Harvey Slumfenburger’s Christmas Present (1993) is a picture book written and illustrated by British storyteller John Burningham. The pacing in this story is a little different to most picture books seen in bookstores today. The word count is higher than 300-400 words. There’s a reason for this. The cumulative nature of this narrative feels designed to lull excited children to sleep on Christmas Eve.

I know it’s a hugely controversial thing to say that some reading material is designed to lull children to sleep. After all, shouldn’t reading be fun and exciting at all times, to hook kids on reading? I don’t think this is the case in reality. Some books are writtten to soothe and calm. Also, I feel there is a time and a place for lulling children to sleep. I suspect this story can do the trick nicely. Also, kids seem to have a much higher tolerance for repeating scenes than I do; it is in fact myself who starts yawning uncontrollably while reading some stories structured like this one. (Also, I suspect some kids will be riled up by the excitement of what’s in Harvey’s present.)

SETTING OF HARRY SLUMFENBERGER’S CHRISTMAS PRESENT

The setting of this story is clearly a Northern Hemisphere one, which is probably only noteworthy to those of us in the Southern Hemisphere. Unlike many modern Santa stories, this one lives in a small house on his own. He doesn’t have a wife, and he’s not surrounded by elves. I feel a little uncomfortable with the ‘surrounded by elves’ narrative myself, because it feels like a cosification of factory worker life.

For the purposes of this particular story, I feel it’s important Santa lives alone, because this gives him something in common with the child, Harvey, who lives (seemingly) alone at the top of a mountain, with a similarly Spartan bedroom.

