I recently looked into The Magic Porridge Pot (a.k.a. Sweet Porridge), part of a whole category of folk tales about pots of overflowing food. Related, there is another category of folk tales about food that runs away. In the West, the most famous of those would have to be The Gingerbread Man, but have you also heard of The Fleeing Pancake? Best name for a folk tale ever.

Also in this category we have:

- The Bear Ate Them Up

- The Bun

- The Fate of Mr. Jack Sparrow

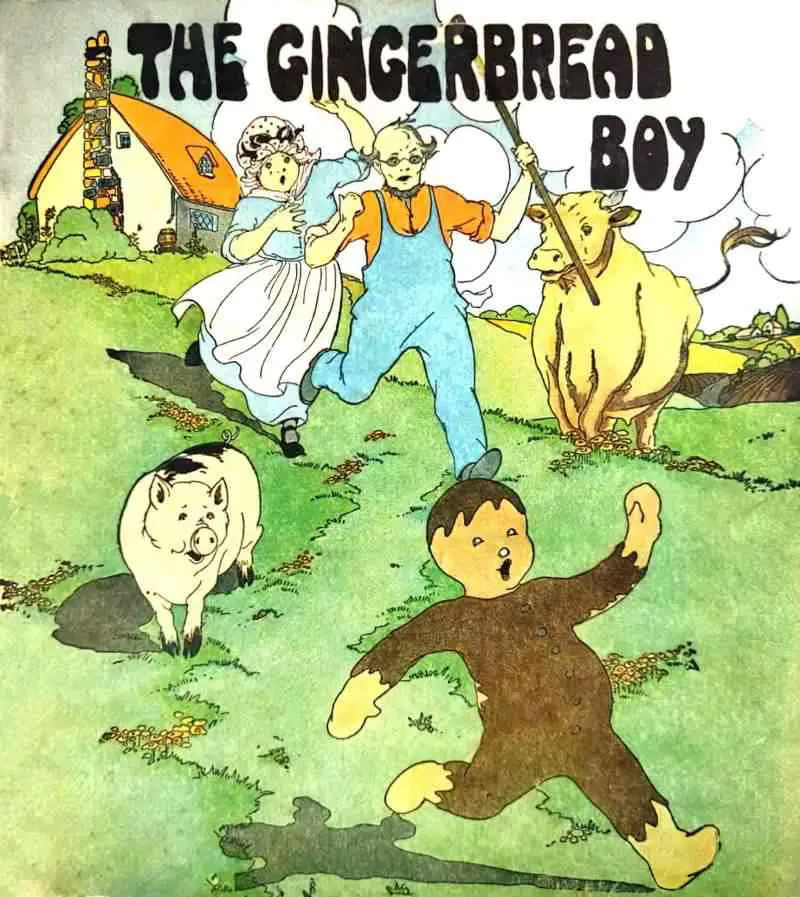

- The Gingerbread Boy

- Johnny-Cake

- The Johnny Cake Boy

- The Little Cake

- The Pancake

- The Runaway Pancake

- The Thick, Fat Pancake

- The Wee Bannock

As you can see, bread-like products are more likely to run off than, say, meat. I find this comforting. That said, the Hungarian version stars ‘head cheese’. I’m not sure what to think of that. Sometimes the gingerbread isn’t actually fashioned into the form of a toilet symbol, either — sometimes it’s just a ball of dough.

For comparison you might take Julia Donaldson’s Stick Man, which I have already analysed in detail. Donaldson is a master at remixing old stories into rhyming texts for a contemporary audience. Stick Man is a remix of The Gingerbread Man.

WHERE TO HEAR THE GINGERBEAD MAN READ ALOUD

If you’d like to hear “The Gingerbread Man” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “The Gingerbread Man” was published May 2019.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE GINGERBREAD MAN

WHO IS THE MAIN CHARACTER?

