Notes below are from David Beagley, La Trobe University, Genres In Children’s Literature.

Lynd Ward’s Eerie, Early Graphic Novel, “Gods’ Man” is thought to be the precursor to the modern novel.

Superman and Astroboy are well-known comics. Astroboy is a mix between man and machine which has given us Lego bionicles and Transformers, and which reaches its peak in Lego versions of Starwars, particularly in the games.

There is a perception that just because it’s a cartoon or a comic, children are the audience.

Ever since Disney’s version of Snow White in the 1940s this has been the case. There are very few animated movies for adults, yet so many of them carry adult themes.

Depression, destruction — all this comes through on the latest Batman movies

Art Spiegelman Maus (written in German) — father’s experience during Holocaust, WW2. This was incredibly influential. It came out in the late 80s. Spiegelman was working as a cartoon artist, so used this medium to tell this story. This was the first of its kind.

Picturebooks provide more reluctant readers with a more acceptable way to get their literature. ‘Spoonful of sugar’ helps the medicine go down. The downside of this is the presumption that literature is difficult and therefore not an enjoyable experience.

Just about every Shakespearian play has a graphic novel version — mostly in multiple versions, usually paying homage to the Japanese manga style. Others are realistic picture versions.

A lot of them make use of pop culture, to things outside the actual story. All of these things are there in picturebooks for older readers as well as in graphic novels.

Woolves in the Sitee, Way Home, Rose Blanche — graphic novels use the same things as these picturebooks. The visual vocabulary is shared — how pictures and symbols tell their stories (explained previously in The Drover’s Boy, with the sticky tape put as a cross over the lock of hair).

When stories go on for a long time in a series (e.g. Tomorrow When The War Began by John Marsden) you may start with a realistic story, but it ends up being a caricature of real life — more cartoon-like.

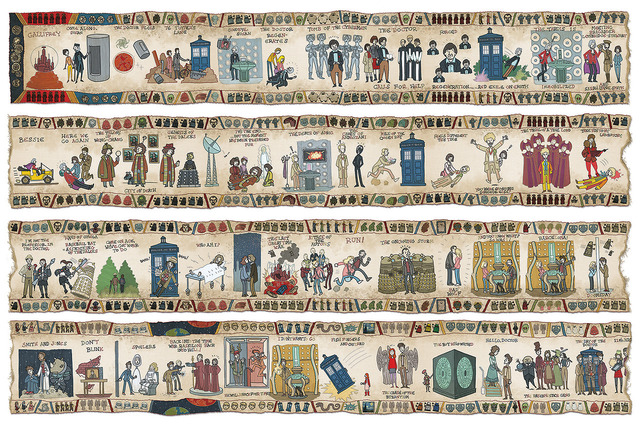

Generally, as soon as a character solves a crisis, someone else turns up to make it worse and worse and worse. Dr Who is probably the best British version of this kind of character, who is a live version of a cartoon character.

Take Batman. One concern about these types of movies, in which the hero is, in actions, not much different from the villain, is that a young audience won’t necessarily get that. There’s no clear morality — the message is that it’s all right to go out on a bike and blast anyone that’s in your way. The message is that ‘Your identity as a good guy makes you right, not your actions.’ [Side note: for more on this issue read Deconstructing The Hero, written by Marjery Hourihan.]

This is Alfred and Bruce talking about a fairly complex idea:

The ‘Dead White Male’ approach to literature — all great lit is hard, and written by this demographic. But there is probably more analysis going on of Harry Potter than anything else at the moment.

The graphic novels of classic works such as those by Shakespeare are abridged versions. How much subtlety is lost? Do they bring audiences to the classics, or are they diluting the classic away from whatever it was that made it a classic? In Shakespeare’s case it wasn’t the great events but the talking in between which makes it a classic.

Nicki Greenberg presents a certain version of Hamlet in her graphic novel.

