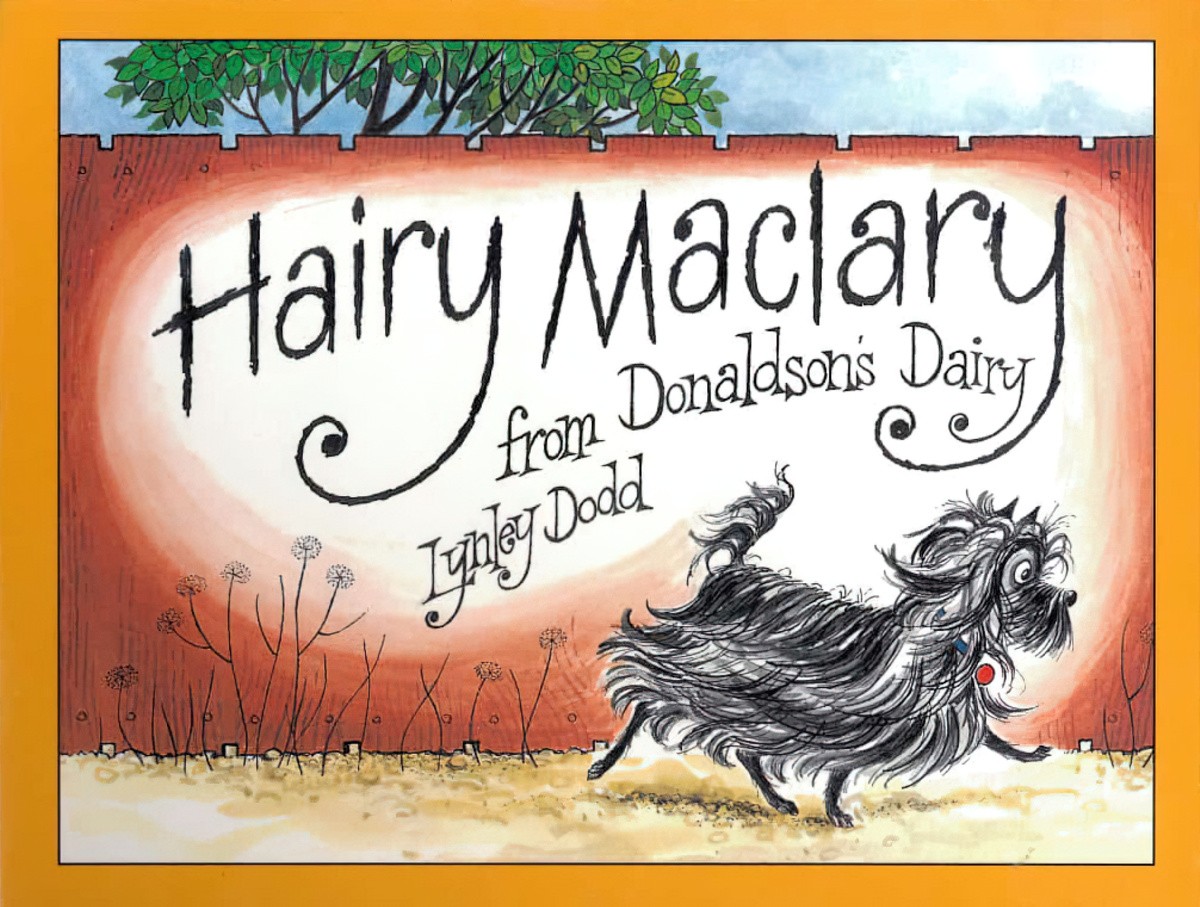

Hairy Maclary From Donaldson’s Dairy (1983) is a cumulative rhyming picture book written and illustrated by New Zealand storyteller Lynley Dodd. This is the book which began the Hairy Maclary series.

There’s a long history of cumulative stories in folk tale. See the CUMULATIVE TALES entry from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966.

WHAT KIND OF DOG IS HAIRY MACLARY?