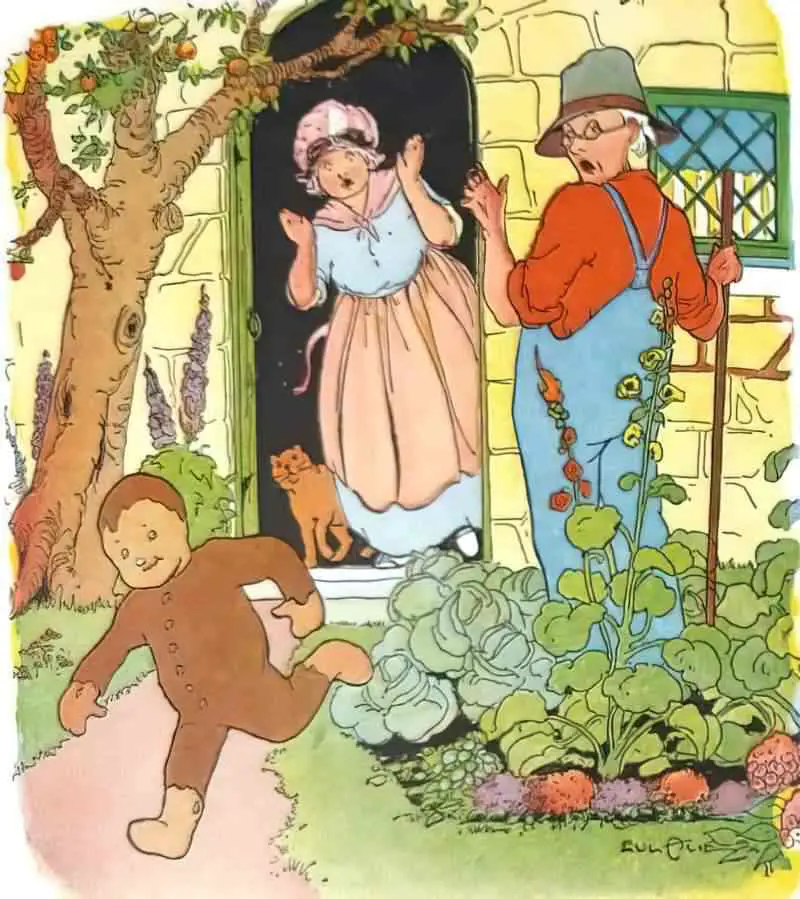

In stories this isn’t always obvious, but it is in this one. The main character is The Gingerbread Man! We see him the most, we want him to succeed in getting away and he is in every single scene.

Next question before moving on: What is The Gingerbread Man’s shortcoming?

Well, he’s a bit of a show off, isn’t he. He’s also a bit naive. Fresh out of the oven, he doesn’t realise that fairytale foxes are wily. If only he’d read a few fairytales he’d know what we already know about foxes in picture books!

WHAT DOES THE GINGERBREAD MAN WANT?

Freedom.

Or does he?

What he really wants is to prove how fast he is at running. Over and over again he says, “You can’t catch me!” His haughtiness eventually catches up with him. It’s like he’s taunting everyone to catch him. If he’d just run without all that singing, he wouldn’t have drawn attention to himself and he would’ve probably got away.

OPPONENT/MONSTER/BADDIE/ENEMY/FRENEMY

The Gingerbread Man is a classic example of mythical structure. This has nothing to do with being an actual myth. A myth is a traditional story, especially one concerning the early history of a people or explaining a natural or social phenomenon, and typically involving supernatural beings or events. The Gingerbread Man is a pretty old tale, but it’s not a myth. I’m talking about how many more modern stories borrow the plot from those old myths.

I’ve written about mythic structure here. Basically, your main character goes on a journey, meets a bunch of characters — some helpful, some mean — ends up fighting a big big struggle then returns home again a changed character. Or if he can’t make it home, he finds a new home. That’s mythic structure. It’s still very popular. The Lion King, Diary of a Wimpy Kid The Long Haul and Beauty and the Beast all have mythic structure. Or you might have seen The Incredible Journey, or Where The Red Fern Grows. In all of these stories the main character goes on a journey.

In fact, any boardgame where you need to go from square to square to reach a goal is making use of mythic structure. Along your ‘route’ you’ll slide down snakes (opponents), be helped by ladders (mentors), go back three squares, go forward two squares and so on.

The Gingerbread Man also goes on a journey, though he has no idea where he’s going. He’s just running. Everyone he meets wants to eat him (we assume), so everyone is his enemy. (It’s partly his own fault for being so delicious!) Usually in a mythic structure our main character encounters ‘helpers’ or ‘mentors’, but The Gingerbread is such an annoying character he doesn’t meet any of those.

WHAT’S THE PLAN?

