Literary scholars today write about a type of plot known as The Harlot’s Progress. This is a narrative archetype — a type of story — which still gets written today, though in different form. In the 18th century the story of the ‘harlot’ who did immoral sex things for money then died would have been very familiar to anyone living in the West. The story was everywhere, in art, in literature, in newspapers, and in the way people talked about women.

Many of the following notes are from Chastity and Transgression in Women’s Writing 1792-1897: Interrupting the Harlot’s Progress by Roxanne Eberle, 2002.

WHERE DID THE NAME “HARLOT’S PROGRESS” COME FROM?

The narrative of women punished for sex work goes back further than this, but “Harlot’s Progress” is a series of six paintings by William Hogarth, painted in 1731. He was riffing on The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan. Hogarth did the engravings over following year. His paintings have been destroyed but the engravings still exist.

In the first plate, an old woman tells a young woman, Moll Hackabout, that she’s beautiful and that she might consider sex work.

In the second plate Moll has two lovers. She then becomes a mistress and finally a sex worker. She is arrested and sent to prison. Then, at age 23, Moll dies from a sexually transmitted disease. All six plates can be viewed at full size over at Wikipedia.

THE HARLOT’S PROGRESS IN LITERATURE

The narrative of the harlot who comes to grief can be seen across English literature of the 18th century, as well as in these famous images. This archetype is not only applied to women who become sex workers, but is used as a moralistic tale to control the sex lives of women across the board. anxieties about women’s autonomy in the Victorian period were in reality concerns about transgressive sexual selection. The publication of Darwin’s Descent of Man (1871) may have had something to do with these anxieties, as evolutionary theory doesn’t justify a gender hierarchy.

Although Moll’s story was a didactic tale (for women), it was also presented as erotica (for men).

Pretty much everyone in the 19th century was familiar with this story. Hogarth’s images were printed onto decorative items such as fan-mounts (the part of a fan that’s not the stick and handle) and onto household items such as cups and saucers.