Honestly, he could be almost anything! I have a dog who looks very much like Hairy Maclary, but he’s a Border Collie, miniature poodle cross. Passersby ask me if he’s a bearded Collie. I frequently call my dog Hairy Maclary, and if I knew he was going to grow this hairy, I’d have called him Hairy, for sure.

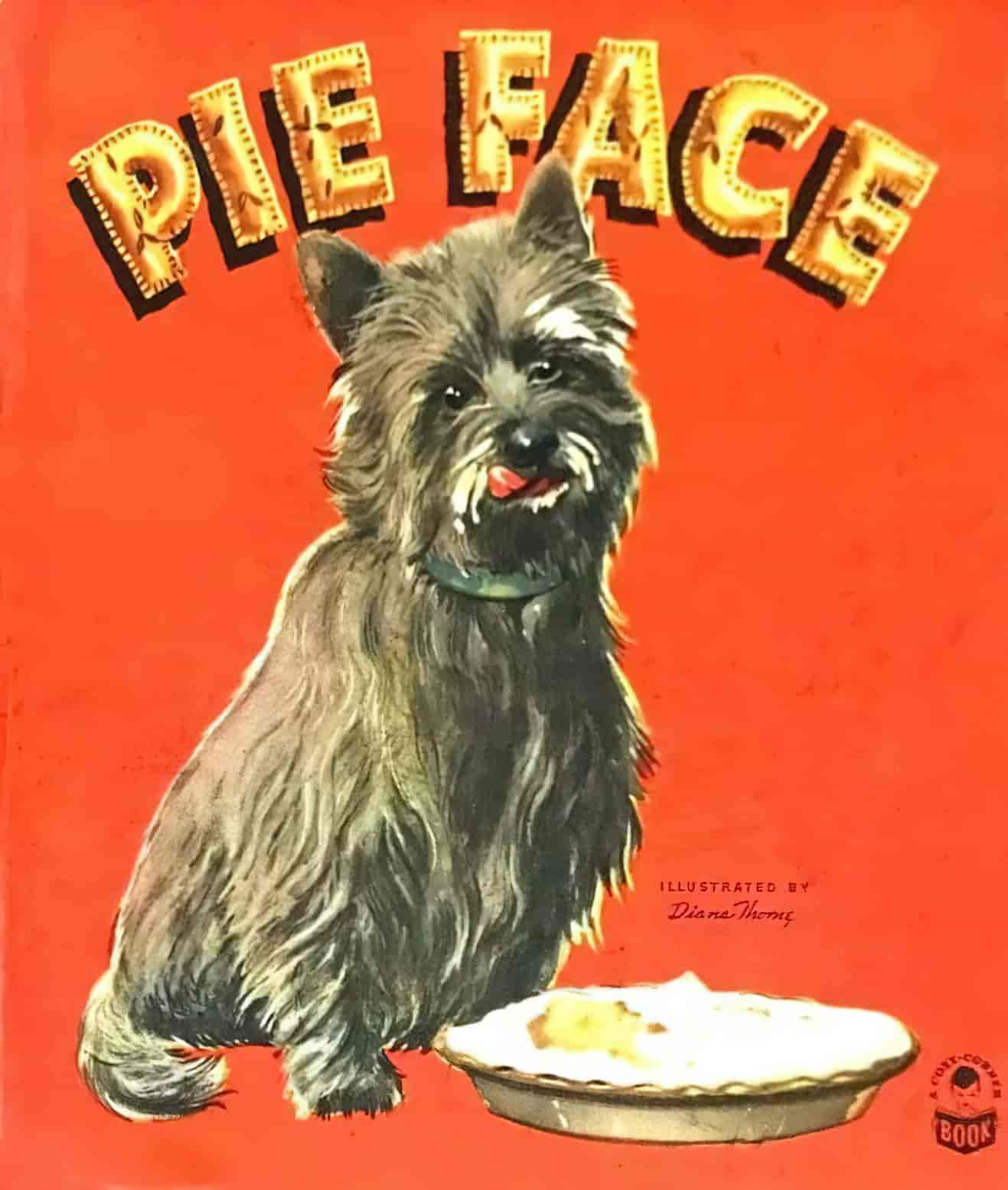

Apparently Hairy Maclary, the real one, is a Skye Terrier, a breed developed on the Isle of Skye, Scotland.

