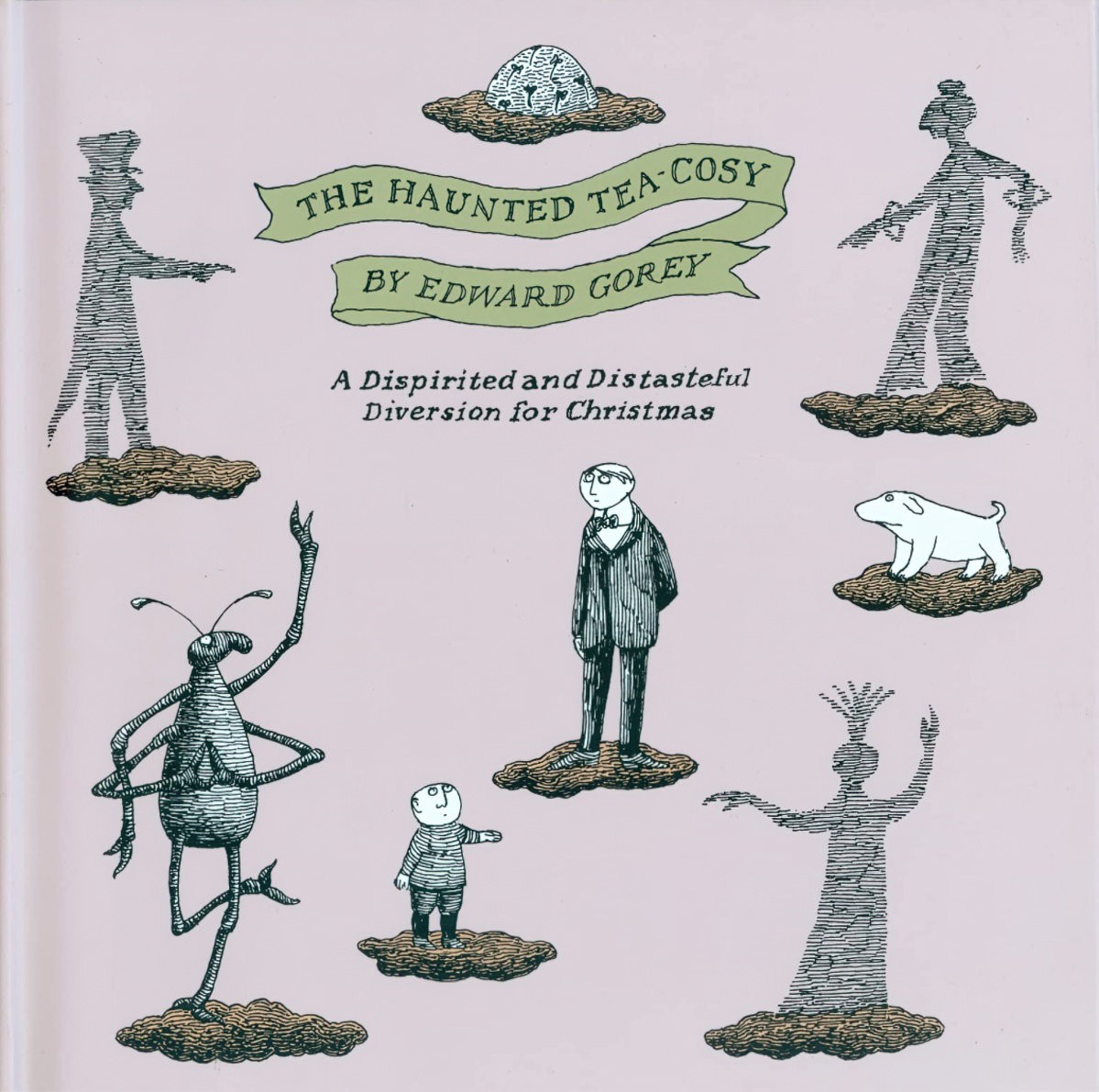

Edward Gorey was an American writer and illustrator who died in the year 2000. The Haunted Tea-Cosy: A Dispirited and Distasteful Diversion for Christmas is a picture book for adults, based on the cartoons first published in the December issue of the New York Times Magazine, 1997. Bloomsbury picked it up in an early-Internet era to introduce Gorey to British readers. This was therefore Gorey’s second-to-last book.