When Tin Tin was reprinted, we realised how outdated it had become with the golliwog, little black sambo stereotype. This caused huge ructions when it was reprinted a few years ago.

Spiderman took one side in American politics.

Fashion can both reflect what is street fashion and often exaggerates it. There’s an exaggeration of the standard model type figure. It can also lead fashion. A lot of the Japanese fascination with the school girl does come from these cartoon representations as the epitome of sweetness and innocence. Then there’s cosplay, which is dressing up in the costumes of cartoon characters, which is now seen outside Japan.

Cosplay: The Fictional Mode of Existence

Cosplay, a portmanteau of “costume” and “play,” emerged from geeky Japanese subcultures to become a popular hobby, and even profession, around the world. Frenchy Lunning dives into the reasons why people cosplay through interviews, pictures, and her own firsthand experience of cosplay events in America and Japan. She distills the essence of cosplay to performance and the negotiation of identity, a pair of concepts that she interrogates in part by contrasting cosplay practices in America and Japan.

Cosplay: The Fictional Mode of Existence (U Minnesota Press, 2022) is livened with extensive photographs and fascinating tidbits about key figures in cosplay, such as Mari Kotani. Cosplayers are allowed to speak for themselves, describing what cosplay means to them and how they use it to negotiate their social roles and identities in fascinating detail. Lunning layers individuals’ testimony on a history of cosplay that highlights the changing settings, technologies, and communities supporting cosplay over the decades to leave readers debating what role cosplay will play in the construction of future identities.

New Books Network

Three distinct styles of graphic novels and comics around the world: (Beagley’s own names) 1. The Linear Narrative. The story is told as the continuous sequence of frames across the page as we go. 2. Action Packed Narrative, with a continuous series of big events and violence. 3. Manga-Meander. The soap operas — telephone book sized thing that run year after year without the story ever finishing. There are crosses between them. Dragonball-Z is both action packed and manga-meander. Most of the manga though are to do with personal relations, even though they might feature robots and monsters.

Gentleman Jim Raymond Briggs is about a man who wonders whether his job cleaning public toilets is as fulfilling as it ought to be. The emphasis is on the storyline, not so much the pictures. Asterix, Maus: the pictures are there to deliver the story. (When the Wind Blows, Fungus The Bogeyman, the same.) Marcia Williams does a lot of adaptations of classics, with emphasis on the storyline.

Then there are the action packed ones: out of space, SF e.g. Dan Dare Space Hero. The first was probably Flash Gordon, which became a movie very quickly as well. This is where we get a lot of cinema technique. There is a big crossover. Different size frames, explosions going across the page, big bold letters ‘pow’ ‘zam’.

Manga Meander: great scenery, nice clothing, not quite the pow zap explosive sort of story but there may be lots of action.

Anime is from ‘animation’. Manga is an aimless picture — doesn’t mean anything on its own, meant to be one of many. You could say Shaun Tan’s work fits the manga meander style.

Anime’s Identity: Performativity and Form Beyond Japan, UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA PRESS 2021

A formal approach to anime rethinks globalization and transnationality under neoliberalism Anime has become synonymous with Japanese culture, but its global reach raises a perplexing question–what happens when anime is produced outside of Japan? Who actually makes anime, and how can this help us rethink notions of cultural production?

In Anime’s Identity: Performativity and Form Beyond Japan (U Minnesota Press, 2021), Stevie Suan examines how anime’s recognizable media-form–no matter where it is produced–reflects the problematics of globalization. The result is an incisive look at not only anime but also the tensions of transnationality. Far from valorizing the individualistic “originality” so often touted in national creative industries, anime reveals an alternate type of creativity based in repetition and variation. In exploring this alternative creativity and its accompanying aesthetics, Suan examines anime from fresh angles, including considerations of how anime operates like a brand of media, the intricacies of anime production occurring across national borders, inquiries into the selfhood involved in anime’s character acting, and analyses of various anime works that present differing modes of transnationality. Anime’s Identity deftly merges theories from media studies and performance studies, introducing innovative formal concepts that connect anime to questions of dislocation on a global scale, creating a transformative new lens for analyzing popular media.

