“The Erl-King” is a short story by Angela Carter based on an old ballad by Goethe, one of the most famous ballads ever told. Carter’s re-visioning doesn’t use the plot from Goethe’s ballad, but borrows some of the atmosphere. Carter inverts the gaze and turns it into something new. As you might expect from Angela Carter, her re-visioning expands notions of gender.

Below I take a look at both, as a compare and contrast exercise.

GOETHE’S ERL-KING

This classic ballad can be found easily online.

WHERE TO LISTEN

You may be able to unearth the BBC dramatization of this short story somewhere e.g. on YouTube. “The Erl-king” was broadcast 10 January 2000.

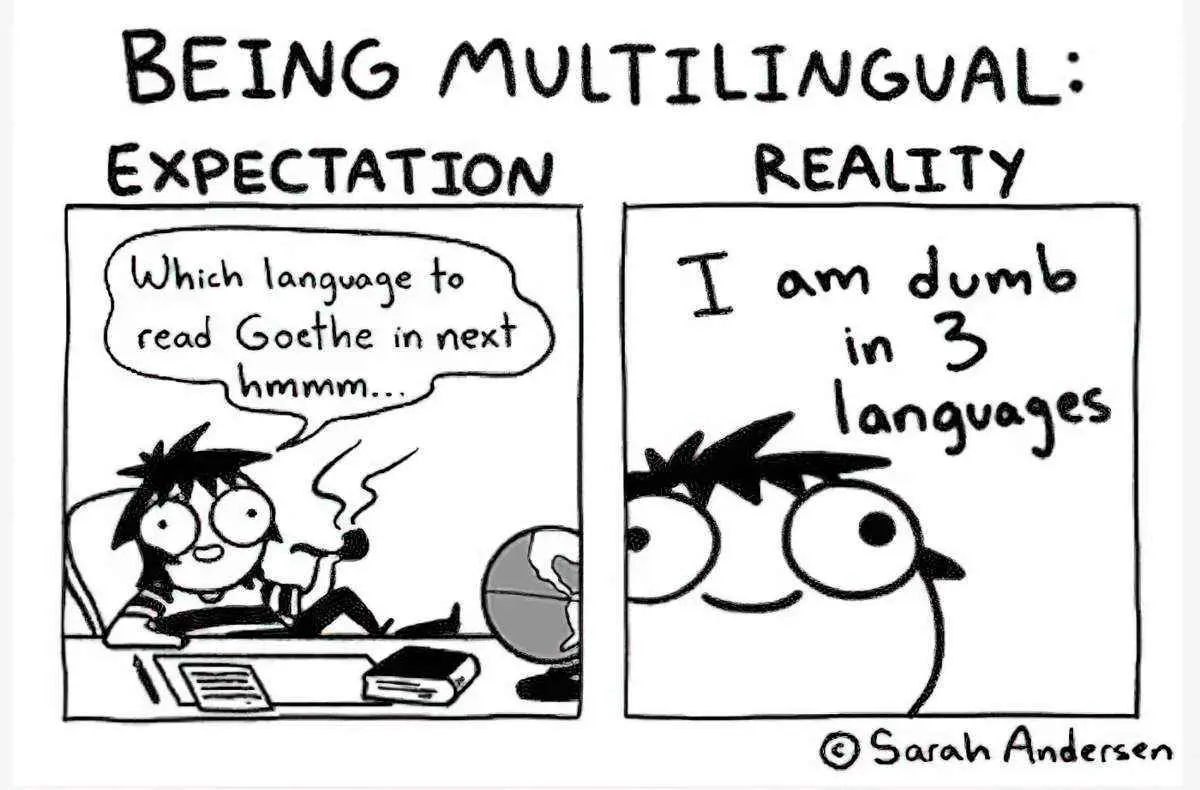

Goethe’s Erl-King (“Der Erlkönig”) is a terrifying narrative poem written by a German called Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in 1782. The Erl-King was originally composed by Goethe as part of a 1782 Singspiel (light opera) called Die Fischerin.

What Happens In “Der Erlkönig”

- A boy and his father are out riding one windy night.

- The boy is safe and secure, wrapped warmly in his father’s arms.

- Suddenly the boy hides his face.

- The boy has seen the Erl-King, or fairy king, who he recognises by the Erl-King’s cloak and crown. The Erl-king is King of the Elves and is hideous.

- The father reassures the boy, telling him there’s nothing around them but mist. Perhaps he even persuades himself there’s nothing there. The father’s shortcoming is that he has learned not to trust his senses. He is probably doing that very adult and logical thing by relying on past experience, in which he thinks he sees some terrible creature out of the corner of his eye but it always turns out to be nothing.

Who’s riding so late, in the night and wind?

It is the father with his child.

He grasps the boy in his arm.

