If you were put in charge of editing a collection called The Oxford Book Of American Short Stories, and you were American, wouldn’t you include one of your own? Actually, I have no idea if Joyce Carol Oates put forward one of her own stories for inclusion, or if she was chosen as editor after it had been decided by others that one of hers would be included. In any case, you will find “Heat” by Joyce Carol Oates in the aforementioned 1992 collection, edited by Joyce Carol Oates.

“Heat” was originally published 1991 in The Ontario Review. Funnily enough, you’ll also find this story in Heat and Other Stories by Joyce Carol Oates.

Content note for violence.

“HEAT” BY JOYCE CAROL OATES IN A NUTSHELL

The narrator looks back to her own youth, and remembers the murder of two sparky eleven-year-old twin girls called Rhea and Rhoda Kunkel. This story is not a murder mystery because the killer is soon located. Skipping trial, he is sent straight to a mental institution, where he stays for life.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS FOR “HEAT” BY JOYCE CAROL OATES

- The midsummer setting of “Heat” is integral to the theme of this short story. In what way?

- Joyce Carol Oates uses a slightly unusual (though not rare and not new) choice of narrative technique. Say what you can about this.

- The story is divided into two main parts: The narrator’s childhood focusing on the murder of the twin girls, then ends with a snapshot from the author’s adult life, in which she engaged in an extramarital affair. What have these two lifetime events to do with each other, so that they would appear in the same story? Do you find yourself comparing the events, juxtaposing them, or both? To what extent?

- What do you make of the characterisation of the murderer? How might readers armchair diagnose him today?

- Oates emphasises the sameness of the identical twins. There are other examples of ‘sameness’ running as a connective thread across the story. What are the other ‘samenesses’ and what effect do they achieve?

- In the Oxford introduction to this story, readers are told upfront what the author was trying to achieve: “For the author, the formal challenge of “Heat” was to prevent a narrative in a seemingly acausal manner, analogous to the playing of a piano sans pedal; as if each paragraph, or chord, were separate from the rest. For how otherwise can we speak of the unspeakable, except through the prism of technique?” What do you think Oates means by this, and do you think the story achieves its stated aim?

SETTING OF “HEAT”

PERIOD

I can’t pinpoint the year of this story specifically, but I believe the author wrote “Heat” while imagining her own adolescence. Since Oates was born in 1939, that places the earlier part of the story around 1950.

DURATION

The first part of “Heat” takes place over a few years, and so does the much briefer (on the page) second part of the story, in which we meet the narrator as an adult as she confesses something to us.

LOCATION

Smalltown America. (Americans will be better placed than I am to specify where this is set.)

Joyce Carol Oates was herself born in Lockport, New York. She grew up on her parents’ farm, just outside the town. (I find it interesting that Canadian author Alice Munro also grew up just outside a small [Ontario] town.)

If small towns are dangerous, being just outside a small town is the most dangerous — the most liminal — place of all.

ARENA

The entire story takes place in this small town, focalising on its periphery — geographically as well as socially. These twins as well as the murderer are outsiders. Notably, the murderers relatives end up leaving town and scatter themselves further away in the surrounding countryside.

MANMADE SPACES

The main street, the ice-cream store, the school, the Methodist church with its graveyard in a field out back.

NATURAL SETTINGS

We get the sense that nature is all around.

WEATHER

Beginning with the title, the story opens with a description of oppressive, midsummer heat.

It was midsummer, the heat rippling above the macadam roads, cicadas screaming out of the trees, and the sky like pewter, glaring.

The days were the same day, like the shallow mud-brown river moving always in the same direction but so low you couldn’t see it. Except for Sunday: church in the morning, then the fate Sunday newspaper, the color comics, and newsprint on your fingers.

opening to “Heat” by Joyce Carol Oates

Macadam is a type of road construction … in which crushed stone is placed in shallow, convex layers and compacted thoroughly.

Wikipedia

Note that midsummer can be utilised to convey happy times, but is just as often inverted. For more on this, see The Symbolism of Seasons in Storytelling.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

The twins ride rusty bicycles. The father has replaced the tyres (for safety) but not the kickstands (a convenience). The twins always lie those bicycles down in the same direction, and the pedal is always left at approximately the same place.

Throughout the story, Oates emphasises the oneness of the twins, and the position of the pedal is an eerie detail which almost elevates the girls to the supernatural. This is how children think of identical twins. As children, many of us imagined what it might be like to have an in-built best friend. Children’s literature is full of twins, and we tend to romanticise them. For example, the narrator of this story would have grown up reading The Bobbsey Twins, a franchise which ran from 1904 to 1979, written by numerous authors but all published under the name of Laura Lee Hope.

The ‘oneness’ of the twins can be seen in other ways: All of the summer days are ‘the same day’. (Joyce doesn’t use a simile — she tells us the days are the same.)

