“Germans At Meat” (1910) is a short story by Katherine Mansfield, and opens her first collection (a series of journalistic travelogues). The collection is called In A German Pension.

Mansfield later regretted these stories and did not want to republish them in 1920, three years before she died. She considered them ‘immature’ and ‘a lie’. Unfortunately for Mansfield, a gaggle of us are still talking about them over 100 years later.

Some of the stories in this collection are said to be sketches rather than complete stories. But that depends what you mean by a story. Below, I consider from a wholly technical point of view whether “Germans At Meat” is technically a story or a sketch.

Also, what exactly made these early stories less mature than Mansfield’s later ones? Mainly it was to do with the narration and the imagery. She hadn’t quite cracked her sophisticated system of imagery yet, and she had not yet invented those trademark narrative techniques exemplified in her final “Prelude” trilogy.

THE NARRATOR (AND THE AUTHOR)

This is a first-person story. The narrator is a woman who has been married for three years. She’s clearly English, or of the British empire. Speculation: Katherine Mansfield had been married to George Bowden for about three months. Perhaps she told us the character had been married for three years so that readers would not conflate the character with the author herself. Women in particular are commonly assumed to be writing autobiographically. As Joanna Russ explained in her book How To Suppress Women’s Writing, “confessional” and “autobiographical” are pejorative when applied to women’s work.

I do feel, however, that this conversation is a hyperbolic patchwork comprising snippets of real interactions between Katherine Mansfield and Germans.

I also feel keenly, after reading a few biographies, that Katherine Mansfield lived with an eating disorder. It’s tempting to attribute her weight loss entirely to tuberculosis, since tuberculosis itself leads to weight loss (and back then, death). But it is entirely possible that Mansfield had TB and also disordered eating. Mrs Beauchamp, for one, was extremely critical of Mansfield’s weight. Looking at the photos of child Kathleen, she was a perfectly healthy-looking child and her weight was wholly unremarkable, especially by today’s standards. But as an example of her mother’s callousness, after being away on a world cruise for months and months, the first thing Kathleen’s mother said to her upon arriving back in Wellington was a dismissive comment about how she hadn’t lost any weight. Kathleen was the designated fat sister. As an adult, she was almost certainly a coffee and a cigarette for breakfast kinda gal.

Photos of adult Katherine Mansfield show us she was a smoker. I’m tempted to say ‘heavy smoker’ but then I think of my own grandmother, who was a light smoker but frequently shown posed in photographs with a cigarette. (The reason is two-fold: Photos tend to be taken when cigarettes are tend to be smoked; when asked to pose, smoking is something to do with your hands.)

Why did Katherine Mansfield take up smoking when it wasn’t culturally acceptable for women to do so? On the face of it, the answer is obvious. Katherine Mansfield didn’t give a crap about rules, and smoking was a small rebellion, along with cutting one’s hair into a bob. (Mansfield was a lot more ‘rebellious’ than that in her private life.) But there may have been another facet to Mansfield’s decision to smoke, a decision which unfortunately holds true for some young people who still take up smoking today: Smoking as a perceived weight loss tool. Also, we now know that weight loss itself can kick off a pattern of disordered eating.

Katherine Mansfield’s eating disorder is speculative, of course, though well within the realms of possibility.

Contributing to my views, Katherine’s own writing evinces a certain disgust of the human body and its functions:

- Herr Rat blows on his soup before eating it.

- The traveller from North Germany says he can’t keep sauerkraut down.

- The widow picks her teeth with her hairpin and talks about childbirth.

- The traveller speaks his potato with a knife.

- Herr Hoffman talks about sweating and wipes himself with the dinner napkin.

Disgust of the body frequently plays a part in disordered eating.

Considering the examples above, “Germans At Meat” is perhaps the standout example of Mansfield’s bodily horror. The Germans are very at home in their corporeal selves, but the narrator keeps changing the subject.

Or is Mansfield’s narrator simply expressing disgust at people who talk about such things over a shared meal? That could be true as well.

Another word we might use for the Germans is ‘vulgar’. The narrator focuses on table manners, emphasising the vulgarity of being human — a vulgarity which we try to cover up with fancy clothes and fancy china, but which is there, nonetheless. We ourselves are no more than walking meat-sacks, after all.

IMAGERY IN “GERMANS AT MEAT”

The narrator often uses imagistic language to express a repulsion for the characters. In the early stories [such as the German Pension collection] the narrator seems estranged from nature. the loud tones and sharp contrasts dominate. There is no atmospheric transparency in imagistic patterns, which is so evident in Mansfield’s later imagery. In In A German Pension imagery seems to originate not from any inner structural necessity, but to be introduced more or less at random.

Julia van Gunsteren, Katherine Mansfield and Literary Impressionism

So what imagery did Mansfield use in “Germans At Meat”?

The central symbol is the food, made clear from the first sentence:

Bread soup was placed upon the table.