He holds him securely; he keeps him warm.My son, why do you hide your face so fearfully?

“Father, don’t you see the Erl-King there?

The Erl-King with his crown and train?”

My son, it’s a streak of mist.

- But the Erl-King starts to sing right into the little boy’s ear, asking the boy to come with him. He promises to play games and find bright flowers together on the shore. We never learn why the Erl-King wants the boy. As in Rumpelstiltskin, we just assume that everyone wants children, especially boy children, fantasy creatures included.

- Only the boy can hear the Erl-King speak. The father insists there’s no sound but dry leaves in the wind.

- The Erl-King keeps promising things to the boy — daughters who will dance for him all night, holding him and rocking him and loving him. (There are real-world religions which promise feminine care and sex to male followers in the after life.)

- Now the Erl-King’s daughters beckon to the boy.

- The father doesn’t see (or acknowledge) these supernatural creatures and insists the beckoning girls are nothing but willows.

- The Erl-King becomes desperate for the boy and says if he won’t come willingly, he’ll take him anyway.

- The boy tells his father the Erl-King is gripping him.

- Finally the father believes the son. (It’s not clear why he suddenly believes the boy now. Why not before?)

- The father quickly dashes home with his son in his arms.

- But when the father reaches home, he discovers his son is dead in his arms.

RESONANCE OF GOETHE’S BALLAD

The trope of the adult who lies to children hoping to protect them is utilised frequently in stories. This variety of adult dishonesty continues to be punished in the majority of narratives, if only because the child is proven correct about The Scary Thing, exposing the adult as a fool and a liar.

[Goethe’s] ‘Erlking’ … personifies death as a danger above all to the young, who are credited with a more intense perception of the other world in the first place; this intimacy with the supernatural makes them vulnerable to its charms and its desires. Fear is the child’s bedfellow.

Marina Warner, No Go The Bogeyman

Goethe’s ballad has been set to music by several composers, most notably by Franz Schubert.