In the preface to “A Christmas Carol,” Charles Dickens wrote that he tried “to raise the Ghost of an Idea” with readers and trusted that it would “haunt their houses pleasantly.” In December 1997, 154 Christmases later, the “New York Times Magazine” asked our Edward Gorey, “the iconoclastic artist and author, ” to refurbish this enduring morality tale. What is Gorey’s moral? Don’t eat fruitcake? Don’t look for morals? Don’t mess with the classics? Whatever. You decide. But don’t think too hard, and have a Merry Christmas.

marketing copy

‘To believe in [a ghost] is to believe not only have the dead the power to make themselves visible after there is nothing left of them, but that the same power inheres in textile fabrics’

Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary (1906)

INSPIRATION

I wonder if Gorey ever had the experience of enjoying a cup of tea only to find himself swilling a beetle. My father still speaks of the time he had a cockroach in his mouth. I had my own taste of this medicine when I recently found an earwig in mine. Unfortunately for me, I was drinking tea at the house of a new acquaintance and had to deal with this episode discreetly. (I believe I managed it.)

DESCRIBING EDWARD GOREY

Edward Gorey’s work tends to be described as:

- Surreal (that word may not mean what you think it means)

- Gothic

- Metafictive

- Victorianist (A Christmas Carol was published in 1843 and takes place in the early 1800’s.)

- Whimsical (yes, both gothic and whimsical)

- Absurdist

Up front, I’d get more out of it if I could be bothered reading the source of the spoof from cover to cover — A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens. For reasons I’ve yet to palpate, I find that story and all movie adaptations immensely boring, but it’s such a tentpole narrative that I’ve absorbed the general gist: A miserly old man fails to enjoy Christmas, is visited by three scary ghosts and after this trauma learns not to be miserable — because it’s Christmas, after al, and Christmas is based on the old carnivalesque tradition and you are going to hav fun at dinner with the rellies, dammit. Perhaps it’s the didacticism that repels. Perhaps it’s the unscary ghost which fails to entice?

In any case, A Christmas Carol is ripe for parody because by the end of the 20th century, audiences were no longer down with such moralising works, not even for kids. But in other ways Charles Dickens remains fun — no one surpasses him for character names. Edward Gorey certainly had fun with that in “The Haunted Tea-Cosy”. (The man himself had a remarkably symbolic name, also known as an aptronym.)

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE HAUNTED TEA-COSY

Does this series of cartoons have a classic story structure? Does it build to anything? At first read it feels deliberately random — an integral part of its humour — the so-called anti-plot. This is a consciously non-didactic story — the grandiose moral of ‘don’t be a miser’ is demoted.

Gravel and his companions found themselves at a great distance somewhere to the north.

Why are they in the north? No reason given. None needed. But Gorey is well aware of the symbolism of the North — North equals desolate and cold.

The marketing copy suggests ‘don’t eat fruitcake’ as a moral but there is really nothing to learn — any takeaway message is this: The world is bizarre. Revel in life’s inherent absurdity. Don’t even bother looking for connections. If you see any cause and effect relationships, well, that’s on you.

Gorey was also well-attuned to heart-rending melodrama, exhibited best in the graveyard scene:

A small orphan called Nub and a large stray dog named Bruno huddled against a tombstone whose inscription was worn away.

Nothing says pathetic like orphans and stray dogs. Read Grimm versions of Cinderella and you’ll find, quite often in the German fairytales, the main character found herself weeping beside her dead mother’s grave.

