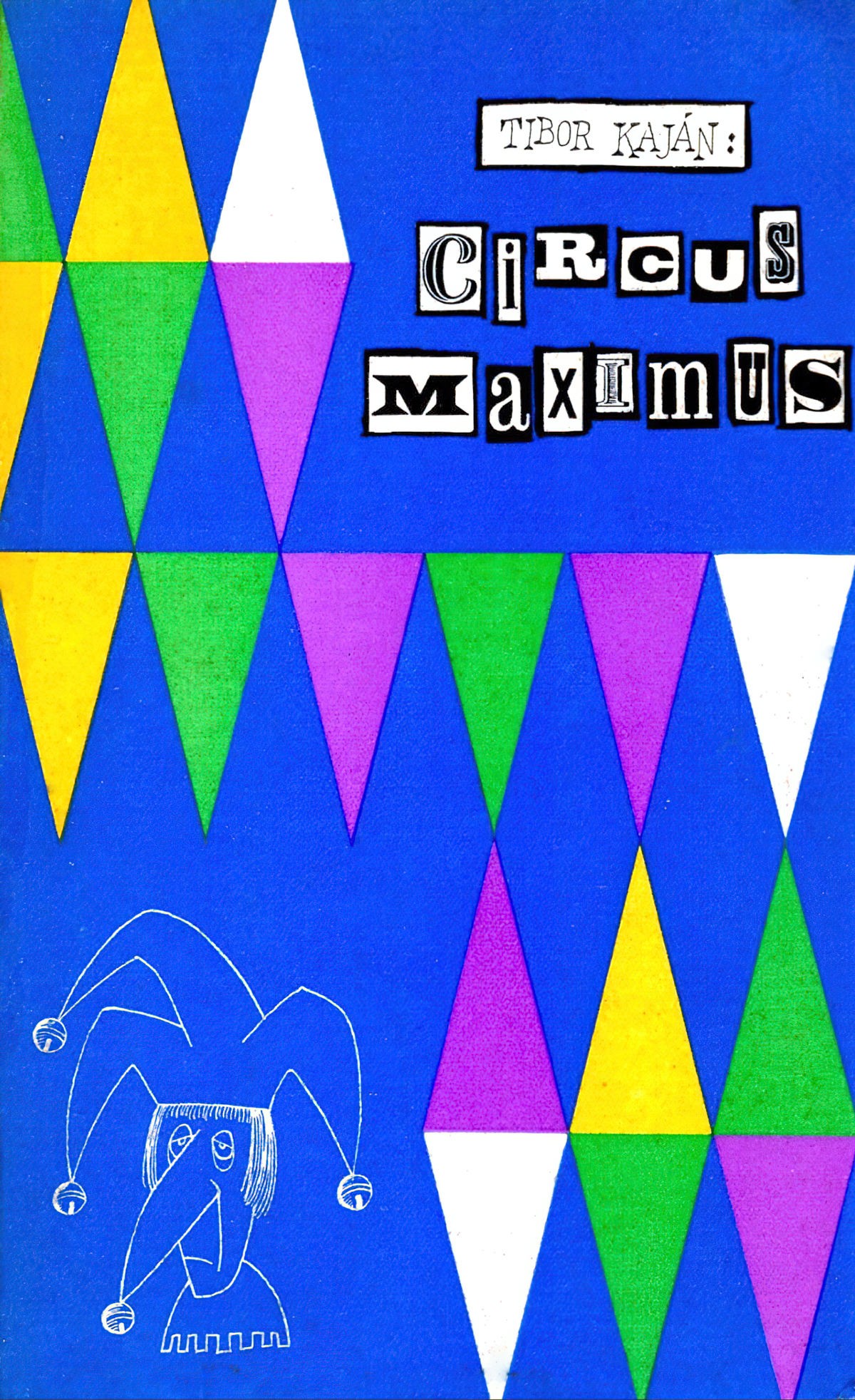

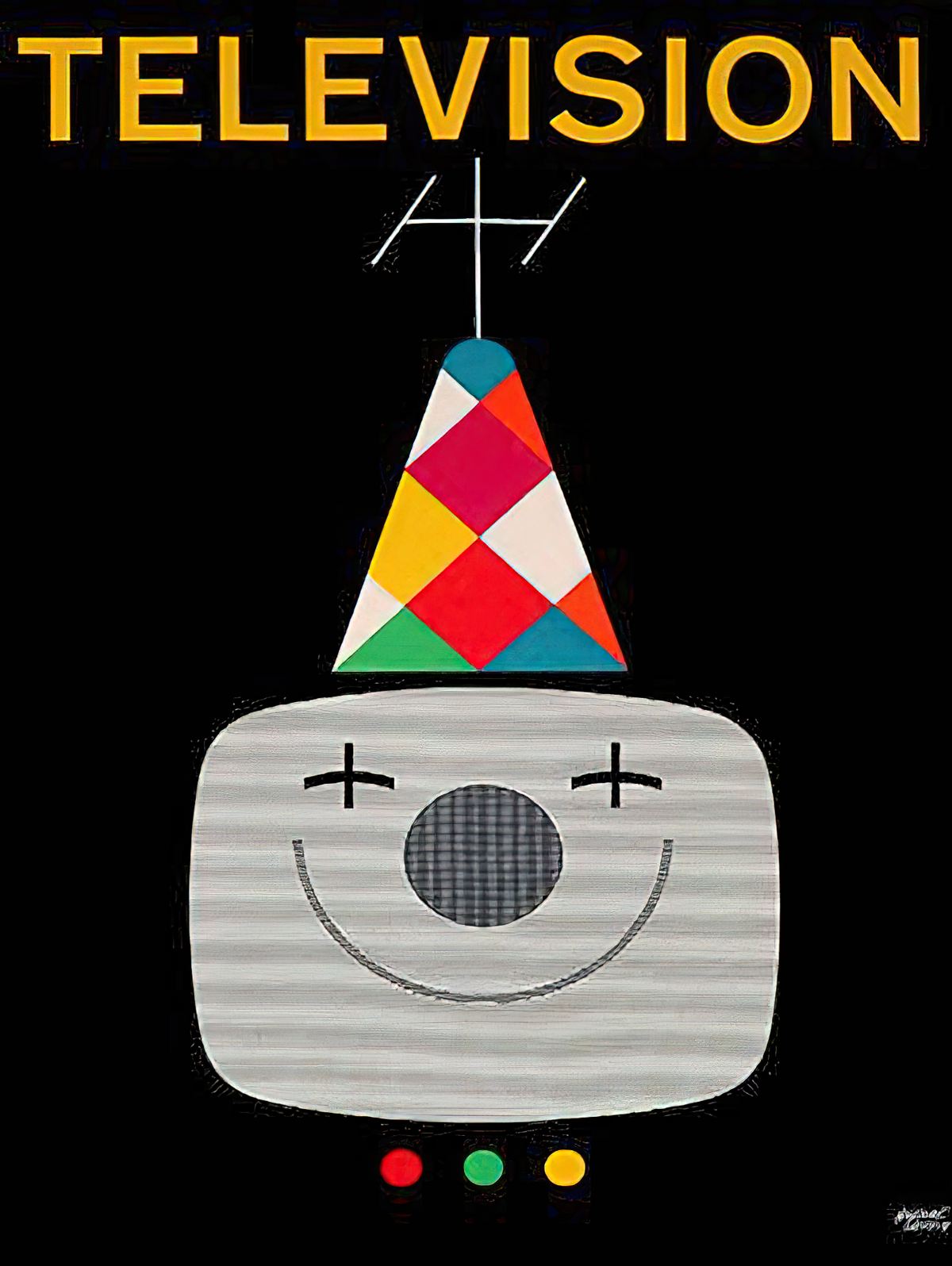

Why is the triangle/diamond/lozenge shape associated with the circus? I started to wonder this after collecting a bunch of circus related art. The book cover below is a great example: Even without the line drawing of the jester, those shapes themselves suggest a circus.

I came across the following paper: Undressing and Redressing The Harlequin: An Australian designer’s perspective, written by Julie Parsons. All became clear. The following notes draw from the thesis.

