“The Haunted Boy” is a 1955 short story by American writer Carson McCullers, who writes of adolescent boys as adroitly as Alice Munro writes of adolescent boys, focusing on their softness, and the conflict that derives from needing to look manly while not feeling at all strong in the face of adversity.

“The Haunted Boy” explores the struggles of Hugh as he deals with issues of adult imitation, lack of a strong male role model, peer loyalty, and emotional repression.

Ashley-Ann Woods, Adolescent Transformation in the Short Stories of Carson McCullers

Note that I use they/them pronouns when talking about McCullers. We can’t know how they would have self-identified had they been born, say, 80 or 90 years later, and there’s ample evidence to support an argument of gender queerness in this 20th century author. ‘They’ is non-committal on my part. “The Haunted Boy” is an excellent example of how Carson McCullers seemed to straddle genders. They show an intuitive understanding of the strictures around mid-century masculinity, and how women stepped up to perform the emotional labour of caring for boys and men, because men were not permitted to do so.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS FOR “THE HAUNTED BOY”

- When Hugh arrives home from school, he notices the flowers. What is the symbolic significance of the flowers?

- Hugh’s friend John is two years older than Hugh. Do you think this friendship dynamic would have worked if the boys were the same age? Why or why not?

- What is Milledgeville and how do the people of Georgia feel about the place?

- What was the cascade of issues that happened with Hugh’s family in the past year, and what incident marked the beginning of it?

- At what point in the story do you realise Hugh wants John to come upstairs with him because he is terrified?

- In front of John, Hugh pretends to be more manly than he is. What evidence from the text supports this?

- Describe how Carson McCullers makes use of colour symbolism.

