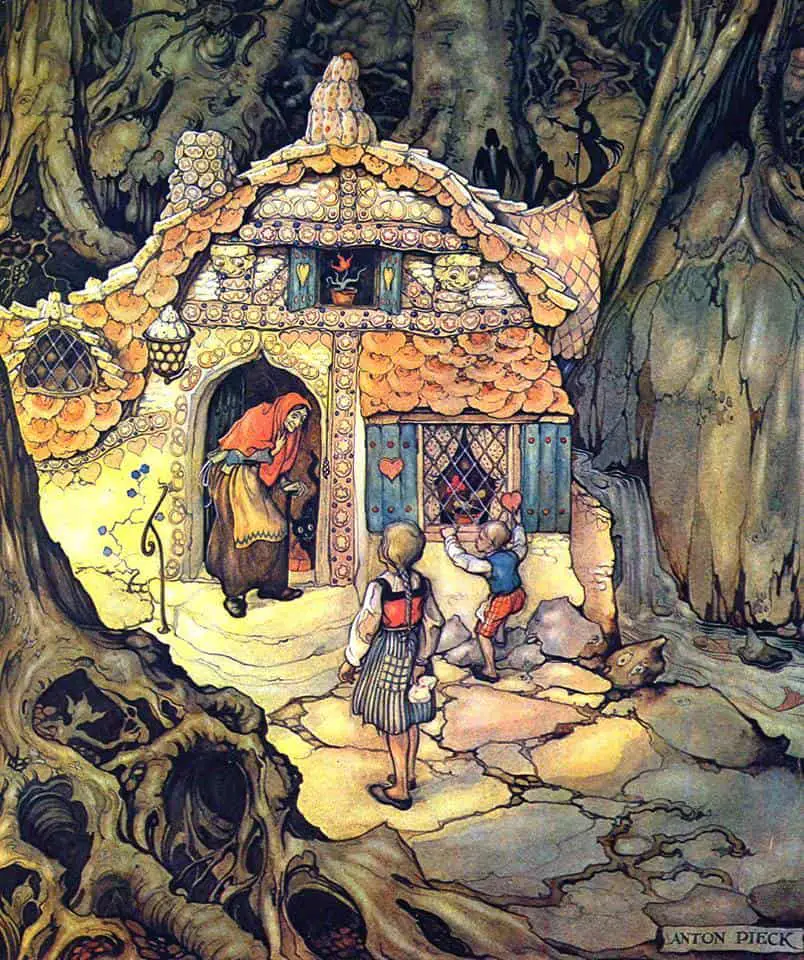

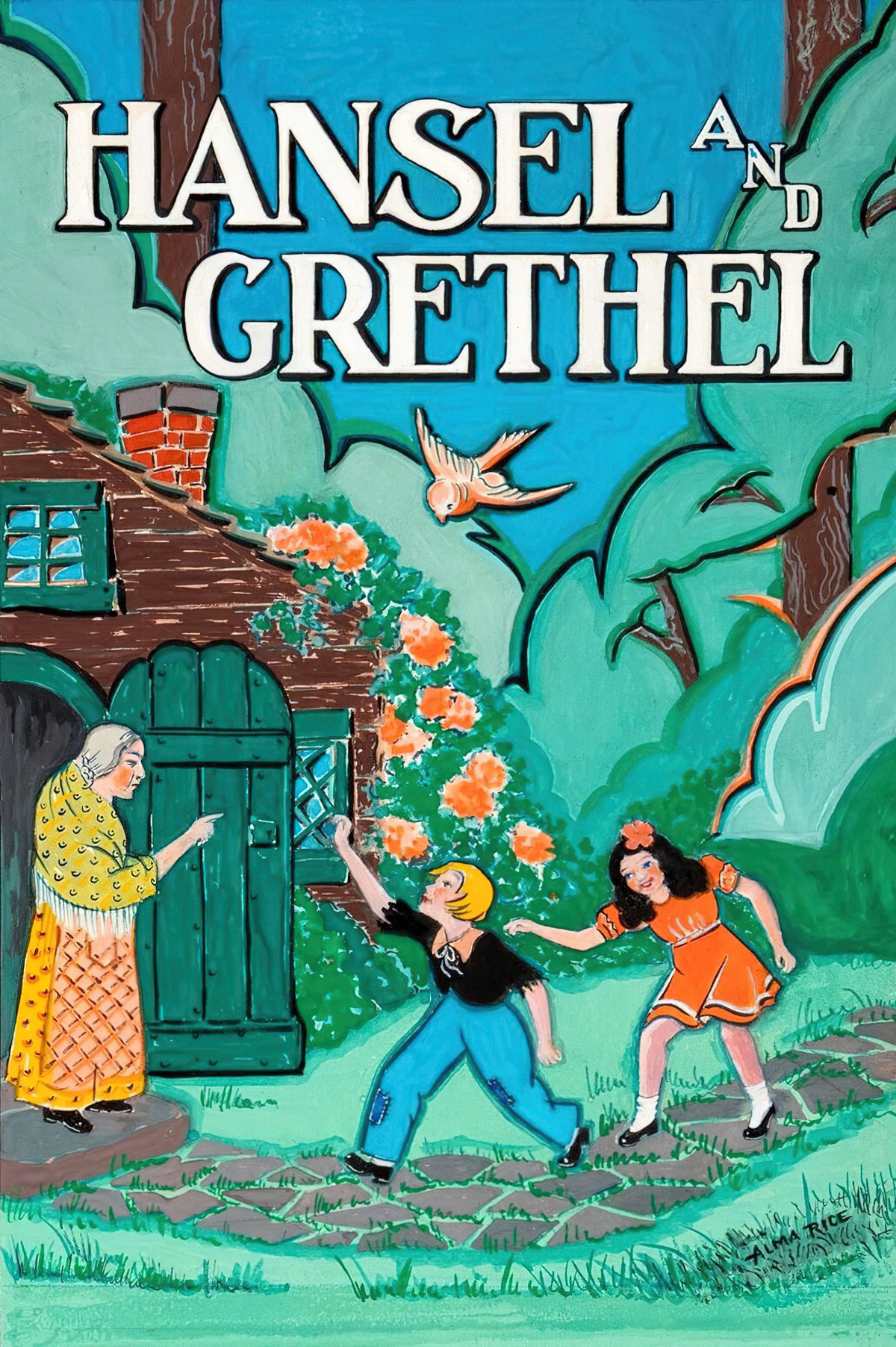

When artists choose to illustrate a single narrative moment, they make a choice of lasting importance, because their illustration creates a memorable impression for an entire story, one that visually anchors an impression of that story in its reader’s memory. Illustration history is full of such memorable moments. In the illustration history of Grimm’s Tales, one image predominates, that of “Hansel and Gretel” beginning to eat the witch’s house.

Ruth Botingheimer, “Illustration and Imagination”

When an illustrator signs on to illustrate a retelling of Hansel and Gretel, I bet the scene they look forward to the most is depicting the gingerbread house. On the other hand, how to make it original?

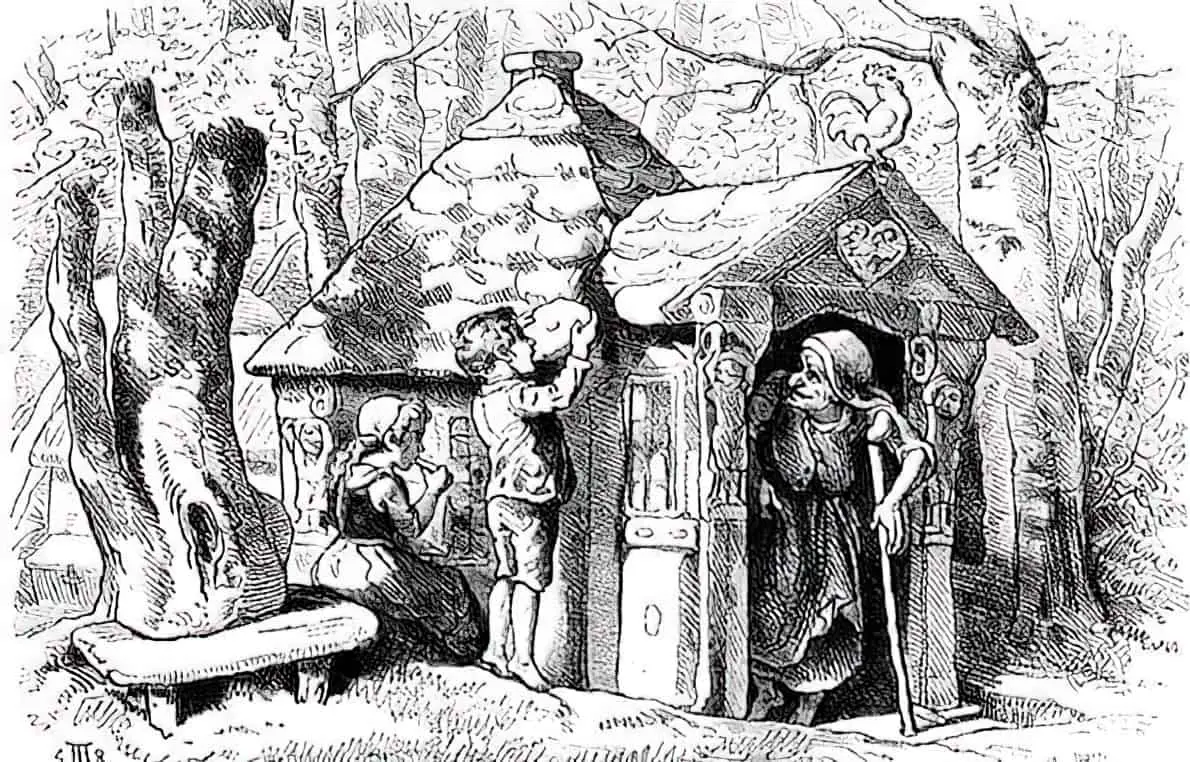

HERMANN VOGEL

Hermann Vogel (1854 – 1921) was a German illustrator who worked for the publishing company Braun & Schneider. He was famous for the artwork which accompanied an 1881 collection of stories by Hans Christian Andersen, and also for an 1887 collection of satirical fairytales by Johann Karl August Musäus.

As well as Hansel and Gretel, Hermann Vogel illustrated well-known fairy tales Bluebeard and The Juniper Tree.

