Dogs commonly feature in pet-death stories. Probably because goldfish are bastards.

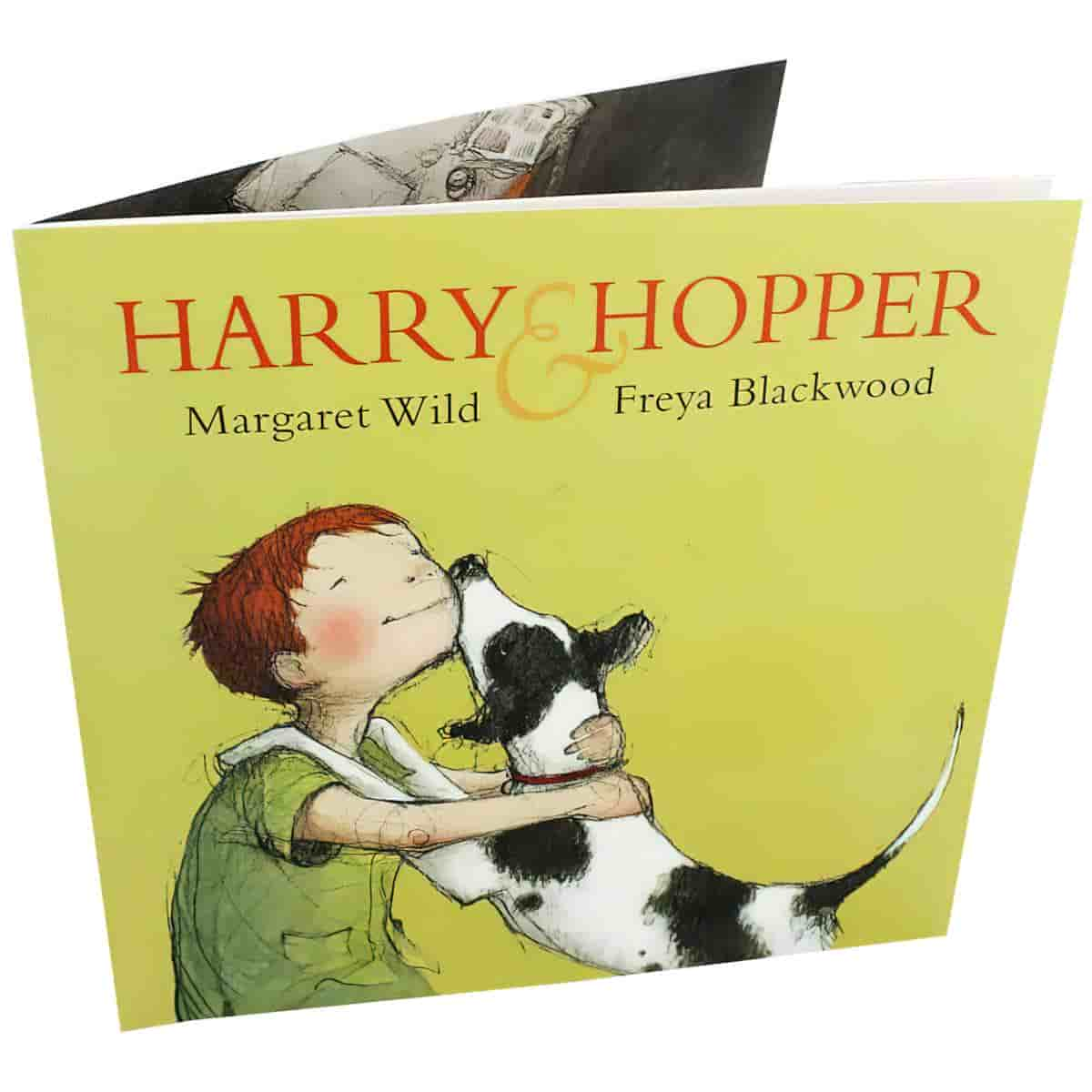

WHAT HAPPENS IN THE STORY

A boy’s best dog friend dies while he is at school. Harry comes to terms with Hopper’s absence gradually, first by trying to distract himself and not think about Hopper at all, then by imagining his reappearance, and finally by imagining saying goodbye in person.

Question: why, in nearly every book for children about death, is it a dog that dies?

Goodreads review

Though as the NYT wrote, tearjerkers featuring dogs aren’t really all that common in the picturebook category. You’re probably thinking of chapter books.

Tearjerkers are a fixture in the dog book genre, but they are perhaps less prevalent in the kiddie division, which makes this enormously affecting Australian import so distinctive.

New York Times

Naturally, any children’s book about death is going to garner a variety of responses from adult readers, because readers all have their own ideas about death and children. Some people don’t like supernatural storylines, preferring not to stimulate children’s hopes that death is not really final. Others prefer religious explanations. Some thing that death must be introduced very, very gently to children while others probably don’t think books about death are appropriate at all.

I also didn’t like how they just jumped straight to “Hopper is dead”. The dad has “tears in his eyes” but I guess he just manned up. The dad doesn’t offer any comfort. Just “Would you like to come and say good-bye to Hopper before I bury him?”

No “it’s okay, Hopper is in a better place”, or “remember the good times” is is just he is dead…lets bury him.

Goodreads review

Here is the part about the dog ‘coming back to life’:

“In the middle of the night,

something woke him up.

He turned over—-and there,

leaping at the window, was a

dog. A dog as jumpy as

a grasshopper!Harry sprang off the sofa and

ran to the back door. He flung

it open.‘Hopper!’ he cried. ‘You’ve

Harry and Hopper

come back!’”

In another book about the death of a pet, Goodbye Mog by Judith Kerr, it is clear from the pictures that Mog is not really there but just a sort of ghost. This is because Kerr depicted the dead Mog by drawing more lightly with her pencil and choosing lighter colours. But in this book, there are no clues about dream sequences/imagined parts. When Hopper comes back, it’s really as if he has come back.

I was uncomfortable with the fact that the story and illustrations made the dreams all too real. This may give readers false hope of seeing their loved ones every time they go to sleep.

Will some kids be confused by the appearance of Hopper after he has been buried? Will they think he’s a ghost? Maybe. Not sure. It’s certainly possible.

It’s not clear from the story whether Harry’s encounters with Hopper are dreams or something more fantastical or supernatural

Goodreads reviews

WONDERFULNESS

For parents who would want to present death in a no-nonsense fashion to their children, this is a very good choice.