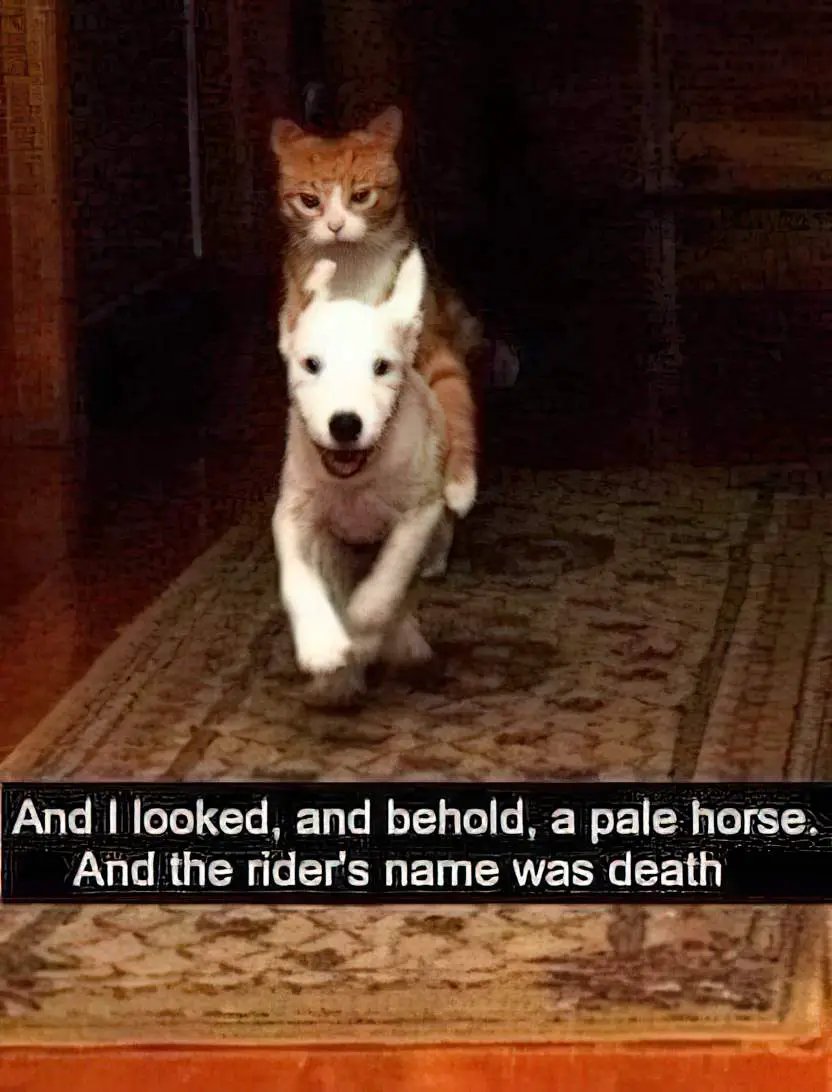

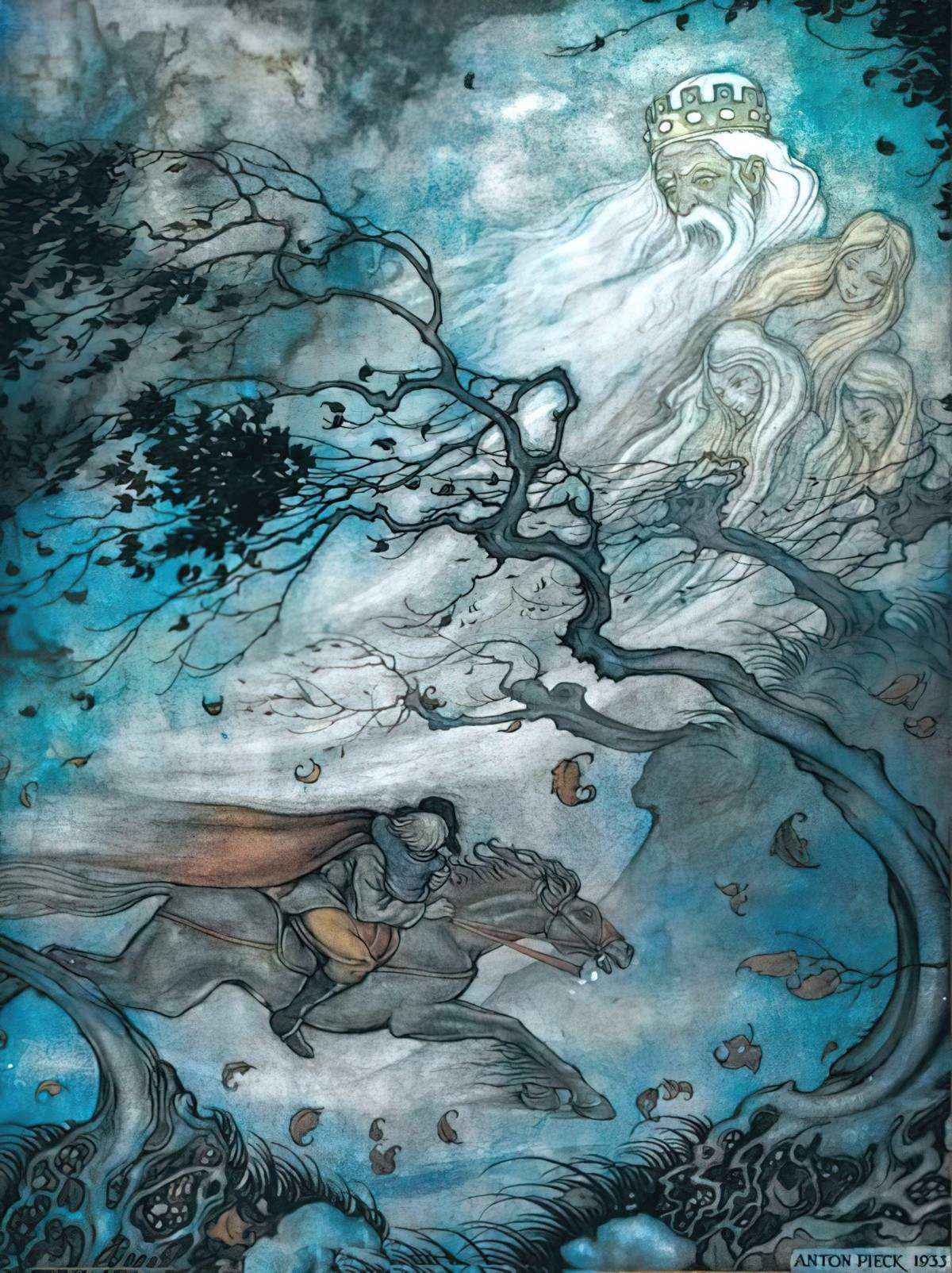

Many artists have illustrated Goethe’s “Erl-King”. The etching below evinces an unmistakably scary, Gothic tone.

But other artists, long before Angela Carter got to it, saw the erotic potential in Goethe’s ballad. The natural target for this objectification was not The Erl-King himself, because these classic artists were largely heterosexual men, but the Erl-King’s daughters.

ANGELA CARTER’S RE-VISIONING

Once Angela Carter gets hold of the Erl-King story, she removes the daughters and instead sexually objectifies the Erl-King, handing the gaze to our narrator. (She also inverts the gender of the male gaze with various other tales in her Bloody Chamber collection.)

Angela Carter’s Erl-King is a masterpiece of liminality and spatial horror, a.k.a. disorientation.

