Released in 1960, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho is a significant film in the history of cinema. This psychological thriller made a lasting impact with its unique storytelling and innovative cinematic techniques.

While the film is notorious for its shower scene and depiction of transgender and mental illness, it does a few things right.

1. Hitchcock’s Psycho was the film that assisted in ushering the transitional phase of film noir to neo-noir.

Some fans of film noir point in the direction of Welles’ film as the final “film noir”.

For more on the definition of noir, see this post.

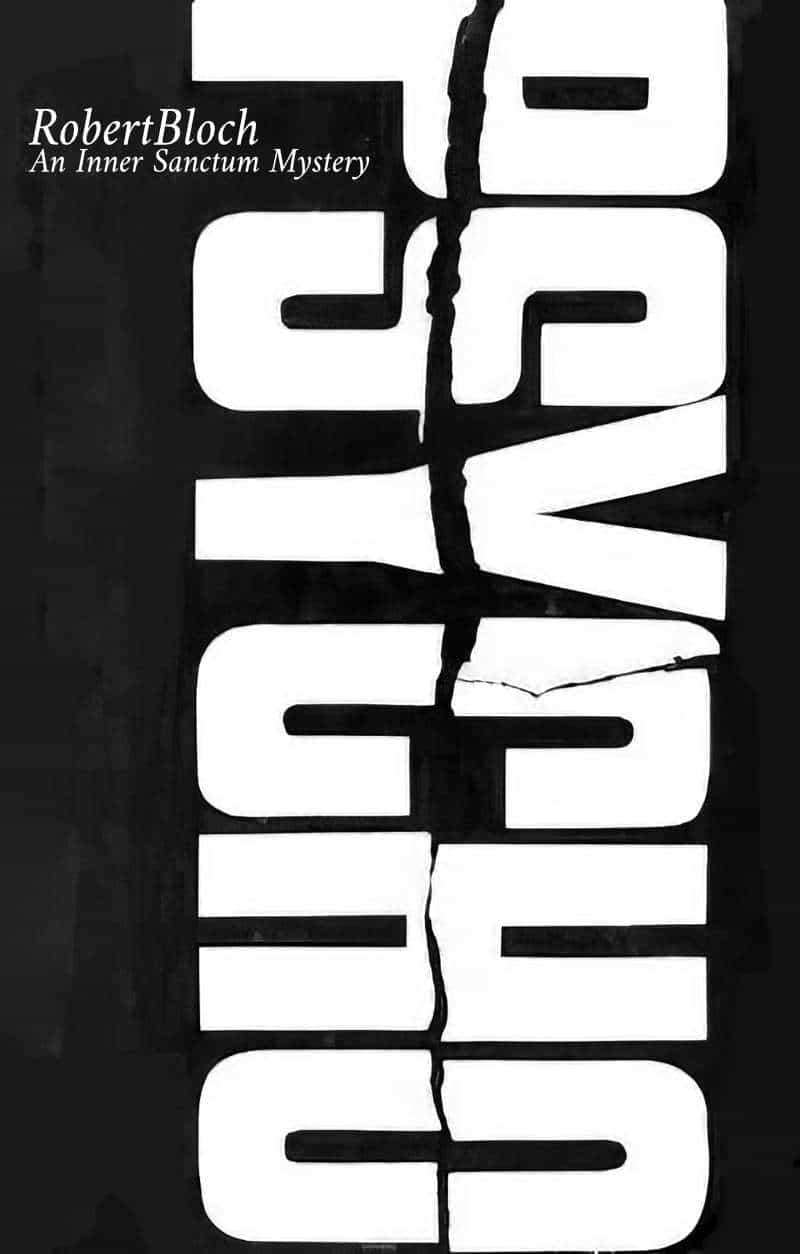

2. The film is based on the 1959 novel of the same name by author Robert Bloch.

Bloch (1917 – 1994) remains best known for Psycho but wrote prolifically for 60 years — everything from crime to science fiction. H.P. Lovecraft was a favourite author of his.

If you have a first edition of this book it’s worth about $3000 as of 2023.

3. Hitchcock’s Psycho was a trailblazer when it came to movie trailers.

THE PSYCHO TRAILER: A STAND-OUT FILM TRAILER OF ITS ERA

We’re all in our private clamps, trapped in them, and none of us can ever get out.