CHARLES JAMES FOLKARD

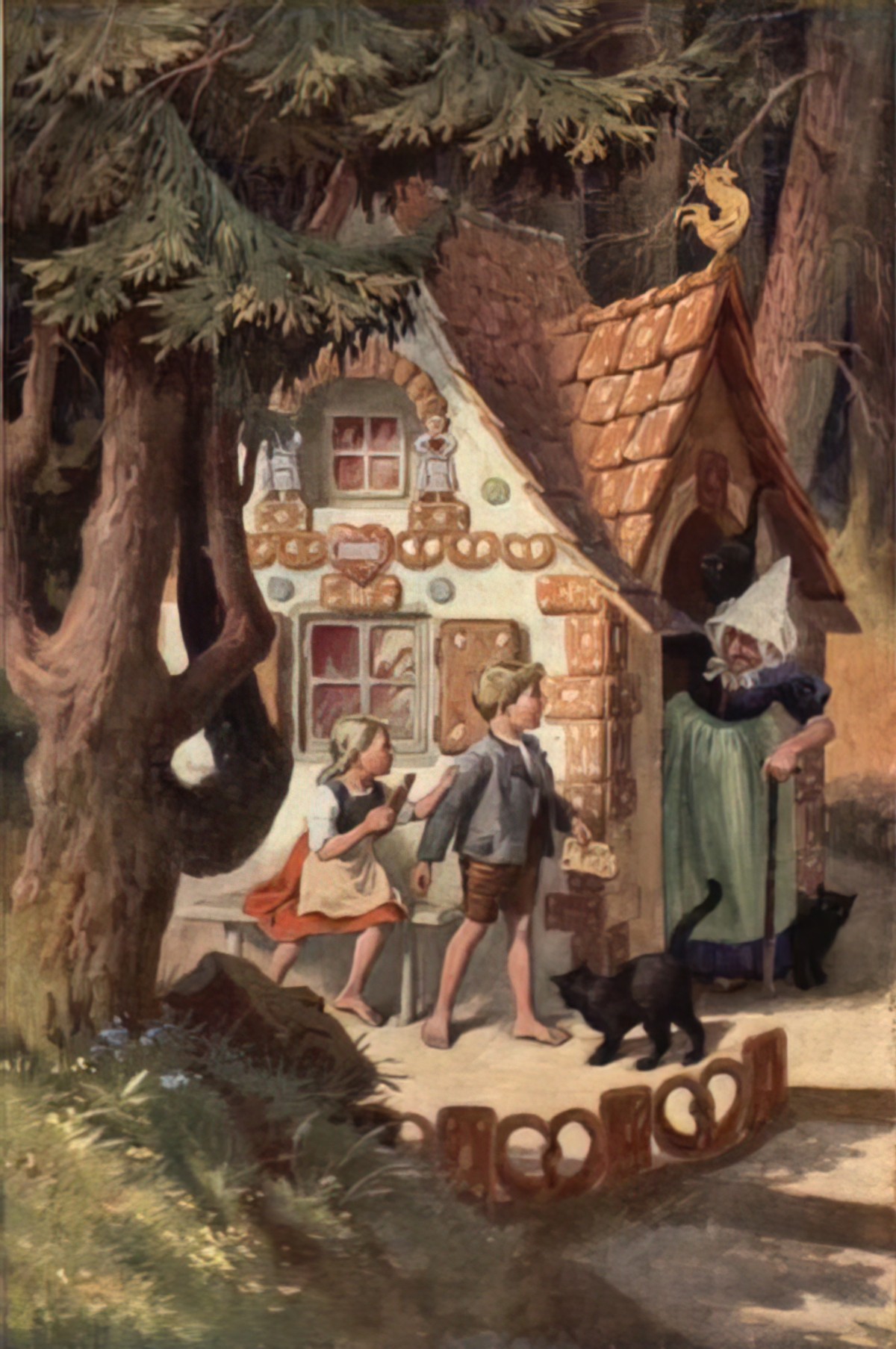

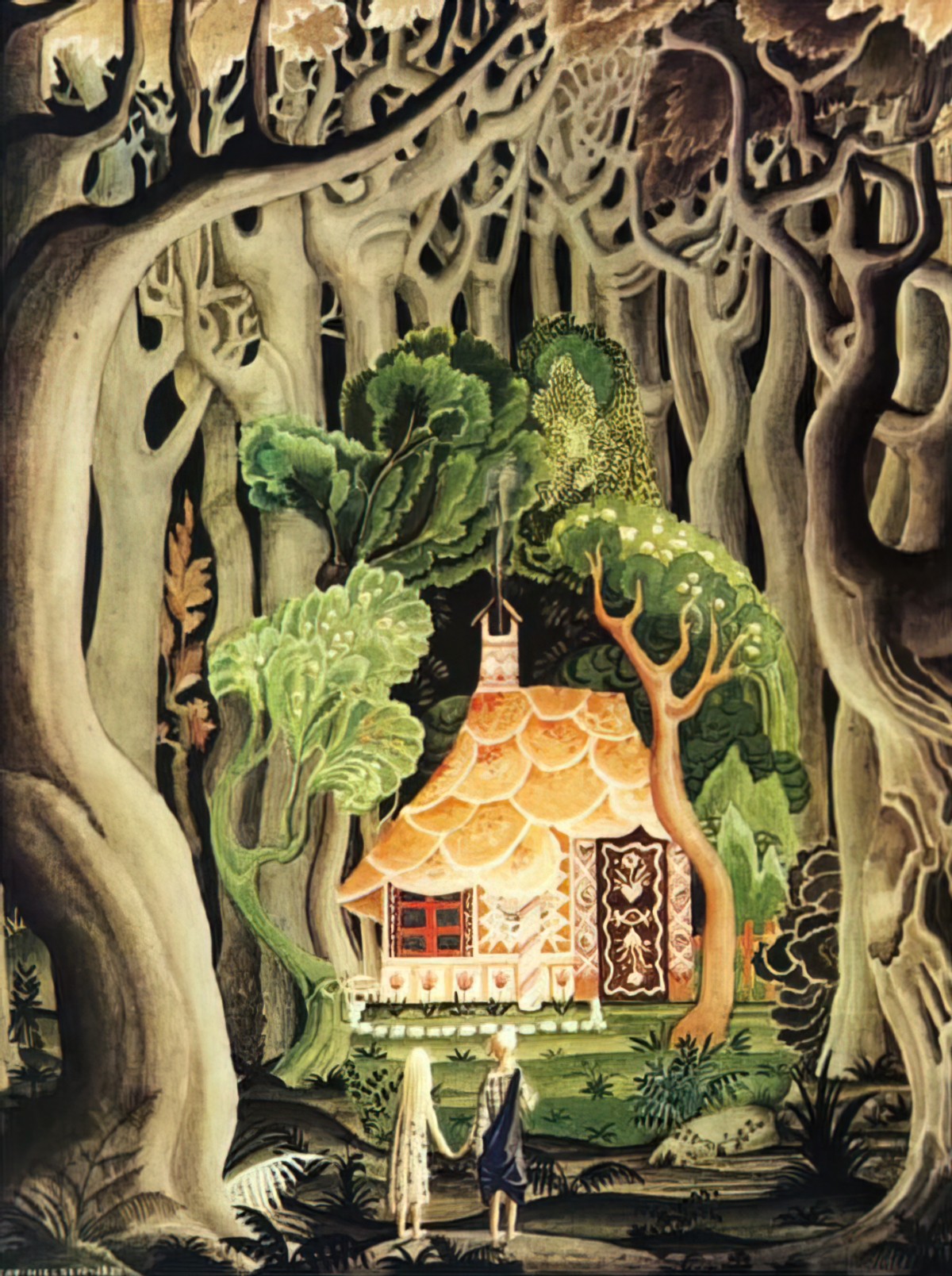

OTTO KUBEL’S GINGERBREAD HOUSE

Kubel added black witch’s cats, which should have alerted the children, really. The children are rosy cheeked and look pretty well-nourished to me. The witch isn’t immediately obvious. The eye is drawn to the children first, catching the ambient light. The witch is dressed in white, but remains standing in shadow. The house is small, closing around her, like the house itself will gobble you up. The foregrounded tree reminds us that we are in the forest.

Otto Kubel was a German painter and illustrator who lived from 1868 – 1951. He studied at the Dresden School of Applied Arts then worked uneventfully, it seems, as an artist and sometimes illustrator of children’s books.

Kubel did live in various different places around Germany: In the early 1900’s Kubel went to live in Furstenfelbruck (a well-known artists colony — home of “Die Brucker Maler”). Next he lived in Munchen where he basically stayed put, apart from the later part of the Second World War in which he stayed in Partenkirchen.

If you can read German, here’s some more about his illustration.

WANDA GAG’S GINGERBREAD HOUSE

Wanda Gag had only black and white to work with. She surrounds the children with white so they don’t disappear by accident into the image. This makes it look as if light emanates from the children themselves. In most depictions of the gingerbread house, light seems to come from the house itself, or out of the surrounding trees. The witch has not yet appeared, but a black cat on teh stoop lies in wait.

See: Wanda Gag’s Americanization Of Grimms’ Fairy Tales a scholarly paper from Jack Zipes.

- Wanda Gag made the Grimms’ fairy tales popular in America during the 1930s and 1940s, which is when anti-German sentiment was on the rise.

- Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, as produced by Disney in 1937, helped when it came to popularising these German tales across the Atlantic.

- Wanda Gag was born in 1893.

- She was the daughter of a ‘free-thinking painter’ with seven children who he couldn’t feed properly. This might explain partly why Gag felt so drawn to a tale which is ultimately about starving children? Her father died when she was only 15, too. It’s possible she idolised him in the same way the tale idolises paternity (and vilifies maternity).

- Gag is most famous for her book Millions of Cats.

- She died in 1948, before she had finished the job she had set out to do, which was to translate and illustrate 50 of the Grimm tales.