The Skye Terrier is a breed of dog that is a long, low, hardy terrier and “one of the most endangered native dog breeds in the United Kingdom” according to The Kennel Club.

Wikipedia

Even if you’ve never met a Skye Terrier, you may have met a Scottish Terrier. What’s the difference? Skye Terriers are heavier (but not taller) and have a soft coat rather than wiry. Skye Terriers are better watchdogs, apparently. Importantly for this series, Skye Terriers are prone to wanderlust and love to roam. Their chunky bodies mean they are often strong enough to escape through gates and whatnot.

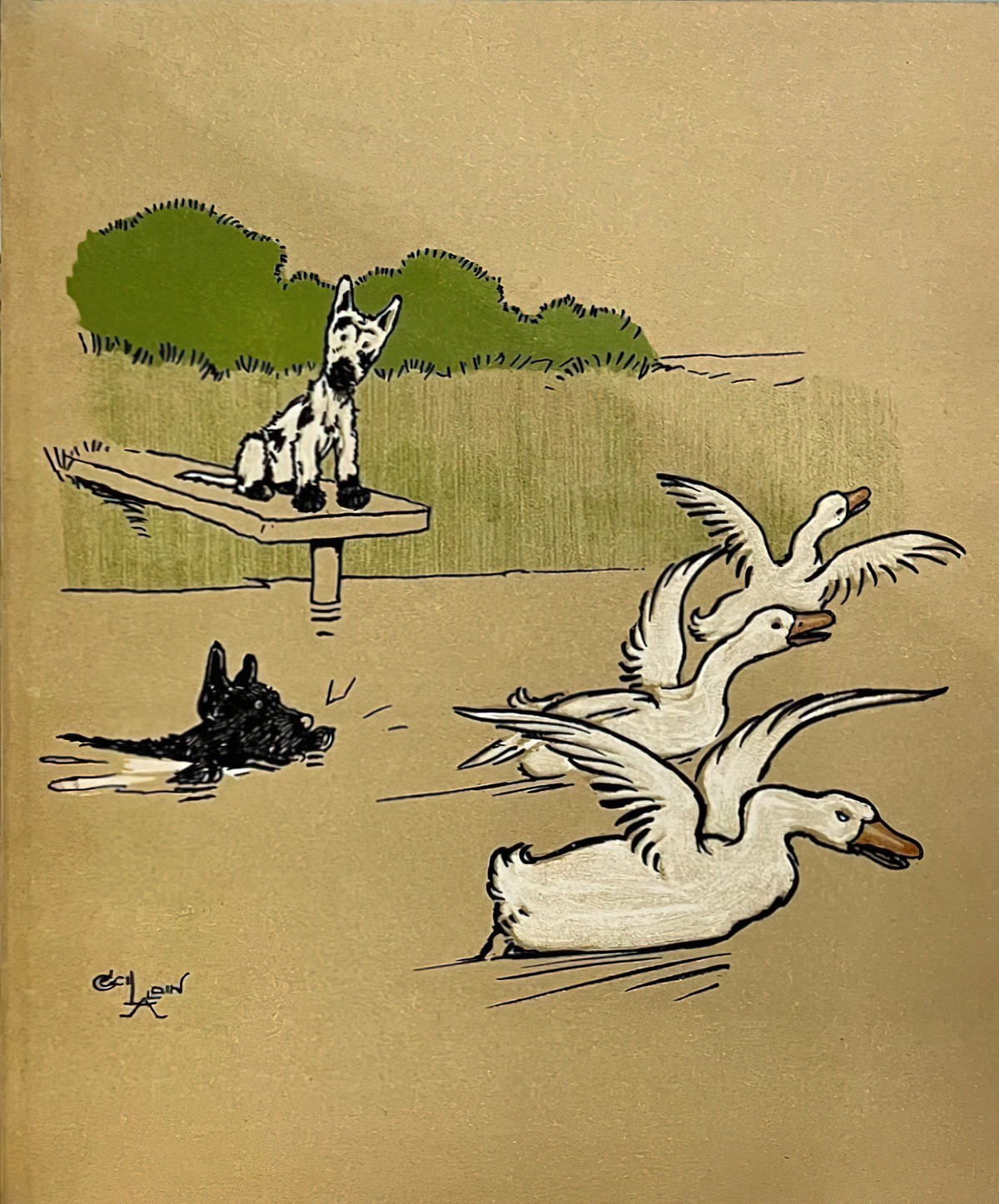

Both of these kinds of terriers are said to have ‘low to average’ intelligence compared to other dogs which, for storytelling purposes, makes them excellent low mimetic heroes (to use the terminology of Northrop Frye). Low mimetic heroes are just like us only, if anything, a little less competent. They get themselves into hilarious scrapes. We can enjoy reading about someone even less competent than ourselves. It’s important that storytellers look after these characters and send them home at the end of the story safe and sound. Whatever befalls them can’t be too bad.

