Gaston is a picture book written by Kelly DiPucchio and illustrated in beautiful naive style by Christian Robinson. The colour palette is gorgeous.

I liken Gaston to another popular contemporary picture book: Drew Daywalt’s The Day The Crayons Quit. The plots are not at all similar, but they share the same ideological problems, intending to say one thing, inadvertently saying another.

SETTING OF GASTON

France, mostly inside a house, also at a park.

STORY STRUCTURE OF GASTON

Gaston is a spin on The Ugly Duckling and all those descendent stories for children about a young character accidentally switched at birth into the wrong family. In The Ugly Duckling, the beautiful swan finds its ‘rightful’ place among the other swans. Gaston inverts that outcome; after discovering the switch, Gaston stays with the family he has already bonded with. (Inversion does not equal subversion.)

PARATEXT

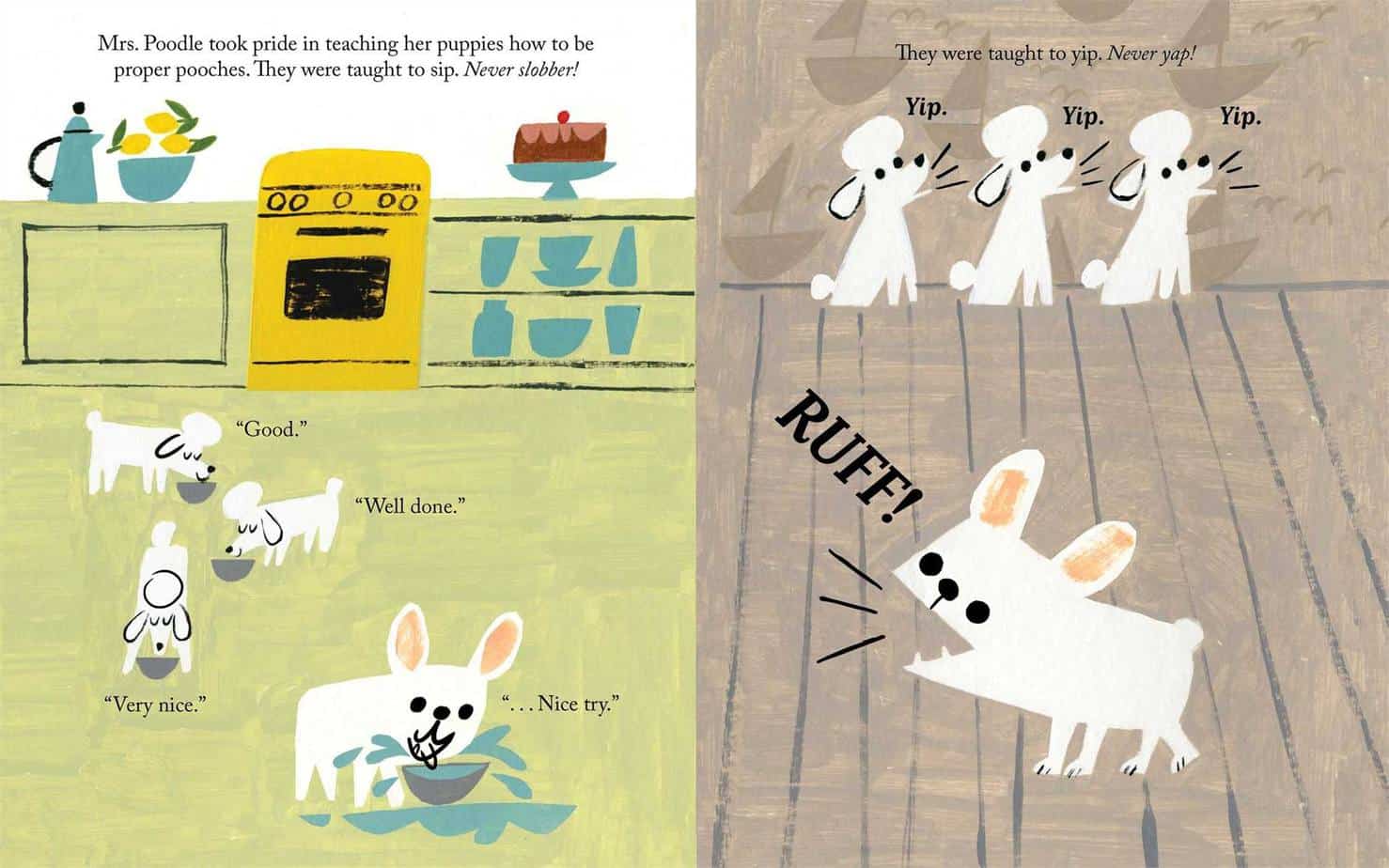

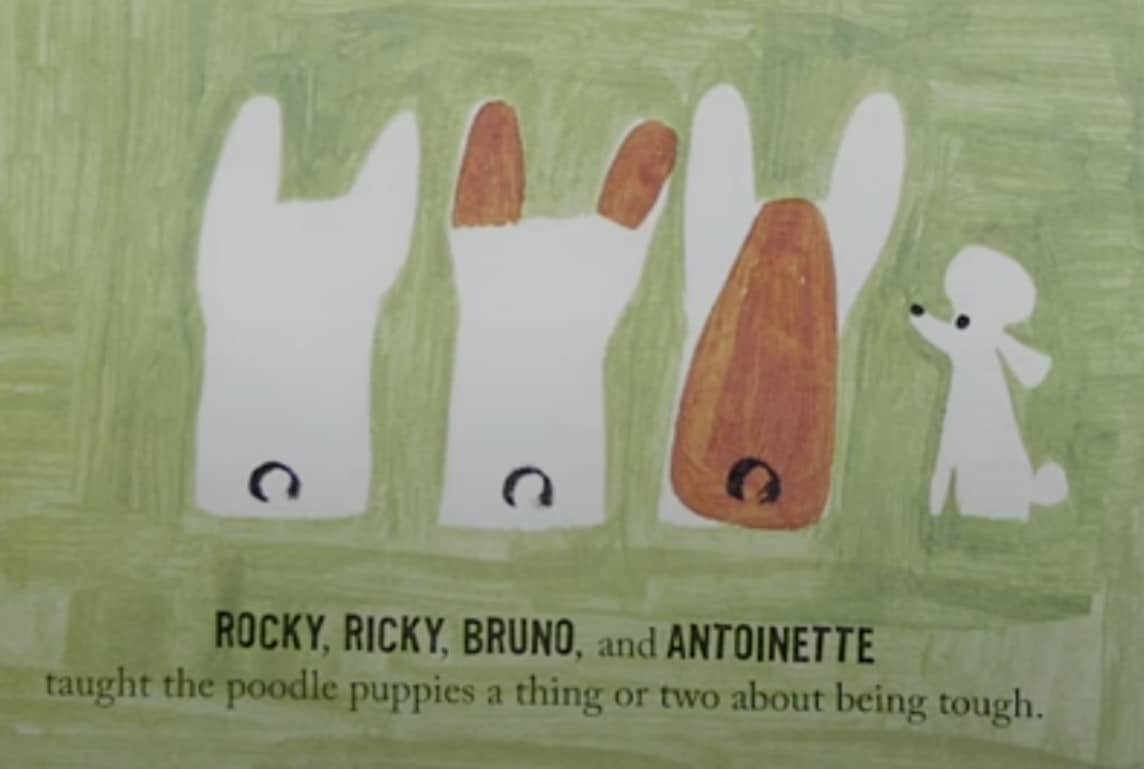

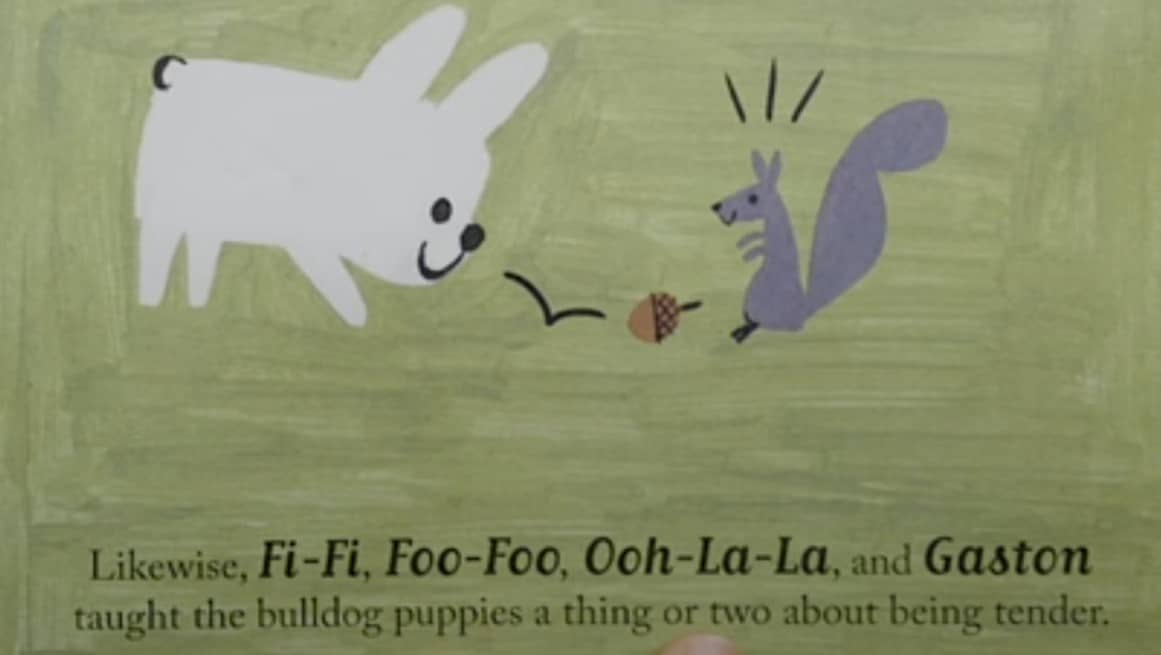

This is the story of four puppies: Fi-Fi, Foo-Foo, Ooh-La-La, and Gaston. Gaston works the hardest at his lessons on how to be a proper pooch. He sips – never slobbers! He yips – never yaps! And he walks with grace – never races! Gaston fits right in with his poodle sisters. But a chance encounter with a bulldog family in the park-Rocky, Ricky, Bruno, and Antoinette-reveals there’s been a mix-up, and so Gaston and Antoinette switch places. The new families look right…but they don’t feel right. Can these puppies follow their noses-and their hearts-to find where they belong?

MARKETING COPY

SHORTCOMING