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

Because the entire story focuses on a childhood experience living in this one small American town, we don’t hear about outside events. For the girl narrator, only the town exists. The murders occupy all of her attention.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “HEAT”

NARRATION

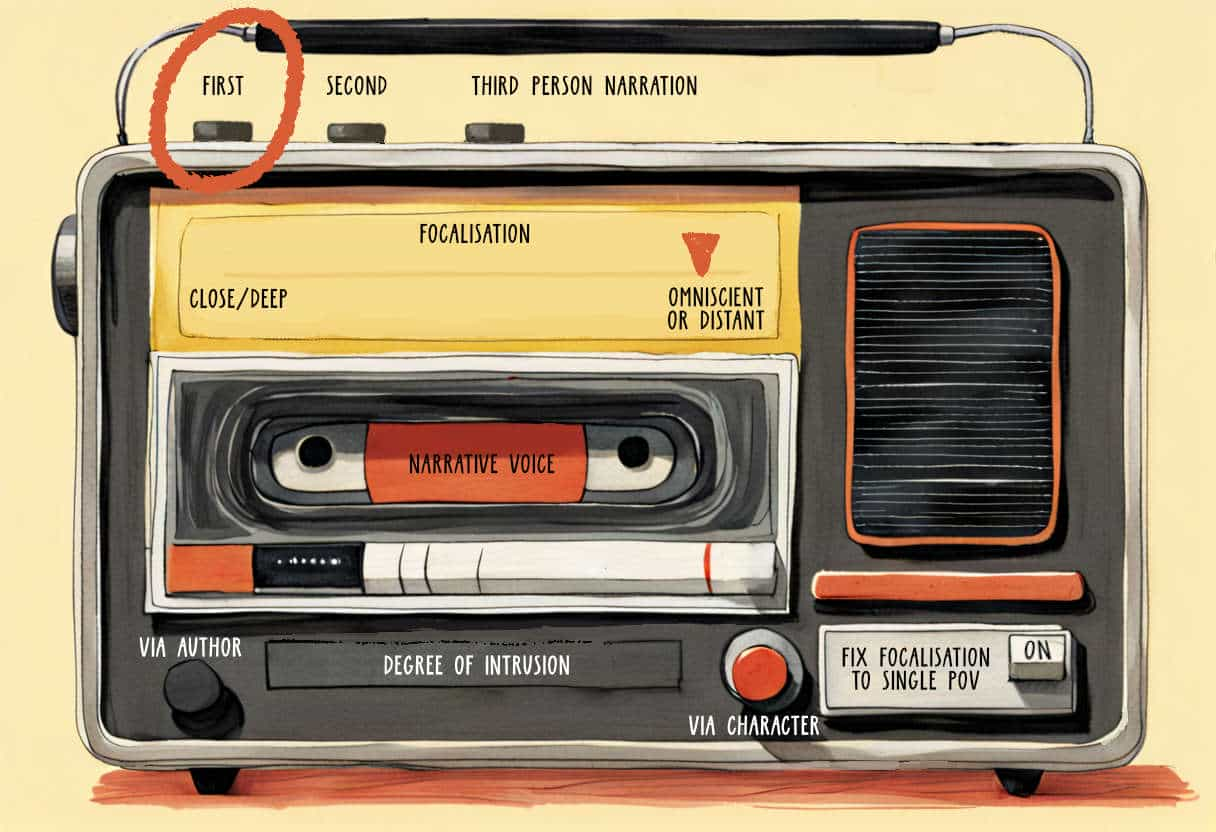

Joyce Carol Oates has written this story in ‘omniscient first person’. This is when a first person narrator has broad access to other people’s heads and tell us about places they could not have been.

This is an unusual choice, but not unheard of. Narration comprises various aspects. I think of first/second/third as three buttons, and imagine ‘focalisation’ as a dial, which doesn’t necessarily stay in one place.

At the very end of this story, Joyce Carol Oates ends with the narrator admitting she can’t have known all of these details, but she feels she understands everything anyway.

A much older example of first person omniscient is Madam Bovary, but there was a flurry of dead narrator novels which became popular after the publishing success of The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold. For more on that, see The Influence of The Lovely Bones. As is very common in reading fashion trends, the omniscient first person via dead narrator first became popular in young adult literature then moved up into adult fiction. (It far less frequently happens the other way around.)

For much of the story, the narrator functions as the viewpoint character. The twins and Whipple are the ‘main characters’. This switches over at the end, where the narrator is the main character of her own affair. This elevates the story to one about a community rather than an individual, and stories about a community are far easier to write when the focalisation dial is set mostly at the omniscience/distance end.

Short stories set in small towns with violence at their core are frequently written with a lot of focal distance. Another excellent example is “Brokeback Mountain” by Annie Proulx.

SHORTCOMING

SHORTCOMING OF THE TOWN AS A WHOLE

This small town does not understand the psychological needs of an unusual young man by the name of Whipple — son of the ice makers — and fail to foresee his violent potential.

