings tale. Both descend from the tall tale tradition.

The first in the trilogy, “Sideways Stories from Wayside School,” was published in 1978. Like its sequels, the book revolves around a teacher named Mrs. Jewls, a recess supervisor named Louis, and a gang of sensitive and unruly students. With their clipped, manic chapters, the books, which have sold roughly nine million copies, satisfied an early literary attraction toward absurdity and irregular rhythms

Sachar is kind to his characters, but in a way that involves letting them be extremely rude to one another. I had never read anything that had both a surfeit of heart and an absence of sentiment.

It’s high-concept, slightly menacing world-building—Shel Silverstein with hints of Barthelme and Borges.

That knack for pattern and recurrence, plus Sachar’s ability to fit odd pieces together, make possible the central mechanism of his best-known book, “Holes,” which won a Newbery Medal, in 1999, and was later made into a movie, starring Shia LaBeouf. (Sachar wrote the screenplay.) “Holes” is set at a black-site boot camp for troubled children, who must, as punishment, dig holes in the desert for months on end. The protagonist is a boy named Stanley, who has a misfit friend named Zero. Scenes of their hard labor give way to stories about how each of the kids ended up in the clink. There’s another plot, set in the eighteen-eighties, about a white teacher who falls in love with a black onion seller; and there’s a country legend concerning an outlaw who leaves lipstick kisses on her murder victims; and a tale from eighteen-fifties Latvia involving a marriage, a pig, and a curse that ties all the stories together. It took Sachar several full revisions to make all the strands feel connected, he told me recently. By the end, every detail is intertwined. The old curse threading the motley stories is broken, and rain falls on the desert for the first time in a hundred and ten years.

The New Yorker

After the author puts the reader in audience superior position by explaining the nature of the camp, the focal character is revealed to be Stanley Yelnats. Stanley is ostracised because he is fat. He is also constitutionally hopeful, which, the narrator explains, is to his detriment. If he weren’t so hopeful, his hopes might not be dashed quite so often. A “Gypsy” has put a family curse on one of Stanley’s male ancestors, which affects them all to this day. (The 1990s was the last decade in which it was considered acceptable to utilise Travellers as mysterious ancient opponents.) Now, Stanley has found himself in the wrong place at the wrong time and is being sent to a camp for bad boys. He’s at another disadvantage: Although he knows he’s going to a camp for bad boys, he has no idea how desolate this place actually is.

Stanley’s ‘crime’ is highly unusual: A bully kid dropped a sneaker onto his head as he emerged from an underpass. Thinking this would solve the mystery to his scientist father’s desire to find a use for old sneakers, he ran home with it. This was considered stealing. The scene calls back to the story of Chicken Licken, who also believes something Providential is happening when struck on the head by something from above. Stanley is as hapless as a chicken. In this part of the tale, another irony is set up: Nobody believes Stanley when he proclaims innocence, but nobody believes the real story, either.

Upon arrival at camp, Stanley must judge for himself which of the adults he can trust, and which he must avoid. The reader is invited to make these judgements alongside Stanley.

Mr Sir is a cartoon character who has recently replaced his smoking habit with eating an entire sack of sunflower seeds per day. (Does this induce some kind of hallucination?) It’s useful to give comic villains an eccentricity like this. Now Mr Sir’s dialogue can be punctuated with the spitting-out of husks.

“You’re not in the Girl Scouts anymore… This isn’t a Girl Scout camp.”

This line cements Mr Sir as a scary man who is about to induct Stanley into a world of toxic masculinity. The youngest readers will likely pick up that much, even if they can’t articulate it. The danger in writing lines like these: There’s no on-the-page critique of this man’s presentation of girls as weak. As much as the reader is encouraged to despise Mr. Sir, the reader is not necessarily going to question his take, when the take is in fact the dominant one.

Covert ideology is always more dangerous than overt ideology. Besides, this is unpleasant for girls to read. What’s comedy for boys isn’t going to work for girls, not when girls are the butt of the joke.

Mr Sir has a gun, but the problem faced by middle grade authors is this: Storytellers don’t actually want kids to think the empathetic main character is going to get shot. “Don’t worry, it’s for yellow lizards,” says Mr Sir to Stanley. “I wouldn’t waste a bullet on you.” This line takes care of that particular worry, while still allowing for a little anxiousness about Mr Sir’s volatility. This is a take on what I call Chekhov’s Toy Gun.