But even melodramatic parodies need something to hang it together:

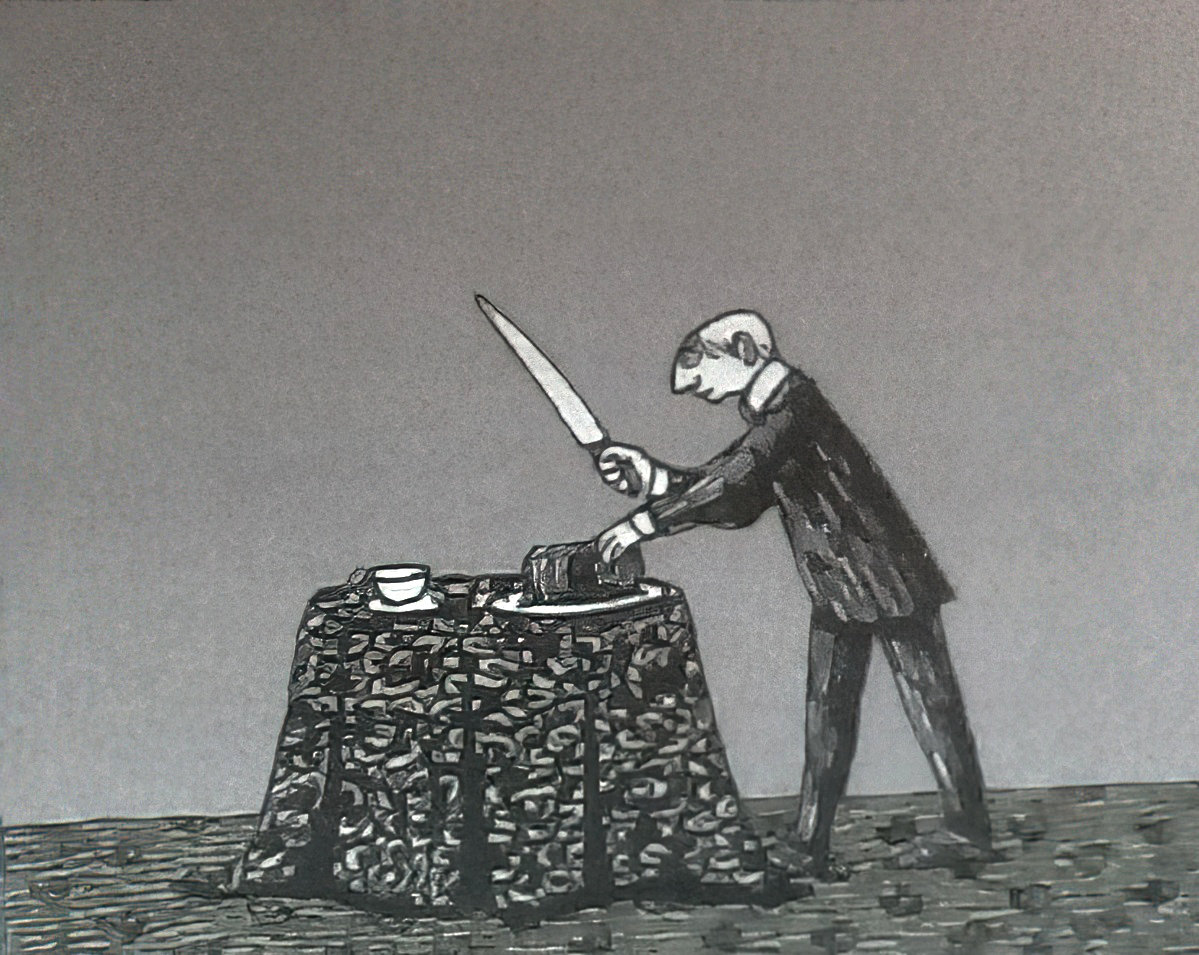

Edmund Gravel sits down for tea on Christmas Eve, cuts a slice of fruitcake, and is immediately visited [INCITING INCIDENT] by the Spectre of Christmas That Never Was, the Spectre of Christmas That Isn’t, and the Spectre of Christmas That Never Will Be. Guided on his spectral [MYTHIC] journey by the Bahhum Bug, Edmund is taken through his village of Lower Spigot and shown [METAFICTIVE] Affecting Scenes, Distressing Scenes, and Heart-Rending Scenes.