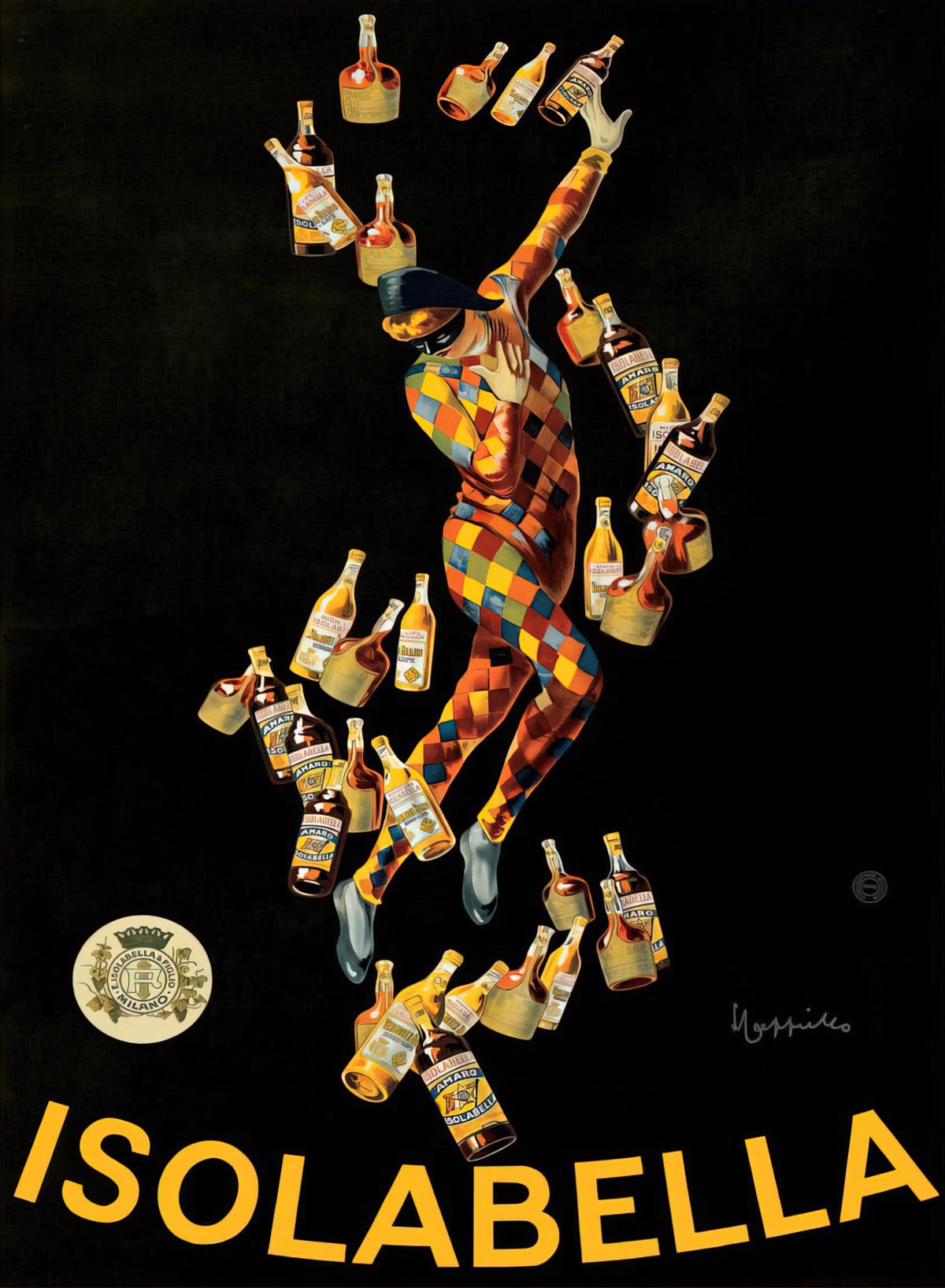

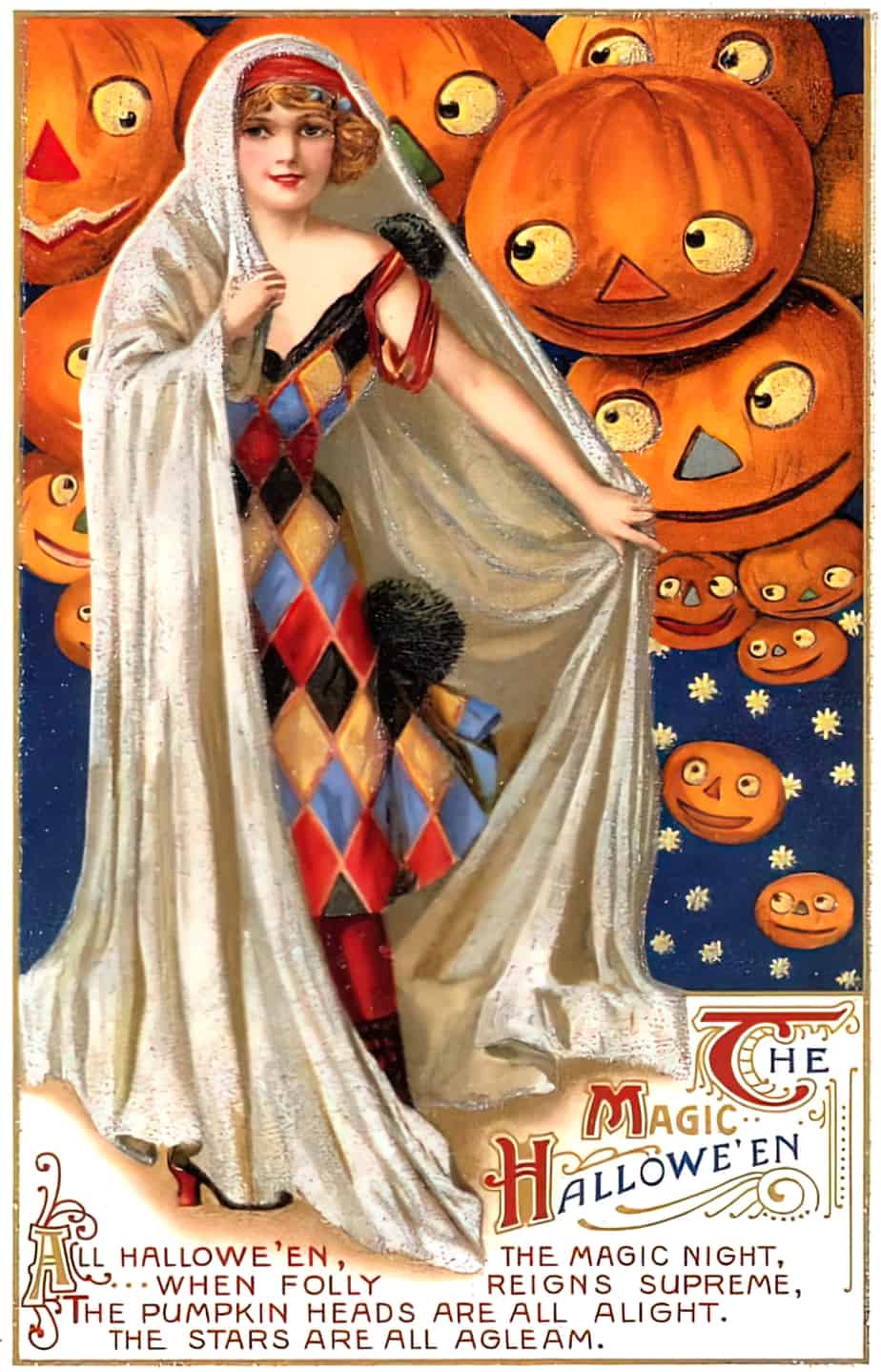

That lozenge pattern is inspired by the pattern of the Harlequin costume, which I didn’t realise was in fashion for 500 years. (What other costume has been around that long?)