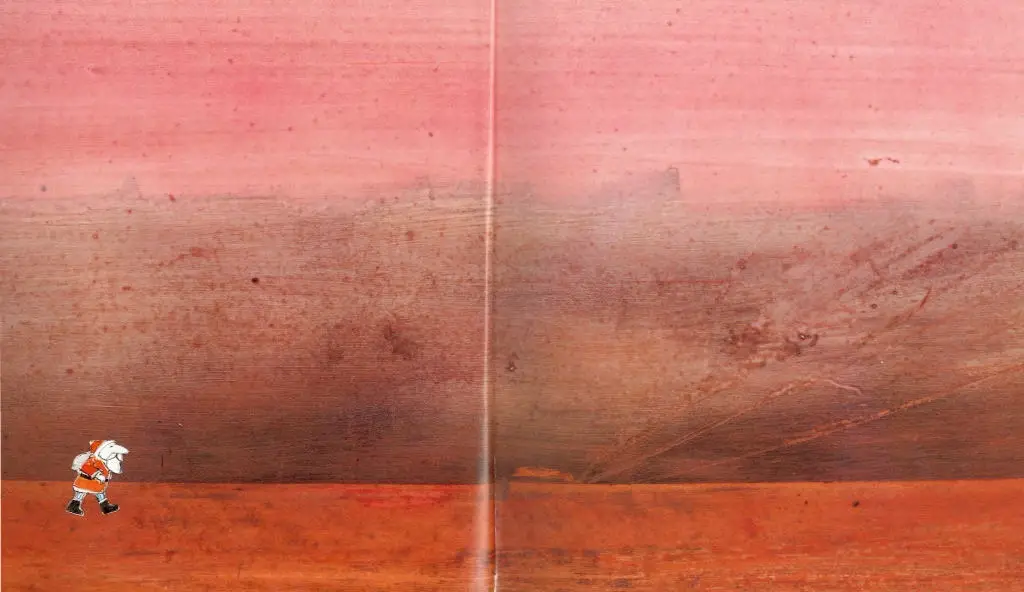

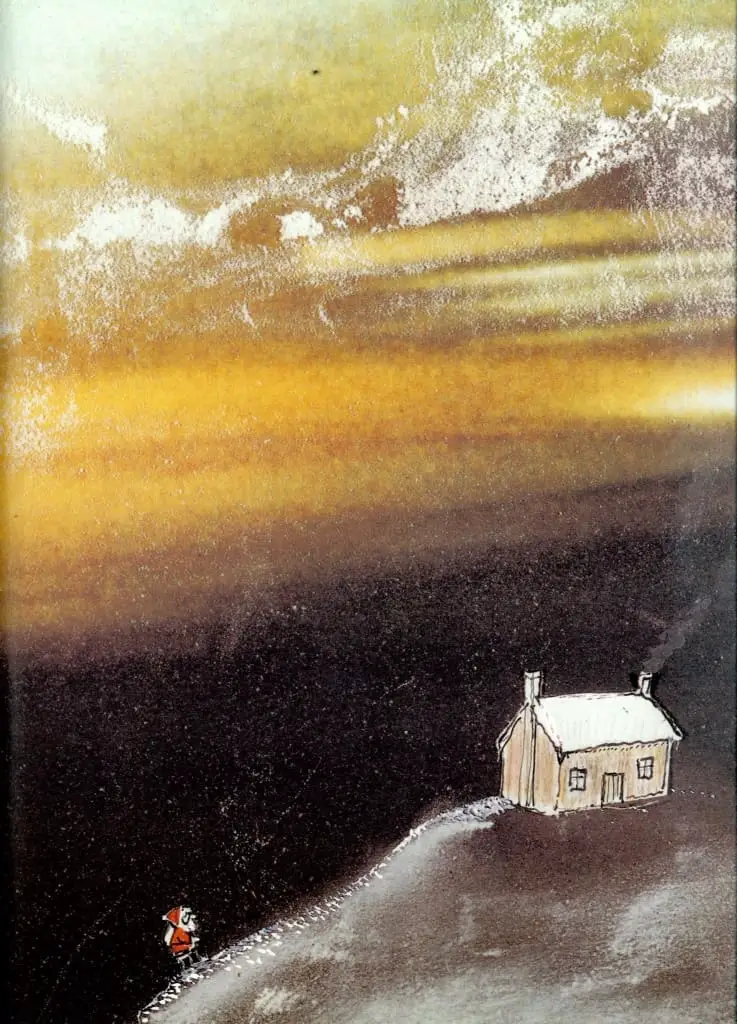

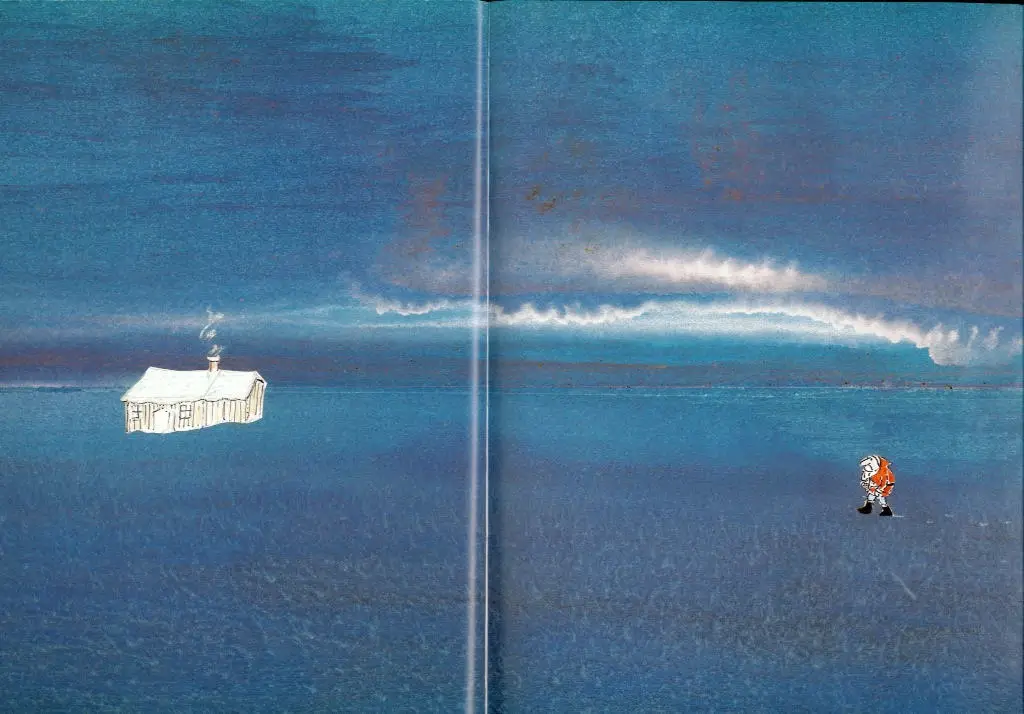

Burningham makes use of a Ticking Clock device in this story, using only colour. He changes the colour of the sky to show us that morning is approaching.

