The Garden of Abdul Gasazi (1979) was the first picture book by American author/illustrator Chris Van Allsburg, who himself admits astonishment at the book’s immediate success. This was helped by reviews in America-wide publications. Such attention has always been unusual for children’s stories, and perhaps says something about how this story appeals to all ages. Like Australia’s Shaun Tan, the picture books of Chris Van Allsburg work as coffee table displays, and you could easily hang these illustrations on a wall as fine art.

Van Allsburg credits his inspiration for this story to the random sight of a boy chasing a dog through a garden. He started to build a story around that real life scene until he came up with fully-fleshed plot of The Garden of Abdul Gasazi.

Authors will often tell us it’s a small incident like this which sparks a story. What we (and they?) are perhaps less cognizant of: The massive corpus of story which came before us all, and which informs our collective sense of story at the deepest psychological level. Perhaps Chris Van Allsburg has never read a fairy cup story in all his born days, but that doesn’t matter; this is nonetheless a descendent of the fairy cup legend. Perhaps he came across it in The Adventures of Alice In Wonderland, in which a child also chases an animal through a portal and ends up in a magical, slightly creepy land. In this story I also see shades of Jack and the Beanstalk, with a boy bravely confronting a ‘giant’ in his own lair in the hopes of carrying out duties expected of him by a mother (or mother figure). I also think of Puss In Boots when I see the tiny boy at the magnificent house, brave despite the huge difference in social standing. Then there are all the stories about transmogrification. We find those in every culture.

The Garden of Abdul Gasazi is an Odyssean mythic journey in which a young man journeys along a road, bravely confronts his greatest opponent and returns home (or to a new one) a changed man.

