“Her First Ball” is a short story by Katherine Mansfield, written 1921. Though this story is nigh on 100 years old, it’s a tale of pick up artist culture, and reminds of the ‘toolies’ who attend Schoolies Week here in Australia.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “HER FIRST BALL”

Leila has turned 18, so must now attend balls in order to find a husband. Her city cousins, The Sheridans, introduce country-girl Leila to this exciting, dream-like world.

The story opens like this…

Exactly when the ball began Leila would have found it hard to say.

… which reminds me of a classic writer’s problem: Where does this story begin? This is a problem faced by anyone who’s ever recounted an incident. What was the inciting incident? Peter Selgin writes about that here.

Mansfield decides to open “Her First Ball” in the cab on the way to the ball, which Leila shares with her cousins Meg, Jose, Laura and Laurie. Later she’ll include a flashback to Leila’s anxiety, as she sits on the bed pleading with her mother not to go at all.

SHORTCOMING

Leila is at a social disadvantage because she lives in the country, and the fact that she lives in the country in itself speaks to a naivety below her years.

Another iconic New Zealand writer, Frank Sargeson, didn’t think much of this story. He didn’t accept the overarching shortcoming of Leila:

… the title by itself almost tells the story. A young country girl is staying with her town cousins who take her to a drill-hall ball. It is all very much indeed in the feminine tradition. Dresses, gloves, powder, flowers — and all the similes come tumbling out: A girl’s dark head pushes above her white fur like a flower through snow … little satin shoes chase each other like birds…. But later on we come to the point of the story. The girl, Leila, bewildered and enchanted by it all, is breathless with excitement. How heavily, how simply heavenly! she thinks. She dances with young men with glossy hair—and then with an older man who is both bald and fat. He perceive stat it is her first dance and tells her that he has been doing this sort of thing for thirty years. Then he goes on and pictures Leila herself in years to come. Her pretty arms will have turned into short fat ones, he says. And she will be sitting up on the stage with the chaperones while her daughter dances down below. And his words destroy her happiness. The music suddenly sounds sad. And she asks herself an agonising question: Why doesn’t happiness last forever? ‘Deep inside her’ we read, ‘a little girl threw her pinafore over her head and sobbed.’ And of course she hates the bald fat man.

Now I don’t know how my listeners will feel about this story, but for me it just doesn’t come off. It is, no doubt, tru e enough of many young girls, but for my part I’m afraid I can’t help making some comparisons. For instance, had any of Shakespeare’s young heroines (wonderful ones, say, like Perdita in The Winter’s Tale, or Marina in Pericles)—had they encountered that elderly bald fat man, and had he told them that shocking truth—well, I don’t know, but I fancy they would have just laughed and asked him why he wanted to say anything so obvious. In other words, young female character can be made of somewhat sterner stuff, and there is something in my make-up which refuses to accept the suggestion that that particular trying moment in the girl’s life was really so important and significant as it is intended to be.

Frank Sargeson, Conversation in a Train and Other Critical Writings

Sargeson seems to have forgotten the final paragraph of this story, in which Leila forgets all about it, but he taps into something that’s been a more recent conversation among bookish and film-loving types: Why do female characters always have to be so kick ass and confident? Lack of diversity among female characters is a big part of the problem with the phrase ‘strong female character’. Why do girls always have to be so damn strong? This is the problem boys have faced since forever… Is it girls’ turn now?

I can’t say I’ve had the exact experience Leila had. But I can give you two personal examples which resonate:

The first is from watching TV. Most of TV is forgettable, and the vast majority of TV dating show interactions are equally forgettable, but a few years ago I was watching that Chinese dating show on SBS when one bachelor rejected an interested young woman by telling her, “I can imagine what you’ll look like when you’re old.” She seemed taken aback and replied with something like, “I can see what you’ll look like when you’re old, too.”

I took a close look at this young woman and I really couldn’t see what he was seeing. Of all the insults hurled on that show, the accusation that she already, as a young woman in her prime, masked the shadows of ageing, seemed to me about the worst thing someone could say to another person in a dating context. (My take on it: She reminded him vaguely of someone he knows in real life who is actually old, and he blurted it out awkwardly.)

When I was in my mid-twenties, a guy who worked as an artist in the shed attached to my rented converted barn (long story) turned up one night when I was making a funny video starring my workmates. I was doing some last minute editing because I had to show it to my audience the following day. But I had run out of storage space on my laptop and I showed him what I was doing. He volunteered to pop down to the supermarket and pick up a spool of CDs.

