Margaret Atwood has a knack for writing prescient feminist pieces which remain relatable over decades. I wish she wouldn’t. I wish, for once, that Margaret Atwood were wrong about something (in fiction).

“Hack Wednesday” was published in the September 17, 1990 edition of The New Yorker. Or you can find it in Atwood’s Wilderness Tips collection, published the following year.

I feel the underlying theme of this story is: The Personal Is Political, secondwave feminist slogan.

As I read, I noticed how both Marcia and her husband are interested in world matters, but only Eric’s way of interacting with the world is seen as serious and legit. When Eric speaks of political matters, Marcia changes the subject. When Marcia interacts with a workmate she is ‘gossiping’. When she writes her column she is ‘hysterical’ and ‘soppy’.

But in various, subtle ways, Margaret Atwood’s story asks readers to reconsider the gendered divisions between what constitutes ‘family’ versus what constitutes ‘worldly’.

Atwood compares Eric’s politically motivated food restriction to Marcia’s feminised dieting, and Eric’s wish to stop progress (to stop American invasion, to stop the 1989 Free Trade Agreement) to Marcia’s wish to halt ageing. Whereas Eric’s concerns seem worldly, Marcia’s desires are easily dismissed, since women are thought to be motivated solely by home life and babies, despite achieving a small debut into the serious working world of men.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “HACK WEDNESDAY”?

Marcia, a lifestyles and social issues writer for a Canadian newspaper, and who is now middle-aged, has been dreaming about babies as Christmas draws near. Her husband, Eric, ecologically minded and a political reactionary, writes popular history. The grim aspects of the news (Panama, Noriega) reflect themselves in Marcia’s columns about homelessness and child abuse, irritating her editor/boss, and she begins to feel that her days are numbered. At a clandestine lunch with a flirtatious co-worker, Gus, she becomes drunk enough to realize, thinking of Noriega, that the reason she is a soppy writer is that “she does not believe that children are born evil, that she is always too ready to explain. The narration fast-forwards to Christmas Day where, after the festivities, Marcia hides herself in the bathroom hugging her cat, and crying because “she is no longer a child, or because there are children who have never been children, or because she can’t have a child any longer, ever again…. It’s all this talk about babies, at Christmas. It’s all this hope. She gets distracted by it, and has trouble paying attention to the real news.

summary on The Complete New Yorker CD-ROM box set, 2005

THE WORLD OF THE LATE 1980s

For all its relatability, there’s also something very insider-knowledge about “Hack Wednesday”. If you were living as an adult through late 1980s Toronto, you’ll surely get more out of Atwood’s politically charged dialogue. I was a kid back then, living on the other side of the world about as far from Toronto as it’s possible to get. (For context, “The gateway to Antarctica” is my hometown.)

But! We now have the Internet. What can I look up?

GEORGE BUSH AND THE CANADA-US FREE TRADE AGREEMENT; MARCIA AND ERIC

In 1989, George Bush was USA vice president alongiside Ronald Reagan, and later in the year became president.

In “Wednesday Hack” Marcia’s husband Eric is annoyed about the 1989 free trade agreement between Canada and the USA — subsequently replaced in 1994 with the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), this time including Mexico.

Canadians were more affected by this deal than Americans, and were far more aware of it. The Canadian Liberal party had used it to force an election. Also, Canada was far more reliant on American trade than the other way around. Canada worried that America would lump them in with protectionist actions aimed at countries like Japan and the Far East. Canadians had grown suspicious of the many American corporations which had been opening up in Canada over the previous few decades. The Canadian economy had been going gangbusters in the post WW2 19050s and 60s, because high tariffs encouraged Canadian companies making goods on Canadian land for Canadians. That life was on the way out.

In short, many Canadians couldn’t see anything good would come from the 1989 FTA agreement with the USA under Bush. Eric would have felt powerless to stop any of this from happening, and in this story is shown to be wresting back some control by refusing to buy food that hasn’t been grown in Canada. When we learn Eric has given up coffee, we don’t yet know why but we can deduce with delayed decoding that it’s because coffee is an imported product.