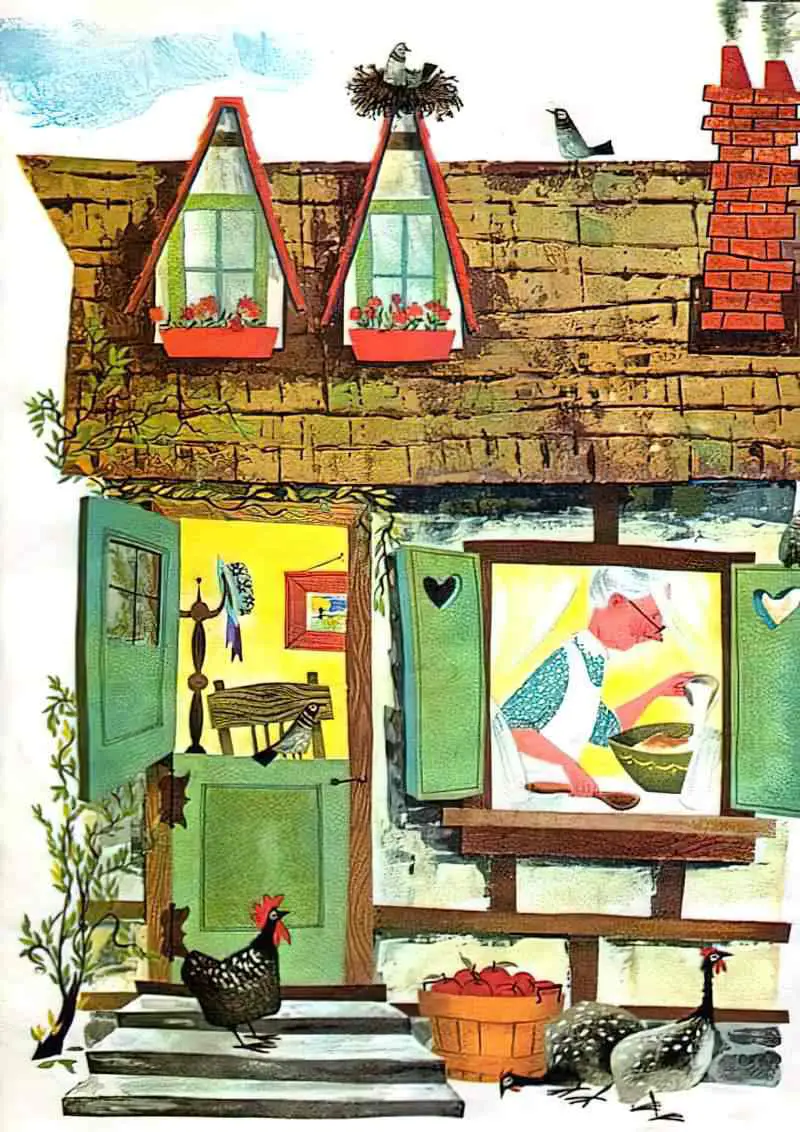

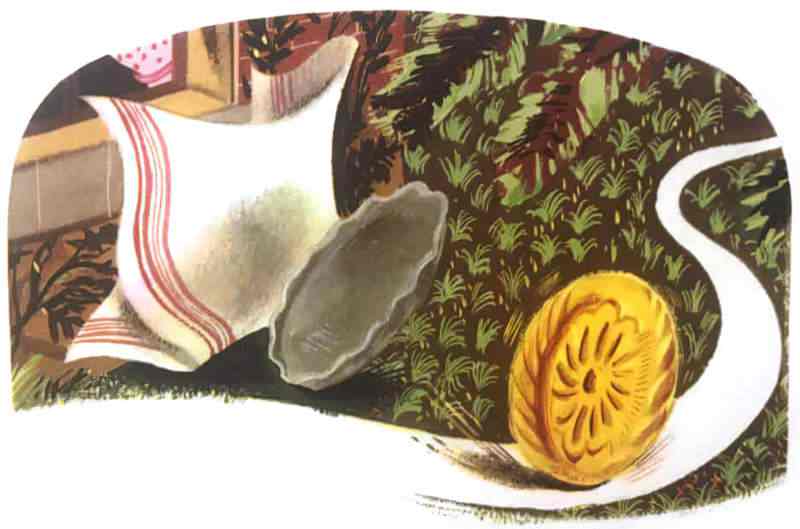

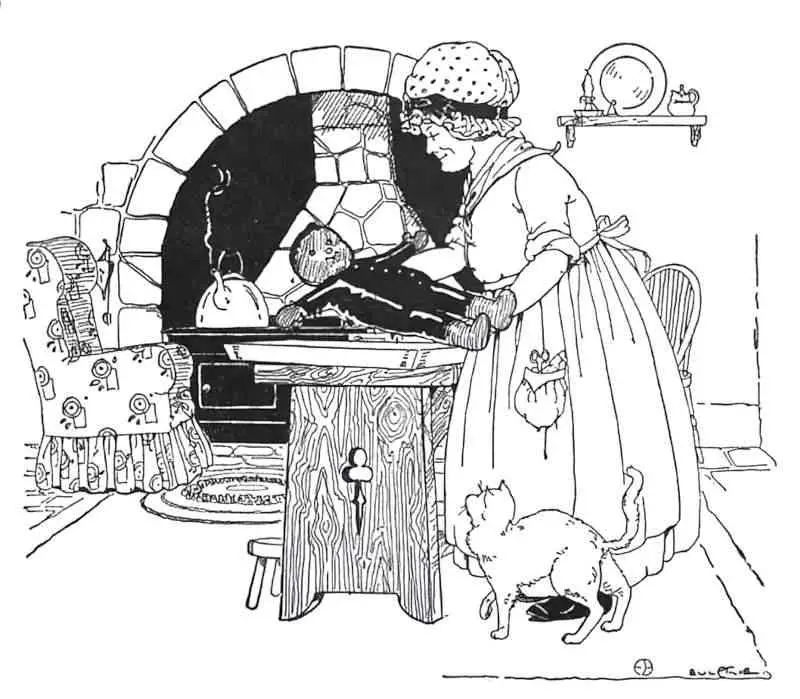

Sometimes other characters have more plans than the main character. In this story, the old lady had a reasonably complicated plan to bake and decorate a gingerbread man, then to eat him.

But this is not about her.

The Gingerbread Man demonstrates that plans don’t have to be complicated. It’s true that in most stories plans are a BIT more complicated than JUST RUN REALLY FAST. It is also true that in most stories original plans don’t work and they need to be modified. This is a simple tale, known as a ‘cumulative’ story. Another example is There Was An Old Lady Who Swallowed A Fly. Young kids love these stories and they are great for language development. The adult co-reader is left reading the same sentences over and over. That’s what happens here, too. Fortunately, it’s pretty fun to say, “Run, run as fast as you can! You can’t catch me, I’m The Gingerbread Man!” If that wasn’t catchy this story wouldn’t have entered mainstream culture. So if you’re going to write a cumulative story like this one, make sure you’ve written something run to read aloud.

tl;dr: The Gingerbread Man plans to run. Until he is free, I suppose.