WHAT IS A HARLEQUIN?

The Harlequin is a stock character from commedia dell’arte. There is a clear ancestor of the harlequin that came before, however: the lenones (flat feet) and phallophores (black face foreign slaves) of Roman theatre. There is also a theory that the harlequin comes from a medieval French demon called the Herlequin. I can see how that theory fits…

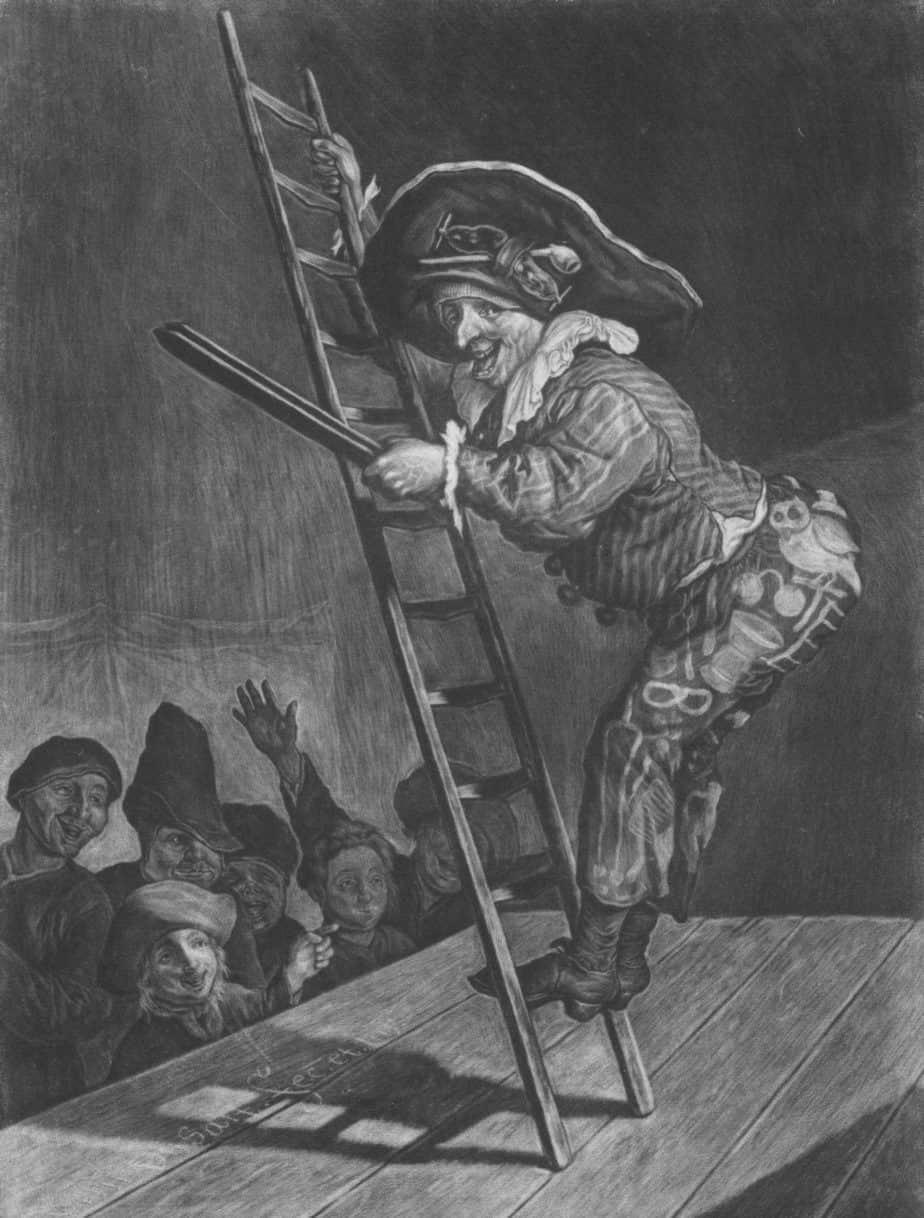

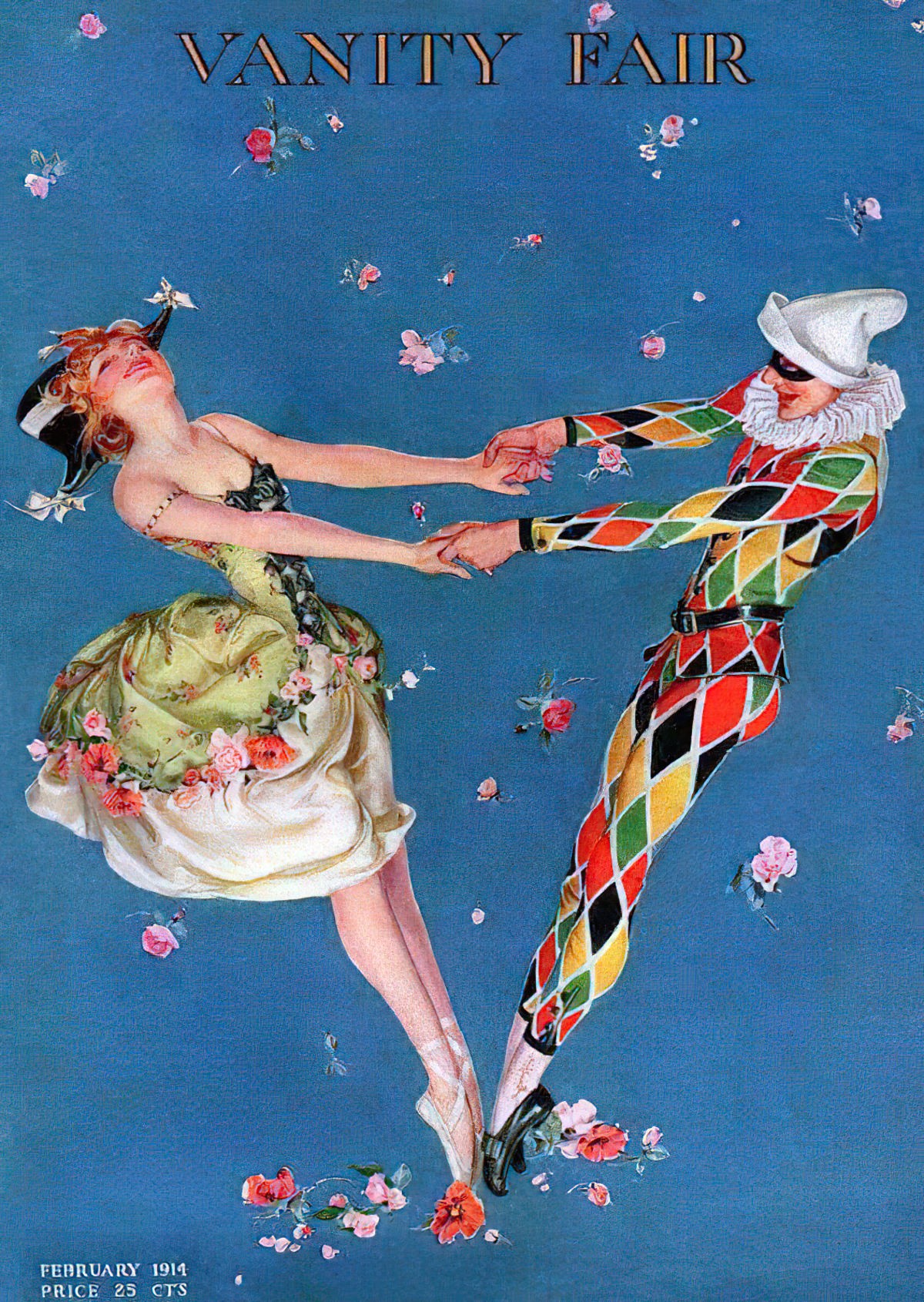

Commedia dell’arte emerged in Italy and France during the 1500s. There are four main categories of stock characters from commedia dell’arte: (masked) servants, old men, (also masked), captains and lovers. (You can tell a lover because their name goes something like Flavio or Isabella.) Masks are important across all types of storytelling, but are vital in commedia dell’arte, inseparable from the character who wears one.

The stock character of ‘clown’ was part of the servant class, or zanni.

Because these stock characters are designed to be readily identifiable, they each wear a certain ‘uniform’. Melodrama relies on stock characters, and commedia dell’arte is peak melodrama, with themes you’d recognise as midday-soapy today.

The categories of stock characters have special significance to Italian audiences, because each of them is supposed to have come from a specific region of Italy. Harlequin is thought to come from Bergamo, in Northern Italy. The Bertano valley forms a natural amphitheatre. The regional stereotype suggests fools come from the lower end of the town, and smart people come from the upper end.

Fools and Other Unwise Persons, a categorisation from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966

PSYCHOLOGICAL SHORTCOMING OF THE HARLEQUIN

