**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

“Heirs of the Living Body” is the second story in Lives of Girls and Women (1971), sometimes considered a novel, sometimes a collection of short stories. Each of these stories can be read in isolation, but all concern the life of a woman called Del Jordan growing up in the small fictional Ontario town of Jubilee.

This story is about Del learning to live with the reality of death, and how her personhood has been shaped first by her ancestry, then culturally by extended relatives.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “HEIRS OF THE LIVING BODY”

GRUMPY UNCLE CRAIG

Del Jordan (still unnamed) tells the story of her extended family, starting with a character sketch of her Uncle Craig, who worked as clerk of the Fairmile Township. He lives with his younger sisters, Auntie Grace and Aunt Elspeth at the family house on Jenkin’s Bend, named after a young man called Jenkins who was killed by a falling tree.

Uncle Craig’s main occupation in retirement was writing a history of the local area and compiling the family tree. Grace and Aunt treated this task as very important because their big brother had become the man of the house, but in fact Craig was a fastidious compiler and, regarding the family history, only got so far as 1909.

THE SPINSTER AUNTS

In contrast to the designated family historian they rally around and support, these elderly spinster aunts know a lot about more recent family and town history. But their knowledge isn’t the kind that make it into the history books. Theirs is the feminine knowledge of gossip and shared stories, rehearsed many times in their tellings and retellings. In Del’s presence the aunts recount tales such as an uncomfortably racist incident (to modern readers) in which Elspeth dressed up as a ‘darky’ and scared an Austrian farm hand their father had employed by creeping up on him. The sisters unironically observe that their parents didn’t trust foreigners, without understanding that by dressing specifically as a Black man to give the Austrian foreigner a scare, they reveal their own deep mistrust of ‘foreigners’.

The aunts recount several other practical jokes from their youth. Del observes that the aunts are most at home while milking cows, where they compete with each other by comedically trying to out-sing each other, each belting out a different song. These old biddies may be fun, but they also reserve a competitive, nasty side for their niece, which only reveals itself when Del’s mother is out of earshot.

Kareem Khubchandani talks about aunties, figures across culture that stand for inquiry and succor, at limits of, or outside traditional family structures. The conversation spans genres and contexts, mainly focusing on work in the new field of Critical Aunty Studies.

High Theory Podcast

SUMMER HOLIDAY WITH THE SPINSTER AUNTS

As a girl, Del spends summer holiday at the Jenkins Bend house, in the company of her aunts. There, she learns about another, multi-layered, foreign way of communicating. Whereas Del’s own mother is straight-forward, with the aunts Del must watch what she says and how she says it, lest evil subtexts are assumed. The mother has managed to offend the aunties (her sisters-in-law) many times, and Del feels the aunties don’t like herself much either. Presumably, they don’t like Del because they don’t like Del’s mother.

THE SHOCK OF TWO-FACED HOSPITALITY

One summer, Del is staying with the aunties at Jenkin’s Bend when the aunties’ rural neighbours make a house call to introduce their new son-in-law, who they are very proud of. He is a lawyer. Del is perturbed to witness how her aunties mock the young man after he has left. Del puts this down to the family’s Irish heritage, which involves a ‘gift for rampaging mockery, embroidered with deference’.

COUSIN MARY AGNES

There’s another (favoured, overtly preferred) niece who visits the aunties at the same time — older than Del, slightly brain-damaged during birth and a bit of a bully. Del can’t stand her. But Del does acknowledge her cousin’s humanity, which the adults can’t seem to do. Their feelings for poor Mary Agnes stop at feeling sorry for the girl, whereas Del can see the older cousin has a secret, private side. Complicating Del’s feelings, Mary Agnes was gang-raped by a pack of teenage boys, was subsequently left naked in a field, and almost died of bronchitis, to which she is prone. Del can’t help feeling that the ‘main’ shame of this event was the nakedness. (As readers are, Del is left to fill in the gaps about what the boys did to her. Such details are unmentionable.)