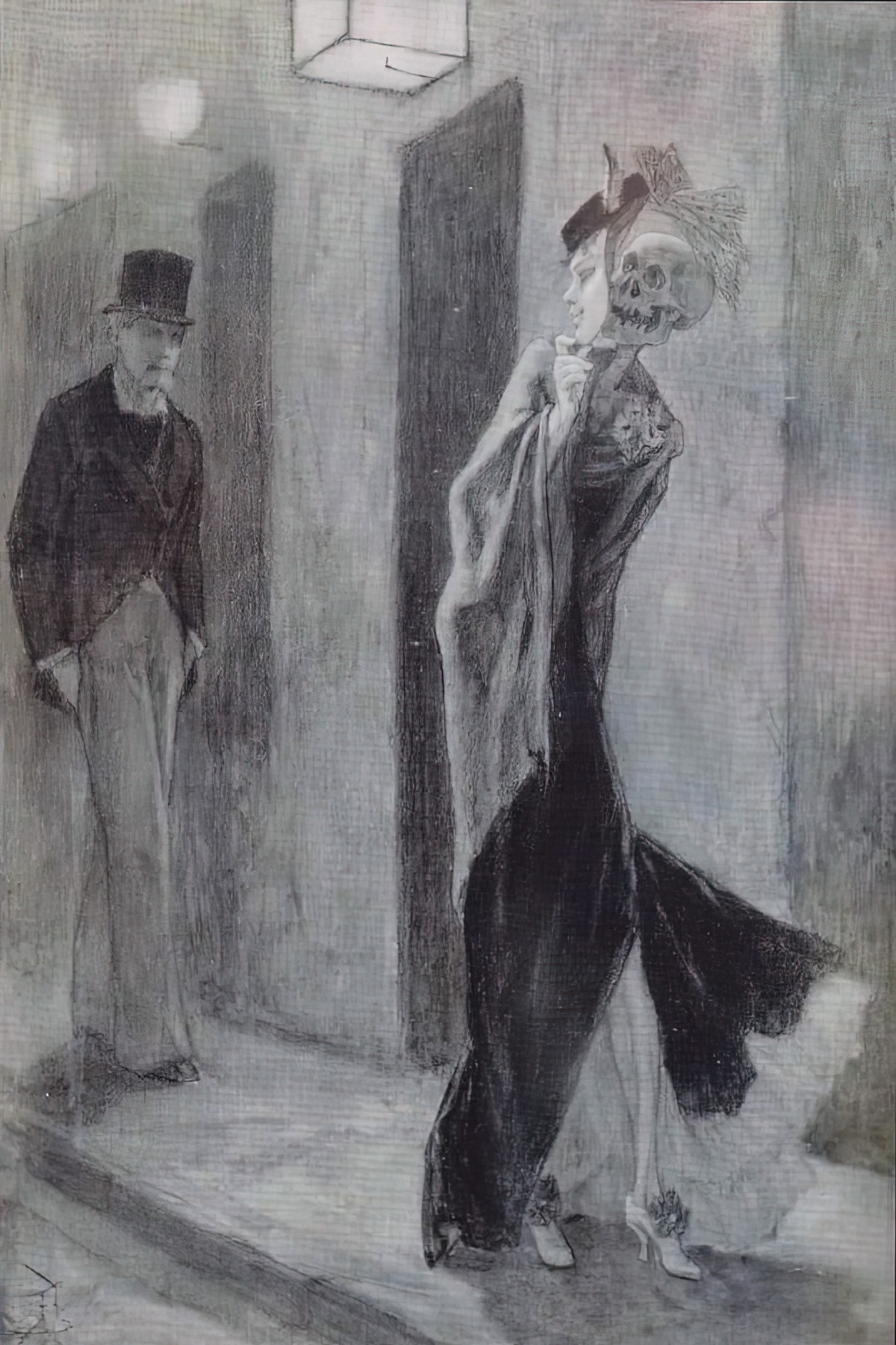

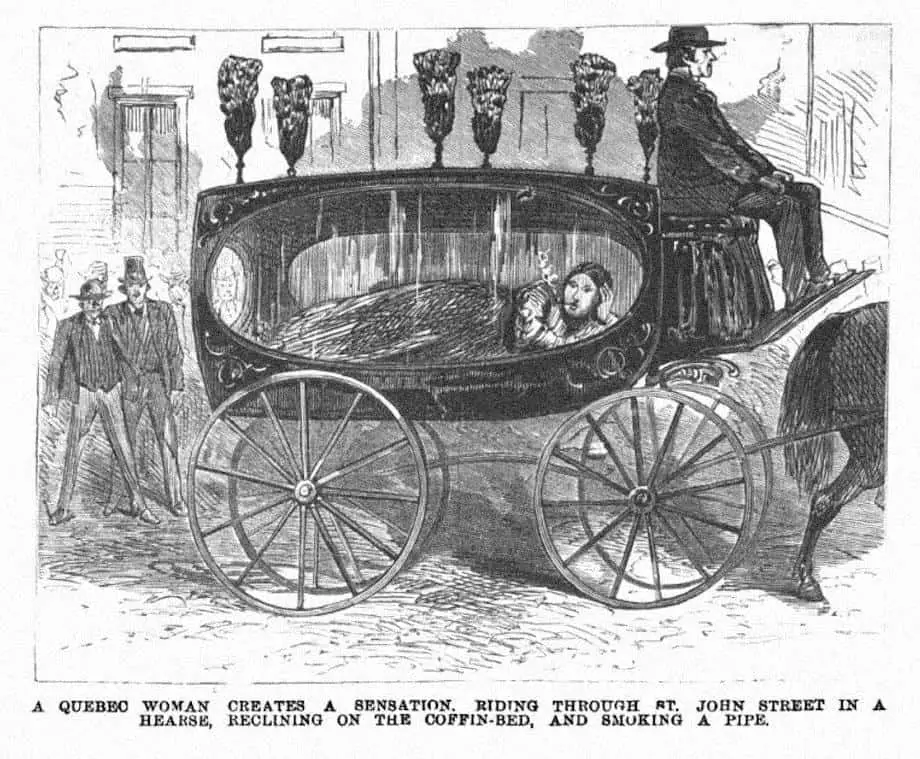

Newspaper articles about real women were influenced by this dominant narrative. “Fallen women”, “harlots” and “prostitutes” were presented to the hegemonic public as immoral and dangerous to society.