PARATEXT OF “THE ERL-KING” BY ANGELA CARTER

Most readers coming to Carter’s short story will be at least somewhat familiar with Goethe’s original, though it stands alone. This is a prospective retelling, though familiarity with Goethe’s ballad illuminates Carter’s feminist take.

I came to Carter’s “Erl-King” expecting she’d do more with the misty, windy environment, but she does much more with the autumn leaves. I thought there’d be a horse but there isn’t. Familiar with many of Carter’s other works, I thought the story might be about the Erl-King’s daughters, but again my expectations were wrong.

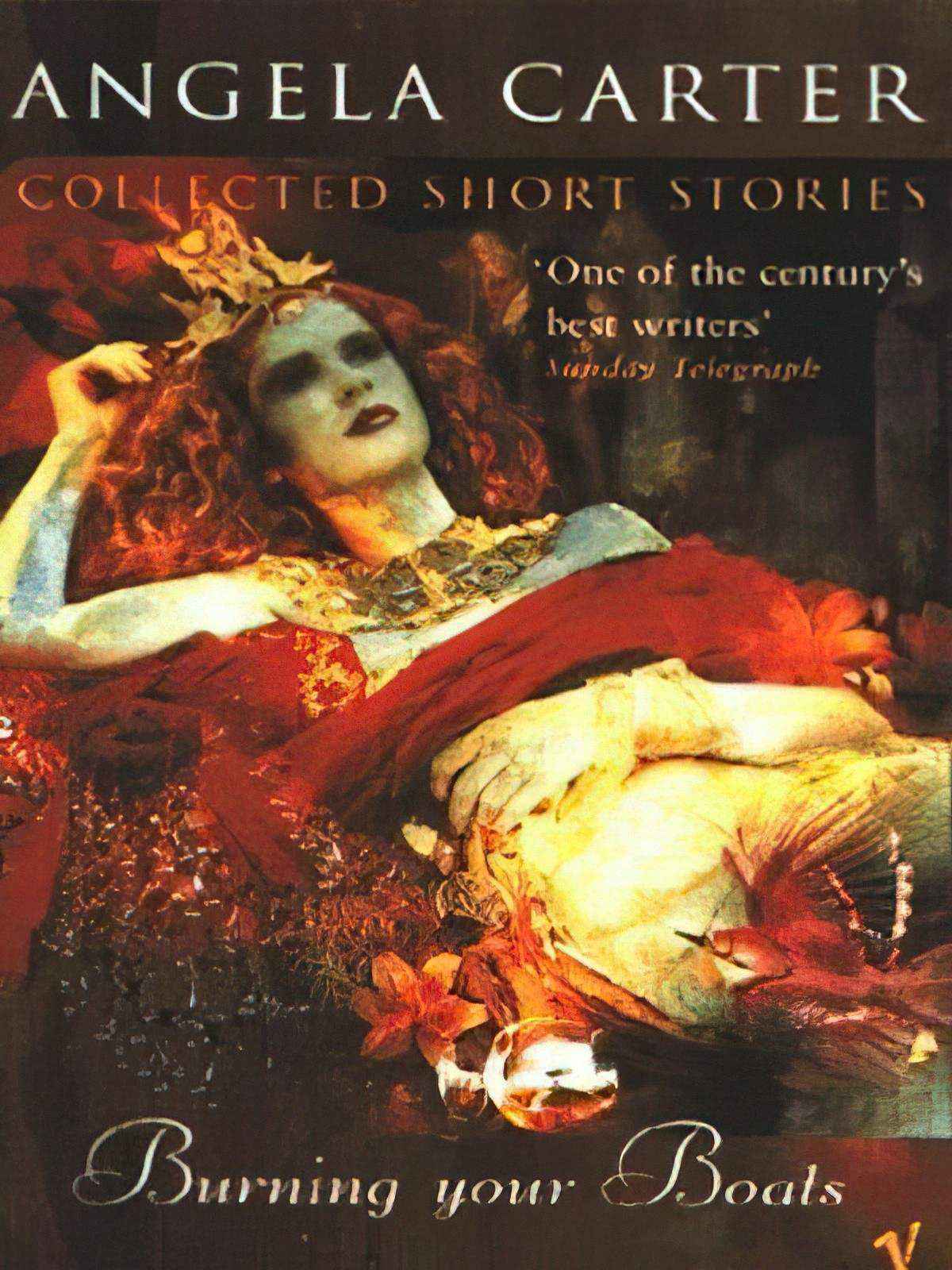

I own an out-of-print copy of the collected short stories of Angela Carter and I think the image on this 1996 cover might depict “The Erl-King”. The character manifests a 1990s version of femme-androgyny. They are crowned like royalty. There’s a forest in the background, and the character becomes one with the dropped foliage in the foreground. This character is part human, part forest; betwixt female and male; neither real nor unreal (like any fear); both powerful and vulnerably lying back; unmistakably inviting our gaze.