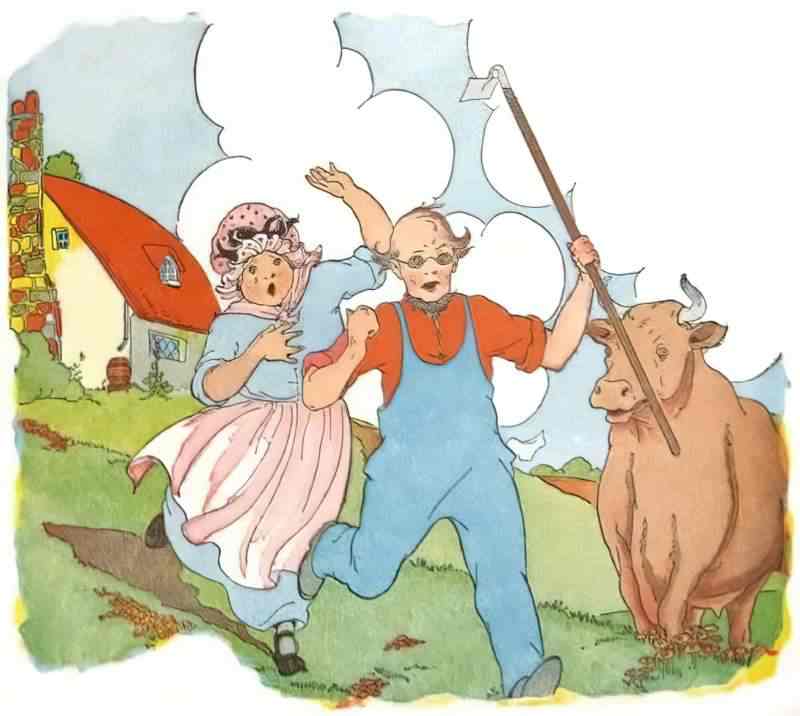

BIG STRUGGLE

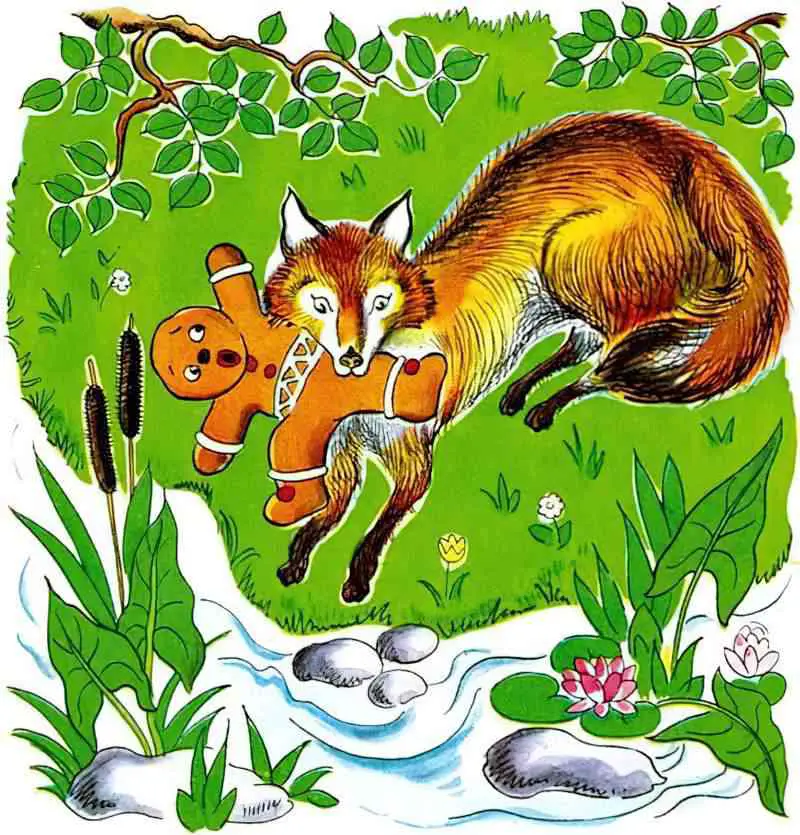

The fox!

Notice the nice lead up? The Gingerbread Man sits first on the fox’s tail. The fox slowly coaxes him towards his nose and then SNAP!

WHAT DOES THE GINGERBREAD MAN LEARN?

Well, he’s dead so he doesn’t learn anything.

The Gingerbread Man is therefore a tragedy.

BUT! If he had lived another day, he would have learned not to hitch rides from foxes, and if he did hitch a ride from a fox, he’d know not to sit on the fox’s SNOUT.

Except that’s not really what the story’s about, right? That’s the most surface level of the messages.

Don’t be cocky. That’s what The Gingerbread Man would’ve learnt. And that is hopefully what we learn, as readers. We might think we’re the fastest runners in the whole world, but there’s always someone who can outwit us.

HOW WILL LIFE BE DIFFERENT FROM NOW ON?

Well, he’s dead. The Gingerbread Man is sort of like a work of cosmic horror in that regard. (The main characters of cosmic horror also often end up dead.)

BUT NORMALLY characters aren’t dead at the end of the story. So we get to see our heroes sitting around the fire enjoying wolf stew (like in The Three Little Pigs) or reunited with their father (in Hansel and Gretel).

I haven’t yet seen a picture book version of The Gingerbread Man who has been pooped out. There he is, sitting like a Hersheys chocolate, propped up on a clump of grass.

I haven’t seen that, but I’d like to.