The first thing that stands out about this book: it appeals to readers who subscribe to gender binary ideas. For readers with a more sophisticated understanding of sex and gender, this story is frustrating as all get out.

We commonly gender dogs, even though dogs are agender. (Dogs have sex, not gender, which is a — human — cultural construct.) Because we are human, and gendered, we tend to consider pretty dogs such as poodles girls, and broad, big-boned dogs such as the bulldog boys. (Gaston is a white Frenchie.) I even know someone who, as a kid, used to think dogs and cats were males and females of the same species. My dog happens to be a long-haired Border collie and strangers always gender him female. I’m sure it’s because of the long hair, and his prettiness. It doesn’t matter. That’s my point.

Are the poodles female? We don’t know, because of this cognitive bias to apply gender to animal species and breeds. Instead, for the purposes of my argument, I’ll call the poodles ‘femme’. Young readers will decode the poodles as good, well-behaved little girls, as they are meant to.

At the story’s opening, note that the femme characters are given cutesey non-human names while the masculo-coded dog, Gaston, is the only character with a human name. Beatrix Potter did the same thing with the naming of Peter (Rabbit) and his three sisters Flopsy, Mopsy and Cottontail.

You know who else divided names along human/gender lines? Jennifer and Matthew Holm in the Squish series, another book with massive gender problems. But this time they did the opposite. The girl is the only one with a human name.