Goodreads reviewer, links are mine

The thread running through this story is a crime plot — the case of the missing wallpaper (wholly unconnected to the teapot, which is your classic McGuffin.

Alberta Stipple has her wallpaper stolen; it is subsequently found buried in a graveyard when grave diggers are excavating a misplaced coffin.

Detectives turn up to inform Lady Snaggle at her ancestral home that ‘her husband’s brains’ (note the funny phrasing) were behind an international gang of wallpaper thieves.

The story of Gravel and his bug are a mock-framing story, meaningfully disconnected (from what I can tell) from that crime plot, though perhaps someone will enlighten me on that.

The ending is abrupt, a relative of the Shaggy Dog ending, in which we realise we’ve been strung along with a non-story and its anticlimax. But! We are left with a satisfying sentence:

Giggling, dancing and shrieking prevailed and, as the evening wore on, were carried to the very edge of the unseemly.

The final word of that sentence, ‘unseemly’ is ironically underwhelming, as the ending is itself.

EDWARDIAN BOOK DESIGN, SYNTAX AND ILLUSTRATIONS

ILLUSTRATION NOTES

“The Haunted Tea-Cosy” is designed to emulate a printing era in which colour was expensive and illustrations were separate from text (recto vs verso). A Christmas Carol was published in the Edwardian era, though it’s set ambiguously in the Georgian or Victorian era.

