The Gothic is notoriously difficult to define. This is a type of story in constant flux. Each new literary period adds is own spin. “Gothic” is more like a skin layered upon other genres, most often: horror, romance, science fiction and fantasy. Where does one genre end and the gothic element begin?

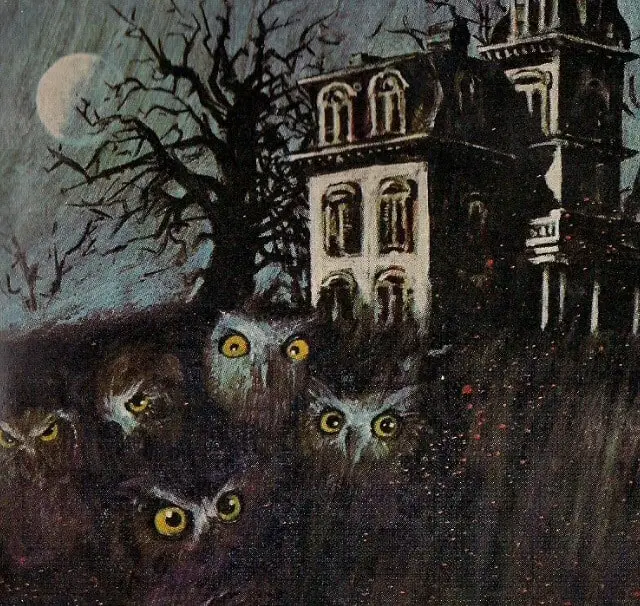

Gothic horror is also known as gothic fiction. Characters generally get caught up in paranormal schemes. The victim of these schemes is normally an innocent and helpless female character. In some instances, supernatural phenomena such as vampires and werewolves are later explained in perfectly natural terms, but in other works they remain completely inexplicable.

When romance is the main focus it’s called gothic romance. Dark paranormal romance is the new gothic romance and is a popular genre in young adult literature. When gothic is the skin of horror, it’s called “gothic horror” and so on.

Sometimes, paradoxically, a gothic chiller can be frightening and reassuring at the same time–perhaps it has something to do with striking that perfect balance between physical comfort and mental unease.

Elizabeth Brooks, The Millions

See also: What’s behind the wide appeal of all the horrible, brooding YA boyfriends?

Bear in mind, no one has yet produced a satisfying definition of Gothic which is widely agreed upon. There are even arguments about whether “horror” should be considered a necessary part of it, or whether horror is enough to call something “Gothic”. (Why not just call it horror? What special sauce makes it also “Gothic”?)

If gothic novels do not need to “look” gothic – if they do not need the ‘trappings’ (as they are often called) of castles, ghosts, corrupt clergy, and so on – then what exactly defines the genre?

Donna Heiland

Gothic stories can have any function from upholding conservative values to subverting them. The Gothic is often supposed to have emerged as a reaction against neoclassical notions of taste and propriety.

A Short History Of Gothic Horror

Gothic horror is ‘family horror’. That may sound strange, but Gothic horror relies on feminine monsters: murderous nannies who infiltrate the home, women who are monsters, houses which are feminised, women’s pregnant bodies compared to a house, you name it.

This applies to contemporary Gothic horror as much as to classic Gothic horror. Psycho is considered a turning point — the transition ‘from the family or marital comedy of the 1950s to the family horror film’ (Robin Wood, 1986). Three years after Hitchcock’s Psycho came out, Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique, which is also about a feminine transition, from ‘mystique’ to genuine empowerment.

English author Horace Walpole is thought to have kicked the gothic genre off, with his 1764 novel The Castle of Otranto, subtitled (in its second edition) “A Gothic Story.” This story originated in England in the second half of the 18th century. But it took until the late 1790s for “Gothic” to take on some of the meanings we most frequently associate with it today: Gothic as synonym for grotesque, ghastly and violently superhuman.

SO WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN ‘GOTHIC’ AND ‘GROTESQUE’?

When contemporary commentators talk about “the grotesque,” their meaning is usually closer to its adjectival form:

very strange or ugly in a way that is not normal or natural

The grotesque in literature focuses on the human body, and all the ways that the body can be distorted or exaggerated. The aim of the grotesque: to elicit empathy and disgust at the same time.

In some ways, the grotesque is similar to the uncanny. Both draw their power from the combination of the familiar and the unfamiliar, or the familiar which has been distorted. (This is called defamiliarisation, another storytelling technique much used in Gothic genres, as well as in many other types of story.)

Gothic fiction is not necessarily grotesque, but commonly contains elements of the grotesque. Mary Shelley’s monster in Frankenstein is a stand-out example. Off-kilter characters in Flannery O’Conner’s short stories would also count.

In the past, the term “grotesque” was used in a way that overlapped more with “the uncanny” when referring to works which blurred the line between the real and the fantastic. Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis” is a stand-out example here. Contemporary commentators often use ‘magical realism’ to describe this sort of story (as well as “Kafkaesque”, of course.)

All of these words — grotesque, uncanny and Gothic — are notoriously difficult to pin down because they constantly evolve over time.

Back to the history of Gothic: The Gothic continued with much success in the 19th century, with the popularity of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and the works of Edgar Allan Poe. Another well-known novel in this genre, dating from the late Victorian era, is Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

Gothic literature in Britain enjoyed a major boom in popularity during the Romantic period, and especially between 1791 and 1824. The height of the Gothic period closely aligns with Romanticism (1764-1840).

Gothic fiction focuses on the grotesque, the carnivalesque, and the darkly ominous aspects of human nature as a way to represent the implications of Romantic idealism in a world whose conditions are anything but the lofty heights of the original Romantic works. […] much of the traditionally-accepted “Romantic” works from 19th-century Spanish authors have little to do with the Romanticism of northern Europe but, instead, have much more in common with the European and American Gothic movements of the late-18th and early-19th centuries.

Heidi Backes

Because of the eras it spans, classic Gothic literature is neither properly Romantic nor properly Victorian. Writers such as Robert Browning, Charles Dickens and Charlotte Bronte made sure the Gothic tradition survived, alive and kicking, into the Victorian era. That said, it went through a lull in the early 1820s and picked up steam again by the late 1840s.

There’s a case to be made that Victorian Gothic is a whole nother thing.

The Gothic literary tradition, established in the mid-eighteenth century, was significantly reinvented during the Victorian period. This move towards a reclassification of the Gothic as distinctly Victorian supports Fred Botting’s argument for a re-evaluation of the Gothic and a break away from more familiar modes of criticism. He suggests that the Gothic aesthetic, as well as the novel, has fake origins in the eighteenth century. This, he argues, is due to its literary reinvention of the medieval period that vastly predates the period in which it was written. With this in mind, all Gothic fiction may be deemed a mere reconstruction or reinvention, and the eighteenth-century origination of the Gothic novel an unauthentic and unreliable basis for the examination of subsequent Gothic texts. The Victorian Gothic, I will contend, dealt with different cultural anxieties and embraced theoretical or philosophical studies not yet available to writers of its eighteenth-century predecessor. Therefore, I will attempt to address the following questions: What constitutes Gothicism or the Gothic aesthetic in Victorian writing, specifically in relation to sensationalism, and science and the sublime? What contemporary criticism on the Gothic, nature and science were Victorian writers engaging with? How does a new reading of nineteenth-century writing within the context of the ‘Victorian Gothic’ challenge our perceptions of the Gothic, and how will this affect future analyses of Victorian Gothic literature

Rachel Mace

Some commentators have noticed that Gothic fiction becomes more popular when times are especially uncertain.

If the 1970s (think the oil crisis, Watergate, a spike in “skyjackings”) primed readers to be receptive to [Gothic] elements, it was a decade destined to be far outdone by the start of the 21st Century in terms of horror and upheaval (9/11, the global financial crisis, an intensified fear of climate apocalypse). The world seems to have grown only more uncertain in the years since, and it’s certainly tough to rival the age of Covid for gothic motifs made manifest. Claustrophobia? Try successive lockdowns spent working, learning, and socialising from home. Isolation? Ditto. Fear of a past that can’t be exorcised? Sounds a lot like “long Covid”.

By Hephzibah Anderson, Why We Are Living In ‘Gothic times’

The word “Gothic” also refers to the (pseudo)-medieval buildings, emulating Gothic architecture, in which many of these stories take place.

When the Gothic was emerging as an important genre in its own right, medical science was just starting to replace the mystery of the female body with scientific facts. Hysteria was the dominant response to sexual confusion and abuse. Encoded in law, marriage meant a loss of power and autonomous identity for women. Pregnancy and childbirth were downright dangerous, messy and awful. Today things are a bit different: We understand (basically) how the body works. We know that hysteria is an unhelpful, outdated word for what is actually a collection of disparate conditions. Many women are brought up to believe we can have it all (itself a kind of fairytale). But we still live in a patriarchal world. Classic Gothic ideas are still recognisable to modern readers.

Gothic motifs change rapidly and consistently, both in form and in significance. It all depends on what is feared and valued at any given time. The Gothic genre is especially responsive to historical moment and cultural location. Patricia Murphy has said that “a truism of critical commentary holds that the gothic emerges in literature during times of cultural anxiety.” (Zombie stories are another example of this.)

For example, the 1970s saw a lot of ‘bodice rippers’ which were replaced in the 1980s by a revival of gothic romance in the Harlequin series. Plots reflected a rising divorce rate in the West.

