1. MIYAZAKI’S FILMS FEATURE A TECHNIQUE CALLED ‘PILLOW SHOTS’

A “pillow shot” is a cutaway, for no obvious narrative reason, to a visual element, often a landscape or an empty room, that is held for a significant time (five or six seconds). It can be at the start of a scene or during a scene.

Dangerous Minds

It comes from the famous director Yasujiro Ozu and is common in Japanese cinema. Why are they called pillow shots? It’s the cinematic equivalent of ‘pillow words’ used in Japanese poetry. A pillow word represents a sort of musical beat between what went before and what comes after. It functions as a kind of punctuation, signalling the end of something and a transition to something else.

Similarly, silence plays an important part in Japanese films, and Hayao Miyazaki doesn’t subscribe to the Dreamworks school of thought, in which kids need action from the get-go.

Although it looks as if nothing is happening in some of Miyzaki’s pillow shots, Japanese animators are more likely to use dynamic backgrounds and Western animators to use static ones. For instance, something in the Japanese background will be in motion and change. Even when there’s action going on in the foreground, Miyazaki will quite likely have something going on in the background.

2. THE ENGLISH DUBS AREN’T ALL THAT GREAT

The English translations of Miyazaki movies are often quite different. For example, the agency of Sophie is taken away somewhat in the English dub of Howl’s Moving Castle. Regional dialects are lost when they are dubbed into standard American English. Voices are quite different, also. Miyazaki’s children’s voices tend to be authentic child voice actors whereas sometimes Hollywood uses an adult to mimic a child.

Also, the English dubs tend to put words in where there were none, under the assumption that a young Western audience needs them. In Kiki’s Delivery Service, several additional words and sounds occur at moments of silence in the original.

3. MIYAZAKI’S FILMS TEND TO STAR GIRLS BUT THEY ARE ONLY ‘FEMINIST’ IN THEIR OWN, OLD-FASHIONED KINDA WAY

Traditionally, liminality has been associated with both [sic] sexes, from young male heroes such as those described in Joseph Campbell’s Hero of a Thousand Faces who undergo various forms of initiation rites, to the Bacchae of ancient Greece or the shamannesses of premodern Japan who exist for sporadic periods outside of mainstream culture. Recently, however, the notion of the female rather than the male as a conduit into liminality has become more ubidquitous, especially in Japanese culture, with the ascendance of the figure of the shojo. The shojo, as John Treat describes her, is a “barely and thus ambiguously pubescent woman” … who is attached to what could well be called a “betwixt and between culture” — what Treat describes as so-called “kawaii” or “cute” world made up of “cousins, boyfriends, and favorite pets,” as well as stuffed animals and related paraphernalia such as “Hello Kitty,” whose cuteness has taken on almost iconic significance in the leisure world of young Japanese.

Susan J. Napier, The Journal of Japanese Studies Vol. 32, No. 2 (Summer, 2006), pp. 287-310

See: John Treat, “Yoshimoto Banana Writes Home: The Shojo in Japanese Popular Culture in Contemporary Japan and Popular Culture, 1996

See also: My post on cute and kawaii.

4. BUT WHEN DISNEY’S MARKETING DEPARTMENT GETS A HOLD OF MIYAZAKI FILMS THEY MAKE THEM LESS FEMINIST THAN THEY WERE IN THE FIRST PLACE.

6. HAYAO MIYAZAKI USES A WIDE RANGE OF CLASSIC LITERATURE AND BUILDS ON IT.

The name ‘Laputa’ (from ‘Castle In The Sky’) is derived from Jonathan Swift’s novel Gulliver’s Travels, wherein Swift’s Laputa is also a flying island controlled by its citizens. Anthony Lioi feels that Miyazaki’s Laputa: Castle in the Sky is similar to Swift’s Laputa, where the technological superiority of the castle in the sky is used for political ends.

7. THERE’S THIS JAPANESE CONCEPT CALLED ‘MA’

When Roger Ebert asked Miyazaki about the “gratuitous motion” in his films—the bits of realist texture, like sighs and gestures—Miyazaki told Ebert that he was invoking the Japanese concept of “ma.” Miyazaki clapped three times, and then said, “The time in between my clapping is ma.” This calls to mind the concept of temps morts, or dead time, in the European art cinema of the 1960s. Temps morts is a pause, a beat, a breath, a moment that doesn’t advance the plot. But far from being dead, Miyazaki’s moments of “ma” are full of life—there is a simple joy in watching his worlds move. In “animating”—breathing life into—a world that looks like our own, Miyazaki carries forward a spirit from the very beginning of film history.