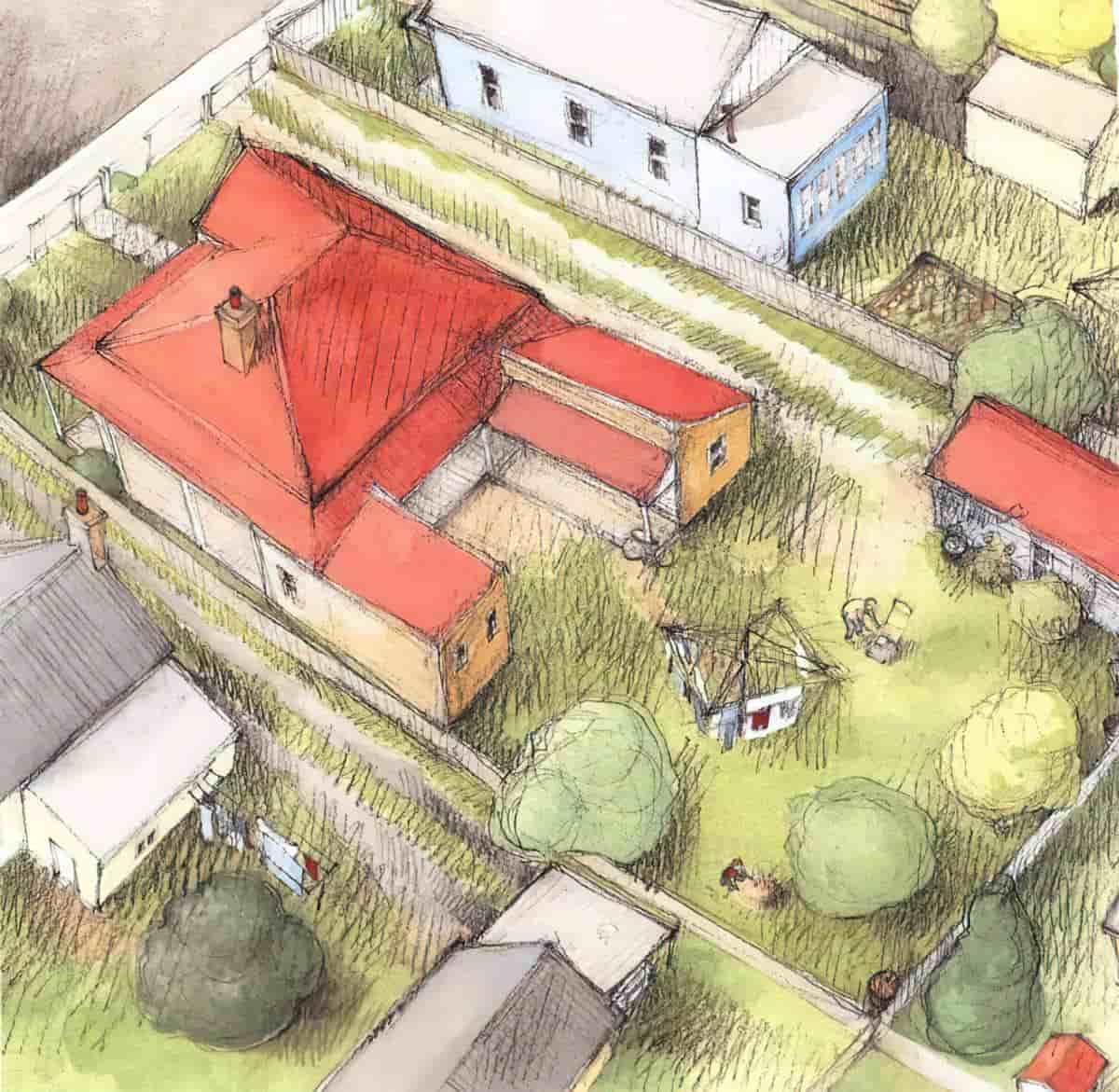

Interestingly, there is no mother in this story. We don’t know where she is, but she does not live with Harry and Dad. Presumably, Harry has already dealt with some earlier grief, in which case he knows what to do this time. The good thing about there being no mother is that we see dads doing domestic things, like hanging up washing on that Hill’s Hoist.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION

This is a story about a dog’s death, but we’re encouraged to think about the dog’s life as a whole from the first title page, in which we see a litter of puppies sitting upon the words ‘Harry and Hopper’. An especially cute puppy has separated himself from the squirming litter and offers his paw. On the second title page we see that Harry has been standing off-stage with his father, and Hopper is running towards him. The title page, of course, is where the story really starts in any picture book.

SKETCHY IS COMFORTING

Blackwood’s illustrations are done on watercolour paper with watercolour, gouache and charcoal. The grain shows through. Along with ‘messy sketches’, this means the illustrations are definitely ‘illustrations’ (rather than photos). How do you think a picture book about death would go down if children saw actual photos of a (staged) funeral? That would be the opposite extreme — picture books about death tend to be sketchy and arty, and I believe this helps remind young readers: Don’t worry, this is just a story.

