It’s stating the obvious to point out that, in children’s fiction, a character’s hair maps onto personality. But in continuing to use hair-personality shortcuts, are writers perpetuating stereotypes?

Canadian teen actor Sophie Nélisse plays the title role, a young girl in foster care who we know is not terribly well-off emotionally because her hair is so flat. Her attitude stinks, too.

review of the film adaptation of The Great Gilly Hopkins

As is usual for matters of appearance, this post applies mainly to girl characters. The hairstyles of boys are far less commonly attached to their personalities, desires and psychological shortcomings.

Some authors, such as Daniel Handler, avoid mentioning how a girl looks in books. We didn’t know what Violet looked like until Netflix adapted A Series Of Unfortunate Events for screen. (We only knew that Violet had long hair because she does something with the bow on it.)

The distinction between ‘inborn’ and ‘styling choices’ of a character is important:

Anyone who has read a book is likely familiar with this phenomenon. Characters’ hair, for example, is often written as a remarkably accurate reflection of their personalities: feisty heroines are endowed with hair as sassy as they are, and these ‘wild manes’ subsequently spend every scene ‘struggling to escape’ from hair ties, messy buns, or other oppressive hairstyles. Granted, a green mohawk may imply a certain individuality of temperament, but self-styling can at least be controlled—this is very different to insinuating that because a person is born with curly hair, they’re automatically incapable of keeping their temper. Worse still is when this descends into racial stereotyping.

ACT Writers Blog

Black girl magic takes the solar system in Stella’s Stellar Hair , a celebration of hair, family, and self-love from debut author-illustrator Yesenia Moises!

It’s the day of the Big Star Little Gala, and Stella’s hair just isn’t acting right! What’s a girl to do?

Simple! Just hop on her hoverboard, visit each of her fabulous aunties across the solar system, and find the perfect hairdo along the way.

Stella’s Stellar Hair celebrates the joy of self-empowerment, shows off our solar system, and beautifully illustrates a variety of hairstyles from the African diaspora. Backmatter provides more information about each style and each planet.

‘WILD’ HAIR

Naturally non-straight hair is also described in fiction as kinky or curly.

Wild hair can mean: A free spirit, pluck, individuality, fun.

Quite often it means all of those wonderful things AND it means the girl is in need of some serious calming down. Messy-haired girl will undergo a character arc over the course of the movie in which she learns to be nice to people and appreciate family. Especially if this is a screen story, the girl’s hair will change to show us that she has been tamed.

This happens in the film adaptation of The Great Gilly Hopkins for instance, in which Gilly gets a very becoming new hairstyle at the end. In the final dinner party scene Gilly has her hair tied back, a pony tail carefully constructed to sit to one side and neatly parted down the middle.

Does anyone else interpret compliments on your haircut as attacks on your previous hair?

@studiesincrap

RED HAIR

Less than 2 per cent of the population has red hair. Most have Irish or Scottish ancestry.

In early modern England it was thought that if a woman had sex during her period, this would result in a puny baby with red hair — both undesirable attributes.

Red hair is also connected to witchery — in earlier times literally, and now mostly in stories. See for example Badjelly The Witch.

There’s a damn good reason why Anne Shirley wants black hair, and it’s not about vanity. She’s trying to avoid some very real discrimination. Anne’s life would really have been easier had she been born with non-red hair. Especially at that cultural moment, a girl with red hair was thought to have a bad temper. It was a form of actual discrimination and I don’t believe it’s truly died. I doubt we really think ‘witch child’ when we think red hair anymore, but that wasn’t true in L. M. Montgomery’s time. The concept of ‘wickedness’ and ‘evil’ run strong through the Green Gables series.

Picture book illustrators love red hair. Though I haven’t made a formal study, there is absolutely a disproportionate number of red-headed children in picture books and I suspect the reason is simple: red is an excellent focal point and attracts attention to the main character on the page.

