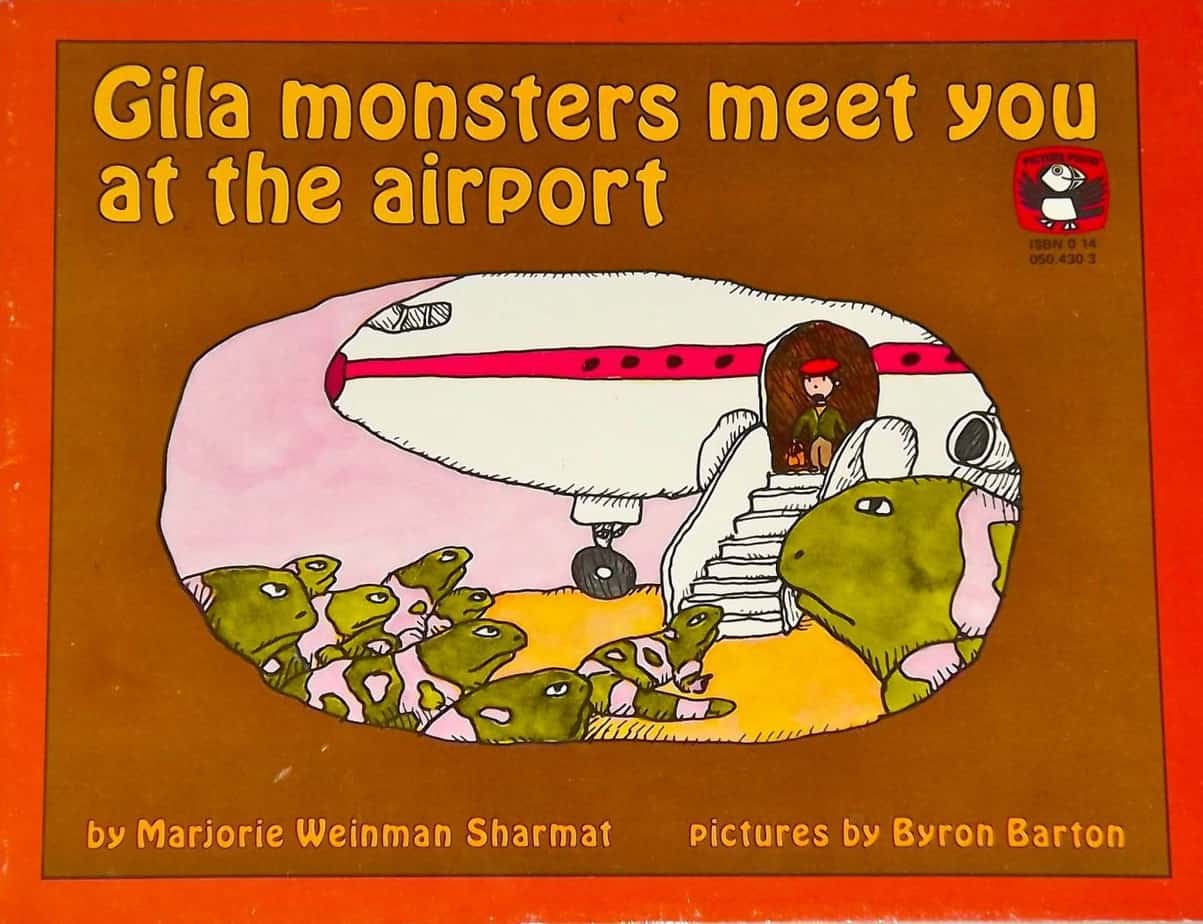

Gila Monsters Meet You at the Airport (1980) is an American picture book written by Marjorie Weinman Sharmat and illustrated by Byron Barton. This story teaches the young reader to recognise a regional stereotype, and to question its veracity. This story was chosen for the first season of Reading Rainbow.

