“Hairball” is a dark and playful short story by Margaret Atwood. If you dare, find it in the Wilderness Tips collection (1991). Don’t read while eating.

We still think of a powerful man as a born leader and a powerful woman as an anomaly.

Margaret Atwood

When women let their hair down, it means either sexiness or craziness or death, the three by Victorian times having become virtually synonymous.

Margaret Atwood

WHAT HAPPENS IN “HAIRBALL”?

A journalist called Kat has returned from London back to Toronto as head of a new fashion magazine. The “hairball” of the title is a benign tumour she keeps on her mantelpiece as gory memento and talisman.

She’s having an affair with her married boss. Kat doesn’t think much of his wife, who appears a contented housewife. Kat is a career woman. Her job is her life.

She’s also risqué. She has trouble getting her ideas past the conservative men who run the magazine, ironically called “The Razor’s Edge”, since it’s hardly on the vanguard of culture when Kat can’t get her relatively benign ideas past anyone.

Eventually she’s laid off. She loses her big income. She also loses her lover, now her former boss, who has gone back to his wife.

Kat is now left with nothing but bitter resentment. So she exacts a twisted form of revenge on someone who’s done her no wrong.

If you haven’t read the actual story yet, go away and read it.

WHAT IS A TERATOMA?

Anyway so don’t Google it. Do not Google image it.

Though not named in the story, the thing in the jar is a teratoma, which in Greek means ‘monstrous tumour’.

Teratomas can grow teeth, not through dark magic, but through the normal magic of germ cells — the type of stem cell that turns into an egg or sperm cell, which in turn can produce a fetus. Germ cells are “pluripotent,” as scientists put it, which means they can produce all different types of tissue.

Tumors Can Grow Teeth at Discovery

It makes sense that teratomas happen in ovaries, the centre of human reproduction. They can also happen in men. (The testes). Where they grow in children, it’s near the tail bone.

WHAT IS “HAIRBALL” BY MARGARET ATWOOD ABOUT?

Gory plot points aside, what kind of feminism is this? A highly unlikeable main character has an affair with another woman’s husband. When the lover leaves her in the lurch, instead of exacting revenge on the husband, she does something awful to his wife.

First, what is a feminist story? Is it a story in which all the women are nice to each other? A story for and about women? A story which passes the Bechdel Test?

That’s not how I think about fiction. There’s no such thing as a ‘feminist text’, only a ‘feminist reading of a text’. An irredeemable misogynist would read “Hairball” and snigger, “Yeah, that’s women for you. Crazy.”

Another few points:

- In fiction as in real life, women are expected to be likeable. A female fictional character will be experienced as unlikeable more readily than a male character. This ‘likeability gap’ is a long-standing feminist issue and this is Margaret Atwood doing what Margaret Atwood does: Going against expectations. Kat is a modern witch archetype.

- If we apply a feminist lens to this text, “Hairball” is a contemporary take on that hoary old distinction between “marriageable” and “unmarriageable” women. also known as the Madonna/Whore dichotomy. This stale story is as old as the hills and The Harlot’s Progress mythological journey was ridiculously, surprisingly popular until about a hundred years ago. (Since I wrote a whole post on that, no need to repeat it here.) In “Hairball”, the untameable woman isn’t punished. She’s the one doing the punishing.

- Women are expected to be caregivings. Nurturing. Well, what’s the opposite of nurturing? What’s the opposite of ‘giving a part of yourself in service to the care of others’? (Answer: This.)

- What, then, are we to make of Kat’s revenge against another woman, for crying out loud? Why, Margaret? Why? Again, let’s apply a feminist lens. This is how patriarchy works. Patriarchy blames women for everything. Women as well as men internalise the rules of patriarchy and instead of blaming patriarchy — and the (relatively few) powerful men at the top who enforce it — women also blame other women for systems which keep the gender hierarchy in place (with men at the top). Margaret Atwood is trusting readers to understand this basic fact of human culture. Because of course Kat punishes the wife. It’s far too dangerous for her, psychically, to blame the lover who just ditched her. Also, the married housewife with the husband and his stable income represent hegemonic femininity. Kat is revolting against that.