RESONANCE

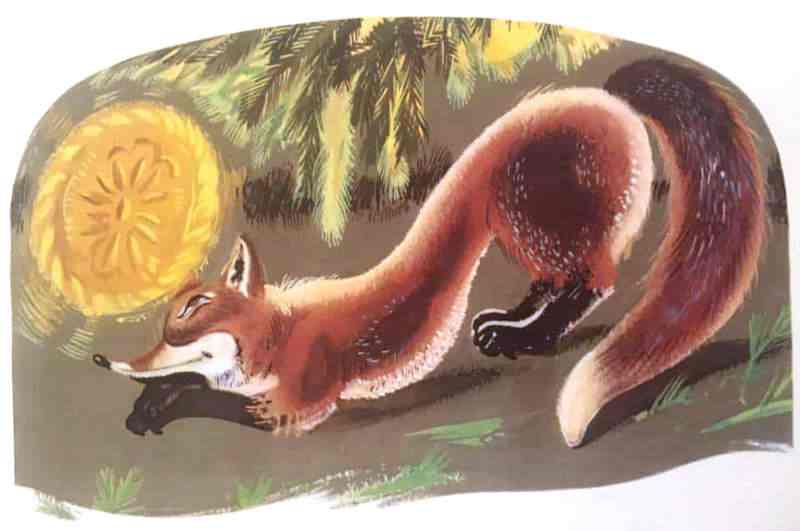

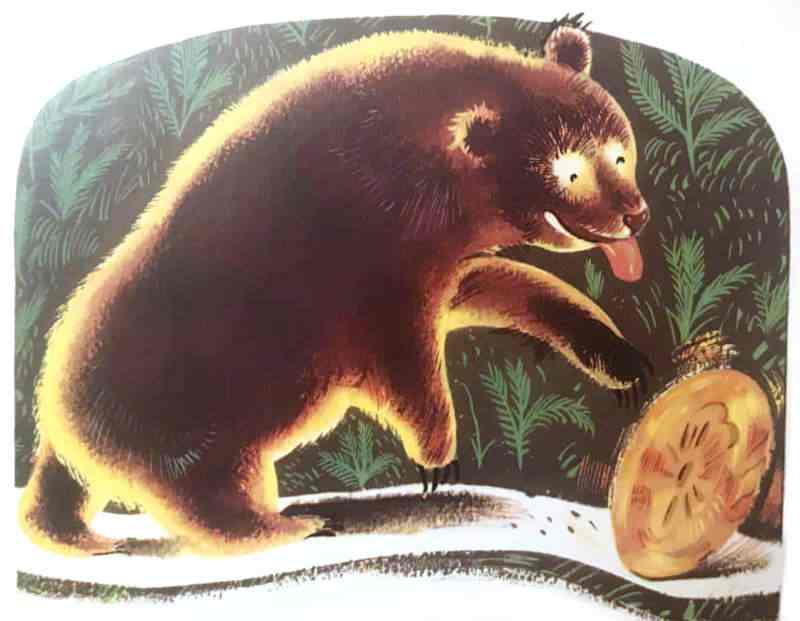

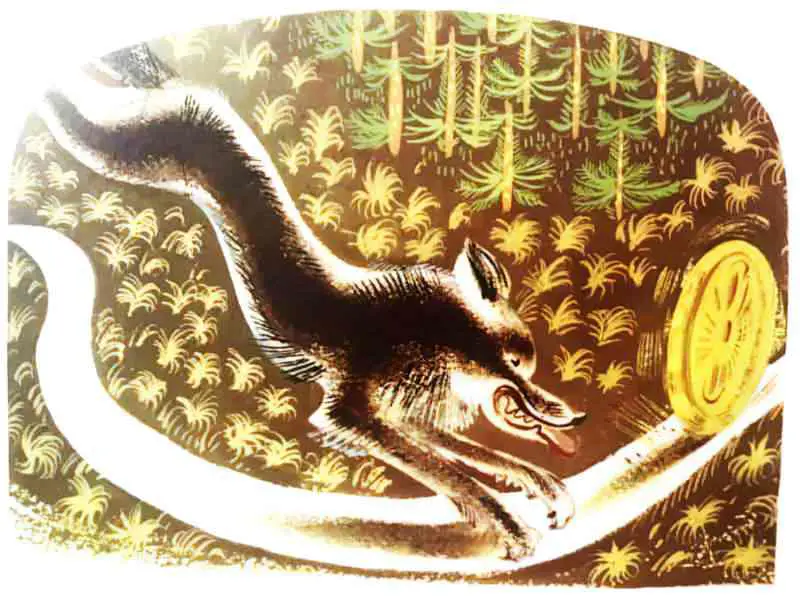

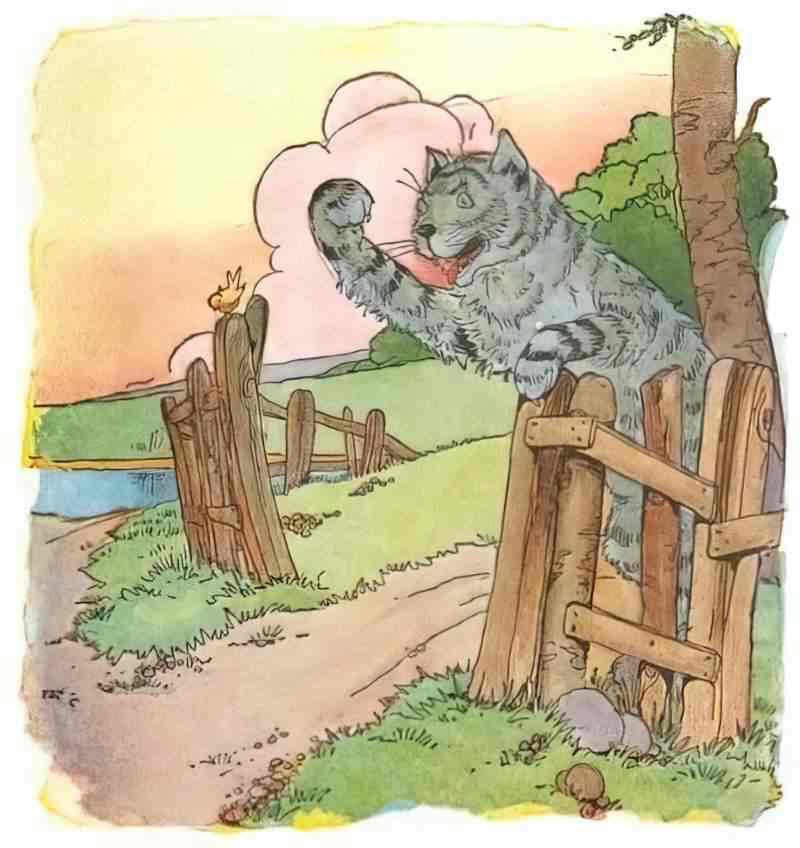

Around the world there are many variations on the baked goods running away story, chased by