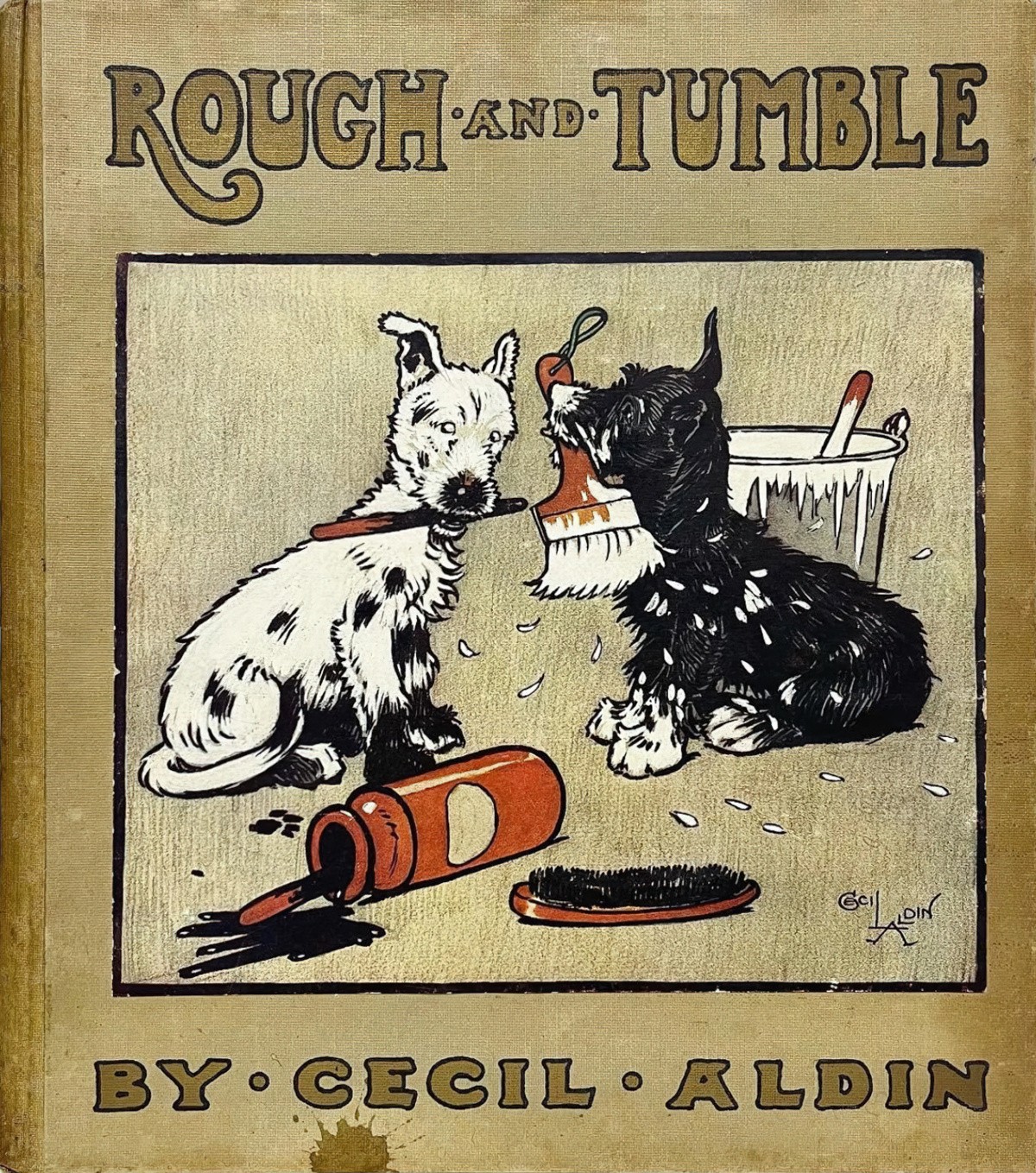

PREDECESSORS TO HAIRY MACLARY

Lynley Dodd was influenced by pets she knew in real life. What about children’s literature influences? Let’s talk about a tentpole dog picture book series which came before Hairy Maclary, albeit from another English speaking country.

HARRY THE DIRTY DOG

Zion and Bloy Graham’s Harry series about Harry The Dirty Dog is an ancestor of Hairy Maclary (though American books weren’t all that popular in New Zealand when Lynley Dodd’s generation were growing up). The Harry series is a set of carnivalesque picture books in which a dog sets off on a mischievous adventure independent of his family.

In picture books about pets, the pet is clearly a stand-in for the child. No children are mentioned in the Hairy Maclary household, but Harry The Dirty Dog has a boy and a girl at home. This boy and girl are cast in parental role. In order to have carnivalesque fun, the dog must escape the watchful eye of his family, and this includes the children. Some picture books cast the pet as a playmate. Other picture books about animals cast children into responsible caregiving roles.

This is fairly typical of pet books from earlier in the 20th century. Lynley Dodd’s series felt fresh partly because there’s no didacticism at all, really. No punishment. Just fun.

SIMILARITIES BETWEEN HARRY THE DIRTY DOG AND HAIRY MACLARY