Bending to his outrage but also not fully onboard with it, Marcia eats what she likes whenever she’s out on her own, but is never completely free of Eric’s control of her food:

Marcia orders a sangria, and settles her widening bottom thankfully into her chair. Here she can eat imported food without feeling like a traitor. She intends to order blood oranges if she can get them. Those, and garlic soup. If Eric cross-examines her later, her conscience will be clear.

“Wednesday Hack”

She feels guilty for not giving up her morning coffee, so Eric doesn’t have to watch her enjoy it. Marcia doesn’t have full freedom and autonomy in her own home, yet this is nothing unusual. Women of this era were told to carve out their own niches around the needs of men. Here’s Margaret Atwood, slyly pointing it out, inviting readers to piece tenon and mortise together, noticing the build-up of accumulated gender inequalities for ourselves.

Notice how Margaret Atwood depicts a woman with a (mild? culturally sanctioned) eating disorder and her husband with an entirely different sort of restrictive anorexia. Marcia is affected by the newspapers and magazines telling her she’s too fat whereas Eric, as a man, has been acculturated differently: Equally restrictive in his food choices, he believes he is doing it for a greater cause, not out of feminine vanity, Heaven forbid. The difference: Marcia’s own food restrictions affect Marcia. Eric’s food restrictions affect Eric and Marcia. (The same gendered thing applies to so many areas of life. If some horrible thing affects men, you can bet it affects women more, and so on down the social hierarchy.)

Have North American trade agreements been good for Canada, or was Eric correct to worry?

Well, the FTA coincided with high unemployment:

Many Canadian critics felt vindicated in the years following the passage of the FTA, eyeing the contraction of employment across all industries between 1989 and 1993. The Canadian Labour Congress reported the loss of over 250, 000 jobs in the first two years of the Agreement, along with a wave of takeovers of Canadian-based countries. Some commentators, however suggest that the FTA was hardly a crucial factor in these numbers, and attribute them instead to other domestic economic policies like the fight against inflation.

Reference for Business

However! The 1994 NAFTA is described positively. From the Government of Canada website: “NAFTA has had an overwhelmingly positive effect on the Canadian economy. It has opened up new export opportunities, acted as a stimulus to build internationally competitive businesses, and helped attract significant foreign investment.”

NORIEGA

Eric predicts the arrest of Noriega, referring to the military leader of Panama between 1983 and 1989. He helped President Nixon secure military gear. He was a strongman leader who intimidated and harassed others to retain power. He was a drug trafficker.

In 1989 he had cancelled the Panama presidential elections, attempting to rule via a puppet government (which looks independent but is actually run by an outside power).

The USA invaded Panama. America had been trying to mind its own business a bit since the Vietnam War, so this was a massive move. In Atwood’s story, Eric doesn’t approve.

Anyhow, when the US troops turned up in Panama City, Noriega hid in an embassy. The Americans tortured him with rock music until he surrendered. The year after this story was written, he was tried on criminal charges in Miami.

Sure enough, he was convicted of trafficking cocaine, among numerous other evils such as money laundering. He served time in America, was extradited to France, sent back to Panama, then died in 2017.

In the story, Eric uses the word ‘Trots’.

In my dealings with Canadians, I learned as an Australasian that when Canadians say ‘trots’ they do not mean what we mean when we say ‘trots’ as in, ‘I have a case of the trots’.

No, Eric uses ‘Trot’ as an abbreviation of Trotskyist. Leon Trotsky was a Russian-Ukranian Marxist revolutionary, assassinated with an ice pick in 1940 by a contract killer ordered by Stalin.

‘Trotskyist’ or ‘Trot’ is meant as an offensive term (though not always). Its meaning changes depending on who’s using it. In fascist circles, it refers to anyone left of fascism. Others use it to mean someone hopelessly idealistic about communism.