I had to look up the meaning of gila monster:

A heavy, typically slow-moving lizard, up to 60 cm (2.0 ft) long, the Gila monster is the only venomous lizard native to the United States and one of only two known species of venomous lizards in North America, the other being its close relative, the Mexican beaded lizard (H. horridum).

Wikipedia

SETTING OF GILA MONSTERS MEET YOU AT THE AIRPORT

“I live at 165 East 95th Street…”

It’s rare to encounter an actual address specified in fiction. If you check it out on Google Street View you’ll see it’s an apartment block in Brownsville on a beautiful leafy street and there’s a fenced park opposite, perfect for kids. (The price of real estate there may not be so perfect for parents with kids…)

- PERIOD — I’m not in the best position to understand this book because I’m not American, and even if I were, I’m a little too young to remember the childhood mythology surrounding the East and West coasts of America back in 1980.

- DURATION — a few months

- LOCATION — This is a story that could only take place in America because the entire plot is about American regional stereotypes, though a similar book could be written almost anywhere, using different examples. An Australian book would explore the coastal/inland divide. A New Zealand example might be the North and South Islands.

- MANMADE SPACES — New York City and the suburbs

- NATURAL SETTINGS — The natural settings of this stories are imaginative but still very real to the character.

- WEATHER —

- TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY — Aeroplanes, if only for the title.

- LEVEL OF CONFLICT — This is about how people from different regions, even within the same country, can be so wrong about each other.

- THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE — The main character, and his mirror image, are both very wrong about each other’s natural environment and they’re about to find out the truth, which is more boring (and more safe) than the landscapes of their minds.

STORY STRUCTURE OF GILA MONSTERS MEET YOU AT THE AIRPORT

Many picture books are shaped like a mirror image, or as I prefer to think of it, like one of those butterfly paintings in which kids dab paint over one half, then fold the paper to create the symmetrical wings.

In picture books, the main character will often spend one half of the story doing or thinking one thing, then the second half doing or thinking the inverse.

- In Sidewalk Flowers, the girl spends the first half of the story collecting flowers, and the second half giving them away.

- In The Gruffalo, the mouse meets each character in the woods and describes a fantasy chimera designed to scare away beasts who eat mice. After meeting an actual Gruffalo, the second half of the book the mouse meets all the same characters again, this time scaring them. This is very similar to what Roald Dahl did with The Great Big Enormous Crocodile.

- In Wolf In The Snow, the girl spends the first half of the story looking for a lost wolf pup’s pack. After the turnaround, she becomes the lost ‘wolf pup’ and now it’s the wolves’ turn to help her find her parents.

Here, the boy will spend the first half of the story thinking about ‘Out West’ in terms of cowboy stereotypes, and the second half learning the veridical reality of his new home. This creates a parallactic effect, beloved of the literary Impressionists, in which the reader is given two (or more) different perspectives and invited to choose which details to take as ‘true’.

The Impressionists thought that there was no such thing as ‘the truth’, only different versions of it. Do you think that’s what’s going on here, or is the reader invited to take away the truth of New York vs Out West? Might illustrations help with that?

PARATEXT

“I live at 165 East 95th Street, and I’m going to stay here forever,” says the young hero firmly. After all, out West nobody plays baseball because they’re too busy chasing buffaloes, and you have to ride a horse to school even if you don’t know how, and you can’t sit down because of the cactus. But his parents are moving West, and they say he has to go, too. Once there, however, the boy doesn’t meet the Gila monsters he expected. And on the ride to his new home (by taxi, not horse) he discovers the West is neither as different nor as bad as he’d imagined.

Marjorie Weinman Sharmat and Byron Barton share a keen sense of the ridiculous and a compassionate understanding of a child’s anxieties. Together they have created a perceptive, exuberantly funny picture book that will have children in all parts of the country laughing away their own fears about new experiences.

MARKETING COPY

SHORTCOMING

The first person narrator doesn’t want to move, but like any child anywhere, he doesn’t have a choice. He is wrong about the Old West and has clearly been influenced by cowboy movies and the mythology of Western expansionism. The following is ironically funny:

The desert is so hot you can collapse, and then the buzzards circle overhead, but no one rescues you because it’s real life and not the movies.