Bright Wall Dark Room

8. THE FILMS ARE COMMONLY REFERRED TO AS ‘MAGICAL REALISM’

For more on magical realism see the blog posts by Michelle Witte.

However, there is a case to be made for reserving the word for specifically Latin American literature using magic to explore ideas of colonisation. To avoid this appropriation there is another word we can use: fabulism.

9. HAYAO MIYAZAKI IS A WORLDWIDE INFLUENCE ON OTHER STORYTELLERS

Take 2017 Netflix series Okja as an example.

Kong: Skull Island is another: “Director Jordan Vogt-Roberts took a page from Miyazaki’s playbook and decided to focus on the unique spirit of all living creatures.”

Lilo and Stitch, too, was apparently influenced by Hayao Miyazaki. “Kiki’s Coffee House” was inserted into the movie as a tribute.

[Miyazaki’s] stories are everything but cliché. There’s never a cliché I’ve ever detected in his stories; the storylines are completely original and the way the characters interact is very believable. I think that’s one of the things that inspired us to rewrite the book in the way our characters interact. You referenced that when we were talking about the scene with the sisters yelling at each other. It’s so natural and cathartic to see that going on. When characters interact believably, you believe in them and it makes it seem much more real to you. One of the big reasons we didn’t have this film as a musical in the traditional sense is that the minute a character begins to sing, it places that film in a certain realm, a musical realm, which is great but it’s not really happening the way we wanted this film to feel like it’s happening.

Chris Sanders

Specifically, if you reference a film like Miyazaki’s My Neighbour Totoro, that film shares a lot of similarities with ours. We were inspired by the way Miyazaki created realistic relationships between the human characters, the sister-sister relationship, and wove in a realm of fantasy and whimsy very subtly. It’s done in such a believable way… You’ve got these fantastic elements and yet you feel like you watched a story that really existed between a family.

Dean DuBlois

Ubisoft’s Child Of Light was also influenced by Miyazaki, particularly the hand-drawn look of the art.

