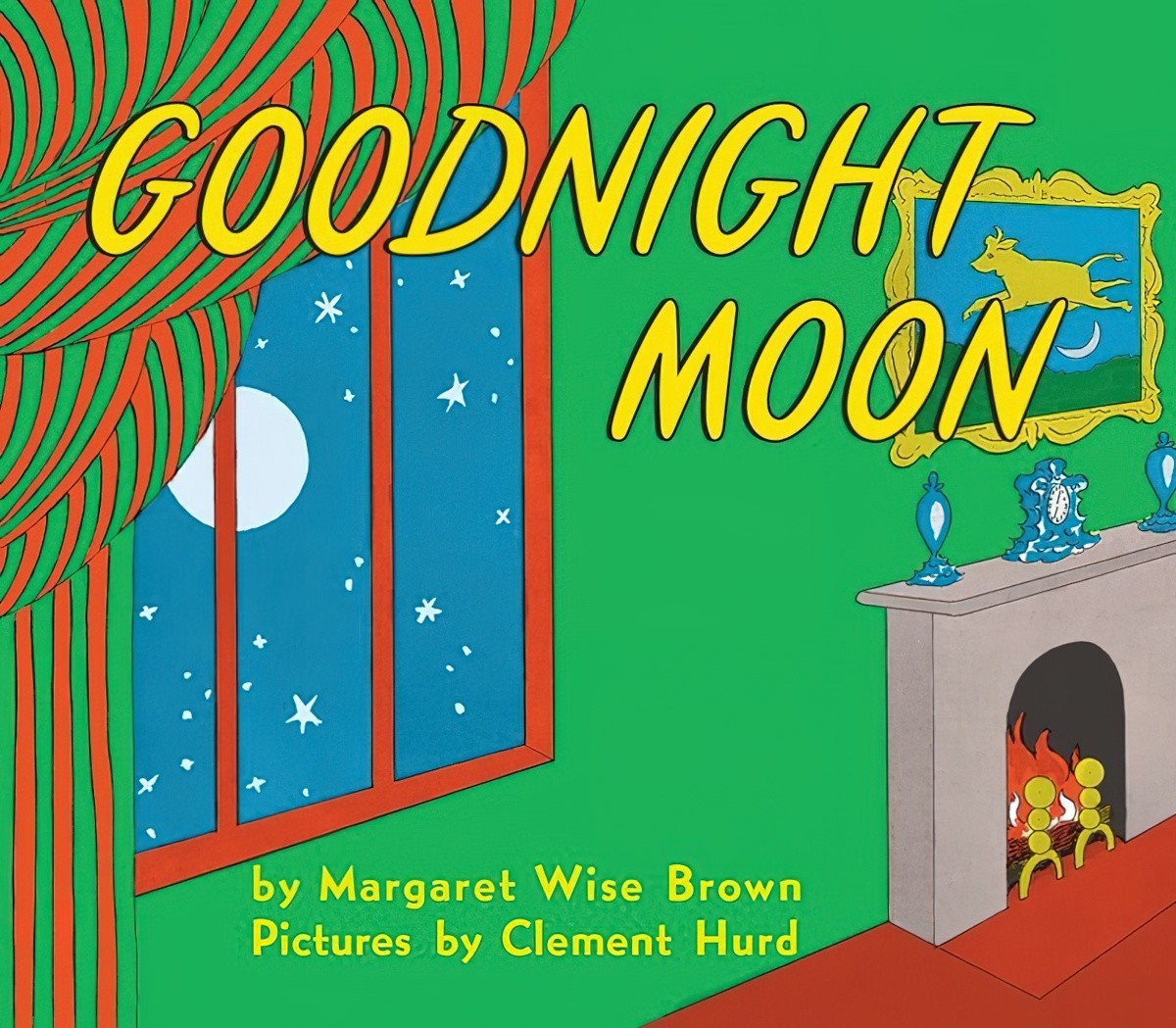

Goodnight Moon is an American picturebook classic, and is of particular interest because who would’ve thunk it? Margaret Wise Brown had a talent for creating odd-duck prose which went down a treat (and still does) with the preschool set. But is this book only of value for toddlers? Never.