Harry, like Hairy Maclary, is a beloved pet dog who lives with a family, trying his best to get along in a human world.

To what extent are these dogs anthropomorphised? Hairy Maclary and Harry both display identifiably human emotions (though dog-owners might argue that these are all emotions that are felt just as keenly by dogs). Specifically human: their self-consciousness. Harry looks into a mirror and recognises the reflection as his own. This is developmentally sophisticated. (Even human toddlers can’t do it.) Hairy Maclary also seems to feel some self-consciousness in a subsequent story when he wins the prize for ‘scruffiest cat’ after barging into the local cat show.

HAIRY MACLARY AND PRIDE AND… PREJUDICE?

Lynley Dodd herself names Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice as an inspiration for the cast of Hairy Maclary.

What Dodd – Dame Lynley Dodd to be correct – says impresses her about Austen is her language and the wonderful characters she created. “Who could do better than Mr Collins (the unctuous vicar in Pride and Prejudice)? It’s really just the fact that I love language and I want the language to sing for the children.”

Lynley Dodd reveals the secret of Hairy Maclary

It’s an immensely fun thought experiment to cast Lynley Dodd’s Hairy Maclary characters onto the cast of Pride and Prejudice. Who maps onto who, do you think? Schnitzel Von Krumm is clearly a member of the aristocracy, so he’d be Darcy, I guess?