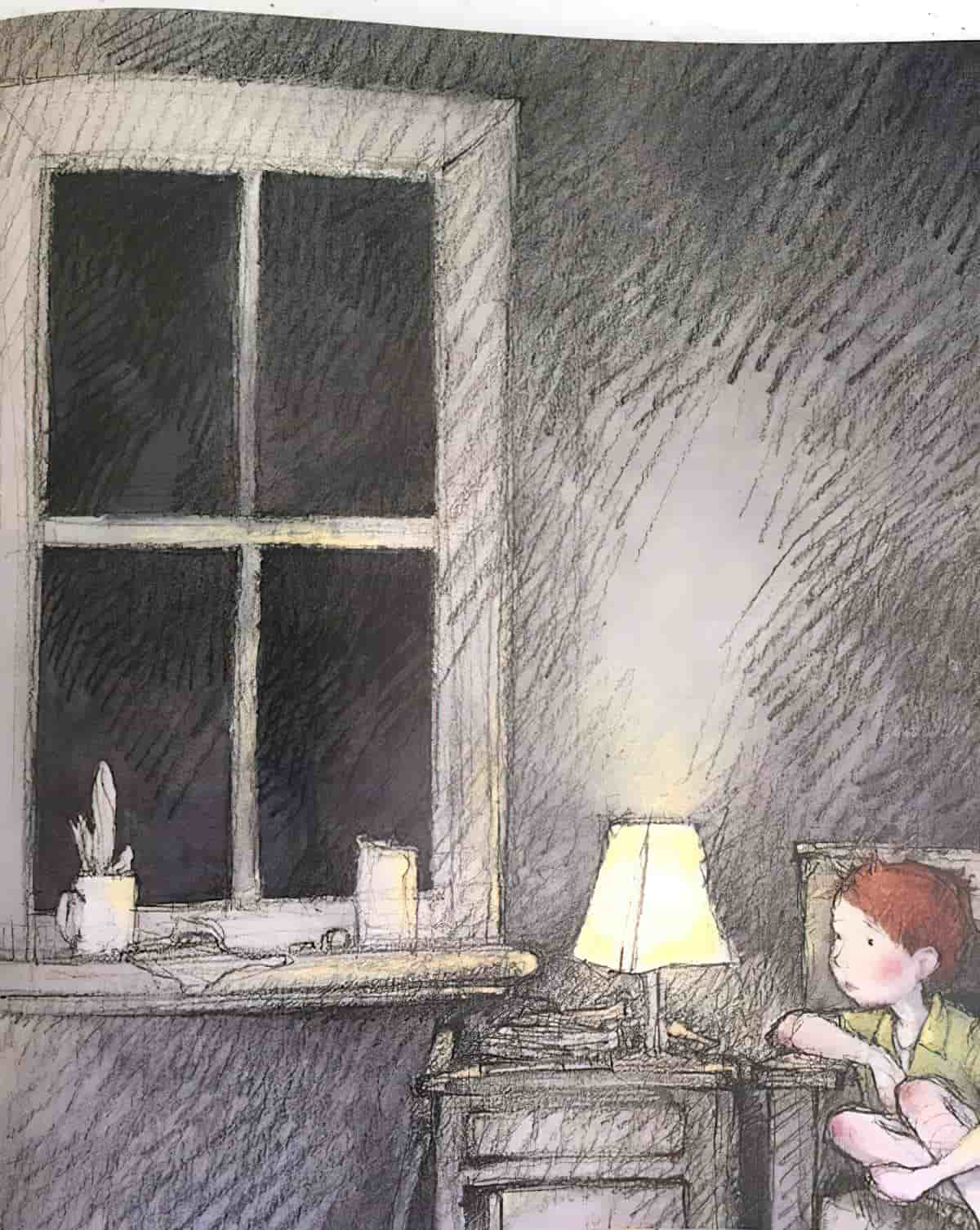

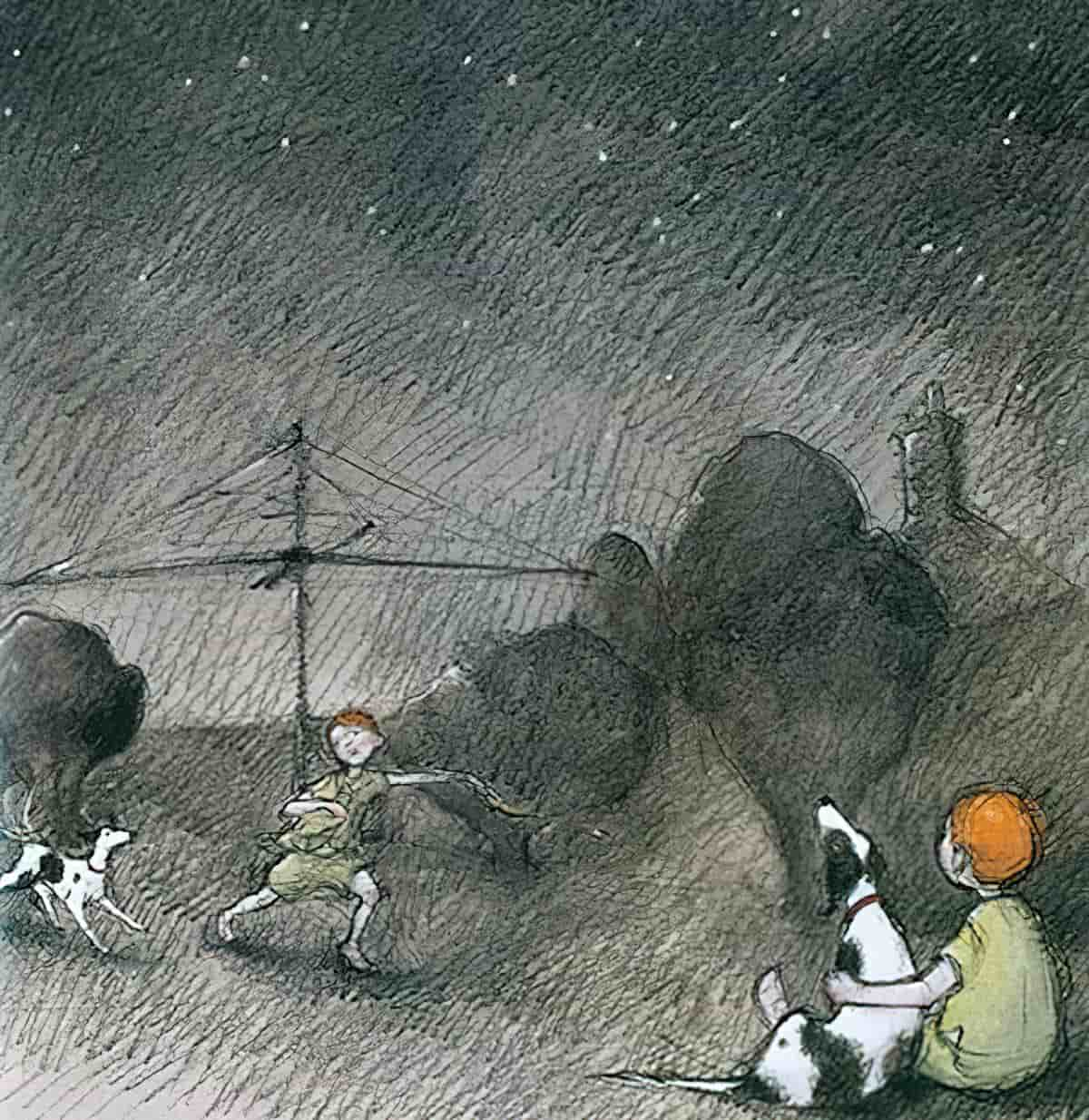

LIGHT AND DARK

If you’ve watched Six Feet Under or any number of other films about death, you’ll often notice a strong opposition between light and dark. Obviously these are symbols for life and death. Freya Blackwood has worked in film (Weta Workshops in NZ), and I think it shows.

