Stories that scare me the most often involve getting lost. The scariest Australian stories are, to me, the ones where a little boy goes out into the wilderness and dies in the heat, unable to find his house.

In one standout example, the little boy hasn’t left his parents’ own property — what’s known as a ‘station’ in this country. I have a friend who grew up until the age of ten on an Australian inland station which is bigger by sheer landmass than certain small countries. Getting lost and dying on your very own property is a terrifying prospect.

Below, John Scheckter talks about the popularity of ‘injected characters’ in Australian fiction, a term more commonly known as ‘fish out of water stories’ in Hollywood:

The narrative device of injecting an innocent or nearly defenseless character into an alien environment is common. Scott, Cooper, Conrad, for example, frequently depict characters whose viewpoints and values change as they move deeper into a primitive landscape. Though innocent with regard to what they encounter, these characters are usually rather mature when they are injected into the new territory. They represent more or less finished and educated individuals, according to the codes of the societies they leave. The encounter, then, occurs between the values of the old society and those of the new environment.

Injected characters appear frequently in Australian fiction, usually as English visitors or colonists who begin with the naive assumption that Australia will be just like home. But the assertion of Australian nationalism requires more than this narrative use of mature characters.

The economic, political, and cultural institutions of nineteenth-century Australia bore a strong stamp of colonialism, strong enough in many cases to allow British attitudes to survive nearly unchanged. The land at first made few repulses of whatever was impressed upon it, the interior was found out too late to alter the momentum of English establishment, no other nation competed with England’s authority, and the economic structure of imperialism dominated from the start; none of these factors provided for cultural independence. Thus, although many Australian novelists use the technique of character injection to play off English values, they generally follow the European pattern for using it. The Australian bush takes its cues from the country town, the town from the coastal city, and the city from London. The contrasts pointed out by the technique tend to become stock, their terms commonplace, and their conclusions foregone.

There is a kind of character injection, however, that may be called an indigenous Australian myth: the story of the child lost in the bush. Analogues of this plot exist in European fairy tales, but it has more to do with the real landscape of Australia, or with the perceived possibilities of landscape. The lost child is a political story, too. Australians have often seen themselves as orphans or outcast children of Europe, given inheritances to which they must respond, for which they must pay, often without reason or reward. What is especially interesting, and especially Australian, about such stories is that they become archetypes of national determination. Since the character is genuinely innocent, having no basic form or preordained personality, the author can, in structuring his story, freely load it with national symbolism. The characterization of the child, his fate, and the reactions of the adults who search for him raise the fairy tale to the level of myth.

THE LOST CHILD IN AUSTRALIAN FICTION Modern Fiction Studies, Vol. 27, No. 1, SPECIAL ISSUE: MODERN NEW ZEALAND & AUSTRALIAN FICTION (Spring 1981), pp. 61-72 (12 pages)

Next, John Scheckter explains the basic structure of an Australian ‘Lost Child’ story:

A LOST CHILD STORY

- A young child is attracted by land he sees in the distnace.

- He sets off from home in an unfamiliar direction.

- At first he plays happily.

- He grows hungry or tired.

- He begins to panic.

- Adult searchers find the child.

- It is (usually) too late to save him.

MISSING IN AUSTRALIA

If you haven’t yet watched Last Stop Larrimah (2023), based on a book and produced by American duo The Duplass Brothers, do check that out. Many people go missing in Australia each year. In The Outback, it doesn’t take a genius mastermind to hide a body, if you know what you’re doing and the police are insufficiently canny/proximal.