Bread soup is heavy and filling, unlike clear broth. Whereas the Germans are very interested in food, the narrator is not. She hasn’t noticed what sort of meat her husband enjoys most. Sure enough, it’s difficult to find interesting imagery in this story. It’s not there. (I point you now to “Prelude” for lengthy notes about the extensive and masterful imagistic patterns.)

SETTING OF “GERMANS AT MEAT”

This entire story takes place at the dinner table in a pension (a boarding-house). The English narrator, along with the other characters, is on some sort of health jaunt.

Mansfield herself had a holiday in Germany, but we can’t really call it a holiday because she didn’t want to be in the spa town of Bad Wörishofen that June of 1909.

People went to this place for the restorative power of the baths (so-called) but biographers speculate Mansfield was sent there after a pregnancy.

In the wider world of the story, World War One is on the horizon. Within four short years, Germany and England will be on opposite sides of the conflict. Mansfield generally stayed away from broad politics. “In A German Pension” remains one of the few stories which goes anywhere near touching the political and military issues of her time.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “IN A GERMAN PENSION”

Is “Germans At Meat” a story or a sketch? If it contains the following components, however brief and suggested, then it counts as a complete story.

SHORTCOMING

Mansfield characterises the Germans by showing their behaviour at table. Note that the word is ‘meat’, not ‘meal’, suggesting a certain brutality: butchery, blood-lust. (By the way, ‘meat’ used to mean food in general, as you may already know from Shakespeare’s plays.)

The story focalises on the character named Herr Rat, who is not married, though the narrator is as important as he is. There are two ‘main characters’ in this one.

“I have had all I wanted from women without marriage.”

I’m not sure what this is meant to say about him. Egocentricity and selfishness? I doubt Mansfield was ever one of the ‘compulsory marriage’ crowd. Even the narrator in this story is married but not all that wedded to (heh) the idea of matrimony ‘to complete’ oneself, an idea which was gaining traction during Mansfield’s time.

DESIRE

The narrator wants to enjoy her meal in peace, preferably with English sensitivities towards etiquette, even though she is in German country. She’d also like to avoid political talk. Most of all, she’d like to be treated with respect, despite being a young woman in the company of older people, ready to dismiss her.

The need to be taken seriously is common to us all, and is the driving force behind much of what we do.

OPPONENT

The narrator is vegetarian. Insta-conflict. These Germans cannot imagine life without meat. During the meal, the narrator’s dietary choices contrast with the meat heavy (and quite ridiculous) diets of the Germans.

PLAN

The narrator tries her best to steer the conversation in a more genteel direction. The Germans find her too prissy. She doesn’t hold her own when her entire country is accused of eating too much, and they ridicule her secret regarding how to make a good cup of tea.

BIG STRUGGLE

The narrator is vegetarian, and doesn’t even eat breakfast. Yet with these Germans she feels the need to defend the tradition of an English breakfast. A poke at an English breakfast is a poke at England itself, dietary preferences aside.

From there the conversation descends into a political discussion. In 1910 a broader conflict is building between England and Germany. We now know this led to the first World War, starting officially in 1914.

The Germans have been poking fun at England all through the meal. Now they say, “If we wanted to take over England we’d have done it already.”

All the while, the narrator has been disgusted by the display of corporeal upkeep displayed at the improper venue of the dinner table — picking teeth and cleaning ears. There’s nothing like bodily fluids (or the suggestion of them) to elicit an abject response. The narrator, likewise, wants nothing to do with the Germans, either, and insists England would not want Germany.

ANAGNORISIS

After trying to change the subject multiple times, the narrator finally succumbs to the temptation to answer back. “I assure you we are not afraid,” she says when the unnamed traveller starts talking about the prospect of war between England and Germany.

Has something changed in the narrator? Also, why has Mansfield shifted from talk about food to talk of war? I can’t say I’m entirely clear on this. There’s not the usual symbolism to give us any help, either. This reinforces my idea that this story served as a catharsis for Mansfield, who seems to have grown exasperated by certain German people she came across in her travels.

From what I can gather, she has captured the essence of German turns of phrase. Germans are renowned for being serious.

Less subjective is the very common phrase you hear from Germans, “Be serious!” Mansfield has something very similar, if old-fashioned, here: “But you cannot be in earnest!”

I asked a German speaker. The German word “ernst” as an adjective corresponds somewhat to English “earnest” e.g. in the sense of “serious” but not “ardent”. So, a German might say “”Sie können doch nicht im Ernst sein!”” Germans might also say “Das ist doch nicht im Ernst gemeint!” or “Sie meinen das doch nicht im Ernst!”. (I’m told ‘doch’ is a word of emphasis and has no direct English equivalent.)

All this to say, Katherine Mansfield took a common German phrase and used it in a short story. This points to a somewhat keen observation of the Germans who surrounded her in Bavaria, and serves as observational comedy to anyone who’s noticed similar things.

NEW SITUATION

The story ends when the narrator retreats, closing the door behind her. This is a wholly unremarkable ending, right down there with, “Somewhere, a dog barked.”