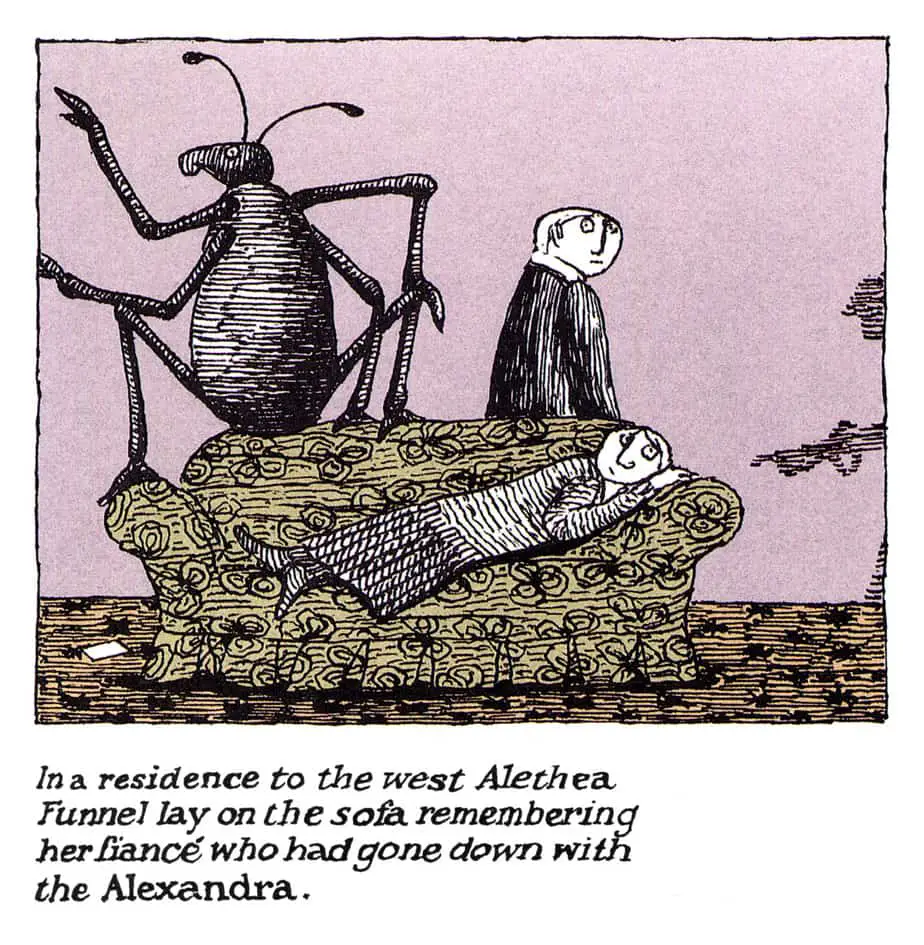

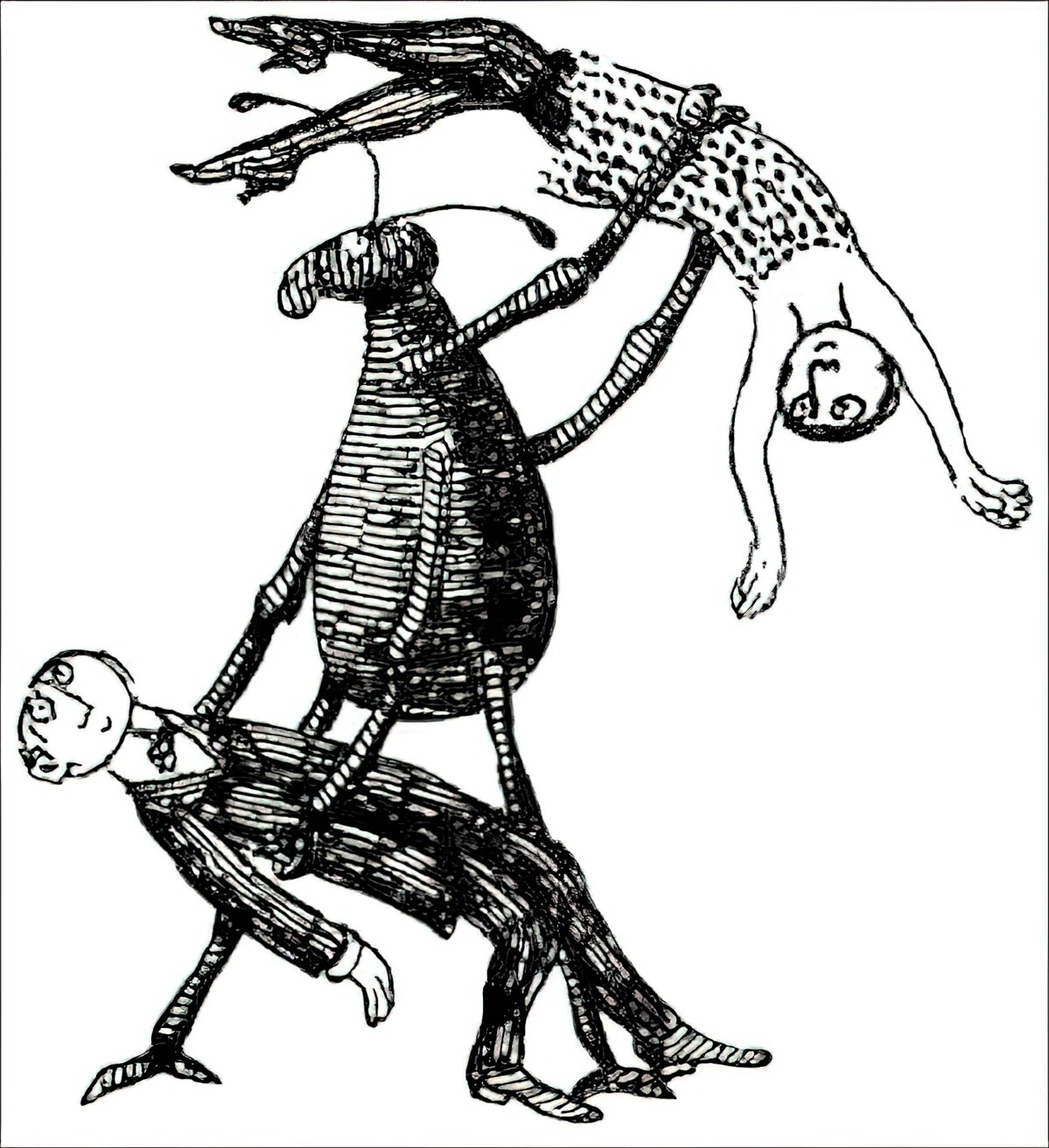

Edward Gorey drew using a combination of techniques. He makes metafictive reference to ‘stippling’ in one of the character names of The Haunted Tea-Cosy. If you’re logged in to Pinterest, there’s a collection of his techniques here. Gorey was well-known for pen and ink — no gradations of shading. In “The Haunted Tea-Cosy” he depicts the semi-transparent ghosts with a series of short lines in the shape of a person — the gap between the lines symbolises the overall transparency. (If he were making use of, say, pencil, he could’ve pressed more lightly, but that was not his tool.) This is how Gorey created the full range of values — by leaving varying amounts of space between the lines. This would have been very Zen, I imagine.

The composition of the illustrations is, however, that of a modern comic picture book such as Mo Willems often creates. Even the limited, dusty pastel colour palette is similar.

WORD CHOICE AND SYNTAX

Gorey is using the same sentence structure over and over, which serves to make it stand out. It includes commas used like parentheses to incorporate detail which is funny but also diverting (in the literal sense) because while these details are being described, something massive is happening:

The tea-cosy suddenly twitched and from beneath it leapt a creature many times the size of the space within, even if it had not already held the teapot.

Emphasis on the dimensions of the teapot are beside the point, sort of, because how on earth could something that big come out of there? We accept such things in stories though, so Gorey is making fun of our willingness to suspend disbelief, metafictively pulling us out of such inclinations.

I’m sure I don’t get half the jokes in subsequent scenes involving the subsequent ghosts, who are switched out for some reason I don’t understand because I’ve not read Dickens’ version. They visit one house after another and find each household involved in their own trivial disputes:

Next door but one the Edgar Grapples, Senior and Junior, had an argument as to what day of the week it was.

(Oblivious to the fact that they are accompanied by a visiting ghost.)

The third makes his first visit to Alicia Grumble:

Alicia Grumble woke in the night unable to think where she had put her Bible.

