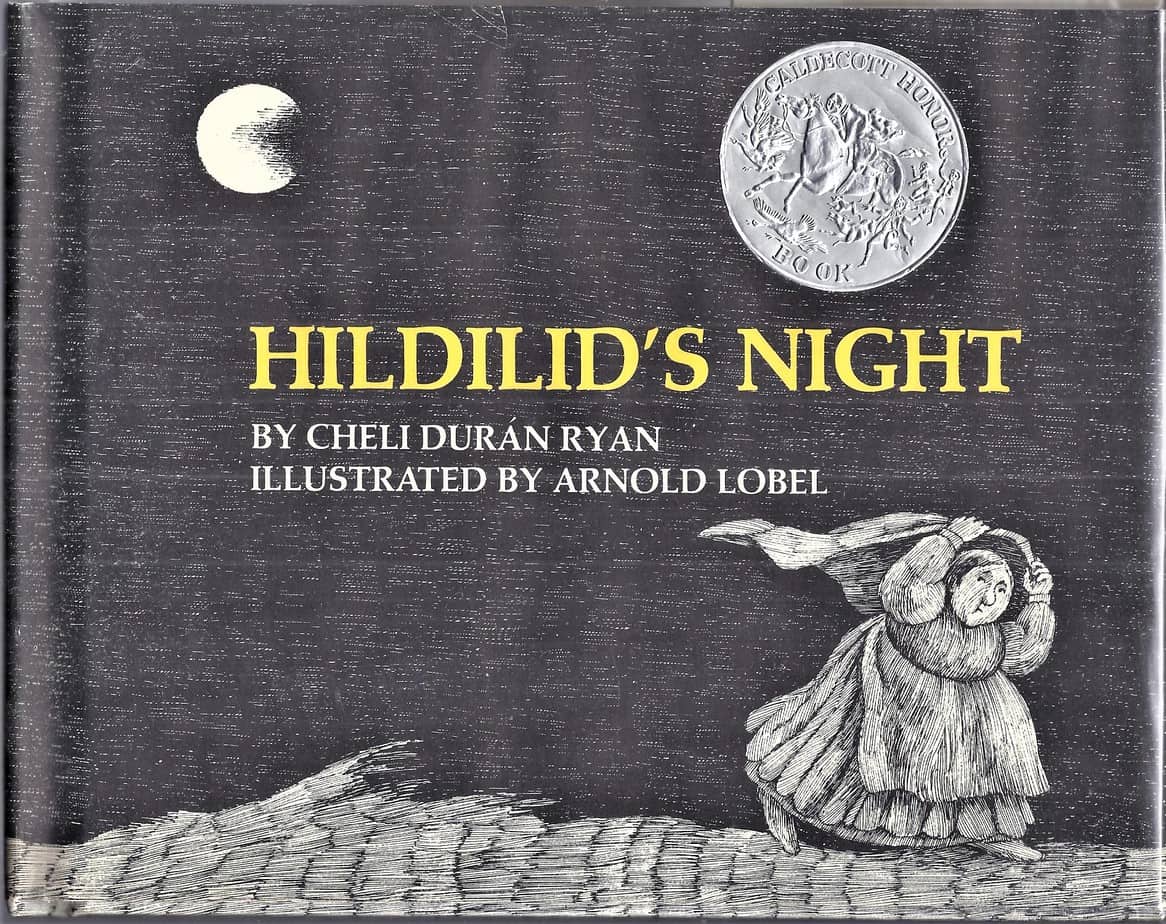

Hildilid’s Night is a 1971 picture book written by Cheli Durán Ryan, illustrated by Arnold Lobel. The illustrations are notable for being rendered entirely in black and white until the sun comes up at the end. This story feels like it’s based on an ancient myth.

STORY STRUCTURE OF HILDILID’S NIGHT

PARATEXT

In this Caldecot Honor picture-book, an old woman named Hildilid lives high in the hills and hates the night above all things. She tries capturing the night in a sack, tying it up with vines, shaking her fist at it, but the night takes no notice – until it disappears.