CARTER’S TREATMENT OF TIME

Carter’s re-visioning takes place in a fairytale world, with a symbolic forest both protective and scary, and in a place which runs on mythic time (kairos) rather than linear time (chronos).

THE SYMBOLISM OF SEASONS

Unlike classic fairytales, Carter does give us some specificity with the time. The story opens with a rainy day in late October. This accounts for the crunchy leaves of Goethe’s ballad, of course. “Withered blackberries withered like their own dour spooks”. Blackberries are paradoxically symbolic, being both delicious and a pest of a plant, covered in thorns. Here they indicate that summer was a forest cornucopia, but now — in another example of liminality — summer is turning into winter. (The in-between seasons have liminal potential.)

Carter personifies the autumnal light (striking the wood ‘with nicotine-stained fingers); winter is subsequently personified (it ‘grips hold of your belly and holds it tight’). The little stream has ‘grown sullen’, the trees make sounds like the taffeta skirts of women lost in the woods, and so on. This is a story in which the setting is a character in its own right. Carter takes this storytelling technique to its extreme, because The Erl-King equals the forest.

CHRONOS AND KAIROS

But when does this story take place, exactly? It works on ancient, fairytale time, which turns back on itself, repeats with each season (the underlying reason why Carter mentions season), and note that Carter places us firmly in a particular season, ‘grass grew over the tracks years ago’, which reminds me of the timelessness of fantasy worlds such as Narnia. Clearly, time works differently through the gates of this forest portal: because ‘once you are inside [the wood] you must stay there until it lets you out’. Apart from ‘autumn’, there is no specificity of time in these details.

Also, the story begins in present tense and later switches to past tense, which is another way of making the switch from iterative (kairos) to singulative (chronos). (It’s done a bit differently in most children’s stories.) Kairos is all about the time of antiquity whereas chronos describes modern, linear time. Kairos is sometimes switched out for the phrase ‘mythic time’.

NARRATION

Notice the story opens with second-person narration, unusual outside the genre of pick-a-path adventures. In general, audiences don’t have much patience for lengthy passages of second person narration. Carter doesn’t stick with it for long — just long enough to make us feel as if we are the main characters of our own story. This forest is the subconscious, and every single one of us has one of those — this story is about all of us, and about no one in particular.

The second person narration ends at mention of Little Red Riding Hood, which reminds us that this is a fairytale world. “She will be trapped in her own illusion because everything in the wood is exactly as it seems.” This is the perfect metaphor for the deep, dark subconscious; though the veridical world is nothing like our dreams, our dreams are nonetheless real to us, because we experience them as real while asleep; our fears and desires guide our actions in a very real way.

Little Red Riding Hood turns into a ‘character’ called ‘the interloper’.

Then the unseen character becomes ‘I’ before switching back to ‘you’: ‘Erl-King will do you grievous harm’, but this time the second person address is clearly ‘universal you’, something dished out as eternal advice.

SPATIAL HORROR OF CARTER’S “ERL-KING”

Writers use a variety of tricks to discomfit the reader and Angela Carter has a massive toolbox. Her stories are full of spatial horror. She is constantly working to disorient. So, what’s in her toolbox?

MISE EN ABYME

Carter uses mise en abyme in “Peter and the Wolf”. She uses it here too when describing how the woods ‘enclose and then enclose again’. This mise en abyme effect is repeated in Carter’s description of the stripping of the heroine, who has several layers; first her clothes, then another layer, her ‘last nakedness, that underskin of mauve, pearlised satin, like a skinned rabbit’. Then the mise en abyme reverses as the Erl-King dresses her again.

MORPHING PERSPECTIVE

the intimate perspectives of the wood changed endlessly around the interloper, the imaginary traveler walking toward an invented distance

There’s something very Escher about that.

VERTIGO

I am not afraid of him; only, afraid of vertigo, of the vertigo with which he seizes me. Afraid of falling down.

CLAUSTROPHOBIA

Falling as a bird would fall thorugh the air if the Erl-King tied up the winds in his handkerchief and knotted the ends together so they could not get out.

WHIRLPOOL EFFECT

The equinotical gales seize the bare elms and make them whizz and whirl like dervishes

THE FOREST SETTING AND ITS CONNECTION TO THE REAL WORLD

“The Erl-King” is basically an evocation of setting, but this is no ordinary forest: This is a forest of the imagination, and an allegory for how it feels to be a woman straddling that impossible dichotomy between ‘virgin’ vs ‘whore’. That’s the well-known feminist reading.

LIMINALITY AND GENDER

Carter’s Erl-King transgresses gender lines:

He goes out i the morning to gather his unnatural treasres, he handles them as delicately as he does pigeon’s eggs

He makes salads

He is an excellent housewife.