Notice how Eric describes America’s invasion into Panama and could equally be describing how a misogynistic culture invades the brains of women. A mini allegory.

C.S.I.S. (CANADIAN SECURITY INTELLIGENCE SERVICE)

Although he jokes about being the target of spies, Eric’s teasing indicates delusions of grandeur. (The irony is, he declares he’s doing this to make others feel important.) He calls the C.S.I.S. ‘Ca-sissies’, clearly derogatory, because if a man wants to be derogatory, he only needs call someone female (sissy) or gay.

THE GREENHOUSE EFFECT

Ah, yes. I don’t need to look this one up. Children of the 80s remember this well. We didn’t worry about ‘climate change’ in the 1980s. We were taught to put our rubbish in the bin. We were also encouraged to recycle, though there was no door-to-door recycling program set up — if you wanted to recycle you had to visit a special place in town and basically dedicate your life to it.

In “Hack Wednesday,” Marcia has trouble with the cognitive dissonance between ‘the coldest record on record’ and ‘global warming’ (as it was called then). Journalists have since quit the phrase ‘global warming’, replacing it with ‘climate change’ for precisely that reason, except too many people still struggle with the concept that an anthropogenically warmed planet does not mean ‘tropical weather, everywhere’. So that remains relatable, as does Marcia’s self-chastisement regarding her doomerist tendencies.

Marcia’s husband, Eric, is also a relatable, modern guy, who makes many (pretty much useless) modifications to his own lifestyle without deep thought regarding what would actually make a difference (quitting meat). Marcia can see the ironies in his choices: Eric doesn’t approve of fur clothing (because of the animal cruelty, we deduce) but Marcia points out at least it’s biodegradable. (I’m thinking, if he’s going to eat meat, isn’t it more ethical to use all of the animal?) Those of us who care are still embroiled in exactly this kind of unwinnable discussion. In many households, partners don’t agree on exactly what should be done to help The Cause. (Frequently, the divide is generational. Gen X at least enjoyed our childhoods thinking that if we put our wrappers in the bin, we could manage the world. Gen Z have never lived without climate anxiety.)

This dynamic between Eric and Marcia feels all too real, because the responsibility for the impending climate crisis is still being heaped upon individuals, and individual households, when in fact it’s just a few massive corporations doing almost all of the damage, so change needs to be made at the level of government policy.

Did anyone understand this in the late 1980s? Well, it wasn’t making the news.

THE STATUS OF WOMEN

When I read the autobiography of a local woman journalist who I admire, she portrayed a journalistic world of the 1980s which is far more hostile to women than it is today. This week, Australian headlines are remembering Julia Gillard’s misogyny speech. Gillard has said she can’t imagine the same misogynistic acts happening today without wide protest, so things have changed (at least here, in Australia) perceptibly in just a decade.

Margaret Atwood’s description of Marcia’s work and home life makes for a frustrating read, yet at the same time, Atwood was pretty subtle about it — offering a portrait without the commentary. The portrait itself is disturbing. No commentary needed:

- Marcia is contracted to write a column about women’s issues, because she is a woman. Yet Atwood doesn’t say that in the text at all. The newspaper is aimed at ‘businessmen’. We need to make that connection for ourselves. The 1980s were just beginning to open up a crack for female businessmen, and this column would have been for them. A nod. An attempt at performative inclusion. The writer of the “Lifestyle” column (code for Women’s Column) doesn’t get her own desk.

- But the man in charge has his own ideas about what ‘women’s issues’ are, and it’s nothing dark. If Marcia covers anything that’s not specifically about women, she’s not told directly that ‘women shouldn’t be writing about men’s issues’; she’s told she’s being “hysterical”. (If you’re not offended by that word, please do look up the etymology.)

- For all this, Marcia is made to feel fortunate to have this gig, because if she didn’t have this, she’d be singing the praises of some male politician by writing his autobiography for him. Compared to that blatantly lackey job, this one’s a breeze.