at New Books Network

The Soul of Anime: Collaborative Creativity and Japan’s Media Success Story

You may come for the Astro Boy or Afro Samurai, but you’ll stay for the innovative ways that Ian Condry‘s new book brings together analyses of transmedia practice, collaboration, and materialities of democracy. The Soul of Anime: Collaborative Creativity and Japan’s Media Success Story (Duke University Press, 2013) is based on ethnographic fieldwork in a range of spaces of anime production that include studios, toy factories, fan conventions, and online communities. What results is a fascinating exploration of how the social aspects of media generate successful anime tv programs and films, forms of labor, and ways of thinking about masculinity, love, and modern life. Condry argues that collaborative creativity has been central to producing the social energy necessary for the global success of Japanese anime. For Condry, it also helps explain a broader “globalization from below” whereby new forms of media emerge from local and grassroots efforts to appeal to and impact a diverse range of audiences. Through a series of case studies that observe contemporary and historical anime production practices from different angles, readers of The Soul of Anime are offered a window into the many forms of labor necessary to produce the many different media that collectively make up anime production, from the painstaking production of handmade storyboards to the conceiving of innovative characters and worlds that serve as platforms for the creation and circulation of anime stories. In addition to all of this, there are little boy samurais with wind-up keys in their heads, gods that speak only in rap, egg-shaped characters that get hard-boiled when stressed out, mega-robots, men who want to marry 2D anime character-ladies, and a cameo by Samuel L. Jackson.

New Books Network

Are these books literature? What is literature? If it is a created cultural aesthetic artifact, based in language and communicating something which uses all these devices in order to get an audience response well then, yes. Comics are literature. But are they good literature? That’s a different question.

OTHER REFERENCES

- Jennifer Byrne’s Presents: the episode on graphic novels with Nicki Greenberg has a transcript.

- Markus Zusak mentions Maus on the episode about ‘Cult Reads’.

- Scott McLeod’s book Understanding Comics

CARICATURES IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

Smith’s Weekly was a humorous look at Australian current affairs, the sort of thing that has been replaced by TV these days. There were cartoons, the throw-away line (Garfield style). This tabloid helped popularise this caricatured way of drawing.

Today we look at the bridge from younger readers into adult via cartoons, but maintains the features typically associated with children.

Scott McLeod: Understanding Comics is an influential book about these concepts, and it’s written in comic format itself.

What is a comic?

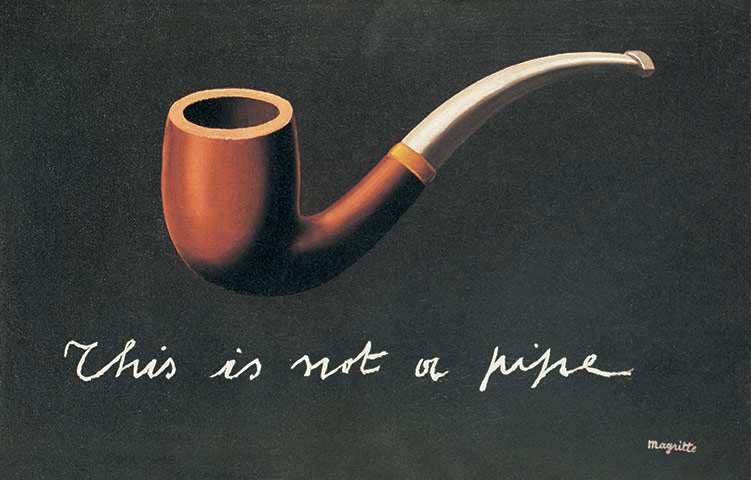

In about 1912 Rene Magritte (mentioned in Voices In The Park lecture) did a famous painting about art:

There were a lot of arguments at the time about what is art and what isn’t. Magritte of course was saying, ‘This is not a pipe; it’s a picture of a pipe.’ The artist makes you think about the object, not about the representation.