Carter wrote “The Erl-King” over 40 years ago in the midst of second wave activism. Fast forward to 2020 and I propose the virgin-whore dichotomy has lessened a little for women, at least in some cultures and subcultures.

But there are many outworkings of liminality. These days the word ‘intersectionality’ is widely known. ‘Liminal’ in allegory might equal ‘intersectionality’ when applied to social justice activism. Carter’s liminal, feminist, gender expansive “Erl-King” remains relevant as ever.

THE GENDER OF THE NARRATOR

The Erl-King’s gender is unimportant to the narrator. Commentators generally assume the narrator is female. For example, Marina Warner calls our narrator-guide ‘the heroine’, because she embodies femme-coded characteristics. This is a fair conclusion because The Erl-King is clearly a critique of prison-like matrimony. Doves settle on the Erl-King and those rings around their necks are ‘wedding rings’.

There are other intertextual clues that tell us the narrator is female. The Erl-King keeps other femme-coded characters in cages and captures this narrator. We traditionally associate birds and cages with femme-coded characters, no doubt about that. (And no story stands in isolation from its cultural context, etcetera.)

WOMEN AND BIRDS

I suspect Angela Carter was very familiar with the trope of women compared to birds (and also cats). If you spend half a day looking through classic art from Europe it really stands out — young women and girls with birds, birdcages, birds all around them. In literature, women are often compared to birds via metaphor and simile.

This is two-fold: A human being with an affinity for birds embodies appropriately gentle feminine attributes. Also, birds are small and vulnerable, much like women-and-children (I mindfully hyphenate that phrase).

But what if the story is more gender expansive than that? If The Erl-King transgresses gender roles, might our narrator be of any gender when re-read in the age of marriage equality?

THE CASE FOR A GENDER EXPANSIVE MAIN CHARACTER

Okay forget the here and now, let’s briefly revisit Ancient Rome, when sexual identity was not contingent upon a person’s attraction to a particular gender/s, but instead on how much ‘control’ people were able to exert over their impulses (sexual, economic and so on).

Our modern focus on gender as a main determinant of our orientation and identity is very recent in the history of humankind. (Michel Foucault went deep into this.) But what if we instead divided people into ‘those turned on by satin sheets’ or ‘my orientation is feather boas’ or whatever? What might we call someone turned on by their awe of personified nature? The narrator in this story is clearly aroused by the forest, which they regard as alive, personified throughout the entire story, evinced by Carter’s choice of imagery. Might attraction to ‘the power of nature’ not just as easily function as an orientation in its own right? And if you are part human, part forest, do you even have a gender? Reading this story in 2020 makes me want to throw the boundaries of gender identity and sexual orientation out the window.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE ERL-KING”

Although Carter’s “Erl-King” is a lyrical exploration of setting and character (one and the same in this case), does it have a structure to speak of? First requirement: a character shortcoming.

SHORTCOMING

Before looking into any moral or psychological shortcomings we need a main character. This is an example of a story in which a viewpoint character (the narrator) looks on and describes another character in great detail, in which case the very concept of ‘main character’ becomes moot.

Warner describes the narrator’s main shortcoming thusly:

Like Goethe’s poems, Carter angles the terror through the fascinated eyes of the Wellings prey. The heroine is in thrall despite herself to the woodland spirit’s feral, eldritch [sinister or ghostly] charms.

Marina Warner

So let’s call her ‘the heroine’. We might also call her the ‘victim muse’, a Gothic archetype of the Romantic era.

[A]nxiety about sexuality and the imagery of engulfment are also combined in [The Bloody Chamber]. This is particularly visible in “The Erl-King” … In the story, the protagonist dwells on her attraction to a fae figured called the Erl-King. The Erl-King captures women who stray into the woods and transforms them into birds that he keeps in cages. Despite this danger, the protagonist allows him to seduce her.

Alex Rouch at BookRiot

In “The Erl-King”, Angela Carter creates a man who literally transforms a woman into a bird, but this is allegory for how men typically consider women: As both gentle and vulnerable.

Is this heroine both gentle and vulnerable? I argue no, not until The Erl-King turns her into a bird and puts her inside that cage. She is brave. You have to be brave (or stupid, I guess) to enter a creepy forest all the while knowing you might not come out alive.

She is also fully in touch with her erotic side, slightly wild. He tames her via the metaphorical equivalent of marriage.