FEATURES OF A HARLOT’S PROGRESS STORY

Harlot’s Progress stories are linear — typically a form which serves masculine desire, in both the rhetorical and sexual sense of the word. (Feminine stories — those for and about women — more often tend to be circular in shape.)

- Heroines in Harlot’s Progress stories are presented as Good characters who deserve the best possible fate. However, until she is claimed by a man, all of her virtues remain suspect. (The man who claims her recognises her intrinsic goodness.)

- This ideal heroine follows a set path towards marriage and domesticity. Her quest is always the same: for the protective security of a publicly established virtuous reputation. [DESIRE]

- The Harlot’s Progress narrative starts with either seduction or sexual violence. This will show the audience how vulnerable she is.

- If she doesn’t have a father, she will need to find a father figure before she can secure a husband. [MENTOR]

- Before achieving marriage, the heroine navigates her way through hoards of scary men in landscapes fraught with sexual transgression. [SETTING]

- In these spaces, female modesty is presented as fragile. [WEAKNESS]

- If she succumbs to sexual impulses she will sabotage her chance at marriage and instead become a “fallen woman”. [MORAL DILEMMA]

- But the reader is constantly encouraged to worry that she will be a victim of male violence.

- The BIG STRUGGLE scene will include a situation in which the heroine has to evade predatory men and not be turned on by the threat of their violence.

- She must avoid venturing off the path (seen also in the Grimm versions of Little Red Riding Hood, heavily influenced by the Harlot’s Progress narrative in the versions they collected). If she ventures off the path, she will run the risk of falling into a much more dangerous story.

- The story usually ends with death. [NEW SITUATION]

Evelina by Frances Burney (1778) is considered the perfect example of The Harlot’s Progress narrative.

COULD THE HARLOT’S PROGRESS NARRATIVE BE FEMINIST?

Some critics (e.g. Margaret Homans) have argued that linear narratives tend to correlate with static narratives. By static, we mean narratives which deliberately invoke stasis. However, critics such as Roxanne Eberle have argued that (proto-) feminists made use of familiar linear narratives in order to do feminist things with them. Linear stories are perfectly adequate in allowing for much experimentation. (E.g. A story can still be linear and not kill the heroine off at the end.)

The heroines of these books were rewarded with good husbands, financial resources and a domestic form of power. (Nancy Armstrong calls this specific form of power ‘the power of domestic surveillance’ in her book Desire and Domestic Fiction.)

Ultimately, these scripts serve the middle-class by presenting us with an ideal of the public male entrepreneur and his private angel in the house.