Mr Pendanski is not as ‘scary looking’ as Mr Sir. Mr Pendanski tells Stanley that the real bad guy is The Warden. Mr Sir is only scary because he recently gave up smoking. Can Stanley trust this?

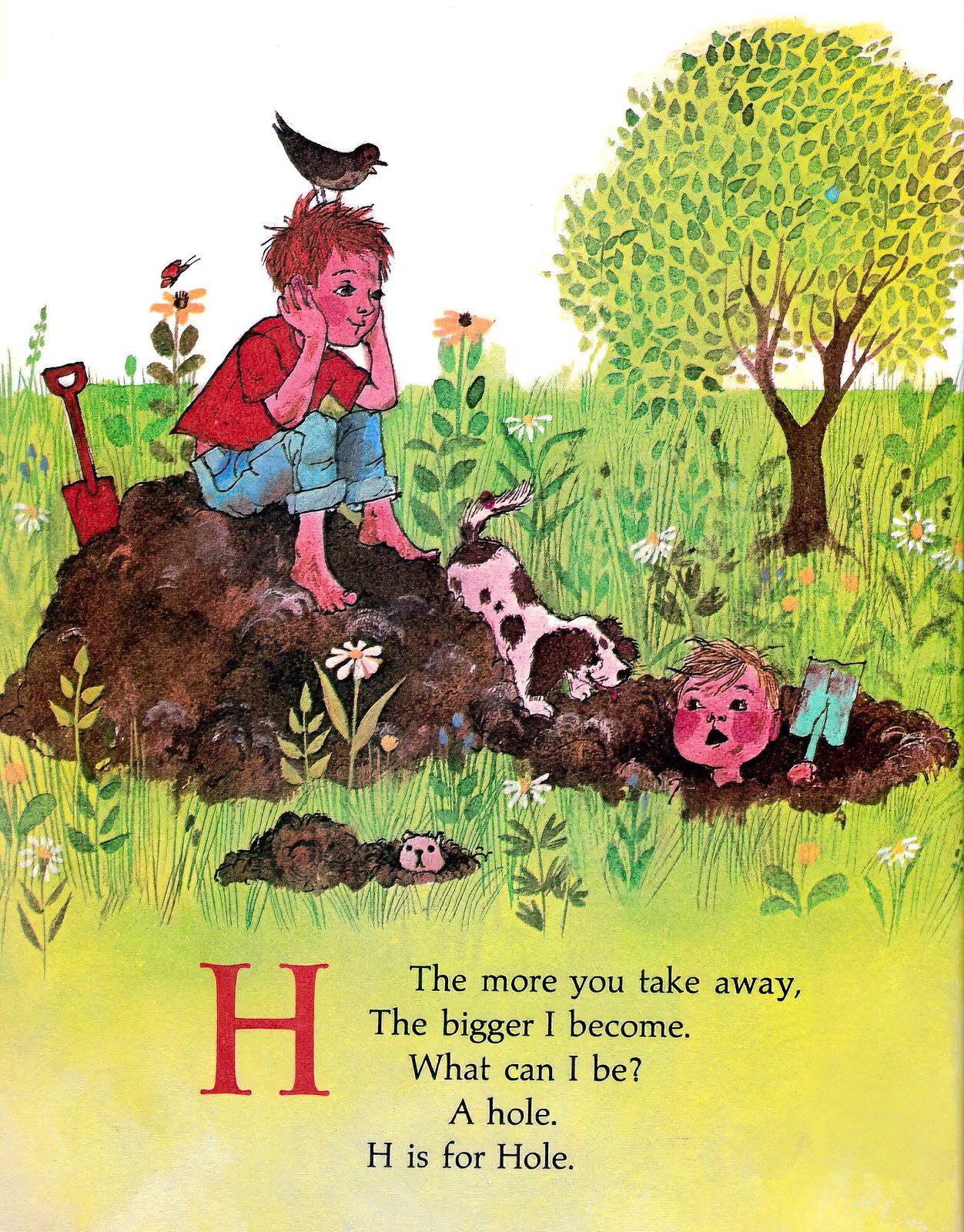

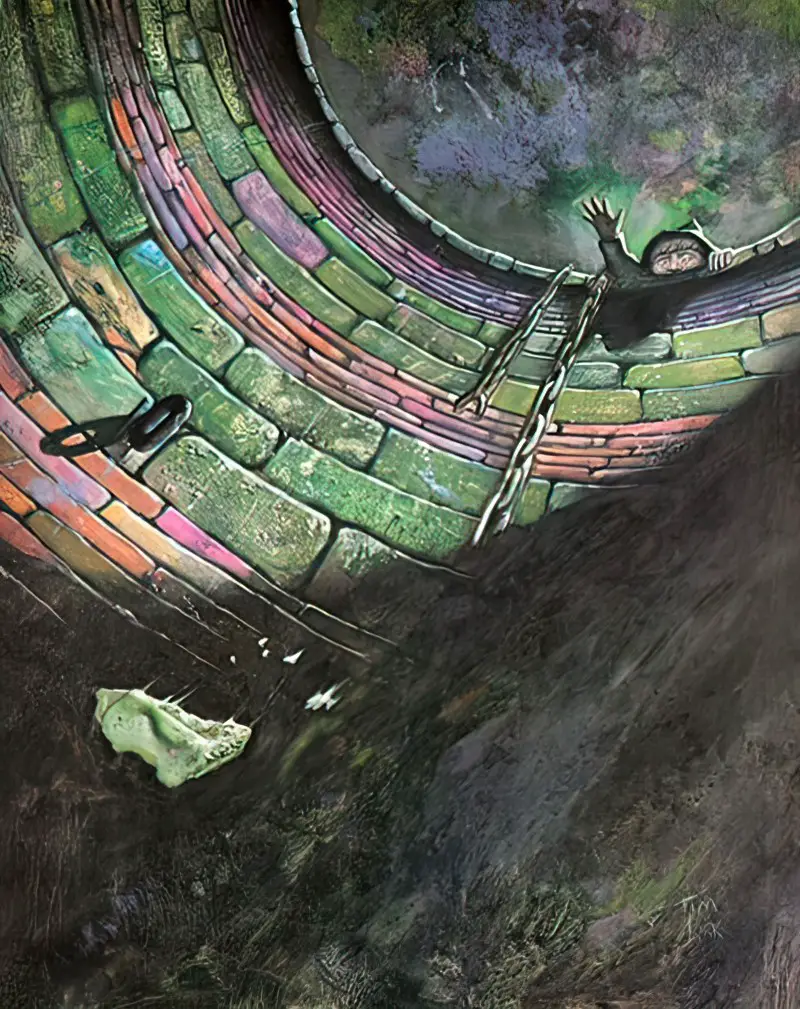

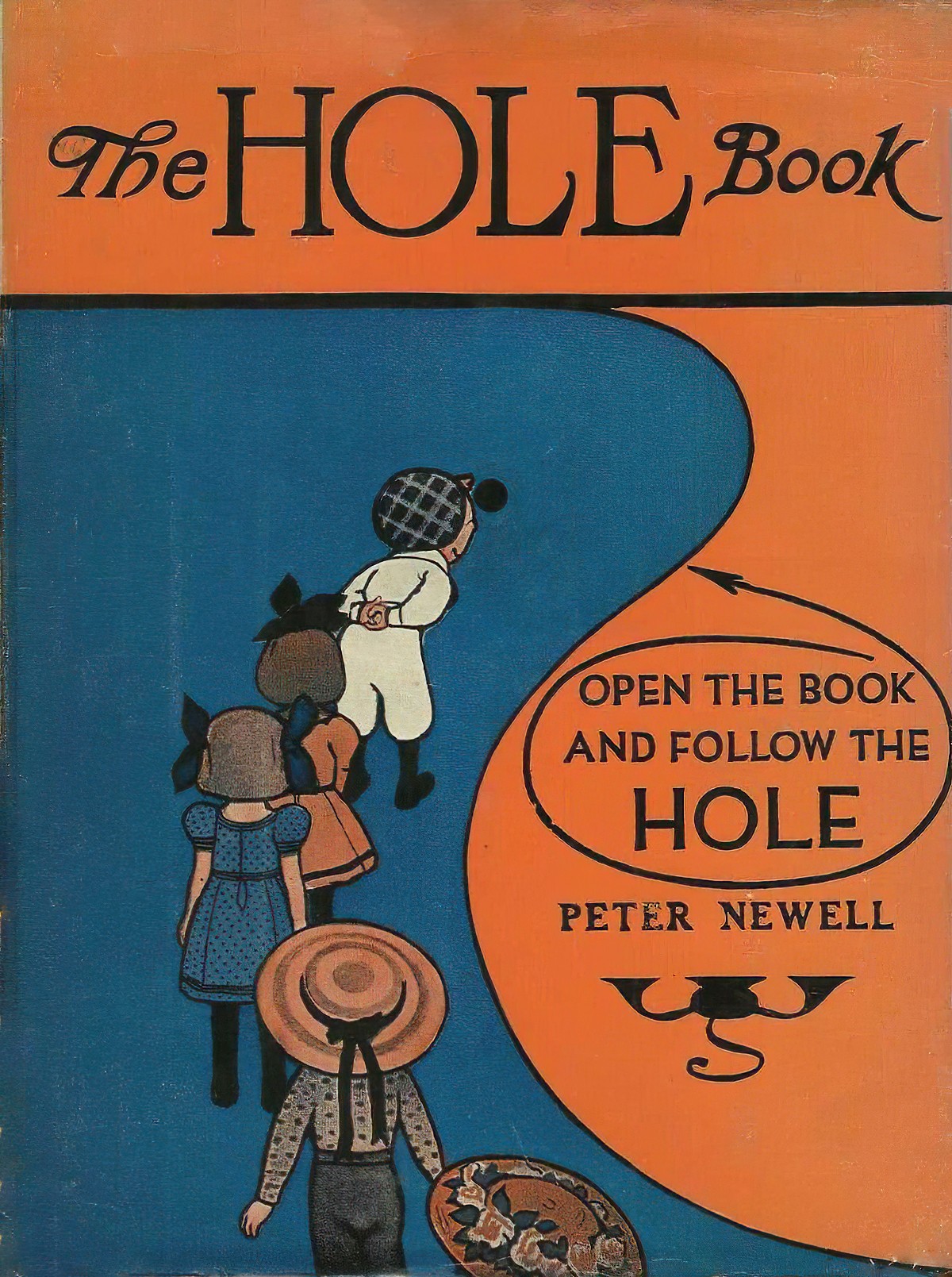

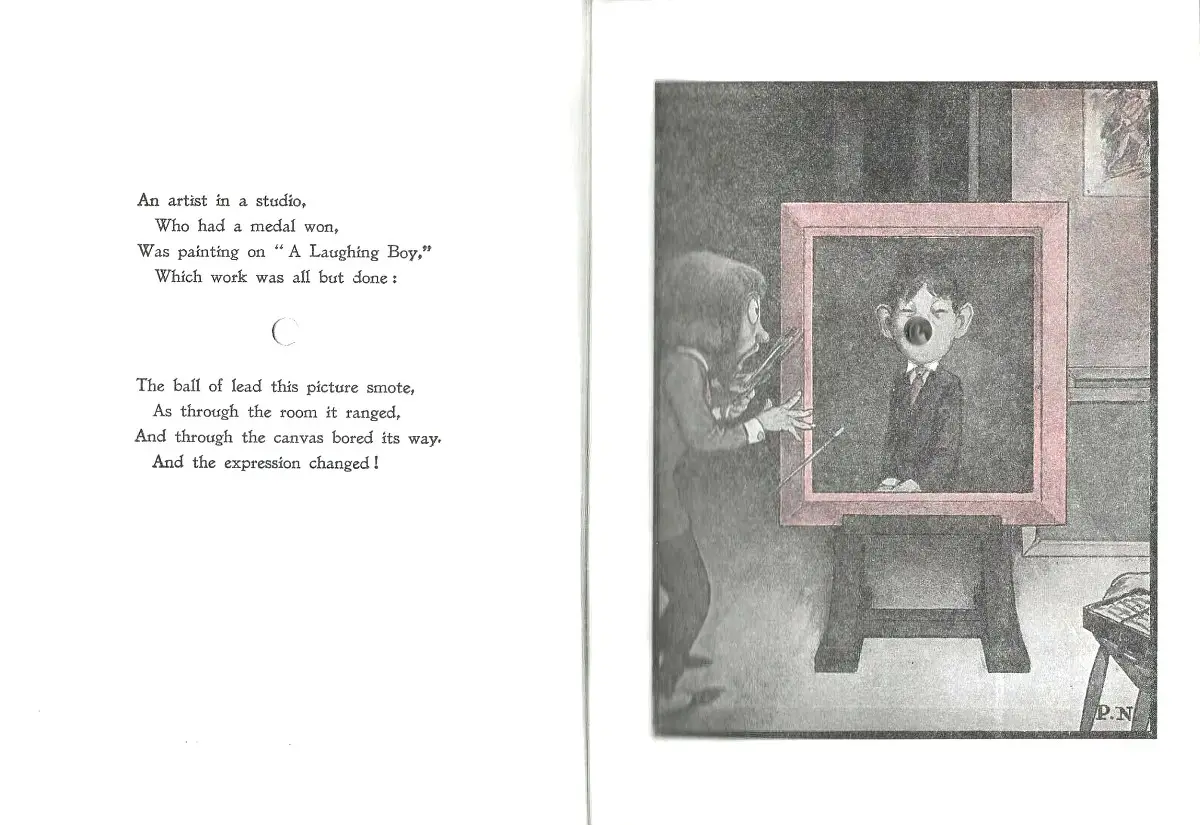

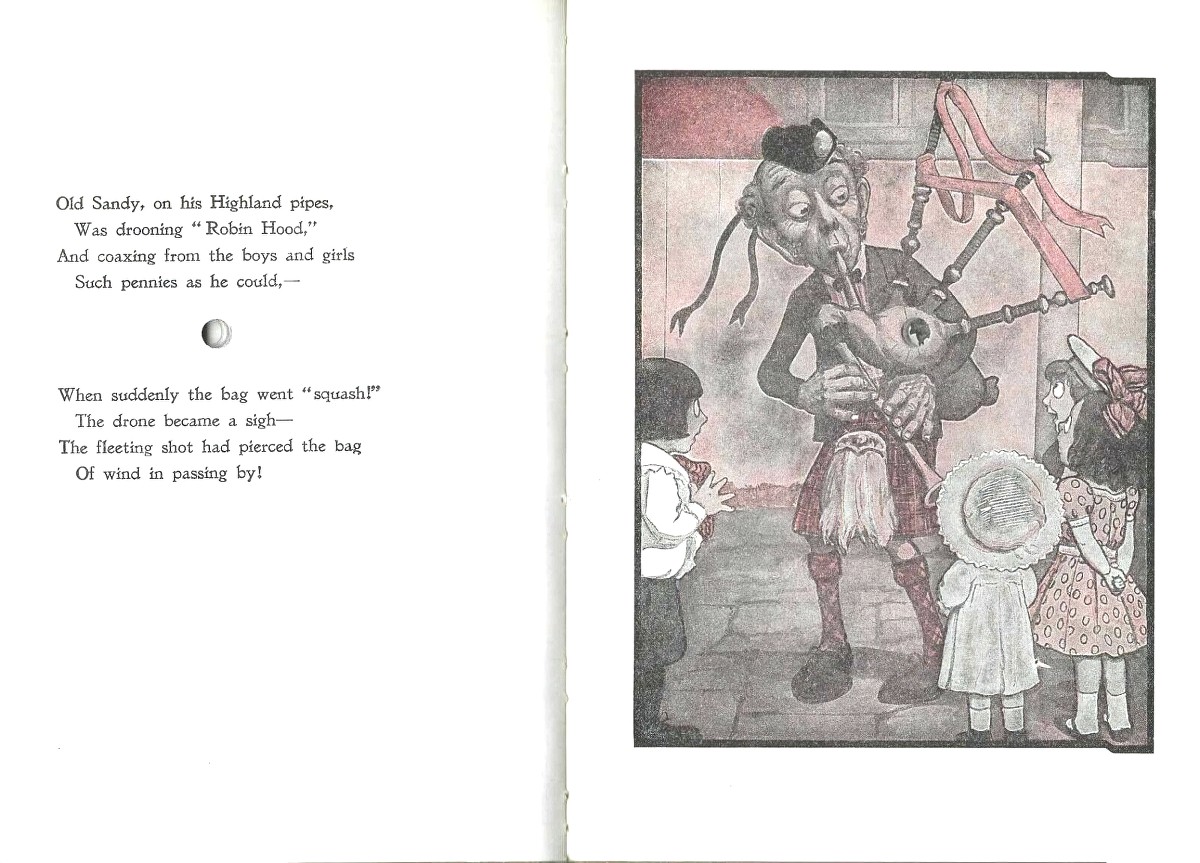