PARATEXT

In a great green room, tucked away in bed, is a little bunny. “Goodnight room, goodnight moon.” And to all the familiar things in the softly lit room — to the picture of the three little bears sitting on chairs, to the clocks and his socks, to the mittens and the kittens, to everything one by one — the little bunny says goodnight.

In this classic of children’s literature, beloved by generations of readers and listeners, the quiet poetry of the words and the gentle, lulling illustrations combine to make a perfect book for the end of the day.

As the modern marketing copy says, Goodnight Moon is now a picture book classic. Margaret Wise Brown’s story is so popular, in fact, that it has made its way into popular culture. It’s assumed that Americans (at least) all know the original:

WHEN A STORYBOOK SETTING COMES ALIVE

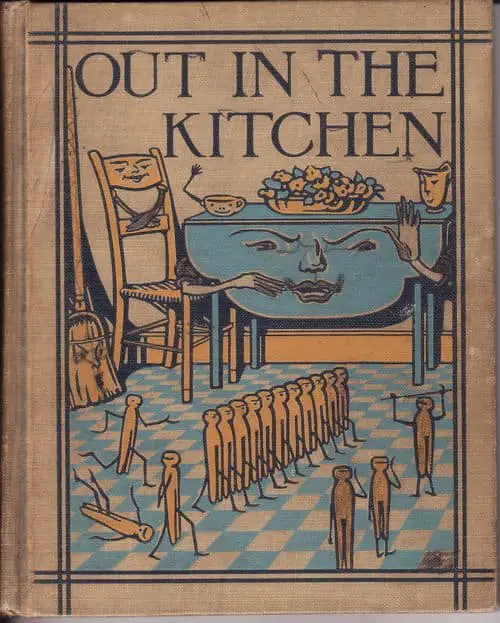

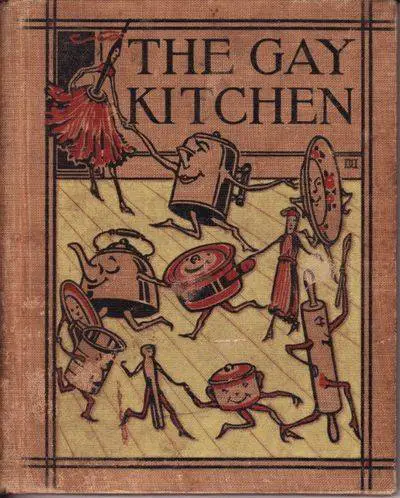

Humans seem to abhor a vacuum. We can’t bear the thought of loneliness. We fill nature with fairies, sprites and goblins. We fill space with little green men. We fill oceans with mermaids and sirens. Horror writers have even filled the hollows in our walls. For children we even animate the things around the house. In the kitchen, forks, spoons and chairs come alive. In Goodnight Moon every thing is alive; everything deserves a goodnight.

Wise Brown understood that children are inclined to see objects as characters within their own narrative, and respond especially well to stories in which toys/objects/trees come to life. In children’s drawings, as well as in illustrations for children, we see a lot of suns with faces, animals with eyebrows, houses that look like their windows are eyes, kindly looking cars and so on.

(Even for adults, cars have faces. And all the Jesus toast can testify to the fact that humans are inclined to see faces even where they’re not.)

Items which come alive were a popular subject for children’s books of the First Golden Age, but we can go back much, much further than children’s literature. Look at ancient religious beliefs, now called animism, where it was thought that things in nature are literally alive. It’s always been easy for humans to think that moving things are ‘alive’, but when the imagination keeps going — normally after dark — things get interesting.

THE DIVISIVENESS OF GOODNIGHT MOON

A negative view:

Name a canonical book you think is totally overrated.