THE DEAD COW

One day during play the two cousins happen across a dead cow. Del is fascinated by the deadness of it. Mary Agnes tells Del to stay away, but when Del dares Mary Agnes to touch the dead cow, she does. Now she’s tainted by its deadness and Del feels afraid. This story is about Del’s discomfort with death. She feels discomfort around Mary Agnes’ mother, who struggled to conceive and give birth to Mary Agnes, and is now forever tainted by the reality of her womanly birthing parts. Del feels her aunt’s childbearing parts are too closely connected to death.

Alice Munro shows us another instance of discomfort with female body parts in a brief description of an off-the-page character who was tainted by dint of being the daughter of a gynecologist. Check out my analysis of “Labor Day Dinner“.

“Heirs of the Living Body”, to my mind, is a classic literary example of Fear of Engulfment, depicted clearly in a fairy tale such as “The Frog Princess“. The cow is a feminine-coded animal (with obvious mammary appendages) and so a dead cow links femininity, birth and death in a way that’s not immediately legible to young Del.

UNCLE CRAIG IS DEAD

These memories of Del’s uncle, aunties and cousin open the story.

Fast forward to when Del is a slightly older child. Del’s mother announces over breakfast that “Uncle Craig died last night” and that Del will be required at the funeral. Del doesn’t want to go. Younger brother Owen is excused as he is considered too young.

Alice Munro has previously explored the ways in which girls are required to grow up more quickly than boys. Sure, Owen is younger, but Munro’s earlier stories such as “Postcard” and “The Time of Death” suggest that, had Owen been a daughter, he’d have been required to put on a black dress and be polite at the funeral anyway.

DISASTER AT THE FUNERAL

At the funeral, Del disgraces herself and possibly stigmatises herself forever. When Mary Agnes insists the pair of them go look at the old man’s dead body, this time (unlike with the cow) Del resists. She can’t bear to situate herself anywhere near death. She can’t contemplate it, has not yet come to terms with the birth-death cycle which comes for us all.

But Mary Agnes is strong, and Del panics. Del bites her cousin’s arm and draws blood. Del has failed at young womanhood. The girl’s gone wild, briefly rejecting the expectations of meek femininity.

The aunts are good for comic relief and wonder if Del has rabies. This is Alice Munro making a further connection between human and (farm) animal, reminding us all that humans are a type of animal.

Del’s mother apologises for her daughter and regrets bringing the young girl to something she clearly isn’t ready for.

THE AUNTS DESCEND UPON JUBILEE

Unexpectedly, the aunts decide to move to Jubilee, ostensibly to be of use to Del’s father on the fox farm. They’re too old to be of much practical use, but Del’s father takes them socks to darn. These two old women are strangely useless without a man to fuss over. Uncle Craig was the figure who gave them purpose. Del’s own father intuits this absence and makes sure to give them something to do for him.

UNCLE CRAIG’S LONG, BORING MANUSCRIPT

When Del is few years older, and has proved herself very capable at school, the aunts give her something very important: The 1000 page historical tome left unfinished by Uncle Craig which, they assure her, is a work of brilliance. They want Del to read it over and over, absorb the style, and finish as Uncle Craig’s living ghost writer.

Alice Munro provides us with a page of his writing. It is dense and boring. No one would want to read 1000 pages of this guff, even if they did take an interest in the subject matter.

THE INSULT OF BECOMING A WOMAN

Del takes the manuscript home and puts it under her bed, but realises this would be a good place to hide her own writing. It is now that readers learn Del has writing aspirations of her own. It is a massive insult for the aunts not to see potential in their niece. Readers can deduce that, had Del been a boy, these elderly aunts would take her academic life seriously. They would nurture Del’s own voice. But no, they ask for Del’s own voice to be subsumed to the dull, dry voice of the dead brother.

So Del continues to keep this writing part of herself private. She doesn’t want her own writing (her own self) contaminated by the constant reminder that she cannot even expect to have her own pursuits taken seriously. She stores Uncle Craig’s tome in the basement, a part of the house which symbolises the dark subconscious.

WHOOPS, A FLOOD

A few years later, when Del is at college, the Jubilee basement floods. The story ends with Del’s ambivalent feelings about her dead uncle’s soaked and useless book of local history: She feels remorse and also a ‘brutal, unblemished satisfaction’.