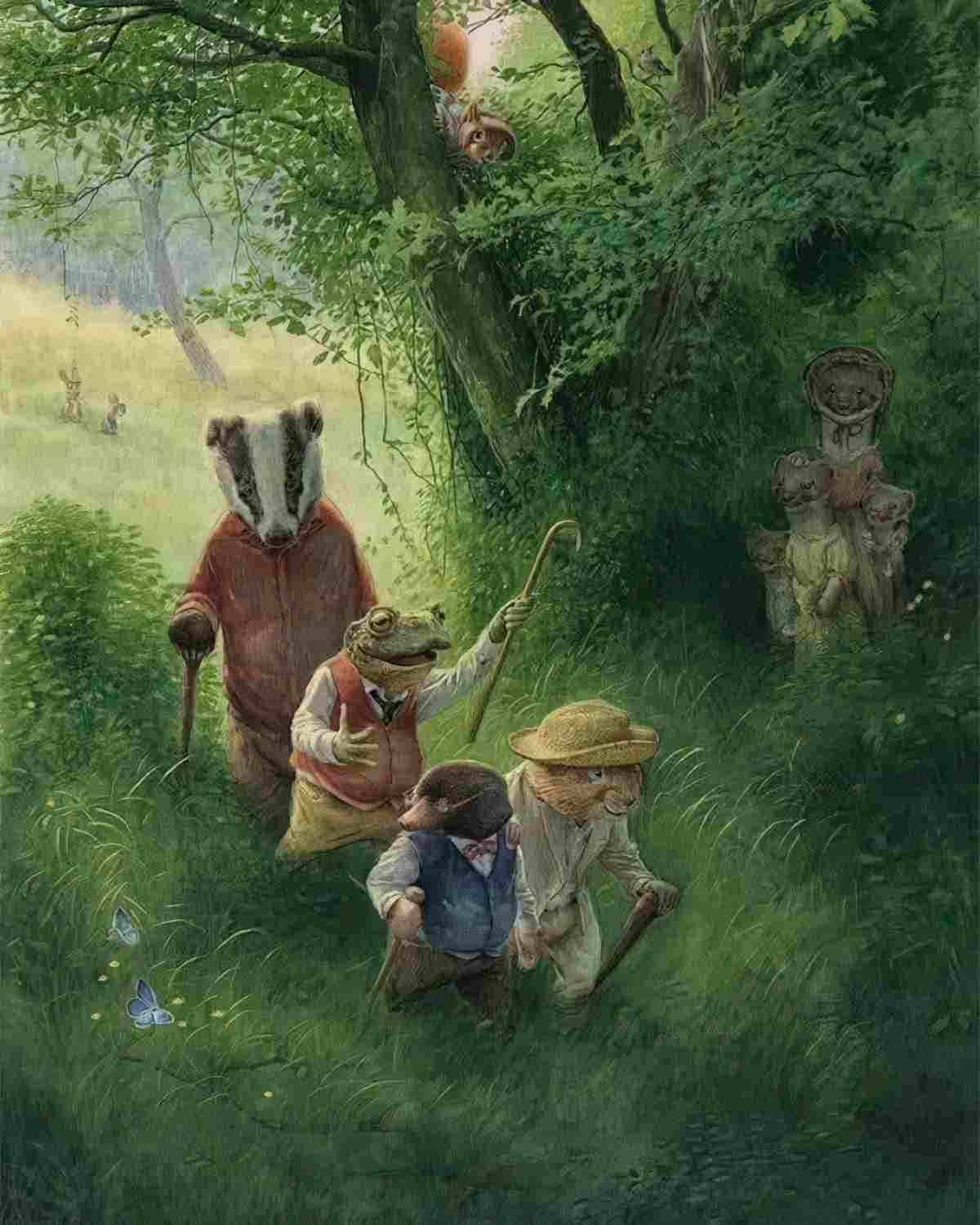

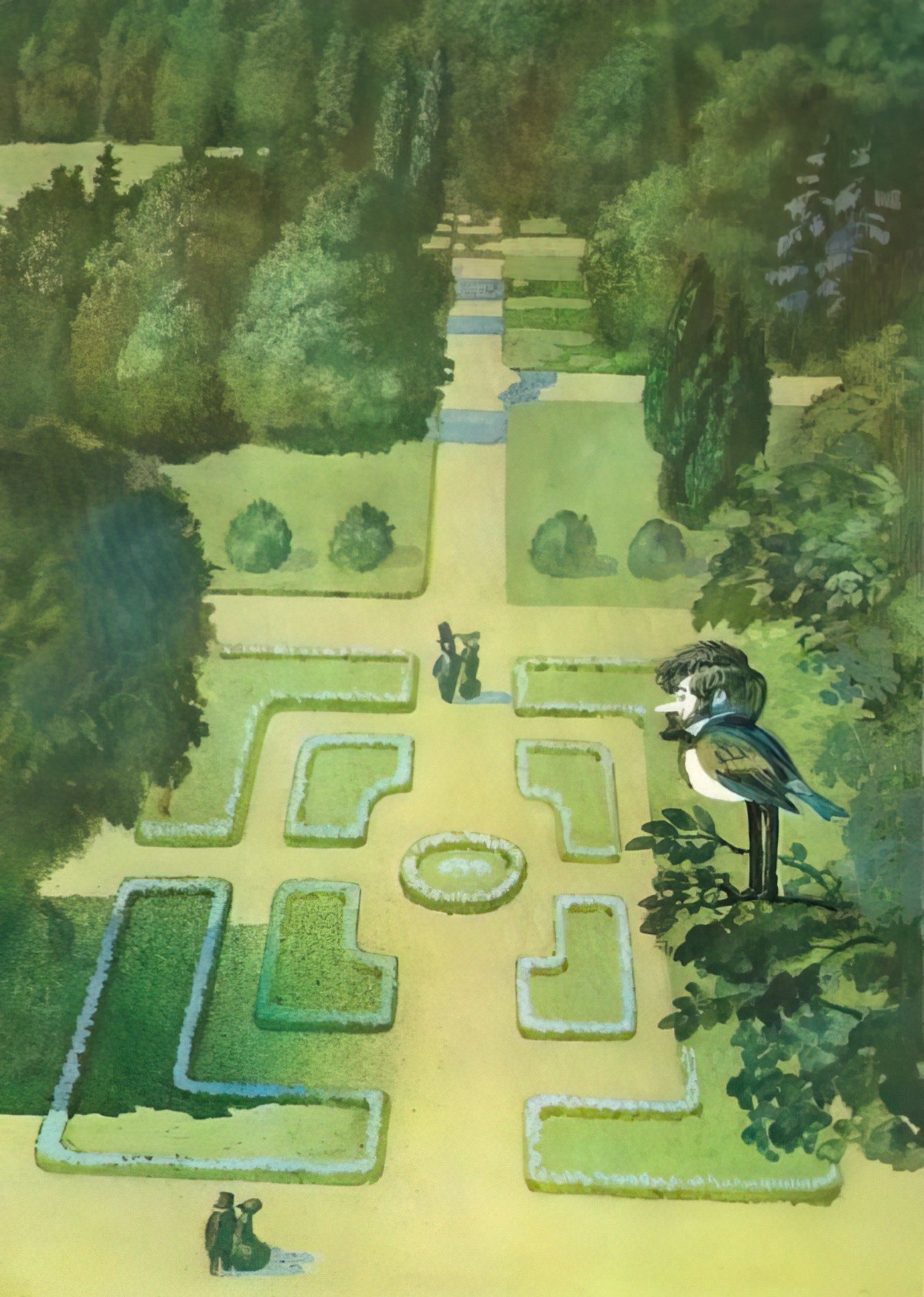

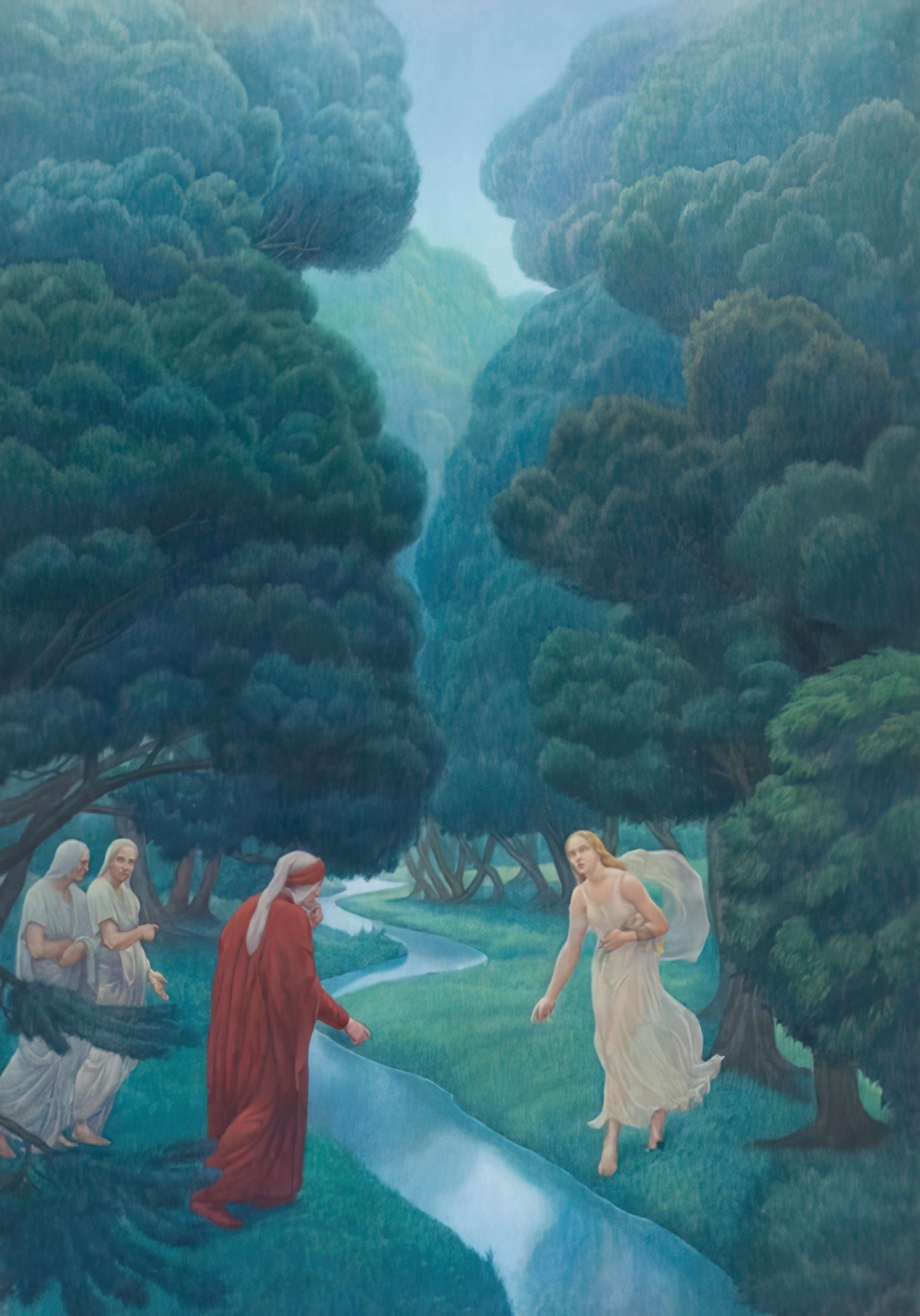

Below is another similar composition featuring characters on a mythic journey of their own: The animals from Wind In The Willows by Kenneth Grahame, illustrated by another artist by the name of Chris: Chris Dunn.

SCULPTORS AS STORYTELLERS

The drawing of Miss Hester on the opening page was the first Van Allsburg created for this book and, amazingly, “probably the eighth or ninth drawing I had done in my entire life,” Van Allsburg said in interview. But he wasn’t new to art. When he came to 2D illustration, he brought with him a background in sculpting. (He shares his sculpting expertise with another master of the short form, Irish/English writer William Trevor.) I believe Van Allsburg’s sculptor’s eye shines through in his illustrations. Despite being static images, those clear, straight lines of the buildings have an almost ASMR effect on me, and I’m sure on many others.

Notably, also, Van Allsburg has an instinctive interest in how objects cast shadows. This likely also comes from his background as a sculptor. Shadows don’t normally loom large in picture books for children, at least they didn’t until Chris Van Allsburg burst onto the scene with this story. As you re-read The Garden of Abdul Gasazi, be sure to pay attention to what he does with the shadows, because the shadows carry meaning.

THE ‘UNDERWATER’ GARDEN OF ABDUL GASAZI

If we divide picture book illustrators into two basic groups: Theatrical and Cinematic, Van Allsburg illustrates with cinematic perspective. We feel as though we are watching events play out via a camera rather than from a (comfortable and safe) seat in a theatre. This ‘camera’ seems to float through the air like a predatory fish through water, contributing to the ominous atmosphere of the garden. (Horror film-makers are familiar with this technique and utilise it often.) The garden has a slightly underwater feel as a result.

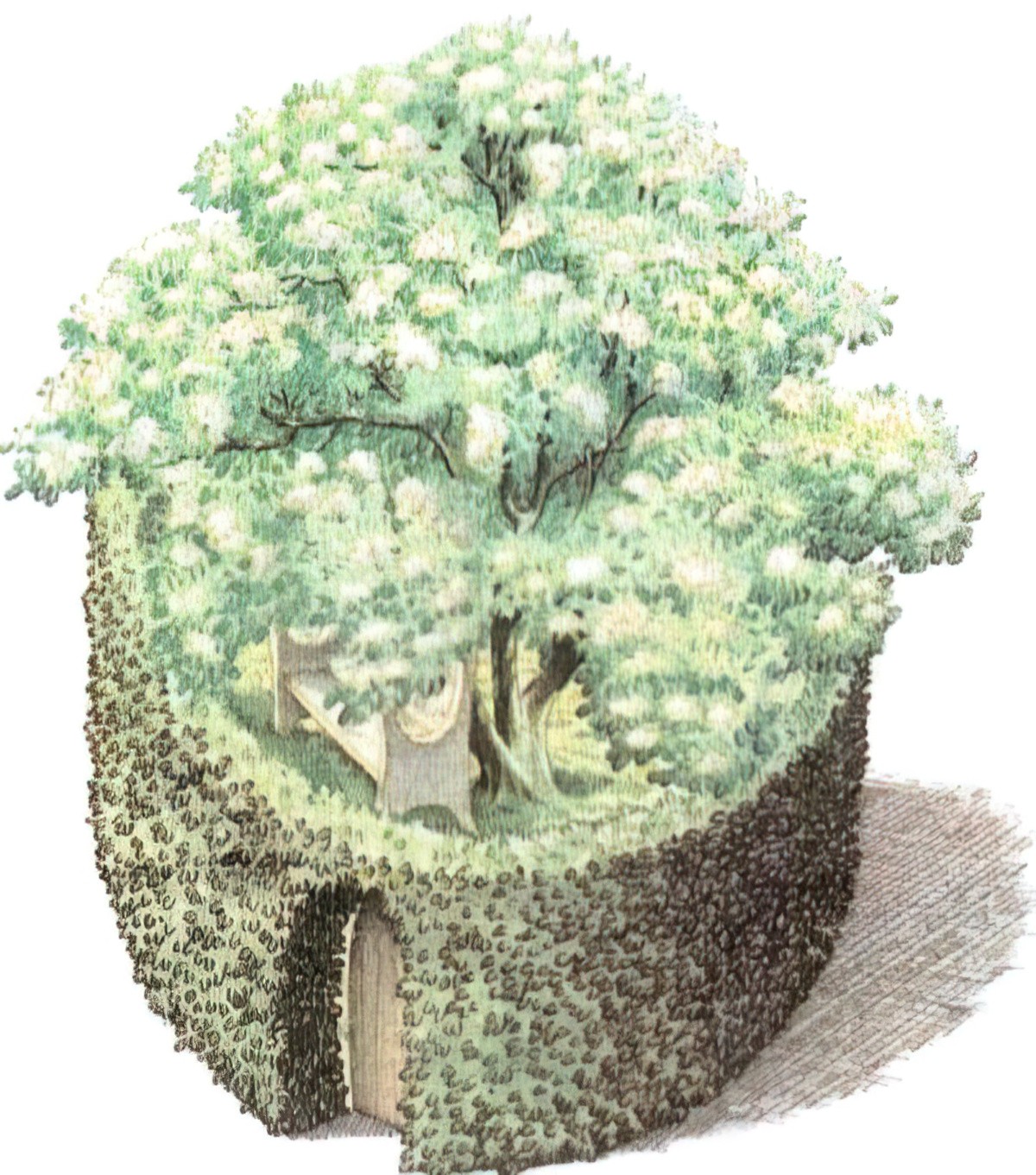

Third, the bushes of this garden have been created by an intradiegetic sculptor… and by a real life artist who notices and appreciates the shape of things.

UNSETTLING TRANQUILITY

The garden depicted in Abdul Gasazi is not your English country garden. It is something far more sinister, partly bcause it maintains the clean, symmetrical lines of the formal English gardens of aristocracy.

