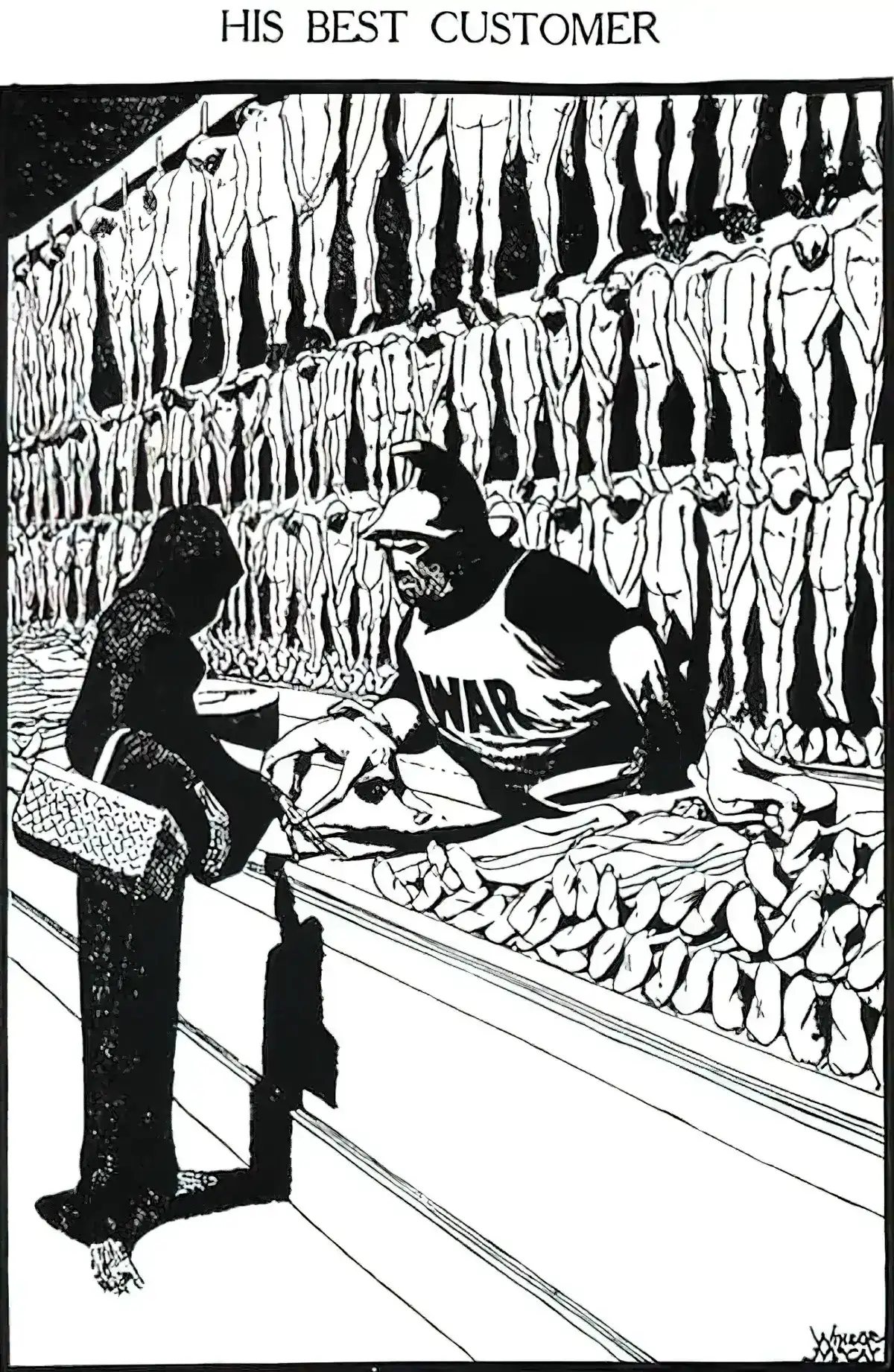

For Death must be somewhere in a society; if it is no longer (or less intensely) in religion, it must be elsewhere; perhaps in this image which produces Death while trying to preserve life. Contemporary with the withdrawal of rites, Photography may correspond to the intrusion, in our modern society, of an asymbolic Death, outside of religion, outside of ritual, a kind of abrupt dive into literal Death.

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography

LOVE AS A MINI DEATH

To love! To surrender absolutely, to prostrate oneself before the divine image, to die a thousand imaginary deaths, to annihilate every trace of self, to find the whole universe embodied and enshrined in the living image of another! Adolescent, we say. Rot! This is the germ of the future life, the seed which we hide away, which we bury deep within us, which we smother and stifle and do our utmost to destroy as we advance from one experience to another and flutter and flounder and lose our way.

Henry Miller, The Rosy Crucifixion

SLEEP AS A MINI DEATH

Adventures In Sleep from All In The Mind podcast

Scientists still don’t know why we need to sleep. Contrast that lack of full understanding with nutrition science, in which we fully understand why animals need to eat, how nutrition enters the blood stream, how it is metabolised and so on. Sleep remains far more mysterious.

But we do know more and more about sleep, partly thanks to people with disordered sleeping. Some people sleepwalk, drive cars and cook meals in their sleep. Because of this, we have come to understand that parts of the brain can be asleep while other parts remain fully awake. This also applies to the sleep deprived, who won’t notice that part of their brain is asleep while they are technically still ‘awake’, but they will know they’re not on top of their game.