Given that Alice Munro is herself a writer, herself a woman, herself from a family who thought reading was almost sinful, especially in a woman, it’s difficult not to imagine Del’s ambivalence derives from the writer’s own life experience, and the frustrating reality that women’s work is considered less valuable than the same work performed by men.

Comically, ironically, it was the two-faced aunts who taught young Del to recognise and acknowledge two conflicting emotions happening concurrently within herself.

THEME: DEATH, CARNALITY, FAMILY INHERITANCE

Throughout “Heirs of the Living Body” we follow the thread of death and carnality: the dead cow, the bite on the cousin’s hairy arm, an aunt’s varicose veins and birth canal imagined as a blood-filled man-made river. We are left with the feeling that Del is the product of all ancestry which has come before her. She cannot escape her meaty, slightly shameful body. There’s no escaping the influence of family, or the culture that shaped them/us all.

Del’s mother alerted readers to this theme by talking about organ transplants as she and Del prepared for Uncle Craig’s funeral. The mother wonders if there really is any such thing as death. These days, a person can be kept alive by someone else’s organs. She had been reading about transplants in an article. This 1970s short story takes its name from the fictional article: “Heirs of the Living Body”.

If “Heirs of the Living Body” were written today, I wonder if Del’s mother might instead have been reading about epigenetics.

Epigenetics is the study of how your behaviors and environment can cause changes that affect the way your genes work. Unlike genetic changes, epigenetic changes are reversible and do not change your DNA sequence, but they can change how your body reads a DNA sequence.

CDC.gov

THE GENDER HIERARCHY

For as long as there has been social hierarchy, those lower down have been dealing with their situation using a variety of coping mechanisms. One is humour, often via satire.

Alice Munro illuminates the gender hierarchy at the level of the family with a beautiful description of how her burlesque witch aunts both respect the man of the house while at the same time making fun of him.

They respect Uncle Craig by giving him time to pursue what he calls work but what is actually a fruitless passion. Compare and contrast this description to “The Office” in Dance of the Happy Shades, in which the woman narrator cannot for love or money get anyone to take her writing “hobby” seriously. In contrast, a man needn’t go to the trouble of renting an office; the women at home will rally around him, take care of his every bodily need no matter how frivolous his passion, how spindly his talent.

THE CONTEMPORARY EQUIVALENT OF THIS

This gendered dynamic reminds me of a line from an advertisement for the Amazon Echo which follows a day in the life of an insufferable white family as they unbox and start using their new device. The advertisement so uncomfortably straddles the line between parody and taking itself seriously that the Internet wasn’t sure what to make of it. It has been parodied many times, with voiceovers and various meme versions across YouTube. The first time I saw it, I was far more taken in by what am I even looking at than by the Amazon Echo itself, or even by the parody I thought I was watching. I couldn’t work out if the ad itself were a parody.

What has this to do with Alice Munro’s “Heirs of the Living Body”?

I’m pointing out that the dynamic shown in Munro’s 1970s story is alive and well. In the Amazon ad, The Man of the House struts around importantly while his wife nods and rolls her eyes at him. Isn’t Dad a dork! Yet still, he is clearly the Man of the House. It is the father who has spearheaded the expensive new purchase. It is the father who takes it upon himself to explain to everyone else what it does. His son roasts him (“You just read that off the box, huh”). After mimicking him behind his back, his wife later rejects him for intimacy in a supremely heteronormative display of marital stereotyping. She also asks Alexa to add wrapping paper to the shopping list. She does the family cooking. Meanwhile, the father has gotten the day of the week wrong, thinking it’s Saturday when it’s actually Thursday. Doofus Dad set-up is complete.

Yet also in the ad, Man of the House struts in from outside, suggesting he has been at work earning the family income. It is the father who asks for the “flash new briefing”, because presumably it is important for the father to know the news, whereas the wife keeps sleeping. When your job is wrapping presents and making dough (literal dough), the world news just isn’t really important to you, is it.

This guy’s status as Man of the House is unassailable. In fact, if he weren’t depicted as Man of the House, the “jokes” wouldn’t work. The vibe would be different; this would look a lot like bullying.