Other memorable red-heads:

- Amelia Bedelia

- Fancy Nancy

- Caddie Woodlawn

- Madeline

- Pippi Longstocking

- The Weasleys in Harry Potter

- Eleanor (and Park)

- Olivia from The Year Of Shadows

- Paige from Paige by Page

- Gwinna

- Tina Blake from Carrie by Stephen King

Most TV shows with a large cast of characters will feature a redhead for visual interest and distinction.

- Bree of Desperate Housewives

- Joan Holloway of Mad Men

- Claire Fisher of Six Feet Under (probably one of the few natural red heads on TV)

- Willow on Buffy — also Oz of the male characters

- Daphne of Scooby Doo

- Francie Jarvis of Gilmore Girls

- Todd of Breaking Bad, partly to distinguish him from an otherwise indistinguishable gang of baddies. Though a friend of mine tells me he is definitely not a red head. He is a ‘strawberry blonde’.

Red hair, or lack of pigmentation around the eyelashes and eyebrows (be they red headed or strawberry blonde), is mostly used to show that a character is different. Since they will always stand out in a crowd owing to their pigmentation, they might as well step right out of normality, right?

Sometimes, as in the Bree of Desperate Housewives case, the red doesn’t seem to stand for anything in particular, but is a stylistic choice, to individuate characters from one another. There are already two main blonde women, so Bree had to be different. In Bree’s case, you could argue that the redness of her hair marks her out as evil, deriving from witch folklore. Bree is cold and calculating and always composed. Red haired characters are just as likely portrayed as not in control of their emotions (the Anne Shirley trope). Bree and Anne represent to extremes on the same spectrum.

Prejudices against people because of the colour of their skin are unacceptable. And yet, it is often socially accepted to make fun of people because of the colour of their hair. Why should this be any different? And is there any evidence to back up the beliefs?

In this episode Mark Norman, the creator of The Folklore Podcast, discusses the beliefs, superstitions and folklore attached to those sporting red hair.

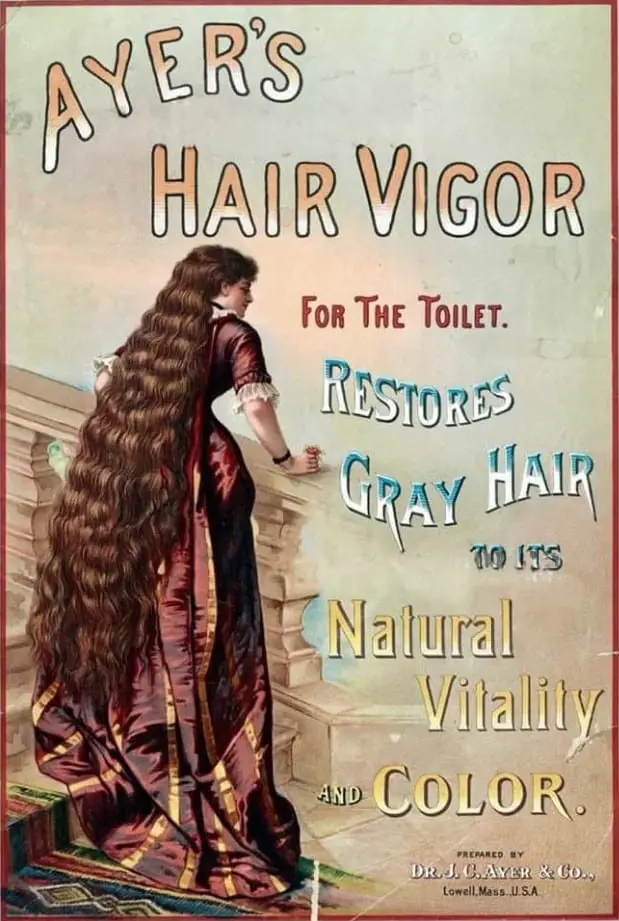

PERFECT HAIR

I judge television shows by the women’s hair. It turns out this is a binary judgment: Either the women have TV hair, or they don’t. What is TV hair? It’s shiny, long, has obviously been styled with a curling iron at the ends, and looks like that of a beauty pageant contestant. […] the less sleek the hair, the more likely a show will have a memorable female protagonist

The NYT Style Magazine

The girl opponents in middle grade/chapter books all seem to have perfect hair, even if they’re an opponent at first and then turn out to be besties, because ‘we shouldn’t judge others by what they look like’.