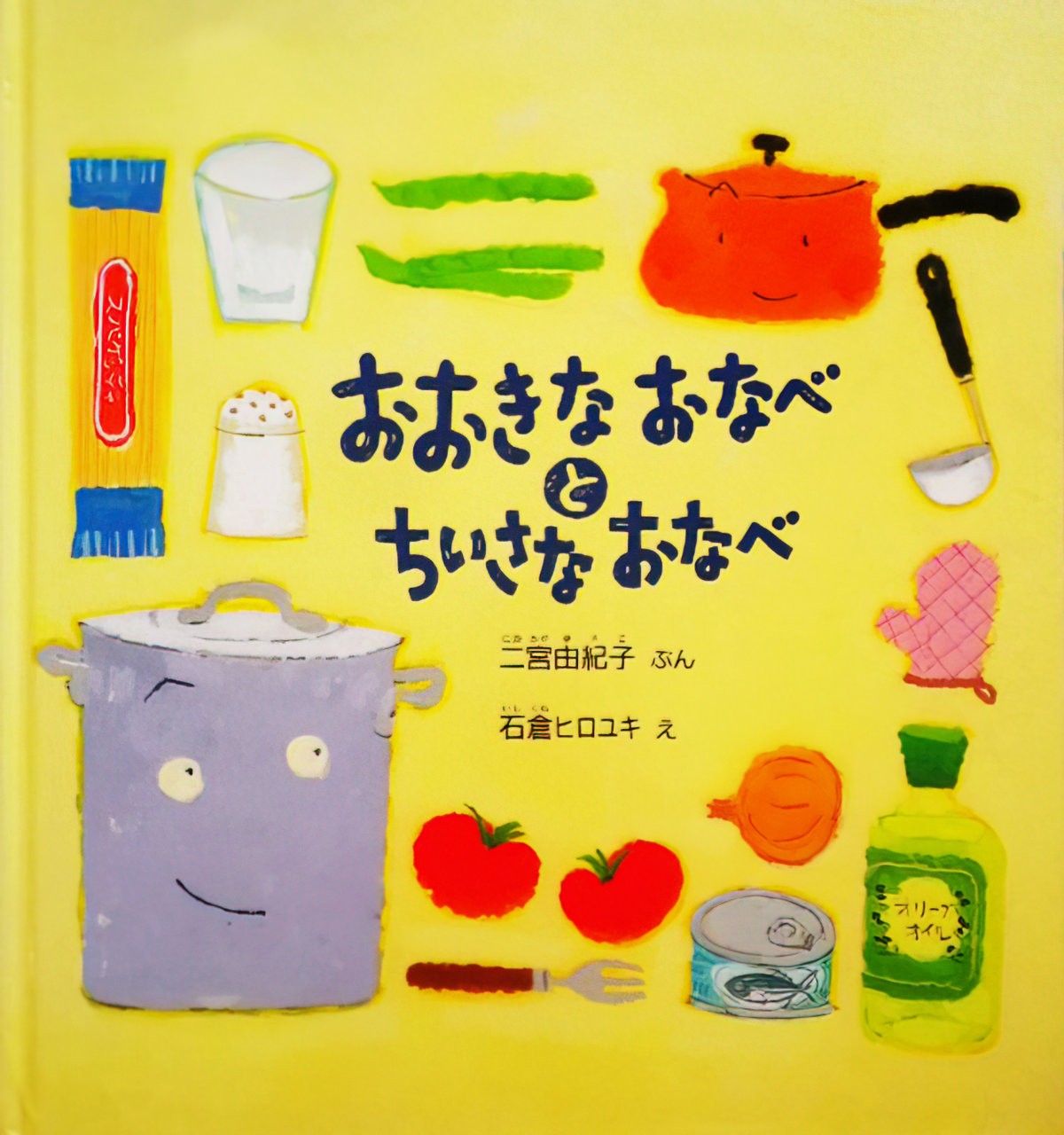

10. HAYAO MIYAZAKI LOVED BOTH JAPANESE AND IMPORTED CHILDREN’S BOOKS

Like a disproportionate number of adult story creators, Hayao Miyazaki was a ‘physically weak’ child and the time not spent on running about was spent reading. Bibliocommons has a list of Miyazaki’s favourite children’s books showing that (of course) he didn’t just enjoy stories for and about boys, but loved stories about girls equally. Miyazaki didn’t stop reading children’s books just because he stopped being a child, either.

11. HAYAO MIYAZAKI IS THE ULTIMATE PANTSER

A plotter describes a storyteller who works out the plot outline before fleshing it out. They know the ending before even starting to type. A pantser is the opposite of this, working out the plot as they go along. Miyazaki is the ultimate pantser because he has an entire studio working for him, under his direction, and none of these people knows how the story is going to progress. Hollywood doesn’t work like that. Scripts undergo numerous revisions and workshopping before filming begins. For this reason, the Studio Ghibli plots feel quite different from Hollywood blockbusters, and even more meandering than most indie films. For Miyazaki, the main thing is emotion. Emotion is first and foremost; plot is secondary.

Miyazaki also never studied screenwriting.

12. VILLAINS ALSO DEVELOP AS CHARACTERS

Miyazaki’s baddies are rounded characters in their own right. There’s no clear line between good and evil. An example of a character who is ostensibly a villain but who has a soft side is No Face from Spirited Away. He begins as greedy but becomes an ally.

There’s no binary of good and evil. These two things coexist in the same characters. The protagonist doesn’t win, but grows and adapts to a world that isn’t built to their needs.

Characters begin flawed and end flawed. There’s not the same sort of character arc as we are accustomed to in the West, though writers such as Matt Weiner have embraced this realism. Don Draper never really evolves, either. The goal in a Miyazaki movie is to develop emotionally. Any external goal is secondary. Western stories tend to use an external goal as a metaphor for internal change.

Whereas the humans in Miyazaki films have complex emotions, the fantasy characters do not. We are never let in on what they are thinking. They remain mysterious to us. Mysterious creatures hold our attention in a way that an empathetic human character does not.

13. FLIGHT IS VERY IMPORTANT

Miyazaki’s father owned a plane company and Hayao is fascinated with flight. Every single one of his movies contains a flight scene, or a scene in which a character sees something from a long distance. More on the symbolism of flight.