- Although Marcia herself writes for a newspaper (or perhaps because of it) she is unable to distance herself from the overwhelmingly toxic messaging directed at women in the 1980s. It’s difficult to comprehend now (when it’s bad in a different way) just how many dieting tips and ‘health advice’ was directed at women. Women’s bodies were white, tanned and rake thin. The media continues to struggle with diversity, but the 1980s were so much worse. The health messages directed at women in some cases led to health anxiety. Marcia worries about her health in a way that Eric doesn’t. The media trains men to worry about the Big News, without continual gaze and fretting about male bodies. (This gendered difference has its ups and downsides: men are less likely to visit a doctor. Married men live longer; presumably because their wives are looking out for them on their behalf.)

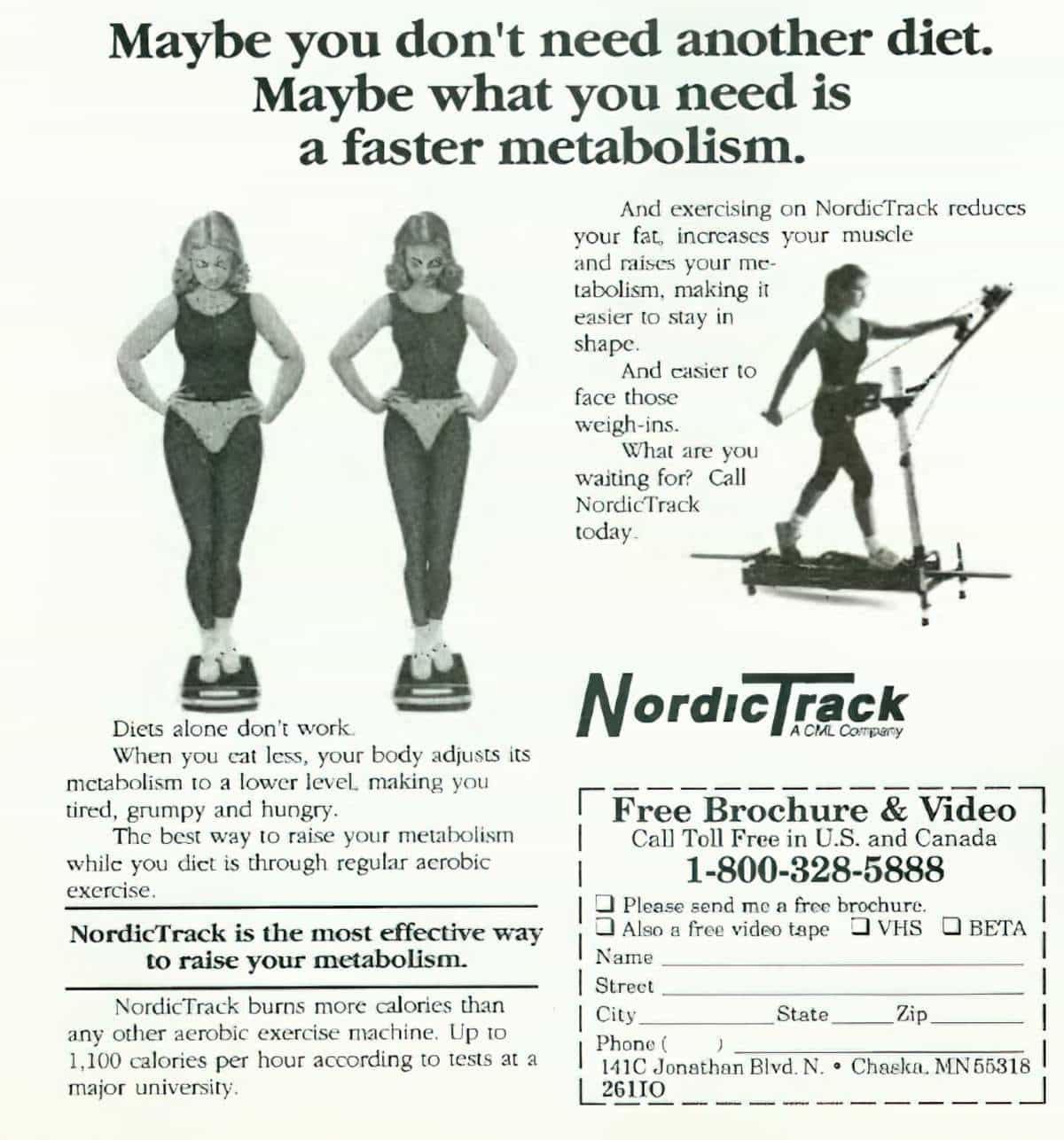

As one example, a flip through this very edition of The New Yorker Magazine leads inexorably, inevitably, to the very diet culture affecting Marcia in Margaret Atwood’s short story.

The woman’s ‘before’ body looks like today’s ideal body. And remember, this was The New Yorker. Publications aimed solely at women were so much worse. Here, sellers of a walking machine push educated, feminist women away from restrictive anorexia towards anorexia athletica instead.

In various ways, Marcia tries to stop time. She regrets not saving more items from the past, to remember her children when they were young.

For women, the desire to halt time has its outworkings in the body. When Marcia laments her widening backside, we can be sure she’s referring only to the natural width that comes to femme bodies in middle-age. For Marcia, ‘casting a shadow’ is unwomanly. Who doesn’t cast a shadow? (Invisible people, and the dead.)

The passage about Marcia’s day-of-the-week underpants from girlhood shows how 1980s expectations for women to be presentable at all times had morphed a little. In hindsight, Marcia is able to see how ridiculous it was, that you’d be on a hospital bed after suffering a light-threatening accident, and staff would be checking your underpants, to see if you’re a legitimate and proper version of womanhood before bothering to fix you up. The irony is, of course, that Marcia can see the ridiculous expectations in hindsight, but isn’t yet able to see the ways in which different, 1980s expectations affect her now.