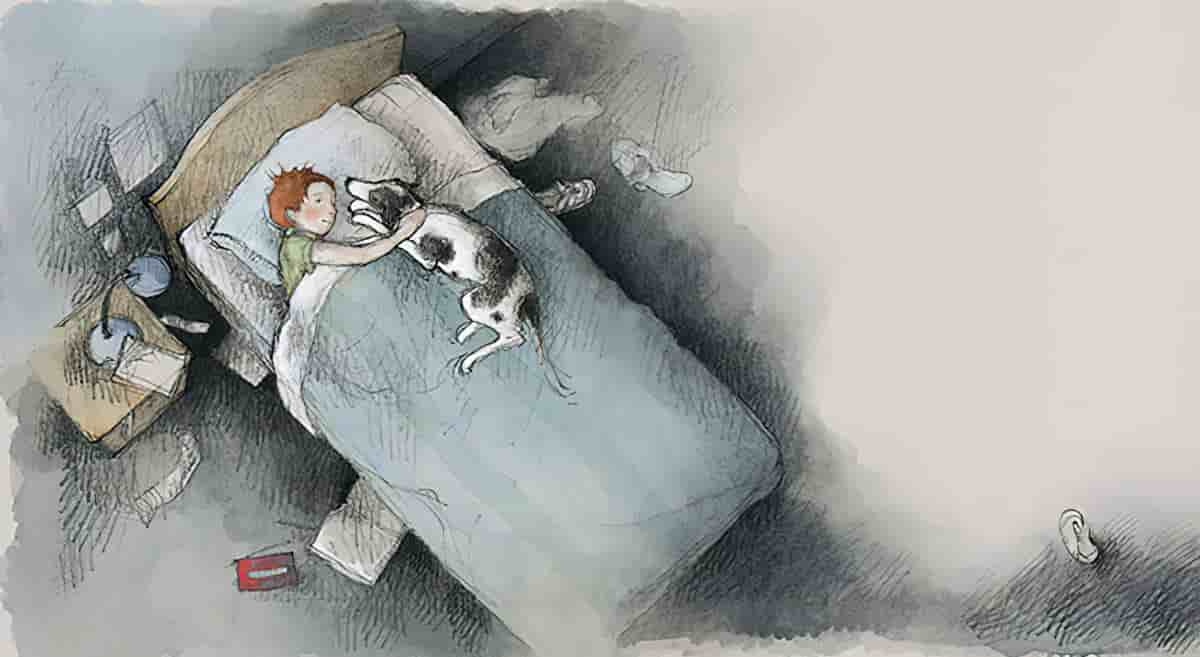

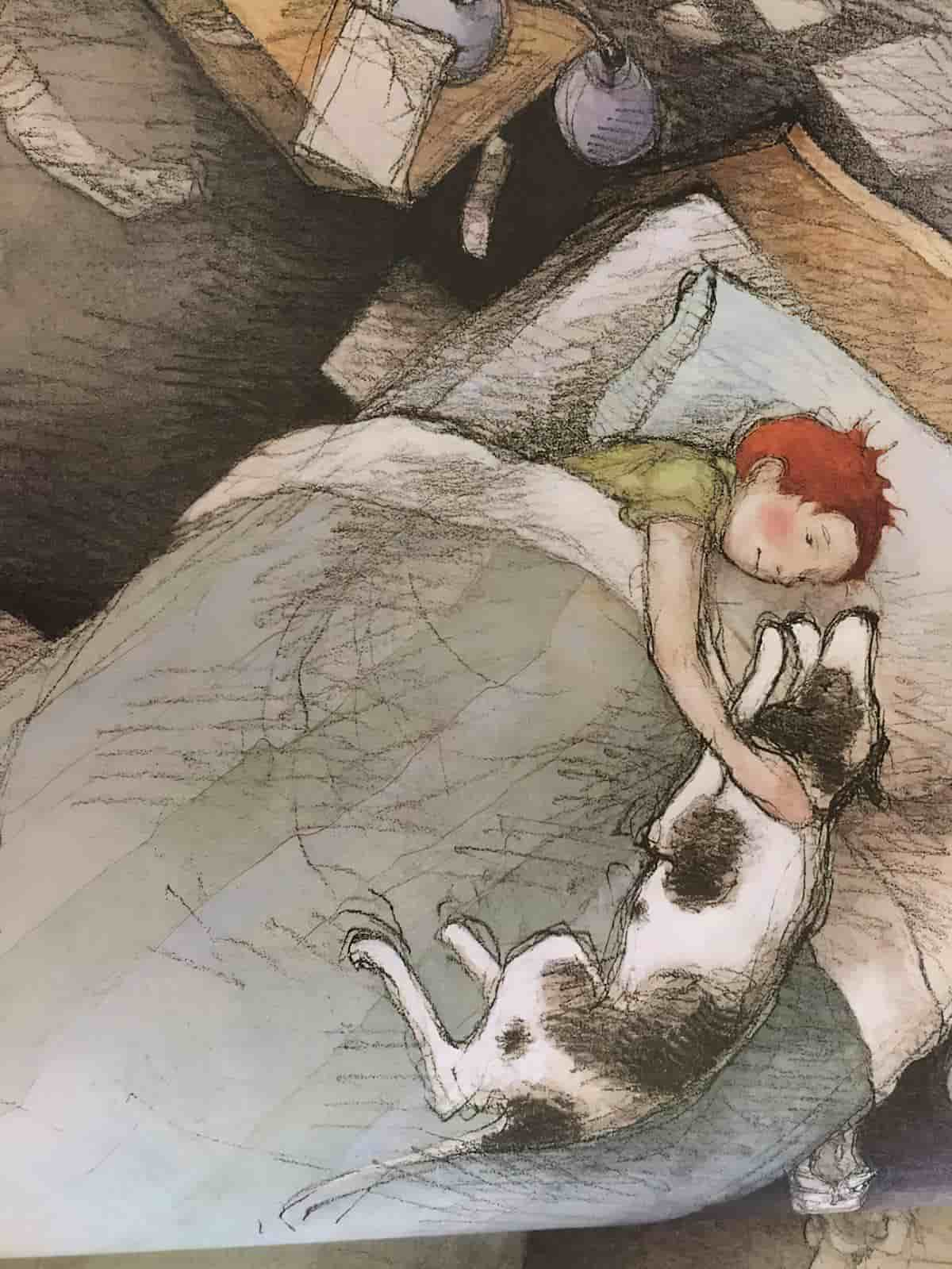

Through this story, too, there is a warm light in the darkness, often provided by Harry and Hopper themselves. Here we have a lamp shining against the wall, and as a halo across Harry’s head.