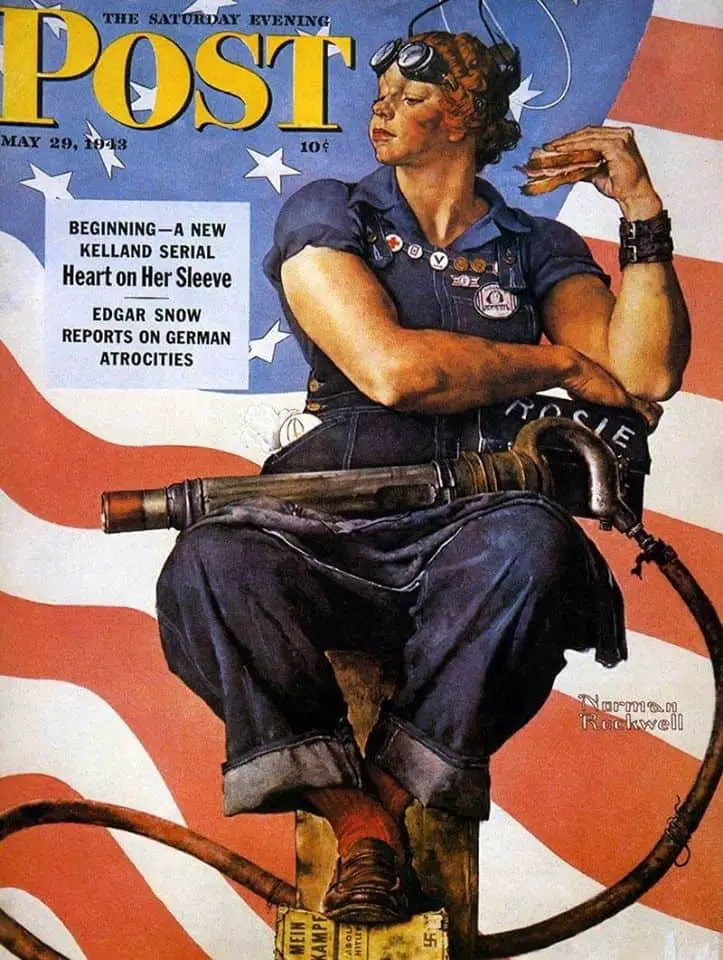

Importantly, these weren’t the only books being written in this era. At the turn of the 19th century the very construct of the British woman was much debated. The world was at war and Britain was grappling with social upheaval — there were massive changes going on in their rural, agrarian and feudal class system. How important were women in all this? Many people were talking about it.

‘Conservatives’ wanted to keep women virtuous and in the domestic/private sphere. ‘Radicals’ wanted to educate women well and enter the public sphere.

So alongside these archetypal Harlot’s Progress narratives we now saw the rise of the sexually transgressive but articulate heroine in fiction. Proto-feminist works (e.g. by Mary Wollstonecraft) starred heroines who had been ‘robbed’ of their chastity by men uninterested in marriage. Some heroines robbed of chastity critiqued the social system rather than succumbed to self-abasement. Proto-feminist writers found the Harlot’s Progress useful because it contained a paradox: It was very well-known by audiences, so provided a framework for variation. (Much as the mythic structure functions in popular storytelling today.) These porto-feminist variations on The Harlot’s Progress was also linear in shape, but also discursive (jumping from subject to subject, probably back and forth through time).

Progressive women were interested in Harlot’s Progress stories because they offer an extreme example of the duality of ‘body’ and ‘mind’ (morality) that enlightened women were dealing with in their own lives. Conservatives believed that unchaste women were dangerous and therefore dangerous members of society. Radical women writers challenged this belief by asking people to locate morality in the mind, separate from what a woman did with her body, or what others did to her body. (Occasionally these writers even dealt with matters of the heart.)

THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN REAL SEX WORK AND FICTIONAL SEX WORK

Importantly, novels were not written for the labouring-poor classes. Books were expensive and largely read by richer people who had no idea what real sex work looked like.

Real world sex work of this era looked very little like the archetypal fictional version. Most English sex workers were poor urban women who moved in and out of sex work as a way to supplement their families’ incomes. These women were not necessarily stigmatised within their own communities. This depended on their class. Norms within the sex work/labouring-poor culture of England at the time were distinct from the norms of the dominant culture. Any type of sex outside marriage was frowned upon. Let’s just say sex work didn’t receive especial scorn.

Sex work wasn’t pathologised and regulated until the 1880s. It was at this point that English sex workers started to become stigmatised even within their own communities.