RESONANCE

Like Mansfield herself, commentators tend to agree that this story isn’t one of her best, but these stories were necessary before the great ones emerged. There’s a clear progression from ‘decent’ writer to ‘great’. If it feels like a ‘sketch’ rather than a ‘story’, I believe it’s because the narrator (and by extension the reader) do not experience any revelation at the Anagnorisis part of the story. In contrast the Anagnorisis part of good lyrical short stories is the main aspect I’m able to flesh out when writing about them.

We’d feel less let down if we approached this story not as a lyrical one, with expectations of deeper meaning, but instead as a genre short story. What genre? Humour, probably, though I don’t personally find it all that funny.

Mansfield also wrote genre when she wrote “The Woman At The Store“, making use of supernatural tropes. In that story as in this one, she’s unable to shuck off her tendency to write lyrically, and lucky for us, she eventually went lyrical all the way. That’s what she was best at.

“A Dill Pickle” is another of Mansfield’s dialogue heavy short stories which takes place between characters at an eatery. If we see that as humorous, the humour is similar to this one. Dark. “A Dill Pickle” is (unfortunately) relevant to a contemporary audience. ♦

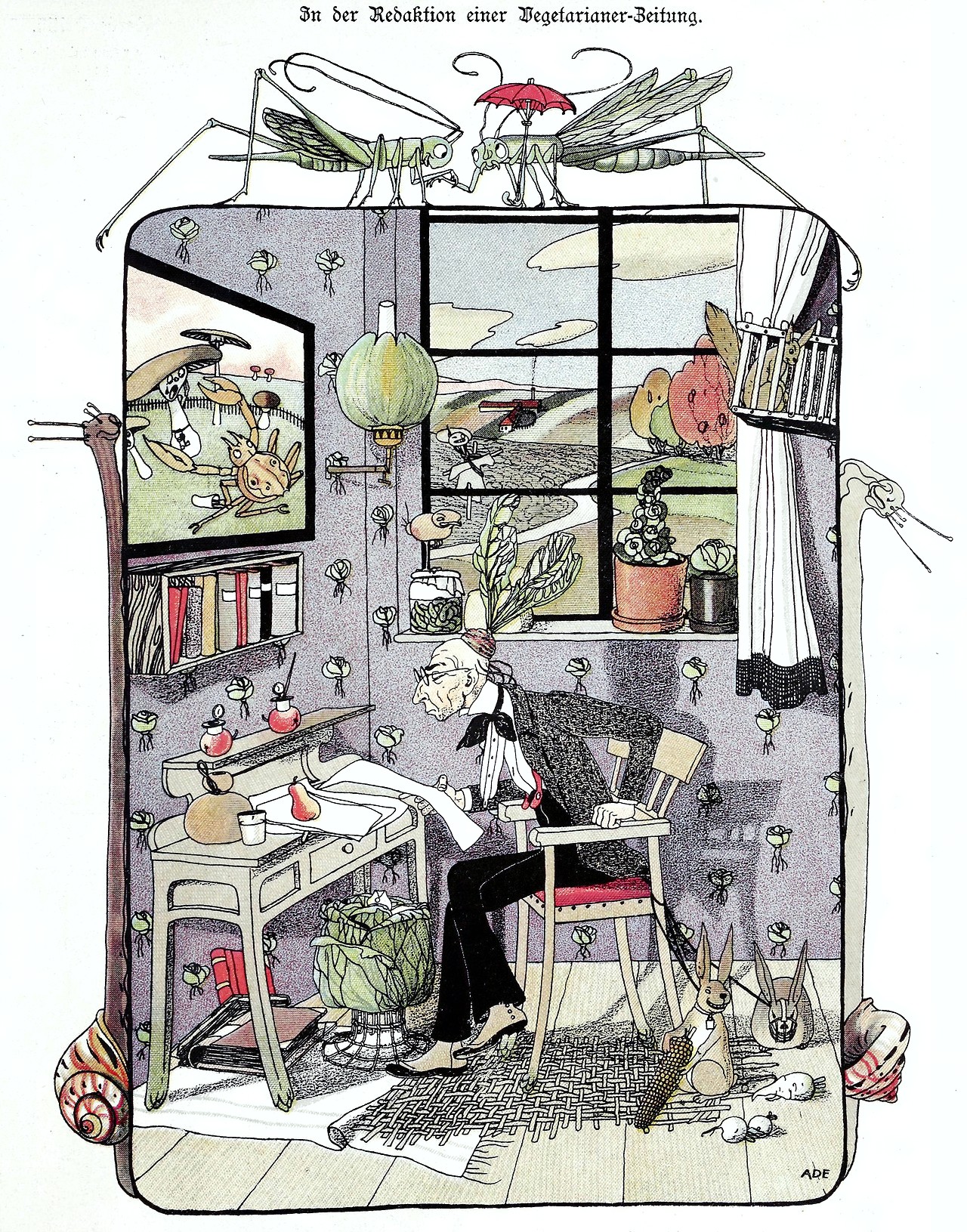

Header illustration: I found a Bavarian postcard from the early 20th century online, ran it through AI enlargement software, then used it as the basis for a digital painting.