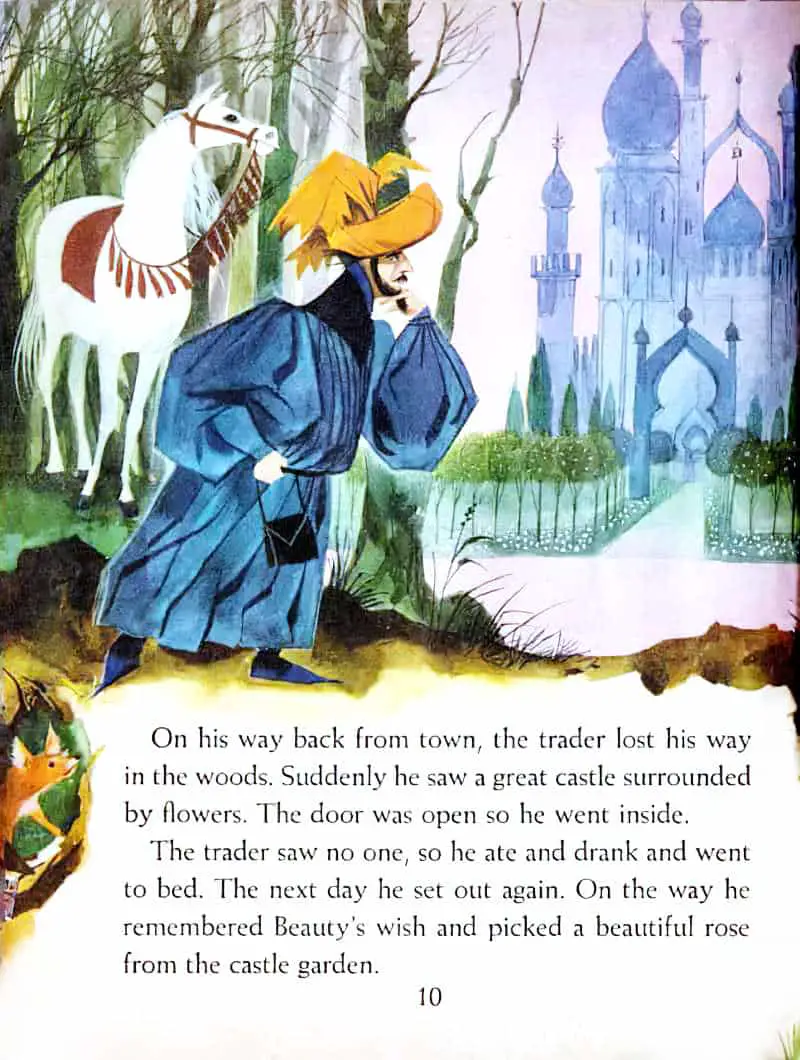

GETTING LOST IN VERY OLD STORIES

Hansel and Gretel is the OG European fairy tale about getting lost.

But this story is built on a much deeper and more ancient tradition in which the hero leaves home and becomes psychologically ‘lost’. In many cases, they are lost because they are wearing some kind of mask. They are not being true to their ‘true selves’. The hero faces many opponents, also maybe an ally, finally defeats the Minotaur and returns home. Or finds a new one. The labyrinth is the symbolic representation for being on a massive journey and getting lost.