And so the modern cosy version of conservative heterosexual households looks like this: The father is still in charge, but the gendered hierarchy is made imperceptibly subtle and palatable by turning him into a figure of fun. This dynamic gives rise to irritating aphorisms such as “Happy wife, happy life” and “My wife makes all the decisions, I just earn the money.”

Munro does a great job of showing the different strains of hierarchy within her family. While Uncle Craig is a cranky old git, Del doesn’t care about his opinion of her in the way she cares about the opinions of the women. ‘Masculine self-centredness made him restful to be with.’ To be clear, I don’t interpret this as some kind of complementarianism — a theological view of gender in which men and women are said to be ‘equal but different’. Del understands there’s a hierarchy. This story concerns Del learning to live with that, and to make peace with her vital bodily importance in the birth-life cycle. After all, only (some, cis) women (between certain ages) can give birth. Her meatiness is her main human attribute in this system. Absolutely everything else comes way down the list, and the women of her family are complicit, having long ago absorbed the messages, having long ago learnt how to deal with the state of things via humour, playfulness and mild mockery.

MORE ON THE DEAD COW SCENE

The following tidbit about Munro’s childhood sticks out as important to “Heirs of the Living Body”:

One of the most popular games amongst Alice Munro’s friends at elementary school was “funerals,” where one person got to be the corpse and the others would stage a mock funeral, complete with “flowers” (weeds) and a tearful viewing

90 Things To Know About Master Short Story Writer Alice Munro

Here’s young Del Jordan, grimly fascinated by a dead cow:

I took a stick and tapped the hide. The flies rose, circled, dropped back. I could see that the cow’s hide was a map. The brown could be the ocean, the white the floating continents.

“Heirs of the Living Body” by Alice Munro

Del continues to examine the dead cow closely:

Being dead, it invited desecration. I wanted to poke it, trample it, pee on it, anything to punish it, to show what contempt I had for its being dead. Beat it up, break it up, spit on it, tear it, throw it away! But still it had power, lying with a gleaming strange map on its back, its straining neck, the smooth eye. I had never once looked at a cow alive and thought what I thought now; why should there be a cow? Why should the white spots be shaped just the way they were, and never again, not on any cow or creature, shaped in exactly the same way? Tracing the outline of a continent again, digging the stick in, trying to make a definite line, I paid attention to its shape as I would sometimes pay attention to the shape of real continents or islands on real maps, as if the shape itself were a revelation beyond words, and I would be able to make sense of it, if I tried hard enough, and had time.

“Heirs of the Living Body” by Alice Munro

CHILDREN LEARNING ABOUT DEATH

Fascination over a dead animal or insect is a common childhood experience. You probably have a memory or two yourself.

Yesterday 6yo was thrilled to find a stock that she’d buried in the snow weeks ago. She brought it inside, painted parts of it and gave it a name. This morning she accidentally snapped it.

She and 8yo have organized a memorial service for 9:30.

Ted McCormick on Twitter @mccormick_ted, March 6, 2021

Every single time I see a take that amounts to “if you write about X happening, or like fiction where X happens, you like X” I’m reminded of this one time I was at a casual friends house as a young kid. We were in her room, pretending to “be orphans” escaping from an evil orphanage and having to take care of each other and fend for ourselves. It was all very Little Orphan Annie/All Dogs Go to Heaven and based on the 80s pop media.

And this girl’s mom comes in, hears what we’re playing and gets all MAD and UPSET. She says that if we play act something, it’s because we want it to happen. So her daughter must WANT HER TO DIE.

First off lady, we were 6-year-olds, so take it down several notches. We barely had a concept of mortality for fucks sake. She made us feel so guilty and ashamed, because she was taking our game personally.

Now I have a 5 year old. And sometimes she looks at me and says “pretend you’re dead, and I have to -” Whatever it is. Some adult task she’s assigned herself.

And it’s just so transparently obvious that she’s practicing the idea of having to do things on her own. Which is exactly what 5-year-olds are supposed to do. I actually find it very flattering that the only way she can envision me not being available to help her is to be literally deceased. Otherwise, obviously, she wouldn’t have to do scary hard things alone.