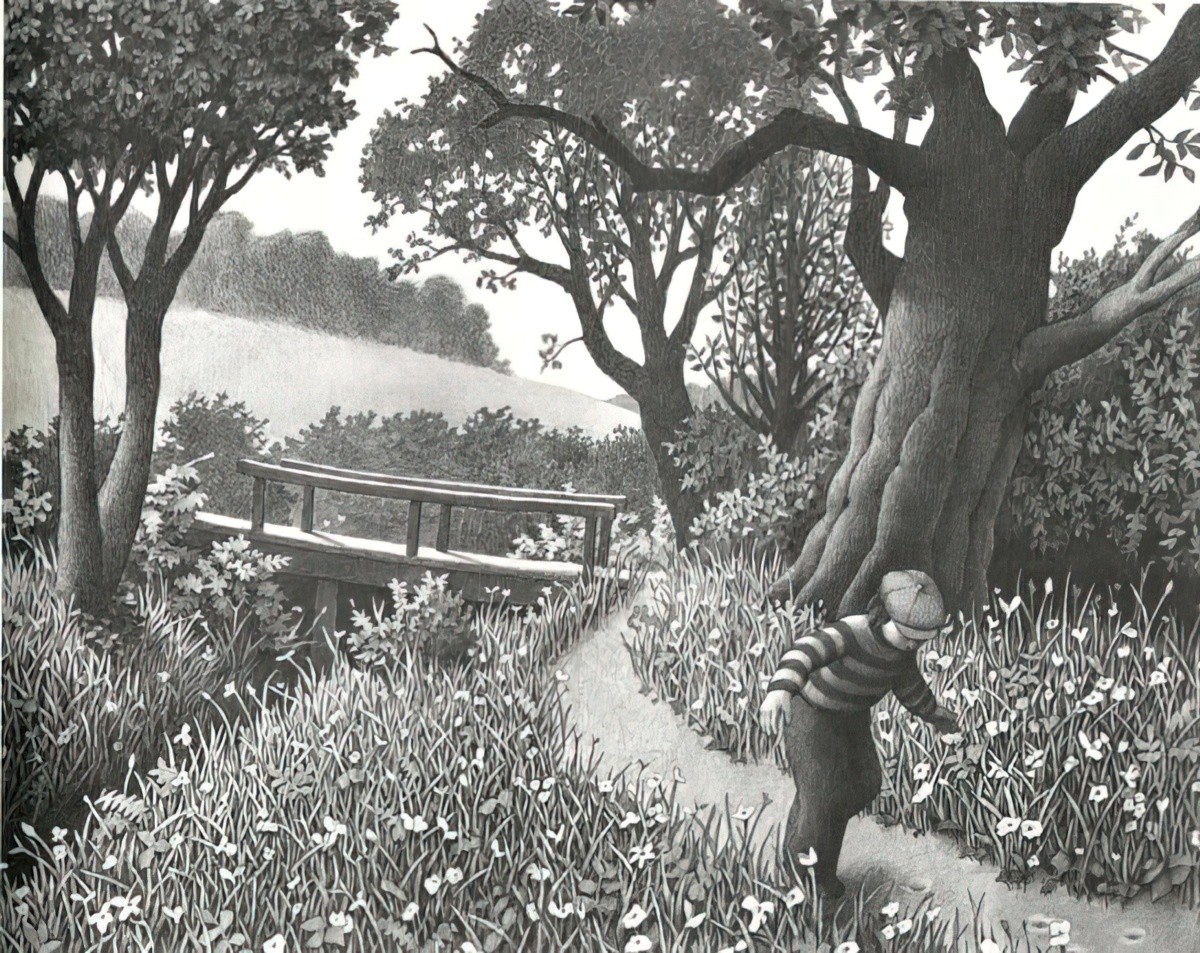

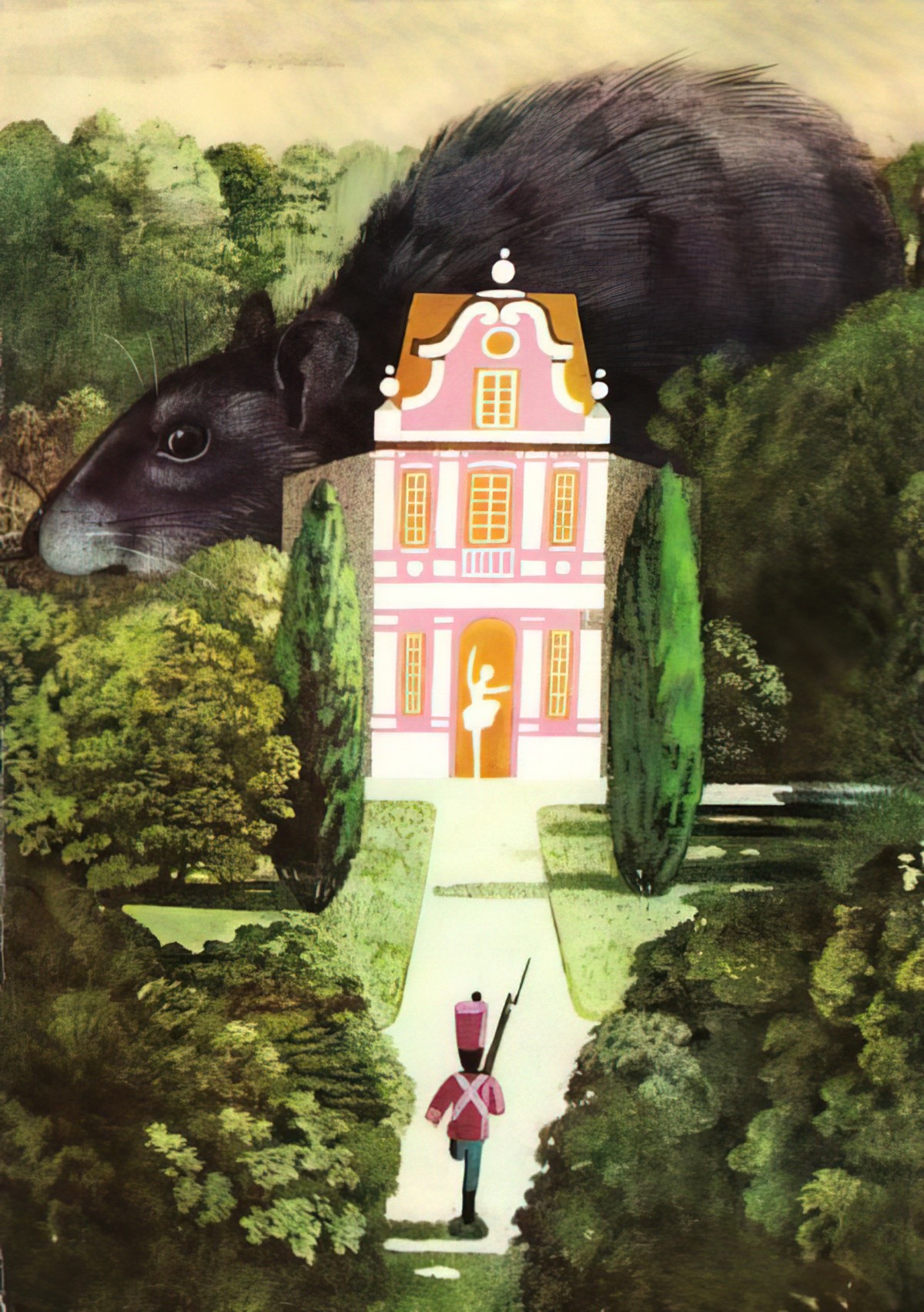

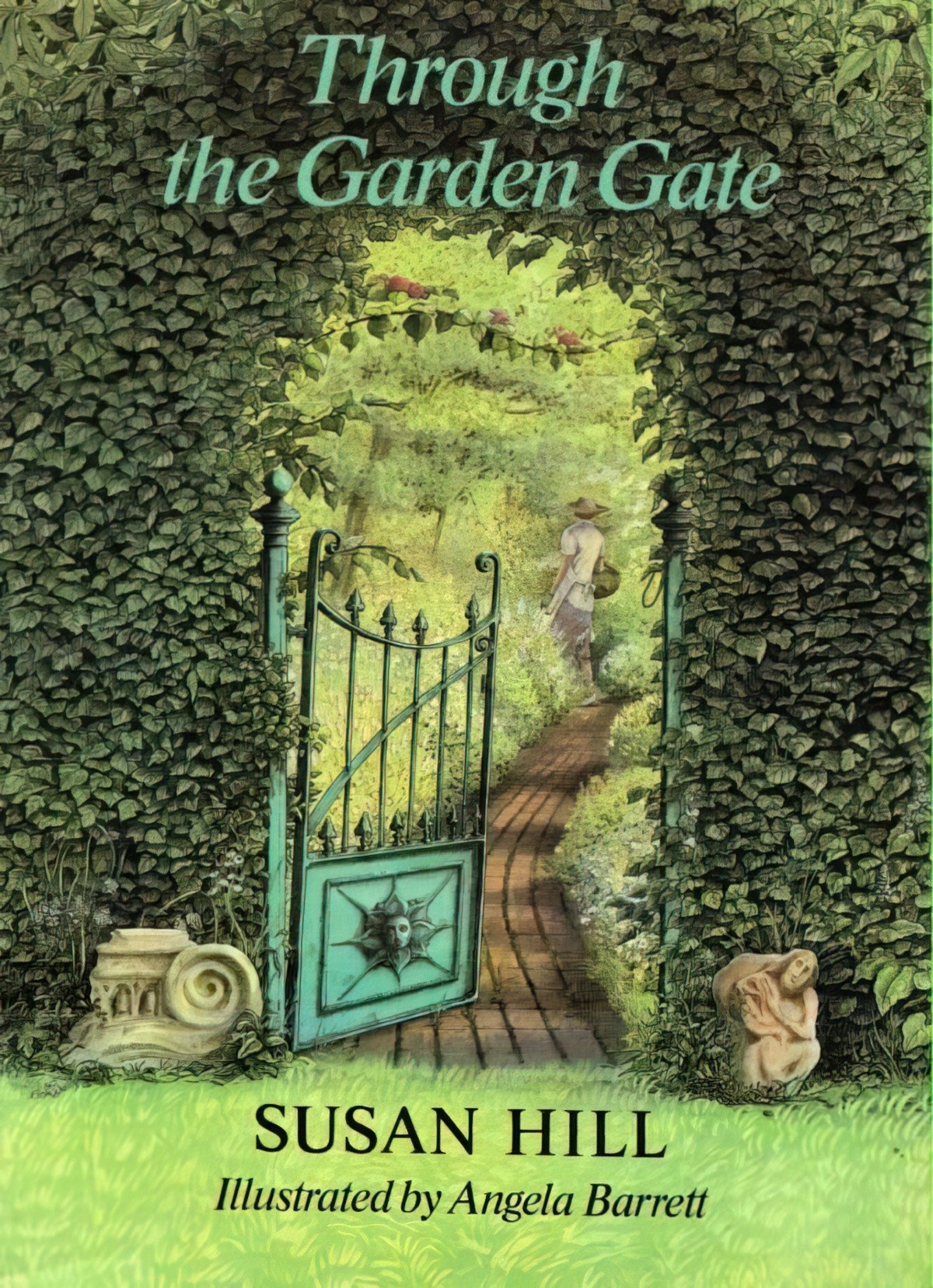

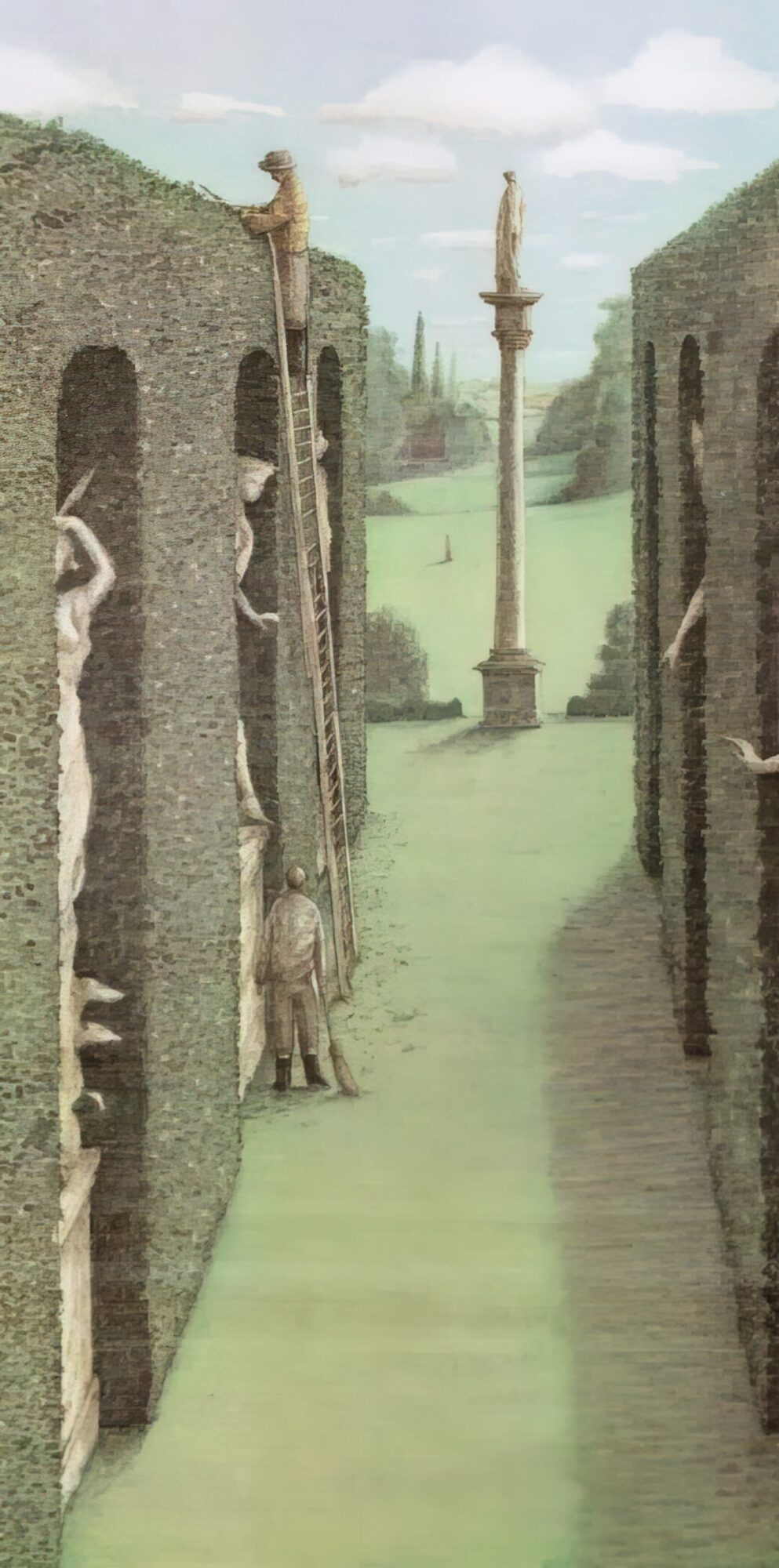

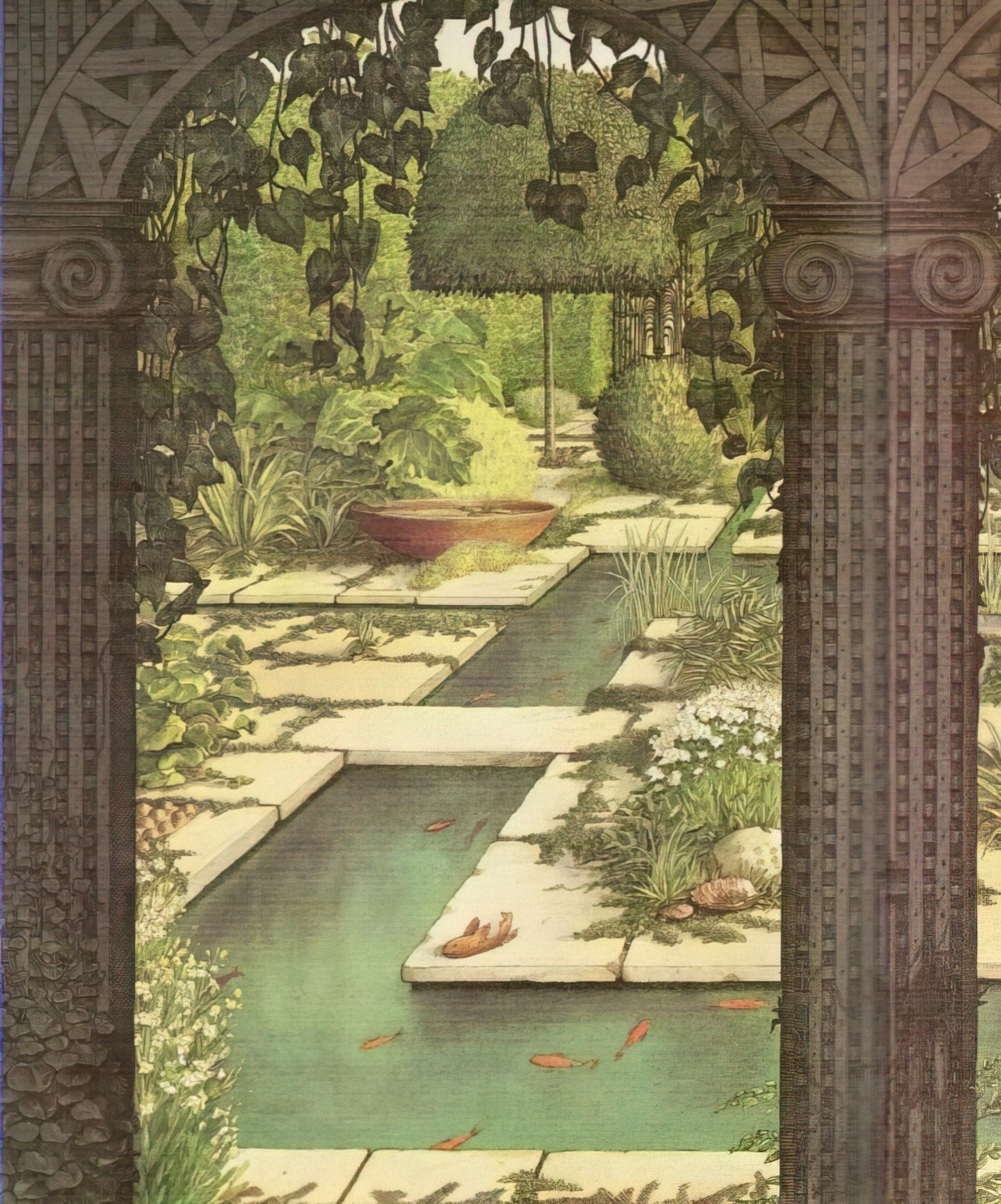

This unsettling garden can be seen in various similar artworks over the history of painting and picture book illustration. In picture books, the work of Angela Barrett and Binette Schroeder is similar in mood and style. Unlike Van Allsburg, they work in colour. For adults, take a film like Melancholia, or the earlier Last Year At Marienbad. All of these creepy gardens have been sculpted carefully by someone (or someones) yet there are no gardeners in sight. Where are they?