MARKETING COPY

SHORTCOMING

Hildilid has no distinguishing characteristics other than being afraid of the night. She has this in common with all of us, to a lesser or greater degree.

DESIRE

Hildilid wants the sun to shine 24 hours per day. On that deeper, psychological level, Hildilid does not want to feel the scary loneliness that envelops her once the sun goes down.

OPPONENT

The night, but really the darkness of the night stands in for any fear at all.

PLAN

The plan phase of this story takes up the vast majority of space and is what interests me the most. I recently read a few picture books with masculo-coded main characters who also made plans to deal with existential threat. In Creepy Carrots, the boy main character builds a moat and strong fence around a patch of carrot plants. In The Monster At The End Of This Book, Grover tries to prevent the reader turning pages first with rope, then with nailed planks of wood, finally with bricks and mortar.

The plans of these male characters reflect traditionally masculine activities — namely, building and construction.

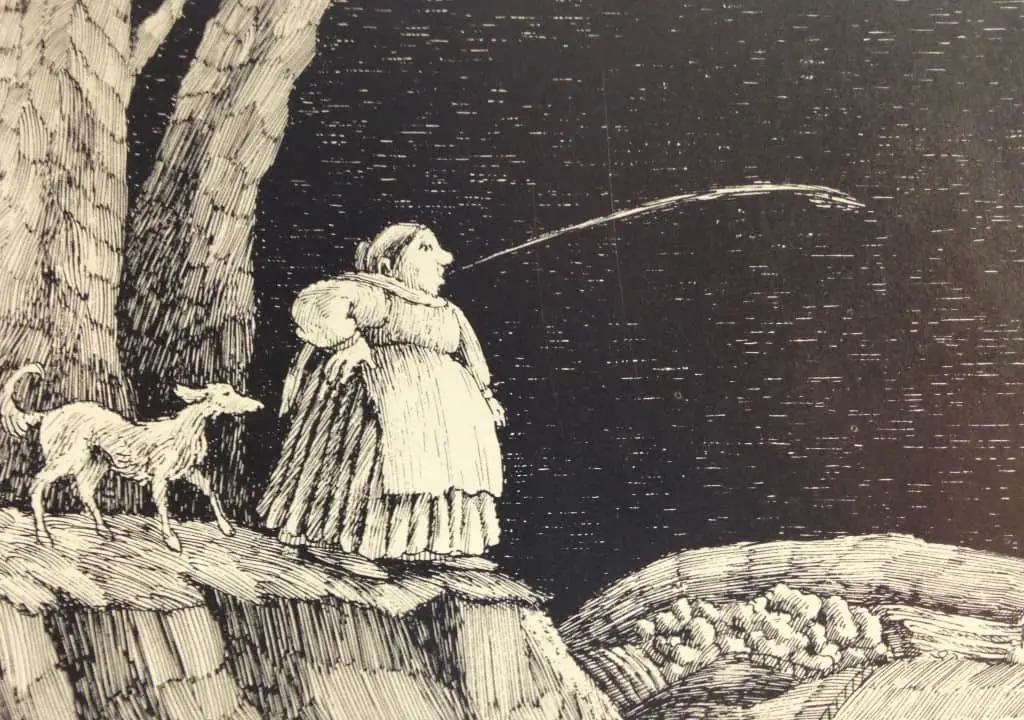

In contrast, Hildilid is a femme-coded character, and Hildilid’s fruitless plans are in line with what readers would expect of a woman. What does Hildilid do to try and stop the night?

- Sweeps, scours and whisks the dark out of her hut with a broom that she cuts from twigs. There is a long history of people using brooms to try and sweep out bad things of any kind.

- Pulls out her needle and sews a strong sack to fill the sack with night and empty it beyond the hills. Needlework is strongly femme-coded.

- Drags her cauldron to the fire to boil, simmer, burn etc. away the night. Likewise with the cooking. Hence the cauldron’s association with witches (and witches’ association with femininity, even though there have always been male witches as well).

- Gathers vines to tie up the night into a neat bundle, hoping someone will buy it at the market. (Grover and the boy in Creepy Carrots also make use of ropes. I guess roping things up is not a particularly gendered activity.)