First, I showed him what I was doing. I’d taken a video of my boss — an experienced, capable and very kind French teacher, who was speaking to her class at the time of filming, in what I assume was a fairly boring vocabulary exercise — one she’d done a thousand times. She wasn’t exactly animated. She sat hunched on her stool, with a look of middle-aged concentration.

I was the other languages teacher in our department, about 25 years younger than my head of department. Alistair next door was a young looking 39, but 39 nevertheless. Whereas women consider ourselves old around the time of our 30th birthday, he considered himself well-and-truly in his prime. “Oh. You’re hot,” he mused, looking at the video I’d made, “but I guess you’re gonna look like her one day. Such a damn shame.”

It’s worth pointing out, though Frank Sargeson was not your stereotypical privileged macho man owing to his being gay in an anti-gay era, he did not experience life as a woman, either. He wasn’t a product of a culture which tells young women that the most important thing about us is the beauty which comes only with healthy, fulsome youth, and that when our beauty is gone, there’ll be nothing at all left to replace it. (In fact, Frank was well-known for his lack of attention to aesthetics. His house was a hovel — he cared only about his vege patch.)

Having been on the receiving end of comments like that, I have more empathy for Leila than Frank did.

What about you?

DESIRE

By today’s standards, Laurie’s a little weird with his sister Laura, calling her ‘Darling’ and possessively telling her he’ll dance the usual two dances with her. Meanwhile, country-cousin Leila is noticing every detail, wanting to keep the rubbish tissue paper out of Laurie’s new gloves as keepsake.

Leila doesn’t know what to do, so she follows her cousins. Once at the ball, the girls go straight to the toilet/dressing area, where young women crowd around the mirror. This is exactly what it’s like:

And everybody was pressing forward trying to get at the little dressing-table and mirror at the far end.

I once wrote a short story in which this happens at a school ball, and a male critique partner expressed his skepticism, not believing that women’s toilets are like that at all. I’ve since concluded that “Her First Ball” is a particularly feminine story, more generally relatable to woman readers.

Mansfield herself sees the ridiculousness of the dressing room situation:

“How most extraordinary! I can’t see a single invisible hair-pin.”

OPPONENT

Meg introduces Leila to her friends in a rather condescending way, turning herself into a mother hen. The girls respond with etiquette but are obviously more interested in the men, standing on the other side of the room. The men are the romantic opposition, and one man in particular.

PLAN

Though Leila hasn’t got a clue what the formal proceedings are, the men all cross the parquet floor at once and fill up the girls’ dance cards. Failure to fill up a dance card felt like a serious rejection. The dance card culture lasted in New Zealand until about the 1950s, when dating started to become more informal. The wars changed culture a lot — women would have fun dancing with each other when there weren’t enough men to go round.

In 1921, the girls don’t have much say in who they get to dance with. If they don’t want to dance with someone, they’re unable to decline:

“Let me see, let me see!” And he was a long time comparing his programme, which looked black with names, with hers. It seemed to give him so much trouble that Leila was ashamed. “Oh, please don’t bother,” she said eagerly. But instead of replying the fat man wrote something, glanced at her again. “Do I remember this bright little face?” he said softly.

Because in this social milieu, it is men who do all of the choosing. It’s not up to Leila to make any plans. Instead she is swept along with the proceedings, on a treadmill (the first step on the moving walkway towards boring middle age). The ‘whirlpool’ sensation we get from Mansfield’s imagery, with ribbons flying and streamers and elongation describes most literally the sensation of being spun around during a dance, but it also symbolises being swept up into a culture of matrimony which begins with one’s first ball and ends with the women dressed in black (as the chaperones are — as a clear sign they’re not ‘on the market’ — but this is of course symbolic of death). By going to your first ball, you’re now on that inevitable decline. For Mansfield, beginnings are reminiscent of endings. She can’t enjoy a beginning without also thinking of its ending.

There’s a flashback to Leila’s boarding school, where she learned to dance but under completely different conditions — staid and without the sexual tension Leila had not anticipated.

In the brief moment where her designated partner doesn’t come to collect her, Leila thinks melodramatically that she’s going to ‘die’. But then he does come and they make small talk as they dance. This hooks into the ‘treadmill towards death’ idea.