So a comic is something being represented (not real) and it is simplified right down. In terms of simplification, McLeod puts it like this: If you have an exact photographic representation only one person can be represented, but the more it is simplified, the more people it may represent — the more people are involved and engaged in the storyline, especially the universality of it. This leads into the idea of caricature: exaggerating some parts.

We know cartoons mostly as political cartoons, as adults. In our childhood there were simple storylines.

The tradition of caricatures goes right back to John Tenniel.

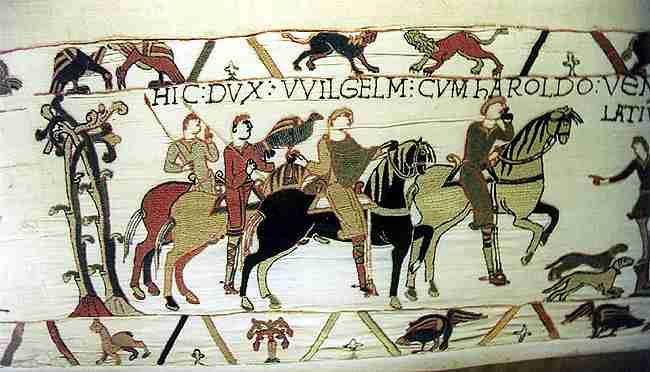

When does a caricature become a comic? The key point here is sequencing. The placing of several of these caricatured pictures in a row in order to express a relationship between them makes a comic.

One of the earliest examples goes back to the 11th century with the Bayeux tapestry.

Done like this, the time lapse isn’t that obvious. It looks like a single picture rather than the same story told over several years.

So in order to get the sequencing across, comic creators started doing something: There is an assumption when we’re very young that if we can’t see something it doesn’t exist (e.g. that’s why peek-a-boo works). The key point is that if you can’t see it, it doesn’t exist; if you can see it, it does. So now pictures follow one after each other in a temporal sequence.

Various tricks are used to indicate movement: blurring.

Line can also be used to indicate smell etc. in a mimetic way.

If the reader looks at dots and interprets those dots as flies, the reader is interpreting symbols in the same way as they are reading words.

There is a lot more, of course, but those are a couple of examples of how lines is used in the comic.

In the early 1740s when books for children started getting published, pictures were included right from the start. These were done on the cheap on woodblock prints, potato printing principle. (No colour — that came 100 years later. Any colour was usually hand done.) Very young children were employed to colour them in, sitting in sweatshops. Someone would do the blue and pass it on to the next person who would do the yellow.

After a long while printing allowed different colours on the same page.

In the 1860s two characters changed the face of children’s literature in a huge way: Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll, who with his stories illustrated by John Tenniel, really enabled this humorous aspect to take off. Prior to this the drawings had all been serious. The pictures themselves now were able to have humour inherent in them and them only, things like the facial expressions of Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee. At this stage Britain was the major economy and cultural centre of the world, so in Britain this format continued for the next century or so. This wasn’t only the case for children — magazines were big, Charles Dickens released as serials in weekly and monthly magazines. There were very specific ones for very specific groups — Girl’s Own Paper, Boy’s Own Paper, which had a huge influence. They were originally the Bible society, but in the end they were doing adventure stories and recipes. The girls’ ones are heavily about how to maintain a good house, while the boys are out in lifeboats rescuing drowned sailors or fighting pirates.

By the time mags such as Eagle (Dan Dare, sci-fi) came along the pictures had taken over.

The most syndicated and read comic would probably be Peanuts, from the 1950s to the present day.

Little Nemo In Slumberland is very modern — different size and shaped frames — this mechanism was before its time.