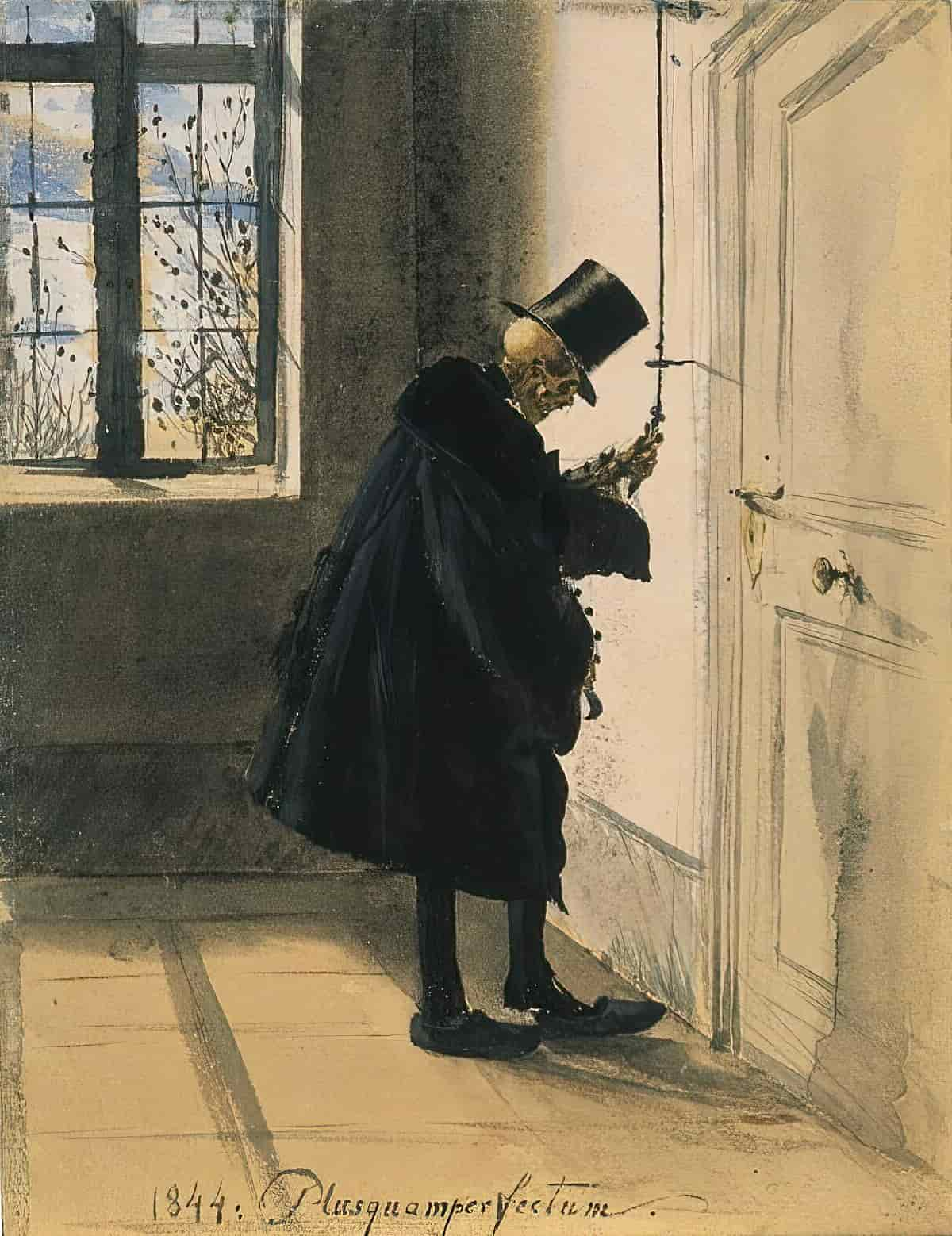

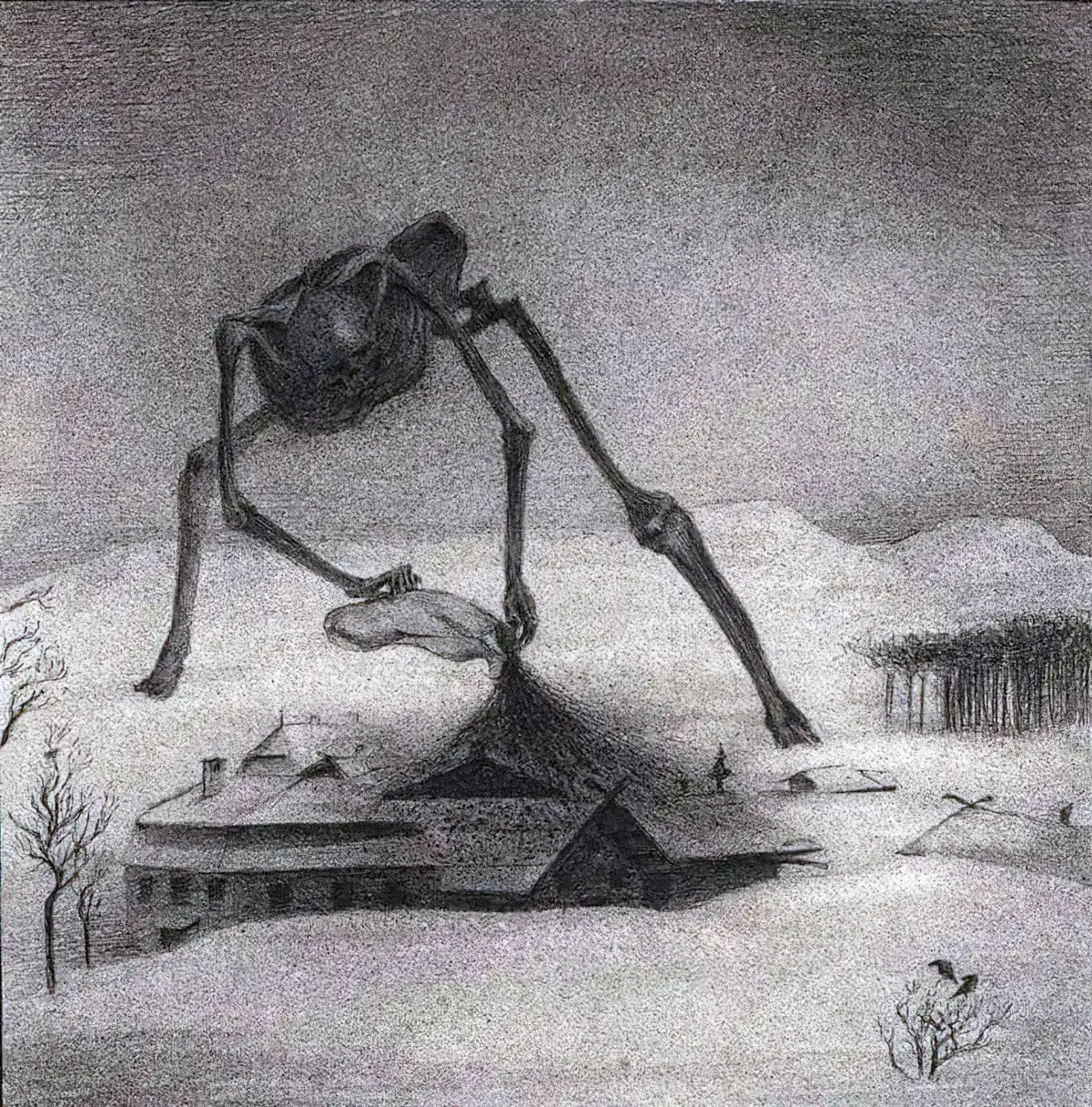

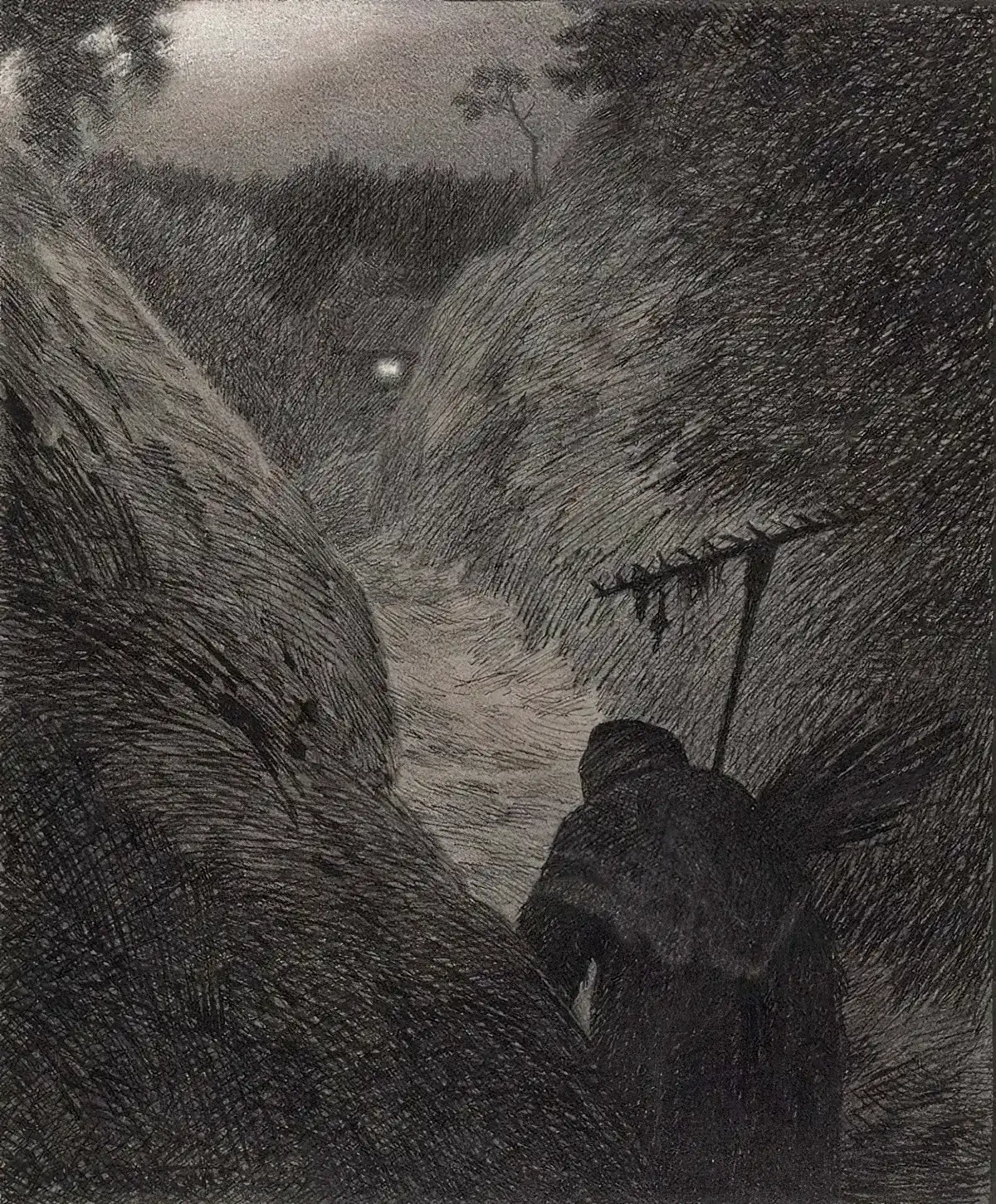

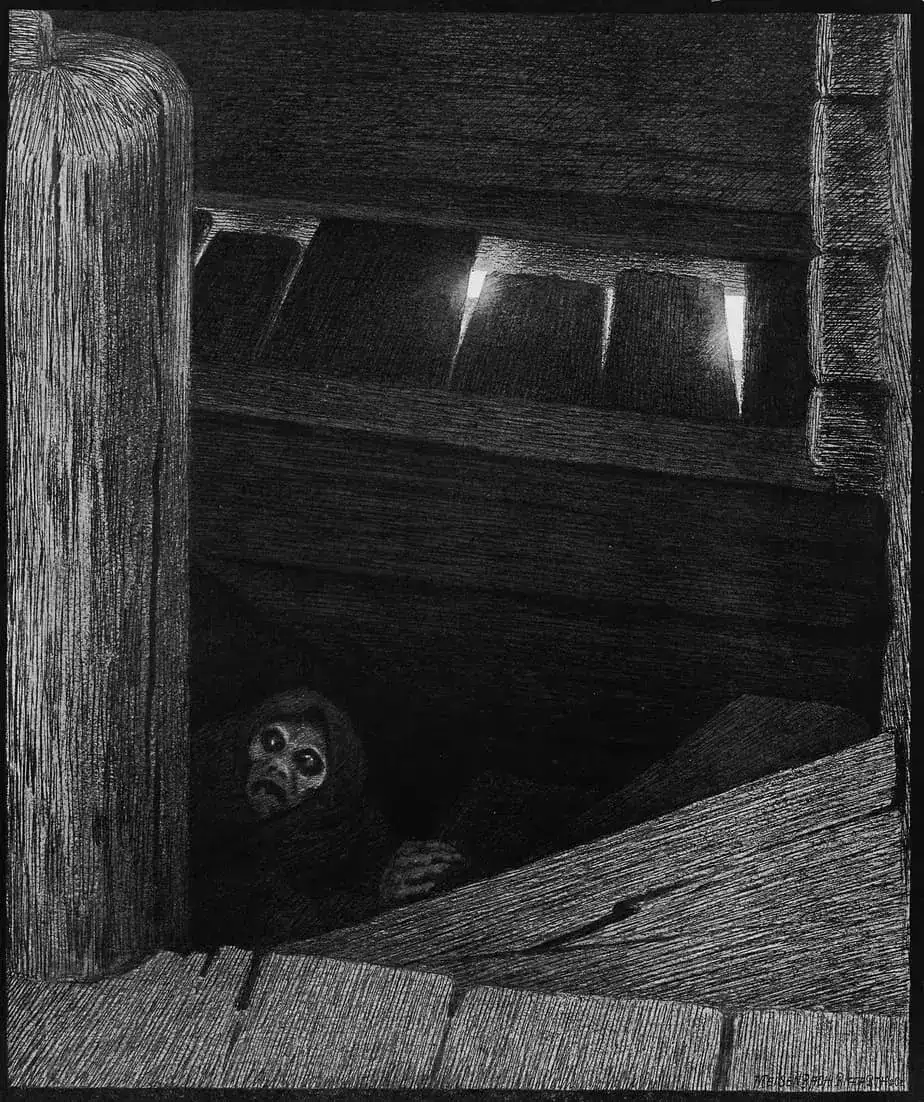

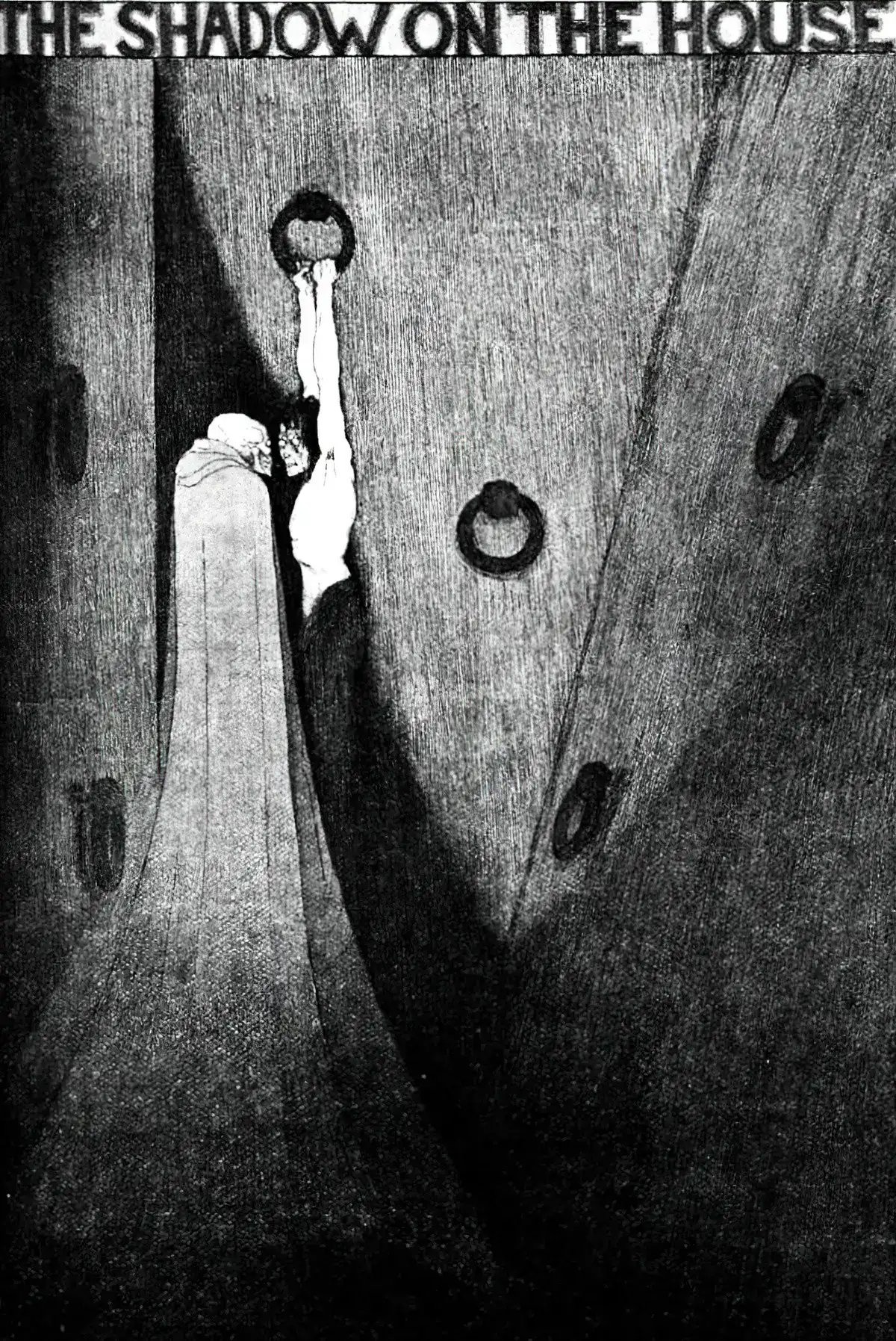

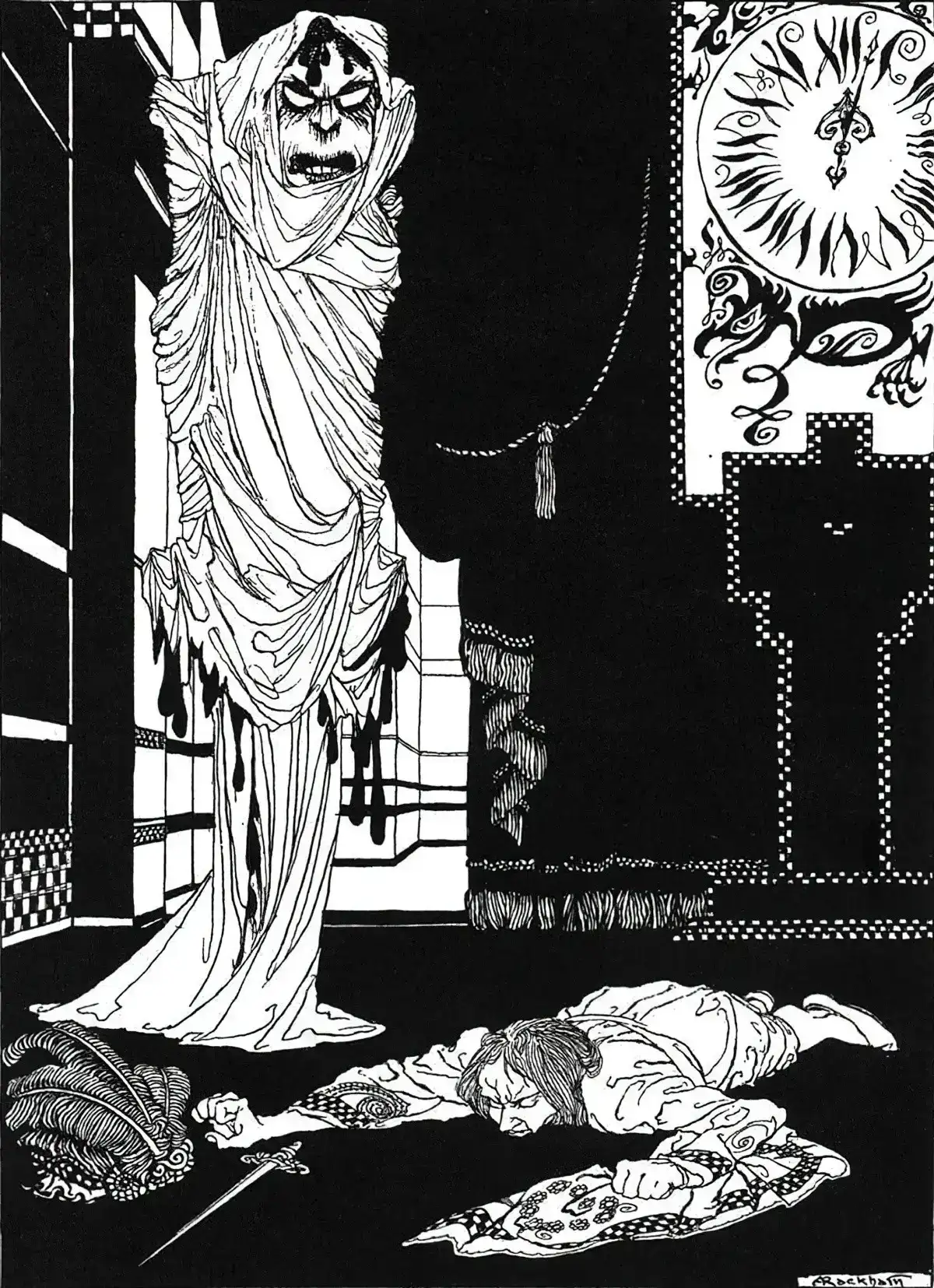

The inverse of sleepwalking is sleep paralysis — a terrifying experience. This is where your brain is awake, but your body remains asleep. To make matters worse, this experience often goes hand in hand with the nightmarish visions in which dark figures seem to be creeping into the room.