The second dance partner also opens with a comment on the floor. Leila wonders if this is customary. Like the previous one, this young man asks if Leila had attended a certain party the week before. The conversation with the second young man is revealed to be exactly the same as that with the first. This is significant. The night now has a fatalistic feel to it — as if everything is playing out according to some supernatural rulebook — the characters might be automatons, and there’s something creepy about robotic behaviour. (That’s why they’re used so often in horror.) Within the world of the story, these boys attend many balls, saying basically the same thing to most of the girls, and are bored by it. This juxtaposes with Leila’s excitement at the novelty, serving to emphasise it. (This boy takes her to eat an ‘ice’ — a novelty people had fridges and freezers in their homes. Such products had to be delivered right before they were consumed.)

Now that Leila has experienced two identical interactions, she’s expecting the same again. So are we, due to the Rule of Three in Storytelling, but at the same time, we know our expectation of sameness will be subverted.

BIG STRUGGLE

Leila’s third dance does not go as the first two did. The old fat man turns out to be even older than she thought.

As reader, I am annoyed with this man. What the hell is he doing, inserting himself into a social event designed for young people? He reminds me of the 29-year-old men who insist on attending Schoolies Week year after year after year. (Here in Australia these men, mostly men, often in their 40s, are known as ‘Toolies’.)

This guy seems to get off on shit-talking to young women — the younger and more naive she seems, the more he enjoys it. These days there’s a word for it: Negging. In its most basic form, a man insults a woman hoping to elicit a strong reaction, because a strong reaction is — for him — better than no reaction. He then has something to ‘work with’, and his next task is to simply flip that negative strong emotion into a positive one, which according to pick up artists, actually sometimes works.

Because Leila has been culturally conditioned to be nice to men, she looks at his bald head and feels ‘quite sorry for him’.

Sensing this, the middle-aged man negs Leila by pointing out that the rules are different for women, who must modify their behaviour as they hit middle age, unlike himself, who continues to dance, since he feels like it:

“Of course,” he said, “you can’t hope to last anything like as long as that. No-o,” said the fat man, “long before that you’ll be sitting up there on the stage, looking on, in your nice black velvet. And these pretty arms will have turned into little short fat ones, and you’ll beat time with such a different kind of fan—a black bony one.” The fat man seemed to shudder. “And you’ll smile away like the poor old dears up there, and point to your daughter, and tell the elderly lady next to you how some dreadful man tried to kiss her at the club ball. And your heart will ache, ache.”

The middle-aged man has been doing this for so long, he knows the exact kind of scripted small talk Leila has already been exposed to. He mentions the floor, but points out her feelings will have changed towards it, almost as if he’d been listening intently to Leila’s first two conversations:

And you’ll say how unpleasant these polished floors are to walk on, how dangerous they are. Eh, Mademoiselle Twinkletoes?” said the fat man softly.

The man’s omniscience almost turns him into a kind of evil fairy godfather — a ghostly figure whose only purpose at the ball is to ruin Leila’s night.

I’m also reminded of a scene from The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro. The first person main character, a faithful butler, embarks upon a mythic journey and encounters a fellow traveller.

“I’m telling you sir, you’ll be sorry if you don’t take a walk up there. And you never know. A couple more years and it might be too late” — he gave a rather vulgar laugh — “Better go on up while you still can.”

It occurs to me now that the man might just possibly have meant this in a humorous sort of way; that is to say, he intended it as a bantering remark. But this morning, I must say, I found it quite offensive and it may well have been the urge to demonstrate just how foolish his insinuation had been that caused me to set off up the footpath.

Remains of the Day

No one appreciates anyone else reminding them of how old they’re getting, no matter how young they are at the time. It strikes me that women absorb the message that they are getting too old too fast before men feel it. (This has been studied. Women first start to feel old at the age of 29, men at 58.

ANAGNORISIS

Leila takes him at his word, and laments:

Oh, how quickly things changed! Why didn’t happiness last for ever? For ever wasn’t a bit too long.

Leila has had one of those epiphanies like Sun of “Sun and Moon”, in which the much younger Sun also realises that perfect evenings can never last forever.

Leila continues to smile, because that’s what you’re required to do at a designated ‘happy’ occasion, but her feelings on the inside are quite different:

But deep inside her a little girl threw her pinafore over her head and sobbed. Why had he spoiled it all?

Then the middle-aged man pulls out a classic pick up artist (and also a classic schoolyard bullying) technique — he tells, “you mustn’t take me seriously, little lady.” He was just joking, see! JOKES!

If Leila took him seriously it’s all on her! Why can’t young ladies grow a sense of humour? Sheesh.

NEW SITUATION

The ending is similar to that of “The Doll’s House“, in which the underdog girl has something horrible happen to her, but almost with determination, she’s resolved not to let it bother her. Like Else Kelvey, Leila forgets all about her dance with the horrible, middle-aged man, but the reader knows that even if she’s ‘forgotten’ the incident, the epiphany remains with her.