No. Firstly because I never bad-mouth other writers, even if they’re dead, and secondly because I haven’t read enough of the Good Books to have an opinion. If I don’t like a book very much I’ll stop reading it.

Name a book you’ve read more than two times.

Fucking Goodnight Moon. Wait, actually, THERE’S a canonical book that’s over rated. It doesn’t even rhyme properly! It’s creepy! There’s an old woman watching over a terrified bunny while a bowl of mush cools on the bedside table. There are mice in the room and tiny socks! It’s like a movie by Guillermo Del Toro. Except, you know, less well art-directed. I hated reading that book, and yet I probably read it… [does math on her fingers, three kids, let’s say three times a week for five years each] 2,340 times. Shiver.

Flavorwire

A positive view:

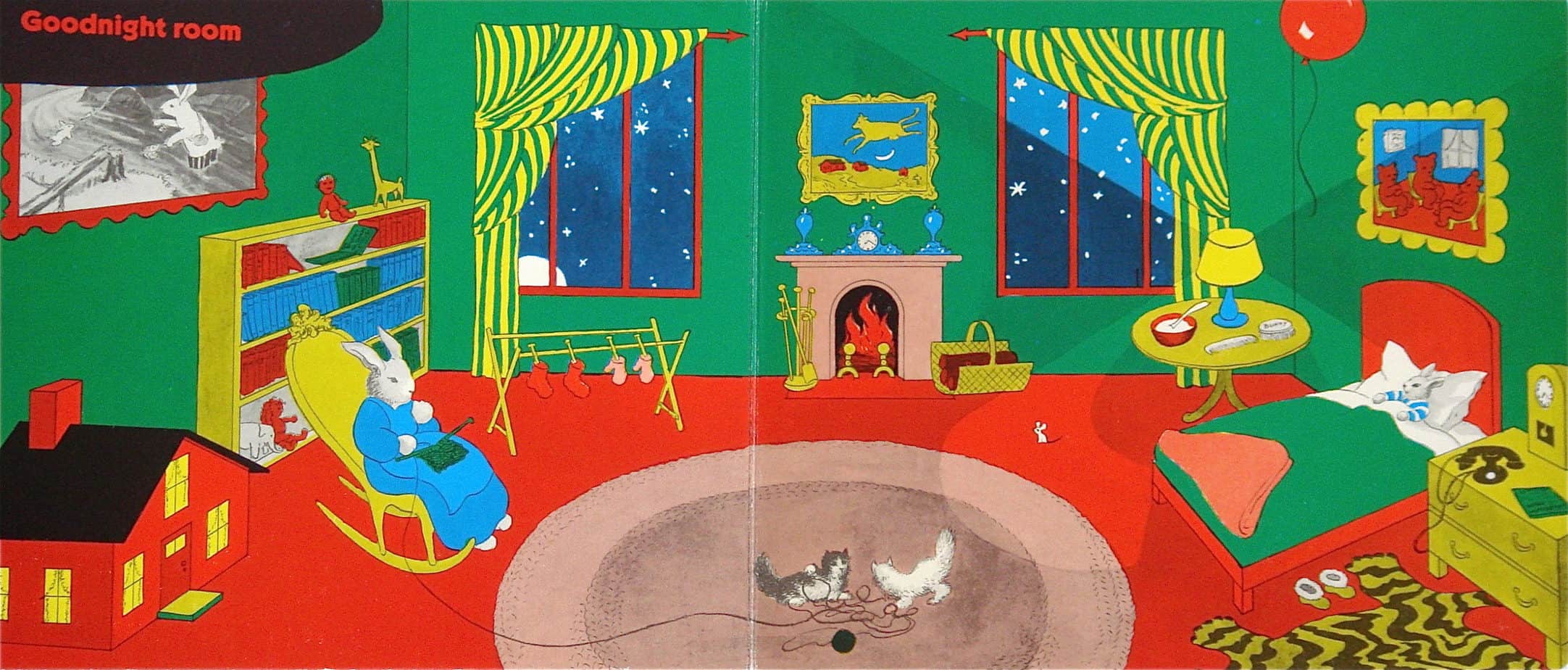

Many picture books — indeed, possibly all of the best ones — do not just reveal that pictures show us more than words can say; they achieve what Barthes called “unity on a higher level” by making the difference between words and pictures a significant source of pleasure. That pleasure is available even in a very simple book like Goodnight Moon. Margaret Wise Brown’s spare text is little more than a rhythmic catalog of objects, a list of details that encourages those who hear it to look for the objects mentioned in Clement Hurd’s pictures. In doing so, however, they learn information the text does not mention. The old lady and the child to whom she says goodnight are both rabbits and not people. The old lady is knitting, and the kittens play with her wool. The “little house” is a playhouse, and it has its own lights; knowledgeable viewers will even realize that the picture on the bedroom wall is actually an illustration from Brown and Hurd’s The Runaway Bunny. The delight viewers feel in discovering these things with their own eyes rather than with their ears reveals how basic and important is the difference between the information available in words and in pictures.

Perry Nodelman, Words About Pictures

STORY STRUCTURE OF GOODNIGHT MOON