It’s a natural coping mechanism. She’s self-soothing about what would happen if I wasn’t there by play-acting independence in a perfectly safe environment. She’s also practicing skills she needs, and making up excuses for practicing them on her own, without taking on the responsibility of being able to do them by herself all the time yet.

Humans mentally rehearse bad this in their brains all the time. We can do that by ruminating- going over worries over and over again, which tends to lead to anxiety and helplessness and depression. Or we can do it with a sense of play- by recognizing that the fiction is fiction and we can dip our toe into these experiences and expose ourselves to bad things without actually being injured.

My daughter does not want me dead. And I don’t want bad things to happen in real life. But fiction and pretend help me face the horrors of the world and think about them without collapsing or messing myself up mentally.

leebrontide on Tumblr

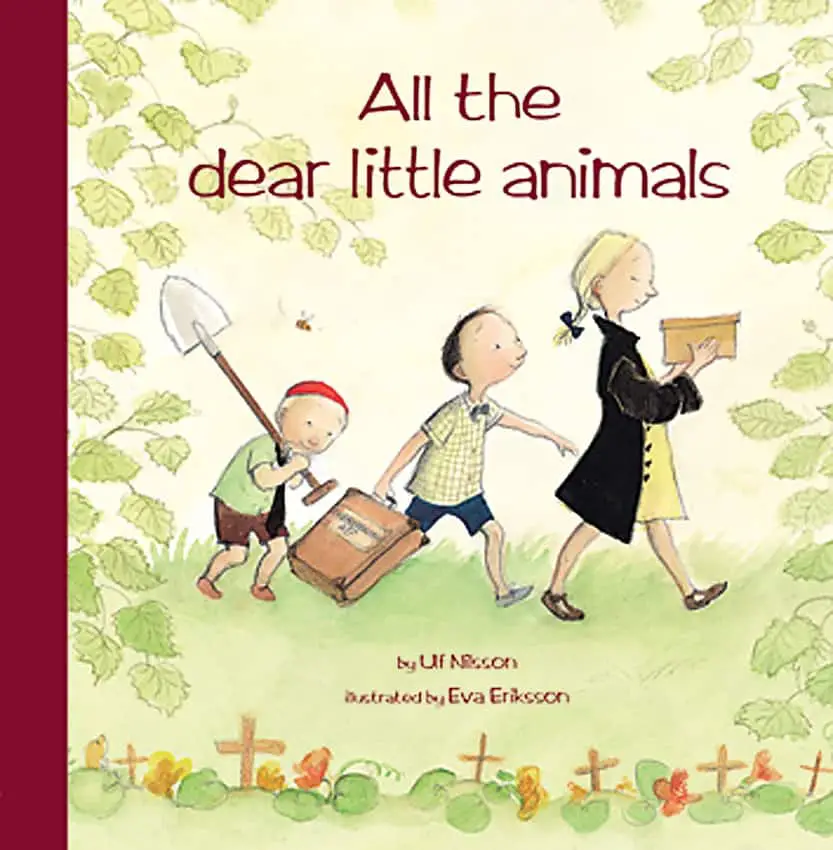

The very common experience of holding memorials and funerals for dead creatures is explored in a short, illustrated Swedish chapter book, translated by New Zealand’s Gecko Press into English: ALL THE DEAR LITTLE ANIMALS by Ulf Nilsson and Eva Eriksson. I believe there’s a reason this story wasn’t created or translated in America. Generally speaking, Europe has a higher tolerance for difficult themes in stories for young children.

The English language marketing copy of this picture book is more careful than I’ve seen previously:

This is a picture book for children aged five and up, and covers a difficult subject in an unsentimental way. It describes exactly the way children resolve big issues — through play.

I believe this caution — ‘for children five and up’, ‘difficult subject’ is aimed at American book buyers. America seems to have a different attitude regarding what’s appropriate subject matter for kids. Australia and New Zealand fall somewhere in the middle. In fact, the English version of this book was brought to us by New Zealand’s Gecko Press

This wonderful children’s book has since been turned into a short animated film:

Note how sweet and cute these stories are, of children giving animals funerals, valuing every life.