The illustration says it, but why is she looking for her Bible? This part of the story has been elided from the text: She is looking for her Bible to pray the ghost away, who has just turned up in her room. Or maybe not. Maybe that’s just me, making too much of connections.

The vocabulary of “The Haunted Tea-Cosy” is deliberately hifalutin, similar to how short story writer Saki made use of big words in a comical manner. Douglas Adams, to a lesser but noticeable extent, and various other comic writers.

- ‘Alfreda Scumble was abstracted from the veranda’ (notice also use of the passive — contemporary writers are encouraged to avoid it where possible, probably because we’ll end up sounding like a Victorian parody)

- The ghosts are described as ‘subfuse but transparent personages’. I had to look up ‘subfuse‘. It means dirty and swampy — ironically, you wouldn’t except ‘dirty’ on something ‘transparent’. Hence the ‘but‘.

- ‘at which the Bug declared in a minatory tone…’ (minatory means expressing or conveying a threat)

- ‘the bug declared in an admonitory tone’ (this is why writers are urged to stay away from non-ironic adverbs in dialogue tags)

- cynosure — a person or thing that is the centre of attention or admiration. ‘The cynosure was a cake taller than anything else in the room…’ But Gorey does not reward the reader by SHOWING us this cake, supposedly the centre of the wrapper story. No, he leaves it off the page. The characters are looking to the right upper corner. Those of us accustomed to picture books turn the page expecting to be rewarded for our time but nope, still no cake. Instead, they are dancing. (The dance is clearly an expressionist dance rather than a jovial one.)

INFLUENCES

Gorey influenced various modern artists such as Tim Burton, who has in turn been emulated e.g. the creators of ParaNorman. Less directly, Gorey has also been an influence on Gary Larsen (via B. Kliban) whose comic panels you’ll know as The Far Side.

Gorey himself was influenced by Dracula, which he came across at a very young age.

SEE ALSO

Gregory Maguire is another modern author sometimes asked to re-vision old tales for Christmas. I enjoy “Matchless“, a take on “The Little Match Girl“.

How Edward Gorey Illustrated Three Classic Fairytales from io9

If you like Gorey, check out Ivor Cutler.