Goodnight Moon is one of the most unusual, head-scratching stories I’ve ever analysed on this blog and I’ve come back to it several times. Most people describe it as a lullaby, which means it is exempt from universal story structure. It’s not a carnivalesque picture book, either (and those work differently again). After thinking about it hard, I believe Goodnight Moon is a more complete narrative than we give credit. Margaret Wise Brown was inclined to use symbolic scenes, only tangentially related to what we’d normally call a ‘big struggle’ or a ‘plan’. Be sure to compare this story to another of hers, Mister Dog, which I have also analysed. (In that story, Wise Brown lists things about Mister Dog for the reader as a proxy for the typical Anagnorisis.)

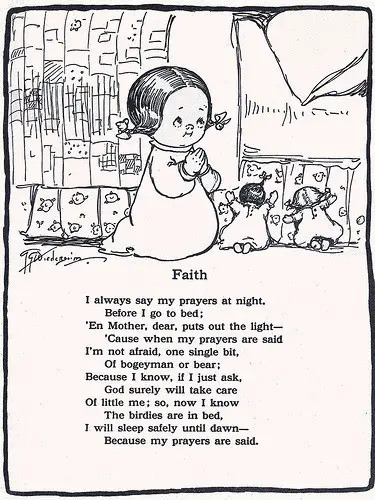

I conclude Goodnight Moon functions in the same way as a prayer before bed, warding off the bogeyman.

AN EVERY CHILD IS AT HOME

The child is in the body of a rabbit, which is one reason picture book creators like to make use of animals.

THE EVERY CHILD WISHES TO HAVE FUN

For this to work, the child starts in a place of boredom. ‘Boredom’ in this case means listing things about the room, starting with the greenness of the room, moving on to the telephone. The rabbit in this story is confined to bed by an adult presence who never leaves, so the rest of the story takes place entirely in the child’s head.

APPEARANCE OF AN OPPONENT/ALLY/PARTNER IN FUN

In a typical carnivalesque story, an outside fantasy creature would typically emerge. Here we simply have the child looking on as the kittens play with the mother rabbit’s wool.

FUN ENSUES

How much fun can you really have when you’re not allowed to get out of bed? Margaret Wise Brown is providing a model for the young reader. The picture of the cow jumping over the moon is a story within a story — a literary allusion. Young readers of the day would have been familiar with this nursery rhyme. The three little bears sitting on chairs is another illusion, to The Three Bears. The kittens and mittens remind me vaguely of Beatrix Potter. (One of Tom Kitten’s sisters is called Mittens.) The toy house calls to mind any story in which characters shrink or grow gigantic. The reader wonders at the juxtaposition of a comb, a brush, a bowl full of mush.

Most intriguingly of all, bunny says ‘goodnight nobody’. Ghosts? This is peak creepiness.