- Shears the night like a sheep. This plan feels like the most fantasy-like, but nonetheless is related to the real work of housewives in the Medieval and modern eras, in which women were responsible for the entire clothing process from start to finish.

- Tossed the night to her old wolf hound (feeds the night to her pet)

- Tucks the night into her straw bed

- Tries to throw it down the well. This one is interesting because of all the symbolism around wells. When I was reading up about Early Modern history in England I was surprised how many girls and women have ‘drowning’ listed as a cause of death. We know from this (as well as from fiction), that women were the ones responsible for retrieving the daily water for their households. No wonder fear of wells is a slightly more feminine-coded fear.

- Tries to singe it with a candle

- Sings it lullabies

- Pours it a saucer of milk

- Shakes her fist at it — now we’re into the meltdown phase. Until this point, Cheli Duran Ryan has made use of beautiful verbs and other descriptive words, but now the pacing speeds right up. It’s hardly worth point out that the pace of a story increases the nearer the character gets to the big battle phase of a story (or its standin). It feels so intuitive, right? Easy to forget that when you’re writing, though.

- Smokes it in the chimney

- Stomps on it

- Spanks it

- Digs a grave for it

- Finally, she spits at it. This is so shocking precisely because it’s not very feminine!

Notice how Hildilid basically has a toddler tantrum. Young readers really enjoy watching characters lose their temper. Some of the finest modern examples include Z Is For Moose by Kelly Bingham and Paul O. Zelinsky and Pig The Pug by Aaron Blabey.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

In a typically feminine myth, there is no show-down, no massive battle with a Minotaur opponent. Instead we have a main character who thinks her way through a problem, in this case a problem against nature.

The battle phase must be there, though, in any story. Otherwise the story will feel unfinished to its audience. In stories with no actual battle, there needs to be a proxy, and in this case it was emulated with Hildilid’s escalating anger.

In a battle scene, the main character comes close to death, literally or metaphorically. When Hildilid dug a grave ‘for it’, she was really coming close to a metaphorical death herself.

ANAGNORISIS

The reader realises all along that Hildilid will never stop the sun from setting. Any revelation is entirely on the part of Hildilid, the fictional intradiegetic character. So what does this story have to offer the reader? After all, aren’t stories ultimately designed to teach us something, however entertaining they may also be?

This isn’t a story about changing the course of the sun; it’s about dealing with anxieties. We realise that sometimes it’s impossible to change our environment, because aspects of our environment are beyond our control. Instead, we can only change our responses. This picture book is a mythic, picture book equivalent of the famous Serenity Prayer:

Father, give us courage to change what must be altered, serenity to accept what cannot be helped, and the insight to know the one from the other.

American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, 1932 or 1933

(Nieburhr’s words have since been changed to suit contemporary English speakers, but those were his original words.)