These days, readers are unwilling to unilaterally assign blame to one character in a Manichean view of human nature. Even in children’s literature, with perhaps a slightly higher tolerance for ‘black and white’ morality, the opponent web is more complex than ever. Even if a story contains a Minotaur opponent (pure bad), there will be other more nuanced opponents. These characters are not inherently evil, but behave badly as a result of their environment. When writers create fictional characters, they usually hint at how they became that way, by giving them a ‘psychic wound‘ (sometimes called ‘fatal flaw’ or ‘ghost’).

The ‘innocent’ victims, too, are afforded some dignity in that they are assumed to have some part in their own predicament. In other words, modern victims have a psychological and moral shortcoming, whereas earlier victims were more ‘victim-y’ and more boring as heroes, to be fair. Though it may seem counterintuitive, characters with moral shortcomings are more likeable.

Modern gothic stories don’t seek to expel evil completely, but rather to accommodate it and give it its own space. Modern gothic stories are about finding some sort of middle ground.

Intertextuality is an important element of Postmodernism and also of Gothic texts. We see that in modern TV series Supernatural, which features ‘meta-episodes’.

Everyday Usage of The Word ‘Gothic’

Modern readers and critics have begun to think of “Gothic literature” as any story that uses an elaborate, opulent setting, combined with supernatural or super-evil forces against an innocent main character. We also associate Gothic with Goths, who are pale, wear a lot of black, and reject mainstream culture as default.

See my post: What’s a Goth?

Natalie Wynn succinctly describes the sensibility of gothic as ‘ruined opulence’, and speculates we may soon see the gothic in abandoned shopping malls.

Raison d’être Of Gothic Stories

Classically Gothic settings (falsely) reassure us that ‘monsters’ are inhuman, and can be recognised quite easily. In reality, monsters are not so easily recognised:

You don’t find [monsters] in gothic dungeons or humid forests. You find them at the mall, at the school, in the town or city with the rest of us. But how do you find them before they victimize someone? With animals, it depends on perspective: The kitten is a monster to the bird, and the bird is a monster to the worm. With man, it is likewise a matter of perspective, but more complicated, because the rapist might first be the charming stranger, the assassin first the admiring fan. The human predator, unlike the others, does not wear a costume so different from ours that he can always be recognised by the naked eye.

Gavin de Becker, The Gift Of Fear

The effect of Gothic fiction feeds on a pleasing sort of terror, an extension of Romantic literary pleasures that were relatively new in the 19th century. The word for this is ‘horripilation’.

The Gothic releases forces which are usually repressed. In the Gothic, anarchy is loosed and contained at the same time. In Gothic, we have the return of whatever’s been repressed. (If you want to stay away from Freudian terminology, you can talk instead about a more general ‘return’.) Our enjoyment of Gothic horror is visceral. We enjoy the cracking of bone and the snapping of backs and the spilling of blood. The appeal has something to do with lack of restraint, transgression, the overturning of normalcy. Taboos are broken. In this respect, the Gothic is related to the carnivalesque.

Related to repression in general, the Gothic is about our fear of the past returning, which in turn is about our thoughts around humanity’s hereditary animal nature. We sit uncomfortably with the fact that we are so closely related to other animals.

The Gothic is also a form known to examine our fear of desire. Some have even called the Gothic form the ‘literature of desire.

An interesting thing about Gothic stories: They find popularity among woman readers at times of social change and much talk of feminism. For some people, this feels like a contradiction, because Gothic stories aren’t generally known for being bastions of feminist thought. Here’s a theory:

[Gothic literature] accepts our stereotypes — such as the high value we place on good loocks, or our cultural sex-role stereotypes — but insinutates that the reader can beat the system, whether through talent or through such loopholes as luck or socially advantageous marriage.

Kathryn Hume, 1984

Might we apply a similar theory to why true crime attracts such a large woman audience, even when most of the victims of crimes explored are women?

Stories about monstrous women are especially popular when the rights of women are in flux.

‘Gothic’ is also a book marketing term, used to describe any book likely to appeal to the demographic of white middle-class women whose primary concerns include caring for house and family. The psychological needs addressed by these books are what we might expect from someone with that kind of life. In interview, Margaret Atwood used a phrase ‘slightly prefeminist women’, which describes women whose lives would be very much improved with feminist advancement, but who aren’t in a place to confront the issues head on (I suggest because that would spark so much unbridled rage).

The first modern novel to be called ‘Gothic’ was Mistress of Mellyn by Victoria Holt, published 1960.

Common Features Of Gothic Stories

Though some commentators stop at saying the Gothic is about unknown, unnamed fear, others have created a lengthy list of features common to Gothic stories, or, what we have collectively mostly decided should be called Gothic stories.

PARODY

There is much parody within the gothic genre, including parodies of parodies. Authors send up other work by writing a supernatural gothic romance. Ironically, later audiences assume they were meant to take these old parodies seriously, and subsequent authors make parodies of that ‘original’ parody.

Some commentators feel that ‘pastiche’ is a more appropriate word than ‘parody’ when describing how Gothic stories borrow from earlier stories.

When creating pastiche, Gothic writers commonly borrow the following:

- Parts of folk tales

- Songs

- Old wives’ tales and superstitions

- scientific enquiries

- theology

- graveyard poetry

- Sturm und Drang German romanticism

- the literature of sensibility (the Sentimental novel is an 18th C genre)

- theories of the sublime

- travel guides

- dictionaries

- legal and religious testimony

- melodrama

The reason we should probably call these elements pastiche rather than parody: The Gothic texts which utilised them pretty much presented them at face value without offering commentary or encouraging criticism.

PARANOIA

The Gothic is basically ‘paranoid‘. But only if you immerse yourself too much in it, succumbing to its fears. Modern mass media itself might be accused of being Gothic, with its emphasis on the macabre.

Gothic stories are popular at times of great technological change. The Gothic flourished during the period of early industrialised capitalism. This was the age of Enlightenment, when science was influencing social change.

Information revolutions bombard us with sensory overload. We feel everything’s changing so quickly and we can’t keep up. We tend to feel like ‘They’ are doing stuff behind the scenes and for all we know They are up to no good. Paranoia, in other words.

The popularity of Gothic stories make more sense when considered in the light of a paranoid reading public. The Gothic villain plots away behind the scenes. To be fair, people did have knowledge of the Holy Inquisition, which wasn’t great. Talk about dangerous master plotting:

The Inquisition was a powerful office set up within the Catholic Church to root out and punish heresy throughout Europe and the Americas. Beginning in the 12th century and continuing for hundreds of years, the Inquisition is infamous for the severity of its tortures and its persecution of Jews and Muslims.

History

SUBLIME

The Gothic is also often described as ‘sublime‘, which you may realise means something slightly different when it comes to literature.

In everyday English, sublime might mean ‘really wonderful’ but in literature it refers to work which provokes terror and pain in the audience. Terror and pain are the two emotions considered most powerful. Unlike the terror and pain of the real world, however, when experienced via story the audience enjoys it very much.

The sublime is a feature of Romantic work.

UNCANNY

‘Uncanny‘ is another word you’ll hear in reference to the Gothic. The uncanny is a psychological concept which refers to something that is strangely familiar, rather than simply mysterious. The feeling emerges from something which has been repressed.

One good method of making something seem strangely familiar: doubling e.g. doppelgangers.

The emotions evoked in a work of Gothic fiction will be familiar to you. You may not have seen an actual ghost, but you will have experienced horripilation — that feeling of hair standing on end.

Gothic works connect to cultures of their authors, and each culture has its own way of relating to the uncanny. Take Mexico, for instance. In Mexican Gothic, authors make use of certain features of Mexican history: ritual sacrifice, the dual nature of Aztec gods, the liminal space between life and death, and an interweaving stance in regards to cyclical and linear time.

BURIED OMINOUS SECRET

The ‘buried ominous secret’ is Joanna Russ’s term for what is basically some kind of mystery. This mystery will be connected to The Other Woman and the Super-Male. The virginal maiden will try to get to the bottom of this secret but ends up in need of rescue. The real hero will end up saving her. Now she knows which of the men is the goodie.

Gothic writers typically set off one account of events against another, asking the reader to guess at or deduce which account is the truth.

This part of the story will typically be subsumed by a ‘master narrative’ whose unseen narrator fails to pick up what the reader hopefully has. This failure allows access to a myterious other realm.

A thrilling Gothic tale from the author of Our Castle by the Sea, shortlisted for the Waterstones Children’s Book Prize.

1899. The Earl of Gosswater has died, and twelve-year-old Lady Agatha has been cast out of her ancestral home – the only home she has ever known – by her cruel cousin, Clarence. In a tiny tumbledown cottage, she struggles to adjust to her new life and the stranger who claims to be her real father.

And on the shores of Gosswater Lake, the spirit of another young girl will not rest. Could the ghost of Gosswater hold the key to Aggie’s true identity?

Wait Till Helen Comes is a surprisingly dark middle grade novel from the 1980s, later adapted for film.

Beware of Helen…

Heather is such a whiny little brat. Always getting Michael and me into trouble. But since our mother married her father, we’re stuck with her…our “poor stepsister” who lost her real mother in a mysterious fire.

But now something terrible has happened. Heather has found a new friend, out in the graveyard behind our home — a girl named Helen who died with her family in a mysterious fire over a hundred years ago. Now her ghost returns to lure children into the pond…to drown! I don’t want to believe in ghosts, but I’ve followed Heather into the graveyard and watch her talk to Helen. And I’m terrified. Not for myself, but for Heather…

Gothic children’s books often feature orphans.