PEAK FUN

‘Fun’ is not the best word to use in this particular story, applying more to the fun kind of carnivalesque picture book. However, Margaret Wise Brown is clearly making use of The Overview Effect when she takes the reader outside the bedroom, saying goodnight to the stars and the air. The reader sees themselves as if from above, contextualised as a tiny creature within a much bigger universe. When combined with the doll house inside the room, this creates a beautiful mise en abyme effect, a form of spatial disorientation which in this case stands in for the ‘climax’ of the story.

RETURN TO THE SAFETY OF HOME

Although this ‘adventure’ has taken place only inside the bunny’s head, imaginatively bunny returns to bed, having lulled themselves to sleep.

The telephone is mentioned early in the book, but is absent from the litany of ‘Good night …’ salutations. Some have said that the primacy of the reference to the telephone indicates that the bunny is in their mother’s room and their mother’s bed. “Old lady” to me suggests grandmother. And why is there a doll house in the mother’s room? I don’t think Margaret Wise Brown gave any thought to verisimilitude when she created this bedroom. Instead, she included an admixture of items in which I imagine felt to her like an association game as she wrote it.

“Good Night Moon” was a favourite of mine as a little one and I looked forward to reading it with my daughter. Her response is interesting in view of this discussion about diversity. She was adopted into our family at 15 months and her response to the ending, where the quiet old lady whispering hush disappears was “where did the momma go?”

commenter from On Point

Where’s Wally Technique

Alongside all this, sleepy children look for the mouse in the picture, which forms a mini story in its own right.

RESONANCE

In Goodnight Moon, Wise Brown is basically teaching children how to lull themselves to sleep. It’s a variation of counting sheep, but with the interest of a story which very subtly builds and falls, in a symmetrical Freytag’s pyramid. The story structure itself is a calming shape. By seeing a bunny stay in bed, the bunny is modelling how not to untuck yourself, even if you don’t fall asleep immediately and get bored. The rabbit watching on functions as an omniscient presence as much as a reassuring one, reminding children that they are being watched.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION

Colour and Tone

The colour palette of Goodnight Moon is distinctive, with heavy use of green:

Perry Nodelman has this to say about the colour and tone of Goodnight Moon:

In Rosie’s Walk…there are large areas of pure color, all different from each other. The effect is slightly jarring but cheerfully exuberant. Books as different as Clement Hurd’s/Leo and Diane Dillon’s unrelated colors in shocking combinations, all share a quality of energy and excitement, whereas even pictures as vibrantly colorful as the scenes through the window in Keeping’s Intercity express bucolic serenity at least partly because of their careful blendings of different shades. … Pictures that use dark shades seem both more somber and more cozy than lighter pictures; consider the difference between the jazzy opening pages and the comforting closing ones of Clement Hurd’s Goodnight Moon, in which the gradually darkening room is evoked by a gradual darkening in the shades of the colors.

Words About Pictures

Interesting Censorship Decisions

In 2005, publisher HarperCollins digitally altered the photograph of illustrator Hurd, which had been on the book for at least twenty years, to remove a cigarette. (For more on Tobacco in Picturebooks, see here.)

Goodnight Moon contains a number of references to The Runaway Bunny. For example, the painting hanging over the fireplace of “The Cow Jumping Over the Moon” first appeared in The Runaway Bunny. However, when reprinted in Goodnight Moon, the udder “for caution’s sake was reduced to an anatomical blur” to avoid the controversy that E.B. White’s Stuart Little had undergone when published in 1945 (Making of Goodnight Moon, 21). The other painting in the room, which is never explicitly mentioned in the text, portrays a bunny fly-fishing for another bunny, using a carrot as bait. This picture is also a reference to The Runaway Bunny. The top shelf of the bookshelf holds an open copy of The Runaway Bunny, and there is a copy of Goodnight Moon on the nightstand.