The Harlequin comes from both upper and lower strata of society. He is ambiguous in many ways and transgresses boundaries, which makes him camp.

Before the sixteenth century, he didn’t have a physical form in the popular imagination, and he has been compared to a slippery, volatile, elusive dolphin, loach or sylph, or a droll and whimsical god. This ancient version of the harlequin reminds me a bit of The Pied Piper of Hamelin, who is not normally depicted wearing diamond shapes or black masks or phalluses, but who is likewise volatile, whimsical and basically the devil. He does wear the exotic patched suit.

The contemporary (500 year old) harlequin is remarkably individuated as a character. According to Jean-Francois Marmontel (1996), he is:

- a rake

- an overgrown boy

- has occasional gleams of intelligence

- his mistakes and clumsiness have a wayward clarm (like Bella Swan, then?)

- He moves with the agile grace of a young cat

- is superficially coarse

- and therefore funny.

- His role is that of a faithful valet

- He is patient (again, like a cat?)

- credulous

- greedy

- eternally amorous

- constantly in difficulty

- You can hurt and comfort him as easily as you can a child.

- When he is grieving, the audience enjoys this as much as we enjoy him in a joyful state.

The Harlequin, especially when conflated with Mestopheles, is an arrogant figure. Believe it or not, the Harlequin is actually the ‘straight guy’ to the antics of other comedic figures. Stage and circus mingled during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, which is how all these characters ended up with the same white face. The modern-day white faced clown may be a descendent of the Harlequin’s mask, though clown scholars disagree about that one.