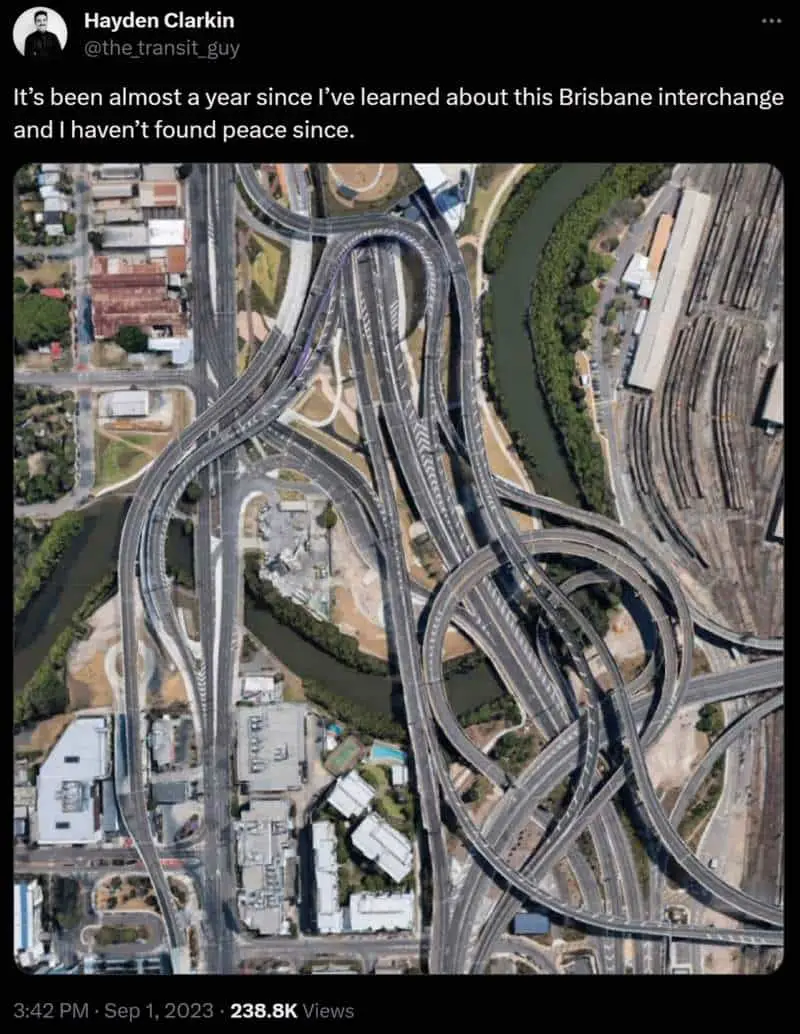

THE HISTORY OF HUMAN NAVIGATION

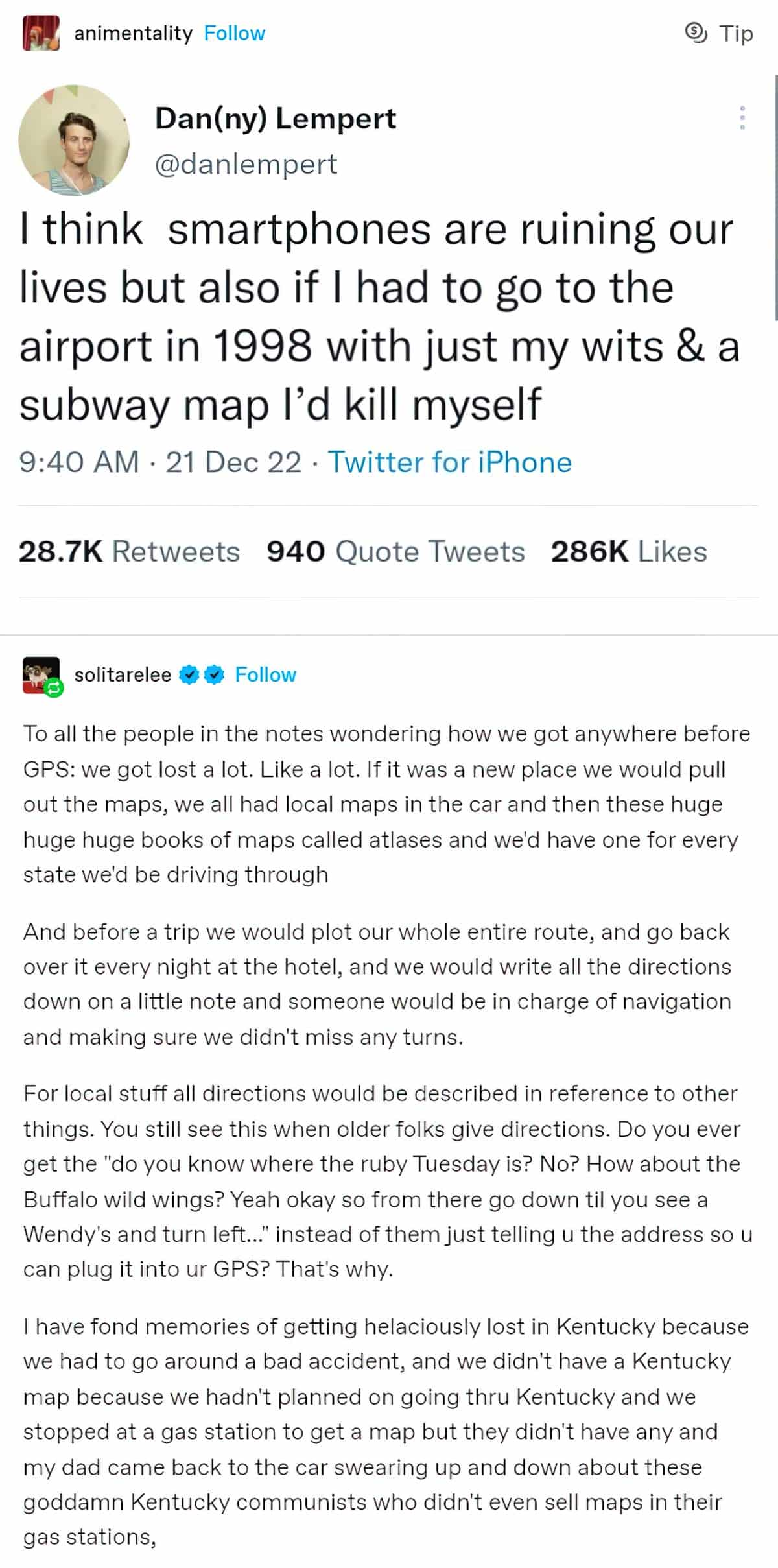

As someone who has no navigation skills whatsoever and who relies on GPS apps to take me from one location to the next even when I know the route, I find it hard to fathom how I ever got by without it. And I have been driving for longer than I’ve had access to GPS — by about a decade. For about a decade, I would look at a map book before leaving the house. I’d try to memorise the route. Usually I couldn’t remember the entire thing, and I’d make a few wrong turns before getting to the exact place I wanted. These days, GPS takes me straight there, though I do still have an issue with finding the entrance to places. This may sound ridiculous, but in a city like Canberra it’s very easily done, as there are bylaws against signage, and buildings are spread out. Moreover, streets have been designed as a curvilinear system rather than as the compact grid familiar to most city-dwellers around the world, so if you do think, “Bugger it, I’ll park here and walk to the entrance, wherever it is,” you’ll find yourself walking for a good half hour. In the heat of summer, that’s taxing.

Given my navigation difficulties, I stand in awe of our explorer ancestors who would not only work out how to get from hut to hut through the forest, but who built water-tight vessels and navigated between landmasses. Of course, we don’t hear about all the humans who tried and failed at this venture, but the ones who made it must have been outright geniuses.

Archaeologist David Wengrow explains:

Human populations [found] their way through island landscapes to remote places out in the middle of the Pacific. Of course they’ve got to have a superb grasp, practically and intellectually, of topography and the behaviour of the seas. You see it reflected in monumental architecture from very early periods which is often laid out in very precise alignments in relation to other monuments, in relation to the solstices. Here in the UK we have famously Stonehenge. People were clearly more than capable of developing very complicated mathematical and geometrical understandings in different ways to the way we do it now.

The most famous discussion of this was a book in the 1960s by Claud Levi Strauss, where he basically tried to suggest that there are two different forms of science:

There’s our notion of science which begins in the laboratory. So you carve out an artificial environment. You have men in coats or whatever, trying to generate new ideas and theories which are then applied to the world.

He contrasted that with the way most human discovery throughout the history of our species has actually taken place, which is a world of discovery in which there are no laboratories. Discovery is part and parcel of social life. It’s out there in the landscape, in people’s interactions with plants and animals. It’s applied from the beginning, and that presumably is how all those early systems of navigation, monumental construction, metallurgy, all of these things were discovered and generated through other systems of knowledge than the one that we’re familiar with, which is kind of intriguing in itself.

Downstream: Everything We Think We Know About Human History Is Wrong with archaeologist David Wengrow, Novara Media podcast, Wednesday 7 December 2022

LITERARY SYMBOLS AROUND GETTING LOST

The psychological state of being lost is, in fairy tales especially, closely associated with the forest. Darkness is key.

Ancient Greeks gifted us the labyrinth; in other stories metaphors around getting lost involve trips to the underworld.