There’s a reason why there’s a million ways that women are taught to hate each other: we are so much stronger, and so much better together.

@emrazz

FEMINIST SYMBOLISM OUT THE WAZOO

In another short story from the Wilderness Tips collection, a husband declares to his wife that men need their meat for haemoglobin purposes. The wife keeps quiet because they are eating dinner, and if she were to counter his declaration with the reality that women are also people, also have haemoglobin and also lose blood every month due to menstruation, that would ick him out.

So Margaret Atwood was clearly exploring and challenging the default position of men: That female bodies are disgusting.

This story essentially looks at the link between what’s seen as “disgusting” about female bodies, and their violation of accepted societal roles. The description of the benign ovarian cyst the protagonist takes home in a jar of formaldehyde to exhibit on her mantelpiece was “gross” enough to drive my partner from the room when I read it aloud, further proving Atwood’s point.

consumer review

Feminist discourse happening around this time had been talking about this very issue, and one of the best (most depressing) accounts I’ve read of why men find women disgusting was written by Marilyn French (1929 – 2009) in her book Beyond Power: On Women, Men & Morals, first published in 1986. (French is most famous for a different book, The Women’s Room.)

This examination of the nature and effects of power draws on the wide range of disciplines, including anthropology, history, political science, law, and theology—to investigate the sources of patriarchy

In a 1992 interview, Marilyn French is asked, “Do you think now, the women [writers] are as important as the men?” Like Margaret Atwood, Marilyn French uses an eating metaphor when talking about power:

I think [women are] more important. I think that the important literature of a period comes from people who are hungry. I mean in the deepest sense, hungry. I think in the United States, for instance, the most important wave of literature is coming from Black women. Because they need to express themselves. They’re hungry for a voice. They’re producing wonderful, wonderful stuff. And I think what women are producing these days is very much alive.

Marilyn French

Notice how, like Atwood, French uses the word ‘alive’ to describe artistic output rather than something which is literally alive in the living, breathing sense.

In an earlier, 1987 interview on a BBC talk show called Wogan, the middle-aged white man interviewer asks, “Now, The Women’s Room didn’t paint men in tremendously glowing colours. You certainly paint them as exploiting women. Was that drawn from observation or from your own experience?”

(If it’s not immediately apparent to you how awful and gendered that question is, I highly recommend the darkly humorous feminist text How To Suppress Women’s Writing by Joanna Russ.)

Marilyn French replies, with only the faintest flicker of eye-roll:

“[The Women’s Room] was drawn from observation, but observation is one’s own experience, especially if you’re a woman. I mean, you do, when raising children sit around the coffee table and talk to your friends. And you hear their stories and that becomes part of your own life. Women have close communities. I don’t know how many women’s stories I must have heard in my lifetime. Hundreds. And that line is in the book: I’ve swallowed all these women’s voices. They are in my head.”

Terry Wogan later asks, belabouring the point, “You don’t think it’s the natural instinct of a mother? To take care of a baby in her arms?”

Marilyn French explains that women take care of children because they take responsibility, not because women have access to some hormone which magically compels them towards nurturing others.

A BRIEF NOD TO FREUD

Who had many weird things to say with a few genius insights:

For Freudian critics who want to discover what is inside a character, “Hairball” presents a hidden self brought to light. […]

Strangers Within the Gates: Margaret Atwood’s Wilderness Tips by Carol L. Beran

INCONGRUOUS SLAPSTICK COMEDY

Hairball, who is benign only in the doctor’s diagnosis, invades Kat’s body and the party held by Ger’s wife. The potentially slapstick comedy of the untold opening of the truffle box containing the tumor is funny because of its incongruity. But Kat’s behavior—which readers sympathetic to Kat’s predicament applaud—is not polite; it not only joyously transgresses the Canadian code of good manners, but also violates the biblical injunction, “Be not forgetful to entertain strangers: for thereby some have entertained angels unawares” (Hebrews 13:2, King James Version), satirizing two cultural beliefs.