NO HAIR

The “Mother’s Day” episode of Courage The Cowardly Dog offers viewers the backstory of Eustace Bagge. When we see his mother is the female equivalent of her son, and that she mistreats Eustace the way Eustace mistreats Courage, we understand why Eustace behaves the way he does.

The ultimate gag in this episode is that, after preening herself, old Mrs Bagge is humiliated by losing her wig. It is revealed that under her accoutrements she looks exactly the same as Eustace. Without her hair, Mrs Bagge sobs that she is ‘ugly’ and that nobody could possibly love her. Eustace and his mother end up reconciling, rubbing each other’s billiard ball heads lovingly. They have realised how similar they are, and that loving each other means loving themselves.

While the implication is that true family will love you no matter what you look like, the other, inevitable implication is that having a full head of luxurious hair makes a woman beautiful. Lack of hair is connected to Eustace’s ugliness, too. But the difference is, he does not feel great shame about this. An absence of hair signifies:

- In old men, old age

- In younger men, toughness

- In women, ugliness, lack of sexual desirability

No surprises there, perhaps.

Writers, is it possible to subvert these tropes? Red-headed kids who are totally normal, and neither witchy nor out of control? The bookish kid with curly hair? The bookish girl who also happens to have messy hair? (Actually pretty common in real life.)

Alternatively, should we all make like Daniel Handler and refuse to describe child characters more than we absolutely must? When writers avoid talking about appearance, child readers get to see themselves as the hero. In Handler’s case he decided not to describe Violet because he realised girls have an undue amount of attention foisted upon how they look and he didn’t want to add to that corpus. I applaud him for that. Instead, all we know about Violet (in the books, at least) is that she ties her (long) hair up before doing something physical.