a cumulative array of animals. The example below happens to be French.

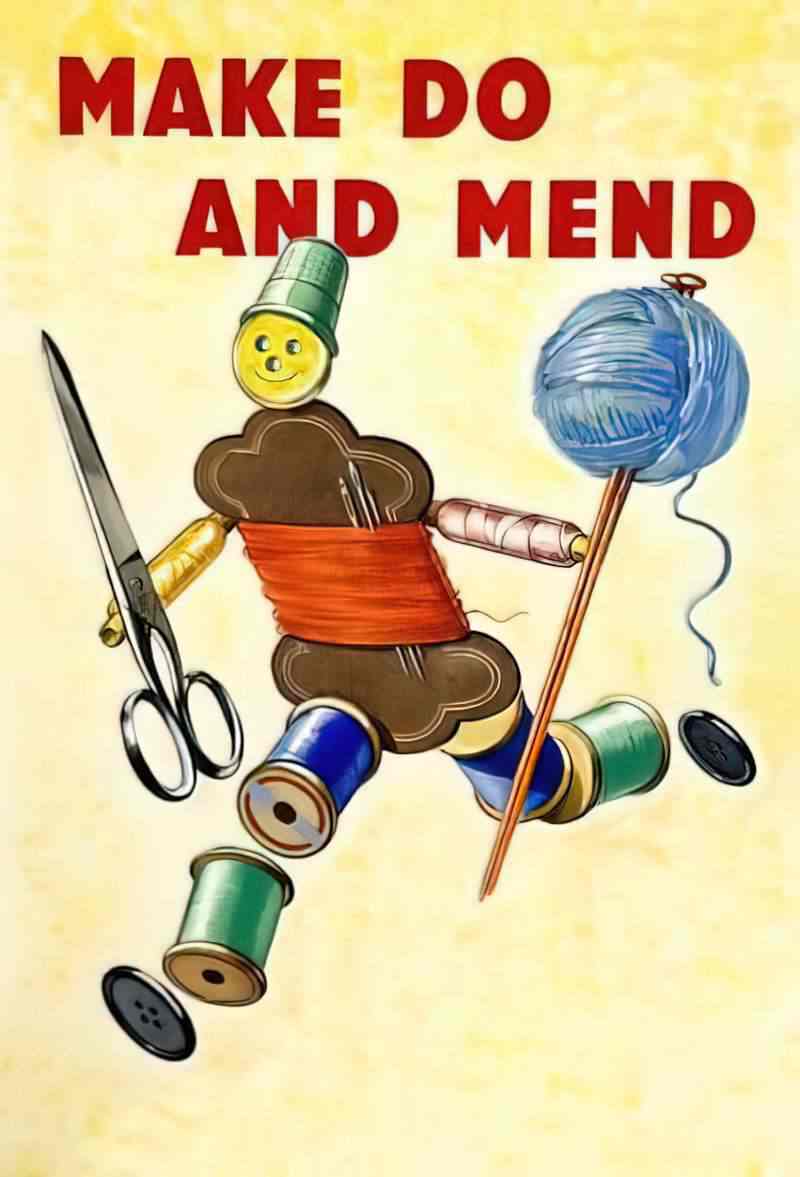

The image of the Gingerbread Man is so well-known, you’ll see intratextual references to it elsewhere, for example in this British poster from World War Two.