The boys get cool amoeba names (Squish and Pod) whereas the girl blob is called a real world feminine name (Peggy). This seems like such a small thing, but is a sure sign that the main point of interest of Squish and Pod is that they are amoebas, whereas the main thing to remember about Peggy is that she is a girl. Peggy is annoying to the boys because she is super positive all the time. She even loves detention and tests. She constantly calls things ‘cute’. We are reminded time and again that she is very stupid. She is told by the boys at one stage that she talks too much, and the onomatopoeic label associated with her is literally ‘yammer yammer yammer’.

All this to say, when a storyteller decides to give all the boys human names and the girls cutesy names — or vice versa — look out for deeper issues. Spoiler alert: It’s never a good sign. (If names are divided along gender lines, the characters themselves will be strictly divided along gender lines.)

Back to this picture book, if the reader hasn’t picked up from the cover that Gaston is the empathetic viewpoint character, the human naming more subtly hammers home our empathy for Gaston.

DESIRE

Gaston and his femme doggy housemates are doing just fine, living in a house, compliantly doing as they’re told. But one day at the park their mothers meet and realise one member from each of their litters has been swapped. The mothers are very modern in their parenting. This is something we don’t see much of in children’s books from earlier eras — they let the children make big life decisions that affect them the most.

This kicks off the desire line: Gaston and Antoinette (who along with all of her male house mates also has a human name) want to find out where they belong. Belonging is the deeper desire and need of this story.