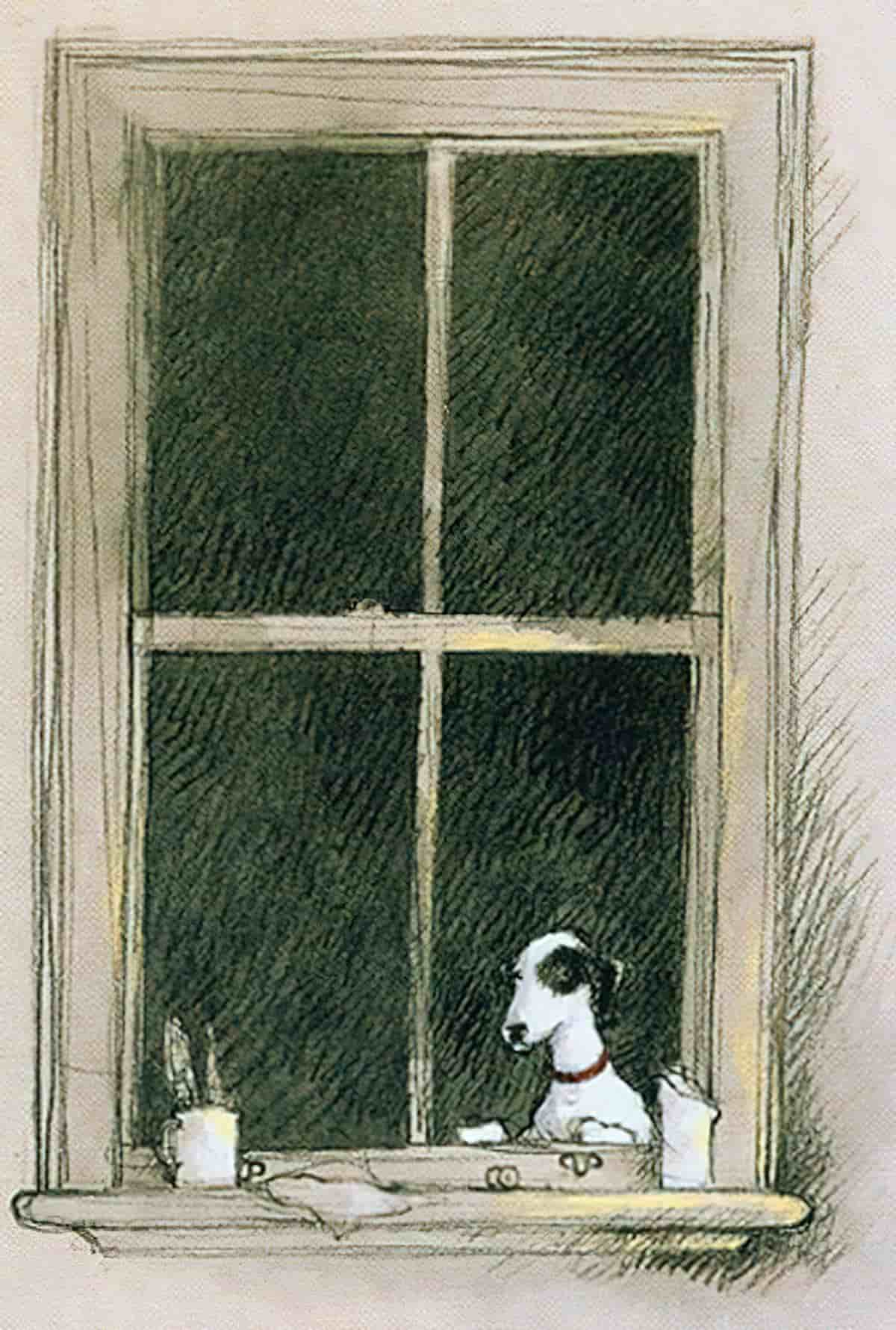

In the second illustration below, with dead Hopper peering through the window, the yellow light cast upon the sill serves to make the darkness/death of outside seem even darker.

AUSTRALIAN DISTINCTIVENESS

Freya Blackwood’s stories all seem to have a good balance between interior and outside scenes. Her children tend to live in the suburbs, and spend a lot of time outside. Here we have the Hill’s Hoist washing line — a detail that marks the story as distinctively Australian/NZ — I haven’t seen this kind of washing line illustrated outside this part of the world, but let me know if I’m wrong!

Artists such as Nigel Brown (NZ) have also turned the Hillman’s Hoist into a feature in their work. Brown did a whole series of them; this is ‘clothesline painting number five’.

Although I say this book is distinctively Australian, the illustrator chose not to put wide-brimmed hats on the boys who are sitting on a form bench eating their lunch, yet they’re in summer uniform, so I figure this might be set in an earlier time, perhaps in the 1980s. (There’s one of those old-style TVs in one of the pictures — no flat screens.) This generation of Australian school children have a ‘no hat no play’ thing going on, even if there’s a shade sail.