Psycho (a line utilised in the trailer)

Trailers were initially to make you want to come back and see the next instalment of something, to make you intrigued about what will happen. So they might show you some of the story but then they’ll say, “What will happen to our hero?” or something like this. That thread of intrigue, you can follow it through the best trailers into the 1940s.

The Citizen Kane trailer is a really interesting one to watch because it’s just Orson Welles saying, “What’s the real truth about Charles Foster Kane? I wish you’d come to this theatre when Citizen Kane plays here.”

[Voiceovers] ask all these intriguing questions are [audiences] are like “I don’t know, I wanna find out!”

It’s a little bit like what horror trailers do now where it’s like, “What is going on in this weird house with these weird people? I’m curious!”

A really famous example is the trailer for Psycho. Alfred Hitchcock is walking through the Bates Motel and he’s sort of telling you all the stuff that happened in this place. And he’s almost giving away what is about to happen but stops short of actually telling you what is happening here.

That’s a really effective way to get people to buy a ticket because this was at a time when the only way you were going to find out is if you bought a ticket and went and saw it. You couldn’t read about it on Wikipedia, you weren’t able to rent it three months later and see it in your house. You didn’t have a television. [The theatre] was the way you were going to see the movie.

And then there’s this move that’s sort of funny in, what you might call avant garde trailers in the sixties and seventies when Hollywood was moving from its epic era into small, nimble films which appealed to younger people. Now you see trailers which are just images, just words, just an experience like ‘You’re gonna come see this movie and you’re gonna have this feeling.’

And then when we move into the blockbuster era, particularly with Jaws, Jaws is like the biggest commercial product ever and a huge, huge hit in the way it got people in the door. [The Jaws trailer] basically told you everything that was going to happen in the movie. Like, everything. [This kicks off] a long era in which trailers tell you everything about the movie. The original Star Wars movie trailer tells you everything about the movie. And you go because you like the idea of seeing that.

Today Explained, a Vox podcast, 19 Dec 2022, in which Alissa Wilkinson makes a case for us all to stop watching modern movie trailers because they are doing the film-going experience no favours at all, spoilering what should not be spoiled, or promising a movie which doesn’t match the product at all.

What does she think when trans rights and feminism butt up in this way?

“I think, what are people afraid of? I think they may have seen Psycho at too formative an age. They’re afraid of somebody dressing up like their dead mother and stabbing them in the bathroom or something.”

Margaret Atwood: “If You’re Going To Speak Truth To Power, Make Sure It’s the Truth”

Psycho is noteworthy for its violence against “un-respectable women. Marion is set up as a typical sexual woman figure, from the first intrusion of the camera into the hotel window behind which she has sex with her married lover. In Hollywood cinema, such extra-marital “transgressions” have remained a death-sentence for women—a good example is Adrian Lyne’s Fatal Attraction (1991).

Gothic Forms of Feminine Fictions by Susanne Becker

4. Psycho is an example of Gothic horror, and Gothic horror is ‘family horror’.

That may sound strange, but Gothic horror relies on feminine monsters: murderous nannies who infiltrate the home, women who are monsters, houses which are feminised, women’s pregnant bodies compared to a house, you name it.

This applies to contemporary Gothic horror as much as to classic Gothic horror. Psycho is considered a turning point—the transition ‘from the family or marital comedy of the 1950s to the family horror film’ (Robin Wood, 1986). Three years after Hitchcock’s Psycho came out, Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique, which is also about a feminine transition, from ‘mystique’ to genuine empowerment.

5. In 1960, “psycho” did not mean what it means today.

Today we consider ‘psycho’ a shortened form of ‘psychopath’, which describes an adult with callous and unemotional traits and violent tendencies.

The word ‘psychopathology’ used to have a much broader meaning, referring to a disease of the mind.

By this broader definition, we can understand the character of Marion to also be ‘psycho’ — by stealing the $40k she herself went momentarily ‘mad’. Then she met the ultimate version of herself in Norman Bates — the classic ‘shadow in the hero’ storytelling technique.

See also: Psychopaths, Sociopaths and Narcissists in fiction, in which I investigate the difference between ‘sociopath’ and ‘psychopath’.