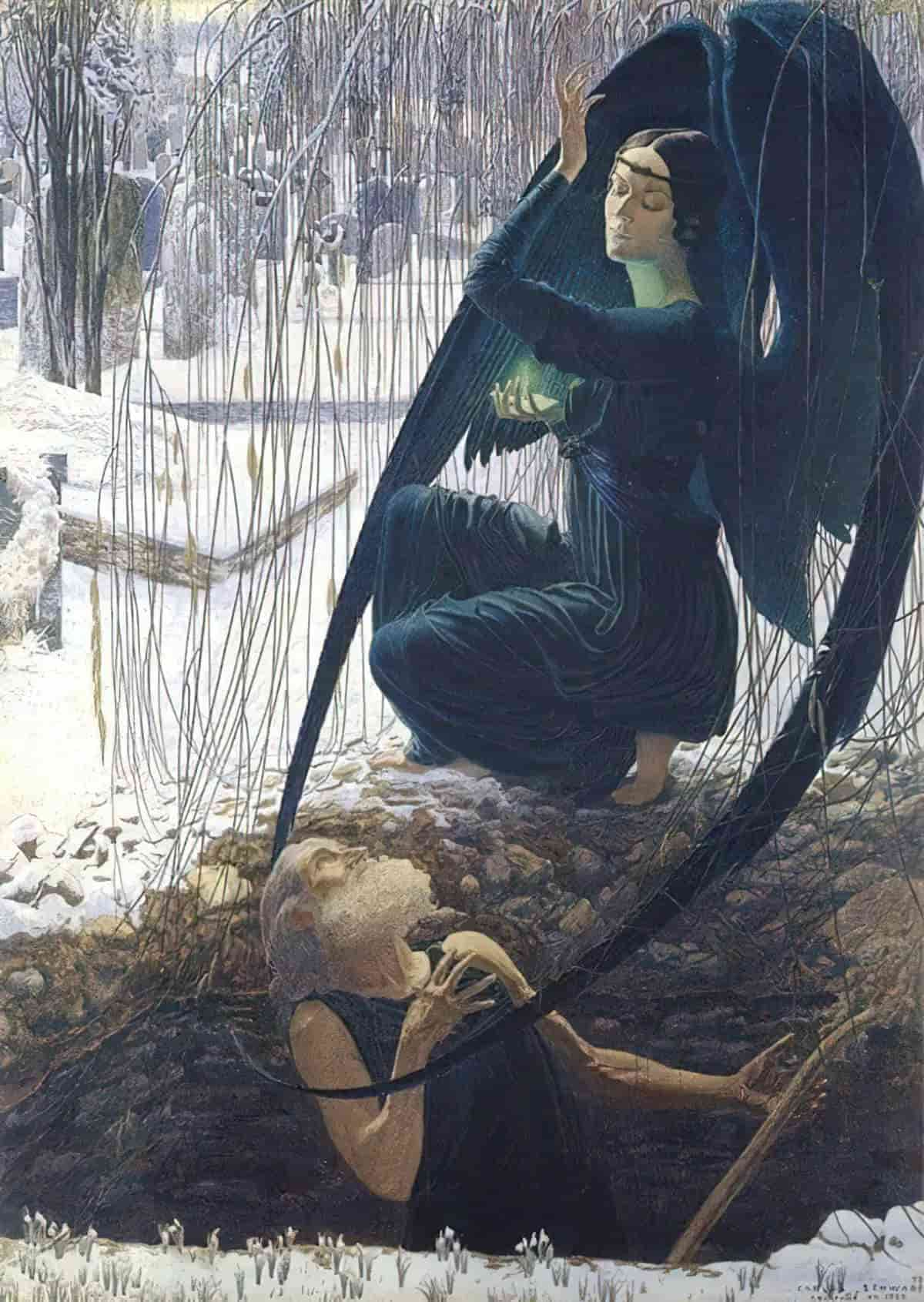

In many ways, symbolically and experientially, sleep can feel like a form of death. Also, a common time to die is in the early hours, when metabolism plummets. People near death are at their most vulnerable at about four in the morning.