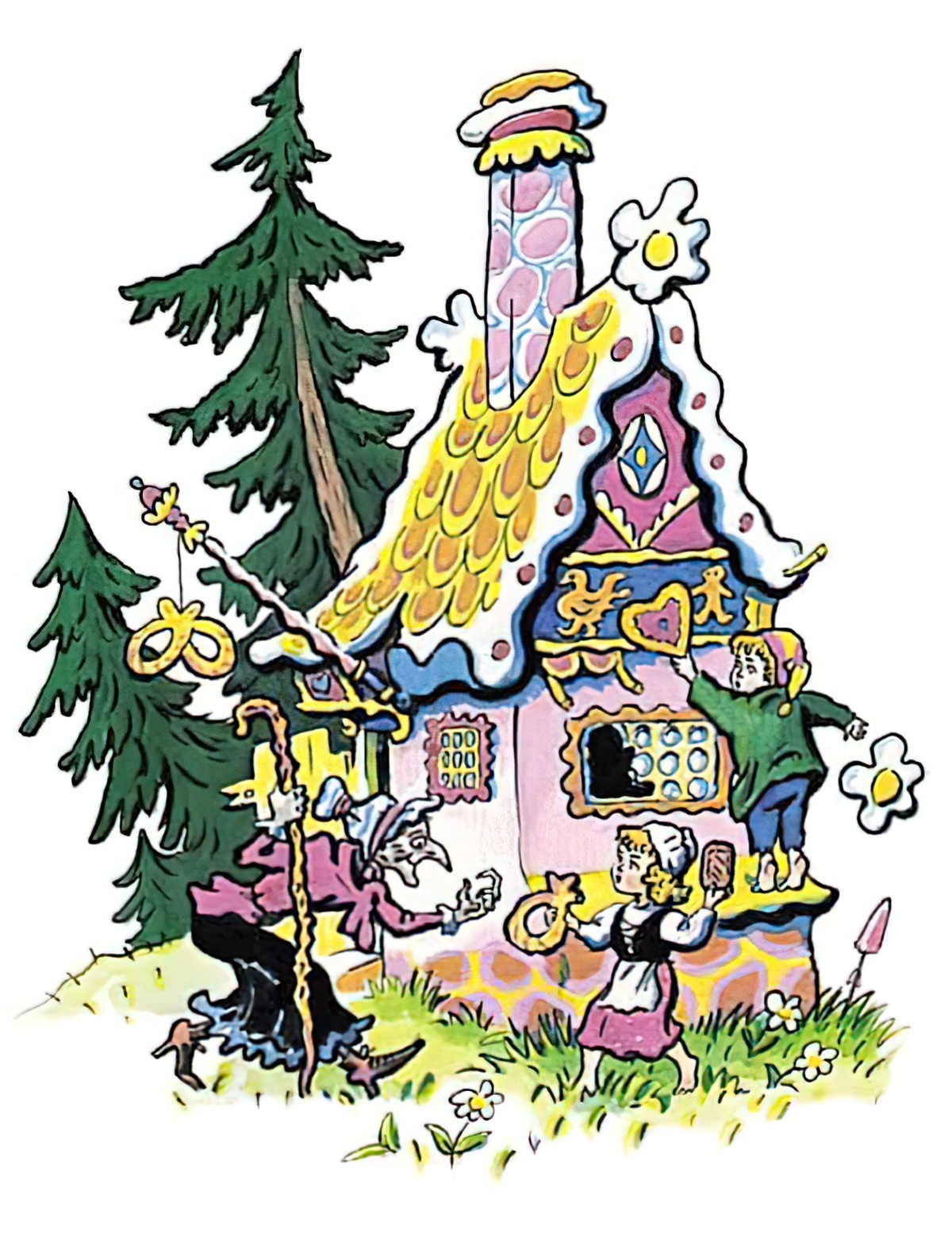

VLADIMIR VTORENKO

ANASTASIA ARKHIPOVA

Anastasia Arkhipova is an artist living in Moscow. She comes from an artistic family. Her father and grandfather were also book illustrators. But she formally learned the craft from well-known illustrator Boris Alexandrovich Dekhterev (1908 – 1993). She’s been a working illustrator since she was a student.

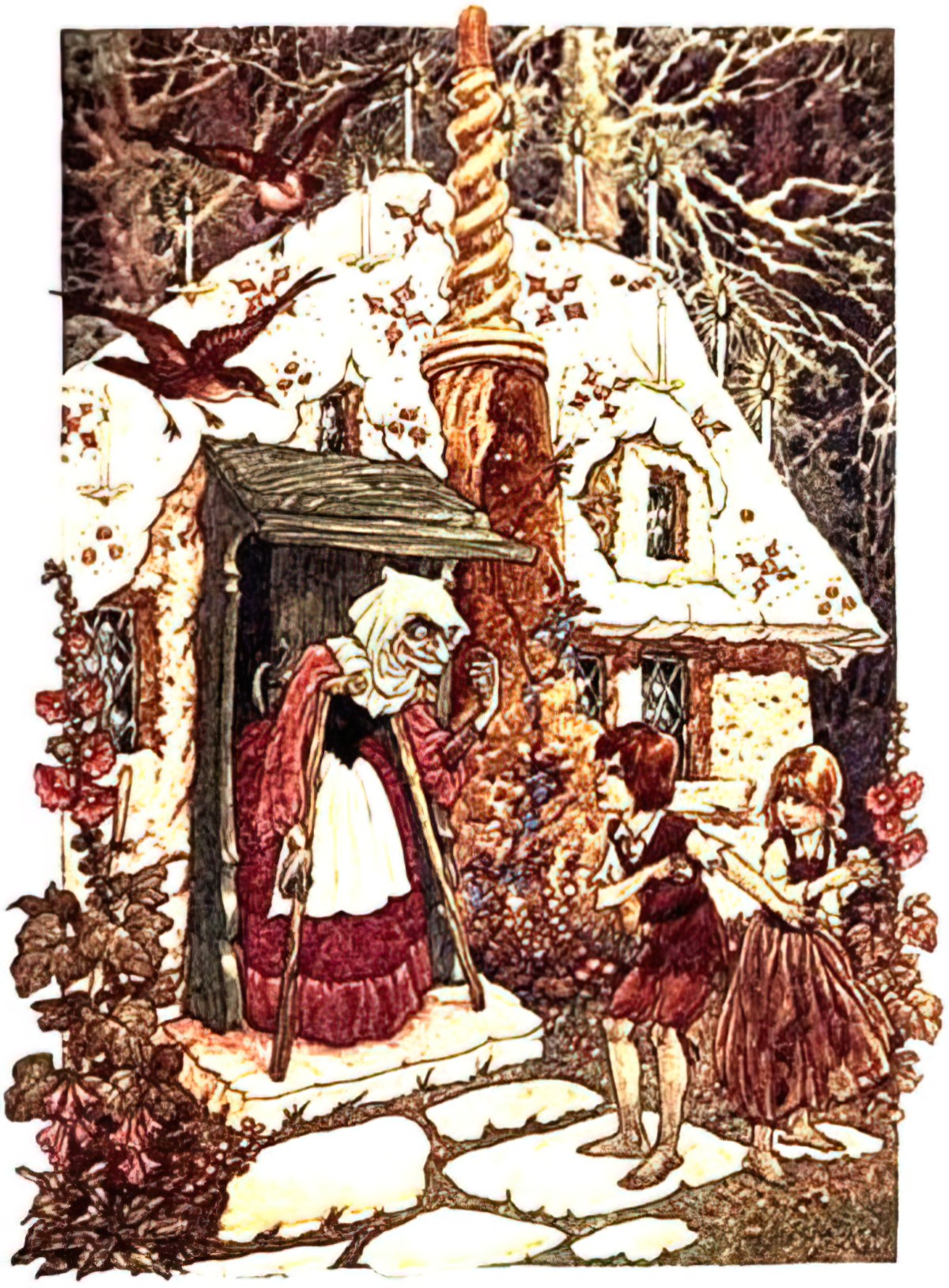

KAY NIELSON’S GINGERBREAD HOUSE

These children look a bit thinner than many other depictions. The trees are absolutely huge. The foliage growing around the house is affected by its magical aura and is therefore green, even though all the other trees are in ochres. There’s a soft curviness to this illustration. The only hard angles are the windows and chimney. Light comes from the house, somehow.

Kay Nielsen was a so-called Golden Age illustrator from Denmark who lived from 1886-1957. (Despite the name Kay being largely a feminine name in the West, in Denmark it is a masculine name.) Like Wanda Gag, he came from a highly artistic family. In 1939 he moved to California and because he was a white man and also good at art, he secured a job working for Disney. Can you guess which movie he worked on, judging by his style?

Well, he did some concept paintings for The Little Mermaid. His work was used in the “Ave Maria” and “Night on Bald Mountain” sequences of Fantasia. (Here’s the thing about that movie: It wasn’t actually produced until 1989. Nielsen died a long time before then.)

Walt Disney only employed him for four years. He had to return to Denmark, where he spent his final years. Unfortunately, trends had moved on, and Nielsen’s style of illustration was no longer in fashion.

FELICITAS KUHN

Felicitas Kuhn (born 3 1926) is an Austrian children’s book illustrator born in Vienna. She started paid illustrating work in the 1940s, then retired a short while later in 1957.

SVETLANA KIM

Russian-Ukrainian illustrator Svetlana Kim was born in 1947.

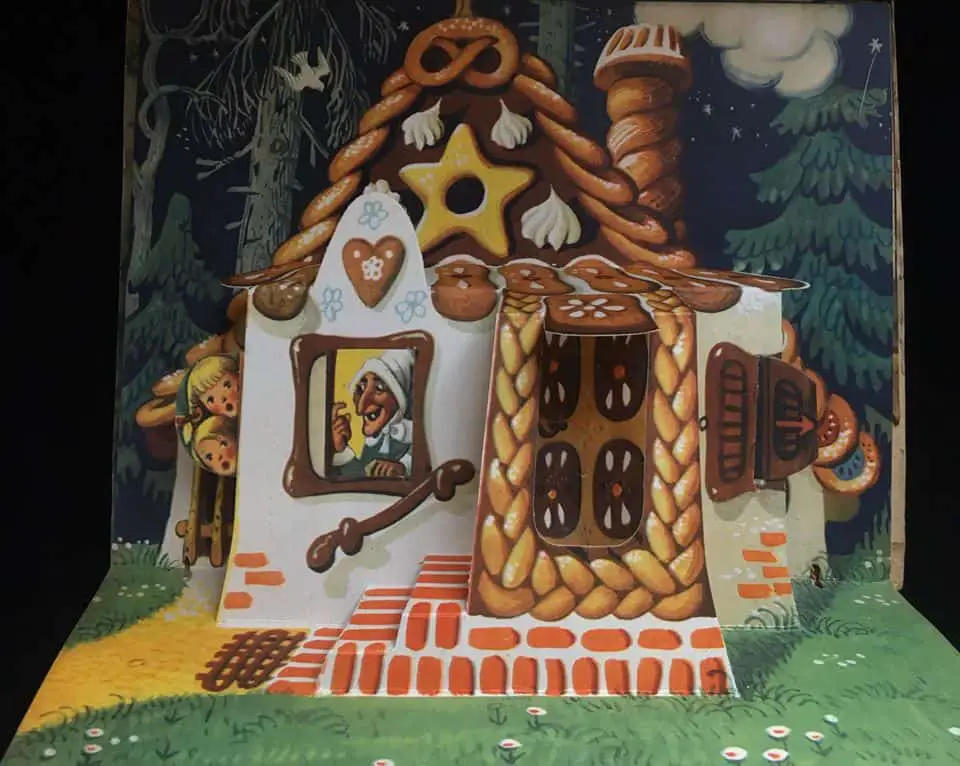

VOJTECH KUBASTA

Vojtěch Kubašta (1914 – 1992) was a Czech artist as well as an architect, so we might expect him to really enjoy creating pop-up houses, including fantasy houses such as one made of gingerbread. Kubašta was actually born in Vienna but moved to The Czech Republic (as it is known today) at the age of four.