6. Psycho plays into chrononormativity.

Marion’s problem is that she is an elderly woman, at the age of 35. She’s desperate to get married.

In Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, Marion is motivated to set the film’s action in motion that is, steal $40,000, and run off with it in order to pay off her boyfriend’s debts so he can marry her in part because she is over 35, and desperate to get married. The film was released in 1960, and audiences believed this character motivation. When Gus Van Sant remade the film shot-for-shot in 1998, with a younger Anne Heche as Marion, the motive vanishes. Aside from the age of the character, an audience in 1998 was not inclined to believe a woman would commit a felony to avoid being an old maid.

TV Tropes, “Old Maid”

As evinced by Marion Crane’s motivation to hurry up and get married lest she become an old maid, the film Psycho relies heavily on the notion that people have to do certain things by certain ages, otherwise there’s something wrong with them.

It’s fairly well-known by now that Psycho did absolutely nothing for trans people and people with mental illness, or gay men for that matter, and the woman is killed off after an objectifying shower scene which marries violence and female sexuality. (A Hitchcock speciality, which unfortunately carried over into the abuser’s real world interactions with women, as Tippi Hedren has told us.)

7. Norman Bates, to this day, remains the avatar for single men who have ‘failed’ to leave home.

That doesn’t mean men are off the hook. Psycho did nothing for men, and when men en masse feel masculinity is hard won, that does the entire culture no good.

How is Psycho bad for men? Well, the film is hardly alone in this, but Norman Bates is presented as a pathetic figure who is pathetic because he has never left home, never untied himself from his mother’s apron strings, as the saying goes.

Chrononormativity is the word we can use to illuminate the cultural expectations heaped upon us all regarding when is the correct age to distance ourselves from our natal families and make our own way in the world. (There’s no such thing as ‘making our own way’ in the world. We all live in a society, and if we’re not helped by our mothers, we’re surely helped by our mentors, friends, lovers, partners, customers, employers and so on.)

Surely it’s time to apply heavy critique to the notion that adulthood has tickets to entry, and includes doing certain things at certain times. When it comes to leaving home, it is more important than ever to critique this in an era when real estate prices have shut an entire generation of young people out of home ownership.

But we’re nowhere near that yet. Here’s an excellent example of chrononormativity from a contemporary show: Disappearance at Lake Elrod (2020).

In Episode One, two empathetic female characters strike up conversation at a bar. The main character, Charlie, whose daughter disappeared a year earlier, has given up waiting for police to find her daughter’s killer and is about to amp up her own detective efforts. She’s watching the news on the bar TV, and learns another girl from Elrod has gone missing. This is the daughter of an influential white man who confronts the camera with his own mother. (Police are likely to take this guy’s daughter’s disappearance more seriously, because of who he is.)

AMY: Something creepy about a grown ass man still living with his mama, don’t you think?

CHARLIE: Yeah, I guess.

AMY: Just sayin, I watched Psycho and I see a resemblance.

Episode One, Disappearance at Lake Elrod, 19.50

8. The Psycho house is similar to what is now called ‘Second Empire Style’.

For more examples of this style in film and fiction, and how to spot it when you see it: What architectural style is the house of Psycho?

9. Alfred Hitchcock was a notorious abuser, especially of women.

Behind the Bastards podcast has done an excellent two parter on that.

- Part One: Alfred Hitchcock: The Director Who Randomly Tortured People

- Part Two: Alfred Hitchcock: The Director Who Randomly Tortured People

Conflicting matters, even the Harvey Weinsteins of this world sometimes get things right, even in a work of art which is a net loss for culture.

As an example of something Hitchcock got right in this film: Marion is moving through the world highly aware that the masculine gaze is on her, as a single beautiful woman out in the world alone. Whether Hitchcock understood this aspect of being a woman is up for debate. I suspect he was instead portraying the mindset of a woman who knew she had done something wrong and was on edge because she knew the police would be on her tail. Either way, Marion’s state of mind is a refreshing departure from how woman victims were generally portrayed in this era: Naïve, innocent and stupidly blundering into dangerous situations which any regular woman would instinctively avoid. We can say this of Marion : At least she had some wits.