In modern stories the labyrinth, underworld or forest might be transmuted as the city e.g. in Studio Ghibli’s The Cat Returns.

Occasionally it’s a desert, in which the blinding brightness itself functions as a kind of darkness.

Darkness surely speaks to some primal fear in us. Today, the only real way to get lost forever is to leave civilisation (or lose your phone).

The film Deliverance is about characters from the city who don’t know how to navigate the perils of the river and forest, approaching it recreationally. The fear in that story: You go to an unknown neck of the woods and meet locals who don’t want you there.

Note that the author of Deliverance visited Appalachia and the locals were very kind and friendly to him. Being an imaginative writer, he got to wondering what would’ve happened to him if the locals hadn’t been kind and friendly, as he relied on their help at one point to make it out of there.

Deliverance is the non-favour he delivered to the people of Appalachia, first a short novel, later a classic film.

THE PERILS OF SHORTCUTS

Horror stories about characters who take short cuts and pay a hefty price must play into our morality around ‘working hard‘, because in stories, short cuts are rarely rewarded.

Stephen King’s short story “Children of the Corn” features a couple who ‘get lost’ while driving the linear path between one part of the USA to another. You’d wonder how it’s possible to get lost on that highway, but King shows us how. The couple have become morally lost.

The Ritual (2017) is a classic example of men who try to take a shortcut through the forest and who end up meeting a hideous creature and a cult of dangerous outcasts.

Road Trip Stories in general punish characters from deviating off the set path, but there can be no clear winners, because when characters do obediently stick to the set path, they are punished for doing that. As much as we are punished for taking risks in life, we also live constricted lives by failing to forge our own path.