I expect one day, when Leila sits up on the stage watching her daughter, she will recall her first dance and she will recall that man.

What do you make of endings in which the character ‘forgets’ the bad thing and moves on?

We now know that the brain can go back in time and change how an event is perceived. Psychologists call it ‘postdiction’ (riffing on PREdiction). There is also a Latin term for it: vaticinium ex eventu (foretelling after the event).

This is probably an adaptation to help us get on in life after horrible things happen.

FURTHER READING

“In-flight Entertainment” by Helen Simpson is a much more modern story but the underlying structure is the same.

I use the same epiphany sequence in “Midnight Feast“. Roya sees the impact of climate change when she finally takes a peek out of her own kitchen window, but she’s unable to sleep until she forgets she’s ever seen it.

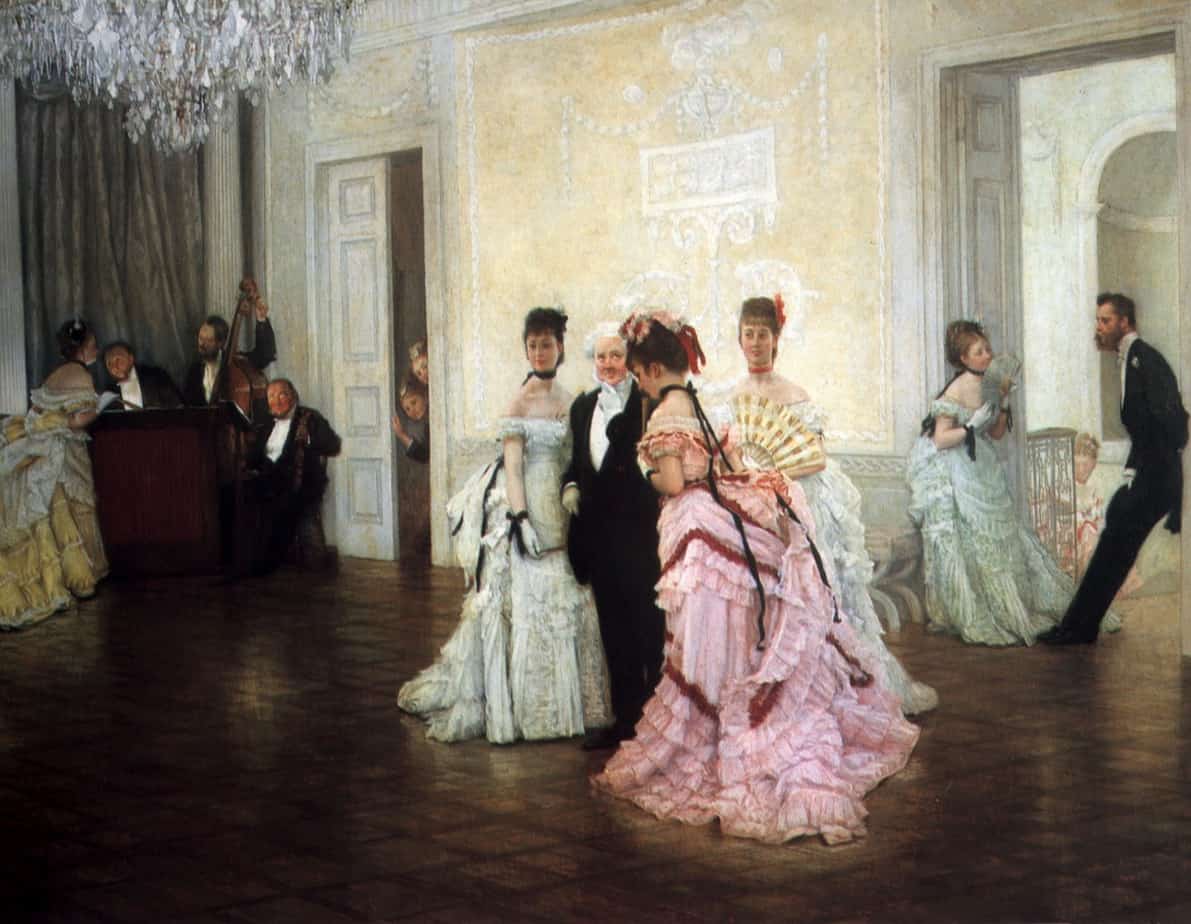

Header painting: Louis Haghe – The Ballroom, Buckingham Palace, 17 June 1856