Strangers Within the Gates: Margaret Atwood’s Wilderness Tips by Carol L. Beran

COMEDY AS A VEHICLE INTO ANGER

The three stories of very strange strangers offer a key to reading this book: rage. The words “rage,” “outraged,” “anger,” and “angry” recur throughout Wilderness Tips. In “Hairball” Kat wants to name a magazine “All the Rage,” but “the board was put off by the vibrations of anger in the word ‘rage’”; she later writes of Hairball disguised as a truffle, “This is all the rage“.

In “Hack Wednesday,” Marcia remembers “when airlessness was all the rage”. The waitresses in “True Trash” are “outraged” at a story. Donny in “True Trash,” Richard in “Isis in Darkness,” and Lois in “Death by Landscape” are described as “angry”. Susanna feels “anger” in “Uncles”. […]

The exaggeration of the interloper clashes with the diminution of the Canadian to produce a kind of humor that, in spite of its understated tone, should make the reader angry about the way things are.

Strangers Within the Gates: Margaret Atwood’s Wilderness Tips by Carol L. Beran

THE CLIMACTIC OVARY-CHOCOLATE-TRUFFLE SCENE

Cannibalism: when people eat people. Auto-cannibalism: when people eat parts of themselves.

This story contains neither, because we don’t expect anyone to actually eat Kat’s ‘gift’. But we can still talk about Margaret Atwood and cannibalism, because this plot is an example of metaphorical cannibalism: Body part presented as something to eat.