He got into pop-up (three dimensional) art after 1948, when the Czech communist government made it very difficult to work in publishing. So he started making three-dimensional cards which advertised products: porcelain, sewing machines and what-not.

His first pop-up book was Little Red Riding Hood.

Today, Kubašta is considerd a world pioneer of pop-up books for children. There is a profile of him at The New York Times (possible paywall).

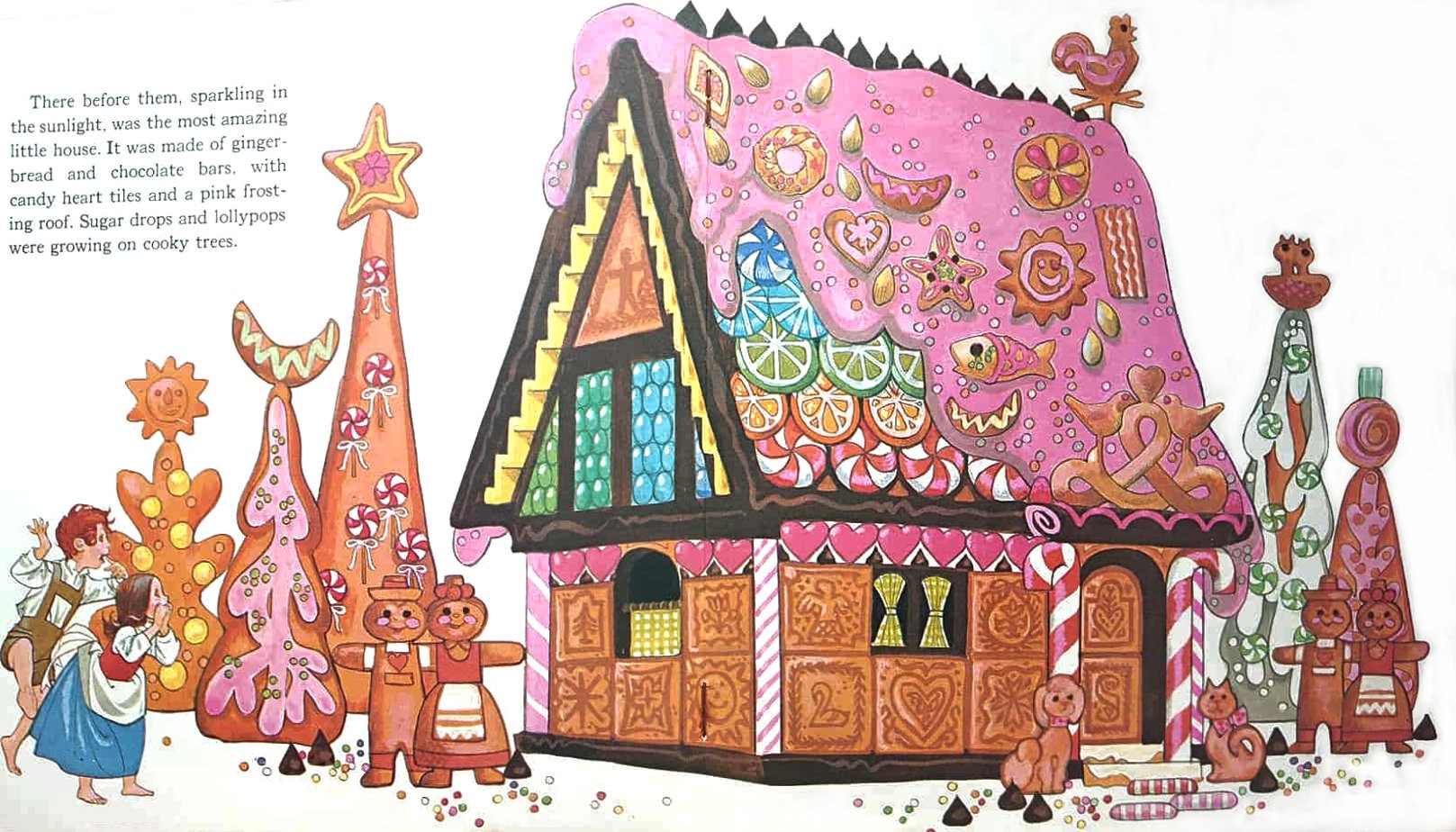

SHEILAH BECKETT

American illustrator Sheilah Beckett (1913-2013) was the first female artist hired to work at New York’s Charles E. Cooper Studio. Like various other illustrators of children’s books, Beckett also worked in advertising and greeting cards. She created art which sold wafers, chocolates and also advertisements for General Electric.

Sheilah Beckett never retired from illustration, and she moved with the times, switching to graphic design software as the times changed around her. (Note that she died at age 100!)

You may recognise Sheila Beckett’s work from Little Golden Books e.g. My Little Golden Christmas Book: Favorite Christmas Rhymes and Stories (1957) The Twelve Days Of Christmas: A Christmas Carol (1992).

Sheilah Beckett is a good reminder to us all: If you’ve always wanted to pursue a creative career but think you’re too old, you’re not!

It is certainly not realistic to hope that a majority of men, in the arts or in any other field, will soon see the light and find that it is in their own self-interest to grant complete equality to women, as some feminists optimistically assert, or to maintain that men themselves will soon realize that they are diminished by denying themselves access to traditionally “feminine” realms and emotional reactions. After all, there are few areas that are really “denied” to men, if the level of operations demanded be transcendent, responsible, or rewarding enough: men who have a need for “feminine” involvement with babies or children gain status as pediatricians or child psychologists, with a nurse (female) to do the more routine work; those who feel the urge for kitchen creativity may gain fame as master chefs; and of course, men who yearn to fulfill themselves through what are often termed “feminine” artistic interests can find themselves as painters or sculptors, rather than as volunteer museum aides or part-time ceramists, as their female counterparts so often end up doing; as far as scholarship is concerned, how many men would be willing to change their jobs as teachers and researchers for those of unpaid, part-time research assistants and typists as well as full-time nannies and domestic workers?

Linda Nochlin, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists, 1971

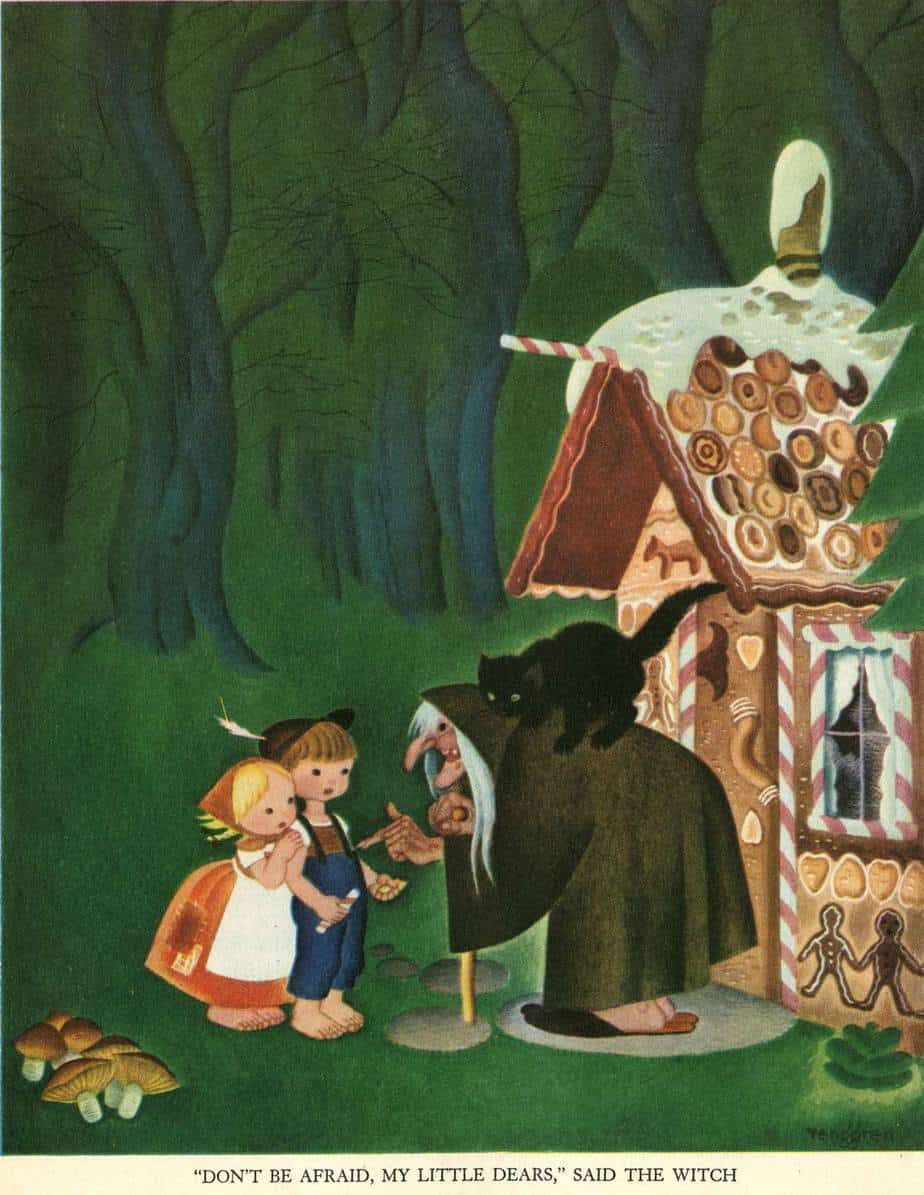

GUSTAF TENNEGREN

Gustaf Adolf Tenggren (1896 – 1970) was a very well-known Swedish American illustrator. He had a fairytale style influenced by Arthur Rackham, also very famous and distinctive. Tenggren’s work is easily recognisable due to the silhouetted figures and caricatured faces.