Significantly, there was nothing wrong with their lives until the mix-up was discovered.

OPPONENT

The opponent here is ‘The Situation’. Whoever accidentally swapped the pups is an ‘off-the-page’ opponent. The non-related siblings also form opposition, if only because they are different and therefore contribute to the switched puppies’ sense of isolation.

PLAN

The mothers make the plan. (The fathers are entirely absent.) They will let the swapped pups decide which family to join.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

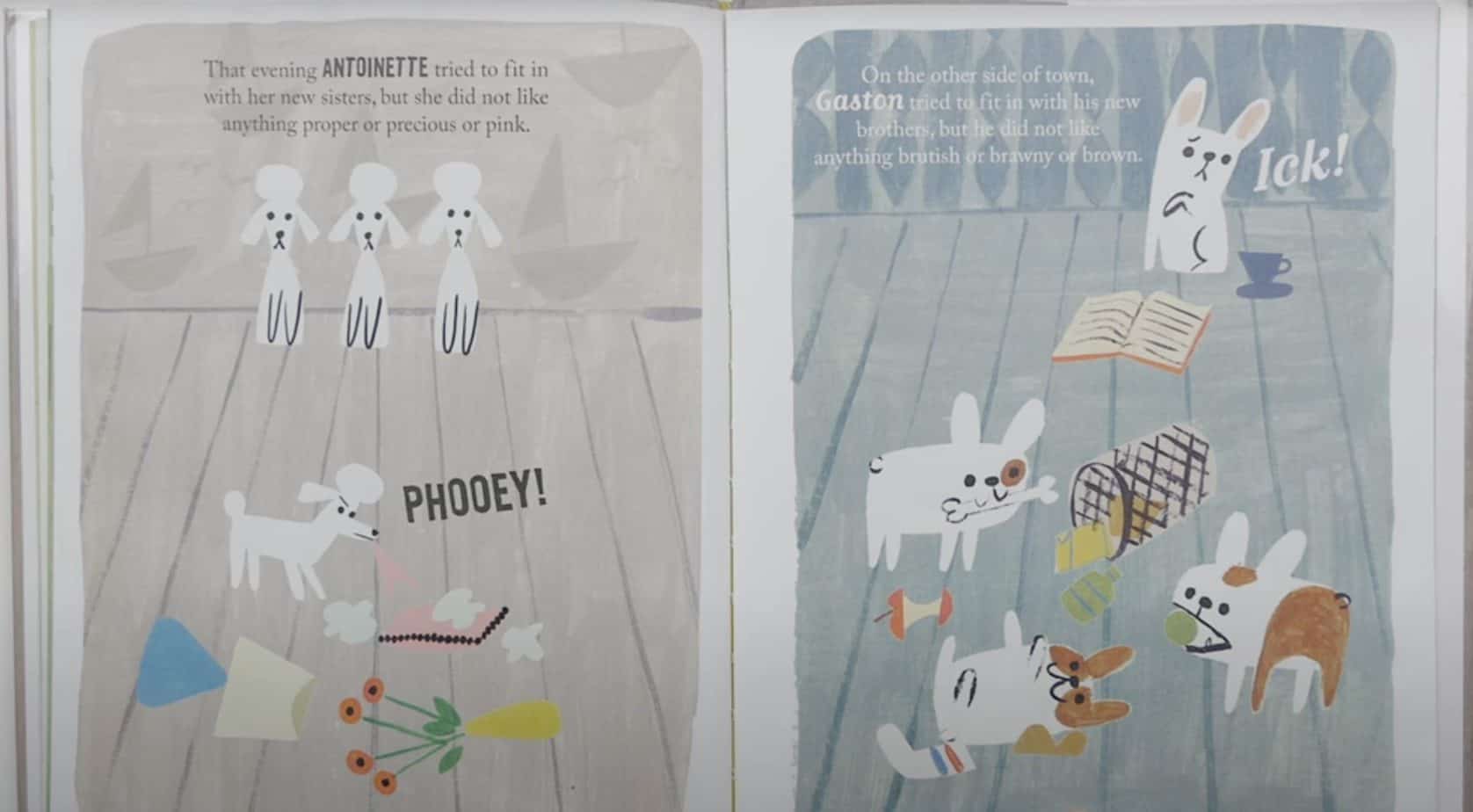

The pups swap houses, in a plot also utilised by shows such as Wife Swap, in which things never go well, do they?

ANAGNORISIS

This is the part of the book which tries to lampshade some highly problematic ideology. For many readers, it clearly does the job.

Below is a picture book version of feminism I’ve seen a lot, and at first glance it may seem enlightened. But this idea rests upon essentialist ideas about gender: namely, that boys are tough and girls are tender. Both are good! (Blergh.)

The message is clearly that both [sic] genders can learn the strongest points of gender from each other.

NEW SITUATION

Then there’s a decent solution: The puppies will return to their ‘adoptive’ families but will continue to see each other at the park. This is reminiscent of modern, open adoptions (compared to the more common and problematic closed adoptions of yesteryear).

And many years later, when Gaston and Antoinette fell in love and had puppies of their own, they taught them to be whatever they wanted to be.

Gaston

Heteronormativity endures in picture books, so I’ll leave that alone.

What really gets on my wick is the psuedo-enlightened message that closes out this book. That final sentence expresses a genuinely enlightened idea, but it comes on the back of an entire story underscoring icky gender essentialism.

This makes me wonder how earlier drafts of this picture book looked. This final sentence feels like a Band-aid slapped onto a gaping wound of old-fashioned ideas.

The Day The Crayons Quit falls into the exact same trap.

On the surface, The Day The Crayons Quit contains a message for young artists: Use all the colours in your crayon box. Use them in original ways. (‘Think Outside The Crayon Box’.) And the gender message for boy readers: If you’re a boy, don’t be afraid to use the pink crayon. There is also another message, more implicit than that: Pink is for girls, and girls are one big blob of similar people who ‘colour within the lines’.

Likewise…

On the surface, Gaston contains a message for young artists: You can be whoever you want to be. The gender message for boy-identified readers: You’re allowed to be tender. The gender message for girl-identified readers: You’re allowed to be tough. There is also another message, more implicit than that: Girls are naturally tender, boys are naturally tough.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: It’s the implicit messages that are by far the most effective in children’s stories.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Gaston is definitely one of those stories that will be read depending on what the reader brings to it (similar to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz).

Some readers find the story uplifting:

I really liked this one. A tale of two puppies that may somehow have gotten switched. A celebration of differences. An affirmation of being yourself.

CONSUMER REVIEW

There are messages here, but they’re only offered, not preached, and so the reader has a chance to choose which to explore and which to skip. Maybe it’s about adoption. Maybe it’s about just plain being happy with who you are. Maybe, even, it’s about transexuals [sic].

CONSUMER REVIEW

This is about a bulldog that gets mixed up with a poodle family and vice versa. It’s about embracing differences but it also represents adoption and how a person might look different from others in the family but is a member all the same. You could also use it to discuss how some people have to work harder at being good at something than others. A surprising amount of themes are layered in this picture book.

CONSUMER REVIEW

Other readers, myself included, find the messages troubling.

If you’ve seen the feature-length documentary Three Identical Strangers, your reading of this picture book will certainly be affected. It’s no small thing to realise your family is not what you thought it was. In fact, the consequences are devastating.

However, fiction commonly makes light of situations that in real life lead to trauma. Light treatment of a heavy situation is not necessarily a problem in and of itself.

But if you’ve also read Tree of Strangers by Barbara Sumner, or listened to her speak about adoption laws in interview, the ideology behind Gaston becomes even more problematic. Sumner, herself adopted, believes that taking a baby away from its expected mother causes trauma which we have long ignored because the trauma is happening to people still far too young to express that trauma.

The illustrations are great but an underlying message of the story is problematic. On one level, it’s a sweet story about belonging and family but on another level it seems to reinforce gender stereotypes with tenderness depicted as innately feminine and brutishness masculine. Maybe I’m reading too much into it but that’s how it strikes me.

CONSUMER REVIEW

I doubt the storytellers behind Gaston intended to write a story that gets into nature and nurture (it’s never one or the other, always 100% both). But a plot like this one cannot avoid it in readers who consider stories a part of the wider culture rather than as islands of fantasy that exist alone.

I was troubled by the resonances of the story. I don’t really think we’re all nature or all nurture. I don’t want kids to think that. This book basically does say NATURE WINS HANDS-DOWN BOOM. I also wonder what adopted kids would think of this book — that they’ll never truly belong with their adoptive family because there is a REAL family out there that’s exactly like them that they should really be with? Yeah, I’m probably overthinking this. But I would totally give this to adult lovers of cool art and French bulldogs and poodles. Not to kids.

CONSUMER REVIEW

RESONANCE

The optimist in me believes this book will look glaringly, hopelessly outdated in another 10-20 years’ time, and not just to the few of us who already understand gender as a spectrum rather than as a binary, with differences between individuals more significant than differences between genders.