Wikipedia

STORY SPECS

First published September 3, 1947

Anne Carroll Moore, the head of the Children’s Division of the New York Public Library … strongly believed that children needed fantasy and fairy tales, not stories about cars and busy city streets. The animosity between Moore and Mitchell was so strong that even Goodnight Moon, perhaps the best-selling children’s book of the Twentieth Century, and one that exemplified the tenets of the Bank Street School of storytelling, was not carried by NYPL branches until 1973.

Unbound

Goodnight Moon slowly became a bestseller. Annual sales grew from about 1,500 copies in 1953 to 20,000 in 1970; and by 1990, the total number of copies sold was more than 4 million.

The book has been translated into French, Spanish, Dutch, Chinese, Japanese, Catalan, Hebrew, Brazilian Portuguese, Russian, Swedish, Korean, and Hmong.

These days, Goodnight Moon is available as an app, in which the reader can magnify parts of the illustration.

FURTHER READING

Bright Kids Books have compiled a list of books similar to Goodnight Moon.

What Writers Can Learn From Goodnight Moon

The Golden Bunny by Margaret Wise Brown at About

Here is a nice profile of one of the illustrators of Margaret Wise Brown’s work — a woman who died recently and who should be more widely known. Her name is Dahlov Ipcar.

Sparknotes: Goodnight Moon is a McSweeneys spoof.

Goodnight Nobody is a podcast from 99% Invisible about how a children’s librarian disliked Goodnight Moon so much that no New York Public library carried Goodnight Moon until the 1970s.