‘[The orphan] focuses on a self-pity that everyone wants to feel sometimes, and that perhaps helps a child or an adolescent to think through their fundamental separateness.’

The Child that Books Built, Francis Spufford

The Victorians had what one might call a morbid obsession with death and the rituals surrounding it. This obsession included memento mori —from the Latin phrase meaning “remember your mortality,”— or relics of the dead most often in the form of jewelry made with the deceased’s hair. But more than reminding the wearer of his or her own mortality, these relics provided a link to the dead. This practice reveals the Victorians’ deep desire for these material remains to prove the continued existence of the loved one from whose body it came in the spirit realm. Spiritualism and séances solidified the importance of the relic as proof of eternal life. The Victorian desire for a connection to the dead is not unlike our own, although our online culture seeks a direct, digital link to the dearly departed.

Jeanette A. Laredo

See also: Victorian Seances, episode 115 of Then Again Podcast with Lesley Jones.

Maud Flynn is known at the orphanage for her impertinence, so when the charming Miss Hyacinth and her sister choose Maud to take home with them, the girl is as baffled as anyone. It seems the sisters need Maud to help stage elaborate séances for bereaved, wealthy patrons. As Maud is drawn deeper into the deception, playing her role as a “secret child,” she is torn between her need to please and her growing conscience – until a shocking betrayal makes clear just how heartless her so-called guardians are. Filled with tantalizing details of turn-of-the-century spiritualism and page-turning suspense, this lively historical novel features a winning heroine whom readers will not soon forget.

Laura Amy Schlitz uses Victorian Gothic really skilfully in her books. The advantage: Writers don’t have to wrestle with technology in the story and this historical setting is dark and mysterious, very colourful, and lends an air of fantasy.

The master puppeteer, Gaspare Grisini, is so expert at manipulating his stringed puppets that they appear alive. Clara Wintermute, the only child of a wealthy doctor, is spellbound by Grisini’s act and invites him to entertain at her birthday party. Seeing his chance to make a fortune, Grisini accepts and makes a splendidly gaudy entrance with caravan, puppets, and his two orphaned assistants.

Lizzie Rose and Parsefall are dazzled by the Wintermute home. Clara seems to have everything they lack — adoring parents, warmth, and plenty to eat. In fact, Clara’s life is shadowed by grief, guilt, and secrets. When Clara vanishes that night, suspicion of kidnapping falls upon the puppeteer and, by association, Lizzie Rose and Parsefall.

As they seek to puzzle out Clara’s whereabouts, Lizzie and Parse uncover Grisini’s criminal past and wake up to his evil intentions. Fleeing London, they find themselves caught in a trap set by Grisini’s ancient rival, a witch with a deadly inheritance to shed before it’s too late.

Orphaned children are streetwise, but whether orphans or not, children in contemporary Gothic literature know ‘too much’. Gothic texts have “a particular emotive force for us because [they bring] into high relief exactly what the child knows… Invariably, the Gothic child knows too much, and that knowledge makes us more than a little nervous,” writes Steven Bruhm in an article called “Nightmare on Sesame Street: or, the Self-possessed Child” (Gothic Studies 8, no.2, 2006).

SEPARATION

Notably: Gothic stories do not divide, but rather integrate the Self and the unknown Other. The Gothic has continuously presented characters destroyed by their own self-recreations e.g. Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, House of Leaves.

Desire plays a big part in feminine Gothic fiction. In Gothic texts there is generally some kind of violent separation at the beginning. In fact, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick has gone so far as to say that separation is one of the most characteristic gothic conventions.

Examples

- Separation from mother through death (The Mysteries of Udolpho, though dead mothers are rife throughout the history of storytelling)

- Separation from daughter through imprisonment (Maria)

- Separation from creator through abandonment (Frankenstein)

- Separation from family through exclusion (Jane Eyre)

FULL USE OF THE SENSES

Gothic places us in the darkness of vaults and graveyards. Deprived of sight, we must rely on our ears. But the eerie sounds of Gothic elude description and language, as the genre privileges sounds that seem to be dark themselves. How can we describe the sonorities of church organs, of bat wings, of hollow voices? Why are these dark sounds so profoundly destabilising? […] the ungraspable quality of timbre is the nebulous heart of the genre’s undoing of time, space, and subjectivity. Timbre itself cannot be described except in visual metonymy of “tone colour,” and in its strange inherent veiledness it is a key vehicle for the Gothic. Unable to capture in words or acknowledge what we hear, where and even when these sounds occur, our grasp of the here, the now, and the self is gradually obfuscated as we dissipate into the sonic abyss that surrounds us. A portal to the sonic numinous, timbre affords a Leibnizian fold into an outside that never existed…

Isabella van Elferen

(Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz was a polymath. One of his ideas was that our world is, in a qualified sense, the best possible world that God could have created.)

Typical Character Archetypes

Critics disagree about much when it comes to defining “Gothic” but most agree that the Gothic archetypes (or stereotypes if you prefer) are the defining feature.

The basic cast of characters:

Virginal maiden

Young, beautiful, pure, innocent, kind, virtuous and sensitive. She is also lonely.

These heroines tend to be orphaned, abandoned, or somehow severed from the world, without guardianship.

They are written to have emotional extremes. The word ‘melodramatic’ might be applied to these characters but in fact, melodrama describes a (very common) type of story, not a character. Perhaps it’s because of the traditional Gothic virginal maiden and her emotional extremes that we now think in terms of ‘melodramatic reactions’.

She is unable to rescue herself from danger. She is a damsel in distress. If she is ‘truly’ innocent, she is rescued. If she is not truly innocent, she fits one of the female archetypes below, and her story will be a tragedy.

The story usually starts out by suggesting a mysterious past. It will later be revealed that the virginal maiden is the daughter of an aristocratic or noble family. Modern stories such as Harry Potter borrow from the Gothic. We don’t think of the Grimm fairytales as Gothic, but a lot of them follow this exact plot.

The Final Girl describes a female archetype who is the last to find herself alive in a slasher film. The Finale Girl closely fits the Gothic Virginal Maiden archetype. Note that even when the Final Girl is able to slay the monster, she’s often in some remote location and will need rescuing at the very end to get back to civilisation.

The Other Woman

In Gothic romance, there needs to be a romantic rival for the virginal maiden. These women are “beautiful, worldly, glamorous, immoral, flirtatious, irresponsible, and openly sexual” (Joanna Russ). “She may even be adulterous, promiscuous, hard-hearted, immoral, criminal or even insane”.

The Young Girl

Also in Gothic romance, there will often be a girl who the virginal maiden feels the need to protect. Not a romantic rival. The virginal maiden now has the opportunity to show us how good a mother she’d make. This also functions as a Save The Cat thread.

Older, foolish woman

Or the Madwoman, or the Old Wife. Interestingly, British culture consistently associated ghosts and children with the oral tradition in storytelling. These stories were delivered by a greatly misunderstood figure: The Old Wife. The Old Wife was the woman in your community who dished out advice and help to do with childbirth, herbal remedies and so on. She lost a lot of respect, as well as her place in her community, with the emergence of modern day science.

This coincided with a growing distaste for people who believed in ghosts. Shakespeare himself poked fun at the Old Wife who believed in ghosts. You can see him doing that in Macbeth, The Winter’s Tale and The Tempest. Women, ghost stories and oral stories were connected. When one lost status, so did the others. Even in the gothic stories themselves, the Old Wife character (who told these very tales) was made fun of.

Hero

Like the virginal maidens, the hero was innocent, plunged into a weird situation. Gothic stories are melodramatic stories, and in classic melodrama, the main character reacts to crises. The classic hero drives the action, deliberately setting out into the world. In those stories there’s no pull factor, but rather a push factor: to escape the feminine realm of mother and home.

In a Gothic romance, the hero is the male love opponent. So, what’s the difference between a Gothic male love interest and a guy out of a Harlequin romance?

Someone’s trying to kill me and I think it’s my husband.

Joanna Russ, parodying the thought process of virginal maidens who realise they’re in love with a dangerous brooding man.

The Gothic romance is all about how love transforms into fear. The virginal maiden is scared by the object of her affection. She learns he can harm her. In contrast, fear turns into love in contemporary Harlequin romances. And the modern heroine isn’t necessarily afraid of the man, but afraid of losing herself to love because she’s been hurt in the past, or something like that.

These Gothic heroes, who inspire fear in virginal maidens, are often called Byronic heroes. Think Edward Rochester (Jane Eyre) and Max de Winter (Rebecca).

Tyrant/villain

In a Gothic cast, the villain is the most interesting character.

He is endlessly resourceful. He inspires awe. The audience won’t be able to easily guess his evil plans. He is mysteriously attractive.

He tends to wear a monastic habit with a cowl (a large, loose hood).

With the exception of a few novels, such as Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla (1872), most Gothic villains are powerful males who prey on young, virginal women. This dynamic creates tension and appeals deeply to the reader’s pathos.

Joanna Russ divided the Gothic villain into two main types:

- SUPER-MALE: “an older man, a dark, magnetic, powerful brooding, sardonic…who treats [the virginal maiden] brusquely, derogates her, scolds her, and otherwise shows anger or contempt for her. The Heroine is vehemently attracted to him and usually just as vehemently repelled or frightened.”

- SHADOW-MALE: “a man invariably represented as gentle, protective, responsible, quiet, humorous, tender, and calm”.

You’re probably already thinking of Twilight and 50 Shades of Grey.