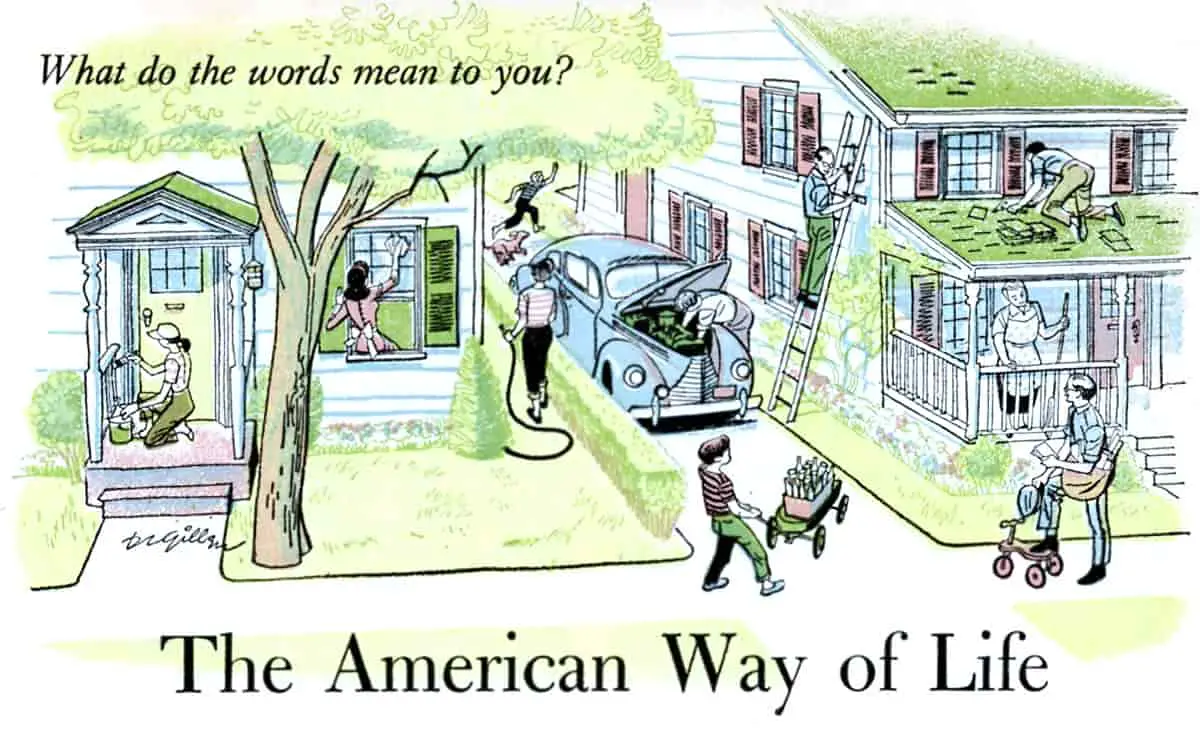

- Which symbols of cosy 1950s suburbia does McCullers use in “The Haunted Boy”, and how is this cosiness punctured?

- What is the symbolic significance of Hugh’s mother’s slip, which shows beneath her new dress?

- It has been noted that Hugh’s father, Mr Brown, is one of the few positive father figures in McCullers’s fiction. Do you agree that Hugh’s father is a positive influence? At the end, Hugh’s father gives him a compliment and reassures him about turning sixteen. What do you think the father means by telling his son that, “Nobody can be nervous before they are sixteen years old. You have a long way to go”? Do you think Hugh’s father is a helpful role model to his growing son? Why and why not?

SETTING OF “THE HAUNTED BOY”

PERIOD

1950s

DURATION

An hour or so

LOCATION

Georgia

A boy’s suburban home, in a 1950s America modern audiences can sometimes idealise. Note that Carson McCullers, too, clearly understood that the suburbs of the 1950s were a ‘snail under the leaf setting’, meaning if you take a closer look, you’ll find something unpleasant. For boys returning home from school to a mother in the home, who had lit the fire and baked a pie (the ultimate symbol of cosy 1950s American suburbia), the suburbs could be great. But for anyone who wasn’t a white man? Not so much.

ARENA

Between the front yard and the parents’ bed upstairs. There’s mention of a suburb beyond, with a school and also a hospital.

The hospital is called Milledgeville, a real hospital in Georgia. Around the world, mental hospitals like this one have been closed down and repurposed in the 21st century, with acknowledgement that incarceration is inhumane. Such places tended to be rife with abuse, including physical, sexual and over-medication.

If you’re old enough, perhaps your own town had such an institution nearby. For me growing up in 1980s and 90s South Island New Zealand, it was Sunnyside Hospital, formerly Sunnyside Lunatic Asylum, which finally shut its doors in 1999. Hugh exhibits in “The Haunted Boy” how people felt about these places: That they were for crazies. Hugh is at pains to tell John that his mother was only there for physical reasons. Alongside John, readers eventually learn that Hugh’s mother was first there for cancer treatment, and subsequently there for mental health reasons. Stigma was then as it remains, somewhat, today: Help for physical reasons carries far less shame than treatment for psychological reasons.

New Zealand’s most accomplished writer, Janet Frame, experienced Sunnyside as an in-patient. She was about to receive a lobotomy until she was saved by the fact that her short story collection won a major literary award. (You can read about that in her autobiography An Angel At My Table, which is also a film directed by Jane Campion.)

In this episode of Talk Nerdy, Cara is joined by Harvard University science historian Dr. Anne Harrington to talk about her newest book, “Mind Fixers: Psychiatry’s Troubled Search for the Biology of Mental Illness.” They take a fresh look at the history of mental illness, including the early asylum system, psychiatry’s current relationship with neurobiology, and what the future of assessment, diagnostics, and treatment may hold.

Insane Asylums w/ Anne Harrington

As the story progresses, McCullers repeats words such as: odd, crazy, asylum. These words describe to readers Hugh’s increasing sense that he is losing control of his own emotions, and also hark back to his mother’s recent institutionalisation. (At the time of this story, she has only been back home for a month.)