“In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries when stage and circus mingled”

(Hartnoll, 1967. p.178), Pantaloon, Clown and Harlequin found their way to the circus

ring. Harlequin played the arrogant straight-faced clown to the others’ antics. Clown

makeup was an important element in this transition of the Harlequin figure.

DESIRE OF THE HARLEQUIN

The harlequin is driven by fear and/or love. He’s an adrenaline junkie and once he gets riled up, he is raring to go. Carnivalesque mischief ensues.

THE HARLEQUIN’S CHARACTER ARC

Stock characters don’t typically undergo a character arc, but the harlequin is a chameleon who changes to suit the environment.

The difference between clown make up and Harlequin make up: The Harlequin make up emphasises false supriority. This preempts his fall from grace. He is sometimes a victim who becomes the perpetrator in a cycle of abuse.

WORDS ASSOCIATED WITH THE HARLEQUIN

Arlecchino

Italian for Harlequin

Arlequino

French for Harlequin

Guillaire

The Italian word for a jester with shamanistic characteristics. They dress in brightly coloured costumes. (Was The Pied Piper part of this tradition? Possibly. But some illustrators take ‘pied’ to mean he was poor. He wasn’t rich enough to buy clothes, so cobbled his garments together out of off-cuts.)

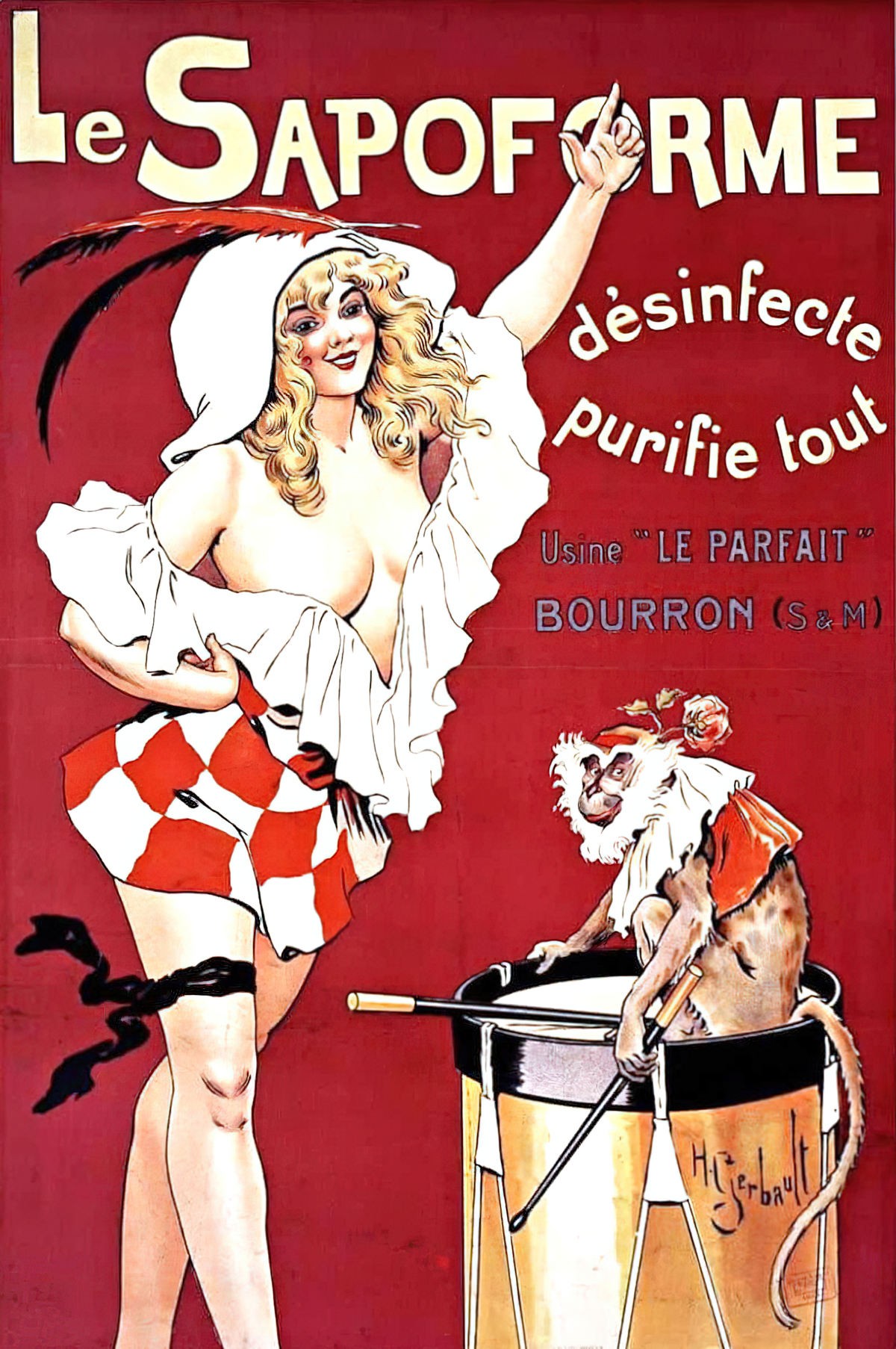

Columbine or Columbina

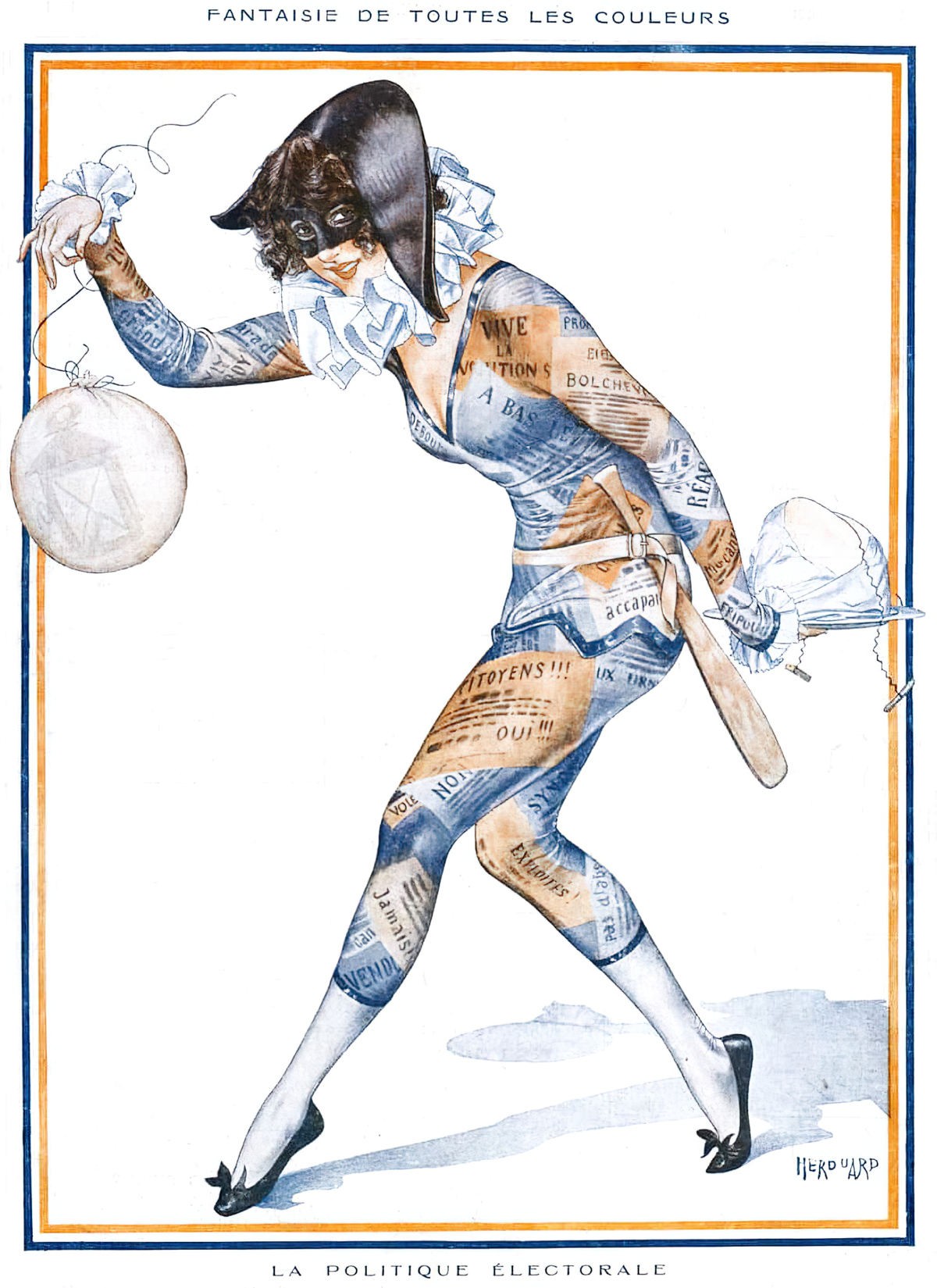

The Harlequin’s female counterpart. She is sometimes called Harlequina. She’s not fully distinct from the Harlequin because at some points she merges with Harlequin during antics that require the interchanging of costumes. Sometimes she appears in his suit, at other times he appears in her dress. This is all part of the ancient tradition of crossdressing for laughs. We have collectively dispensed with the blackface of antiquity, but crossdressing for gags remains strong, despite reinforcing an outdated notion of the gender binary.

Descendents of the female Harlequin can be seen in many comic book characters. You’ll recognise her because of her cat-eye mask e.g. Molly Mayne. Partly because of her female status in the gender hierarchy she is an underdog character but she fits all along the moral spectrum, between good and evil, as the storyteller sees fit. The glasses worn by Dame Edna Everage (among other things) suggest that Dame Edna is an Australian descendent of the Harlequin. The cartoon character Cecily, created by New Zealand cartoonist Celia Allison, also wears Harlequin glasses and is similarly subversive.