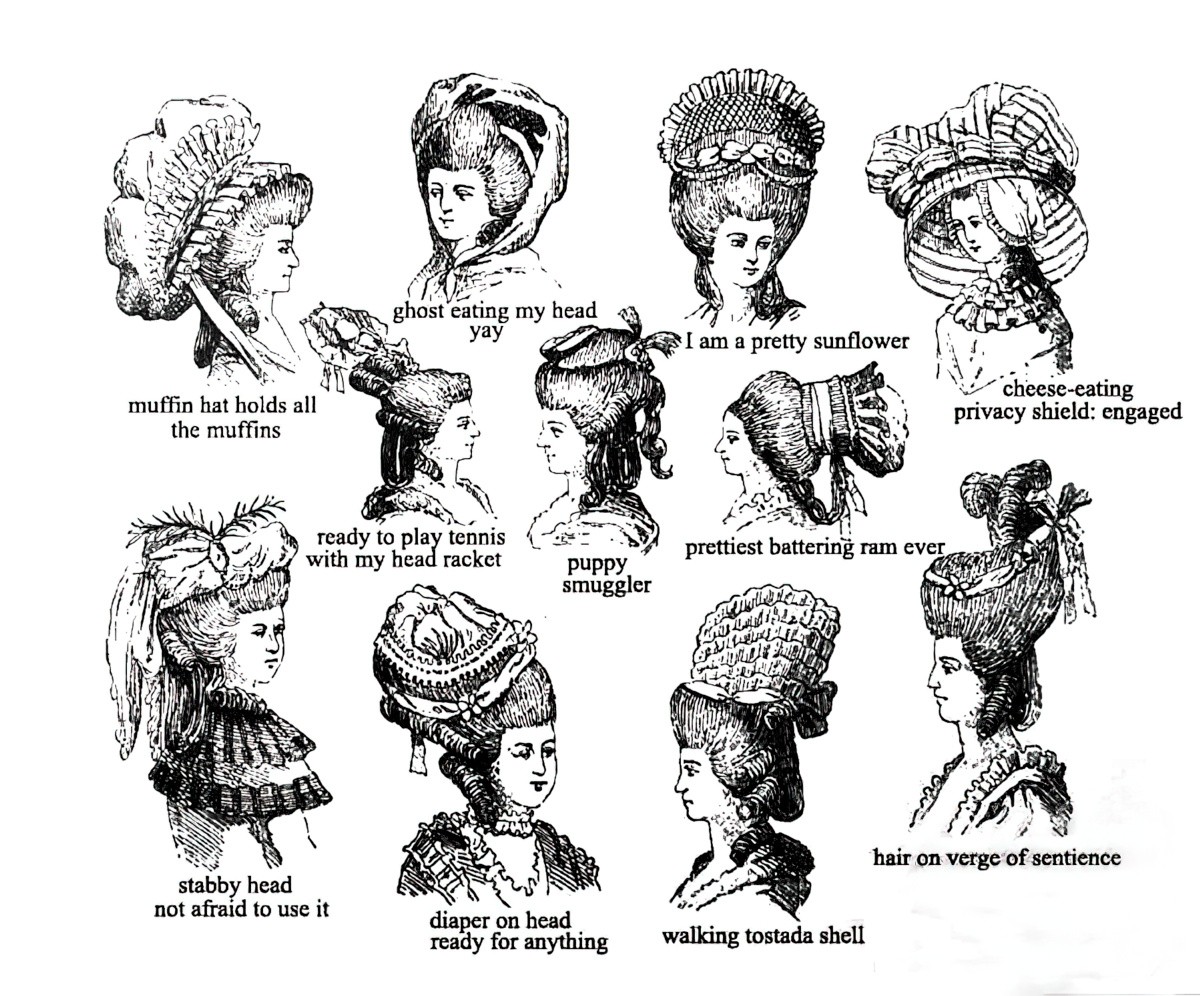

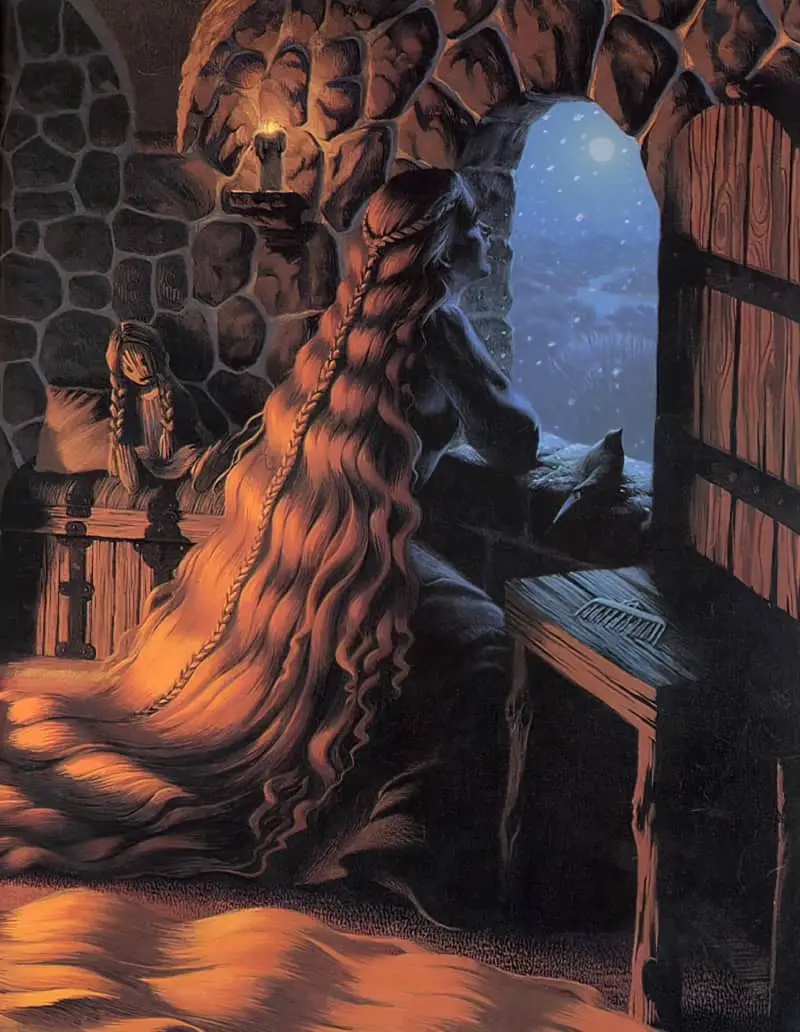

HAIR IN FAIRYTALES

In fairytales, characters alternate between states of enchantment and disenchantment. Symbols and tropes indicate which state a fairytale character is in at any given time. For instance, if a heroine on the cusp of puberty is wearing a ragged fur or skin, taken by lunar creatures (dragons, werewolves) or transmogrified into snakes (etc), blind or mute, she is in a state of enchantment.

A fairytale heroine can disenchant herself by: shucking off her ragged fur, escaping from the dragon’s lair, turning back into a human and defloration.

Less intrusively, she might also comb or brush the tangles out of her dishevelled hair. If dishevelled hair in fairytales means ‘under some kind of spell’, how does that translate in modern stories? A femme-coded character with messy hair indicates some sort of disarray or erraticness. The state of a girl’s hair is thought to say something about her personality. Messy hair, crazy.

BLACK HAIR, WHITE HAIR

The title for this section comes from the old Western genre trope of white hats versus black hats, in which the guys with white hats are the goodies.

The idea of black hair as a female symbol of evil and power is illustrated perfectly by Rachel Wise:

If the witch and the fatal woman have functioned over the centuries as warnings to women who might be tempted to act autonomously or enjoy their own sexuality, the beautiful brides of hero tales have compounded women’s psychological oppression by providing a model of what they ‘ought’ to look like—in appearance, attitude and behaviour. This model has profoundly influenced women’s perceptions of themselves and has contributed to their pervasive self-lingering belief that it is natural for women to be submissive and self-denying, sacrificing their interests to the needs of the men in their lives.