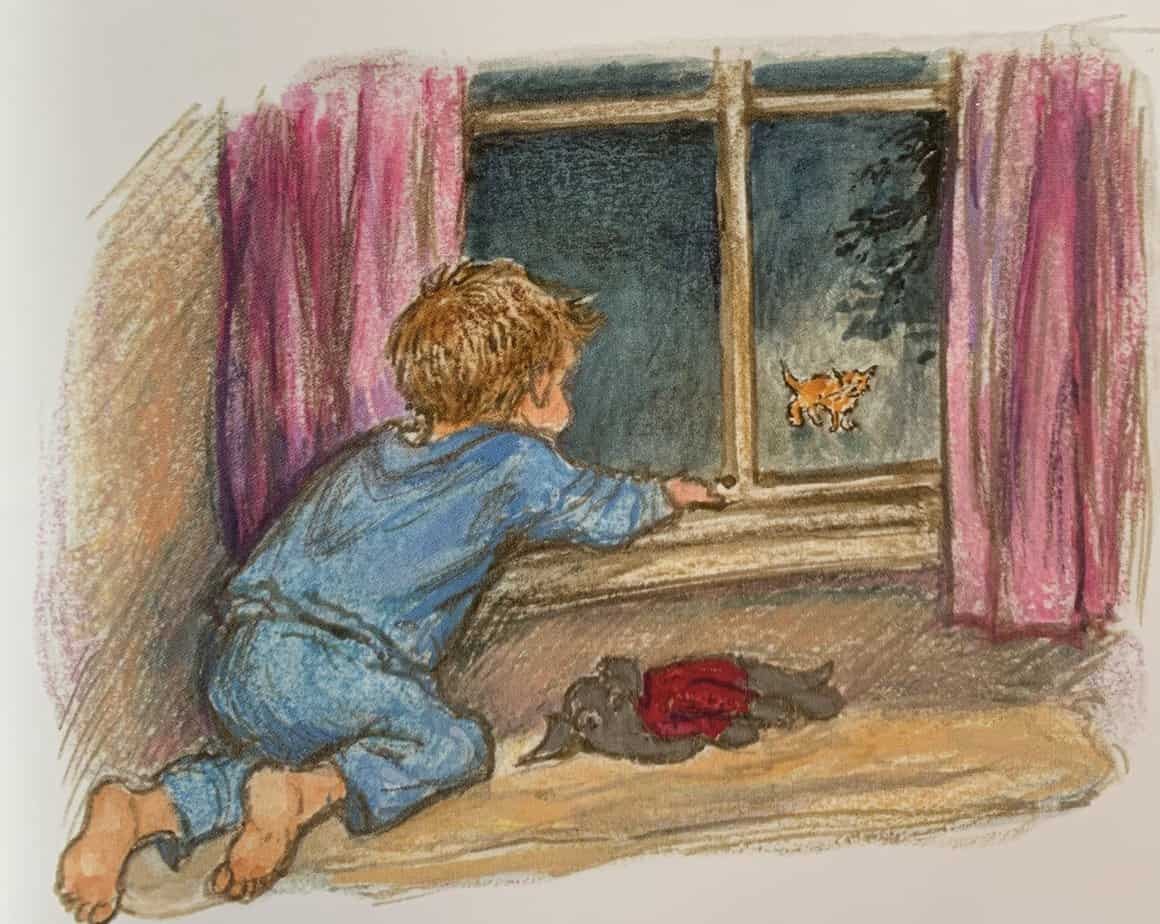

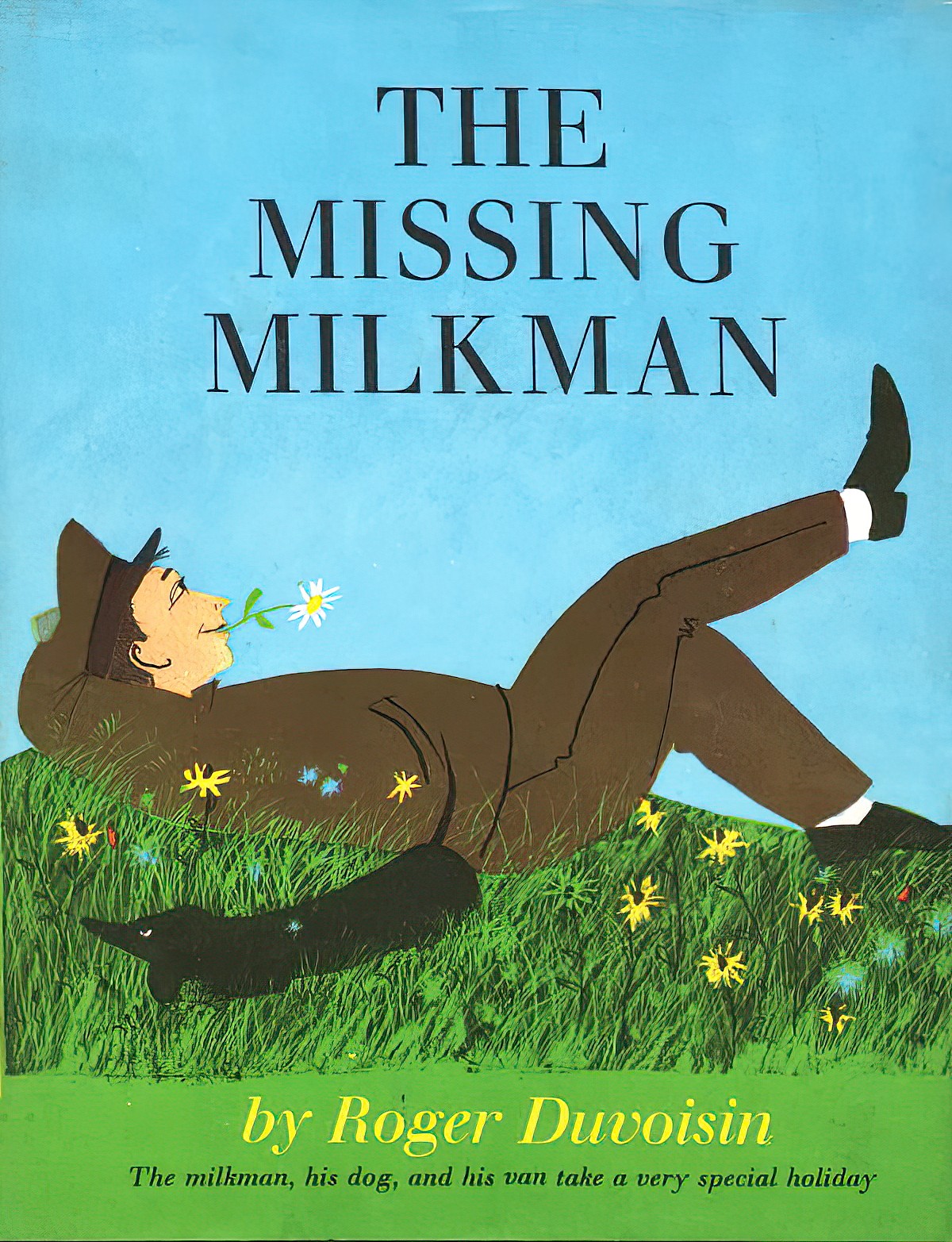

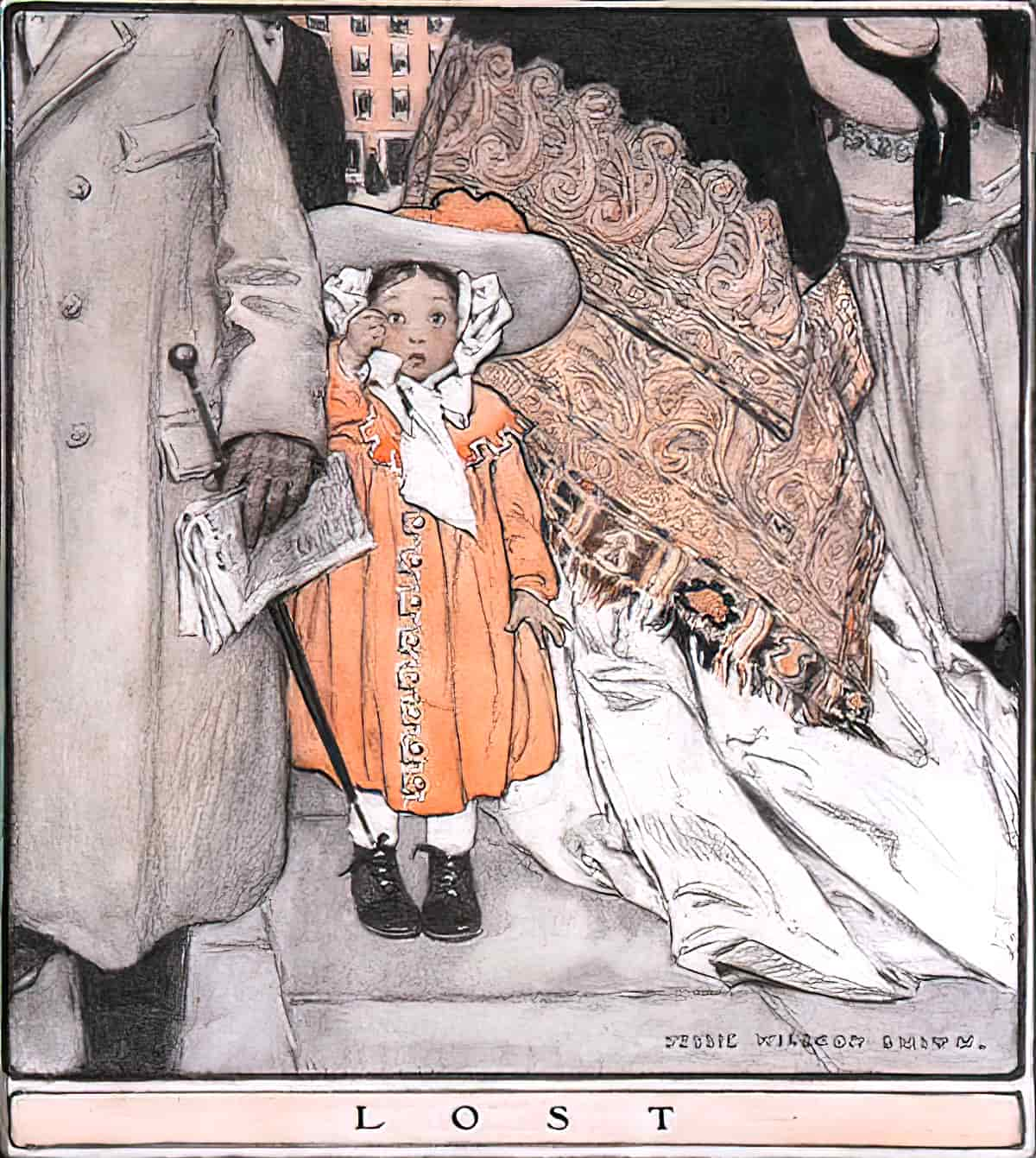

Picturebooks In Which A Character Gets Lost

Although getting lost is super scary, picture book storytellers don’t shy away from it. This is picture book bibliotherapy. For a young child, it’s very easy to get lost.

- Bob and Joss Get Lost and Bob and Joss Take A Hike by Peter McCleery, illustrated by Vin Vogal

- Sheila Rae, the Brave by Kevin Henkes

- Wolf In The Snow, a wordless book by Matthew Cordell, winner of the 2018 Caldecott medal