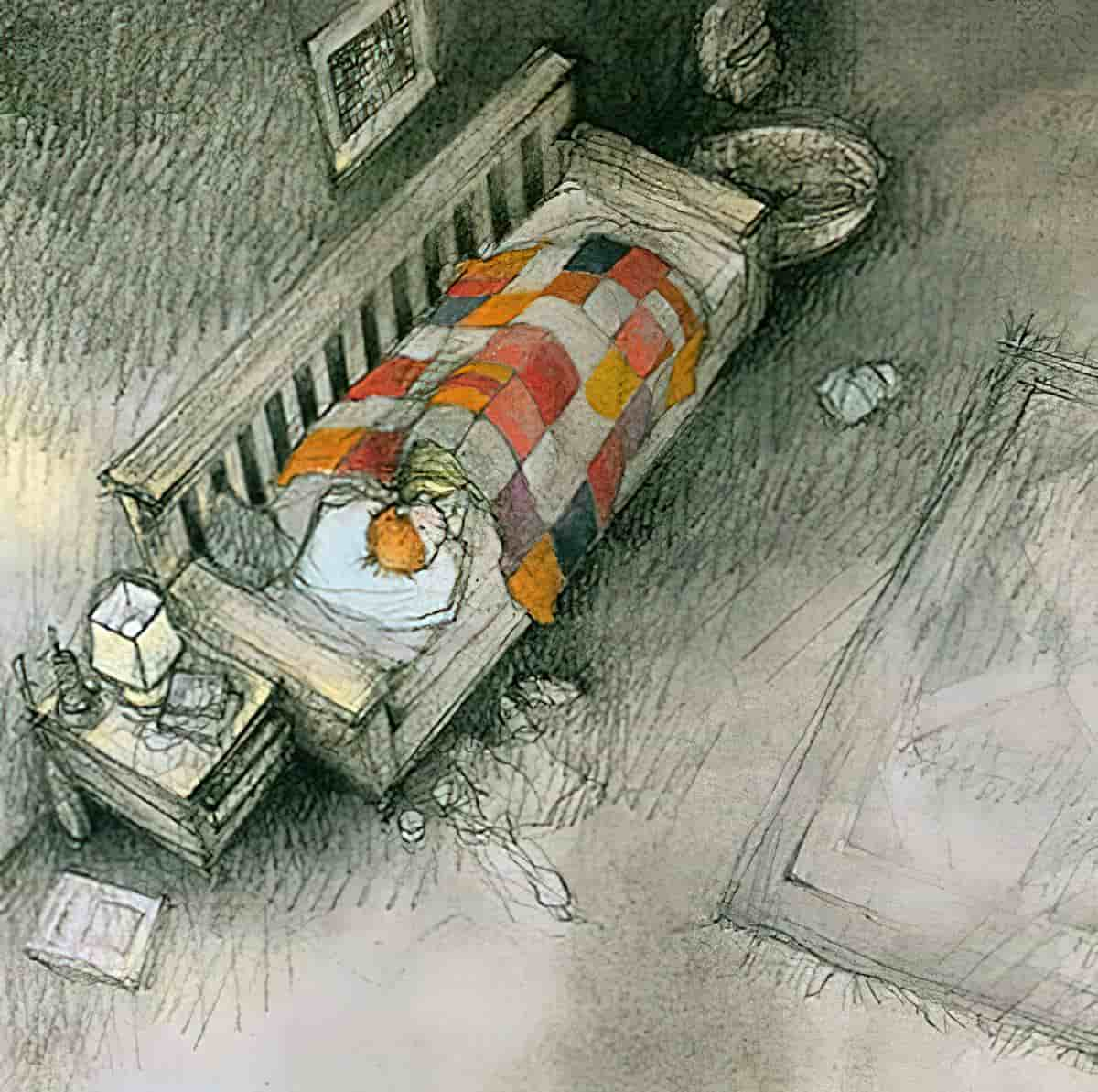

VARIED PERSPECTIVE

Freya Blackwood is particularly good at drawing from high (and low) angles, varying perspective constantly to create dramatic moods and add interest. (Apparently her parents were artist/architect — I’ve seen other outstanding perspective work from architecturally trained illustrators.) In order to draw like this you need to have a good understanding of perspective. I’ve been experimenting with cheating a little when creating illustrations from different angles by making mock ups in a 3D interior design program, then changing the perspective within the software and using that as a model. I believe Adobe makes it easier these days for illustrators using Photoshop and Illustrator to draw from varying perspectives too, by making use of the ‘vanishing point tool’. On the other hand, a lot of illustrators don’t want a photorealistic look at all, sometimes playing with perspective to make it look deliberately off-beat (as in the Nigel Brown painting above). Freya Blackwood’s illustrations are pretty much spot on when it comes to vanishing points and planes and all that, and because she’s illustrated in a loose, sketchy style, I’m impressed at the technical skills first and foremost.

One of the earliest picture books to vary perspective was an American book called The Story of Ferdinand by Munro Leaf and illustrated by Robert Lawson, published way back in 1936.

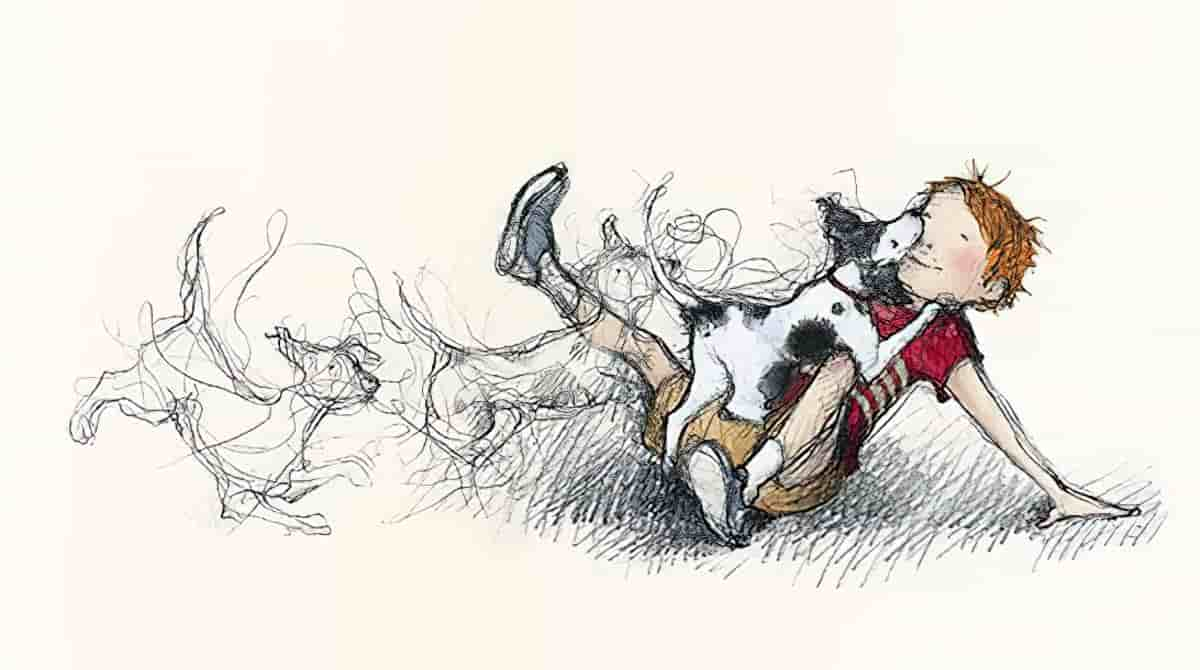

LINE TO SUGGEST MOVEMENT… AND SOMETHING ELSE?

Here’s an interesting technique: using loose pencil sketches uncoloured to suggest movement. In this particular story, this technique foreshadows something else: the ghost of the dead dog.