SETTING OF HAIRY MACLARY FROM DONALDSON’S DAIRY

Australians naturally think that ‘dairy’ is a shortening ‘dairy farm’ but it in fact refers to the old style 1980s corner shop.

In 2012, this stupid video went viral and everyone in NZ started saying ‘nek minnit’. “I left my scooter outside the dairy. Nek minnit…” The guy left his scooter outside the corner shop, not outside a dairy farm. No one can say ‘next minute’ in New Zealand anymore without someone sniggering and saying ‘Nek minnit!’ I imagine this guy has some regrets.

REGIONAL DIFFERENCES IN RHYME

For me, as a native speaker of New Zealand English (now mixed with Australian), Lynley Dodd is a master of rhythm and rhyme. However, I have it on good authority that English speakers from other parts of the world don’t find Lynley Dodd’s rhyme so perfect. This is an excellent example of how rhyme does not translate perfectly across regional dialects, even in the hands of an expert writer. Every dialect puts emphasis on different words.

- PERIOD — 1980s

- DURATION — 20 minutes or so? The book takes about five minutes to read.

- LOCATION — New Zealand. I believe the author was living in Wellington at the time, but this looks too flat to be Wellington. Hairy Maclary From Donaldson’s Dairy could be set in any number of smaller New Zealand towns.

- ARENA — Hairy Maclary does a ring-route, starting and ending at his own house.

- MANMADE SPACES — What makes this distinctively New Zealand? The fences, I feel. New Zealanders fence their properties off.

- NATURAL SETTINGS — Also the plants. Lynley Dodd is a keen gardener. I don’t know what half these plants are called, but I bet she does.

- WEATHER — A beautiful, utopian day without much wind by the looks of things. (More evidence against a Wellington setting.)

- LEVEL OF CONFLICT — Classic cat and dog conflict. It’s tribal. For an older audience and a different genre, these dogs are in a gang. They meet the leader of the rival gang.

- THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE — Hairy Maclary goes out ‘for a walk’, with no conscious purpose. But we know he’s out looking for interesting smells and company. These dogs are not anthropomorphised. They feel like authentic dogs, and dogs are driven by basic desires. Sometimes I swear dogs love to be scared by things, though, same as two-year-olds reading books exactly like these. Hairy would be delighted to meet the cat.