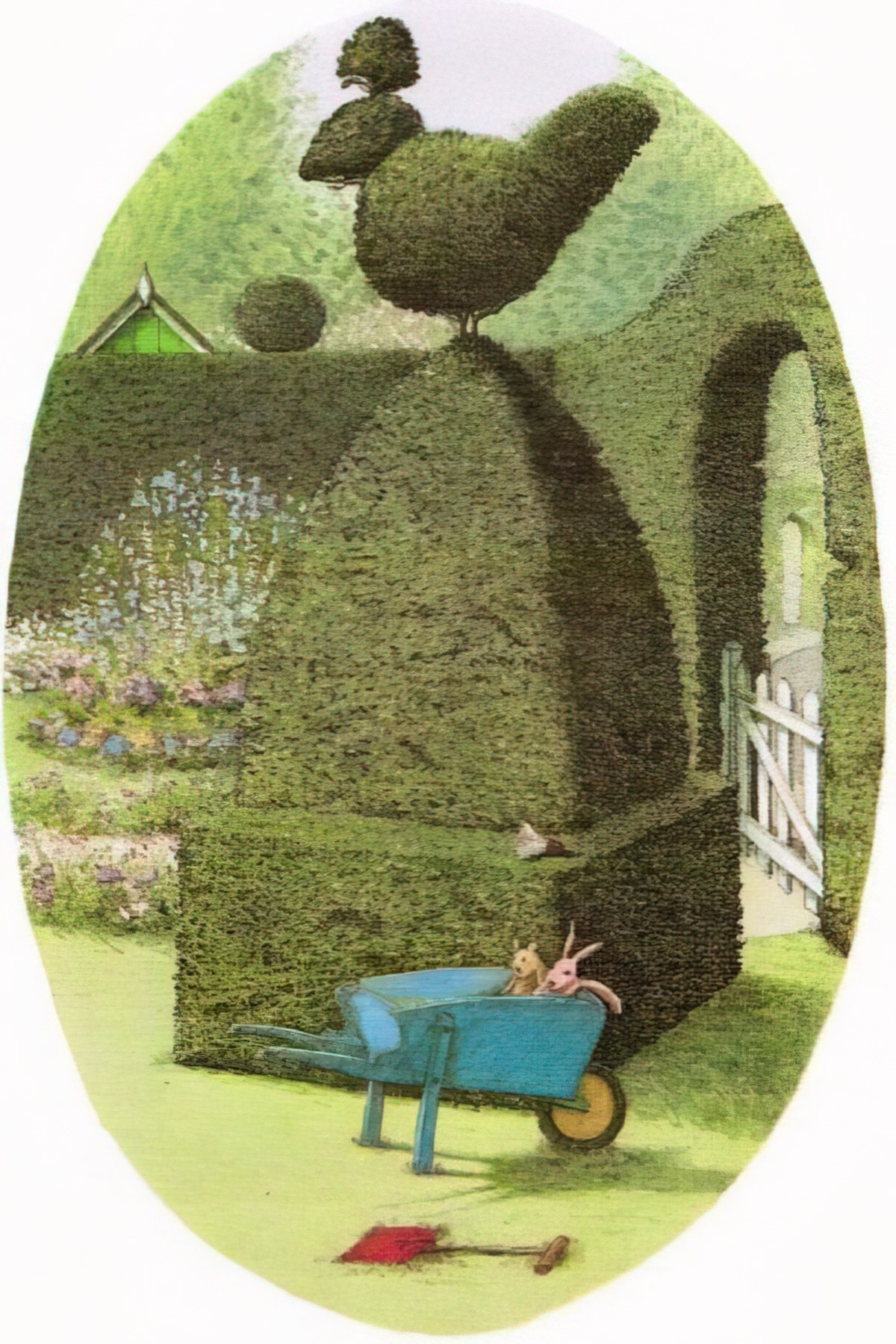

In some pieces, the shrubbery has been sculpted to look like it comes alive at night, perhaps as a larger-than-life animal. This is surely connected to the long history of urban legends about haystacks, which do look giant creatures about to come alive, at least by moonlight. Humans have long suspected bushes of wrongdoing, not because cryptobotany is a thing, but because other humans can hide behind them. If you’ve ever walked alone at night, you’ll know the fear of bushes.