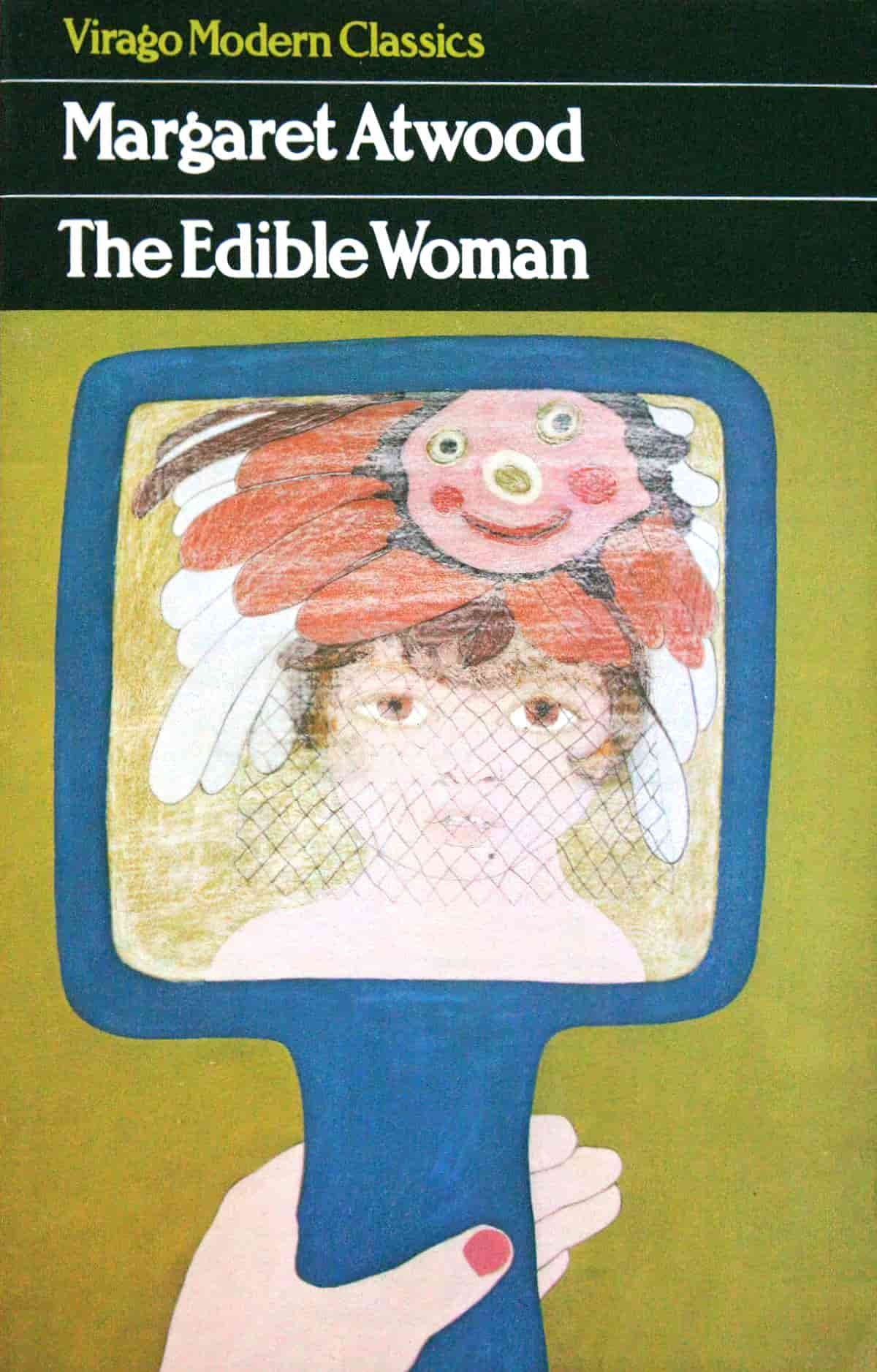

Cannibalism characterizes Margaret Atwood’s dystopias. She’s famous for her interest in who eats who. her debut novel, The Edible Woman (1969), is about emotional and social cannibalism.

Marian is determined to be ordinary. She lays her head gently on the shoulder of her serious fiancé and quietly awaits marriage. But she didn’t count on an inner rebellion that would rock her stable routine, and her digestion. Marriage à la mode, Marian discovers, is something she literally can’t stomach…

It follows the story of Marian MacAlpin, a young woman who develops an eating disorder that makes food inedible for her. Through this character, Atwood cleverly shows that the pressures put on women by the society can have severely adverse effects on their bodies and psyches. Despite being written in the late 60s, it is still considered a classic today due to its nuanced approach in terms of composition style and intricate portrayal of the protagonist and her mental taxation.

Social “Cannibalism” and the Edible Women

In conversation with Samira Ahmed at How I Found My Voice podcast, Ahmed points out that Atwood wrote this book before disordered eating was widely recognised, and wonders if Atwood’s time as a waitress (in which she lost her appetite after dealing with the mush on other people’s plates) informed the book. Atwood doesn’t answer directly, but doesn’t disagree with the assessment. (She does mention writing this book on a card table while looking over Vancouver Harbour.)

For Atwood, politics is a metonymy of eating.

Chapter 4 – Food in Margaret Atwood’s Dystopias, 2017

What’s a metonym? It’s a figure of speech: A word closely associated with something else. The word represents that other, broader thing e.g. apron as metonym for housewife.

Margaret Atwood has herself defined what she means by the word ‘politics’. She used eating as metaphor for power:

By ‘politics’, I mean who is entitled to do what to whom, with impunity; who profits by it; and who therefore eats what.

Margaret Atwood in an Amnesty International address published in a 1982 collection of essays

THE LITERARY TONE OF “HAIRBALL”

Margaret Atwood sometimes writes about cannibalism in a serious tone, and at other times playfully. In The Handmaid’s Tale, for instance, she uses cannibalism to remind readers of Hitler-style extermination. In that famous novel, characters eat food reminiscent of female body parts: pears, eggs, chickens and bread. (At first glance ‘bread’ doesn’t sound especially body-party, until you remember the idiomatic expression “bun in the oven” meaning “pregnant”.)