CUMULATIVE STORY STRUCTURE OF HAIRY MACLARY FROM DONALDSON’S DAIRY

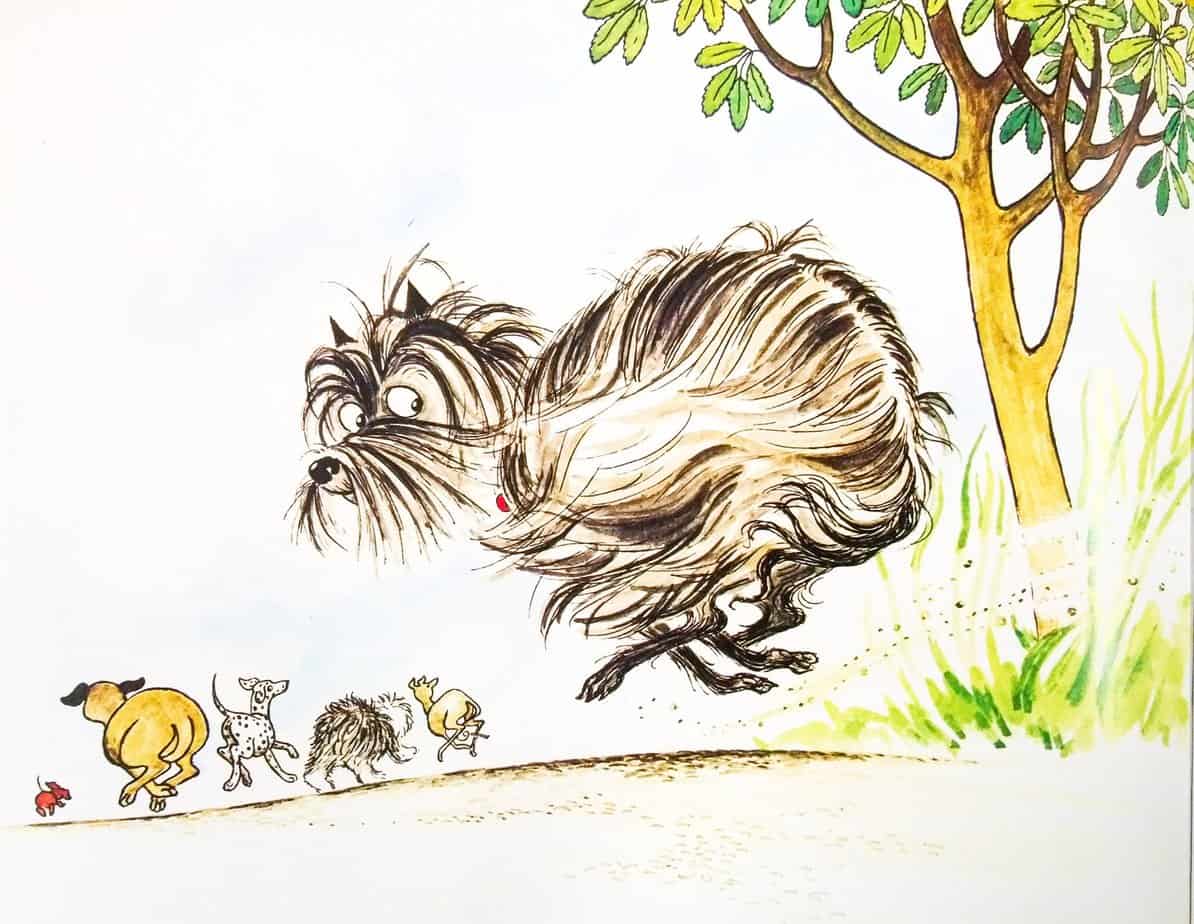

Hairy Maclary goes off for a walk in town, followed by a few friends. All is uneventful until they meet Scarface Claw, the toughest tom in town, and run for home. The story is told by a brilliant, cumulative rhyming text and terrific pictures.

MARKETING COPY

Hairy Maclary is your absolute classic cumulative tale. The structure is very simple. The more simple it is, the harder it is to pull off.

It’s only 32 pages for a children’s picture book so it doesn’t look like a lot of work but it is because the fewer the words, the harder the job really.

Lynley Dodd

I believe the cumulative structure is a simplified version of carnivalesque structure. Lynley Dodd will make use of carnivalesque structure in subsequent stories in the same series, and also sometimes makes use of mythic structure. But she started off with your classic cumulative tale.

PARATEXT

TITLE

Researchers have studied titles of books and come up with a taxonomy of functions titles must fulfil in order to be effective.

Hairy Maclary from Donaldson’s Dairy is a great example of a title which makes use of rhyme and alliteration in order to fulfil its appellative function. (Basically, this means the rhyme and alliteration make the book seem appealing.)

An Every Child is at Home

Hairy Maclary literally walks out of the gate. Many, many children’s stories start with a kid literally gazing out of a window or sitting on a fence, or straddling a fence. Note how important fences are in this story. For dogs especially, a fence is the difference between freedom and captivity, and from the dog’s-eye-view of the world, fences are pretty much everything.

The Every Child wishes to have fun.

For an animal character, this is assumed and deduced.

Disappearance or backgrounding of the home authority figure

For thirty years, Lynley Dodd kept humans right out of the picture. We see their feet and legs, we see them from a distance sometimes, but never their facial expressions. However, she recently created a Hairy Maclary story which includes faces. For readers accustomed to earlier stories this was a shock. Why did she do that?!

Dodd has explained the reason in interview. Basically, she realised the story wouldn’t work unless she showed human reactions.