MARGARET TARRANT

Margaret Winifred Tarrant (1888 – 1959) was an English illustrator, and children’s author, specializing in depictions of fairy-like children and religious subjects. She began her career at the age of 20, and painted and published into the early 1950s.

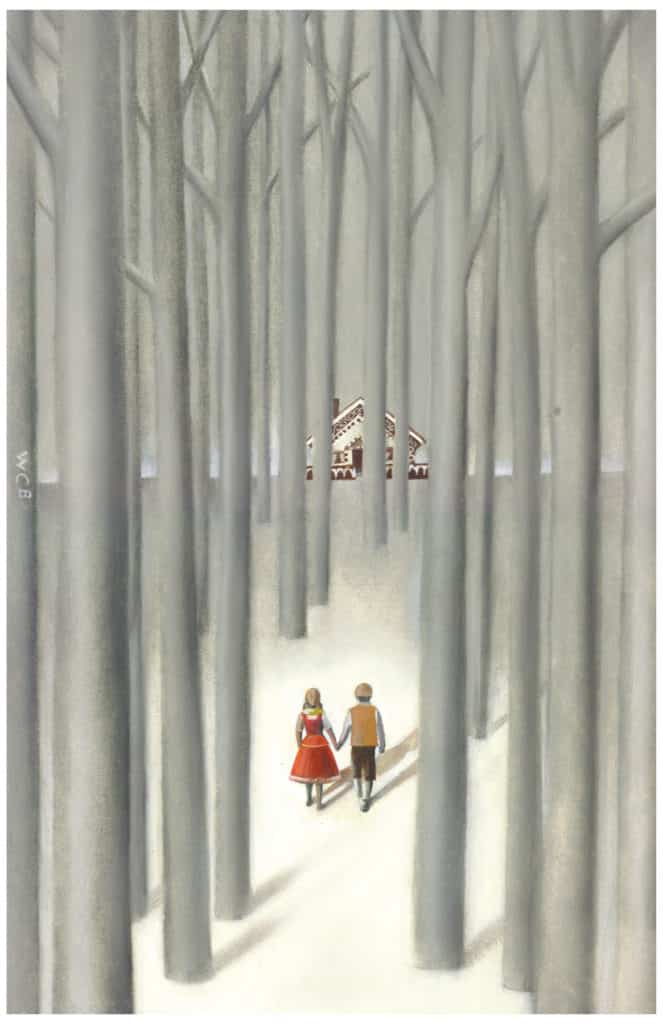

WAYNE BROWN

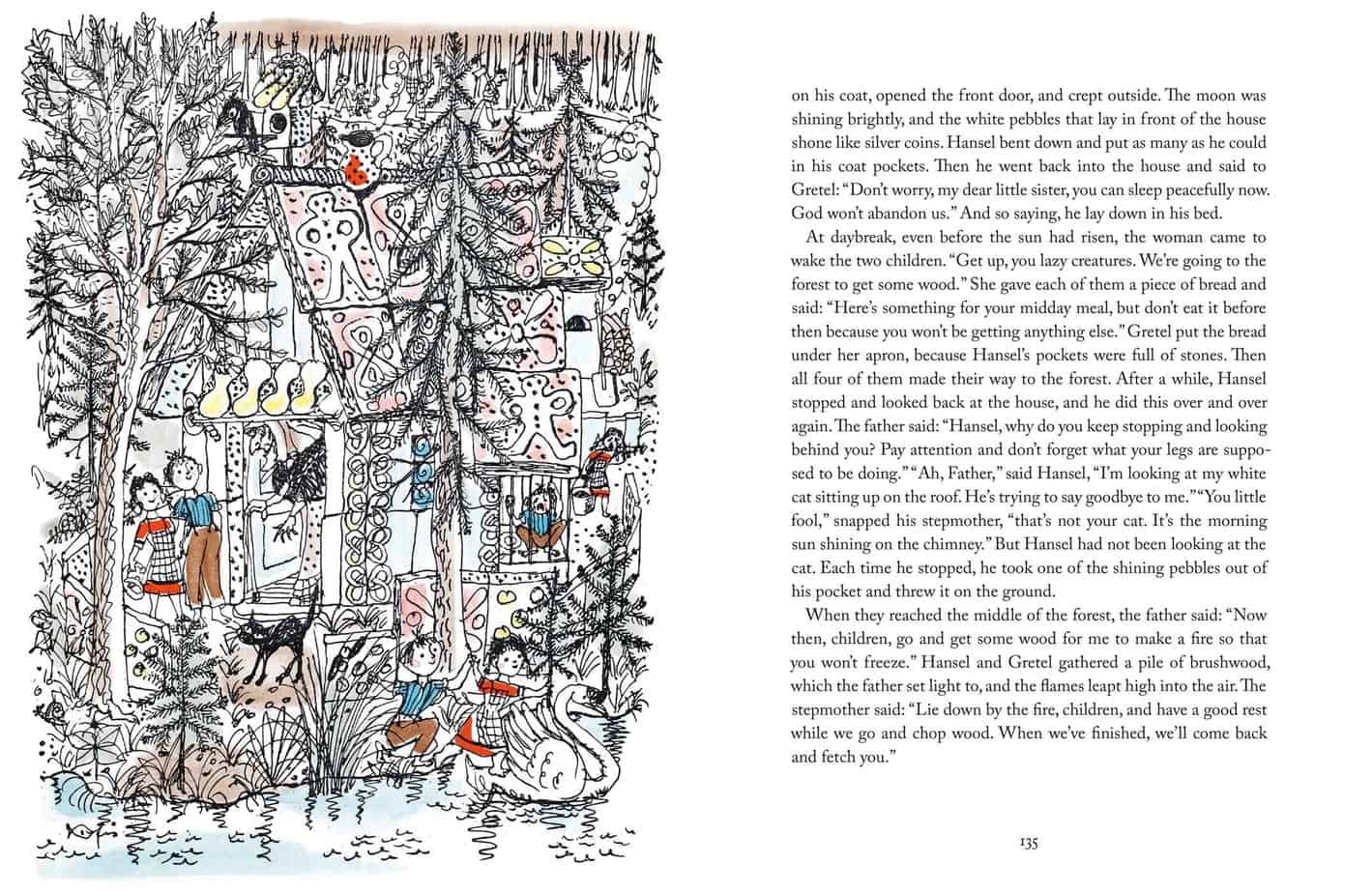

LORENZO MATTOTTI

This is a much more recent publication. I’ve covered it here. Neil Gaiman re-visioned the story and crafted a less sexist version than the usual, giving Gretel more agency.

This one looks almost like a photo which has had a Photoshop filter put on it. Look closer and you immediately see it’s not, but there’s a weird, unsettling realism about it. The light comes clearly from the moon filtering through trees, though Mattotti has surrounded the children — or the shadows of the children — with white as Wanda Gag did. The layout is also similar to that by Wanda Gag, with the children coming in from the right to a house positioned centre left.

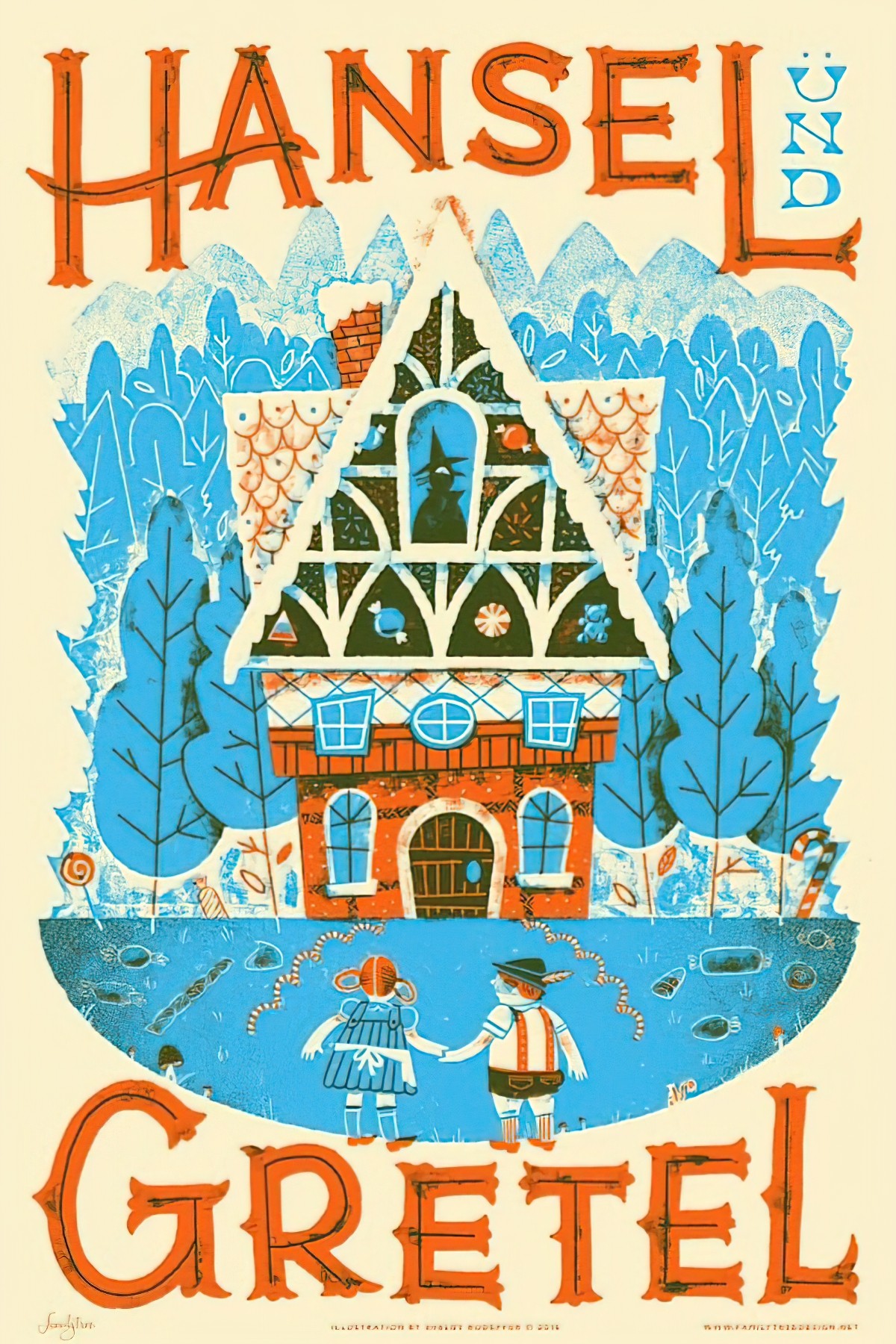

SHELBY RODEFFER

Rodeffer is an artist working today, in a style that harks back to the 1970s. This is a relatively symmetrical version of the gingerbread house. It doesn’t look all that much like food — it doesn’t make you want to lick the page, but the hints of sweets are there. (It would be hard to make this look tasty in this colour palette).