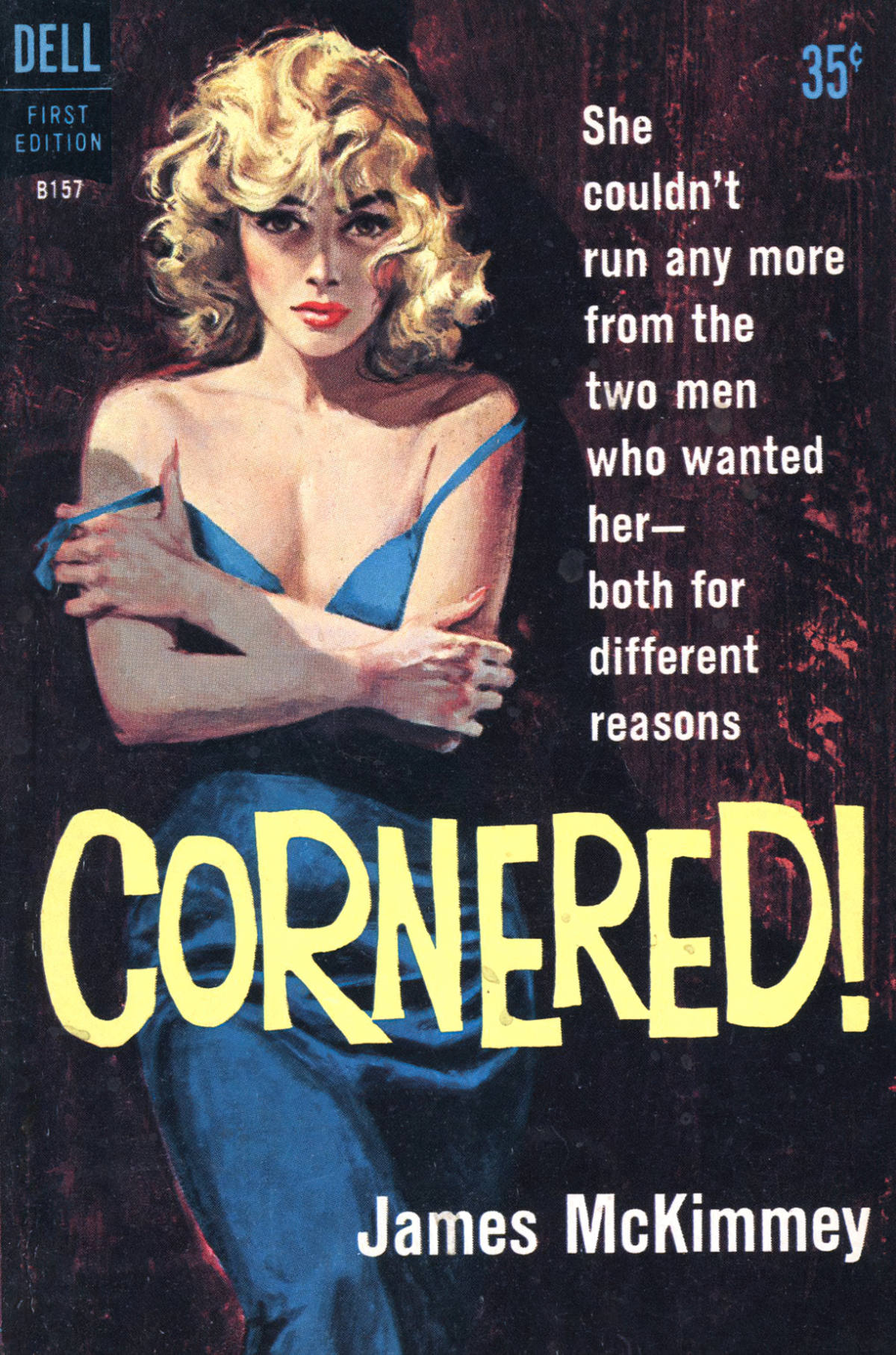

THE HARLOT’S PROGRESS AND CONTEMPORARY STORYTELLING

WOMEN ARE STILL HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR (AVOIDING) SEXUAL ASSAULTS

I have just described 18th and 19th novels which starred heroines whose virtue alone could overcome sexual aggression, transforming male desire into middle-class love. But is this idea really dead?