STORY STRUCTURE OF HARVEY SLUMFENBERGER’S CHRISTMAS PRESENT

PARATEXT

Santa finds a forgotten present — and is determined to deliver it himself.

MARKETING COPY

One Christmas Eve after the reindeer are asleep, Santa sees a present still in the sack — Harvey Slumfenburger’s present. And so he starts a very long journey on foot . . . by plane . . . on skis . . . and so on until he reaches Harvey’s hut, slides down the chimney, and delivers the last Christmas present, safe and sound.

SHORTCOMING

The name ‘Slumfenberger’ feels like something out of an Edward Gorey story. Despite his enticingly weird name, the viewpoint character of Harry Slumfenberger’s Christmas Present is Santa, whose mission is delivering a present to this economically deprived boy. Burningham ups the stakes by telling us that this is the only Christmas present Harry will be getting, as usual.

According to much folklore, Santa has the benefit of magical flying reindeer, which reassures children that they won’t be going without their loot. However, some stories are all about the difficulties of getting presents to every single child (as the story goes), and stories like these serve to reinforce the story that Santa manages to get to every child, precisely by showing the difficulties he faces. Kids don’t seem to buy that it’s easy to get presents delivered, but until a certain stage of development they seem to accept that, with difficulty, it can happen.

To write a good Christmas Night narrative, sometimes a storyteller has to do something to rid the world of the magic which is meant to make everything run smoothly. In this story, Burningham gets those magical flying reindeer (cosily) out of the way by telling us the reindeer are very tired and one of them is coming down with something. Santa must deliver one forgotten present without the aid of his magical flying reindeer.

DESIRE

Now that Burningham has told us that Harvey Slumfenberger will only be getting this one single present, the audience empathises, and really, really wants the present to get there. The reader equals Santa, but also the boy.