- Too Noisy written by Malachy Doyle, illustrated by Ed Vere. Like many picture books, this story conveys the message that home is the best place to be, even if there are problems with it (in this case, home is too noisy).

- The Shortcut

- This Moose Belongs To Me by Oliver Jeffers

- Where Is Home, Little Pip?

- Journey by Aaron Becker

Another fear: Your beloved pet will get lost.

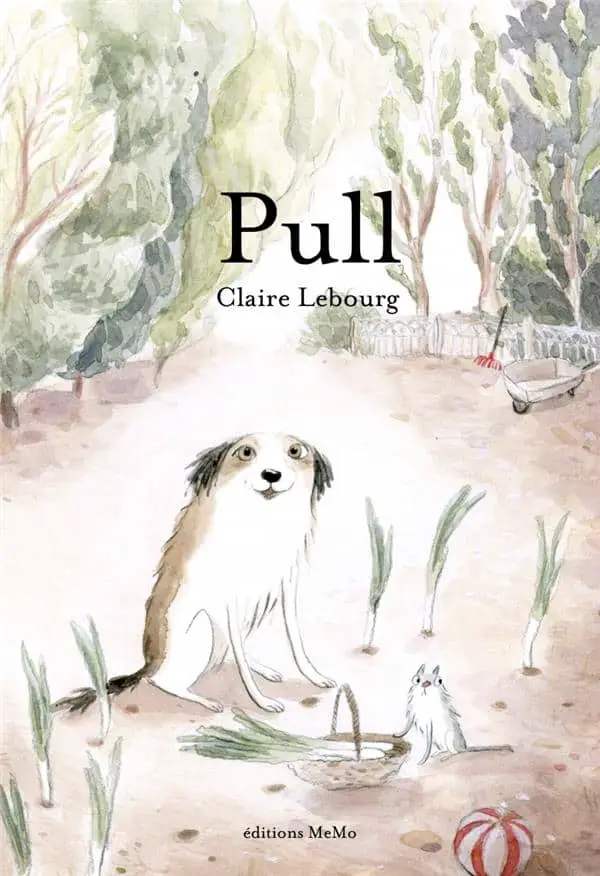

At the start of summer, Pull abandons his master at the Gare d’Austerlitz.

After following the aroma from a trash can, he must now face facts: Francis is lost. To reach him, Pull follows the train tracks to a small suburban station. He meets Groucho, a chihuahua who leads him to a decrepit train, serving as a makeshift shelter for abandoned dogs.

But Pull refuses to believe he has been abandoned like them: it is entirely his own fault that he and his master have been separated…

Though at first he refuses to take part in the group activities, he quickly introduces them to a new one. Main course: the leek-juice tart! Despite everything, Pull is determined to find his master.

Header illustration: 1955, “Go Two Miles, Turn Left…” artist- Amos Sewell (cover art for The Saturday Evening Post, July 9, 1955)