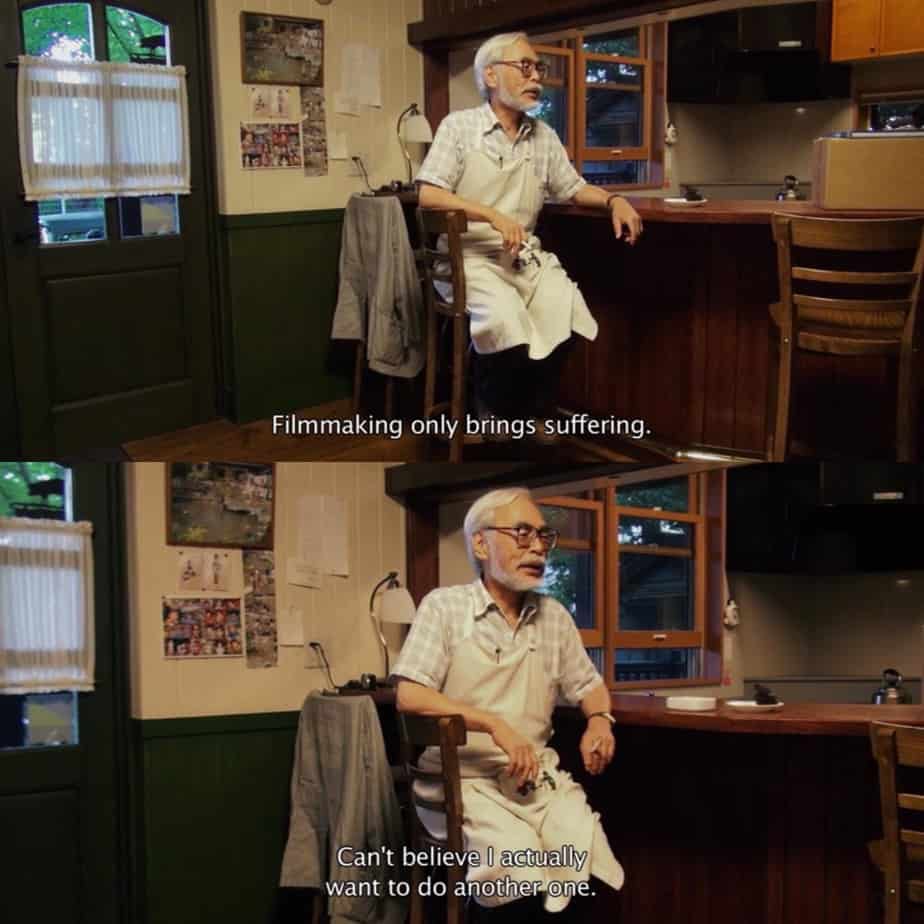

14. MIYAZAKI DESCRIBES HIMSELF AS A PESSIMIST

But doesn’t want that to come through in his movies. He wants to offer young viewers a sense of hope. This reality versus aspiration is evident in each of Miyazaki’s films — the themes demonstrate that the mind of the creator is focused on issues such as corporate greed and environmental destruction, but the endings of the stories are still hopeful.

15. MIYAZAKI DOES NOT LIKE HIS STUDIO DESCRIBED AS ‘THE JAPANESE DISNEY’

Far more accurate to call him ‘The Japanese Yuri Norstein’. Norstein (or Norshteyn) is a Russian animator born the same year as Miyazaki (1941). These men have lived through the same world events. Take a look at a few of his productions and you’ll see the similarities. Hedgehog in the Fog is his best-known work in the West:

16. THE AUDIENCE FOR GHIBLI MOVIES AREN’T JUST CHILDREN

Certain films such as Totoro and Ponyo are written with young children in mind. But when stories are written to appeal to human emotion, there is no upper age limit. Miyazaki works under the principle that children don’t necessarily have to understand what they see right away — they can see something now and understand it later. That’s just fine with him.

17. GEKIGA, NOT MANGA

Miyazaki began his career as a manga artist and is influenced by a type of manga called ‘gekiga’. This literally means ‘dramatic pictures’. It was a term coined by manga artists who wished to separate their own work from ‘less serious’ cartoonists. Creators of gekiga tend to depict more realistic humans and backgrounds. Miyazaki has no love for the manga industry in general, and its cheap tricks to get an audience reaction. He avoids large, flashy moments in favour of small, subtle ones.

18. ANIMISM

Animism is the belief that objects, places and creatures all have a distinct spiritual presence. Even rocks, weather systems and certain words are considered animated and therefore alive.

Miyazaki believes people to be part of nature — this is the traditional Japanese way of thinking, unlike in other major world religions, in which humans (specifically male humans) are thought to be at the top of some tree of life, with animals placed her for our own use.

19. HILLS, VALLEYS, COVES AND CLIFFS

Miyazaki’s films rarely take place on flat landscapes. Japan, too, outside the megacities, is hilly. In stories, these features of land elevation are symbolic.

20. WEATHER AND EMOTION

Human sensibility is also conveyed via the weather. Rain, wind, sunshine — these mirror the emotions of the characters. This is called pathetic fallacy.

RELATED

How the Films of Hayao Miyazaki Work Their Animated Magic, Explained in 4 Video Essays