It would be too predictable if the super-male always turned out to be the real baddie and the shadow-male always turned out to be the goodie, so stories mix them up. In classic Gothic, it was often the harsh man who turned out to be the nice one. (Darcy, anyone?)

Even today, crime fiction focuses heavily on victims which are young, attractive, female (and white). We seem more interested in their deaths than in deaths of other demographics.

The modern antihero (or hero-villain if you prefer) comes from the Gothic tradition. However, in gothic stories morality is clear. Good is good, evil is evil, even if it is attractive. Evil is not simply misunderstood, it is inherent. Evil cannot be assimilated into everyday society and must be expelled. That’s not how modern stories about anti-heroes typically play out. Viewers were encouraged to understand Walter White and Tony Soprano. Thinking individuals are much more yin-yang about people these days. Less nature, more nurture — even if you’re a nature over nurture sort of person, you probably admit that Tony Soprano’s life would have panned out differently had he not grown up in the mafia.

Bandits/ruffians

These opponents add interesting complexity to the web of opposition. They are less powerful than the main tyrant/villain.

Clergy

Clergy in Gothic stories are always weak, usually evil.

In Medieval times, Monks often were pretty evil. They were rich and pampered. They sequestered funds for themselves (while amazingly often managing to bankrupt the abbey by doing stupid things with money), and sometimes even harboured criminals.

Monks were supposed to live simple lives, but found ways around every rule, including the invention of a sort of sign language to get around the rule of no communication over mealtimes. It’s easy to see how the clergy became figures of fun. By early modern times, people had learned to put far more faith in nuns, more likely to behave properly according to the church.

Soldiers

The soldier, be it in the guise of an ancient knight, clansman or chevalier, appears frequently throughout the [classic Gothic] period. […] the Gothic of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century employed the soldier and the military, particularly in the context of the mounting tensions with post-Revolutionary France and the resulting Revolutionary Wars, to redefine and reconsider masculinity but also to return social value to the soldier and reconfigure him as heroic.

Daniel Southward

Servants

Like peasants, and old women, servants are socially liminal characters.

Servant characters in early Gothic literature fulfill a crucial role as in-text storytellers whose narratives often reflect larger political and literary goals and illuminate the mechanics of the Gothic mode. In acting as metonym authors, oral storytellers, and theatrical performers within specific novels, Gothic servants assumed an ambiguous position between their ostensible source material, the ‘ancient romances’ of the early modern period and earlier, and their newer post-Enlightenment innovations. Most specifically, their use of servant narrators as representatives of a literary tradition of romance and oral tales of the fantastic suggest are evaluation of these older forms as part of an attempt to define a “new species of romance”.

Kathleen Hudson

Socially liminal characters are frequently used to add stories-within-stories to a narrative (or to create diegetic levels).

Horace Walpole, Ann Radcliffe, Matthew Lewis and Regina Maria Roche all used servants as narrators.

A Note On Black Characters In Gothic Fiction

Black Gothic fiction turns to the folklore of the African Diaspora to enrich its narrative; tricksters, conjure women, and various haints wander across the pages of Black Gothic texts from the Caribbean to the U.S. to Britain. Such fiction place these characters and tropes in direct competition with traditional Gothic themes and elements, juxtaposing cultural and genre traditions in their expression of the horror of modern Black existence. In some ways, these two distinct lines of tradition allude to the hybridity which defines Black existence after slavery and colonization; yet Black authors more importantly suggest that the European narrative traditions and Gothic tropes are themselves a kind of uncanny illegible manuscript that misleads and dooms Black subjects to horror. […] Thus Black authors imply that there is no, and never has been, any legitimate space for the Black body to truly exist in traditional narratives and forms from Imperial cultures. The appearance of the African Diasporic folk text among Black Gothic narratives rather exists as an alternative knowledge system, one that liberates Black subjects from their cursed positions as monstrous “others” in traditional European Gothic and folk traditions.

Maisha Wester

Gothic Stories And Madness

American Gothic in particular tends to deal with a “madness” in one or more of the characters. An early example is the novel Edgar Huntly or Memoirs of a Sleepwalker by Charles Brockden Brown. Two characters slowly become more and more deranged.

- Sunset Boulevard — Since Boulevard’s original film release, the role has become famous for its tragic, hysterical femaleness, and is for that reason vulnerable to one-dimensional renderings of empty, and even harmful, stereotype. Sunset Boulevard subtextually warns that a woman’s ambition, creativity, and desire for sexual fulfilment are the causes of unhappiness and undoing.

- Fatal Attraction — While Norma of Sunset Boulevard is an artist, the madwoman of Fatal Attraction is a professional.

- Black Swan

- Flowers In The Attic by Virginia Andrews

- Apocalypse Now

- The Shining by Stephen King — Isolation is used as a vehicle for madness. (Used again more recently in Shut In.) The main character is Jack Torrence, played by Jack Nicholson in Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation. With his family he looks after an empty hotel one winter, partly to concentrate on writing his novel. But he is haunted by visions and descends into murderous madness.

- Carrie by Stephen King, which promotes anxiety and thereby encourages conformity. A good example of ‘suburban Gothic’, making use of Gothic features such as witch-hunting.

- Misery by Stephen King

- The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, who was herself diagnosed with hysteria and commanded never to touch pencil and paper again.

- Shut In — Naomi Watts plays a widowed child psychologist who lives in isolation in rural New England with her son, who is comatose and bedridden as a result of an automobile accident. Snowed in and withdrawn from the outside world, Watts’ character descends into a desperate existence. It soon becomes difficult for her to distinguish the phantasms of her imagination from the reality of the creepy goings-on in her apparently haunted house.

WHAT IS ‘FEMALE GOTHIC’?

Apart from hotly contested, that is?

This terminology is a long-term topic of debate yet people keep using it. When using it in a paper, you have to define what you mean by it first.

Many people using the phrase ‘female gothic’ are talking specifically about quite a diverse group of female writers working in Britain in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century:

- Clara Reeve

- Ann Fuller

- Ann Radcliffe

- Mary Robinson

- Mary Hays

- Charlotte Dacre

- Mary Shelley

When talking about the female gothic outside this time period, others include writers such as Virginia Woolf, whose work might be said to have a Gothic aesthetic: An uncanny effect of terror for readers.

FEMALE GOTHIC CHARACTER ARCHETYPES OF STEPHEN KING

Stephen King is an especially popular writer of contemporary Gothic fiction and deserves further mention.

While classic Gothic has only two adult female archetypes, the Virginal Maiden and the Other Woman, Stephen King uses three stereotypes:

- Monster: Women who shun or distort the criteria of the domestic test. The audience is invited to pass dark judgement on these women. They are human villains. They are feminine in gender, but have no feminine virtues at all. IT is a standout example, and a hideous inversion given that it targets children. (Throughout the novel, IT is generally referred to as male; however, late in the novel, the characters come to realize that IT is most likely female, due to its true form in the physical realm being that of a giant pregnant female spider.) The fear of women’s bodies has been a recurring subject of writers of Gothic fiction more generally. (For more on that, see the work of Barbara Creed, who talks about Kristeva’s paper about the abject.)

- Helpmate: the most common female character in Stephen King stories. She aspires to be a good wife and mother and does well on the domestic test. The better they do on the domestic test, the better their outcome in the story. These women step back and let the men take care of the beasts. Not all helpmates are successful. Donna Trenton of Cujo is a failed helpmate. She waits too long before trying to save her son. Women who behave like children (rather than providing safe refuge from their men) are also failed helpmates. Traumatised women behaving like children are also punished (Rachel Creed). Rachel Creed is an extreme version of the failed helpmate and descends into monstrosity.

- Madonna: much less common in Stephen King stories. Normally when we talk about Madonna characters we mean women who are pure and chaste, but this isn’t exactly what Pharr is talking about. Sex is liberally sprinkled throughout Stephen King’s stories. He doesn’t tend to write non-sexual women. This Madonna character is like a super-helpmate. She is so good at being a helpmate that she is above reproach. Stephen King doesn’t give her a moral shortcoming. Sasha from Eyes of the Dragon is a Madonna: perfect wife, mother and homemaker.

Critic Mary Pharr classified King’s female characters into Monster, Helpmate and Madonna.

Pharr makes use of Kay Mussell’s “domestic test”, equating a female character’s goodness and likeability with how well she fulfills the roles of homemaker, wife and mother. Often in stories, if a female character fails on one of those areas, her story ends up a tragedy.

Ideally, women provide such a respite for their mates and their young. This role is enormously important and never intentionally patronizing. Its defect, however, is also enormous: it determines a woman’s worth exclusively by her domestic success or failure rather than by any achievements she may have as an individual. The domestic test is, finally, a very narrow, very tough way to judge any human being, even fictional ones.

Mary Pharr

As we learned from Misery, the story of the woman who holds a man captive can never be a glamorous one. Over the course of Stephen King’s 1987 novel, we’re led to understand that Annie’s insanity—her insecurity, her obsession—is inextricable from that which makes her unlovable, a given long before she ever stumbles across the luckless object of her affections, her favourite writer, in the wreckage of his car. Dowdy and deranged, Annie forces him to rewrite his final novel according to her whims, crooning, “I’m your biggest fan,” over his tortured body.