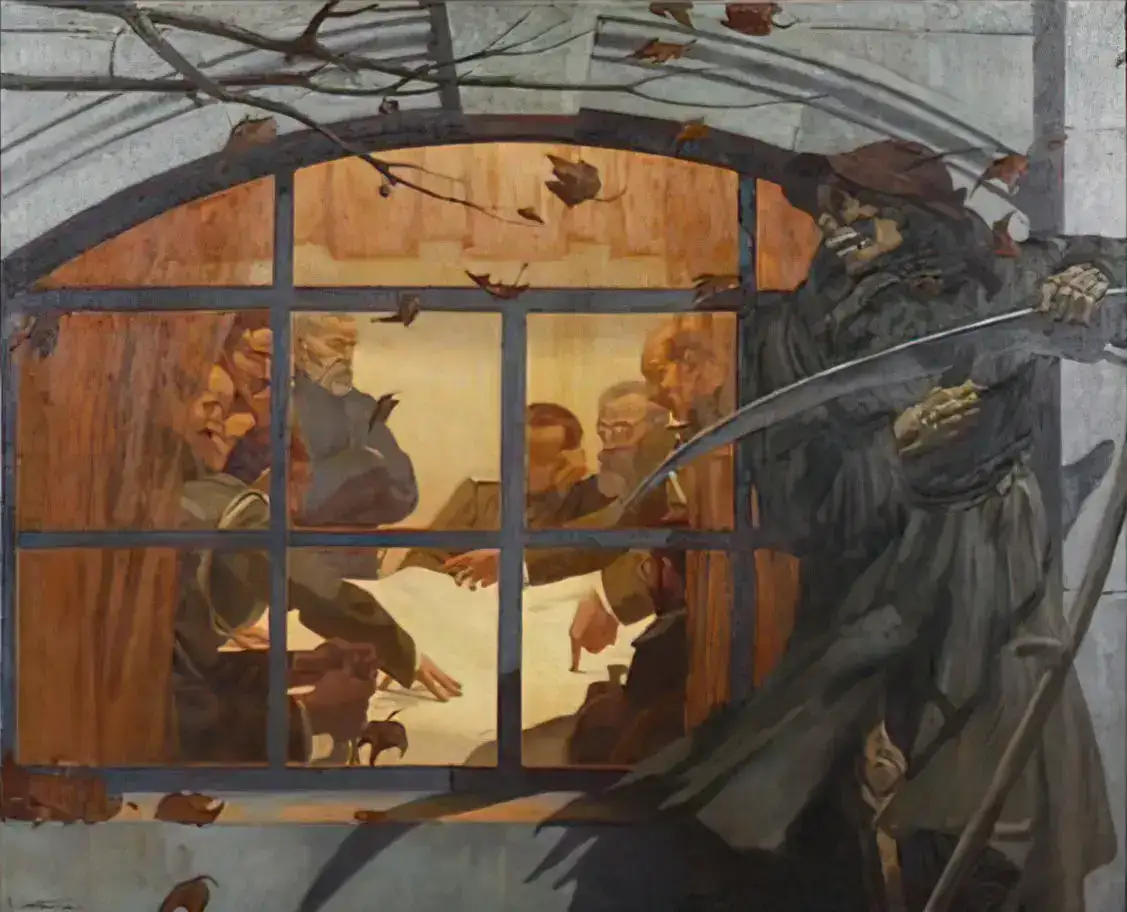

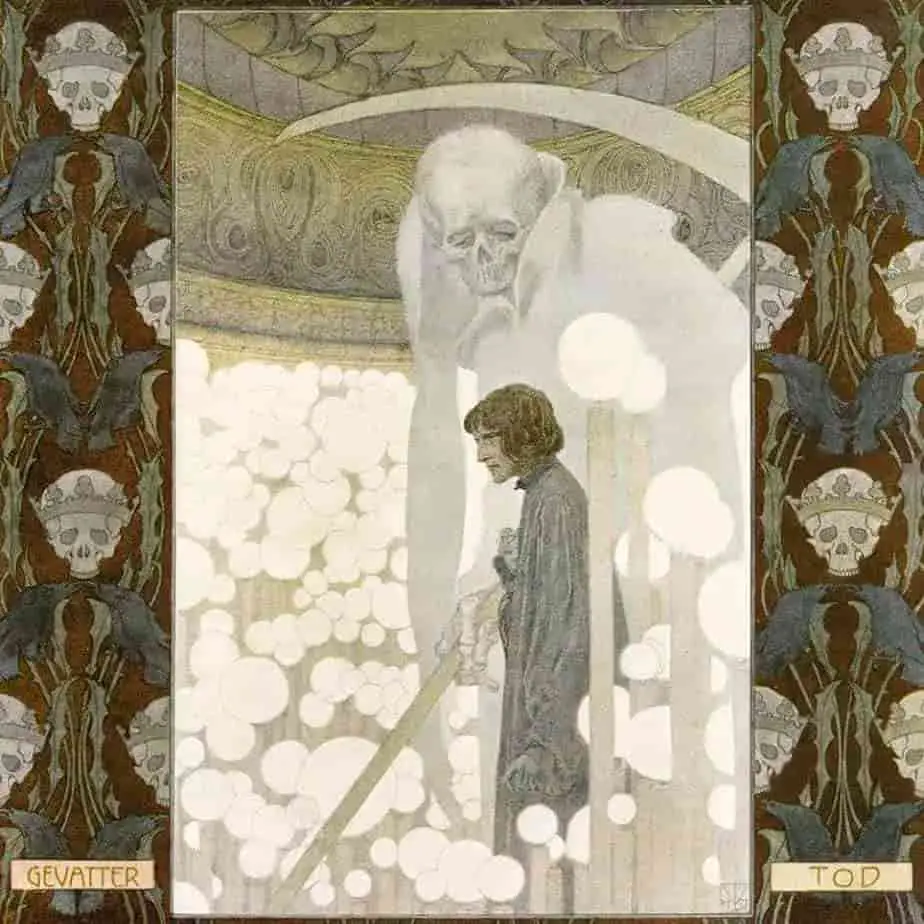

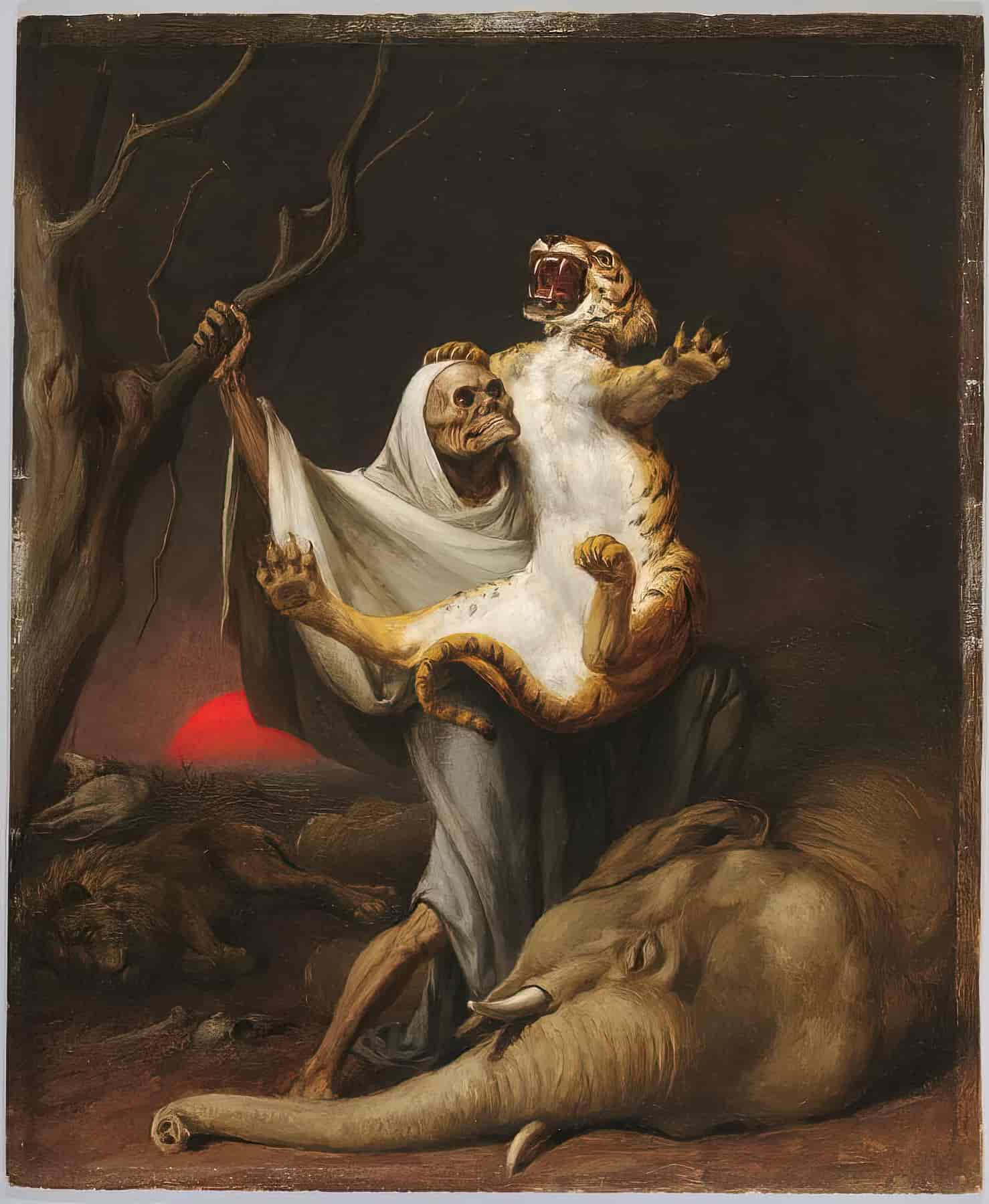

Visions of death near the bed are therefore commonly found in stories and art.

La Thangue was well-known for his realist rustic scenes. Here, uncharacteristically, he introduces a symbolic dimension to his work. A mother discovers that her young daughter has died, presumably after an illness. At the same moment, a man arrives at the gate carrying a scythe, the traditional symbol of death, the ‘grim reaper’.This rather melodramatic treatment can be compared with the more grimly realistic picture of child death Hushed, by Frank Holl, also shown in this room.