There’s none of that sweetness in Alice Munro’s description of Del with the cow. Del’s actions evince a grim fascination, followed by a fear of contamination. Contamination of the cow maps onto the stigma girls can so easily and dangerously garner, be it via a tragic gang rape or by biting a cousin at a funeral.

Notice how ‘fear of contamination’ prefigures the stigma Del experiences after biting Mary Agnes at the funeral. Notice how Alice Munro draws a straight line between the two events at both a plot level and a thematic, emotional level: Mary Agnes assumes Del wants to see the dead uncle because Del was previously fascinated by the dead cow. Mary Agnes feels stigmatised after biting Mary Agnes because she has revealed herself as a wild, dangerous creature. Ironically, she was trying to avoid the taint of death by refusing to set eyes on her uncle’s corpse. But there’s no escaping stigma and taint. People will create their own stories about you, sometimes based on very little.

THE DEATH OF ASPIRATION

As is usual in stories about carnal death, “Heirs of the Living Body” shows readers how something in Del has died spiritually, or else is in grave danger of dying: her literary aspiration. Another female cousin was smart enough to go to college but ultimately didn’t go. This working class family doesn’t want any of its members to get ideas above their station. In recounting this first person narrative, Del shows that she recognises in herself how she has absorbed this attitude.

Aspiration, like respiration, is as vital to life. Let’s take a look at the medical definition of ‘aspiration’ (which is not the meaning I used above):

Aspiration means to draw in or out using a sucking motion. It has two meanings:

Medline Plus

- Breathing in a foreign object (for example, sucking food into the airway).

- A medical procedure that removes something from an area of the body. These substances can be air, body fluids, or bone fragments. An example is removing ascites fluid from the belly area.

In this home environment, Del is in danger of breathing in the ‘wrong foreign objects’.

Fellow readers from working class families will understand this to the core. My own family is similar to this one except for the Canadian aspect. I am the New Zealand equivalent one generation younger than Del — a descendent of Irish Protestants and Scotch Presbyterians who emigrated to New Zealand and kept marrying other very similar families across five generations before I came along, with the odd Catholic mixing things up (i.e. my father).

Unlike my ancestors though, I was born into a relatively socialist New Zealand generation in which a university education was achievable and unremarkable even for working class kids, many of whom would be the first of their family to graduate.

But in keeping with my solidly working class roots, a day spent on the books, sitting round in lecture theatres wasn’t considered a real job. So alongside my full-time academic load, I did work my way through university as a cleaner (and also as a weekend retail assistant). At my weekday morning cleaning gig I cleaned in the same building as my own father, who in fact got me the job through the working class equivalent of nepotism. Not that I knew a single other student who was gagging for the job. The hours weren’t exactly… conducive.

From Monday to Friday we rose at 3:30 a.m. We cleaned lecture theatres and offices until 7 a.m., then I would spend the rest of the day at university (sometimes hearing lectures in the very theatres I’d vacuumed and wiped down earlier that day). Meanwhile, my father would spend a fractured day at other various cleaning jobs.

One day I noticed a cleaning job needed doing and no one was doing it. This was the hard work of mopping stairs, best suited to someone in their prime. Frankly, none of my older co-workers were putting up their hands. So I suggested to our boss that I stay on for an extra half hour per morning to get it done. This would earn me an extra five dollars per shift, before tax.

When I told my solidly working class father what I’d arranged for myself, he was shockingly unimpressed. In hushed tones, he told me I’d been cheeky to ask.

With the benefit of middle-age, I can see how formative my father’s reactions were. (I can give numerous similar examples.) Other fathers with more entitlement — fathers of my friends — would not have responded in that way. Other fathers — middle class and professional fathers — would have praised their young adult offspring for such entrepreneurial spirit and hard work, perhaps even expressing concern that this would leave even less time for the intensity of a full-time academic load.

We don’t think much of Entitled People but a complete absence of entitlement equals toxic servitude. If you know it, you know it. It is highly heritable and painfully recognisable to me in the extended family of Del Jordan. Alice Munro depicts it expertly in “Heirs of the Living Body”. It hurts to see Del hide her writing away in the box under her bed.