“HACK WEDNESDAY” AND OLD AGE

Speaking of middle age, Atwood expert Carol Beran reads “Hack Wednesday” as a story about the nascent beginnings of old age, and compares it to another Atwood short story, “Happy Endings”. (For more on Beran’s concept of the ‘creative non-victim’, I refer you to the entire paper, which covers all of the short stories in Atwood’s Wilderness Tips collection.)

For some readers, the elegiac tone of “Hack Wednesday,” sweetly sentimental about aging to begin with, becomes cloying by the end of the story. Yet, as in the story of John and Mary that Atwood satirizes in “Happy Endings” in Murder in the Dark, the “only authentic ending” is “John and Mary die. John and Mary die. John and Mary die”; fact, not nostalgia. Alzheimer’s disease may one day obliterate bittersweet memories and make Marcia a real stranger to herself. Her partner’s futile crusades may devolve into more meaningless symptoms of old age. Amid the sentimentality, we can recall Dylan Thomas’s plea: “Do not go gentle into that good night. / Rage, rage against the dying of the light”. From there we can move beyond rage into being creative non-victims, people who can accept their own experience “for what it is, rather than having to distort it to make it correspond with others’ versions of it” (Atwood, Survival, 39), which may be precisely what Marcia does.

Strangers Within the Gates: Margaret Atwood’s Wilderness Tips by Carol L. Beran

This would explain Marcia’s mulling over babies, which bookends the story. A reader with fixed ideas about women’s role (birth and childrearing) might mistake this for cluckiness, or for a woman’s loss of feminine identity as she becomes an empty-nester and is no longer able to give birth herself. But I think a more knowing take is not a gendered reading at all: Marcia thinks of babies because lack of babies in her life means she is no longer young, which simply means she’s closer to the grave.

Since age affects us all, this story of babies could equally have been told of a man. (Perhaps we need more stories about men who get maudlin about babies.) Margaret Atwood pushes us away from the soppy reading by telling us that, although Marcia likes babies, she doesn’t actually want one; ‘Now I will have to take care of it. This wakes her up with a jolt’.