Gallery label at The Tate, July 2007

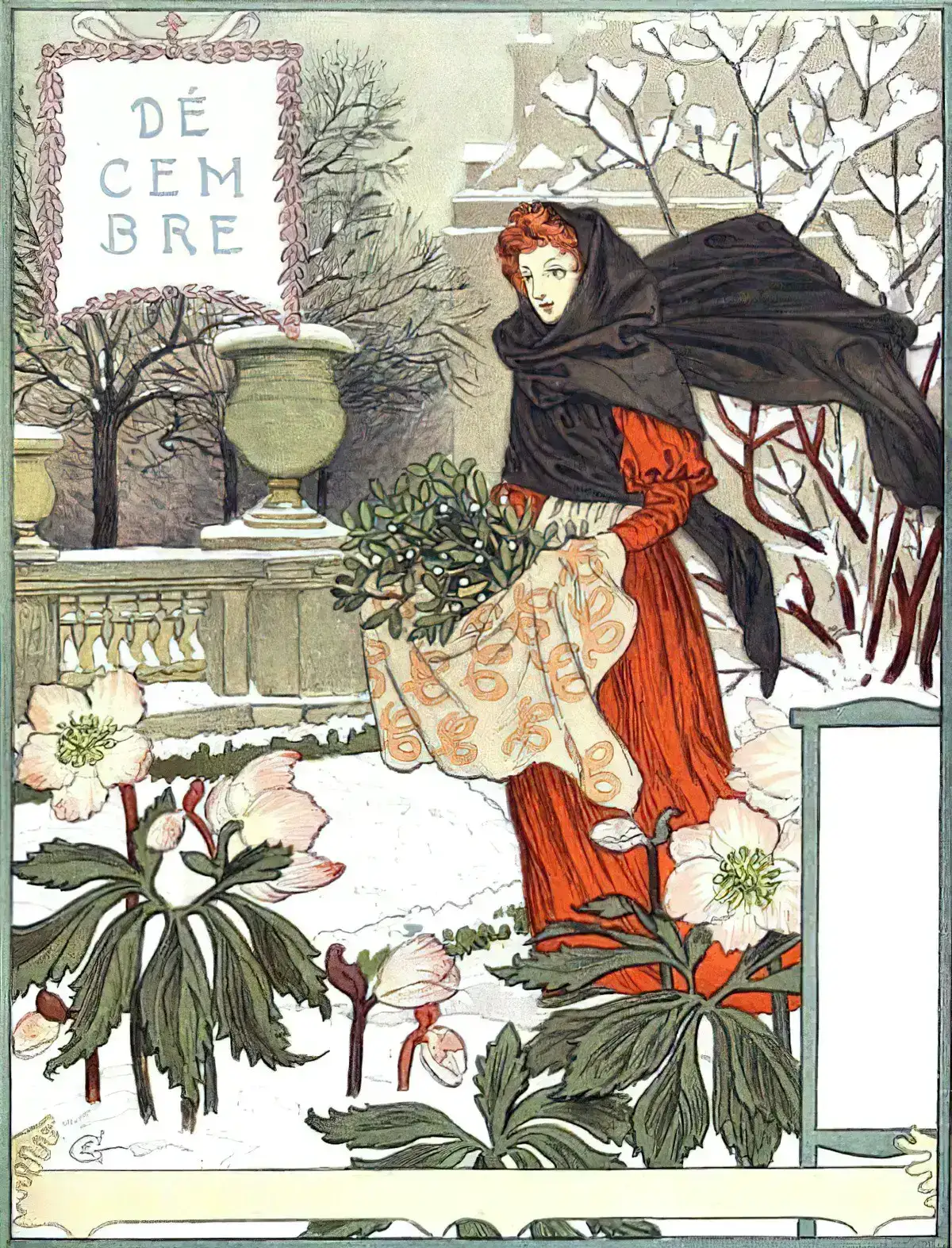

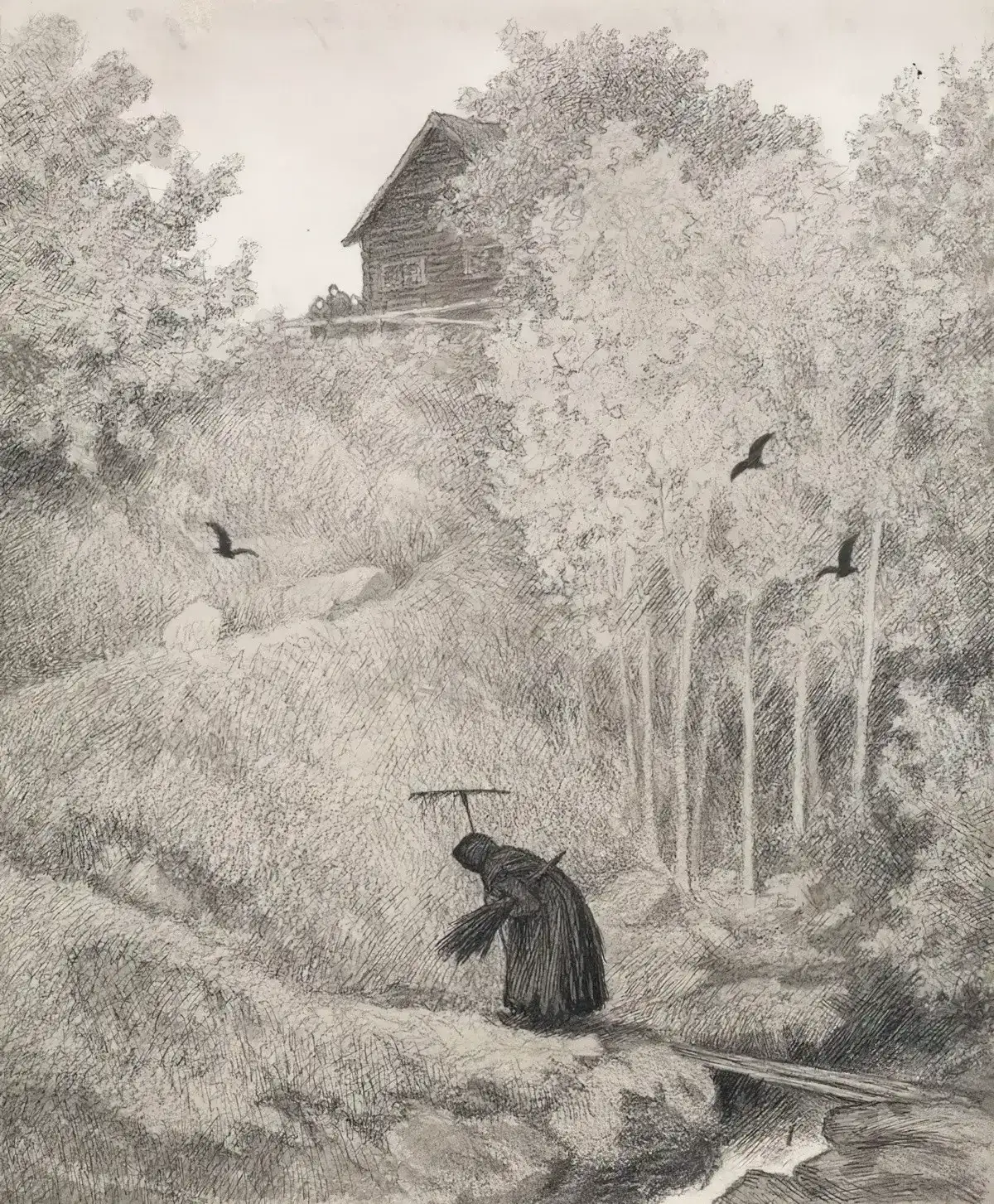

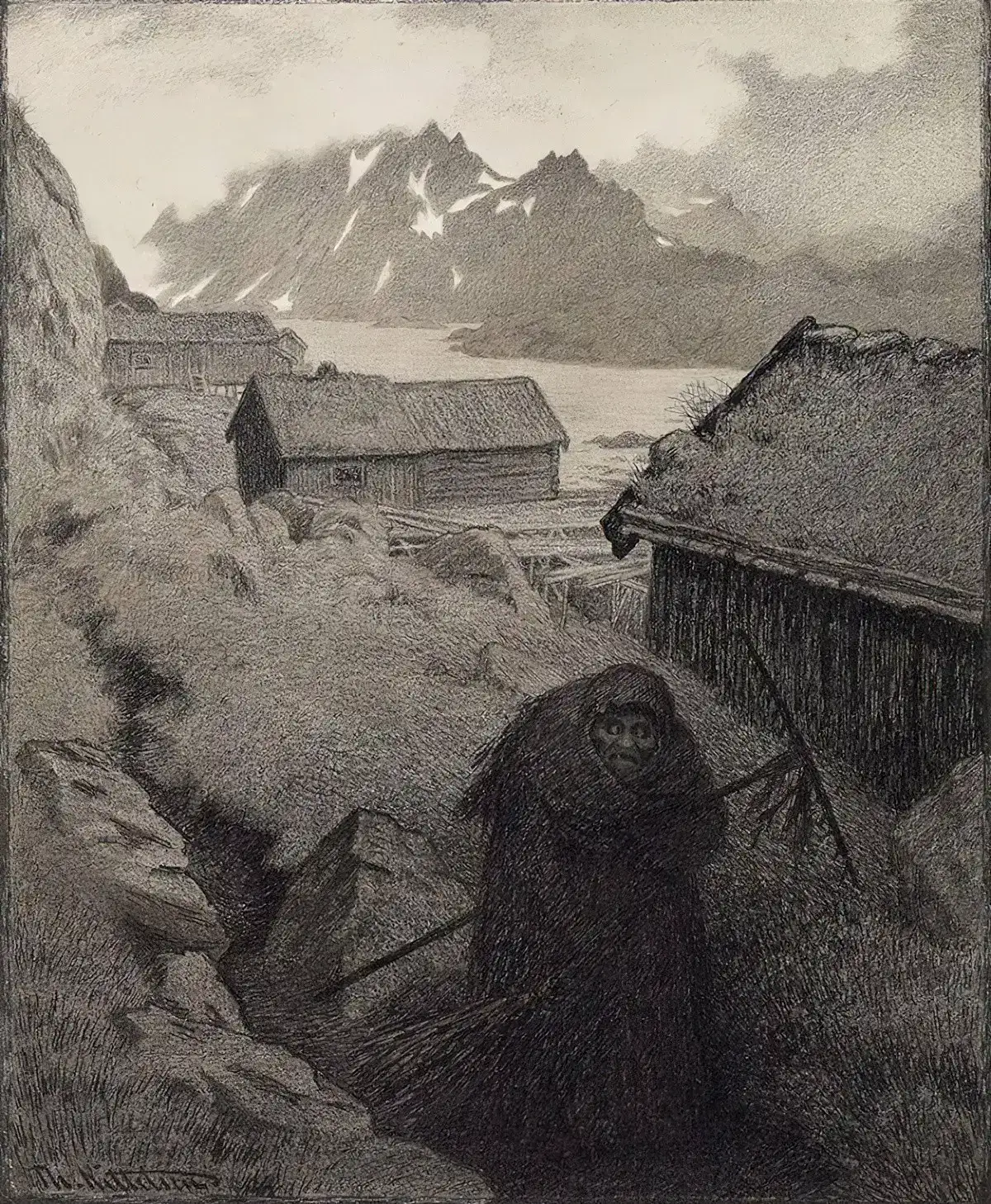

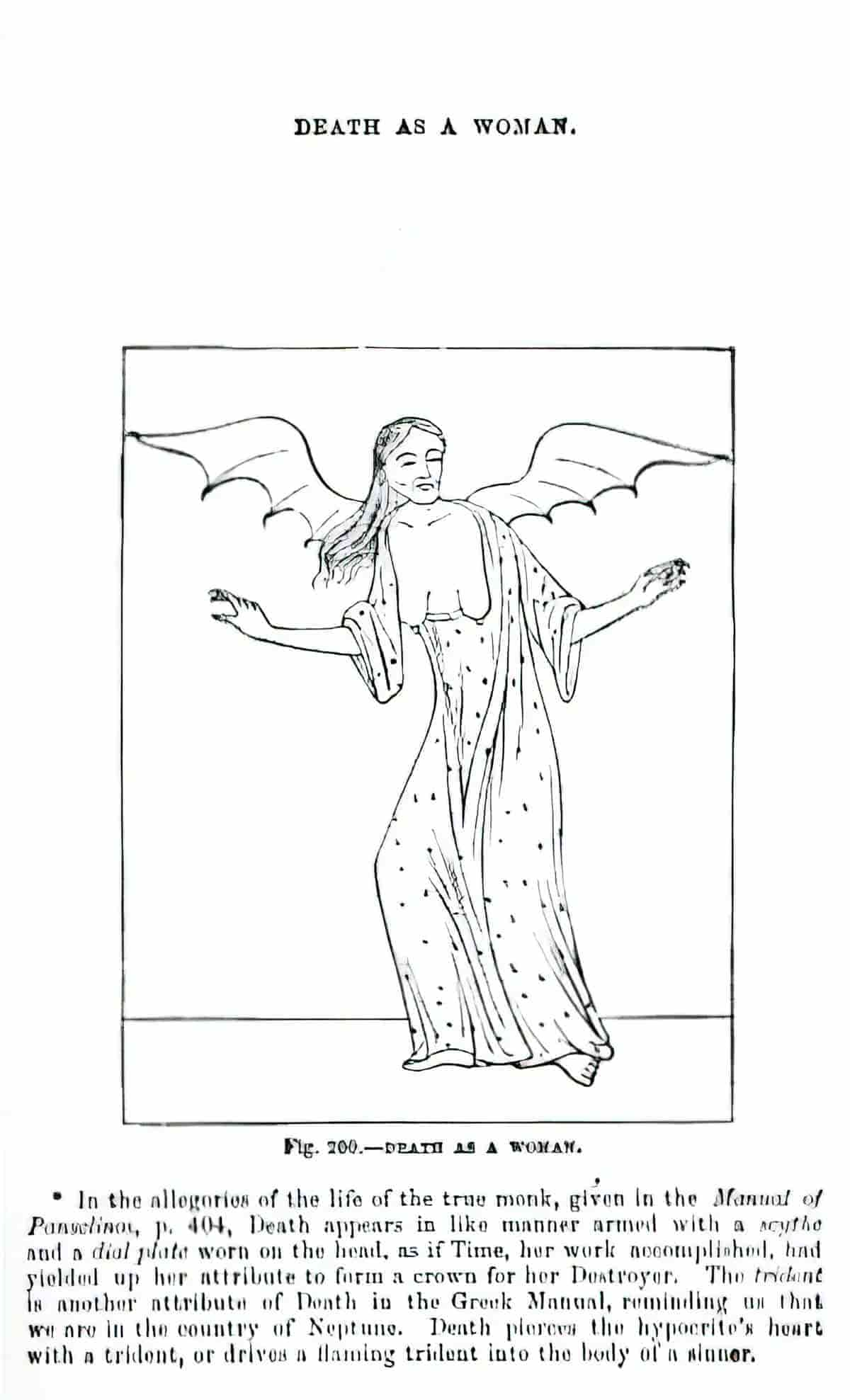

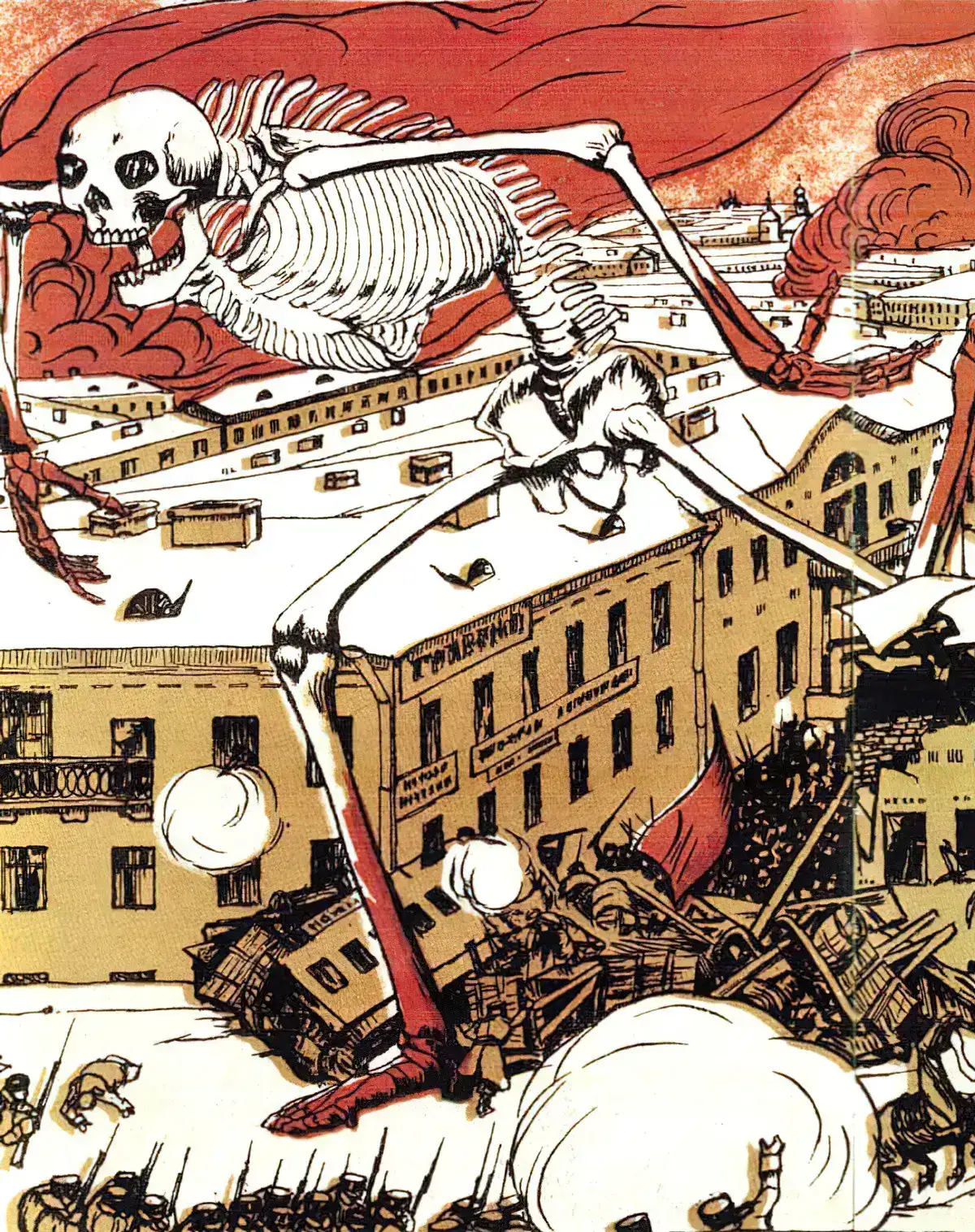

The modern Grim Reaper is more often a man, but the Black Death was seen as an old woman walking the land, with a broom and a rake. Where she raked, some survived. Where she used the