DESIRE

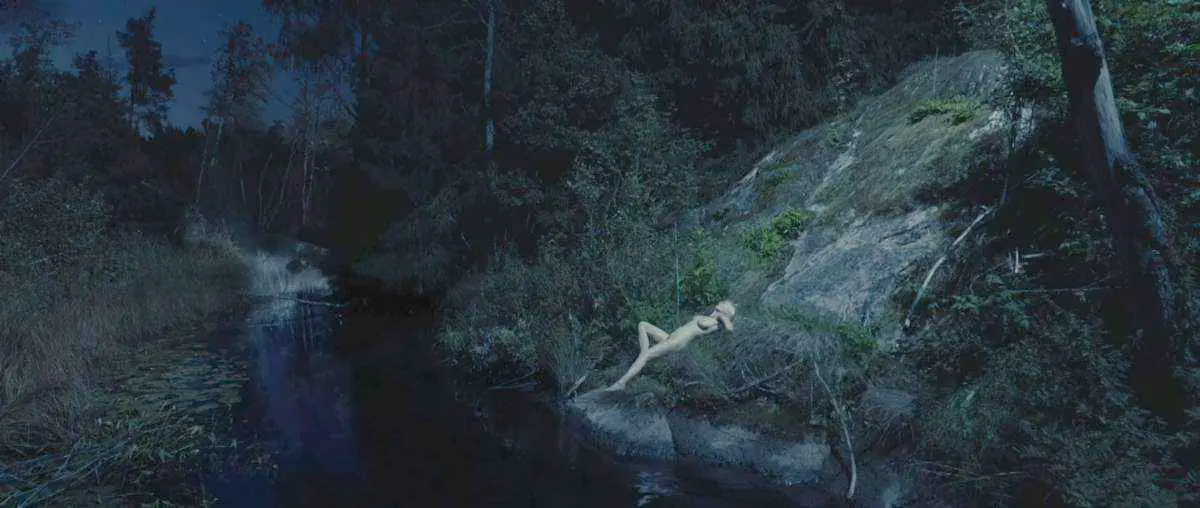

So at the start of the story, the heroine/victim muse is basically horny, driven by a baser instinct. The forest is so overwhelming that she is sexually in awe of it. ‘Nature’ is her orientation. I’m reminded of a scene from Melancholia.

‘Desire’ in Carter’s “Erl-king” is both narrative and sexual. Apart from communing with nature, the narrator doesn’t want anything.

This is because they are written in the Romantic style.

In tales influenced by the Romance era, character desire is less important than mood and symbolism. Romantic poets weren’t about creating an active participant, giving them a goal then showing the audience how they go after it, foiled at every turn. Instead, Romantic characters are tortured souls, the original Goths, haunted by poetry, at the whims of strong forces, often supernatural, outside their control and understanding.

ROMANTICISM AND CHARACTER DESIRE

Angela Carter retains Romantic characterisation in her re-visioning. Like Goethe’s ballad, we know nothing about what the characters want. We don’t know where the father and son had been, for what purpose. We don’t know what the Erl-King wants with the boy (and it doesn’t bear thinking about). I suspect contemporary audiences of Goethe would not have even asked why the Erl-King wanted the boy; nor would they have asked why Rumpelstiltskin wanted a firstborn in exchange for spinning straw into gold. Babies, especially boy babies, were considered desirable alongside gold. Everyone wants gold and everyone wants a baby. This is assumed fact.

OPPONENT

The heroine knows that the Erl-King (nature) could kill her. She seems to believe in some kind of reincarnation and tells us ‘He could thrust me into the seed-bed of next year’s generation and I would have to wait until he whistled me up from my darkness before I could come back again.’

He wields a magic over her. When he beckons, she comes, both literally and sexually. He beckons her to his cottage in the woods where he vampirically sinks his teeth into her neck, draining the life force out of her.

ERL-KING AS CHIMERA

Angela Carter, as Anton Pieck does his illustration above, does not create an outright hideous Erl-King. Pieck creates a pretty regular old man. If Angela Carter’s Erl-King is hideous, this is because of his chimerical one-ness with leaves and the earth. But chimeras throughout the history of art are often depicted as sexually alluring characters. (Take a look at some of the classic art in this post.)

Carter uses the colour green to connect the Erl-King to the fairy realm. Fairies and green are closely associated throughout folklore: ‘Eyes green as apples. Green as dead sea fruit.’

PLAN

Driven by her awe of nature, the narrator enters the subconscious/forest, follows the Erl-King, enters his cottage and lies on his bed.

To call this a ‘plan’ is a bit of a stretch. Whatever it is, it’s the Romantic equivalent. This narrator is under some kind of influence bigger than themselves. Awe and horniness are both forms of arousal, and it seems a legit theory to me that sometimes they become conflated. I suspect this is what goes on in the minds of pyromaniacs, both awed by their own ability to create catastrophic damage and also sexually aroused by it (accounting for the young male demographic skew), though it’s a point of pride that I will never fully understand the urge to light murderous fires at the peak of an Australian summer.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

All of Carter’s pre-introduced moments of spatial horror culminate at the climax of “The Erl-King”: the description of the Erl-King’s eyes, a blend of claustrophobia, warped perspective and the whirlpool effect.