It is hardly necessary to describe the physical attributes of the hero’s bride as her late twentieth-century incarnations smile at us every day from advertisements, fashion magazines, film and television screens, but a consideration of the significance of her appearance is instructive. She is, of course, beautiful; in one of the most popular fairy tales ‘Beauty’ is her only name. But her beauty is of a particular kind, and advances in the technology of printing and the reproduction of works of art, together with the advent of film and television, have made the visual definitions of Western female beauty as familiar as the motifs of the hero story itself. …

To begin with the bride is white, and usually blonde. In fairy tales golden-haired beauties abound; the only memorable dark-haired heroine is Snow White whose hair is in stark contrast to the pallor of her skin. Rapunzel is more typical: she had ‘long and beautiful hair, as fine spun as gold’, which she let down from her tower window to allow the witch and the prince to climb up. … The story of ‘Goldilocks and the Three Bears’ did not become popular until the late nineteenth century when it was modified to emphasize the golden hair.

Marjery Hourihan, Deconstructing The Hero

Hourihan also explains that even when the blondness of hair is not mentioned in picture books and illustrated stories, the illustrator often gives the ‘beauty’ blonde hair anyway, such is the power of the trope. Cinderella has had golden hair since 1854, courtesy of illustrator George Cruickshank.

See also

The Betty and Veronica Trope explained with numerous examples.

The blonde-hair is better than brown-hair idea continues to be perpetuated, as recently as Laura Ingalls and Ramona Quimby, both of whom despise their own brown hair, wishing it could be blonde.

Since Ramona, middle grade realistic fiction aimed at girls has created a slightly different hair-related trope: The blonde girl as goody-two-shoes who at some point has to be punished for being so fussy about her willingness to please and her pretty dresses. A true, relatable heroine of middle grade fiction is more of a ‘tomboy’.

(Tina Fey addresses it in her autobiographical book Bossypants, and explains that as a child she noticed that blonde girls get all the attention.)