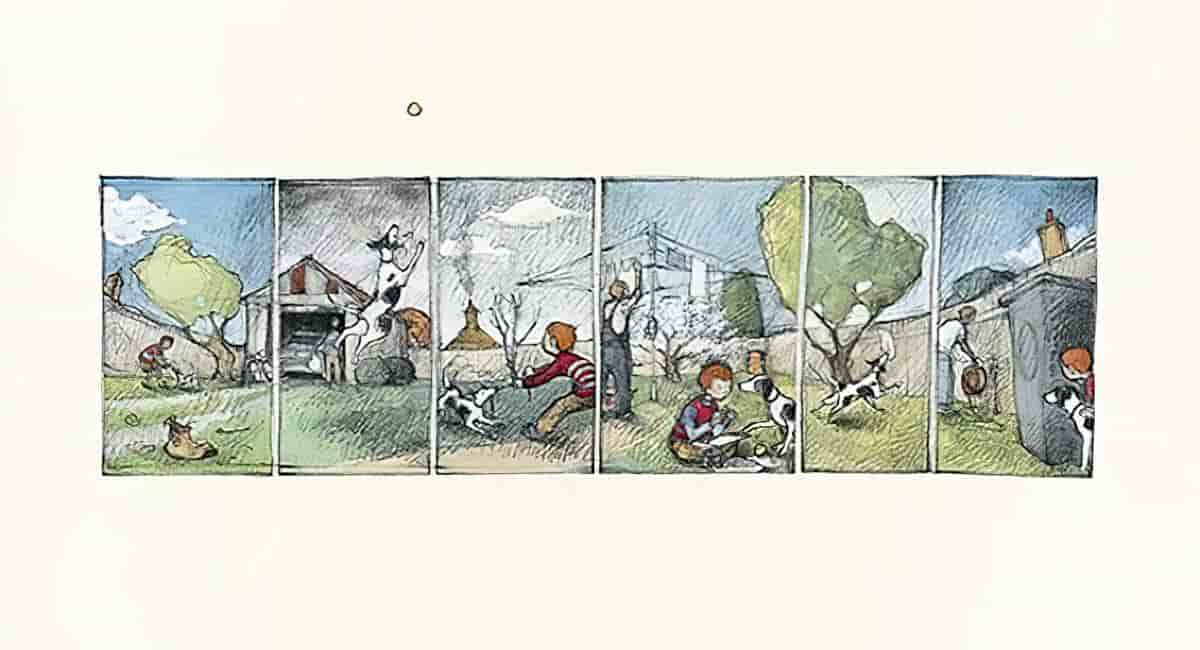

PANEL PAINTING

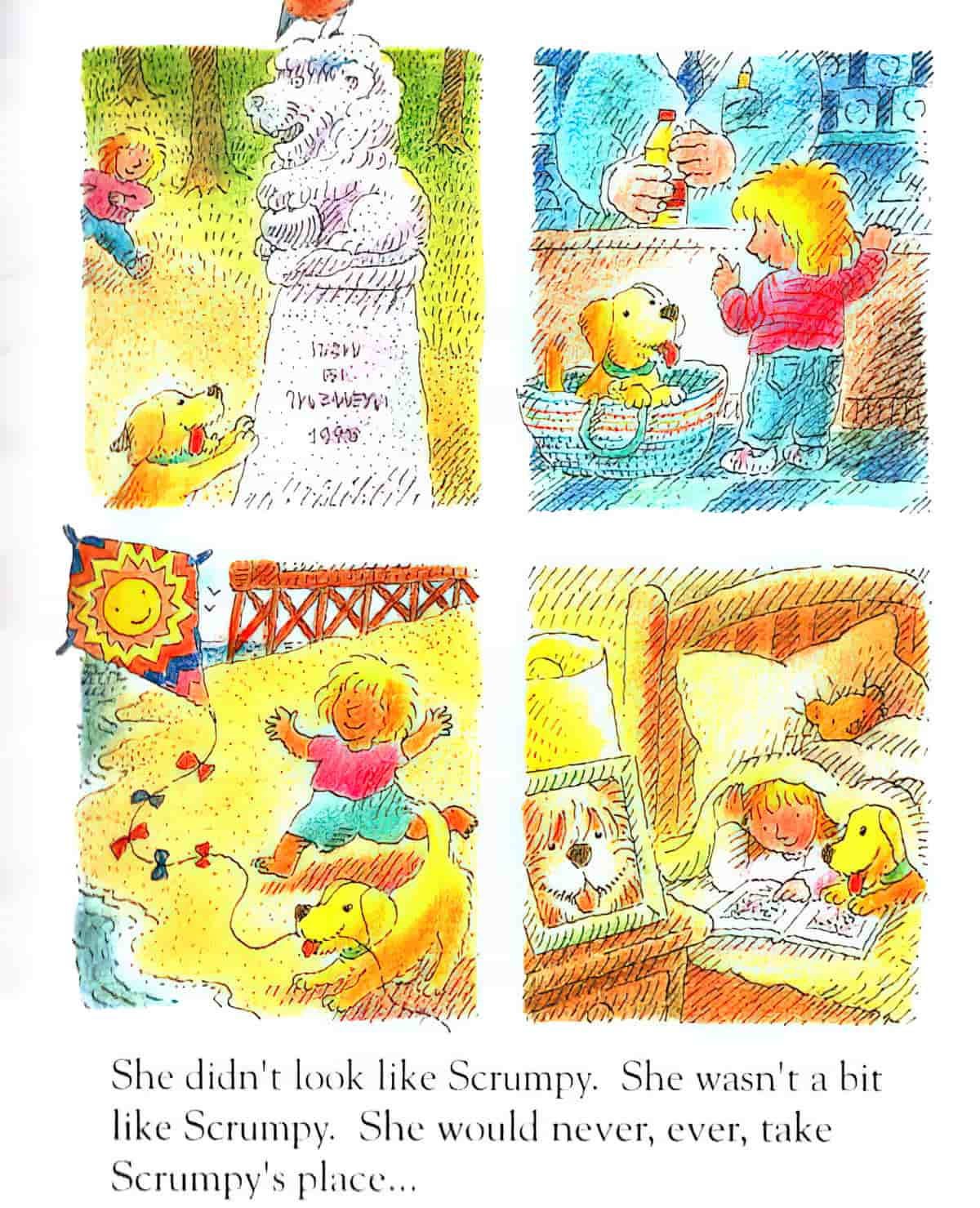

And here is another way of depicting movement, as well as the passing of time. If you go back far enough, you’ll find this technique on Greek vases, in which the viewer is meant to understand that there’s not five men walking in a line, but one man walking (or doing whatever). Children have to learn to decode such pictures; a very young child with little experience of picture books is likely to think that there are six dogs in the picture below rather than just a single dog depicted at different times. Such illustrations are technically called a ‘polyptych’. (Most commonly known perhaps is the triptych, with three panels.)

Traditionally, a polyptych has one central image and is surrounded by smaller ones, but getting away from the religious associations, modern illustrators of children’s books sometimes use this technique simply to present a lot of action in a short space of time (in the book).

Why might Blackwood portray a whole lot of information so succinctly? Because the story of a boy losing a beloved dog has been done before, so any new books of this sort must be a little different. You could argue that for a young reader what’s been done before is irrelevant, but picture books must appeal to the dual audience of adult and child, so the creators of this book wisely decided to dwell little on the relationship between the boy and the dog — the boy loves his dog, good, got it — and turn this story instead into one of a child dealing with grief rather than a story about wonderful child/pet relationships, of which there are even more.