10. Bernard Herrmann wrote the memorable score to Psycho even though Hitchcock didn’t want it.

Alongside Jaws, the Psycho soundtrack is cinema’s most memorable and identifiable.

Originally the plan was to have no music over any of the murder scenes. (Hitchcock adapted Daphne du Maurier’s The Birds entirely without music at all, in a strong departure from the norm of the day.) However, composer Bernard Herrmann disagreed. He felt music was required.

They first cut the scenes without music. Hitchcock was fine with no music. But Herrmann asked Hitchcock to at least listen to the idea he had in mind.

As soon as Hitchcock saw the scene again with Herrmann’s music, he agreed that the scene absolutely needed the score.

And because Hitchcock was an utter narcissist himself, he rewrote history and denied saying he didn’t want the music.

Source: Bernard Herrmann on the music for Hitchcock’s Psycho

Let’s remember this aspect of Hitchcock when we give him credit for those excellent movies: He was surrounded by many talented people, and took a disproportionate amount of credit because he was director.

RESOURCES AND FURTHER READING

Psycho with Leila Latif, The Bechdel Cast, 12 October 2023, a podcast about the portrayal of women in movies hosted by Caitlin Durante and Jamie Loftus.

Episode 60 of the Then Again Podcast: Alfred Hitchcock’s Art of Suspense. “Special guest and movie buff Matt House discusses the techniques and methodology of Alfred Hitchcock’s thrillers.”

Psychoanalysis and Hidden Narrative in Film BY Trevor C. Pederson (2020)

The revelation that Norman Bates’ character had been his mother all along, suggests a framework of reading a film as having symptom characters who are excised to create a latent plot. The symptom character’s behavior or inter-relations are then transcribed to an ego character. This is a shift in the tradition of literary doubling from hermeneutic intuition to a formal methodology that generates data for the unconscious.

New Books Network

Madness at the Movies: Understanding Mental Illness through Film

The study of classic and contemporary films can provide a powerful avenue to understand the experience of mental illness. In Madness at the Movies: Understanding Mental Illness through Film (Johns Hopkins UP, 2023), James Charney, MD, a practicing psychiatrist and long-time cinephile, examines films that delve deeply into characters’ inner worlds, and he analyzes moments that help define their particular mental illness.

Based on the highly popular course that Charney taught at Yale University and the American University of Rome, Madness at the Movies introduces readers to films that may be new to them and encourages them to view these films in an entirely new way. Through films such as Psycho, Taxi Driver, Through a Glass Darkly, Night of the Hunter, A Woman Under the Influence, Ordinary People, and As Good As It Gets, Charney covers an array of disorders, including psychosis, paranoia, psychopathy, depression, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and anxiety. He examines how these films work to convey the essence of each illness. He also looks at how each film reflects the understanding of mental illness at the time it was released as well as the culture that shaped that understanding.

Charney explains how to observe the behaviors displayed by characters in the films, paying close attention to signs of mental illness. He demonstrates that learning to read a film can be as absorbing as watching one. By viewing these films through the lens of mental health, readers can hone their observational skills and learn to assess the accuracy of depictions of mental illness in popular media.

interview at New Books Network

Psychoanalysis and Hidden Narrative in Film: Reading the Symptom

Psychoanalysis and Hidden Narrative in Film: Reading the Symptom (Routledge, 2018) proposes a way of constructing hidden psychological narratives of popular film and novels. Instead of offering interpretations of classic films, Trevor C. Pederson recognizes that the psychoanalytic tradition began with making sense of the seemingly inconsequential. Here he turns his attention to popular films like Joel Schumacher’s The Lost Boys (1987). While masterworks like Psycho (1960) are not the object of interpretation, Hitchcock’s film is used as a skeleton key. The revelation that Norman Bates’ character had been his mother all along, suggests a framework of reading a film as having symptom characters who are excised to create a latent plot. The symptom character’s behavior or inter-relations are then transcribed to an ego character. This is a shift in the tradition of literary doubling from hermeneutic intuition to a formal methodology that generates data for the unconscious.