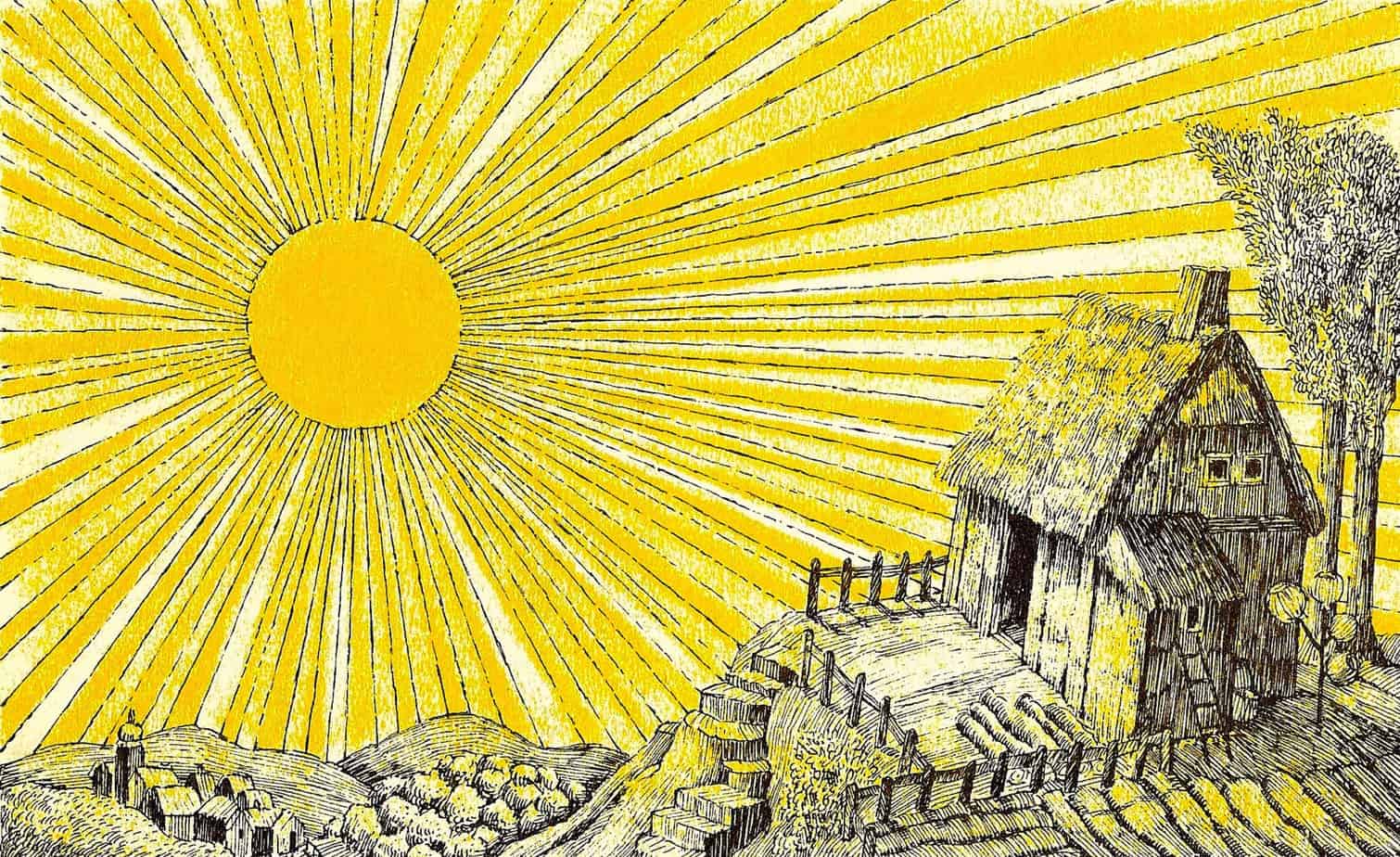

Why did Lobel choose to illustrate this story in black and white? Several reasons, I think. First, low light desaturates a landscape. Second, the reader turns the final page and is bowled over by an unexpected rush of colour, a picture book simulation of stepping out into the sunlight after a long nap.

In 1971, printing technologies were quite different. Today’s young readers are treated to far more sophisticated colour in their picture books. So it’s easy to underestimate how wonderful this page of yellow would have looked to young readers back in 1971.

For a modern example of a picture book ‘burst of colour’ on the final page, you can’t go past Tad by Benji Davies. Like this story of Hildilid, the narrative is simple, the colours muted. But then you get to the final spread and the colour absolutely pops.

NEW SITUATION

Hildilid’s world hasn’t changed even a little bit, but perhaps she has? This isn’t actually clear. It doesn’t matter because Hildilid is a take on the fairytale witch archetype and archetypes don’t tend to develop much as people.

The idea is that the reader will have changed.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Hildilid may learn that she can’t get rid of the night, or she may go through the same rigmarole every night, for all we know! She may be a female equivalent of Sisyphus, doing the same fruitless tasks all night. I’m sure a diagnosing psychologist applied the DSM to Hildilid they could come up with any number of diagnoses, but Hildilid’s way of dealing with fear by all those useless actions hews closely to how humans deal with anxiety. The trick is to do something useful with anxious energy, e.g. protest and send letters to politicians rather than getting high and staying in bed.

RESONANCE

Humans have always been afraid of the dark. We probably always will be. Picture books about this particular fear remain popular, and it amazes me how storytellers never run out of plots about dealing with fear of the night-time.