OPPONENT

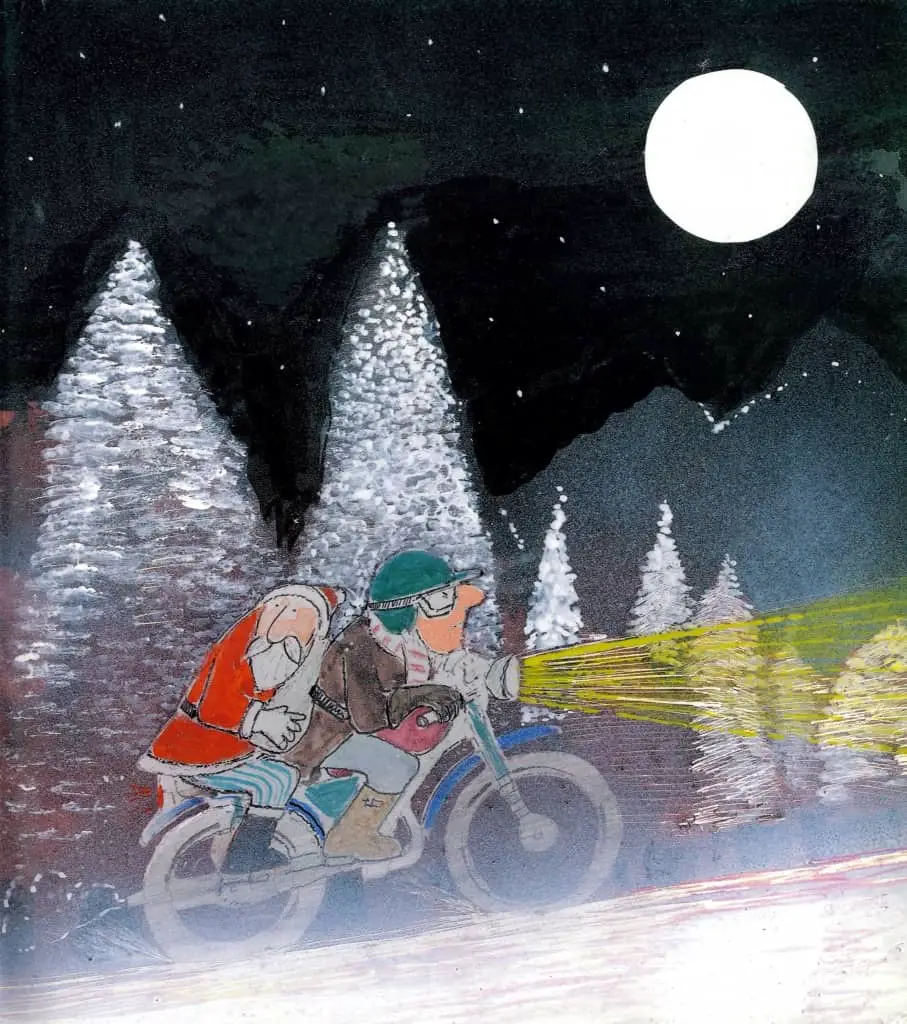

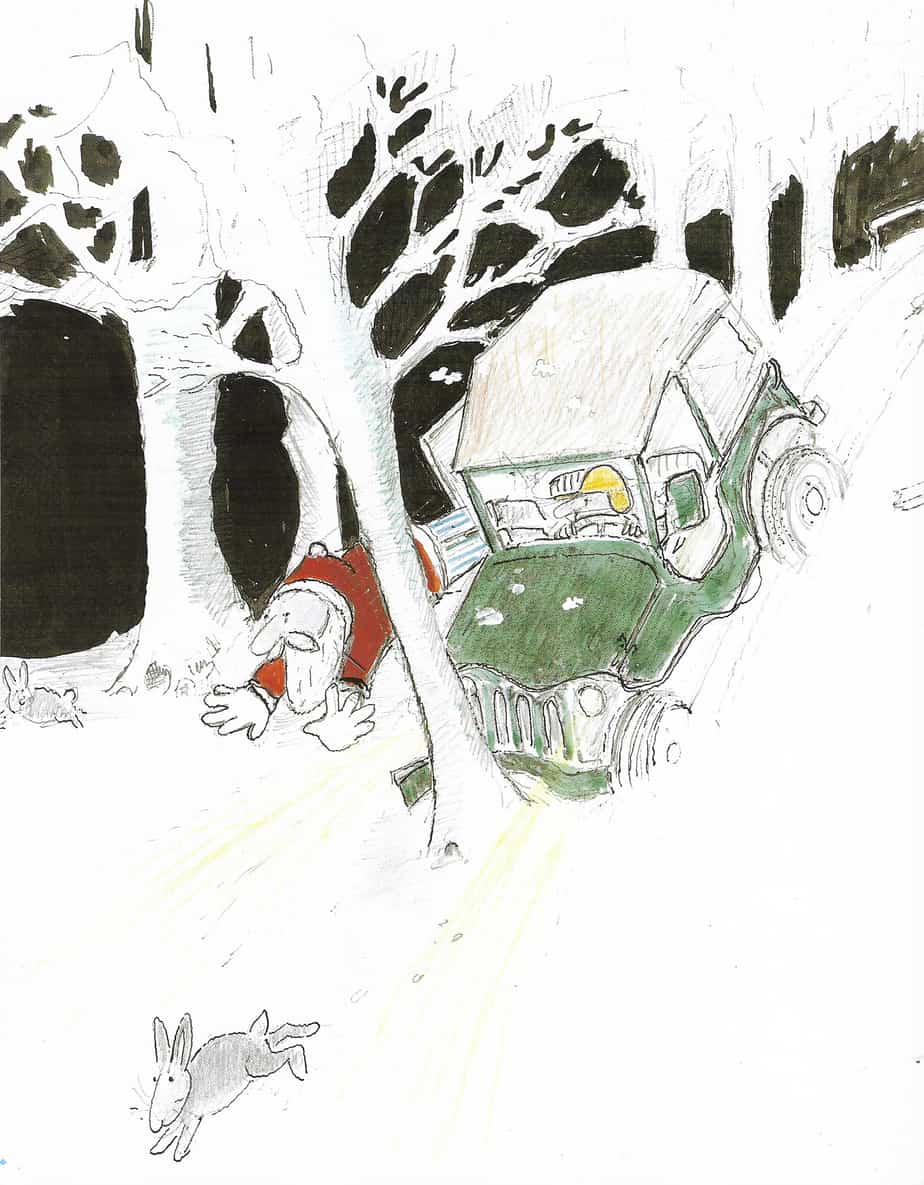

In a mythic journey such as this one, Santa would normally meet a mixture of allies and opponents. In a cosy children’s stories, allies tend to outnumber the opponents. In this story, too, there are no human opponents; everyone who tries to help Santa reach Harvey’s house is foiled by nature or broken equipment.

PLAN