There is something inherently lonely about these unsettling, symmetrical gardens, also experienced when looking at an Edward Hopper painting. Humans are at our most vulnerable when we are alone. Leave us alone for long enough and we even start hallucinating threats. We feel we are being watched.

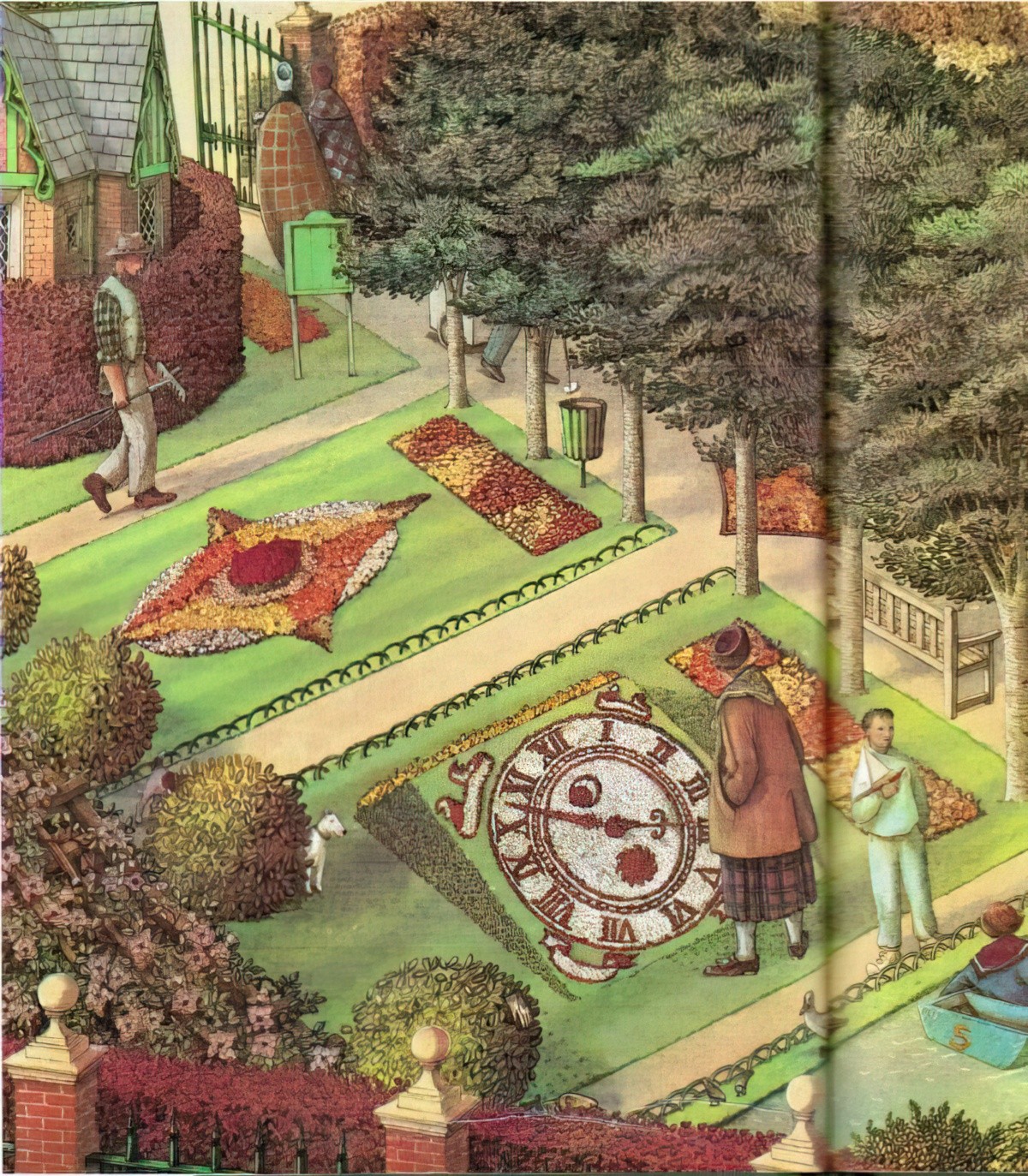

Illustrations below are from Through The Garden Gate by Susan Hill, illustrated by Angela Barrett (Hamish Hamilton Ltd, London 1986).

Last Year At Marienbad 1961

The manicured gardens in the artworks above are perhaps also disturbing because this is nature (the symbolic forest) tamed by humans. Followers of some world religions are told that to interfere with nature is to invite disaster cf. the sinking of The Titanic.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE GARDEN OF ABDUL GASAZI

PARATEXT

THE GARDEN OF ABDUL GASAZI, the imaginative Van Allsburg tale of a boy, a dog, a duck, and a nasty old magician.

MARKETING COPY

The marketers are clearly going for a Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe trinity.

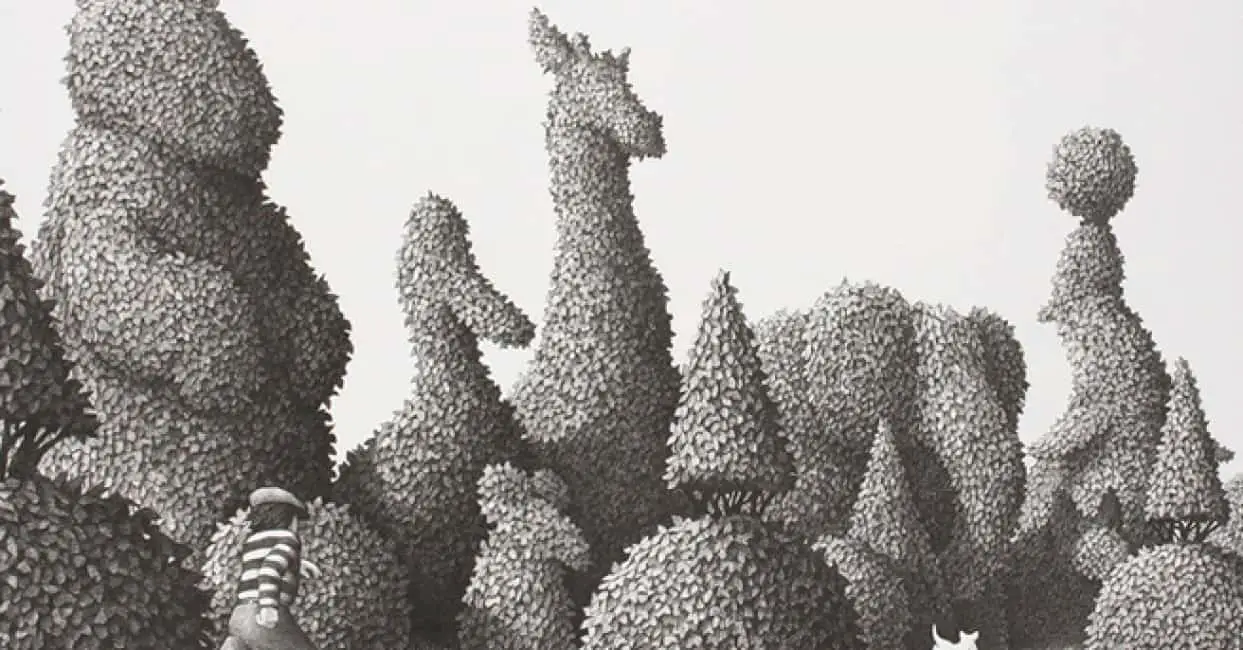

A number of consumer reviews express disappointment that the image on the cover does not seem to appear in the story, specifically the hedges shaped as animals. Perhaps readers were expecting those to come alive? Of course, adult readers are conditioned to expect the cover of the story to be a scene within:

The covers of picturebooks signal the theme, tone, and nature of the narrative, as well as implying an addressee. Few artists create a unique cover picture not repeated inside the book. The choice of cover evidently reflects the importance attached to the particular episode.

from How Picturebooks Work by Maria Nikolajeva and Carole Scott

SHORTCOMING

This kid is the Every Child (male, white), with no individuating characteristics (no moral shortcoming, no psychological shortcoming). He arrives in statu nascendi onto the page. Indeed, the story opens in medias res, without the ‘Once upon a time’ we may expect from a fairytale setting:

Six times Miss Hester’s dog Fritz had been bitten dear cousin Eunice.

This would have to be one of the most unusual grammatical constructions I’ve encountered in a picture book, let alone in the elevated position of ‘opening sentence’. I had to read it a couple of times before I understood the meaning. Normally, in my variety of English, the ‘six times’ would be tacked on at the end of this sentence, but Van Allsburg opens the entire story with it. The phrase ‘six times’ therefore becomes more important than it would otherwise. Why? (I have no answer. Perhaps someone else does.)

Everything is foreign to me in this vital opening sentence: Who is Miss Hester? Who is this dog? Whose cousin is Eunice? Three characters are introduced in quick succession. Do I have to remember these names? Van Allsburg is quickly getting rid of the mother figure so the boy can have his own adventure. There’s a long history of this in children’s stories.