And indeed, what could be beautiful or romantic about a woman with the violent upper hand, the muse forcing herself on the artist—never mind that the gendered inverse (see: Scheherazade’s dilemma) is the stuff of literature? A story about woman holding a man against his will, especially if she seeks to exploit his creative labor…Well, that’s just crazy. And for women, crazy, as we all know, is not a Good Look.

from Davey Davis writing at The Millions

Davis is writing about the gendered nature of craziness:

- Humanity is not something the crazy woman is typically afforded

- This ‘madwoman archetype’, or the idea that a woman who desires (what she doesn’t have; what she shouldn’t want; what is inconvenient or dangerous for male authority) must be institutionalised, silenced, or worse — is deep in the bedrock of our culture.

- Even now, the two attributes of women most feared (by the dominant culture and by women ourselves) are ugliness and craziness. Infertility is linked to ugliness, which is linked to old age. Old age is linked to death, the most scary thing of all.

Settings Of Gothic Horror

In general, the settings of Gothic stories focus on the archaic in some way.

The setting of the Gothic novel is a character in itself. The setting not only evokes the atmosphere of horror and dread, but also portrays the deterioration of its world. The decaying, ruined scenery implies that at one time there was a thriving world. At one time the abbey, castle, or landscape was something treasured and appreciated. Now, all that lasts is the decaying shell of a once thriving dwelling.

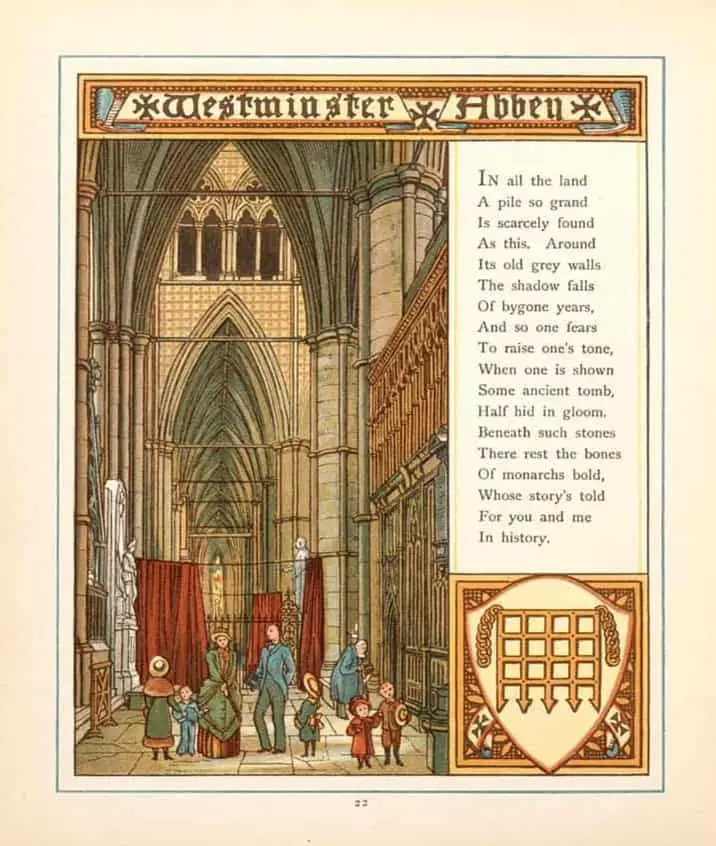

The term “Gothic” originates with the ornate architecture created by Germanic tribes called the Goths. It was then later expanded to include most of the medieval style of architecture. The ornate and intricate style of this kind of architecture proved to be the ideal backdrop for both the physical and the psychological settings in a new literary style, one which concerned itself with elaborate tales of mystery, suspense, and superstition.

ThoughtCo

In addition to the forests and vast gardens where untamed nature is controlled, the castle is one of the most suitable places to evoke the semantics of the multiple: the numerous galleries and rooms are arranged like a labyrinth and the catacombs make up other hidden and unexplored ones. The multiplicity of spaces in castles can only be seen by those who inhabit them; outsiders only intuit an elusive number of dim rooms, which give rise to irrational fear of the unknown and the uncontrollable.

Multiplied Horror An Isotopy In Three Stories By Lovecraft, Academia.edu

The building might be:

- a large castle or estate set in the wilderness, far away from neighbours or cities

- an abbey

- a monastery

- crumbling battlements

- ruined dwellings

- prisons

- abandoned hospitals

- or some other, usually religious, edifice

Buildings will probably be in need of repairs, even if they’re not actually abandoned. Ruins, dungeons, darkness and largeness are key to setting the Gothic mood. Owners have a lot of economic capital and power to ruin others. Or perhaps the owner used to possess considerable wealth, but not anymore.

This building will have secrets of its own, and can therefore be considered a character in its own right (with psychological/moral needs and desires). These Building Characters even have names of their own. They seem to “brood”. In feminist Gothic fiction, the house may be an outworking of the female body, with its ability to ‘house’ others (via pregnancy).

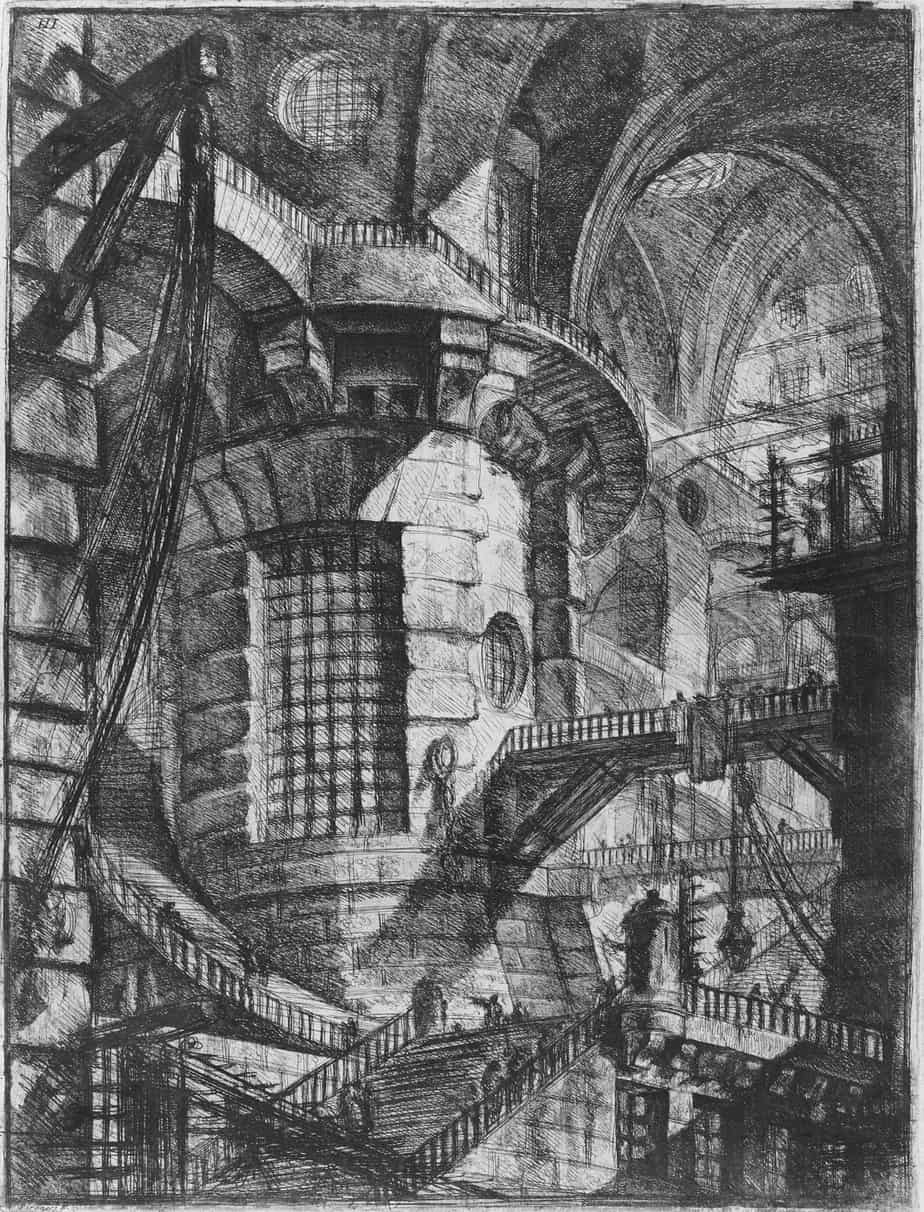

The castles and monasteries of classic Gothic are in some way exotic. They’re not typically written by authors with excellent architectural knowledge themselves, but by writers whose idea of castles and monastaries have been influenced by the etchings of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720 – 1778), who was himself an architect.

These scenes play with tidbits from imagined feudalistic and Medieval histories which are remixed for maximum playfulness. The readers of these stories were living in the age of industrial capitalism, whose idea of the past didn’t exactly hew to accuracy.

Painters such as Henry Fuseli (1741 – 1825) were also creating for industial capitalist audiences a ‘Gothic’ idea of the past.

Other settings may include caves or the wilderness, metaphorical spaces which are as old as storytelling itself.

Plot Structure Of A Straight-up UNIRONIC CLASSIC Gothic Story

WEAKNESS: A female character is an innocent, unwitting victim with no particular moral shortcoming but she is weak in general owing to her position/station in life.

DESIRE: She (perhaps subconsciously) wants to be saved from her ordinary life. This is the same wish-fulfilment as modern dark, paranormal romances, and is easy to mock until you understand that this desire is borne of a need to escape, because adolescence is terrifying for a girl whose body is suddenly attracting the attention of much larger, stronger men, some of whom will not leave her alone.

OPPONENT: She is the victim of some sort of external malevolence.

ALLY: A rescuer arrives from outside.