A Performance Tale

What makes ‘The Gingerbread Man’ such an enduring classic? This is a great example of a tale that’s satisfying to read aloud, or rather, to perform. First we have the arc phrase, repeated and easily remembered: Run, run, as fast as you can! This is even a phrase that can be used in other circumstances, like in a game of chase.

Then the teller has the chance to snap their arms like a crocodile at the climax. This is very similar to the way Little Red Riding Hood was originally designed to be performed, when the wolf gobbles up Little Red Riding Hood. Listeners enjoy the frisson of excitement, knowing that the death is imminent, able to enjoy the same tale over and over again. Another tale that works like this is The Little Red Hen, with much repetition and a climax that can be performed.

The Gingerbread Man is meant for performance but first made it into print in 1875, in a magazine.

Disneyfication Of The Ending

As a testament to just how far modern adults will go in protecting our children from bad endings, many versions of this tale avoid the original ending, the one in which the gingerbread is dismembered — first a quarter, then a half of him, then only his head is left… This despite him being… a food product. I suspect the amelioration of the ending happened once the gingerbread started looking more and more humanlike, aided by print, due to accompanying illustrations.

Gingerbread People In Modern Stories

Jon Sciezka wrote The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales which was published in 1992 and is now a picturebook well-known for its postmodernism. The Stinky Cheese Man is a retelling of The Gingerbread Man but with a gross out factor. (The cheese man runs away from everyone fearing they will eat him, when really everyone just wants to get away from his smell.)

The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales is the ultimate exercise in metafiction to the point where it parodies metafiction itself.

Playing with Picturebooks: Postmodernism and the Postmodernesque by Cherie Allan

For a comparison between this book and one from the other king of postmodern picturebooks (yes, Anthony Browne), see Voices of the Stinky Cheese Man: A Comparison Study of Two Postmodern Picture Books by Voicu Mihnea Simandan.

You may have also heard of an American author called Stephen King. King also wrote a riff on the Gingerbread tale called The Gingerbread Girl. It’s long enough to be considered a novella and was included in the short story collection Just After Sunset (2008).

Gingerbread Men and Feminism

As you can see from this cover, another faceless woman whose body is the main grab, both for the baddie in the story but also for the reader.

In my middle age I have grown somewhat weary of stories with:

- Women who have child loss as a reason for psychological trauma (see also Gravity, Sandra Bullock’s character)

- Women in ‘fridges’ (or in the boots of cars)

- Exercise induced anorexia nervosa re-visioned as kickass strength.

Experienced readers know, surely, that this particular woman in this particular story is going to overpower the bad man. We forget about all the fictional, faceless, female victims who have come before and are encouraged to rejoice that evil has been overcome… until we read the exact same kind of story again, with a different baddie man and a different but equally good-looking young white woman. This tale has been done too many times to be making any sort of statement, but I predict a defence of this particular version would be that, in using ‘The Gingerbread Man’ folktale as an allusion, King is making deliberate use of the female as a food. But because faceless female victims are consumed so very regularly in fiction, I don’t buy any feminist ‘strong female character’ arguments.

In many versions of the original tale, the little old woman has actually created a live action version of a gingerbread boy to stand in as a surrogate child, as she cannot have her own. Because of course if a woman cannot have her own children she cannot possibly have a fulfilled existence in her own right.

The Gingerbread Man As A Crime Story

The Gingerbread Man has been a popular allusion in modern crime shows. (The folk tale is basically a crime story after all — it should not be legal for properly purchased food products to run off.) Gingerbread is a comfort food associated strongly with the home and hearth, and with family get-togethers. So by pairing these images with crime writers can create ironic juxtaposition. We may eventually get to the point, though, where gingerbread functions much like playgrounds, ice cream vans and clowns for most viewers.

There’s a 1998 film called The Gingerbread Man. It’s a legal thriller but I don’t watch anything that gets less than 6.0 on IMDb so let’s not dwell on that. The Gingerdead Man, however, looks even better, at 3.4.

The Gingerbread Man is also recast as a mass murdering villain in Jasper Fforde’s The Fourth Bear.