MANMADE SPACES

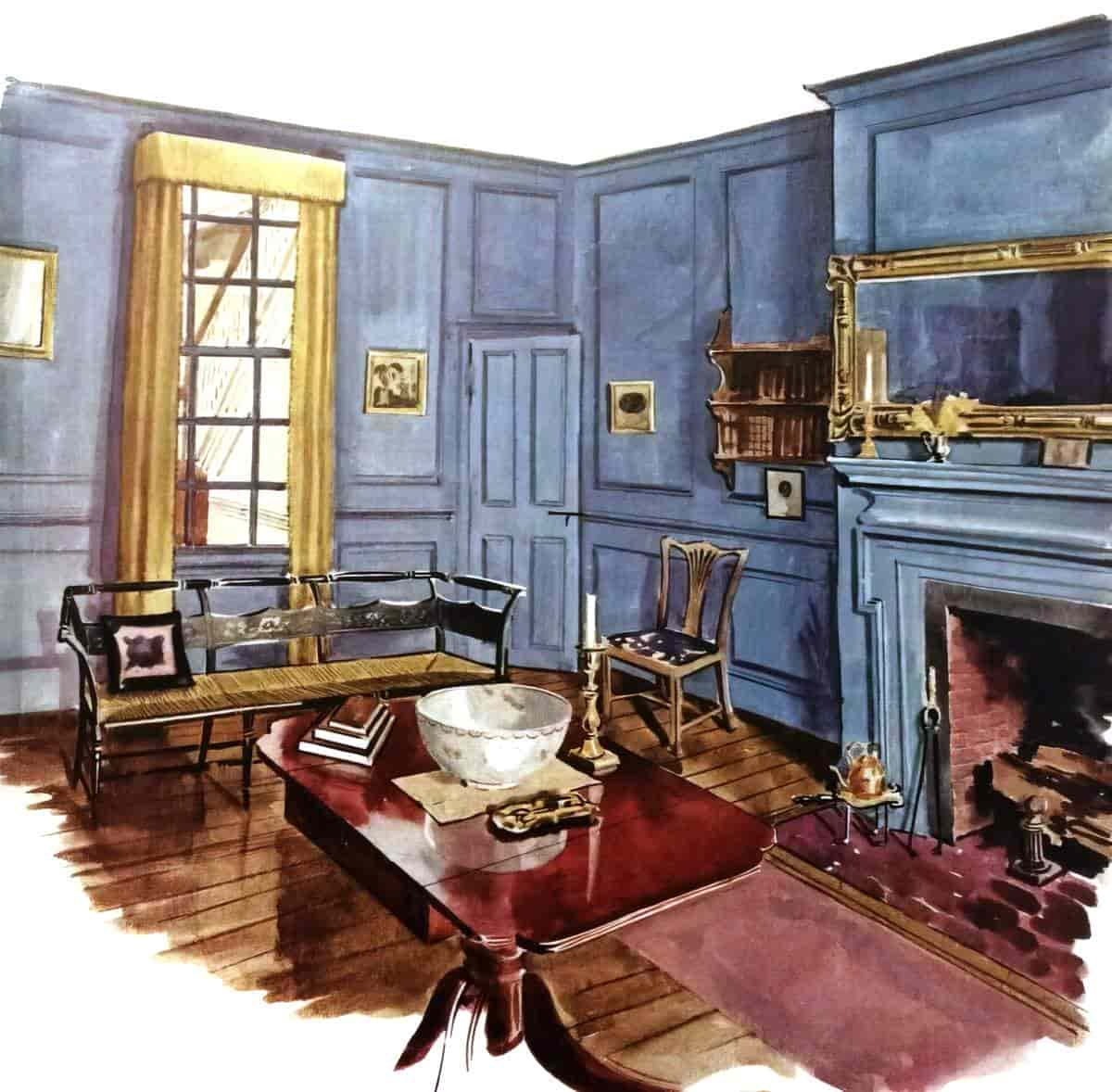

Hugh’s suburban house is a Symbolic Dream Home, with a downstairs and an upstairs.