BIG STRUGGLE: There is a climactic encounter between the forces of evil and the forces of good.

NEW SITUATION: The evil is now expelled completely.

Symbol Web Of Gothic Horror

Night journeys

Journeys that take place overnight are a common element seen throughout Gothic literature. They can occur in almost any setting, but in American literature are more commonly seen in the wilderness, forest or any other area that is devoid of people.

Evil characters

Evil characters are a particular feature of American Gothic. Depending on the time period that the work is written about, the evil characters could be characters like Native Americans, trappers, gold miners etc.

Omens

Omens, portents, visions, etc. — often foreshadow events to come. They can take many forms, such as dreams.

Miraculous survivals

Shy, nervous and retiring heroines are nonetheless equipped with the remarkable ability to survive, even in the most hideous and dangerous situations.

An element of fear

Commentator Scott McCracken says, “The central and indispensable element of gothic horror is fear.” While fear is present in every Gothic story, not every story about fear is Gothic. Some say that fear is Gothic if human characters don’t understand the source of the fear.

To that I would ask, don’t we already have a word for that kind of fear? See: What Is Cosmic Horror?

In any case, this fear can lead characters in Gothic stories to commit heinous crimes. Brown’s character Edgar Huntly is driven by fear when he contemplates eating himself, eats an uncooked panther, and drinks his own sweat. (Memoirs of a Sleepwalker is a 1799 novel by the American author Charles Brockden Brown.)

Psychological overlay

Characters within an American Gothic novel are affected by things like the night and their surroundings. An example: A character is in a maze-like area. The story makes a connection between the outer world of incomprehensible path, and the maze-like confusion (inside the character’s mind).

The Other

Frederike van Leeuwen said in 1982 that women’s Gothic fiction is ‘the discourse of the Other’. Frankenstein is an early and tentpole example of this. You’re likely familiar with the following famous paragraph from Mary Shelley’s classic:

I am alone and miserable; man will not associate with me; but one as deformed and horrible as myself would not deny herself to me. My companion must be of the same species and have the same defects. This being you must create.

Frankenstein

Frankenstein was different because the story gave voice to the Othered. Until then, the monsters had been kept as Minotaur opponents, not afforded humanity or sympathetic thoughts of their own.

Note that ‘feminine Gothic’ doesn’t have to be written by women nor star female characters. A ‘feminine Gothic’ story is defined by a number of criteria. One feature is the presentation of ‘subjectivity as female’, and in its own way, monstrous.

Susanne Becker offers Margaret Atwood’s novel Lady Oracle as an excellent example of feminine Gothic because the main character ‘Joan foster continuously engages in a play with herself as Other’.

In children’s literature, Margaret Mahy’s The Tricksters may also fit the category of feminine Gothic.

Revelation & Gothic’s Relationship To Mystery

Revelation is the basis of much plotted fiction, especially any story containing a mystery—and that includes far more than detective or mystery fiction. Much gothic fiction is founded on a central mystery. When a story’s main dynamic is to have the protagonist find out something, or realize something that’s been true for some time, the story’s narrative drive comes from the finding out, not in the discovered fact itself. More similar to a ‘whydunnit’ mystery than a ‘whodunnit’, in other words.

Often the framework of this kind of mystery/revelation story will be very simple: a quest or journey which involves meeting people, getting into one situation after another, each demonstrating the story’s central theme but otherwise unrelated to the others, each supplying some new information on the story’s central mystery.

The Mad Woman In The Attic Trope

The Mad Woman In The Attic is now a trope, though this real life story flips it — a woman kept her husband in the attic and made him live like a bat.

Jane Eyre —Mr. Edward Rochester keeps his violently insane wife Bertha locked in the attic of Thornfield. All the while, Rochester is romancing Jane. The story is Jane’s gradual discovery of the unchanging but hidden state of things. Except for the secret — the mystery — the story would be quite static.

Likewise, Rebecca, whose plot is the disclosure of dead Rebecca’s real nature and how her widower, Maxim, actually felt toward her. Rebecca is a more modern Bluebeard story.

Several Shirley Jackson short stories, including “A Visit” and “The Good Wife”.

Stranger Things, the Netflix TV show, also features a ‘girl in the attic’ trope in Eleven. Stranger Things is indeed a gothic story:

One of the most interesting aspects of this show is how it’s reminiscent of gothic fiction. A lot of early gothic is set in some kind of remote past yet reflects contemporaneous issues. With Stranger Things we have a 21st century TV show set in the 80s, which I guess for young people is a remote past, but speaking to our contemporary moment. We are thus looking at Stranger Things not as an exercise in nostalgia, but as a text that speaks to current issues like surveillance culture and the modern family. In short, it is interesting how the show turns to the past to speak to the present.

interview with Dr Phillip Serrato

- Bluebeard — the ur-Castle story

- Kafka

- Gormenghast series — three novels by Mervyn Peake, originally published between 1946 and 1959. Follows the life of Titus Groan, left to fend for himself in a crumbling kingdom he will one day inherit. He is surrounded by bizarre family members. He survives his neglectful childhood, grows up, survives attempted murder. The ending is thought to be pretty poor. Peake never bothered finishing it himself — it’s supposedly finished off by his family, which explains a lot.

- Princess and the Goblin and The Princess and Curdie by George MacDonald — these stories influenced C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien

- The horror classic film Freaks

- The Castle of Otranto (1764) by Horace Walpole is probably the most famous example of pure gothic fiction. The combined elements of terror and medievalism set a precedent for an entirely new, thrilling genre. This story was already a pastiche and self-consciously parodic send-up of the genre that it itself established. “A lonely, self-divided hero [embarks] on an insane pursuit of the Absolute” (Thompson, 1974). “He persecutes the maiden-in-flight and is himself destroyed, rather than attaining his immoral aims” (Becker, 1988)

- The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) by Anne Radcliffe — a good example of a paranormal scheme against a helpless young woman. Bourgeois heroine Emily St. Aubert endures all kinds of struggles. She loses her father to supernatural experiences in an old castle. “The heroine’s pursuit of self-fulfilment through marriage is interrupted byt he vilain’s intervention, which — ironically — enables her to solve a mystery related to her mother and to position herself with a much stronger sense of — psychological, social, linguistic — identity before attaining her original goal.” (Becker, 1988). Jane Austen was influenced by this book. The heroine continuously disavows her own foolish predisposition towards superstition by projecting it onto her servant girl, Annette. Radcliffe defamliarised ‘woman’s place’ by turning the home into a castle.

- The Haunted Beach (1758-1800) by Mary Robinson — a tale of a murdered man and a ghostly crew.

- Zofloya (1806) by Charlotte Dacre — “Zofloya is all about the voluptuous and half-demonic Victoria and her dealings with the all-demonic Zofloya—the devil disguised as a handsome Moorish servant. Although Victoria is suitably punished for her transgressions at the end, Dacre revels in depicting female desire (for a man of colour no less—scandalous) and you can’t help wondering if she isn’t rather on the devil’s side” (Dr Sam Hirst). Some disability scholars see Dacre’s heroine Victoria as transgressive: Her monstrosity is not a disability but a ‘hyper-ability’ (Norma Aceves).

- Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen (1817) is a parody of The Mysteries of Udolpho, which was already in some ways a parody of the Gothic tradition. Jane Austen parodied the genre but also seemed to really enjoy reading it herself. She continued to read gothic romance for years, even after parodying it. Pastiche may be a better word than ‘parody’ because it simply utilised various tropes, plot points and motifs.