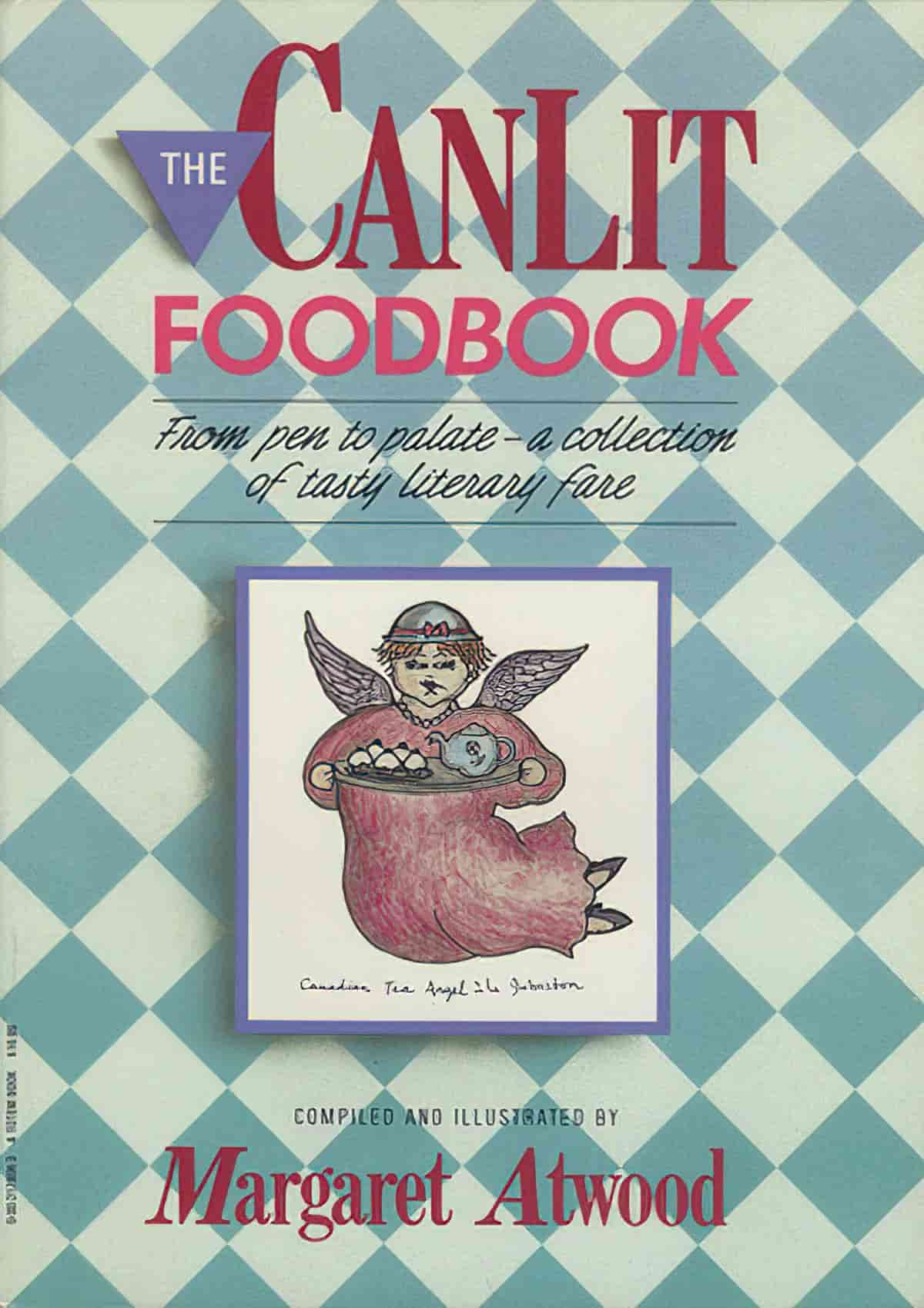

Perhaps Atwood’s most playful treatment comes from something she wrote (and illustrated) as a fundraiser for authors being detained as political prisoners:

Atwood has clearly been fascinated with the idea of cannibalism. She has treated this subject playfully in at least one other context. In 1987 The CanLit Foodbook: From Pen to Palette—a Collection of Tasty Literary Fare, edited and illustrated by Margaret Atwood was published. Written as a fund-raiser for Canada’s Anglophone P.E.N., the book is a compilation of authors’ favorite recipes, and selections from Canadian authors containing descriptions of food or meals. Atwood cautions her readers that this is not exactly a cookbook. Indeed, chapter nine is titled: “Eating People Is Wrong: Cannibalism Canadian Style.”