Note that at the end of this story, Hugh will be left alone in the backyard, newly bolstered by his father’s words. The father has taken Hugh out of the feminine sphere of the house and into the masculine sphere of the outdoors.

Pay special attention to how Carson McCullers makes use of colour in this story.

- Hugh will first reject the colourful flowers as feminine because he is with his male friend.

- Later in the story he rejects his mother’s new clothing. She has purchased coloured shoes for the first time in her life.

- But once Hugh reveals his vulnerable self to his mother, he can truly admire her blue shoes.

- Blue is the symbolic inverse of red (blood, from a haemorrhage), so the blue dress should be a sign that times have changed.

- Related to this, Hugh is angry that his mother’s slip is showing because he’s uncomfortable, in this moment, with anything vulnerable and private which shows to others on the outside. Just as his mother’s slip shows, Hugh’s private feelings are in danger of being seen. (Note the double meaning of the English word ‘slip’. Petticoats ‘slip on’ easily. Masks can ‘slip off’ and occasionally reveal one’s true self.)

WEATHER

Pathetic fallacy, though not your usual kind (raining to mean tears). Today is ‘the first warm day’ after winter, which corresponds to the mother’s improvement, and will soon correspond to Hugh’s, as well.

SOCIAL MILIEU

Interestingly, John must rush off because he needs to sell tickets for Glee Club.

Glee Clubs started off as all men’s singing groups. The word ‘glee’ comes from Old English ‘mirth’ or ‘entertainment’. In music, glee is an unaccompanied song for three or more male voices.

Sociologists tell us that there are various forms of masculinity. The masculinity accepted in a male singing club is perhaps a softer kind, which would explain why Glee Club has so often been the refuge of LGBTQIA+ students over the decades. Hugh’s older friend John is also “the best athlete”, so is no doubt excellent at code switching between various types of masculinity. In this story, you’ll see him switching away from hegemonic masculinity to a softer, more nurturing kind. But John, too, feels the pull of hegemonic masculinity and rushes off to see his tickets rather than hang about to comfort his younger friend.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE HAUNTED BOY”

SHORTCOMING

Since entering adolescence, Hugh Brown has felt the need to repress his most difficult emotions around his mother’s recent illness. Throughout the story, Carson McCullers depicts childlike, feminine softness alternating with a Potemkin of a hard, manly exterior.

HUGH’S SOFT SIDE

- He knows the names of flowers

- He is dependent on his mother while also needing to look after her

- He was very much looking forward to having a little sister and choosing her name, which was ‘Crystal’, drawn to a pretty thing himself

- He enjoys writing poetry, which he shares with his mother

REJECTED FEMININITY

- Hugh’s mother has taught him the names of flowers. He knows them, but has now reached the age where tending to flowers is “fooling around” (code for: not something men can know about).

- Demonstrating knowledge of how his mother makes pie dough (a woman’s job)

- When John calls Hugh by his ‘sissy’ name (Hugh) he thinks this is because he hasn’t met the criteria for behaving like a real man. (Readers will see he is wrong about this. John is extending kindness.)

Sissy Insurgencies: A Racial Anatomy of Unfit Manliness (Duke University Press, 2022) by Marlon B. Ross focuses on the figure of the sissy in order to rethink how Americans have imagined, articulated, and negotiated manhood and boyhood from the 1880s to the present. Rather than collapsing sissiness into homosexuality, Ross shows how it constitutes a historically fluid range of gender practices that are expressed as a physical manifestation, discursive epithet, social identity, and political phenomenon. He reconsiders several black leaders, intellectuals, musicians, and athletes within the context of sissiness, from Booker T. Washington, George Washington Carver, and James Baldwin to Little Richard, Amiri Baraka, and Wilt Chamberlain. Demonstrating that sissiness can be embraced and exploited to conform to American gender norms or disrupt racialized patriarchy, he also shows how it constitutes a central element in modern understandings of race and gender.