- The History of the Caliph Vathek (1786) by William Thomas Beckford

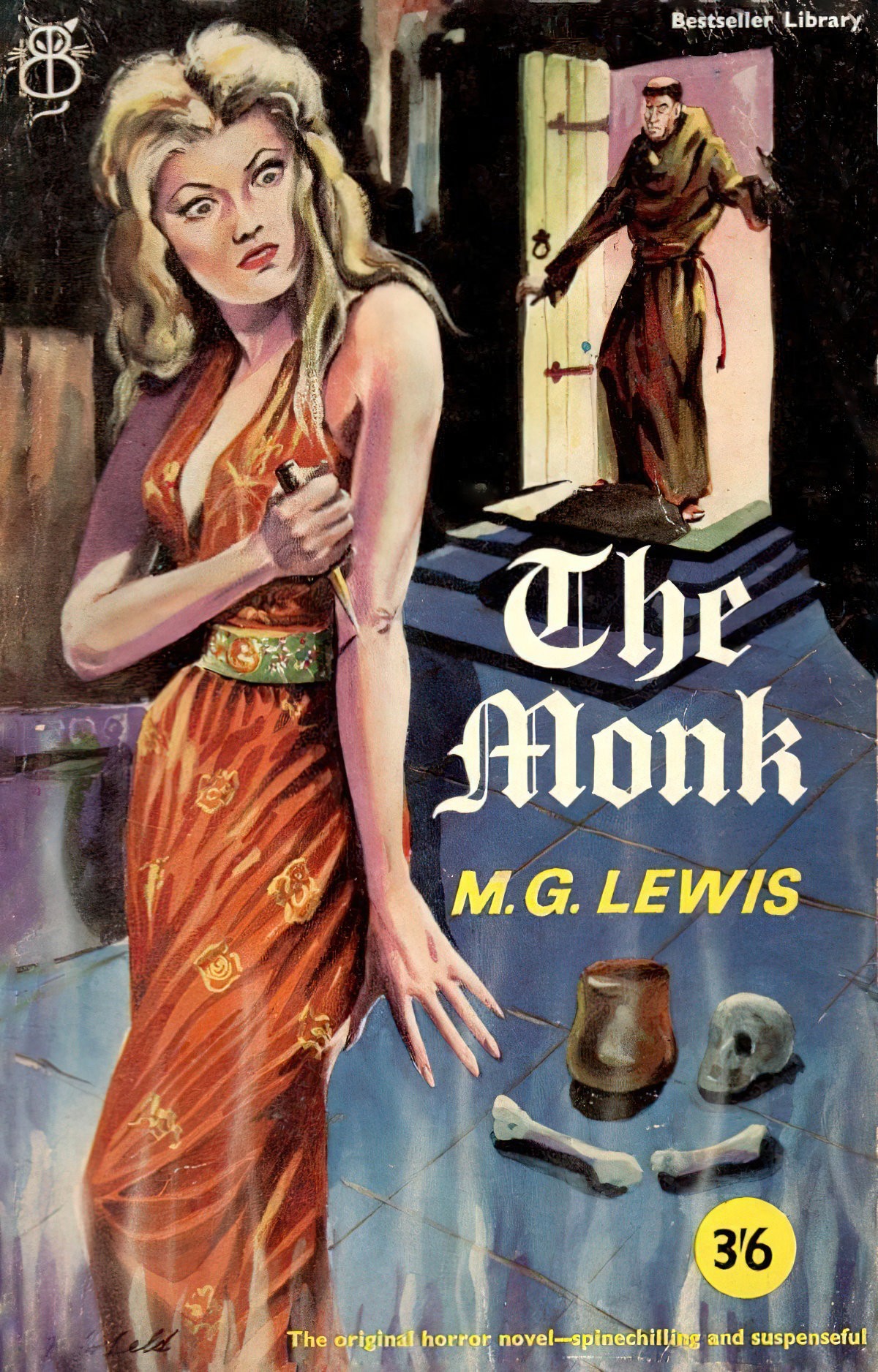

- The Monk (1796) by Mathew Lewis — Lewis was 19 when he wrote this novel of ecclesiastical debasement. It is stuffed full of love, murder and immorality, and scandalised England at the time.

- Frankenstein (1818) by Mary Shelley — This novel is the pinup Gothic novel. Dr Frankenstein creates a creature from body parts culled from graves at the local cemetery. It was Ellen Moers who first recognised Frankenstein as a birth myth in 1978, which started academics thinking harder about the role of mothers in Gothic fiction.

- Melmoth the Wanderer (1820) by Charles Maturin

- Salathiel the Immortal (1828) by George Croly

- The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831) by Victor Hugo

- Varney the Vampire; or, The Feast of Blood (1847) by James Malcolm Rymer

- The Fall of the House of Usher (1839) by Edgar Allan Poe

- Thérèse Raquin by Émile Zola — Thérèse and her lover, Laurent, are devoured by remorse after drowning her husband, Camille.

- The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886) by Robert Louis Stevenson

- Dracula (1897) by Bram Stoker — Vampires, haunted kingdoms, blood.

- Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë — Is Thornfield Hall haunted by a ghost? The ur-Madwoman in the Attic story.

- The Picture Of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde — a philosophical work about getting old and indulgence. The main character becomes so obsessed with stayng beautiful that he sells his soul. He occasionally goes up to the attic to watch his portrait grow old.

- The Woman In Black (1983) by Susan Hill — A best-seller from the 1980s. A spooky visitor haunts a small town in England, warning that children are going to die. It’s been adapted for stage and is a hit in West End. This one has a very strong sense of place, set on a foggy stretch on the English coast, dangerous marshland on a bit of land which gets cut off from the mainland at high tide.

- Interview With The Vampire by Anne Rice — Written as an interview between a reporter and a vampire called Louis de Pointe du Lac, who recounts the last 200 years of his life. He is full of regret.

- Work by Clive Barker has gothic elements

- Stephen King’s work is very clearly modern Gothic, but when asked, King says he can’t think of any academic subject more boring than trying to define what Gothic is and is not.

- The Tell Tale Heart (1843) by Edgar Allan Poe — the murderous main character is haunted by the sound of the beating heart of his victim, hidden in pieces under the floorboards.

- Wuthering Heights (1847) by Emily Bronte — Set on the moors, this story is about class, survival, prejudice and is highly atmospheric.

- The Tale Of Raw Head and Bloody Bones by Jack Wolf

- 10 Gothic historical stories and novels that interrogate history but aren’t subject to it

- Beloved by Toni Morrison — In the wake of the Civil War, former slave Sethe settles with her family in Cincinnati. When slave-catchers threaten to return the family to the Kentucky plantation they’ve only just escaped, Sethe drags her small children outside to the woodshed and tries to kill them. The ghost is a stand-in for the spectre of slavery.

- The Meaning Of Night by Michael Cox — Our narrator, Edward Glyver, picks an innocent man from the crowd, tracks him through the seamy backstreets of Victorian London, and stabs him to death. That’s just the opening.

- Dark Matter by Michelle Paver — This is neo-Gothic in that the scientific research station is a modern take on the Gothic haunted house. A guy called Jack is the main character. The ghost parts are a symbol of claustrophobic loneliness as the days on Svalbard get shorter and shorter.

- Bitter Orange by Claire Fuller — Set in 1969, a middle-aged narrator has been employed to stay at Lyntons in order to catalogue the gardens for its absent American owner. So far you might be thinking a little of The Remains of the Day. But in this one, Frances is joined by a young couple to whom she is attracted, and the supernatural elements stand-in for her disturbed mental state.

- The House On Vesper Sands by Paraic O’Donnell — London, 1893: high up in a house on a dark, snowy night, a lone seamstress stands by a window. So begins the swirling, serpentine world of Paraic O’Donnell’s Victorian-inspired mystery, the story of a city cloaked in shadow, but burning with questions: why does the seamstress jump from the window?

Gothic Children’s Literature

A Brief History Of Gothic Children’s Literature

Gothic children’s literature emerged in response to the adult Gothic romance. However, even children in the 18th century probably preferred the scary tales over the didactic ones they were supposed to read, which were heavily didactic. There was an effort by the gatekeepers of this time to keep Gothic stories away from children. This fear has never subsided. There are always cultural critics worried about the effect Gothic stories have on the tabula rasa of children. In earlier eras children were thought to be entirely innocent. Rousseau was partly responsible for that. These days stories tend to play with the idea that children are somewhat complicit in getting themselves into trouble. This is why children’s stories, too, quite often give a moral shortcoming to the main character. This affords children more agency, in fact.

Maryrose Wood uses this historical attitude in her gothic parody The Mysterious Howling when she writes:

[Penelope the governess] had chosen Dante because she found the rhyme scheme pleasingly jaunty, but she realised too late that the Inferno’s tale of sinners being cruelly punished in the afterlife was much too bloody and disturbing to be suitable for young minds. Penelope could tell this by the way the children hung on her every word and demanded “More, more!” each time she reached the end of a canto and tried to stop […]

Penelope had begun reading poetry to the children in the belief that it would improve their English faster than lists of spelling words ever could. Besides, she personally found poetry very interesting, and since her students [literally raised by wolves] were more or less blank slates when it came to literature, she felt she might as well do what she liked. (As you may already know, the Latin term for “blank slate” is tabula rasa, a phrase the Incorrigibles would no doubt be exposed to a little further on in their educations.)

The Mysterious Howling, book one of The Incorrigible Children Of Ashton Place

The influence of Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otranto is more commonly named as an influence, but Dante’s Inferno and Comedy are also known among scholars to have directly influenced several well-known Gothic texts, namely: Vathek by William Beckford (1786) and The Monk by Matthew Lewis (1796). The goriness and the dramatic finale are straight out of Dante.

Recently we have those fears directed towards the Twilight series, in which the passive heroine basically waits around to be saved by a creepy, much older male monster. The fear is that girls in real life will hope to emulate this as a script for their own romantic lives. (I admit, I have some sympathy for this view myself, if girls are reading dark, paranormal fiction widely but not critically. Then again, who’s to say they’re not critical of the very stories they enjoy?)

Children’s stories have always been gothic. In fact, gothic stories belonged to children all along. The Gothic romances for adults actually came out of fairytales told while these adult readers were still children.

There was a lot of playing with Gothic conventions in the latter half of the 19th century, especially by woman writers, who were presumably reading gothic romance/horror themselves for pleasure.

Another three 18th century woman writers started writing partly in order to combat what they considered worrying trends in contemporary children’s fiction. These women were Mary Wollstonecraft (Mary Shelley’s mother, 1759 – 1797), Anna Laetitia Barbauld and Maria Edgeworth.

Mary Wollstonecraft wrote a seminal feminist work called Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). But she also wrote Maria, of the Wrongs of Women (1798) in which men are the real threat, not the supernatural (much like a Scooby-Doo conclusion).

ABODES OF HORROR have frequently been described, and castles, filled with spectres and chimeras, conjured up by the magic spell of genius to harrow the soul, and absorb the wondering mind. But, formed of such stuff as dreams are made of, what were they to the mansion of despair, in one corner of which Maria sat, endeavouring to recall her scattered thoughts!

the opening to Maria, of the Wrongs of Women

Bear in mind that each of these women used Gothic features in their writing for children but it wasn’t actually Gothic because they didn’t want to expose children to ghosts. Also, each and every one of them wrote Gothic stories for adults in a different part of her writing career, exposing a double standard. We love the Gothic and find it entertaining, but not for children, whose minds are easily corrupted.