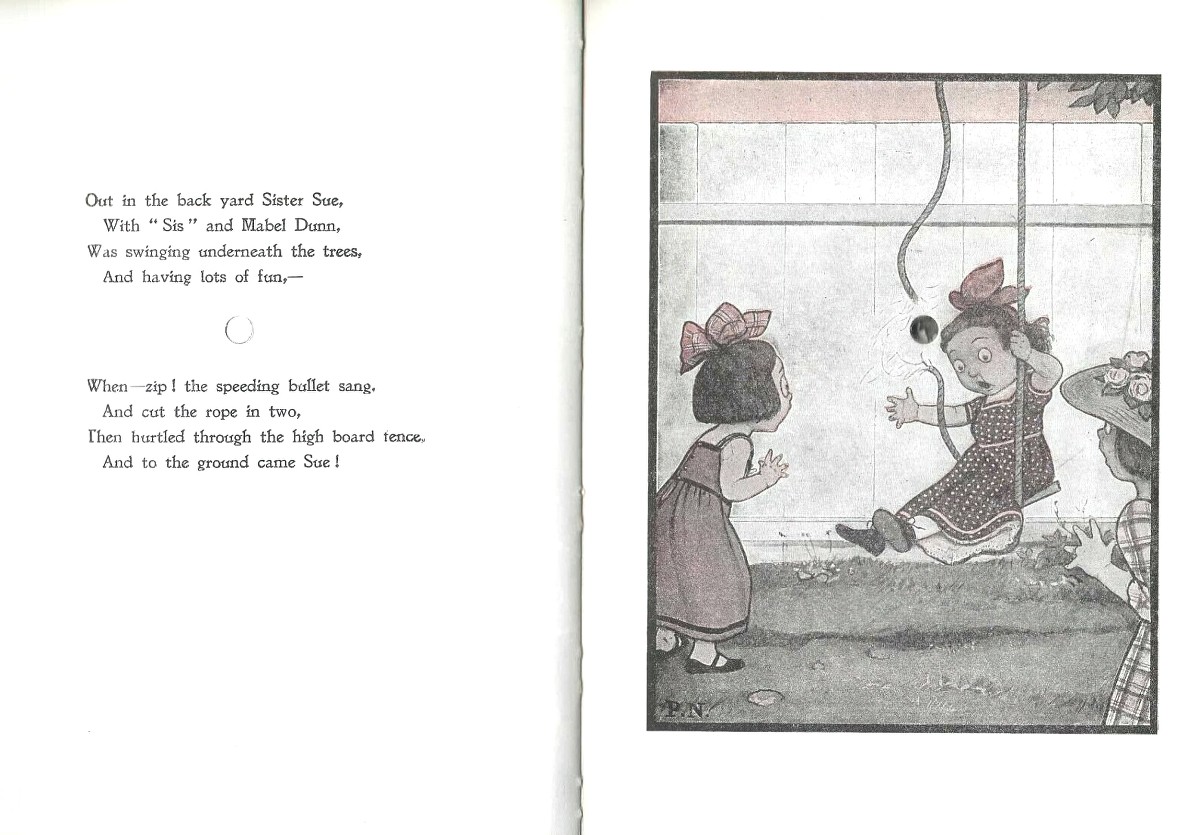

The Hole Book by Peter Newell, 1965, turned a book into a play object, reminding the readers that they are reading a book, and the book is part of the artifact of the story. This is therefore a 1965 example of metafiction. This Book Just Ate My Dog is a later example of what became a much stronger picture book trend after the turn of the millennium.

Every Pore on Your Face Is a Walled Garden A close examination of human skin found that each pore had a single variety of bacteria living inside.

Dr Karl, commenting on this NYT article