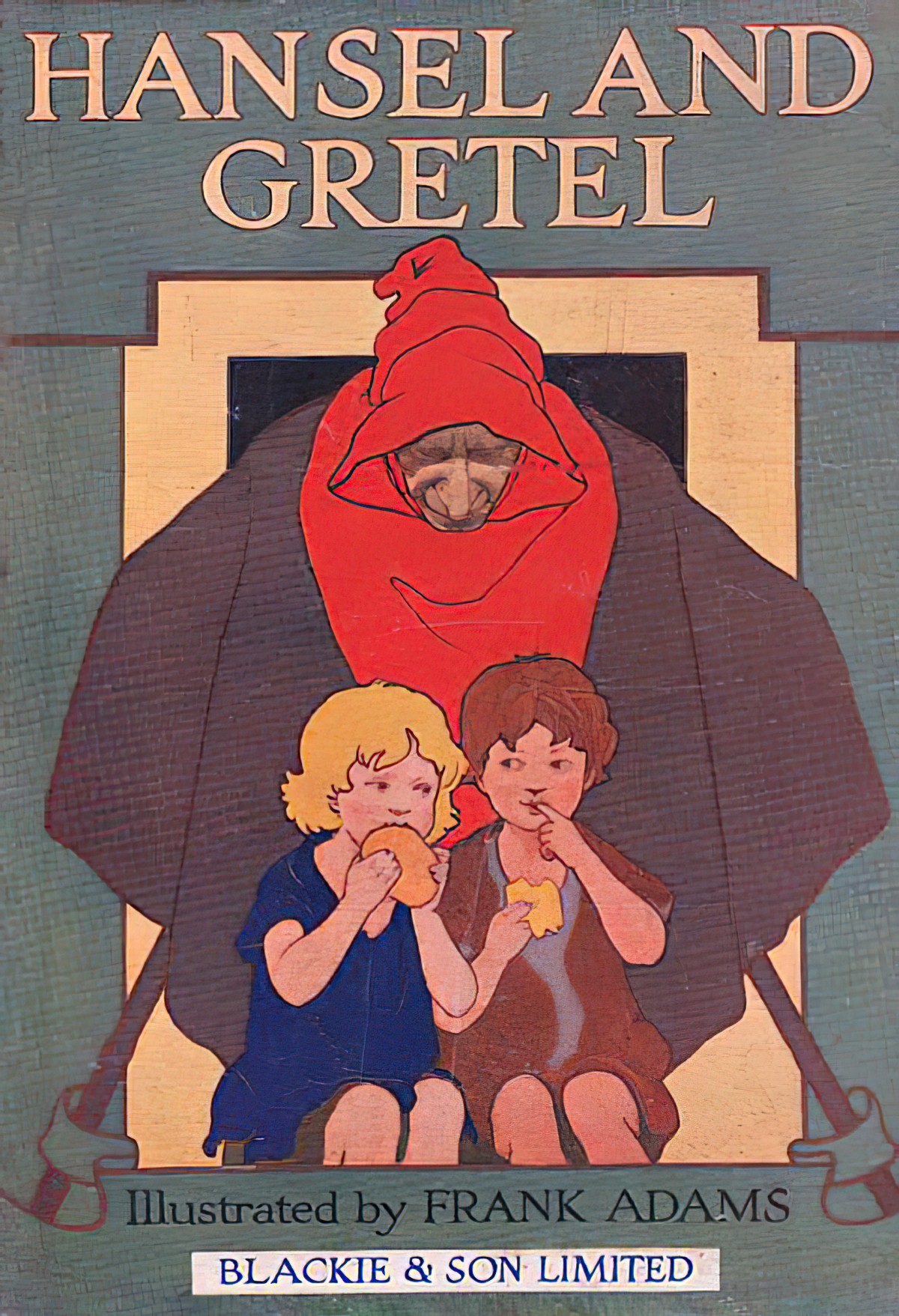

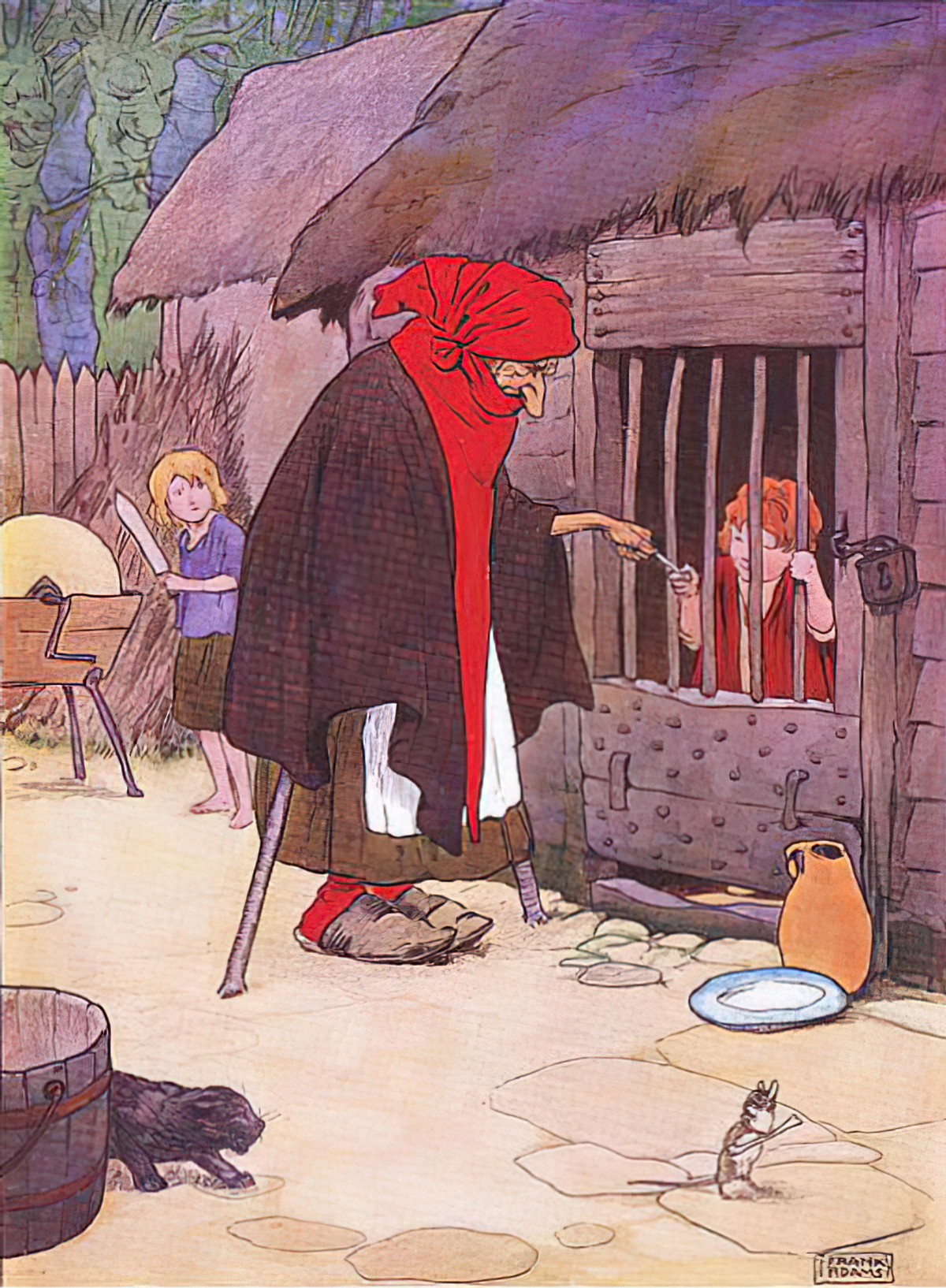

GINGERBREAD HOUSE BY FRANK ADAMS

This edition of Hansel and Gretel was published around 1941, with illustrations by American Frank Adams (1914 – 1987). Before he got into art, Adams was an engineering draftsman during World War 2.

The war was hugely influential for this artist, whose best-known work is for The Home Front, published 1944.