broom, everybody died. Old women are more common than old men, which probably accounts for much of the opprobrium directed at old women.

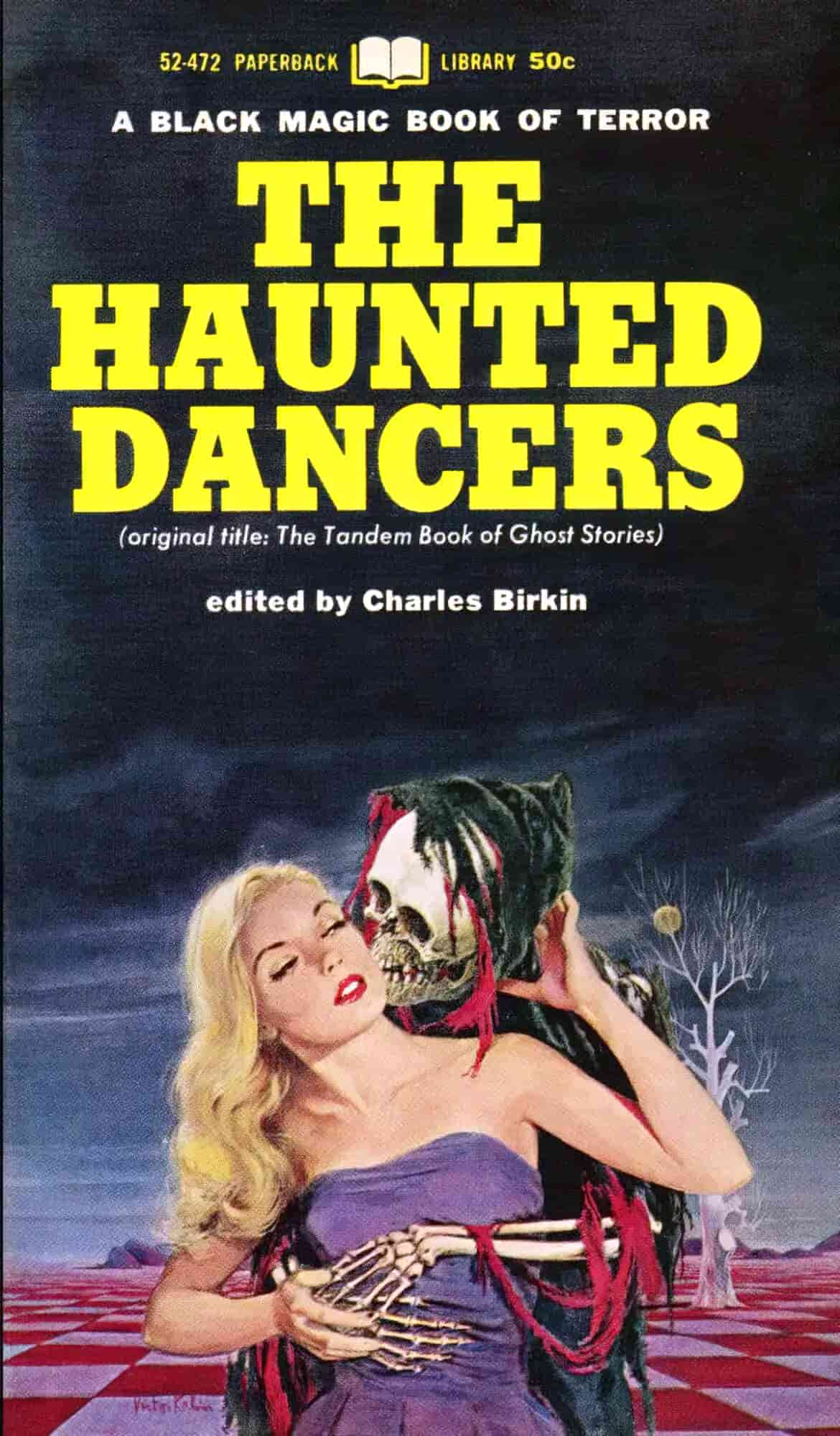

Whenever folklore contains a scary old woman, later artists will always, always subvert the idea of witch-like power by depicting her as an alluring young woman.

Skeletons As Death

Not surprising, of course, that skeletons are associated with death.