Harlequinesque

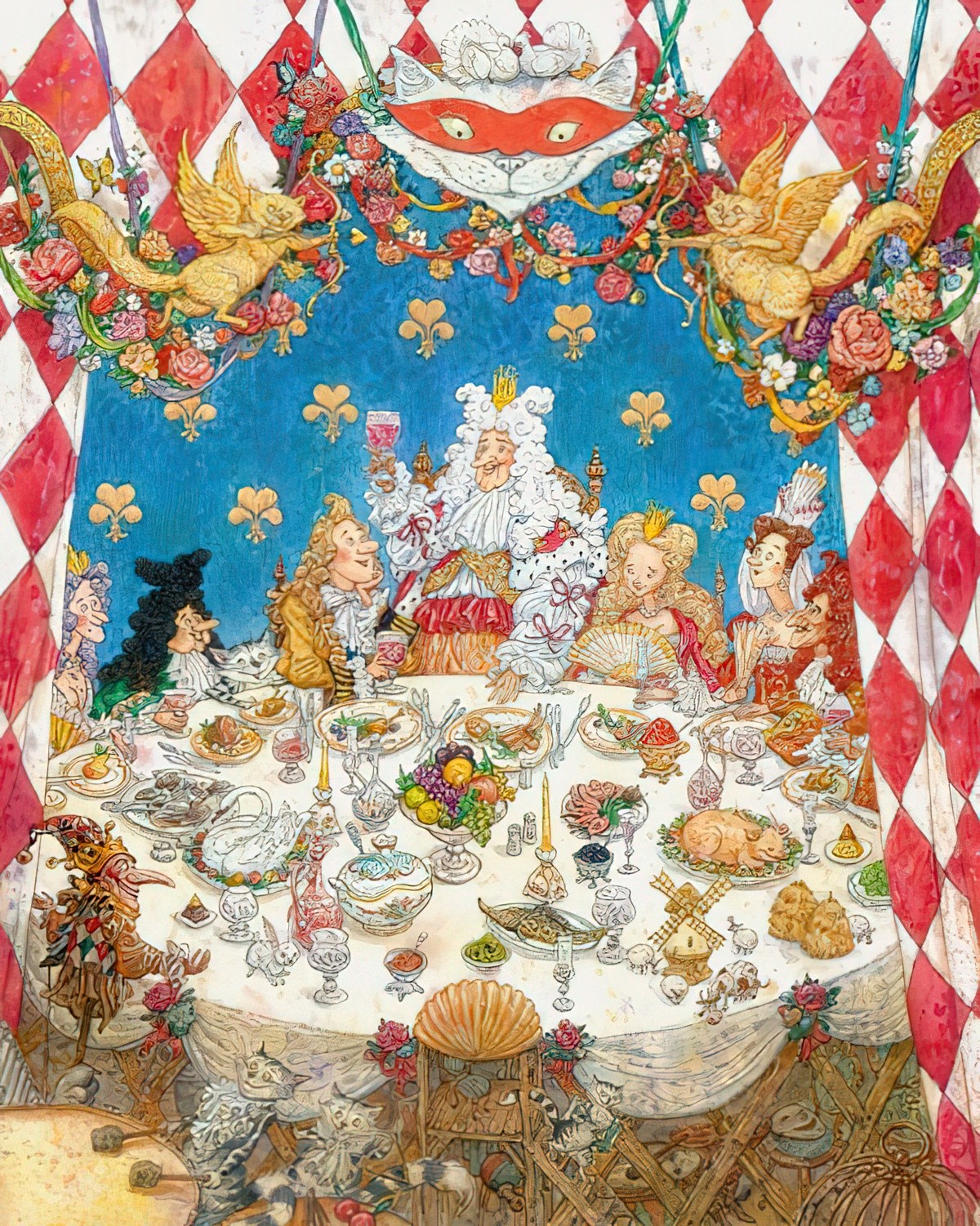

The phenomenon of the harlequin. In the manner of Harlequin. Cf. carnivalesque. In ancient carnival, hierarchy is temporarily overthrown as people spend designated days per year having fun. What distinguishes the ‘harlequin’ from the ‘carnival’ is the involvement of masks, or mask-like costumes, in which the wearer more fully embodies a carnivalesque character. Jesters , minstrels and fools started wearing costumes in the middle ages. They might play the diabolical king of dead souls in carnivals, or the buffoon in the wealthy courts. Whitehall said in 1950 that harlequinesque costumes are ‘characterised by variety in colour’.

Harlequinade

the part of a traditional pantomime in which Harlequin/clowns/jesters play a leading role. In earlier usage, people used ‘harlequinade’ to mean foolish or ridiculous behaviour. The harlequinade had no real plot and little if any dialogue. It was fast and called into play full acrobatic antics, and is basically a satire of popular comedy itself. Harlequinades were initially performed around the Christmas and New Year holiday season and sometimes over Easter. Sometimes audience participation was encouraged, with catch phrases that became popular.

Mestipheles

This is the ‘fallen angel’ Faust sold his soul to. He is sometimes conflated with the Harlequin, and we see him in the same lozenge-patterned suit. He tends to have a white face with the quirked eyebrow, suggesting intellectual superiority.

Multinationalism

Some philosophers have come to accept Harlequin as a visual code for the union of multi-nationalities.

Slapstick

The Harlequin carried a stick known as an actual slapstick (though these days it most often refers to a type of physical comedy). The slapstick is a stick split into two but formed as one at the handle end. The slapstick makes a loud, surprising sound when the holder makes a sudden move. There’s a bit of an art to it. The art of using a slapstick may have contributed to Harlequin’s unique sudden actions. Sticks have various uses in this kind of pantomime, including doubling as phallus. You can also stick a (doll) head on it and now it’s a puppet. It can also be used as a weapon, usually against Pantalone. Slapsticks evolved into magic wands and wooden swords.

Header: Harlequin designs were by David Hockney