Margaret Atwood’s Modest Proposal: The Handmaid’s Tale

Chapter nine is devoted to cannibalism, metaphorical and actual, of which there’s a surprising amount of Canadian literature. It appears to be one of those thrill-of-the-forbidden literary motifs, like the murders in murder mysteries, that we delight to contemplate, though we would probably not do it for fun, except in children’s literature, where devouring and being devoured appears to be a matter of course.

Margaret Atwood in the foreword to The CanLit Foodbook

And where does “Hairball” sit, tonally? Does this feel playful to you, or dark? For me, the tone changes as the meanings behind the story become apparent. The title, “Hairball”, is clearly playful. A hairball is harmless, right? You can’t get much more harmless than a literal ball of hair.

This short story gets darker and darker in tone. It never lets up. This is one woman’s descent into madness, but madness is a version of empowerment. A madwoman is powerful because she’s no longer bounded by feminine gender rules.

MARGARET ATWOOD’S THOUGHTS ON BEING A CANADIAN IN LONDON

TYLER COWEN: When you were living in London — I think this is after Alberta — were you ever tempted just to stay there and be part of the London literary scene?

MARGARET ATWOOD: No.

COWEN: Why not?

ATWOOD: Because I’m not British.

COWEN: But people often move countries.

ATWOOD: They do.

COWEN: It’s probably easier to earn a living as a writer in London.

ATWOOD: No, I don’t think so. I love going there and making fun of them. So, no. I have lots of fun, but living there would be a different type of thing.

I remember when I first went there, Canada was very low on the totem pole of what you took seriously as any sort of artistic thing. People really would say to me, “Canadian literature — isn’t that an oxymoron?” Or let me do it correctly [with upper-class British accent], “Canadian literature — isn’t that an oxymoron? Ho, ho, ho.”

[laughter]

Margaret Atwood in conversation with American economist Tyler Cowen (2019)

MARGARET ATWOOD ON WOMEN WHO DESPISE OTHER WOMEN

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Hi, Ms. Atwood. Thank you very much for being here. I wanted to ask you . . . You are very special in that throughout your work, especially your novels — Cat’s Eye, Robber Bride, even The Handmaid’s Tale, even though it goes unnoticed — you portray the cruelty and psychological manipulation that women inflict on one another.

I wondered, in your opinion, why mainstream progressive feminism today can’t seem to acknowledge the role of intrasexual competition in the lives of the oppression of women?

ATWOOD: You mean woman-woman?

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Yeah.

ATWOOD: I don’t know. Because they’ve forgotten grade four. I think it’s an ideological thing, that it’s a piece of ideology that says this shouldn’t happen, and therefore we’re not allowed to say that it does happen.

But you know, essentially women are people, just like other people. That means that there’s a wide variety, and there are different degrees of aggression and dominance and so forth amongst them. And there are power struggles. That’s just like people. So why be surprised? And why try to pretend it doesn’t happen? It’s kind of not the point. Women don’t have to be perfect in order to have rights.

If men had to be perfect in order to have rights, they wouldn’t have any rights. It’s not perfect. Women aren’t perfect either, and they shouldn’t be expected to be perfect any more than anybody else.

It’s really a pretty simple story, and even if you get a quite heavily invested ideological female person — if you go back in her past, you will find a moment in her life when some other female person wasn’t totally nice to her. It happens. So what? It doesn’t mean that women aren’t worthy of having rights like other people.

Margaret Atwood in conversation with American economist Tyler Cowen (2019)