New Books Network

training for expected MASCULINITY

- John is “not the least bit teacher’s pet” and the best at sport, which makes him the perfect masculine ideal.

- The boys have decided to call each other by their last names, military style. They only slip into addressing each other by first names again when the masculine mask drops away.

- Showing off a quicker way to make pie dough, using purchased crackers and smooshing them up, which is a more masculine action than lovingly rolling out and kneading the dough from flour.

- When John asks Hugh for a glass of milk, he turns it into a riddle. Carson McCullers has probably chosen milk because of its association with motherhood. John has probably asked for milk indirectly because catering might offend Hugh’s fragile sense of manliness at this point. (Note that this works. John is emotionally astute.)

- ‘Hugh could have answered no other boy. He had talked with no one about his mother, except his father, and even those intimacies had been rare, oblique. They could approach the subject only when they were occupied with something else, doing carpentry work or the two times they hunted in the woods together — or when they were cooking supper or washing dishes.’ When admitting to John how much his mother’s ill health has hurt him, Hugh jumps from the topic of hurt to the topic of hunting in an attempt to recreate that manly space in which talk is supposed to come secondary to getting manly stuff done.

- Showing off about beating up another boy and exaggerating the extent of the other guy’s injuries.

DESIRE

On the surface, Hugh wants his mother to be there for him after school.

Underneath, Hugh needs his mother to be there for him emotionally. He is not ready for the responsibility to flip. He can’t be the stable, grown one. He needs her back, and not just to light the fire and bake him a pie.

In this particular story, he tries to persuade his older friend to come upstairs with him, because he is terrified his mother has tried to harm herself again, as she had done a year ago. Tension comes from the reality that Hugh cannot betray the extent of his fear to another boy. This goes against the unwritten rules of nascent manhood.

In this episode of Talk Nerdy, Cara chats with Angela Garbes, author of Like a Mother: A Feminist Journey through the Science and Culture of Pregnancy. Angela tells Cara about her own experiences as a writer and a mother, including the ways women lack pre- and postnatal support in American society.

Motherhood w/ Angela Garbes

OPPONENT

Hugh’s friend is a kind soul, and it’s heart-warming to see two boys who are friends supporting each other. At the same time, Hugh feels pressure to look manly in front of John. McCullers made sure to create John two years older and with plenty of social prestige. The boys who are most concerned about the rules of masculinity are the ones who are not the most academic and sporty. If these two were peers of the same age, the relationship shown here would be less likely. John takes on a big brother role.

Hugh isn’t at the point where he really knows the depth of his pain. He tries to tell John what’s bothering him, and why he’s so upset his mother isn’t home to greet him, without so much as a note. He confides to John that his mother was sent to the hospital, associated with mental illness and therefore highly stigmatised. John responds beautifully, saying that could happen to anyone.

But where Hugh falls short is in asking his friend to stay with him because he’s terrified. That is a bridge too far. John thereby leaves to sell tickets when Hugh really needs him the most. John ultimately lets him down by rejecting his poetry, and by accidentally using the word ‘crazy’. He has absorbed the rules of masculinity to the point where he can only offer Hugh a practical solution to the problem of his missing mother: Get a television. TV means your house will never be quiet. Hugh does not want a practical solution from his friend. He needs realness and continued company against the terror.

He hated John, as you hate people you have to need so badly.

“The Haunted Boy”

John correctly guesses that there’s something upstairs that terrifies Hugh. This is the moment where readers really want Hugh to tell John the extent of his anxiety. It is heart-breaking when he cannot.

The bigger opponent in this story is patriarchy, which forces adolescent boys to become a certain type of masculine or else face demotion down the gender hierarchy. Hugh’s father cried on the way home from the hospital, but suppressed his emotion by drinking and withdrawing completely from his own son, who was required to eat alone. Instead, Hugh seeks what little emotional care he can from the nearest woman, because men are not permitted to care for each other, even for their own sons. Hugh must get anything he can from the “old maid” Mrs Richards who lives next door, and who watches “old maid shows” on TV.