This comic also introduced the speech bubble — a major change in comics. There was one person per frame with one speech bubble, max.

With the narrative serial came the invention of the superhero. This hit our newspapers in the 1930s. There’s possibly a social reason: the depression (along with Shirley Temple) and the ones who are not everyday, which was pretty darned depressing, so people wanted to be removed from the reality of life.

The superhero and the supervillain were very popular in America. This can be seen even now in the difference between the crime shows. In England The Bill — ordinary people, but so many of the American ones feature a hero with a super skill (The Mentalist). The detectives and the police are super. There’s a different approach to storytelling. This is the point where children’s storytelling is now becoming adult literature.

Britain and Europe aren’t the only places this is happening. In Europe the comic developed slightly differently. It’s still very much a child’s plaything and still in serial format, but published as complete books: Asterix and TinTin are the main ones. There is also a difference in the characters. Tin Tin is quite different from Batman. The creator of Tin Tin had a special approach to Tin Tin: a lot of superhero comics are very cinematic, with close ups and panning and long shots and high views down. Sergey of Tin Tin never does that. He tends to draw everything as if everything matters, a precise, quiet style of art without the zap/pow. The reader is encouraged to really look hard at the pictures.

The Asterix books are very verbal, based on puns, particuarly around people’s names. This has led to a very interesting concept as they’ve been translated. Stephen Fry who did Planet Word asked the question: Do speakers of different language think about things differently? Asterix is written in French, so all the puns are also in French. Puns don’t work in English. You have to then find English ones which are just as funny, so translation is very difficult.

Comics now: Mainly an adult form. What used to be the Donald Duck cartoons has largely been replaced by the CGI movie format, Toy Story etc. Certainly there are kids’ programming — a lot of it is animated cartoon, but there’s not the same amount of single frame comic format designed for kids.

There are also glossy magazines such as Dolly, which is consumer driven. K-Zone etc. are largely spin offs of movies, buy this particular computer game, they are largely a marketing tool.

The movies are not kids’ movies but they are marketed to kids, in Happy Meals, in toys, so parents are caught. Even back in 1743 there were giveaways (ball for boys, pincushions for girls sort of thing). But there is now a huge amount of crossover – movies, comics, games and so on feed off each other.

There is also a huge Japanese influence from manga and anime. Take The Joker as an example, comparing the earlier movie with the new Heath Ledger one. Modern movies have more powerful emotions, more serious topics, and the printed comic is now an adult format. However, the style is still incredibly influential.

What comics do well: sequence, simplicity, suggestion by exaggeration. Terry Denton uses those formats.

by Terry Denton

Shaun Tan, too, in his picture book The Arrival draws major works of art with complexity, but they are arranged as a sequence so the comic techniques are there and they’re still being used.

RELATED

Talk to My Back

Manga historian Ryan Holmberg introduces the influential alternative manga artist Murasaki Yamada (1948-2009) to English readers through a scholarly translation of Talk to My Back (1981-1984), Yamada’s feminist examination of the fraying of Japan’s suburban middle-class dreams. The manga is paired with an extensive essay by Dr. Holmberg, in which he positions Yamada’s oeuvre within the history of alternative manga and Yamada’s manga within her life. Alternative manga is primarily associated with male artists in the United States, but Holmberg illuminates why that came to be and how that image varies from reality through his examination of Yamada’s oeuvre.

Talk to My Back (Drawn & Quarterly, 2022) portrays a woman’s relationship with her two daughters as they mature and assert their independence, and with her husband, who works late and sees his wife as little more than a domestic servant. While engaging frankly with the compromises of marriage and motherhood, Yamada saves her harshest criticisms for society at large, particularly its false promises of eternal satisfaction within the nuclear family.

New Books Network

How the visual language of comics could have its roots in the ice age: Psychologist and comics obsessive Neil Cohn believes cartoons have a sophisticated language all their own and a heritage that goes back to cave art. From The Guardian