DESIRE

This is a classic example of a main character who wants everything to stay the same, but things are changing around him. He tells us he would like to stay in New York and eat salami sandwiches with his best friend Seymour. Notice how these details are beautifully specific.

OPPONENT

Although Seymour is the narrator’s best friend, Seymour is engaging in the tradition of tall stories when he warns the narrator that when he arrives Out West gila monsters will be there to meet him at the airport.

This gila monster is the imaginary Minotaur opponent who turns out to be no such thing. Monsters who are imaginatively terrifying then turn out to be no such thing are common in picture books.

PLAN

The narrator has no plan; the opponent has a plan, though. Seymour is telling his friend, who is moving, all these stories about Out West to scare him, possibly hoping he won’t leave.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

The threat of the gila monsters is revealed to be an anticlimax when the narrator steps off the plane and doesn’t see any, admitting that he doesn’t know what they look like. The reader can also see from the illustration that this is a regular, realistic airport. This contrasts with the tantalising cover image, in which gila monsters do, in fact, meet passengers coming off the plane.

ANAGNORISIS

At the airport, the narrator meets a boy who looks like his friend Seymour back in New York. Are we really to believe he looks like Seymour? That’d be a coincidence. Let’s read it symbolically. The narrator expected to find people so completely different from himself that this guy looks remarkably familiar.

I see a boy in a cowboy hat.

He looks like Seymour, but I know his name is Tex.

“Hi,” I say.

“Hi,” he says. “I’m moving East.”

“Great!” I say.

This marks the turning point. Now the boy will recount all of the incorrect things he has heard about New York.

When the narrator takes the taxi with his parents to his new house Out West, he is astonished to find familiarity: boys playing baseball, a familiar chain restaurant, boys on bikes.

The last three scenes are a masterclass in concise character arc.

- He notices things are similar Out West as back home. (Arc: He’s seeing similarities rather than difference.)

- He hopes one of the boys on the bike is named Slim. (Arc: a newfound enthusiasm for the different.)

- He realises on the final page that Seymour has been pulling his leg or is easily duped. As is the rule in non-experimental narrative, Seymour’s mask (as a trickster) has come off.

NEW SITUATION

The narrator has become the trickster, in a final reversal of roles.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

This kid is adaptable and will soon make friends in his new home.

RESONANCE

I don’t know if the mythologies of this book persist, and hadn’t even heard of a gila monster. However, I’m constantly surprised that here in Australia the same stupid stories and rhymes have been passed down through the ages and my kid brings them home, thinking I won’t have heard them… 30 years ago (in a neighbouring country). So I’m guessing this book will resonate with modern American kids. Even if the mythology has changed, there’s plenty for discussion in here, because stereotypes never die.

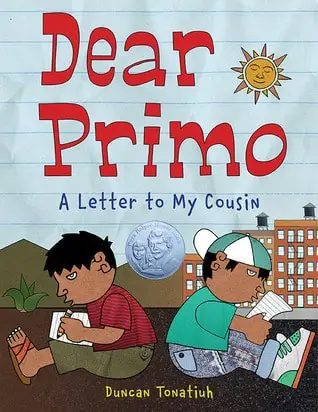

From first-time Mexican author and illustrator Duncan Tonatiuh comes the story of two cousins, one in America and one in Mexico, and how their daily lives are different yet similar. Charlie takes the subway to school; Carlitos rides his bike. Charlie plays in fallen leaves; Carlitos plays among the local cacti. Dear Primo covers the sights, sounds, smells, and tastes of two very different childhoods, while also emphasizing how alike Charlie and Carlitos are at heart.

Cara chats remotely with Dr. Christie Wilcox, a conservation biologist and science writer. They focus on the topic of her new book, “Venomous,” including the difference between venom and poison, the vast number of animals that have evolved venom as a predation or defensive mechanism, and how the toxins in venom are being used in modern medicine to treat a variety of diseases.