THE TOUPEE

A wonderful character study below, introducing a man by talking about his relationship to his toupees:

Sunny Siberia

1

When you entered the executive offices of Mercury Pictures International, you would first see a scale model of the studio itself. Artie Feldman, co-founder and head of production, installed it in the lobby to distract skittish investors from second thoughts. Complete with back lot, sound stages, and facilities buildings, the miniature was a faithful replica of the ten-acre studio in which it sat. Maria Lagana, as rendered by the miniaturist, was a tiny, featureless figure looking out Artie’s office window. And this was where the real Maria stood late one morning in 1941, hands holstered on her hips, watching a pigeon autograph the windshield of her boss’s new convertible. She’d like to buy that bird a drink.

“It’s a beautiful day out, Art,” Maria said. “You should really come have a look.”

“I have,” Artie said. “It made me want to jump.”

Artie wasn’t known for his joie de vivre, but he usually didn’t fantasize about ending it all this close to lunch. Maria wondered if the Senate Investigation into Motion Picture War Propaganda was giving him agita, but no—the crisis at hand was on his head. His bald spot had finally grown too large for his toupee to conceal.

Six other black toupees were shellacked atop wooden mannequin heads on the shelf behind his desk, where a more successful producer might display his Oscars. They were conversation starters. As in, Artie began conversations with new employees by telling them the toupees were the scalps of their predecessors.

As far as Maria could tell, the six hairpieces were the same indistinguishable model and style, but Artie had become convinced that each one crackled with the karmic energy of the hair’s original head, unrealized and awaiting release, like a static charge smuggled in a fingertip. Thus, he’d named his toupees after their personalities: The Heavyweight, The Casanova, The Optimist, The Edison, The Odysseus, and The Mephistopheles. Artie had never felt more at home in his adoptive country than when he learned the Founding Fathers had all worn toupees, even that showboat John Hancock. The only one who hadn’t was Benjamin Franklin. And look how he turned out: a syphilitic Francophile who got his jollies flying kites in the rain.

“Maybe the toupee shrunk,” he said, still hoping for a miracle.

“I think you’ll need one with more coverage, Art.”

the opening to Mercury Pictures Presents, a 2022 novel by Anthony Marra

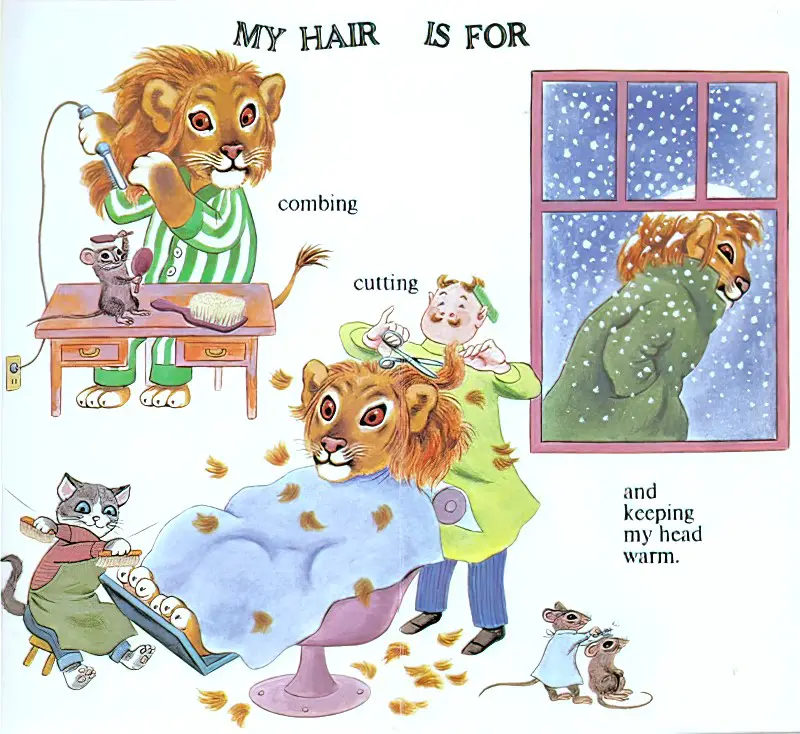

BIRDS AND HAIR

There is a clear association between hair and birds in funny stories especially, whether the hair is attached to a human or a furry animal.