The plan is simple, or should be: Take this present to Harvey Slumfenberger. Unfortunately he lives at the top of a mountain (called Roly Poly Mountain, I guess because it’s easy to roll all the way down it).

THE BIG STRUGGLE

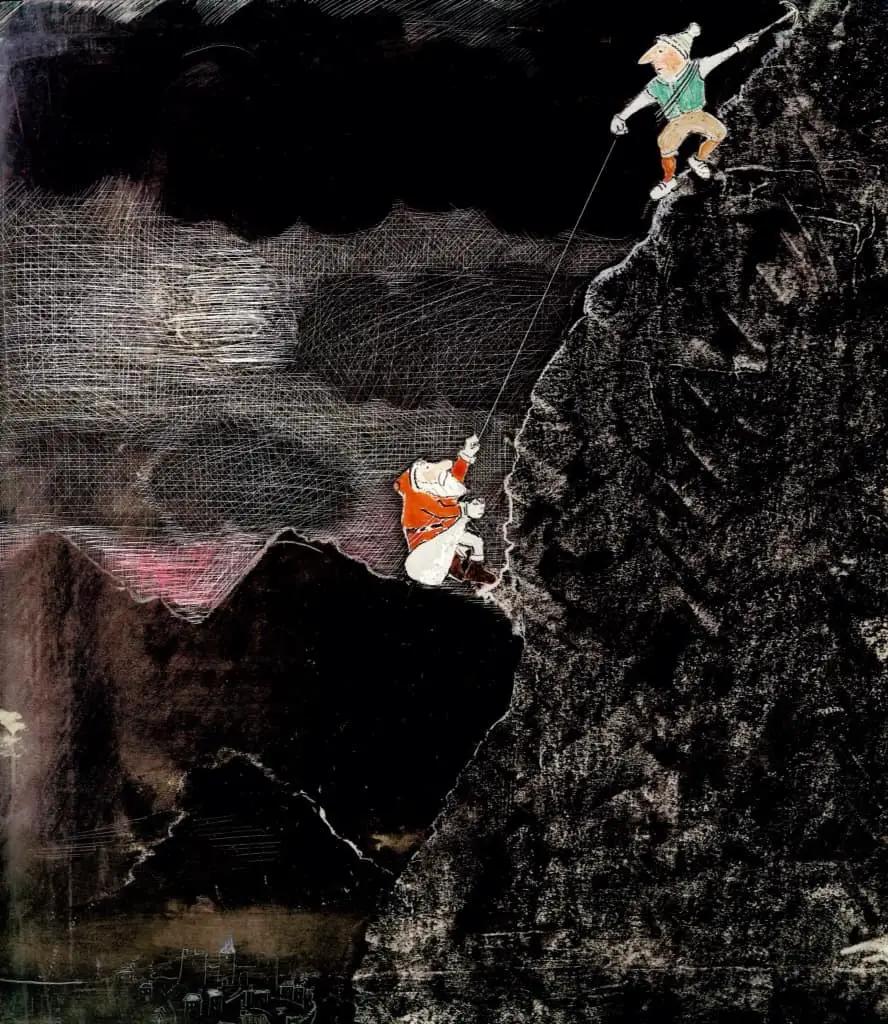

Burningham’s double page spreads full of sky and earth emphasise the smallness of the characters, and how helpless they are against nature. This illustration with its black sky and rocks shows the ‘near death’ battle Santa has against nature.