THE MEDITATIVE STATE OF VERSO/RECTO TEXT/ILLUSTRATION

The illustration on the recto side of the page doesn’t offer much in the way of help when interpreting this (clunky?) opening sentence, because we see the back of a woman, a dog and… some kid. Herein lies a feature of picture books in this layout (verso text, recto illustration) with this particular text to illustration balance — there is a difference between reading this book yourself and having it read to you.

Normally I read a book myself. But in this case I had it read to me in a YouTube video and I noticed the experience was different: While someone else was reading the text, I was reading the pictures. Each of these illustrations illustrates the end of the text on the verso, so while you’re looking at the illustration, you’re concurrently conjuring a scene which is not illustrated at all. To take the opening page as an example, I’m conjuring an image of cousin Eunice being bitten by a dog, but I’m looking at a woman walking down some steps, facing away from a boy and a dog. In this way, I’m conjuring for myself a large chunk of the story. This is what we all do when reading a picture book.

There’s a long history of this practice. When researching the narrative structure of miracle stories I learned that in medieval times, the practice of using your mind to voice another prayer while reciting a standard prayer was recommended as the most effective way of praying. Today, I believe we’re more likely told to unify disparate thoughts as a way of entering the desired meditative state, so it’s fascinating to learn that this wasn’t always the advice. Reading the pictures of The Garden of Abdul Gasazi while having the text read to me lulls me into this medieval European version of a meditative state.

HAT SYMBOLISM

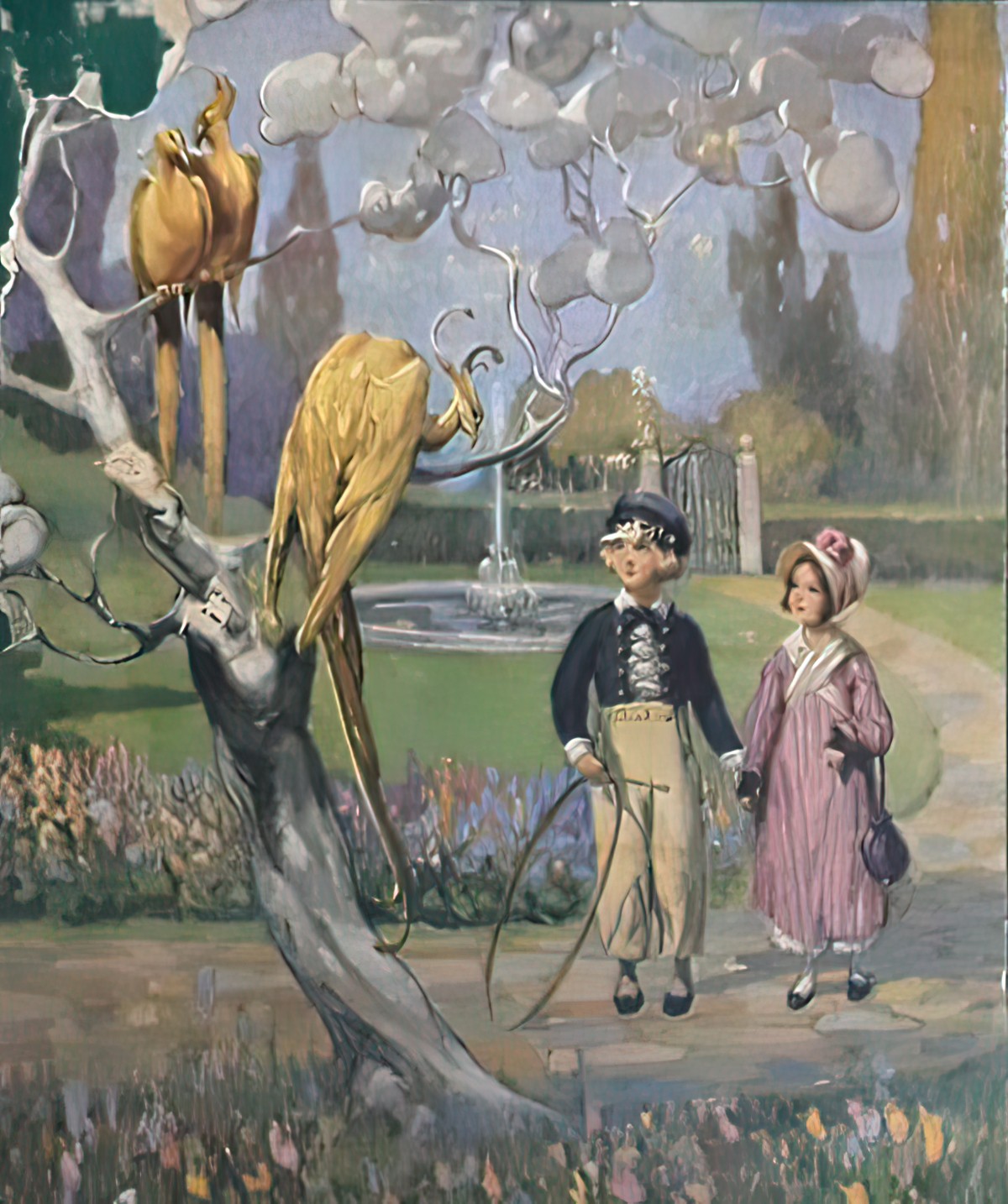

One way Every Boys are sometimes individuated: by their hats. The boy wears a hat I’d associate with a much earlier time than the 1970s. The boys in the fin de siecle painting below are wearing similar hats.

The hat in this Van Allsburg story is of course important to the plot. But is it also symbolic? Hats can do a number of things in story. Commonly they identify and confer status. In the postmodern picture book by Anthony Browne, Voices In The Park, the bowler hat carries the meaning of ‘patriarchy’ and also repression. (The boy has no choice but to follow his prescribed fate; biology as destiny.)

I feel the hat of this particular story is a removal of repression; in this case, ‘repression’ refers to the repressive thinking which leads to us believing what we see and what we are told. (But then there’s a twist at the end.)

DESIRE

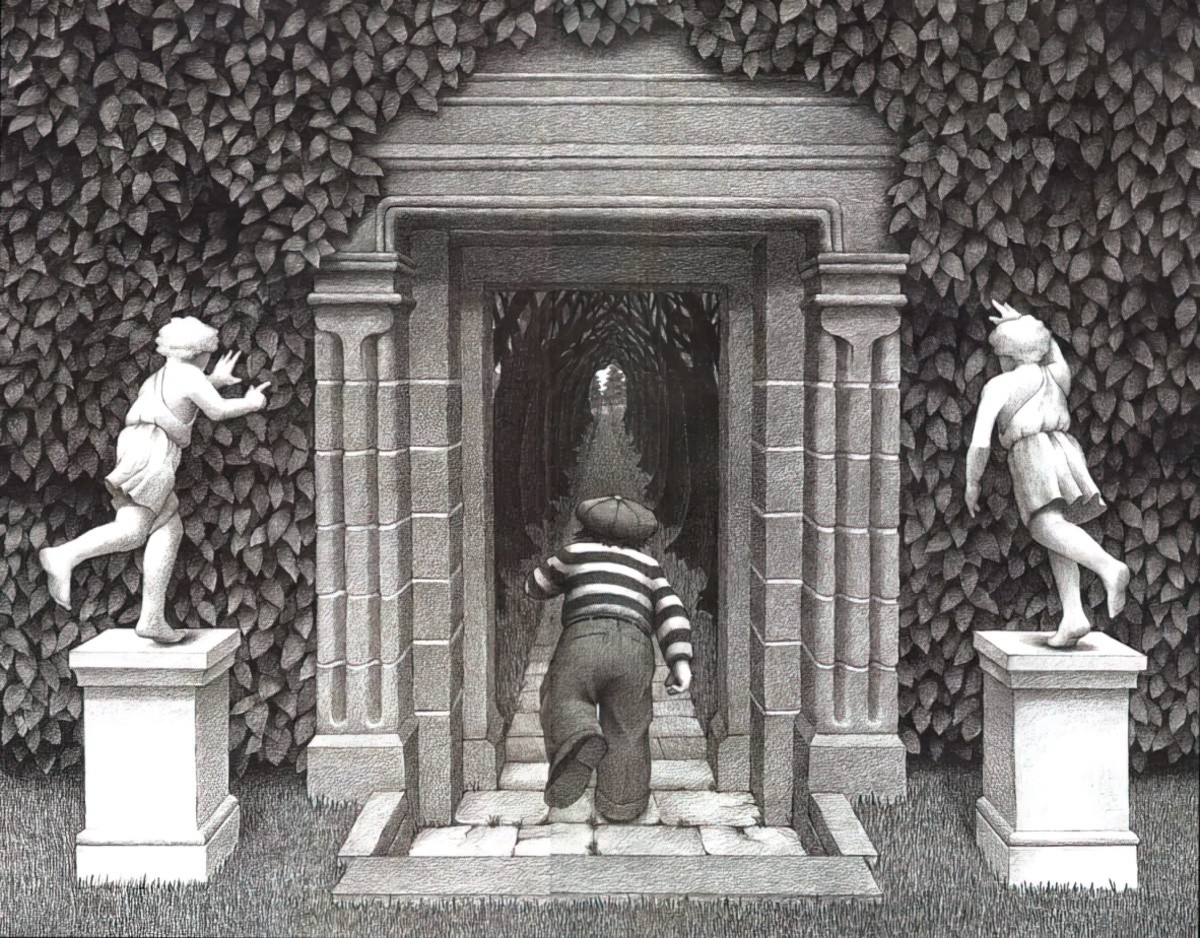

Allan wants to do a good job of looking after the dog. In the opening scene, where he guards the dog like a faithful sentry despite the dog’s dubious behaviour, we know that this is a kid who will go to the ends of the earth to do his duty. The pointing statues below lead this boy to his ‘destiny’ as if by the force of a puppeteer.

One thing storytellers often do when utilising fantasy portals: They keep their character inside the portal for a good while. Unless this happens, the reader can become discombobulated (in a bad way). How to achieve this in a picture book? Van Allsburg gives us not one but two portals. First there was the bridge, now there’s a tunnel.

OPPONENT

Insofar as pets can be opponents by running off, Fritz is the boy’s first opponent. Notice how the dog’s name rhyme’s with the boy’s: Alan Mitz has been chosen to look after a dog called Fritz. Should we consider this dog the boy’s familiar?