When a police officer speaks to the public about a violent rape that took place in a public park, he’ll all-too-often tell women to stay away from parks. He’ll tell women not to get drunk if women don’t want to get raped. The problem with these broad service public announcements is this: Individual women may indeed avoid rapes in parks by restricting their own movements. But women are still far more likely to endure abuse in their own homes. And if individual women were able to avoid parks, predators would move on to another victim. Perpetrators are still not held to full account.

SEX WORKERS ARE STILL SEEN AS FALLEN, OSTRACISED WOMEN

Sex trafficking (and other kinds of human trafficking) remain a significant international problem. However, many sex workers today have chosen their profession and resent the enduring idea that they must be stuck in that job because of desperation, substance abuse or morally bad choices.

QUESTIONS TO ASK WHEN EVALUATING NARRATIVES

- When a story contains the rape/abuse of a woman or marginalised identity, is this presented as punishment for sexual transgression?

- Outside specific realms of erotica, is this punishment meted out in such a way that a voyeuristic audience would enjoy it? Would a misogynistic audience enjoy it?

- When reading/watching stories about LGBTQ characters, do these characters die? If so, what is the narrative purpose?

- Are woman characters given their own shortcomings and moral flaws? If not, the story may be leaning on the trope of The Strong Female Character. The problem with Strong Female Characters is that they don’t get their own arcs. Characters with no arc can never be the true stars of any story.