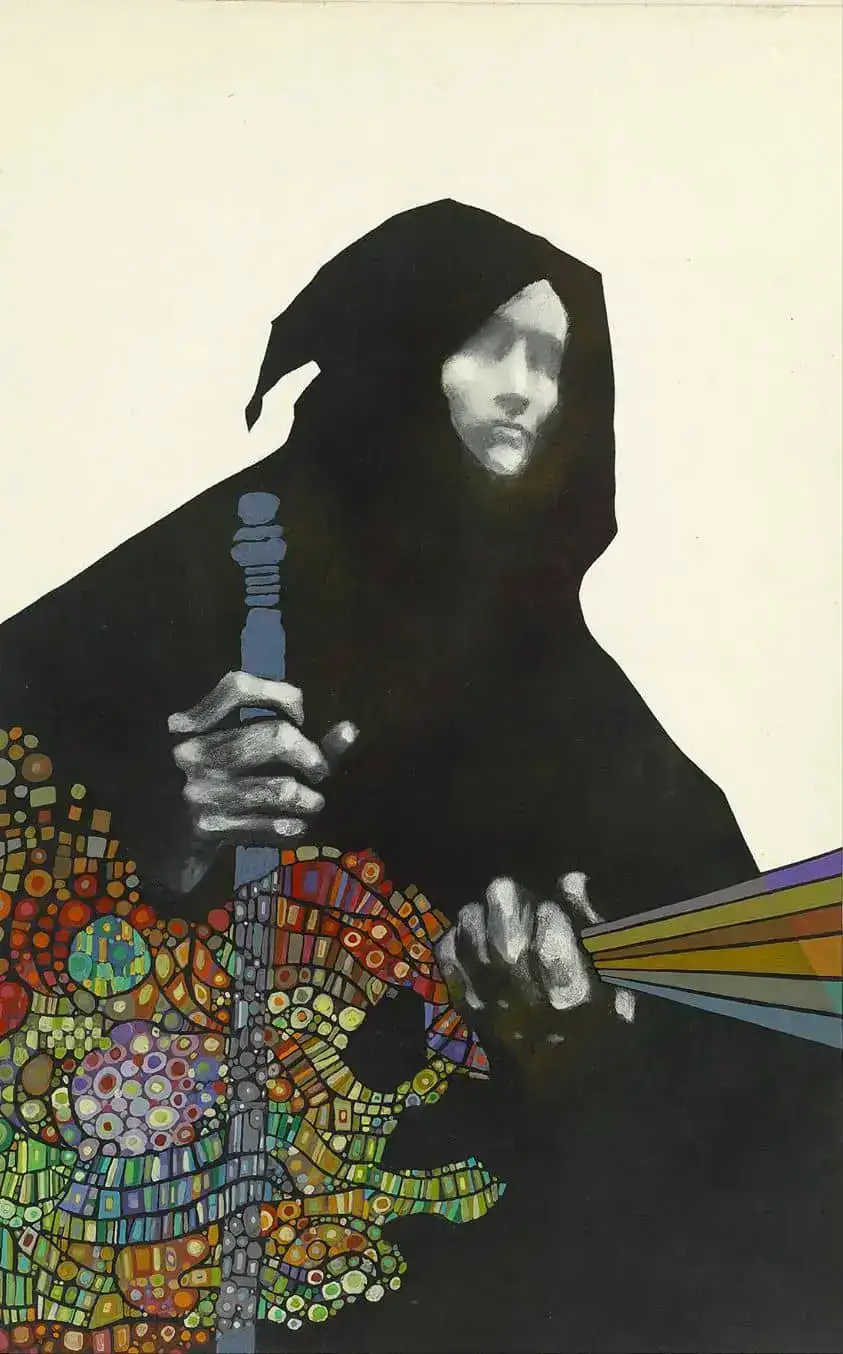

The Symbolic Inverse of the Grim Reaper

In contemporary lore, death more often looks like a man. The painting below is a useful portrayal of symbolic opposites. Death is a malnourished male figure holding a scythe, whereas the inverse of death is a pregnant woman decorated in flowers and pears. The painter Ivar Arosenius did this painting three years before his own death. Perhaps he was contemplating his own demise.

DEATH AND THE ANCIENT GREEKS

You don’t see much of Hades, God of the Underworld, in Greek art because the Ancient Greeks were so scared of him! They didn’t even want to say his name, so he goes by many other names.

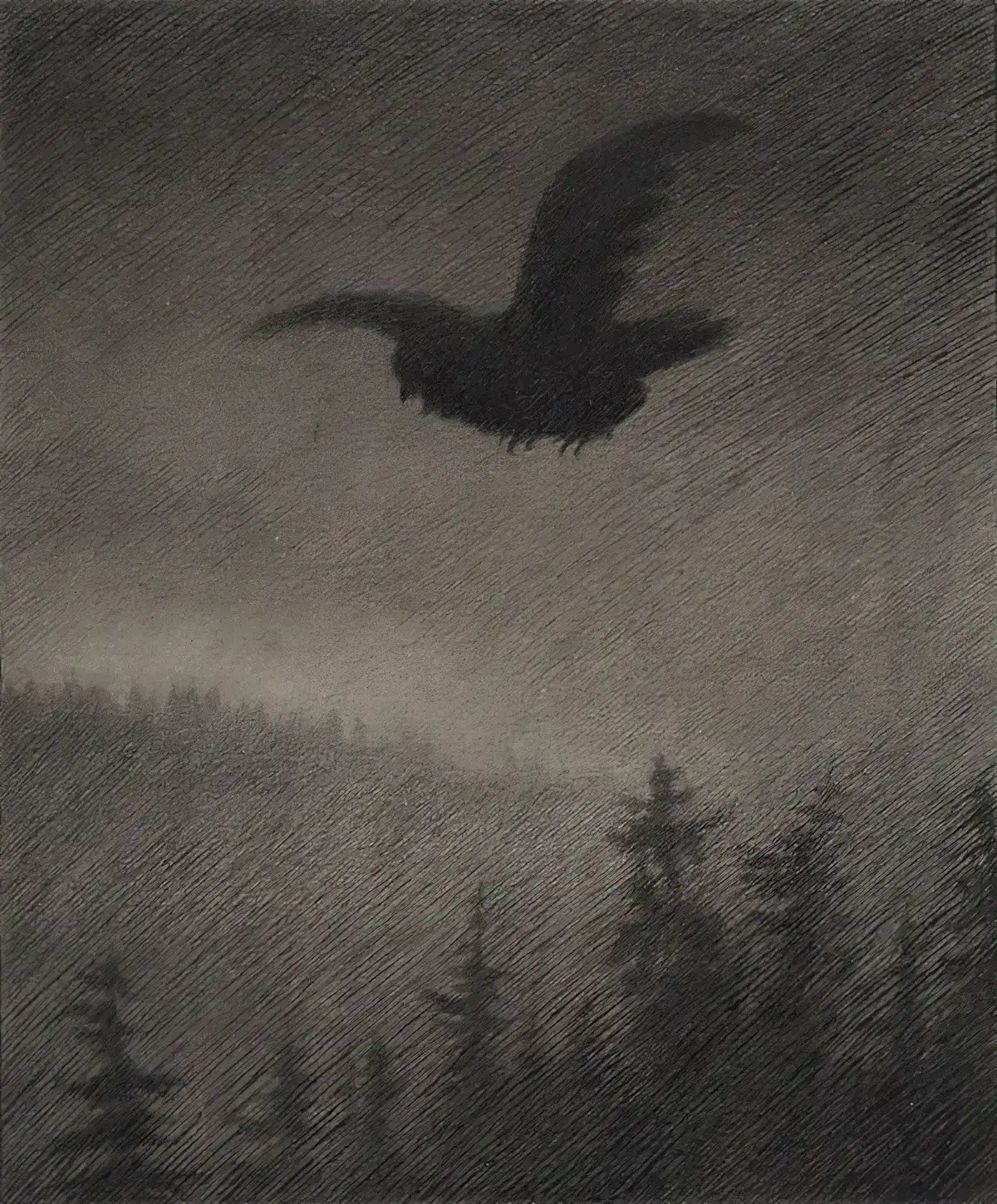

Hades ruled the Underworld and was therefore most often associated with death and feared by men, but he was not Death itself — it is Thanatos, son of Nyx and Erebus, who is the actual personification of death, although Euripides’ play “Alkestis” states fairly clearly that Thanatos and Hades were one and the same deity, and gives an interesting description of Hades as being dark-cloaked and winged; moreover, Hades was also referred to as Hesperos Theos (“god of death & darkness”).

Wikipedia

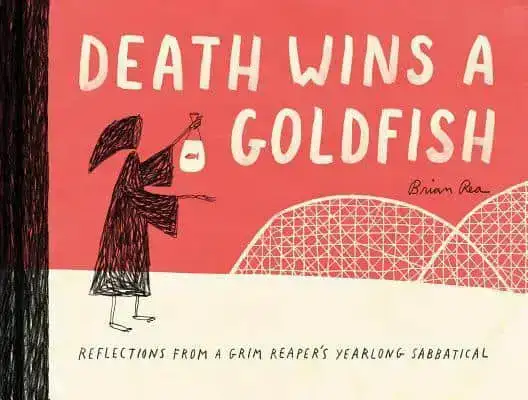

Even Death cares about his work-life balance…

Death never takes a day off. Until he gets a letter from the HR department insisting he use up his accrued vacation time, that is. In this humorous and heartfelt book from beloved illustrator Brian Rea, readers take a peek at Death’s journal entries as he documents his mandatory sabbatical in the world of the living. From sky diving to online dating, Death is determined to try it all! Death Wins a Goldfish is an important reminder to the overstressed, overworked, and overwhelmed that everyone—even Death—deserves a break once in a while.

STORIES WHICH PERSONIFY DEATH

- “Who’s-dead McCarthy” by Kevin Barry

- “Save The Reaper” by Alice Munro and the story she used as palimpsest, “A Good Man Is Hard To Find“, by Flannery O’Conner.

Header illustration: René Bull (1872-1942) 1913 illustration for Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám