In children’s literature and film, the big-name comedy series are male heavy. Even when women write comedy and humour, they have the best chance of striking it big if they write about boys.

Even better? The girls are arch nemeses (or sexualised enigmas) to the funny boys.

Silly as it may sound, critics are still scratching their heads over the question of “can women really be funny?”, which bleeds through into fiction as the question “should women be funny?” or “should we write women into funny roles?” As Dee noted in the AniFem premiere review, female characters as the sensible “straight man” to the hapless, entertaining male lead is a trope entrenched in comedy.

AniFem

The cultural values are male; for a woman to say a man is funny is the equivalent of a man saying that a woman is pretty.

Fran Lebowitz

CONTEMPORARY BEST-SELLING HUMOUR

At the top of best-seller lists in English speaking countries you’ll find the following humorous children’s books:

- Wimpy Kid series — male author — boy main character (American but popular worldwide)

- David Walliams books — male author — a range of adult/child main characters, with old and adult women funny but girl characters kindly and playing straight characters. (Especially big in the UK)

- Tom Gates books — female author/illustrator — boy main character, highly unsympathetic sister (UK)

- Beano books — an anonymous variety of contracted authors — boy main characters

- Treehouse books — male author and illustrator — author and illustrator friends are themselves juvenile characters in the books (Australia)

- Julia Donaldson picture books — female author/male illustrator — mixture of male and female characters (UK — the female characters who seem to break gender norms but who often actually don’t)

- Dog Man — male author/illustrator — male characters (USA)

- No one Likes A Fart — female writer/male illustrator — fart as main character, coded male (Australia)

- Wonky Donkey series — male writer/female illustrator — male main character

- Dork Diaries — MG — female author/daughter illustrator — female main character (USA — also has a spinoff series starring male character, Max Crumbly)

- Pig The Pug picture books — male author/illustrator — male characters (Australia)

- Hairy Maclary series — female author/illustrator — male gang of dogs and cats (New Zealand)

(As a side note, American bestseller lists feature more serious children’s books at the top, UK has more humour, and Australia/NZ has a higher tolerance for gross-out humour.)

Notice also that even when female characters are comedic, those characters tend to be older or elderly women. There are disproportionately few girls who star in their own comedies. There are even fewer in which boys play the ‘straight man’ to the girls.

A few exceptions exist in anime:

- Please Tell Me! Gaiko-chan — a cast of teenage girls engage in bodily-functions-based humour

- Lucky Star — an otaku comedy in which a female cast references and pokes fun at a geeky world traditionally considered the domain of boys

- Pop Team Epic — absurd, crass, slapstick humour carried out by two leading ladies, Popuko and Pipimi.

In general, though, female characters in anime are cute girls doing cute things, designed to be as appealing as possible. And so when a cute girl engages in shitpost humour, this employs the old ‘dog bites man’ inversion comedy. In other words, it’s even more funny because it’s a cute girl coming out with these crass things.

‘I mean, think of all those films or TV shows where there’s one woman, or one gay, in a script otherwise full of straight men, written by a straight man? Or a book? Fiction and film is full of these imaginary gay men and straight women, saying what straight men imagine we would say, and doing what straight men imagine we would do. Every gay I see has an ex-lover dying of AIDS. Fucking Philadelphia. I’ve started to think I should get an AIDS boyfriend, just to be normal.’

‘Yeah – and all the women are always just really “good” and sensible, and keep putting the men, with their crazy ideas, and their boyish idealism, into check,’ I say mournfully. ‘And they’re never funny. WHY CAN’T I EVER SEE A FUNNY LADY?’

from How To Be A Woman

GENDER DIFFERENCES AND WAYS OF CATEGORISING HUMOUR

What have academics learned about the gender humour divide?

The gender divide in humor: How people rate the competence, influence, and funniness of men and women by the jokes they tell and how they tell them by Christina Rozek

Gender and Humor: Interdisciplinary and International Perspectives edited by Delia Chiaro

Laughter, Humor and the (Un)making of Gender: Historical and Cultural Perspectives edited by A. Foka and J Liliequist

- Overall, the gender difference in humour is quite small and shouldn’t be overestimated. As usual, the differences between individuals of the same gender are bigger than differences across genders. However, there are noticeable trends, in general.

- Male and female humour often serves different purposes. Men: Use conversation to increase social status. Women: Use conversation to establish closeness. Humour follows the pattern.

- Men tell formulaic jokes more often.

- Women tell anecdotes and stories more often.

- As gender roles overlap, difference between male and female humour narrows.

- Negative and Positive Humour Categories:

- Self-enhancing: enhances self-esteem in a positive way. Includes the tendency to adopt the perspective of others, to have a humorous outlook on life, to use humor as a coping mechanism, and to engage in humor while not in the presence of others. [POSITIVE]

- Affiliative: Helps positively promote interpersonal relationships. Playfully joking with others, making witty statements, telling amusing stories, and laughing. [POSITIVE]

- Self-defeating: Enhances interpersonal relationships at the expense of the self. Places the joke tellers at the mercy of the audience, making him or her the butt of the joke. [NEGATIVE]

- Aggressive: Enhances the self at the expense of another. Sarcasm/teasing and as a method of criticizing or manipulating others. Humor with little regard for others. [NEGATIVE]

- Positive humour builds cohesion. Negative humour establishes and maintains social hierarchy.

- Positive humour more often used by women.

- Negative humour more often used by men, though self-deprecating humour is a form of negative humour used just as much by women.

- Another way of looking at ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ humour — Social reasons for humour:

- Introduce taboo topics

- Silence and subordinate individuals

- Create group solidarity

- Express hostility

- Educate

- Save face

- Ingratiate

- Express caring for others

- These functions can be more broadly categorised:

- To emphasise power differences

- Provide self protection, as self-defence or to cope with a problem

- Create or maintain solidarity within the group

- Other terms used to describe the same divide: inclusive/exclusive, affirmative/destabilising (in regards to the prevalent norms).

- These gender dynamics are established very early. Boys and girls grow up in different cultures.

- There’s no consensus about whether sexual humour is positive or negative — that’s in a category of its own.

- Both male and female humour has a long history of sexual and sexist topics but women have been taught not to use it outside all female groups. This leads to the misperception that women don’t find these jokes funny, or can’t crack sex jokes themselves.

- Men also use humour collaboratively, to maintain social relationships.

- Women’s jokes are more often constructed jointly by more than one person in a group.

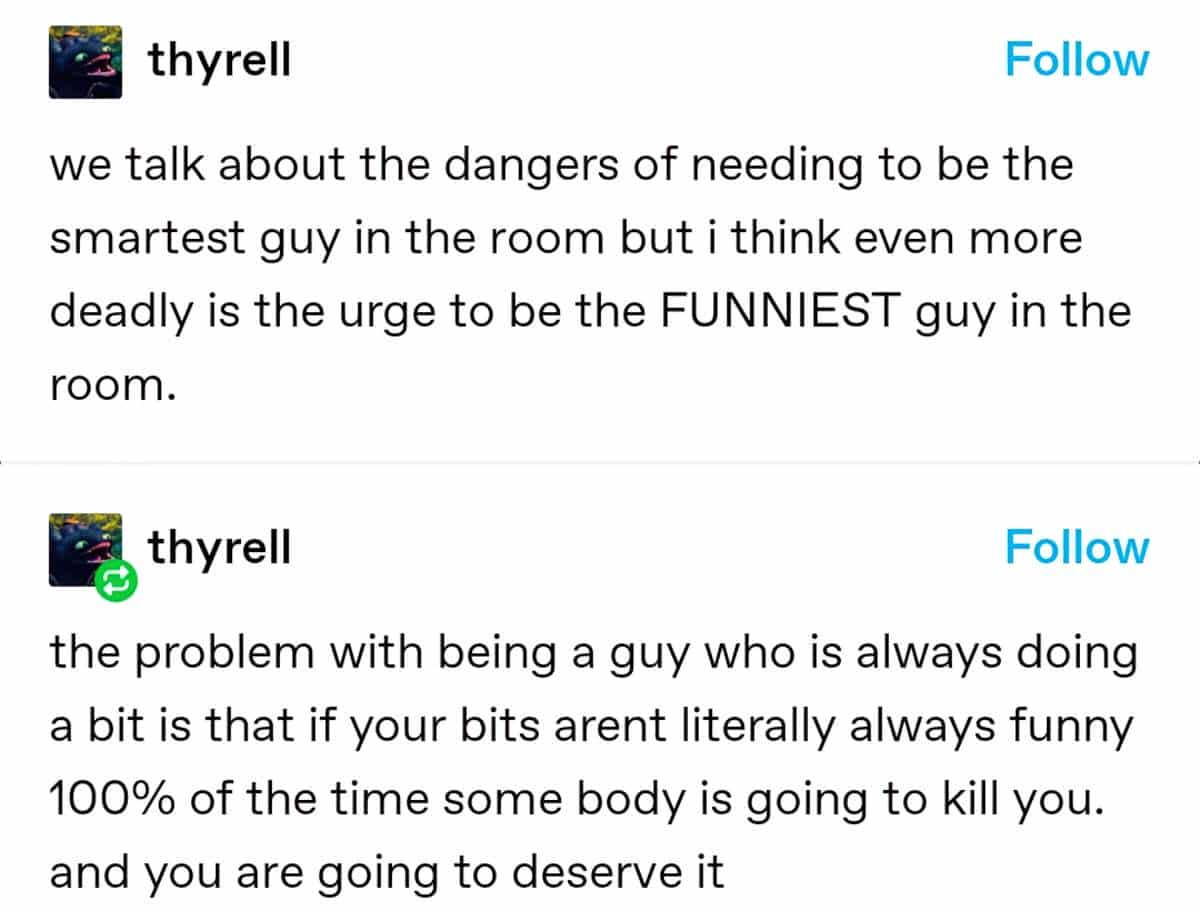

- Gender is highly performative. Having a laugh/fooling around is a compulsory part of being male. The most popular boy is probably perceived as the most funny.

- In the education system, playing the fool doesn’t go well with taking academic work seriously.

- In the workplace, women are rewarded for using positive styles of humour but more punished for using negative styles. (Men get away with being funny-mean — girls are expected to be nice.)

- It is widely believed that women are less able to tell jokes and also less able to appreciate jokes. When the same joke is attributed to a man/woman, participants will say it is funnier when told by a man.

- Women often make jokes that are funny to other women, and which men can’t seem to relate to.

- Historically, women’s role in creating humour has been overlooked.

- Men are more confident about their own ability to be funny. Men are also more likely to want ‘witty’ to be part of their identity.

- Women name both male and female comedians as favourites, but a lot of men have trouble naming even one female comedian.

- Men and women use humour differently when attracting ‘a mate’ (though this body of research is heteronormative). Women are attracted to men who make them laugh; men are attracted to women who laugh at their jokes.

(The research has mostly involved white, middle class university students. Until recently, there was no research into humour as it occurred in spontaneous conversation, which means professional — and mostly male — comedians have been disproportionately studied.)

A Brief History Of Gender and Humour

If a woman tells a joke and you do not laugh, she’ll look away, embarrassed.

If a man tells a joke and you do not laugh, he’ll repeat it, louder. If you still do not laugh, he will explain “that was a joke”.

Somehow this has led to men concluding that they’re the funny gender.

Jennifer Wright (@JenAshleyWright)

- In Roman literature the scheming, sexually voracious, and uncontrollable woman is often used as a negative paradigm to illuminate the corruption and decay of the Empire rather than to represent accurately historical womanhood in Rome. As a result, the idea of using women’s behaviour to represent the corruption of or deviation from societal norms has become a common device in both ancient and contemporary portrayals. These women ‘lack’ chastity, are ‘hegemonic’ (domineering) and display shrewd behaviour. In Ancient Greek humour, too, there’s a subgenre of comedy about adulterous wives. Women’s humour was often ribald and connected with women’s cults.

- In contemporary comedy we have Catherine Tate’s ‘Nan’, the older women of Absolutely Fabulous, Dawn French’s Vicar of Dibley, Fleabag and various other women who can also be described as ‘ribald’.

- In children’s literature, Roald Dahl and David Walliams repurposed this ancient variety of ribald woman in The Trunchbull, the witches, the awful auntie and so on. Being ribald is one way for a female character to be seen as funny, but girls cannot be ribald. This is reserved for older women who have lost innocence and sexual desirability from men.

- One of the most misogynistic works in Greek literature is a satire dividing women into types, composed by Semonides of Amorgos.

- Piglike, slovenly and rolling in mud

- Wily like the fox

- Nosy as a dog who her husband can’t constrain even by knocking out her teeth

- Compacted of earth

- Lazy and gluttonous

- From the sea

- Stubbon like an ass and just as lewd

- Weasel-like, sex-mad and thieving

- Born of a horse, daintily disdaining all work, sitting around making herself pretty

- Monkey offspring, the worst of all, ugly and vicious

- The only good kind of woman comes from the bee — modest, loving and gracious.

- He ends with the observation that ‘we men dote on our spouses and are all deceived’.

- Centuries later, Hippolytus wrote Euripides’s tragedy and parroted the same ideas in more absurd form. He wished men could deposit a sum of money in a temple to get a child instead of needing women.

- Academics often argue that these ancient men espousing hatred towards women are actually laughing at themselves for putting up with them and being beguiled by women despite women’s inherent terribleness. They argue that if these plays are read seriously, ignoring the irony, then they are being read ‘incorrectly’.

- Writers of contemporary children’s literature make use of watered-down versions of the same joke. In Australian illustrated MG novel Bad Guys, Aaron Blabey includes one femme character in the story — one of the male characters dressing as a woman to make himself sexually attractive to a male gatekeeper. At one point the male dressed as female bursts out crying. By doing so, he successfully dupes the male gatekeeper into paying him attention while his friends get what they want. The joke is ostensibly on the male gatekeeper for being so stupid as to fall for a male character obviously dressed as female. The effect on such jokes has a particularly serious impact for transgender women, whose murder rate hit a record high in 2017. I reject a non-ironic reading of such humour is the incorrect reading. The butt of the joke in this particular story is ‘this particular male character who fell for the ruse’ but, also, inevitably , ‘femme people in general’ are the butt . One side of the joke makes fun of an individual, fictional character. The other makes fun of an entire demographic of real people still fighting for equality. It is not possible to exploit the tropes of misogyny and make the main butt of the joke ‘men’.

FURTHER READING

Out of humour from Language: a feminist guide — an articulate primer on exactly why studies showing men are funnier than women are hugely flawed.

Schrodinger’s Douchebag: A guy who says offensive things and decides whether he was joking based on the reaction of people around him.

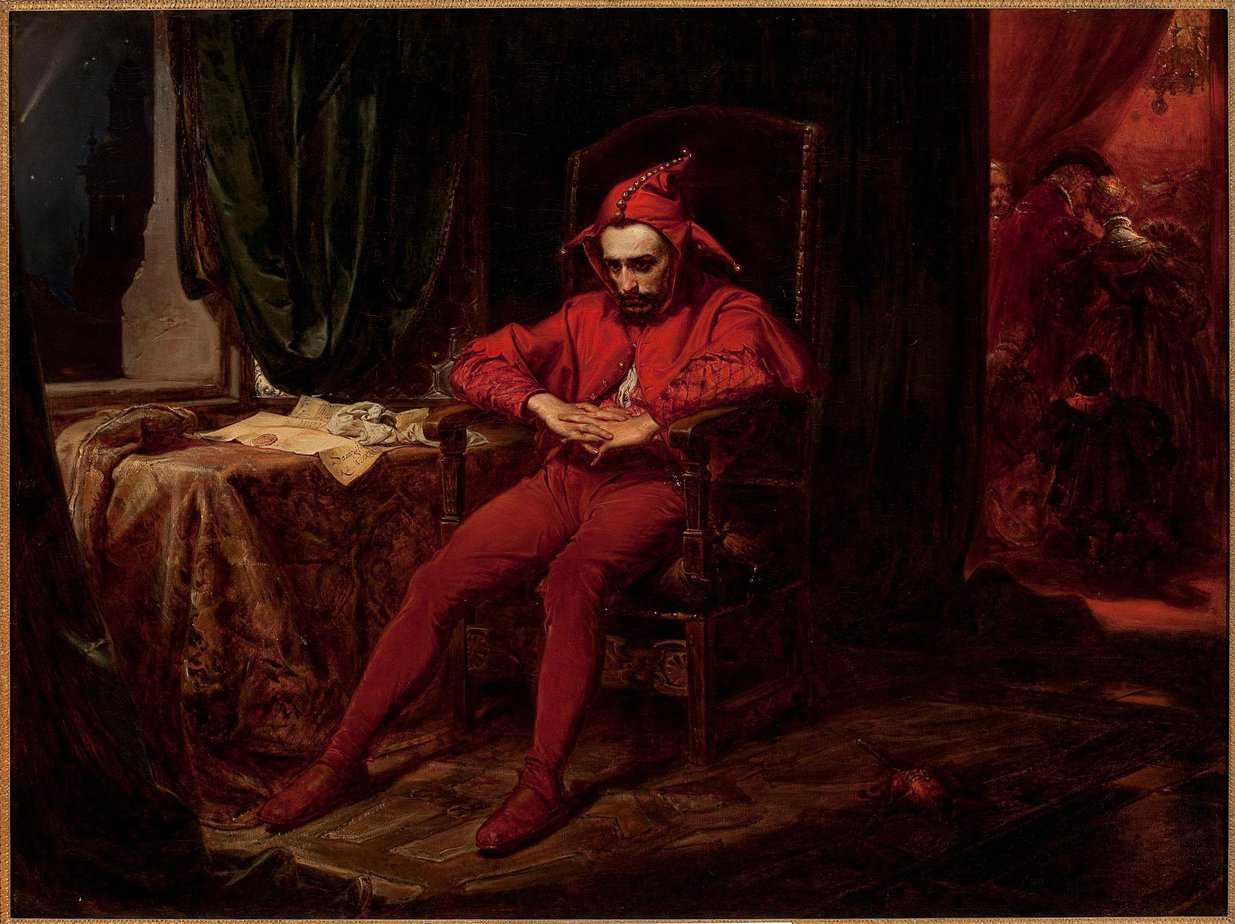

Laughing Histories: From the Renaissance Man to the Woman of Wit

Joy Wiltenburg’s book Laughing Histories: From the Renaissance Man to the Woman of Wit (Routledge, 2022) breaks new ground by exploring moments of laughter in early modern Europe, showing how laughter was inflected by gender and social power.

“I dearly love a laugh,” declared Jane Austen’s heroine Elizabeth Bennet, and her wit won the heart of the aristocratic Mr. Darcy. Yet the widely read Earl of Chesterfield asserted that only “the mob” would laugh out loud; the gentleman should merely smile. This literary contrast raises important historical questions: how did social rules constrain laughter? Did the highest elites really laugh less than others? How did laughter play out in relations between the sexes? Through fascinating case studies of individuals such as the Renaissance artist Benvenuto Cellini, the French aristocrat Madame de Sévigné, and the rising civil servant and diarist Samuel Pepys, Laughing Histories reveals the multiple meanings of laughter, from the court to the tavern and street, in a complex history that paved the way for modern laughter.

With its study of laughter in relation to power, aggression, gender, sex, class, and social bonding, Laughing Histories is perfect for readers interested in the history of emotions, cultural history, gender history, and literature.

New Books Network