The name Abdul is common in Middle Eastern cultures:

Abdul … is the most frequent transliteration of the combination of the Arabic word Abd (عبد, meaning “Servant”) and the definite prefix al / el (ال, meaning “the”).

Wikipedia

However, the name Gasazi appears to be entirely made up for the purposes of the story. Cormac McCarthy utilised the same trick when naming Anton Chigurgh for No Country For Old Men. McCarthy aimed to keep his sociopathic baddie foreign, but not tied to any particular country or culture.

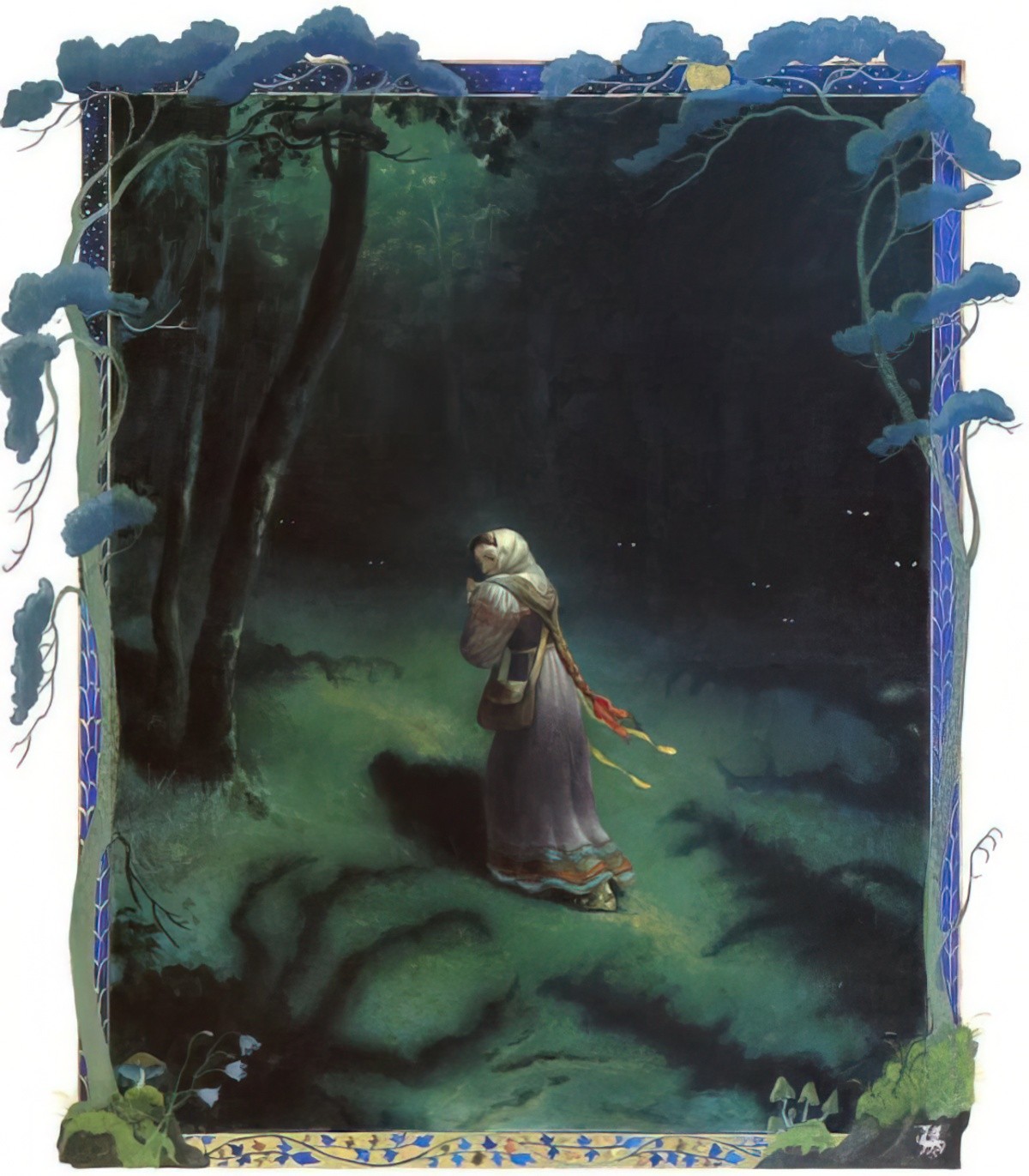

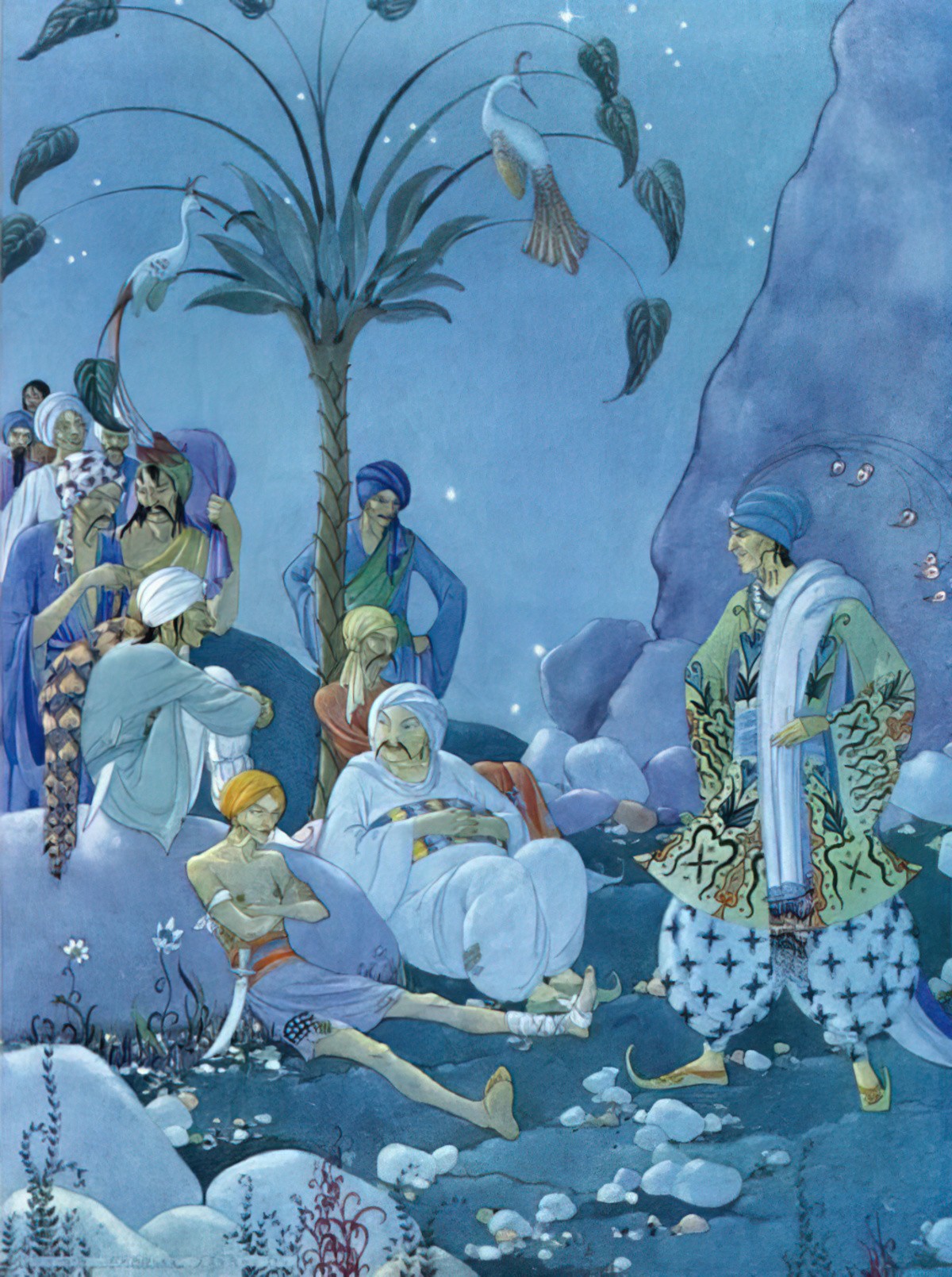

There seems a clear link to the Arabian Nights tradition expressed on the pages of Abdul Gasazi. The tales of the (1001) Arabian Nights, once adapted for English speaking audiences, became a Western notion of the mythical Middle East rather than an unadulterated importation of Middle Eastern folklore. (There is always modification to stories when they travel.) When early Western audiences encountered those tales ostensibly from Arabia, they probably knew little else about thd place, and their ideas of the real Middle East became mythical. Beautiful, sculpted gardens featured large in illustrations from an earlier Golden Age of children’s literature. Notice also that birds are an important feature of The Arabian Nights:

PLAN

Driven by the need to look after the dog, the boy follows it. He ends up at a magnificent house, sort of like a magical house in the middle of a forest. (Notice how this house has its own mini fantasy portal tunnel.)

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Inside the house is where boy and man come face to face, literally, as depicted in the illustration below. The shadows of this image are particularly interesting. The main light source comes from somewhere off-page and if we count boy and shadow as one thing, he seems a lot more formiddable than he feels. The magician’s shadow falls onto the wall and is therefore absent from our view. A doorway stands between them in the background, leading into mysterious darkness. How will the magician react to the boy’s apology and request? Well, for now that remains a mystery.

In the next part of the boy’s struggle, the magician tells the boy he has turned his dog into a duck and there’s no knowing when or if the dog will come back as a dog.

ANAGNORISIS

When the boy returns to Miss Hester’s, it seems the dog has been safely at home in the yard rather than lost in the mysterious Mr Abdul Gasazi’s garden. The revelation comes (for the reader, not for the boy) when the dog gives Miss Hester a hat. Miss Hester doesn’t know where the hat came from, but the young reader will. This ironic gap makes young readers feel smart, and you always want to leave them feeling smart as they’ll develop a love for reading and books. I guess this is why it’s not the boy himself who discovers the return of the hat.

NEW SITUATION

So, is there magic in the world or not? In interview, Chris Van Allsburg will admit to this aim: His stories serve to help young people retain a sense of wonder and magic about the world.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

I’m not personally a fan of this ideology. I don’t want young readers to wonder if there’s magic in the world. However, I do want young readers to retain their sense of wonder, to question what adults say to them, and to acknowledge that not everything can be explained (yet).