Pederson continues the project of unifying competing schools into a single model of mind and offers clinical examples from his own practice for all its terms. Psychodynamic techniques that emphasize the importance of working with the body, the id, and the ubiquity of repetition are introduced. A return to Freud’s structural theory, in which complexes are anchored in the stages of superego development, is used to carefully plot and explain the social nature of the superego and its relation to authority in society (secondary narcissism) and the otherworldly (primary narcissism). Discrete phases of superego development and their ties to both the social and the id revive the grand promises of classical psychoanalysis to link with every field in the humanities.

New Books Network

THE CAMERA LIES

In The Camera Lies, published in 2020 by Oxford University Press, author Dan Callahan spotlights the many nuances of Hitchcock’s direction throughout his career, from Cary Grant in Notorious (1946) to Janet Leigh in Psycho (1960). Delving further, he examines the ways that sex and sexuality are presented through Hitchcock’s characters, reflecting the director’s own complex relationship with sexuality.

Dan Callahan is the author of Barbara Stanwyck: The Miracle Woman, Vanessa: The Life of Vanessa Redgrave, The Art of American Screen Acting, 1912-1960, and The Art of American Screen Acting, 1960 to Today. He has written about film for Sight & Sound, Film Comment, Nylon, The Village Voice, RogerEbert.com and many other publications.

Detailing the fluidity of acting—both what it means to act on film and how the process varies in each actor’s career—Callahan examines the spectrum of treatment and direction Hitchcock provided well- and lesser-known actors alike, including Ingrid Bergman, Henry Kendall, Joan Barry, Robert Walker, Jessica Tandy, Kim Novak, and Tippi Hedren. As Hitchcock believed, the best actor was one who could “do nothing well” —but behind an outward indifference to his players was a sophisticated acting theorist who often drew out great performances. The Camera Lies unpacks Hitchcock’s legacy both as a director who continuously taught audiences to distrust appearance, and as a man with an uncanny insight into the human capacity for deceit and misinterpretation.

New Books Network

THE PSYCHO RECORDS

Reading Laurence Rickels‘ The Psycho Records (Wallflower Press, 2016) gave me the urge to ask random strangers questions like: Are you haunted by Alfred Hitchcock’s famous shower scene? How do you feel about Norman Bates and other cinematic killers pathologically attached to their mothers? Does the thought of Anthony Perkins impersonating his dead mother and stabbing Janet Leigh make you uncomfortable and scared? Induce an uncanny sensation? Or does it seem dated, campy, even comical?

Rickels is interested precisely in these vicissitudes of the primal shower scene—what he calls the “Psycho Effect”—as it is taken up and therapeutically transformed by subsequent slasher and splatter films. It is not an accident that Hitchcock chose the shower stall as the site for his most famous moment of Schauer, the German cognate meaning “horror.” Traumatized American soldiers returning from World War II, dubbed “psychos,” were transposed into filmic psycho murderers straddling psychosis and psychopathy. Norman was perhaps the first such hero of variegated diagnosis.

In the 1970s and 1980s we encountered less exalted figures, like the cannibal Leatherface from Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Freddy Krueger of Nightmare on Elm Street fame. Still less sophisticated mass murderers followed: the zombies revived post-9/11 and, eventually, motive-less serial killers captured with the aid of “objective” forensics.

All these characters address the difficulty of separation and mourning, the pull toward fusion with Mother, the trauma of the cut, survival, and industrial killing—the intimate violence of Nazi doctors and the impersonal push-button battles of the Gulf War.

Many slasher and splatter films also tell the story of a newly emergent social category, subgenre, and audience member—the teen. Rickels devotes parts of the book to the postwar invention of adolescence, reading closely D. W. Winnicott’s papers on antisocial teenagers and juvenile delinquency. We all experience adolescence as a brush with psychopathy, Rickels tells us; for many it is the path not taken.

Perhaps this explains the appeal of the psycho, our “near-miss double.” In psychoanalytic terms, “there but for the grace of the good object go I.” [5]

Other topics covered in our interview and in The Psycho Records include vampirism, the couple and the crowd, scream memories, laughter, and substitution. As those familiar with Rickels’ books might expect, we often touch on one of the great themes of his oeuvre: mourning. Listen in!

New Books Network

THE BBC DRAMATIZATION

You may be able to unearth the BBC dramatization of Psycho somewhere e.g. on YouTube. Psycho was broadcast June 1998.