But there are no human faces in this one. Lynley Dodd does everything with dog eyes, which she depicts as human eyes (with large whites). It’s very difficult to show facial expression in animals without this modification. I mean, dogs don’t even have eyebrows. (Either that or they’re covered in one massive, extended eyebrow.)

Appearance of an Ally in Fun

One by one, the dogs find gaps in the fence. The reader can see dog paws enter the frame before Hairy Maclary does, turning the book into a toy book (with the Where’s Wally ‘can you see it’ element).

Another book which uses this exact technique, and makes the absolute most of it: I Went Walking written by Australian author Sue Williams, illustrated by Julie Vivas (1989).

Hierarchy is overturned. Fun ensues.

The dogs walk around town sniffing whatever they want. No one stops them.

Fun builds!

The ‘build’ comes from the increasing size of the pack. The story is fun to read because the names of the dogs are so satisfying to say.

Peak Fun!

Hairy Maclary (presumably) collects all of his friends, though I feel sorry for the dog who was left out (if these was one!).

Surprise! (for the reader)

The appearance of Scarface Claw!

Return to the Home state

Hairy Maclary runs home. He’s clearly a bit slower to catch on, because all of his friends have a decent head start on him.

RESONANCE

In the 1990s Hairy Maclary was made into a cartoon, narrated by Miranda Harcourt. Lynley Dodd has remained wary against offers to make a Hairy Maclary film. I don’t blame her. I’ve seen Winnie the Pooh and Cat In The Hat. Abominations. I’m pretty sure a feature-length movie is a terrible, terrible idea and I hope whoever inherits Lynley Dodd’s estate will feel the same.

SEE ALSO

Dame Lynley Dodd: the inner workings of Hairy MacLary, an interview with Kim Hill at Radio New Zealand.

A note about this interview. It’s not startling to me at this point, but people get themselves worked up about kidlit academics who conduct research into picture books, especially when their research involves gender. Near the end of this interview, Kim Hill asks Lynley Dodd how she feels to have been included in an international study, which calls picture books out for regressive gender stereotypes.

First of all, Kim was clearly hoping for outrage, if not from Lynley herself (who gave more of a ‘pfft’, reply) then from people like ‘Bruce’, who texts in to say, “Don’t worry about those gender lefties” or something to that effect. Lynley says, “Thank you. Glad to hear I have support.”

Yes, Bruce, but what are your other politics, I don’t wonder.

Here’s the thing. Academics, and people like me at this blog, are filling a specific role in the world of literature. Personally, I’m glad there are academics keeping an eye on children’s books. It used to baffle me why authors themselves get so worked up about research. (Lynley Dodd is gracious, but I’ve seen it in others, and have heard from one or two of them myself.) These other authors consider their own work sacred. They know not to jump onto Goodreads and have a go at that parent who gave them a one star consumer review for their picture book, but academics (who put a lot more time and thought into analysis — more than any consumer reviewer) are not afforded the same grace. If an author took issue because an academic got something wrong, that would constitute healthy debate. It’s not that. It’s,”how dare they analyse my work and come to that conclusion”. We can’t have it both ways: Picture books are important! Leave it alone, it’s just a picture book!

As a creator myself, I understand why it happens. If authors were to let themselves care about academic reactions to their work, the analytical process of doing a count up of, say, gender messages in their animal characters would stymie their creative process. Outright dismissal is a defence mechanism. Plus, no one likes to admit they’ve absorbed problematic cultural messaging. We all like to believe we are rational people who are doing good in the world without subconscious interference. Authors, unfortunately, may be in a special category who love to think of themselves as untouchable outsiders. Authors do think differently, which is why they found success as authors.

I would encourage authors to step back from their own work and gracefully accept, if asked, that academics (and bloggers) fulfil a valuable role.

Interviewers? Stop asking authors to have an opinion on other people’s opinion of their work. For their own creative purposes, authors have no choice but to remove themselves from all that.