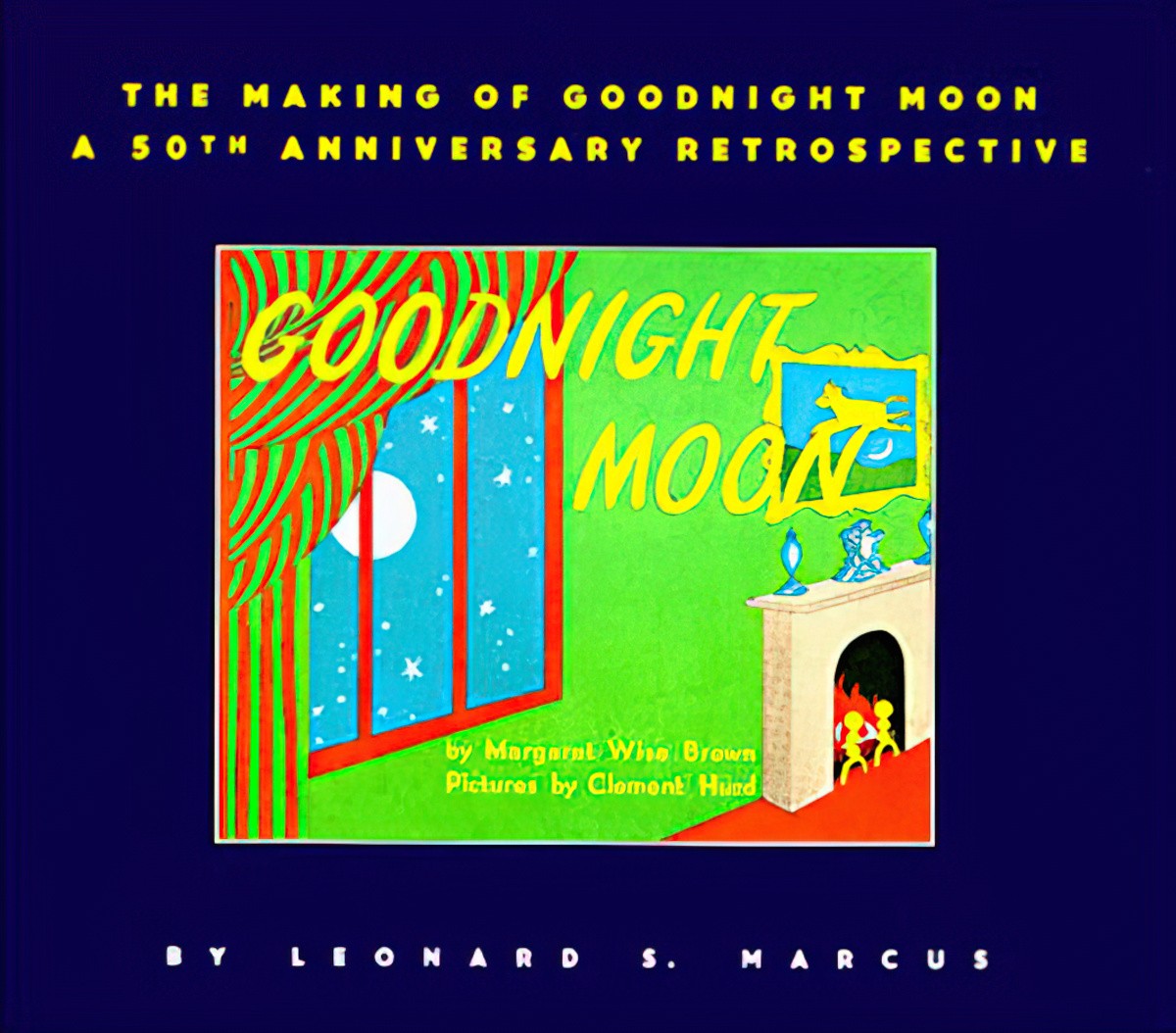

Leonard Marcus has written a book about the making of Goodnight Moon.

WRITE YOUR OWN

Author Susan Cooper writes that the book is possibly the only “realistic story” to gain the universal affection of a fairy-tale, although she also noted that it is actually a “deceptively simple ritual” rather than a story.

Going with Cooper’s description of ‘ritual’ rather than ‘story’, what other rituals exist which could be made into a ‘deceptively simple’ picture book?

- For older children?

- From other cultures?

- For adults?

- For rituals that don’t really exist, but might?

A pioneer of the 20th-century picture book, Margaret Wise Brown was born on May 23, 1910 in Brooklyn, New York.

Brown was a shy and thoughtful child with a love of animals that would later shine through her work. She attended Hollins University in Virginia before returning to New York to work at The Bureau of Educational Experiments, what is now the Bank Street College of Education. She then began work as an editor and was encouraged to write her own children’s books.

By 1941, Brown was a successful, full-time writer. She went on to write over 100 books for young readers, including beloved titles such as Goodnight Moon and The Runaway Bunny. Her quiet and poetic style continues to inspire today’s readers and children’s book creators.

Children’s Book Council

Brown loved the hustle and bustle of city life, but the short stories she wrote for adults failed to interest publishers. Feeling pressure from her father to either marry or start supporting herself, she eventually decided to enroll at the Bureau of Educational Experiments’ Cooperative School for Student Teachers—more usually known as Bank Street, for its Greenwich Village location. There, the school’s founder Lucy Sprague Mitchell recruited her to collaborate on a series of textbooks in a style Mitchell called “Here-and-Now.”

At the time, children’s literature still consisted largely of fairy tales and fables. Sprague, basing her ideas on the relatively new science of psychology and on observations of how children themselves told stories, believed that preschoolers were primarily interested in their own small worlds, and that fantasy actually confused and alienated them. “It is only the blind eye of the adult that finds the familiar uninteresting,” Mitchell wrote. “The attempt to amuse children by presenting them with the strange, the bizarre, the unreal, is the unhappy result of this adult blindness.”

Under Sprague’s mentorship, Brown wrote about the familiar—animals, vehicles, bedtime rituals, the sounds of city and country—testing her stories on classrooms of young children. It was important not to talk down to them, she realized, and yet still to speak to them in their own language. That would mean summoning her own keen, childlike senses to observe the world as a child does—which is how one chilly November she found herself spending the night in a friend’s barn, listening to the rumbling of cows’ bellies and the purring of farm cats.

The Surprising Ingenuity Behind Goodnight Moon

The following art has a similar palette to Goodnight Moon.