But when things can’t be explained, that’s not because the world runs on magic. It’s because science isn’t there yet. If we consider that specific form of wonder ‘magic’, then fine, I guess. My unease perhaps comes from a plot in which a boy successfully learns not to believe wacky old men spinning unlikely stories, then flips right back to a plot with a different hermeneutic closure: that wacky old man spinning the unlikely story is proven right. The existence of the hat (fairy cup) in the veridical story world proves it. Silly woman, using the logic of realworld physics, trying to convince a kid magic ain’t real…

THE FRIDGE TEST

After reading this story a few things disturb me. The first is that this is a dangerous dog, and a breed which can be very dangerous with the wrong companion. If this dog has bitten someone six times, why on earth is Miss Hester leaving a kid to look after the damn thing?

(Van Allsburg inserts this dog into every picture book he creates.)

If the magic place is ‘real’, and we are told that it is, then why has she not told the boy about the massive weirdo living on the estate next door?

The biting incident described in that opening sentence is clearly a McGuffin, designed not to get the plot going exactly, but to establish the mood: A sense of foreboding.

Honestly, I think a story illustrated as beautifully as this one can get away with a slightly problematic plot and will still be loved by many.

I believe the boy who falls asleep on the couch never wakes up and dreams teh eentire thing until Miss Hester arrives home. While he was asleep, the dog nicked his cap (which he falls asleep wearing). Notice the framed picture above the sofa, depicting a bridge, with tall trees on one side. This image likely served as fodder for the kid’s cheese dream.

RESONANCE

My distaste for fairy cup endings in modern children’s stories isn’t widely shared. The ambiguous magical ending worked so well for book-buying audiences that Van Allsburg reused it, notably in The Polar Express, another great success. American book buyers clearly love stories which teach that magic (or any kind of unlikely freakin story) could be real.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

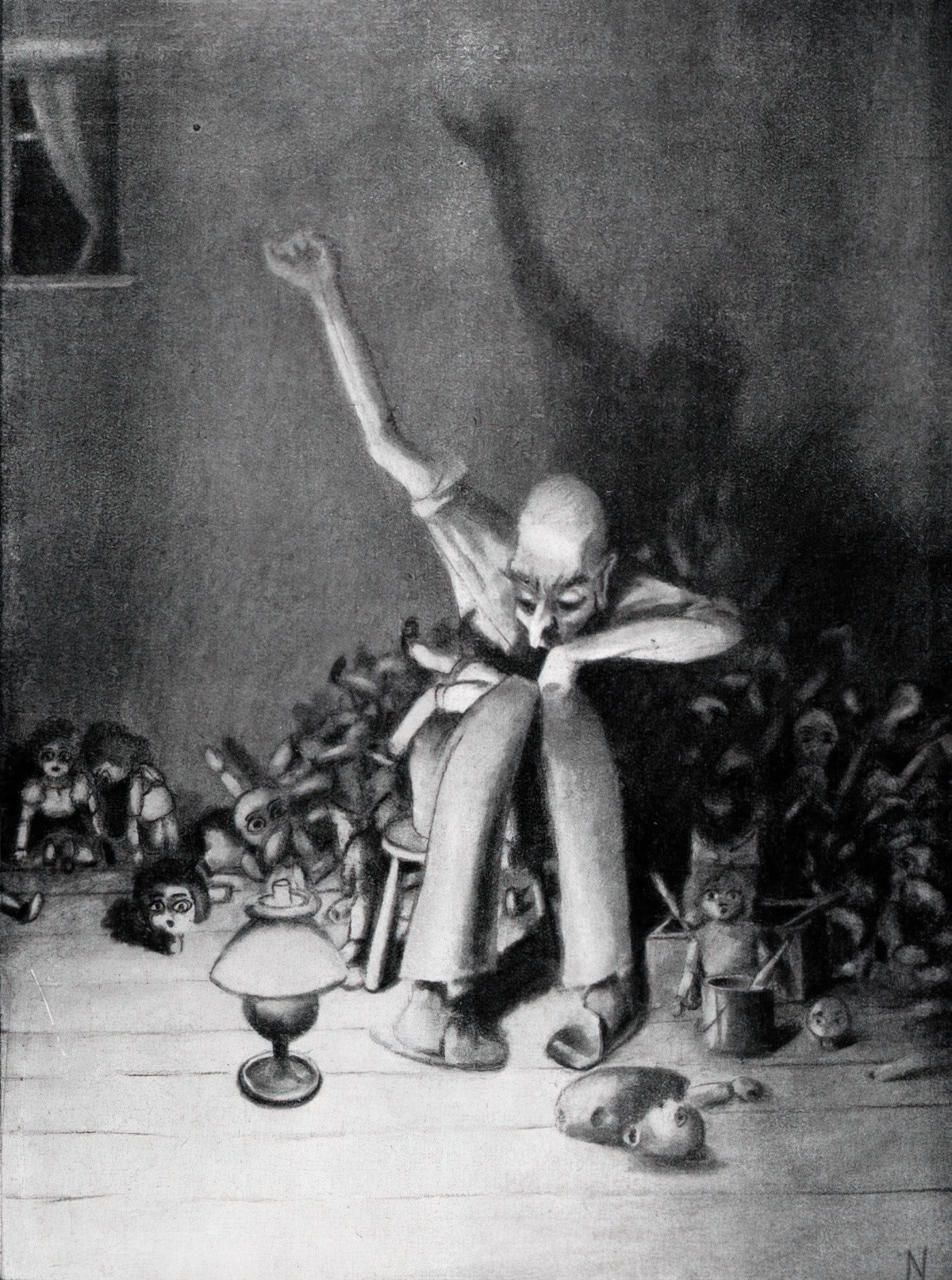

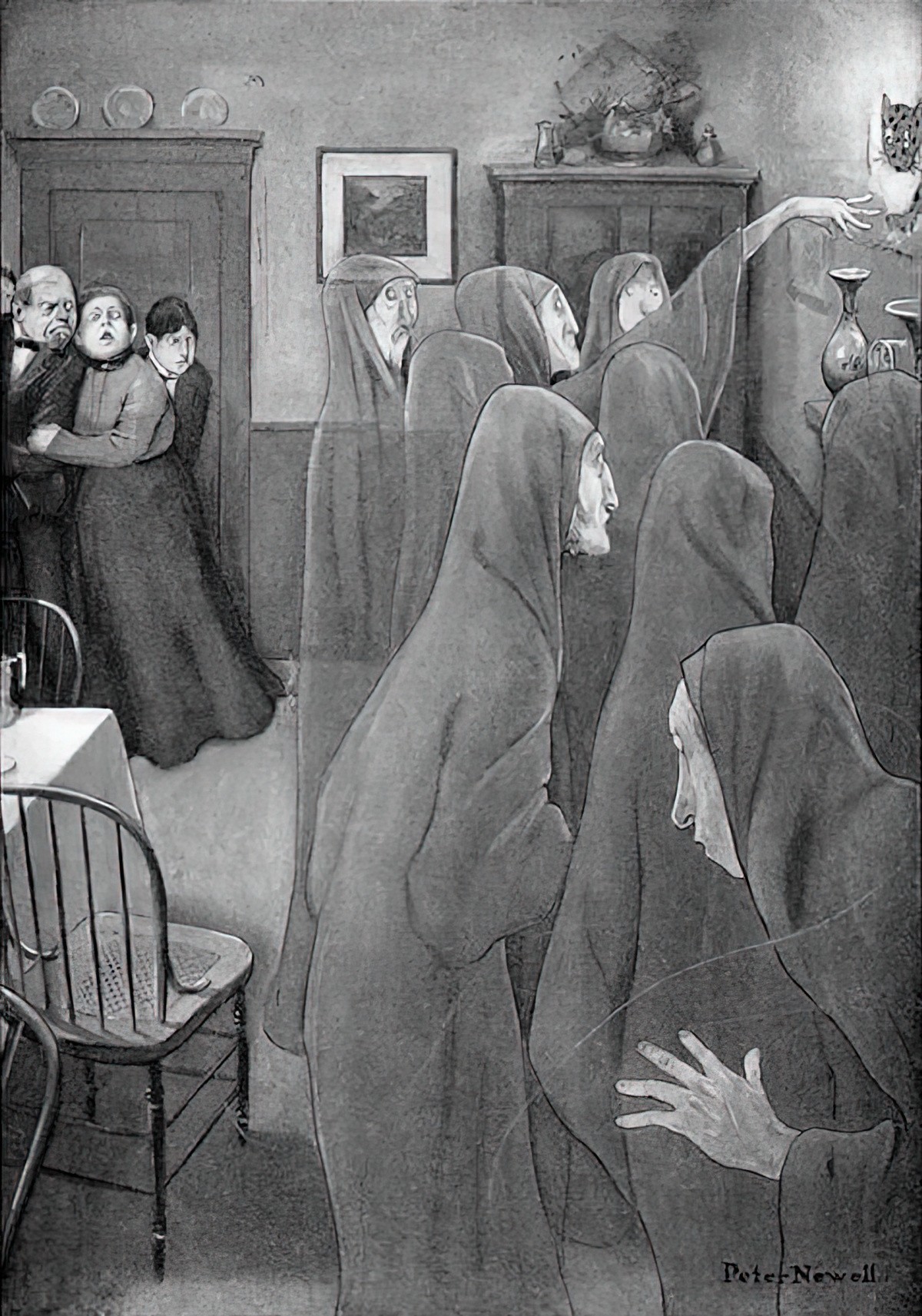

If you enjoy the pencil drawings of Chis Van Dusen, you will probably also enjoy the art of German painter Otto Nückel (1888-1955). He is best known as one of the 20th century’s pioneer wordless novelists, along with Frans Masereel and Lynd Ward.

Otto Nückel (1888-1955)

The pencil work of Theodor Kittelsen can also sometimes look like Chris Van Dusen’s style.

When graphite pencil is rendered in this way the result is similar to the artwork achieved by artists creating with stone lithography.

Believe it or not, the early work of iconic American illustrator Norman Rockwell looks a little like the art of Chris Van Allsburg.

Also check out Eric, a contemporary picture book by Australian Shaun Tan, with similar pencilwork.