Influential male writers have said they loved to read Gothic chapbooks as children. These men include: Boswell, Johnson, Carlyle, Goethe, Lamb, Wordsworth and Coleridge. Yet chapbooks were never culturally approved.

WHAT ARE CHAPBOOKS?

Chapbooks (or bluebook pamphlets) were magazine type products sold door-to-door — an important means of cultural dissemination before people could afford books. Pioneered by Simon Fisher, a printer and circulating library owner, chapbooks were considered trash gothic fiction, not even gothic, but a corrupted form of what was already considered trash.

Chapbooks or pamphlets were a whole series of short tales, 36 to 72 pages long, distinguished by their flimsy blue covers, and thought to be redacted, plagiarized, abridged, extracted or imitations of popular novels and well-known gothic novels. But, of course, it would be erroneous to suppose that all chapbooks or bluebooks were merely diminutive renderings of gothic novels; in fact, very few were full abridgements of gothic or otherwise and some were indeed, original. Often illustrated with wood cuts or engravings, chapbooks were sold for under a Shilling and are now unmistakably linked to the vulgarization of the pastiche-ridden gothic, the dumbing down of the gothic’s intricate and convoluted plots, dark motifs and representations of the sublime, into simple tales of terror.

Franz Potter

Before the rise of the Gothic novel, faciliated by the development of cheap printing systems, the Chapbook and Bluebook were common forms of literature, particularly in the United Kingdom. For a penny or half-penny, members of the public of any class with the ability to read suddenly had access to a wealth of information (of varying degrees of accuracy) and stories of adventure and morality through these publications. Although looked down on by the higher classes of the time, and indeed by scholars of today, the Chapbooks and Bluebooks are a wonderful repository of folklore which can tell us much about the beliefs and traditions of the people of the time. In this edition of The Folklore Podcast, the first of Season 2, creator and host Mark Norman examines some of the folklore presented in the old Chapbooks and how it was used to teach lessons to others.

The Folklore Podcast

A very easy definition of Gothic children’s literature: Gothic stories are everything ‘quality’ children’s literature is not, in any given era. When a literature emerged for the middle class white child, ghosts were firmly erased.

Fear (or the pretence of fear) is very popular right now in children’s literature. This is the modern take on ‘gothic’.

Examples Of Early Gothic Children’s Literature

- Mary Louisa Molesworth (A Christmas Child, A Christmas Posy, An Enchanted Garden and so on)took the gothic tradition and domesticated it.

- A Sweet Girl Graduate by L.T. Meade is a vivid and detailed description of college life among a perfect bevy of young misses in the old English university town of Kingsdene. It follows the fortunes of a young Devonshire lass who goes away to college and finds herself among entirely different conditions of life and points of view than those that prevail in her own narrow village. L.T. Meade was perhaps the first to transform the school into a gothic place.

- The Secret Garden has the madwoman in the attic trope, though the prisoner is a little boy, not a mad-woman. There’s also the haunted house and grounds. The Secret Garden is the most obvious example of Gothic children’s literature.

- C.S. Lewis used The Woman In The Attic trope in his Narnia Chronicles — The Magician’s Nephew to be exact. The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe begins in a big old scary mansion and a scary, remote owner who is basically a hermit, probably with secrets of his own.

- The Gashlycrumb Tinies by Edward Gorey, who writes macabre rhymes. “A is for Amy who fell down the stairs, B is for Basil assaulted by bears…”In response to being called gothic, [Gorey] stated, “If you’re doing nonsense it has to be rather awful, because there’d be no point. I’m trying to think if there’s sunny nonsense. Sunny, funny nonsense for children—oh, how boring, boring, boring. As Schubert said, there is no happy music. And that’s true, there really isn’t. And there’s probably no happy nonsense, either.” — Wikipedia entry on Edward Gorey

- Emily series by L.M. Montgomery (who wrote Anne of Green Gables) — Montgomery plays with Gothic conventions, as well as in some of her stand-alone novels and short stories.

If you’re wondering about Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland, Alice is not Gothic literature. There are plenty of Gothic features without it adding up to actually Gothic. Alice is absurdist instead.

Features Of Gothic Children’s Literature

What does the Gothic look like in children’s literature? Gothic motifs in general are very well-suited to exploring adolescence, and the way identity seems to change from day to day. With the menarche, girls face blood — another Gothic motif (wayward fluids, murder). Elements include:

- Hobgoblins, dwarves, trolls, witches, werewolves, vampires and other folkloric creatures

- Bugaboos such as chimney sweeps, Wee Willy Winkies and other creatures from urban folklore. (Bugaboos come in the night.)

- Ghouls — The ghoul is the classic Gothic monster. They frighten us and transform the familiar into the strange and threatening.

- Ghosts, spectres, phantoms, apparitions and general hauntings

- Schools are often the proxy for haunted mansions and castles. The schoolyard is the forest.

- Irony and parody is very gothic, so anything meta in the style of Lemony Snicket borrows from the Gothic tradition. There’s a lot of parody of Victorian settings.

- The Gothic is to do with transgression, lack of restraint and the overturning of normality. For example, Gothic villains break taboos, as do young children, by not doing as they’re told. See again The Carnivalesque, which is a tradition with a long history in children’s literature. No wonder Gothic features so heavily in stories for the young.

- A lot of Gothic stories have a ‘jump’ ending. Take the oral versions of Little Red Riding Hood, for instance, in which the storyteller grabs the listener as if she is about to get eaten by the wolf. A number of modern stories for young children are also designed to be performed as much as read.

- The Gothic warns readers of the dangers mysteriously close to even the most familiar places. The Gothic tells us that the world is not safe. How many children’s stories teach that? Quite a number. Pretty much any story that’s not pastoral is teaching children that same lesson: Be vigilant, be smart, stick with your friends, know friends from enemies.

- Gothic children’s literature often takes the form of fantasy. If the Gothic is about fear of desire, fantasy is a great genre to explore that because fantasy teaches the reader to desire.

- Many children’s stories use the trope of the Explained Ghost. Basically, there’s some sort of supernatural happenings in the world of the story which is later revealed to have been just the over-workings of a foolish mind. This trope is used to teach the reader that there is no such thing as ghosts and whatnot, and to always dig deeper for the truth behind our fancies. Nevertheless, even the Explained Ghost tropes themselves rely upon Gothic motifs and traditions. That’s not to say traditional Gothic stories themselves didn’t make use of the Explained Ghost. Ann Radcliffe herself used it, though perhaps to a different end (to show up rational thinking by later subverting it).

- There are a lot of orphans in children’s literature. Absent maternity is a feature of the Gothic.

Tips For Writing Gothic Stories For Children

Unlike in Gothic romance for adults, child heroes are mostly given something to fight back with. They don’t wait around to be rescued, except in the odd parody. This is in line with the general advice when writing for children: heroes must be proactive and basically get themselves out of their own predicaments. They may ask for help from a mentor, but no one’s coming to save them.

The writer must be familiar with gothic motifs and tropes and settings — familiar enough to parody them, and to manage whether readers will find something scary or funny (or both).

Writers can take gothic motifs and transplant them to a new setting. This creates a kind of neo-Gothic (to borrow from the term neo-Western). For example, writers may take the labyrinthine qualities of a castle and reuse them in a dystopian city or in a setting inspired by cyberspace.

Gothic stories tend to do one of two things:

- They can either suggest subversive possibilities to readers

- They can scare children into submission and ensure conformity.

Be clear with yourself: Are you achieving the former? If not, you’re writing didactic, 19th century work.

Examples Of Modern Gothic Literature For Children

- Flowers In The Attic was the Twilight of my generation (teenagers of the 1990s). It features children locked in the attic of a big, mean castle of a house and a wicked grandmother. Also incest.

- Beautiful Creatures by Kami Garcia and Margaret Stohl — This is the first of The Caster Chronicles. It is young adult fiction about a main character called Ethan, who has lost his mother and feels trapped in a tiny town.

- Roald Dahl — Dahl’s work is popular partly because stories preserve the innocence of the child and retains the level of evil of the villain, but gives the child the means to save themselves. Daniel Handler has continued this tradition.

- Anything Gothic for children these days tends to be compared to Daniel Handler’s Lemony Snicket series, even if there’s not much else really in common.

- An example often compared to Lemony Snicket is The Incorrigible Children of Ashton Place, set in the mid 1850s.

- J.K. Rowling uses the madwoman in the attic trope in Harry Potter, more than once, and many other elements from Gothic fiction, being the master borrower and remixer of tropes.

- The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman — chronicles the life of Nobody Owens who lives in a graveyard. The story is a series of loosely connected stories about Bod’s life and what he learns about life/death.

- Coraline by Neil Gaiman is another middle grade novel from the gothic tradition, with its large house, bizarre characters and supernatural goings-on.

- Wolves In The Walls by Neil Gaiman is a picture book, with a title reminiscent of The Rats In The Walls, and is similarly gothic in tone.

- Leo: A Ghost Story by Mac Barnett and Christian Robinson — a picture book about a ghost called Leo who lives alone in a deserted house.

- The Dark by Lemony Snickett and Jon Klassen — a picture book set in a big, scary, empty, dark house. In reality the house is probably an ordinary one, replete with a mother/father, but the representation of the house on the page is how the boy feels about it.

- The Widow’s Broom by Chris Van Allsburg

- Ghostlight by Sonia Gensler — An American Gothic tale including an abandoned haunted mansion, spooky movies, imaginary games, film-making (a popular device in ghost stories).