WARPED PERSPECTIVE

By comparing his eyes to a mirror, Carter even manages a fresh take on mise en abyme. Note how she plays with warped perspective:

What big eyes you have [RED RIDING HOOD REFERENCE]. Eyes of an incomparable luminosity, the numinous phosphorescence of the eyes of lycanthropes. The gelid green of your eyes fixes my reflective face [MISE EN ABYME, MIRROR]. It is a preservative, like a green liquid amber; it catches me. I am afraid I will be trapped [CLAUSTROPHOBIA] in it for ever like the poor little ants and flies that stuck their feet in resin before the sea covered the Baltic. He winds me into the circle [WHIRLPOOL] of his eye on a reel of birdsong. There is a black hole in the middle of both your eyes; it is there still centre, looking there makes me giddy [DIZZINESS], as if I might fall into it [VERTIGO].

Your green eye is a reducing chamber. If I look into it long enough, I will become as small as my own reflection. I will diminish to a point and vanish. I will be drawn down into that black whirlpool and be consumed by you.

Angela Carter

THE REDUCING CHAMBER

I looked up ‘reducing chamber’ wondering if it were a real world contraption but it appears to be a fantasy technology invented by Carter, perhaps a riff on the decompression chamber utilised by scuba divers. The ‘chamber’ is another type of cage.

Now the reason for all of this spatial horror becomes apparent:

I shall become so small you can keep me in one of your osier cages and mock my loss of liberty. I have seen the cage you are weaving for me; it is a very pretty one and I shall sit, hereafter, in my cage among the other singing birds but I — I shall be dumb, from spite.

Angela Carter

ANAGNORISIS

Welp, the narrator is beholden to him now. Captured by a rush of love hormones, he might as well have locked our narrator in a cage using allure alone, though she entered into this arrangement supposedly of her own volition, knowing her fate full well.

This uneasy combo of choice versus being drawn in reminds me of something said by James Flynn (before he became so controversial) when asked in an interview why young women keep having babies if children so clearly make poor women’s life worse. His response was that procreation is a human impulse, and we should not expect anyone to restrain it in the face of economic logic. Also, for the least privileged women of all, having children is a logical way to live a meaningful life, far more logical a choice than a privileged outsider often assumes.

In Angela Carter’s lifetime, matrimony for women, despite its restrictions, was the safest, most logical way for many women to live their lives. Matrimony itself was an allure as much as a gilded cage.

NEW SITUATION

The narrator secretly plans to kill the Erl-King and tells the reader exactly how she means to do it. It involves cutting off the Erl-King’s hair. But will she? Does she have a hope in hell against this supernatural creature who can shrink people and stuff them into bird cages? Doubt it. If this were ever going to happen, I’d expect Carter would show it. She didn’t exactly shy away.

There is no escape from patriarchy, even if there is escape from matrimony in individual cases.

This is therefore an example of a story which goes from entrapment to brief freedom in the form of ecstasy, back to entrapment. This makes the story a tragedy. We always equate freedom with happiness.

Our narrator will eke out a living imaginatively, ie., by imagining how she might kill her captor.

A related take

The reflection [in the Erl-King’s eyes at the climax] could be symbolic of the view of these women from the perspective of the male figure, which holds them in a particular image that they have trouble finding their way out of. The narrator, at the end, plans to find her way out, though; still, she has to ask him to turn his gaze away first before she can do so.

MIRRORS, REFLECTIONS IN ANGELA CARTER’S THE BLOODY CHAMBER

The narrator is also comforted by the fact they are not alone. Take for example the cock robin, whose plumage implies it has been stabbed in the heart. (Note how Carter also used the ‘wedding’ ring around the pigeon’s neck — part of its plumage — for symbolic reasons.)

(Robins have long been illustrated dead with their legs in the air.)

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Surface reading

The narrator is terrified of a sexual encounter with the Erl-King but because they’re under some kind of magic spell, they’re required to go through with it anyway.

A feminist reading

The struggle is between the narrator’s wish for freedom from the patriarchal nature of partnership with a ‘king’ (archetypically identical to ‘father’ in fairytales), and their simultaneous sexual attraction to these king-fathers.

When we consider this story and its place within a real world that still runs by the rules of patriarchy, Carter illuminates the relationship between sex, gender, power and entrapment.

FURTHER READING

People who have come out of emotionally abusive relationships often explain that love for a coercive controller acts as an invisible cage. This story is the perfect allegory for that.

An episode of Dear Sugar Radio features an episode called Emotional Abuse, and Steve Almond mentions another short story which also makes an excellent allegory: “Runaway” by Alice Munro.

Franz Schubert: Erlkönig on YouTube

Header painting: Moritz von Schwind, Illustration to Goethe’s Poem “Erlkönig”, 1849.