This short story was written in the early 1990s before Aspergers became part of the DSM (later revised to Autism), but I think many readers today will recognise Autistic traits in the character of Whipple.

I’d like to point out that autism in itself is not a red flag for violence, but ostracization from your community by dint of being different and misunderstood most certainly is, especially when the person in question is a young man.

THE TWINS

The twins are mischievous, running to amoral. They steal from their own grandmother, but their morality is complex: They’ll happily share the spoils with other girls. Their naughtiness is childlike, and the fact that they are identical twins (in temperament as well as in looks) only seems to make them more like themselves. They egg each other one, providing each other with confidence to do as they like.

Rhea and Rhoda Kunkel are the youngest children of a very large family, so they are largely unsupervised, unprotected from danger.

In contrast, the narrator mentions no siblings, and is better protected from danger by her mother.

DESIRE

Summer seems to last forever when you’re a kid. The twins are active, healthy, robust and full of the joys of life and whatever they get up to serves to assuage the utter boredom of smalltown mid-century summer holidays. They attract other children because they are just fun to watch and to be around.

OPPONENT

Whipple is the Minotaur opponent — the opponent a community comes to fear, and which binds the rest of inhabitants together.

PLAN

The interesting thing about this story is, it’s more difficult than usual to define any ‘plan’, not even on the part of Whipple, who probably acts very badly due to lack of inhibition. The twins just want to have fun, as does the young narrator.

Even as an adult woman, the narrator ‘just wants to have fun’. As a child she removed her clothes for fun with the girls, who were murdered a short time after, and now she does it again with a sexual partner, as if to rewrite the collective trauma of her childhood.

Dealing with trauma by returning to the spot and attempting to ‘tape over’ an earlier incident is not uncommon. Jon Krakauer writes about this phenomenon in relation to college r*pe victims in his non-fiction book Missoula.

Missoula: R*pe and the Justice System in a College Town

“Missoula, Montana, is a typical college town, with a highly regarded state university, bucolic surroundings, a lively social scene, and an excellent football team the Grizzlies with a rabid fan base. The Department of Justice investigated 350 sexual assaults reported to the Missoula police between January 2008 and May 2012. Few of these assaults were properly handled by either the university or local authorities. In this, Missoula is also typical. A DOJ report released in December of 2014 estimates 110,000 women between the ages of eighteen and twenty-four are raped each year. Krakauer s devastating narrative of what happened in Missoula makes clear why rape is so prevalent on American campuses, and why rape victims are so reluctant to report assault.

After writing this book, Jon Krakauer was emotionally exhausted, and said he wasn’t going to write another book ever again. (So far, he seems to be sticking to that.) Krakauer’s book is especially important because too many people will only listen to an explanation of r*pe culture when it is delivered by a man.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Whipple murders one twin, then the other, in a sequence which has been imagined in detail by the fascinated intradiegetic narrator.

ANAGNORISIS

By utilising the first person narrator rather than a more detached one, Oates has the following advantages:

- We don’t get caught up in questioning the narrator’s reliability. Instead we can focus on what might have really happened.

- There’s a double confession at the end: One, the narrator had an affair. Two, she’s invented much of the story about Whipple and the twins. This is the narrator positioning herself alongside Whipple. She’s not a murderer, sure, but she’s admitting her own susceptibility to ‘heat’ — in her case, the heat of passion rather than the violently angry kind, though any kind of passion can be destructive if we are not careful. She has at some point decided to conduct this affair in the very same house as the murders took place, which is an unlikely thing to happen in real life, but works nicely in a story because this further aligns the heat of the narrator with the heat of the murderer, and lets readers know that anyone can succumb to hot passion. We all have it in us.

NEW SITUATION

The narrator has confessed something to us: She has done this immoral thing by having a three-year-long extramarital affair, in which she risked losing her husband and children. Yet she did it anyway, due to ‘heat’.

When narrators confess things on the page, this is their way of working things through in their head. A question we can ask of fictional confessors: Where are they in their processing journey? Have they got it about right? Or do they still have a massive blind spot?

I am left with the impression that this woman has a clear-eyed view about her own moral shortcomings. Not only that, she mostly understands why she behaved the way she did — it’s not so easy for people in real life to draw a connection between a present behaviour and a past trauma. But this woman has done it.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Mind you, Joyce Carol Oates stated in her introduction that she set out to avoid readers making causal connections.

Yet this reader has done exactly that, because of a well-known cognitive bias in which we create cause and effect narratives in hope of understanding them.

Sequential causality is generally considered to be very important in plotting. It is often thought to be the difference between a simple story, which just presents events as arranged in their time sequence, and a true plot, in which one scene prepares for and leads into and causes the scene that comes after it.

Rust Hills

So for me, the narrator did Y because of childhood X. It’s nowhere near as simple as that, of course. A sexual act, forbidden or not, is not at all the same thing as murder, so the story encourages juxtaposition and contrast as much as it encourages a causal link.