ANAGNORISIS

We expected this all along, but eventually we all learn that Harvey will safely be getting his Christmas present.

Now Burningham would’ve faced a bit of a narrative challenge: If it was so hard for Santa to get to Harvey Slumfenberger’s house, how to get him home? The mission has been accomplished; the reader does not want to see Santa go through all that rigmarole again.

There’s a good way to quicken the pace and compress time in picture books: montages. A double-page spread of montages shows all the wacky ways Santa finds his way home again. Because he is going down a mountain rather than up it, the mode of transport is different e.g. the flying fox (or zip-line, as I’ve heard it called outside Australasia).

We don’t know where he gets that hot air balloon from, or the skates. It doesn’t matter.

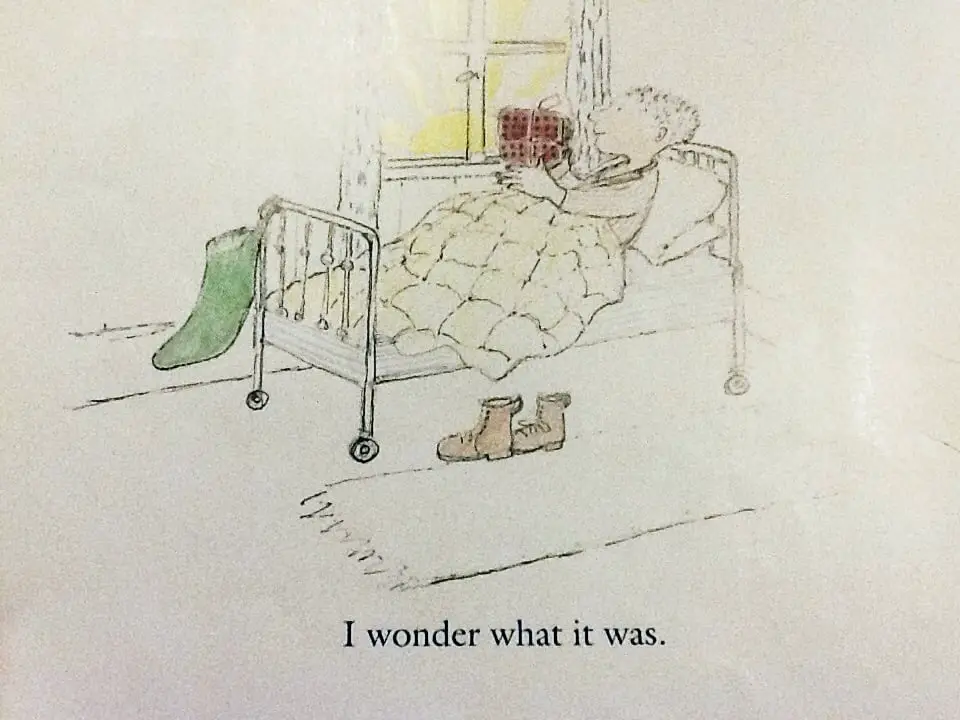

NEW SITUATION

Santa delivers the present and returns home. Burningham could have chosen to end the story there, but the viewpoint switches to that of Harvey, and we are left with Harvey about to open his Christmas present. The narrative ends with a question, “I wonder what it was.”

The young reader is invited to join in with Harvey’s excitement.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Teachers read this book in the classroom to talk about the value of the inidivual, or what other cultures from ours may call ‘individualism’. If Santa will go to these lengths to deliver a single present to a single boy, we must all be important. This explains the uniquieness of Harvey Slumfenberger’s name.

For younger children, what was inside the present? Re-read the picture book and it’s not a matter of finding the clues; the contents of the present are entirely left to the imaginations of the reader. In this way, the reader contributes to the story, and the story becomes tailored to individual children, as everyone wants something different. (Popular toys aside.)

RESONANCE

The Santa story of delivering presents shows no sign of ending anytime soon, but it will be interesting to see whether this generation of Western children continue it with their own offspring. There may be a flip away from consumerism at some point as our children live with the climate crisis.