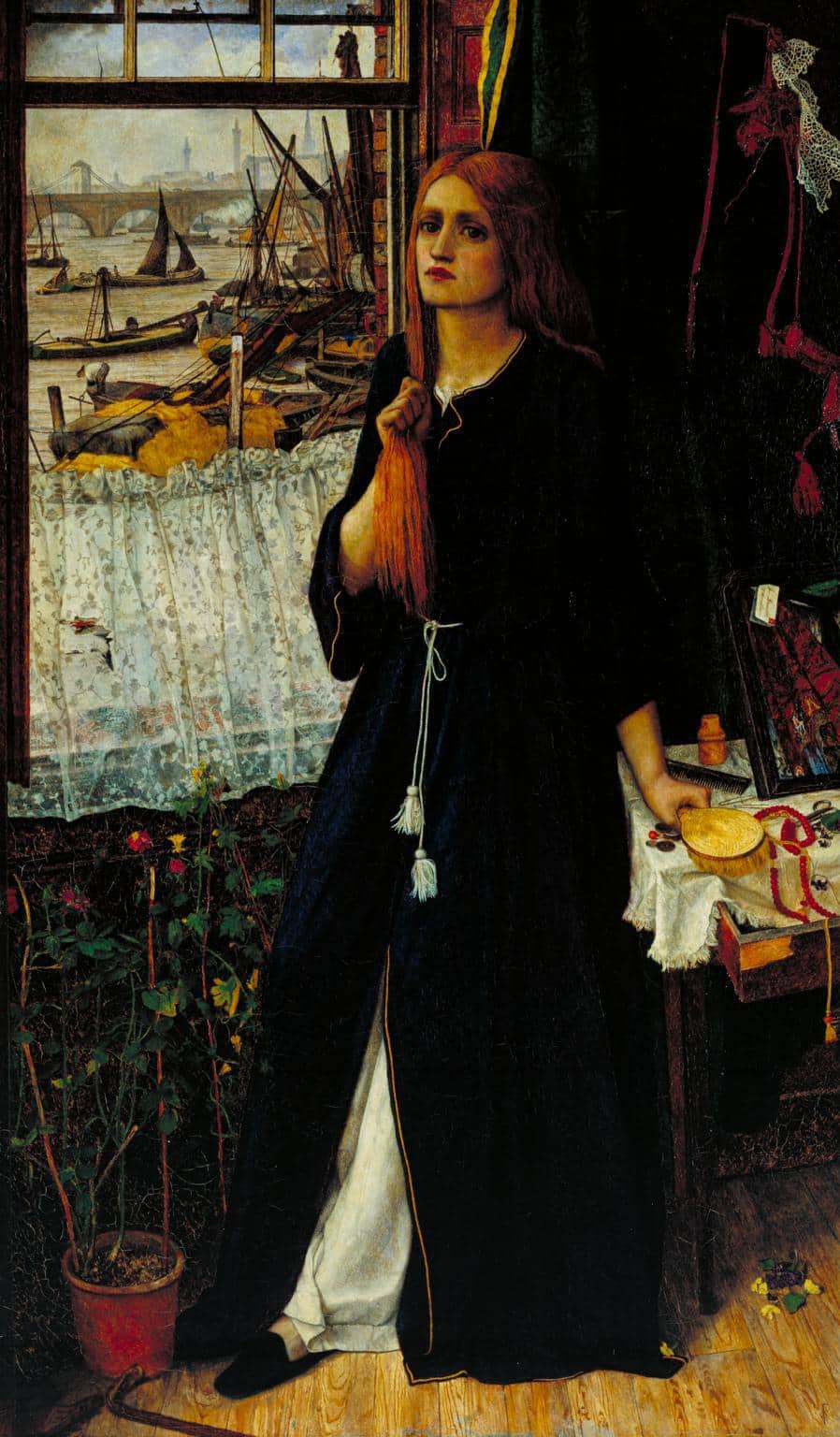

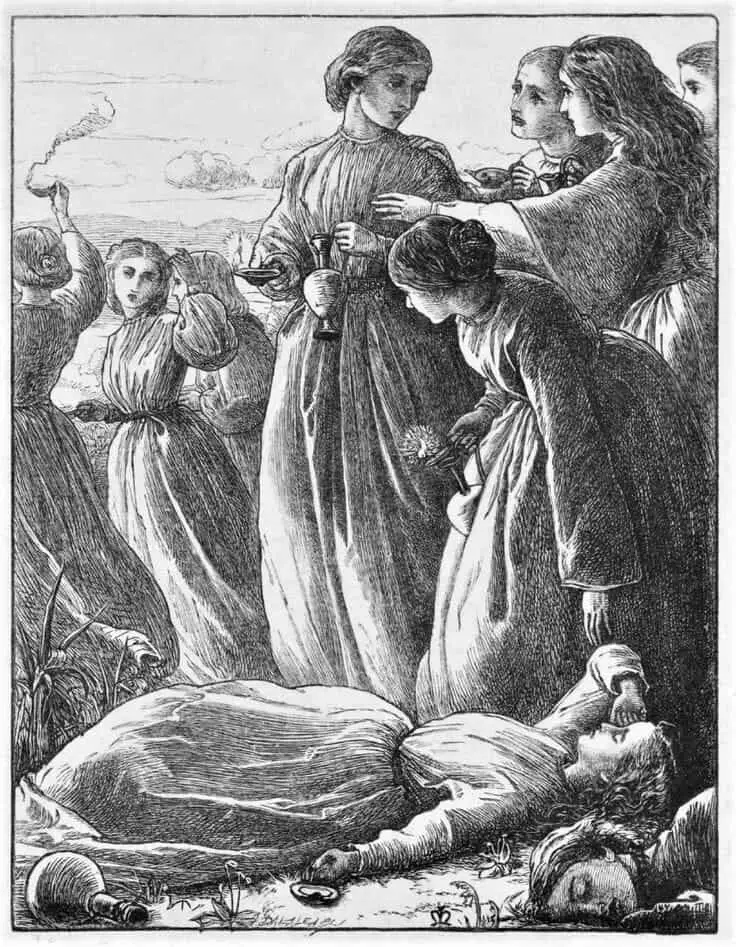

Header painting: Thoughts of the Past exhibited 1859 John Roddam Spencer Stanhope 1829-1908. Stanhope’s portrayal of a prostitute in her lodging, who is suddenly overcome with remorse for her situation, reproduces the theme of the guilt-ridden prostitute that was prevalent in literature and paintings of the 1850s and 1860s, especially among the Pre-Raphaelites and their followers.