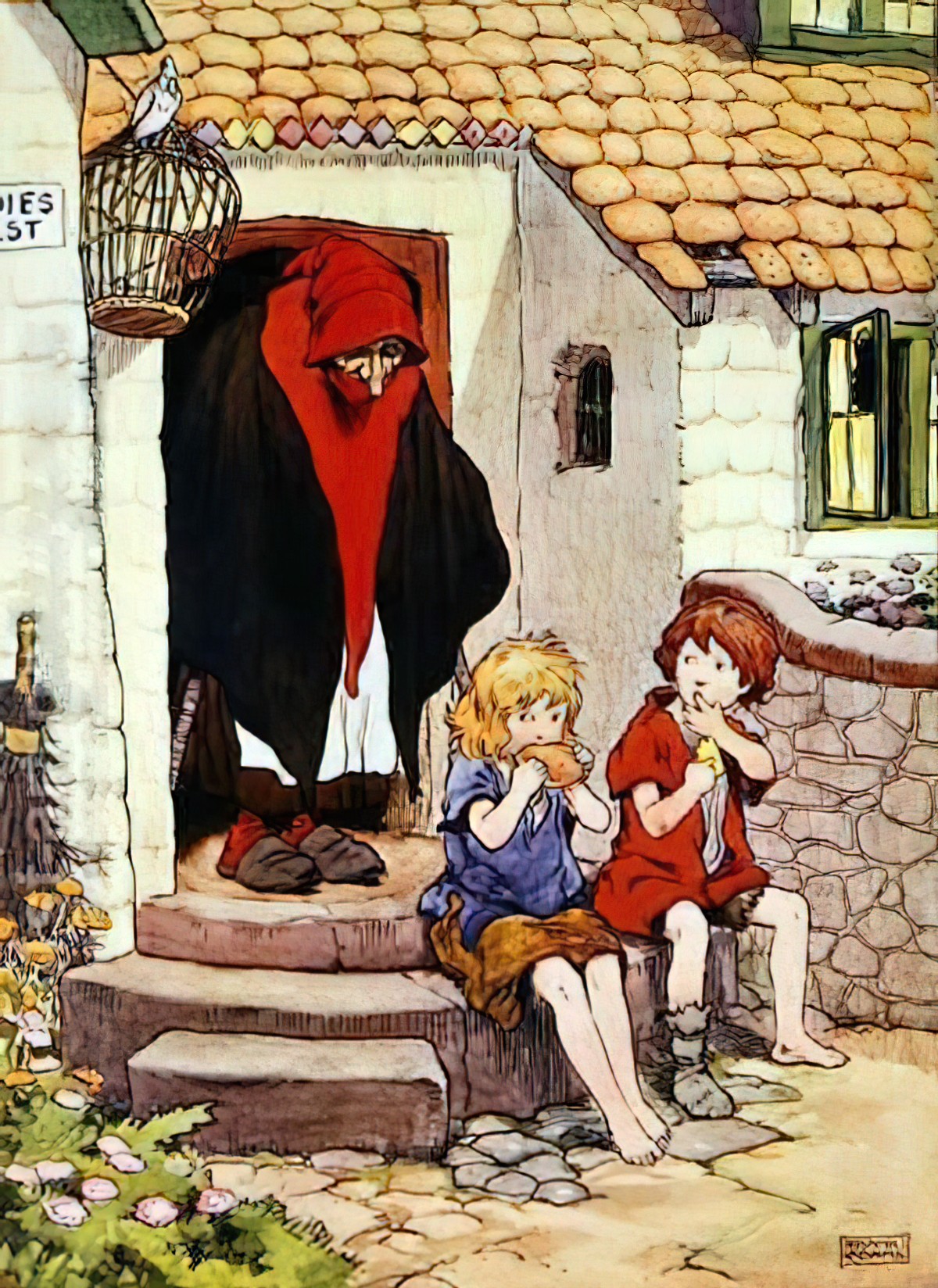

ANNE ANDERSON

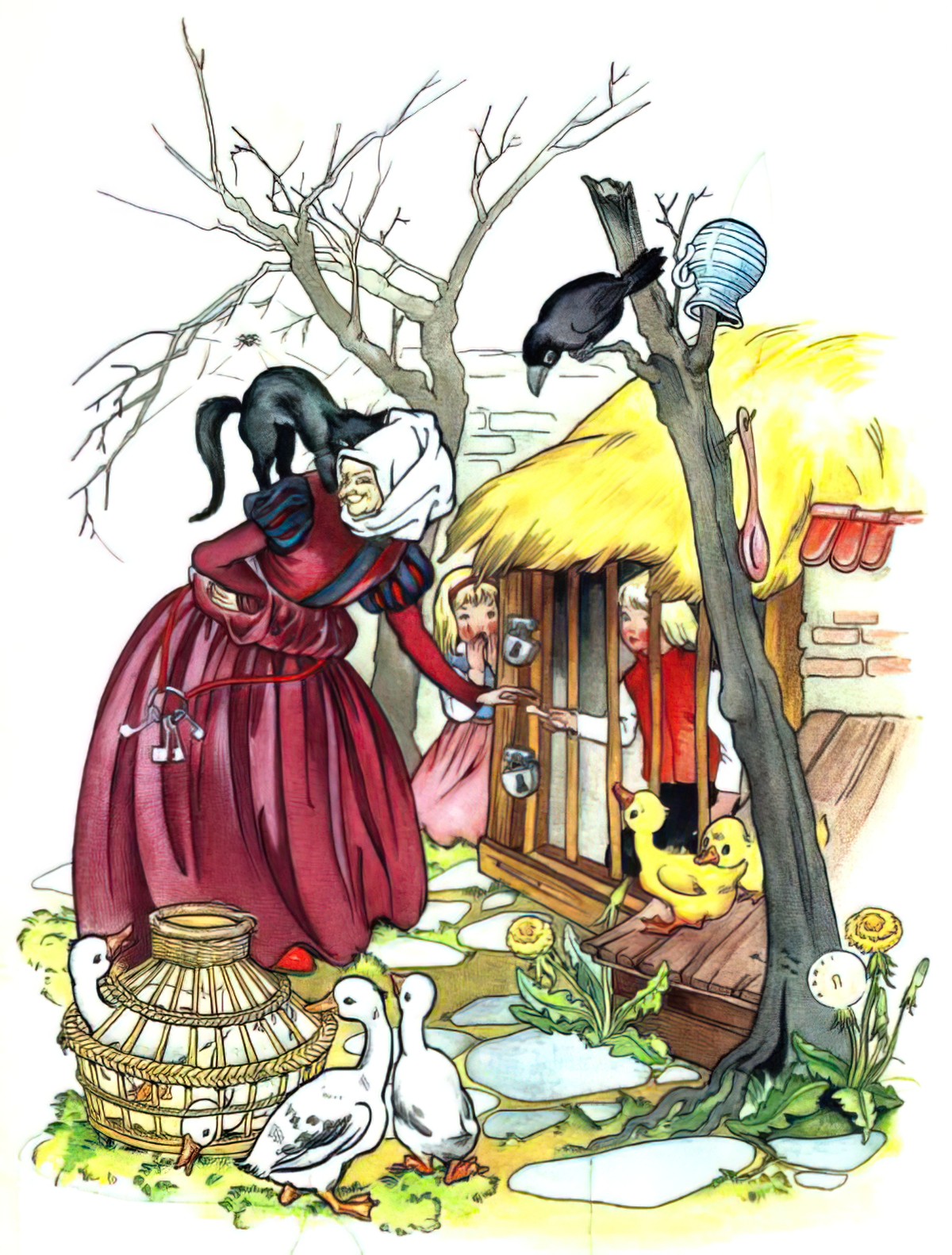

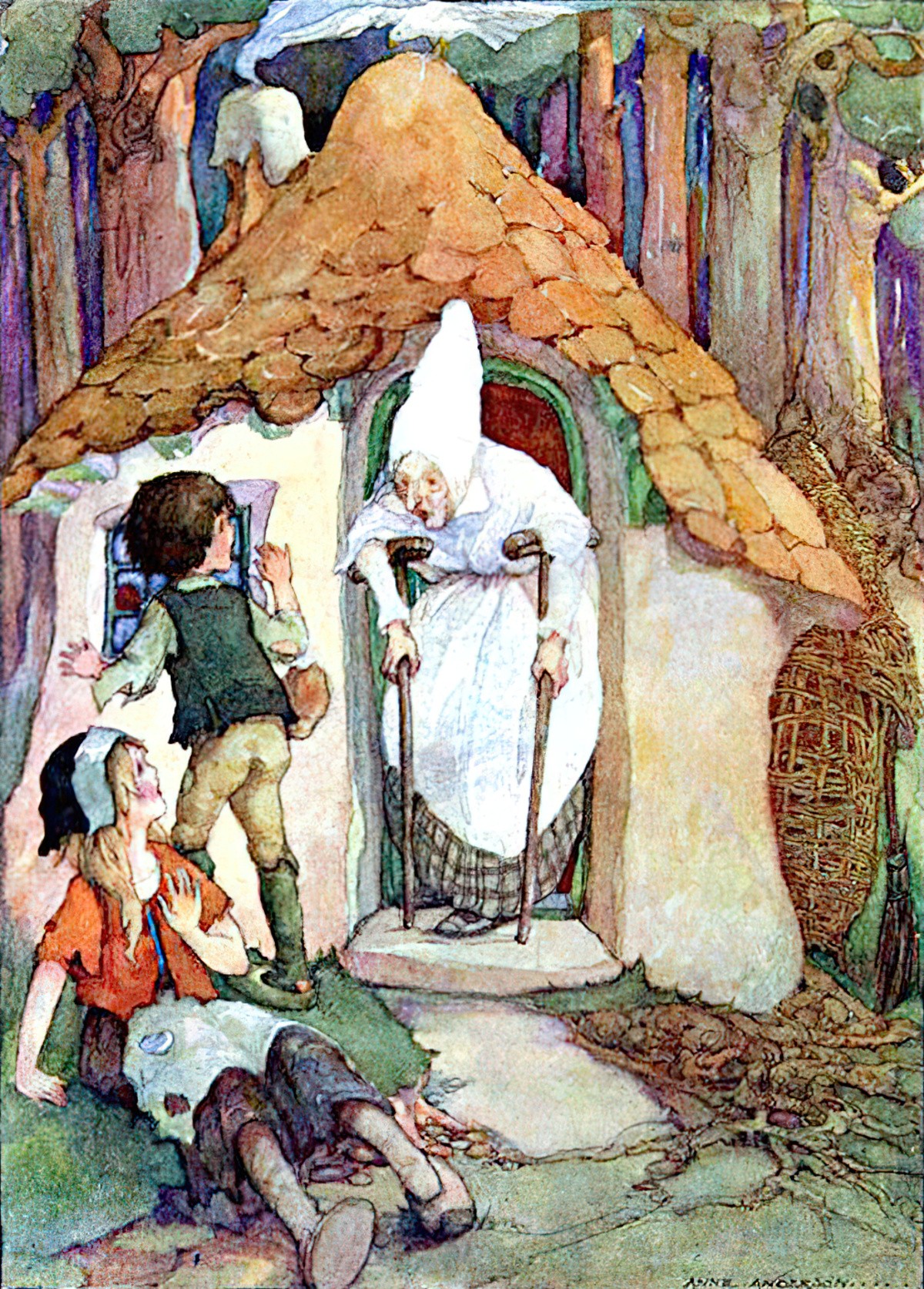

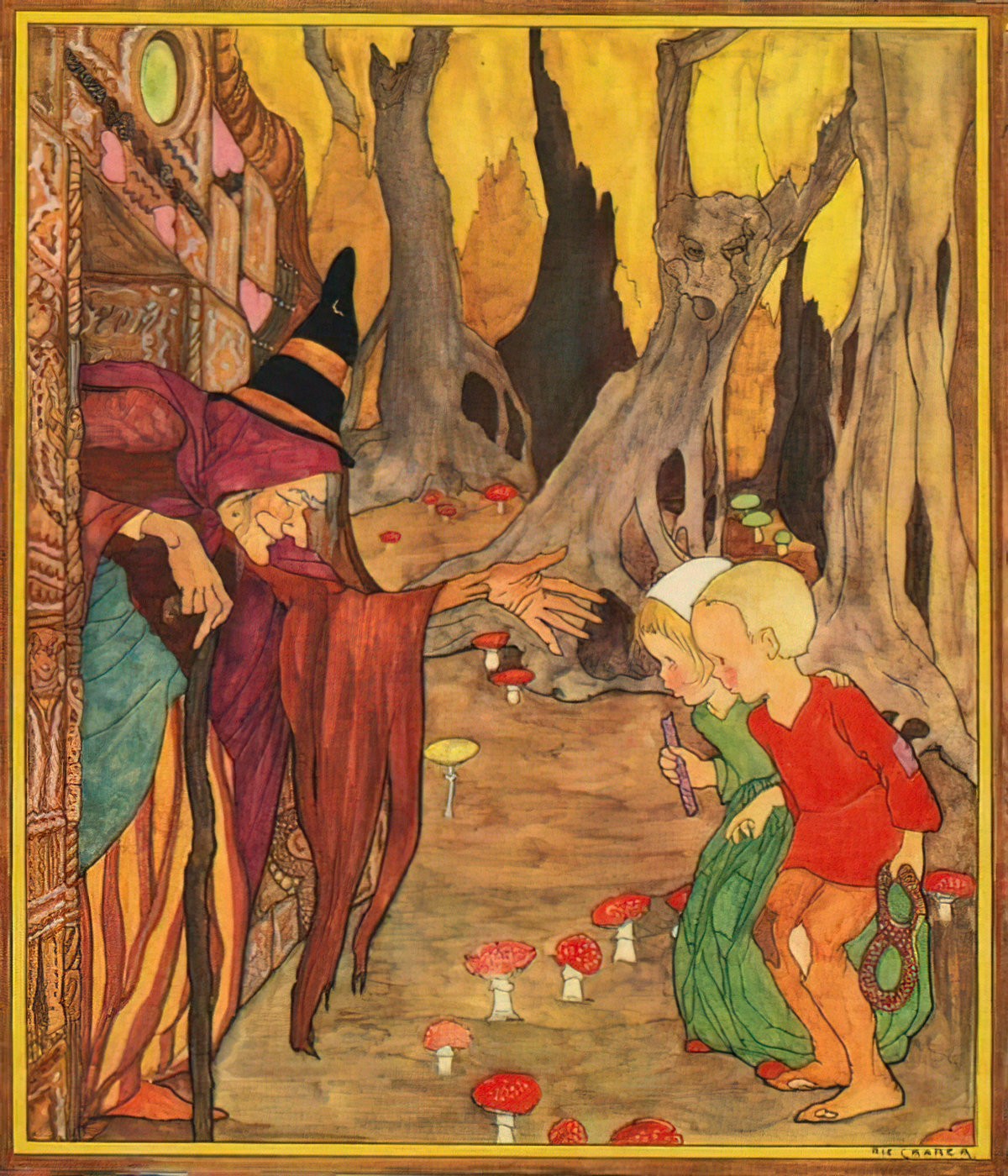

RIE CRAMER

Rie is short for Marie, who lived between 1887 and 1977. Born in the Dutch East Indies to a ship captain father, Cramer came back to the Netherlands and turned into a prolific Dutch illustrator. When commentators talk about the interwar period of illustration, they’re talking about the iconic work by Rie Cramer.

This artist was also a social activist. Some of her work was banned during WW2 for attacking National Socialism. So she wrote for an underground newspaper to get around the ban.

BILL BURGARD

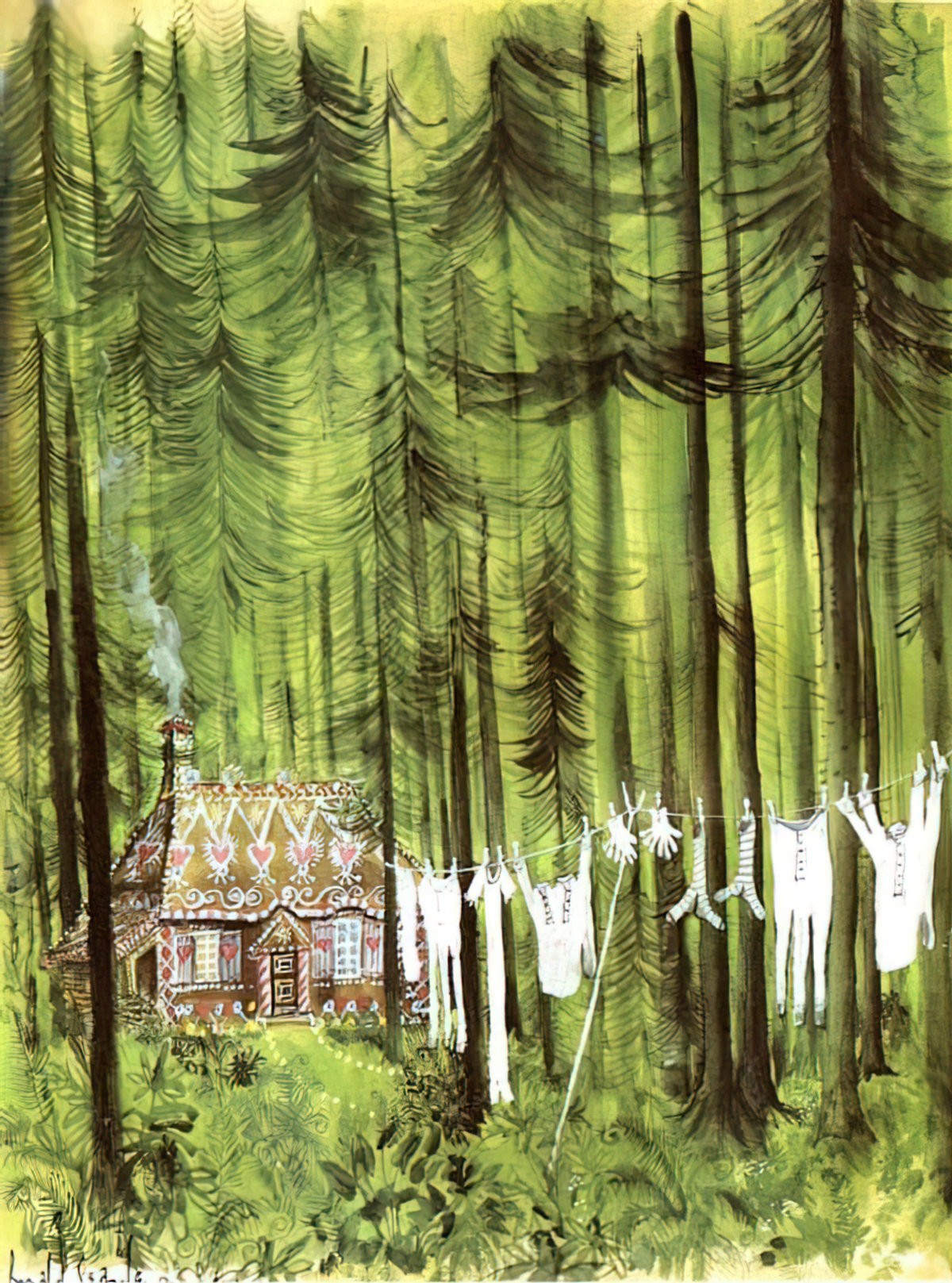

Bill Burgard foregrounded the creepy trees in this minimalist illustration. This is a forest with no life in it at all. There is a light source, coming from the bottom left. The house itself is almost in the centre of the layout… but not quite. These two aspects combined contribute to the uneasy, off-kilter atmosphere.

VARIOUS OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS OF HANSEL AND GRETEL’S GINGERBREAD HOUSE

Influenced by the mysterious place gingerbread holds in classic children’s stories–equal parts wholesome and uncanny, from the tantalizing witch’s house in “Hansel and Gretel” to the man-shaped confection who one day decides to run as fast as he can–beloved novelist Helen Oyeyemi invites readers into a delightful tale of a surprising family legacy, in which the inheritance is a recipe.

Perdita Lee may appear to be your average British schoolgirl; Harriet Lee may seem just a working mother trying to penetrate the school social hierarchy.

But there are signs that they might not be as normal as they think they are. For one thing, they share a gold-painted, seventh-floor walk-up apartment with some surprisingly verbal vegetation.