ENDPAPERS

The endpapers of this book are brightly coloured squares. Assuming the design of endpapers is more than just decorative, what might these represent? They remind me a little of the colours of Elmer, from a completely different series of picture books. Some of the squares in these endpapers have a red line across the middle, like a street ‘do not enter’ sign. What to make of such bright endpapers?

If we look closely at the saturation and hue of the illustrations, the colours start bright, become muted as Harry enters his period of grief, then return to bright. The bright colours of these endpapers simply underscore the colour scheme within the story.

The illustration below is an example of one of the dark pages — it’s no accident that Hopper comes back to Harry at night (though the night can be drawn as brightly as the day, as observed by Vincent Van Gogh).

I’m sure there is a disproportionate number of red-headed children in picture books, and illustrations such as this one demonstrate why: The red hair serves as an attractive spot of colour to break up the darkness of the night.

STORY SPECS

Published 2009 by Omnibus Books (Scholastic).

Margaret Wild is a well-known Australian writer who has published more than 70 books.

Freya Blackwood has also illustrated books by writers such as Libby Gleeson, Margaret Wild, Roddy Doyle, Jan Ormerod, Nick Bland and Kyle Mewburn.

Blackwood said that being shortlisted for the {the CILIP Kate Greenaway medal for outstanding illustration] “was one of the most exciting moments of my life”. “Then to find out I won was really difficult to comprehend. I’d grown up with some of the [previous winners] and I still read the same books to my daughter now that my mum read to me. It was absolutely amazing,” she said. The Kate Greenaway medal has been won in the past by Shirley Hughes, Raymond Briggs and Quentin Blake.

“I don’t know if [Harry & Hopper] is my best book but I feel like the words and pictures go together very well,” added Blackwood.” I felt the connection when I read the story and it was one of the easiest to visualise and to illustrate. Very early on I knew what Harry & Hopper would look like, it seemed quite intuitive.”

The Guardian

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

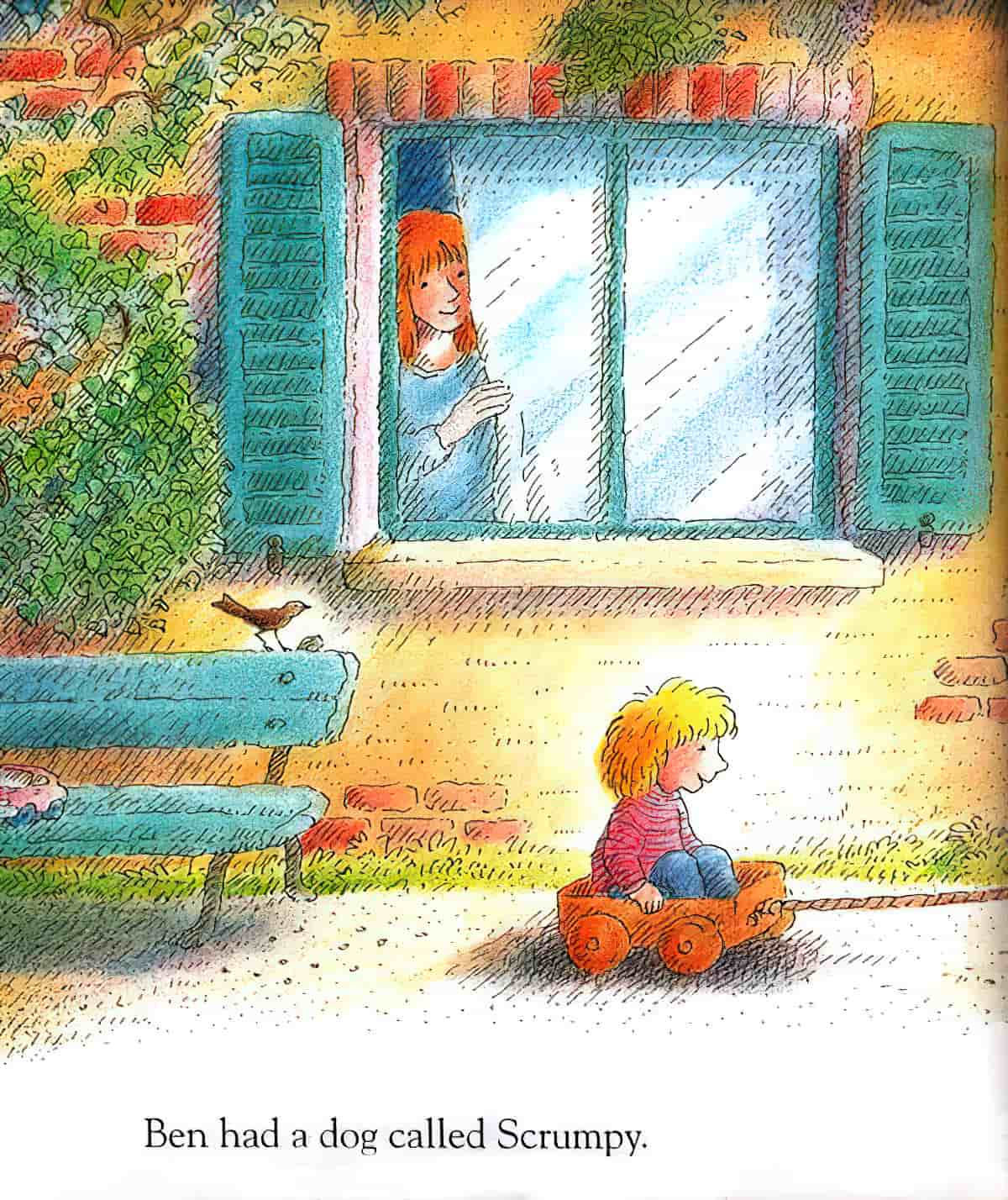

There are a number of picture books about a white boy whose dog dies. But too many of them end on an uplifting note with the replacement of the pet. One example is Scrumpy by Elizabeth Dale and Frederic Joos. The book opens like this:

At one point we think Ben is going to get a new cat, but our expectations are foiled; he gets a new dog. Female dog, this time. The author goes out of her way to impress upon the young reader that the new dog can never, ever replace Scrumpy.

I wonder which of her books Blackwood considers her best?

We might compare this book to some of the others she has illustrated and make a guess at it ourselves?

For more children’s books about grief, see some selections at Children’s Books Heal blog.

For me, the most moving death-of-a-pet story is actually a song, by Gotye.

Gotye wrote this song about some friends of his who were letting go of their 21-year-old dog, who was called Bronte. He has said, “You don’t have to necessarily interpret it as a relationship between people and animals. You can flip it on its head and turn it into a group of animals letting go of this peculiar relationship with a human child they have in the forest.”