Stories about old women who live alone in the wilderness remain popular, too. She’s a take on the ‘silly peasant’. The modern pop-cultural version of this character is the Crazy Cat Lady.

FURTHER READING

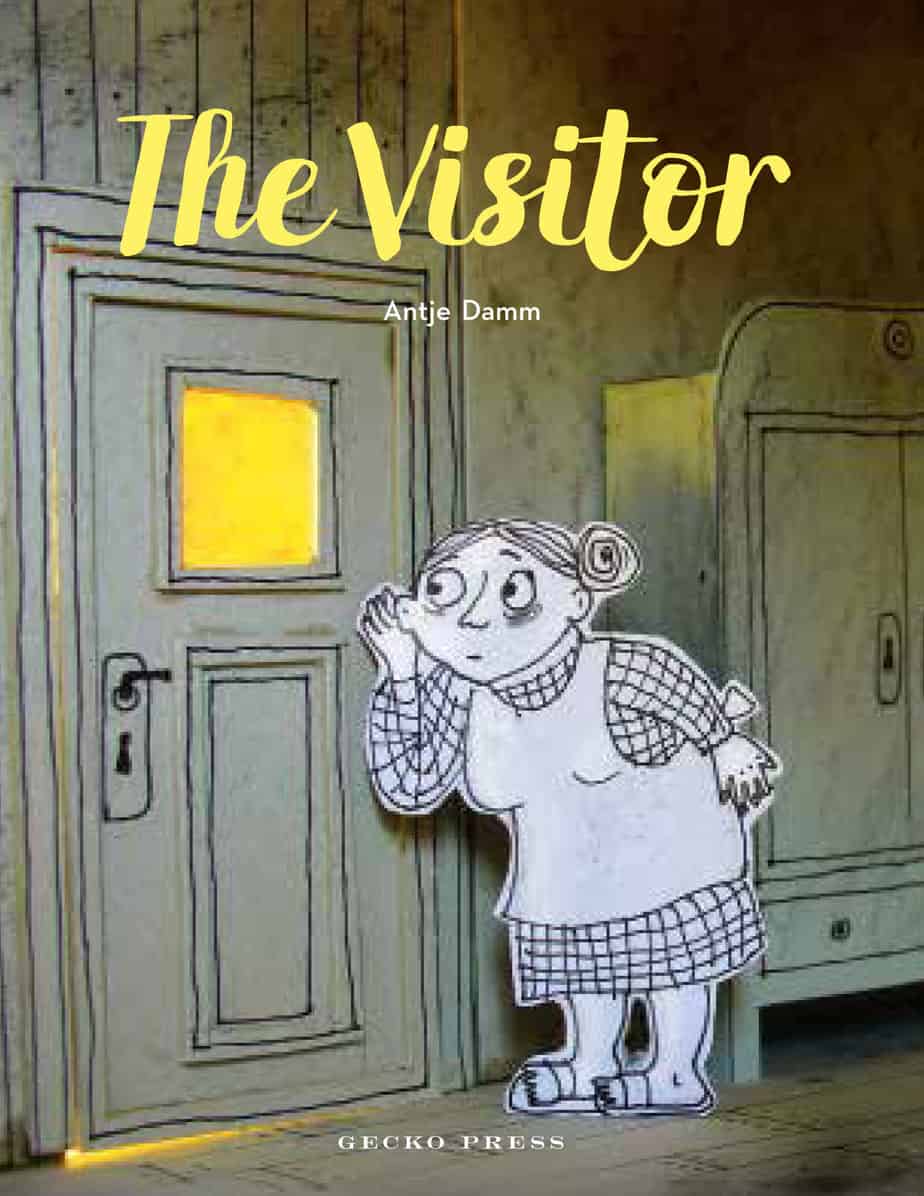

Elise was frightened—of spiders, people, even trees. So she never went out, night or day.

One day a strange thing flies in through the window and lands at her feet. And then there comes a knock at the door. Elise has a visitor who will change everything.

This is a gentle, sympathetic story about a child who unwittingly brings

light and colour—literally—into a lonely person’s life.