PLAN

We find out after John leaves (to sell tickets for a fundraiser — a ticking clock device), that Hugh has thought all along that his mother could be dead upstairs. He has planned to check on her.

Readers can deduce that he wanted John to hang around so that he’d at least have support if he went upstairs and discovered the worst.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Hugh does not find his mother upstairs. He lies on her bed and bawls his eyes out. At this point Carson McCullers dilates the pacing by telling us that “he did not cry”, which McCullers uses thirteen times, bringing pacing to a standstill.

By brining pacing to a standstill, Hugh is forced to confront his darkest emotions. He experiences catharsis.

CATHARSIS: the process of releasing, and thereby providing relief from, strong or repressed emotions. Catharsis is a subcategory of anagnorisis in which the audience empathises so keenly with the main character that they consciously or subconsciously connect the emotions to their own lives, feeling what the character feels. Removed by the filter of fiction, this can be revelatory and healing.

ANAGNORISIS

McCullers did not always tie their stories up hermeneutically at the end, but in “The Haunted Boy,” the plot is tied up when readers learn, alongside Hugh, that his mother simply went shopping for new clothes. She hadn’t left the house to go shopping in over a year (mostly because she was in hospital). The symbolic weather “the first warm day” is revealed to be of practical story relevance, as well as symbolic relevance. (Hugh’s mother needs summer clothes.)

Wouldn’t it be nice if Hugh learned it’s fine not to be strong all the time? Hugh’s father almost gets there, just as Hugh almost got there in explaining the depths of his fear to his best friend. Ultimately, though, Hugh’s father respects his son precisely because he’s held himself together all this time. The expectation after this afternoon is that Hugh will gather his emotions in a tidy bundle and continue stoically as before.

NEW SITUATION

The only person Hugh was really able to show himself to is his own mother, who saw him break down, and who understood his outburst of anger was actually fear (the only difficult emotion allowed in Real Men TM). Hugh felt safe revealing his true thoughts about his mother’s clothing — revealing that he can admire pretty, feminine things as he secretly admired the colourful flowers in the front yard.

Hugh’s father tells him, “Nobody can be nervous before they are sixteen years old. You have a long way to go.”

At first this seems a minimising thing for the father to say. What does he really mean? “You’re still a boy. You’re allowed to cry. But when you’re the age of a man, you’ll be expected to contain emotion like a man.”

Notice, too, that the father uses the word ‘slip’ then changes it to ‘petticoat’. The father’s dialogue highlights the double meaning of ‘slip’, in case we missed it.

One sure fire way to elicit emotion in readers: One character who is normally reserved and withholding, shows kindness to another character. McCullers demonstrates the power of that trick here, when the father, who has deftly been portrayed as a 1950s stoic sort of man, tells his son that he is proud.

He knew that something was finished; the terror was far from him now, also the anger that had bounced with love, the dread and guilt. Although he felt he would never cry again — or at least not until he was sixteen — in the brightness of his tears glistened the safe, lighted kitchen, now that he was no longer a haunted boy, now that he was glad somehow, and not afraid.

“The Haunted Boy”

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

From now on, we can expect Hugh will save his most vulnerable self for himself alone, or perhaps for his girlfriend and wife later on. If he’s lucky, the women in his life will continue to perform the emotional labour of recognising Hugh’s real emotions, because it is not permitted for men to share in these rituals.

Why is Hugh standing alone, but bolstered, in his back yard? I believe Hugh’s father is guiding his son towards the expected version of masculinity, the only one permitted in the 1950s, which is this: You will eventually be all alone with your emotions, son, but that’s all right because so long as you conform to the rules of masculinity, that privilege will compensate.

RESONANCE

Although this is a story from the 1950s, nothing feels old-fashioned except perhaps for the idealised housewife whose main job in life is to be there for her husband and children. Change the setting just a little and the relationship between these boys feels relatable. Rules around masculinity have unfortunately not changed in step with the women’s liberation movement.♦