And then there’s the gingerbread they make. Londoners may find themselves able to take or leave it, but it’s very popular in Druhástrana, the far-away (and, according to Wikipedia, non-existent) land of Harriet Lee’s early youth.

In fact, the world’s truest lover of the Lee family gingerbread is Harriet’s charismatic childhood friend, Gretel Kercheval–a figure who seems to have had a hand in everything (good or bad) that has happened to Harriet since they met.

Decades later, when teenaged Perdita sets out to find her mother’s long-lost friend, it prompts a new telling of Harriet’s story. As the book follows the Lees through encounters with jealousy, ambition, family grudges, work, wealth, and real estate, gingerbread seems to be the one thing that reliably holds a constant value.

THE EDIBLE HOUSES TROPE

Edible houses predate Hansel and Gretel. “The Land of Cockayne” is a poem from a 14th century manuscript, Kildare Poems. This is Ireland’s earliest known literary text in (Middle) English. This particular poem is a satirical piece about a corrupt community of monks, who lead a life of fantastic luxury and dissipation in the mythical land of Cockaigne.

OTHER FOODSTUFFS

The gingerbread probably didn’t come into this German tale until its English translation.

- Schwankmärchen (Farcical tales) of Schlaraffenland (German): delicatessen products are on the roof

- Fabel de Cocaigne (French): fish, bacon, and sausages are on the roof

- Navicula sive speculum fatuorum by Geiler von Kaisersberg: Pfannkuchen (pancakes) on the roof

- The poem “Das Schlauraffenland” (1530) by Hans Sachens: Fladen (pancakes]) on the roof

- Wrozki by Podworzecki (1589) (Polish): sides of bacon and dumplings etc.

- Hänsel und Gretel: the witch’s house is built from bread, covered in cakes and the windows are made of clear sugar. (The text of Hänsel und Gretel is from various retellings from Hessen. Told by Henriette Dorothea Wild, 1793 – 1867).

Note: the house is made of bread, the roof is decked with cake and the windows were made of clear sugar (hellem Zucker). “Gingerbread” probably came from an English translation.