“Gallatin Canyon” is a short, grim road trip story by American author Thomas McGuane. This story served as the title of McGuane’s 2006 collection. In 2021, Deborah Treisman and Téa Obreht discussed its merits on the New Yorker fiction podcast.

SYNOPSIS

A man and a woman drive through Gallatin Canyon, toward Idaho, where the narrator (the man) intends to use his obnoxious guile to undo a business deal. “I’m a trader,” he tells his companion, on what will be their last day together. “It all happens for me in the transition. The moment of liquidation is the essence of capitalism.”

Stephen Metcalf, 2006

McGuane’s first collection in twenty years.

Place exerts the power of destiny in these ten stories of lives uncannily recognizable and unforgettably strange: a boy makes a surprising discovery skating at night on Lake Michigan; an Irish clan in Massachusetts gather at the bedside of their dying matriarch; a battered survivor of the glory days of Key West washes up on other shores. Several of the stories unfold in Big Sky country, McGuane’s signature landscape: a father tries to buy his adult son out of virginity; a convict turned cowhand finds refuge at a ranch in ruination; a couple makes a fateful drive through the perilous gorge of the title story before parting ways. McGuane’s people are seekers, beguiled by the land’s beauty and myth, compelled by the fantasy of what a locale can offer, forced to reconcile dream and truth.

The stories of “Gallatin Canyon” are alternately comical, dark, and poignant. Rich in the wit, compassion, and matchless language for which McGuane is celebrated, they are the work of a master.

CONTEMPORARY WESTERNS

Obreht notes that there has been a renewed literary interest in the American West. However, this time around around Western fiction tends to be by writers who themselves come from the West. Thomas McGuane moved to Montana in the late 1960s.

I’ll add that contemporary Westerns are technically, almost without exception, anti-Westerns and have been anti-Western since WW2.

What makes them ‘anti’? While Western stories of all kinds are deeply connected to landscape, the old-school Westerns glorified expansionism, whereas the anti-Westerns of today highlight the harsh and unforgiving landscape. Anti-Westerns minimise the significance of humans, who are now depicted as temporary fascinations on a vast landscape. Death is a constant spectre.

That said, expansionism is still a thing. Now it’s called development, or our ‘rapidly changing world’.

Louise was a lawyer, specializing in the adjudication of water rights between agricultural and municipal interests. In our rapidly changing world, she was much in demand.

“Gallatin Canyon”

CHARACTERS WITH INCHOATE PLANS

“Gallatin Canyon” also interests me as a short story because writers are often advised to give main characters plans. Sure, things happen in stories to stymie the best-laid plans, but writers are frequently told their characters must make plans anyway, then change them as the opponent steps in to mess things up. Otherwise, we are told, stories suffer from poor pacing and unsatisfying drive, starring annoying characters who lack get-up-and-go.

The problem is, in real life there are people whose characters and lives fit exactly that description. In fact, this probably describes most of us at some point in our lives. Don’t poor planners deserve to see themselves in stories, too? Well sure, although only lyrical fiction seems to have time for this kind of mimesis. (Genre fiction goes by different rules.)

The main character of “Gallatin Canyon” does have a plan, of sorts, but because he is insufficiently self-aware, his plan is only partially formed. This short story serves as a great case study in how to write a character with inchoate plans. Sure enough, inchoate plans come back to bite us in the bum.

AN EXPLORATION OF MALADAPTIVE MASCULINITY

Here’s another thing that makes this an anti-Western rather than a Western per se: old-school Westerns glorified a certain type of masculinity. Contemporary anti-Westerns are far more likely to critique than glorify that old cowboy style of bravado and jostling for hierarchy. I spent the first half of this story irritated to be in the company of the main character of “Gallatin Canyon”. What saves it is the narrative choice, which leads me to the climax, in which we get our critique.

McGuane writes about men, and he often writes about men in the American West; and so he’s thought of as a writer of manly-man reticence in the school of Hemingway, beautified with dashes of Big Sky coloring. […] And for all its propensity to macho wandering, “Gallatin Canyon” is where Frederick Jackson Turner’s well-traveled cliché, about the openness of the American frontier and thus the American character, has come to die.

Stephen Metcalf, 2006

Metcalf also writes that American manliness and American loneliness are one and the same.

SETTING OF GALLATIN CANYON

You can write about a place but it takes something else to be a writer of a place. McGuane is a writer of the American West.

Téa Obreht

PERIOD

The first person narrator is writing this story one (rodeo) weekend in the early 2000s but he is looking back on himself as a young man. My take is that he was 20 or 30 years younger, suggesting the 1970s or 80s. McGuane wrote this story when he was in his mid 60s.

Téa Obreht has noticed a tendency in modern literature for older narrators looking back at their younger selves to sneer at how they used to be. This story avoids that despite showing the absurdity of the young man’s situation. This is a humane rather than a sneering story, representative of McGuane’s later work in general.

DURATION

Most of this story takes place over the course of a single day, with a brief postscript type of ending which takes us a few months into the future, but not into the present of the narrator’s current life. (We’ll never find out what his life looks like now.)

LOCATION

The first sentence in a work of fiction places the first limitation on the utterly limitless world of the author’s imagination.

Alice McDermott

McGuane places is in space in the first sentence:

The day we planned the trip, I told Louise that I didn’t like going to Idaho via the Gallatin Canyon.

“Gallatin Canyon”

This story rewards those with a knowledge of Montana and Idaho geography. I’m limited to what I can see on maps. This is the route they don’t take due to repairs:

ARENA

The opening paragraph continues:

It’s too narrow, and while trucks don’t belong on this road, there they are, lots of them. Tourist pulloffs and wild animals on the highway complete the picture. We could have gone by way of Ennis, but Louise had learned that there were road repairs on Montana Highway 84—twelve miles of torn-up asphalt—in addition to its being rodeo weekend, and “Do we have to go to Idaho?” she asked.

“Gallatin Canyon”

Notice also that the author sets up the emotional expectation of this story when he writes “we could have gone (by way of Ennis)”, foreshadowing the fact that this is ultimately a story about regret.

The narrator has a home in a place nearby called Sourdough.

On their journey south along Highway 191, they move through places called Storm Castle, Garnet Mountain, Ashton, St. Anthony, Sugar City, Rexburg, Wilford, Newdale, Hibbard, Moody, Hog Holly Road, France, Squirrel.

Another mythical journey in which place names are scattered into the the short story like this is “Beer Trip To Llandudno” but Kevin Barry. Both of these short stories are daytrips. Listing place names in this way, with brief descriptions and the odd detour is a great way to pace what we might call a ‘daytrip’ short story.

The signficance of stories set over single days in lyrical short stories? They frequently leave us with this thought: Life can alter its path in the space of a single day.

MANMADE SPACES

The first person narrator owns a small car dealership in ‘the sleepy town of Rigby’.

Four Corners was filled with dentists’ offices, fast-food and espresso shops, large and somehow foreboding filling stations that looked, at night, like colonies in space

“Gallatin Canyon”

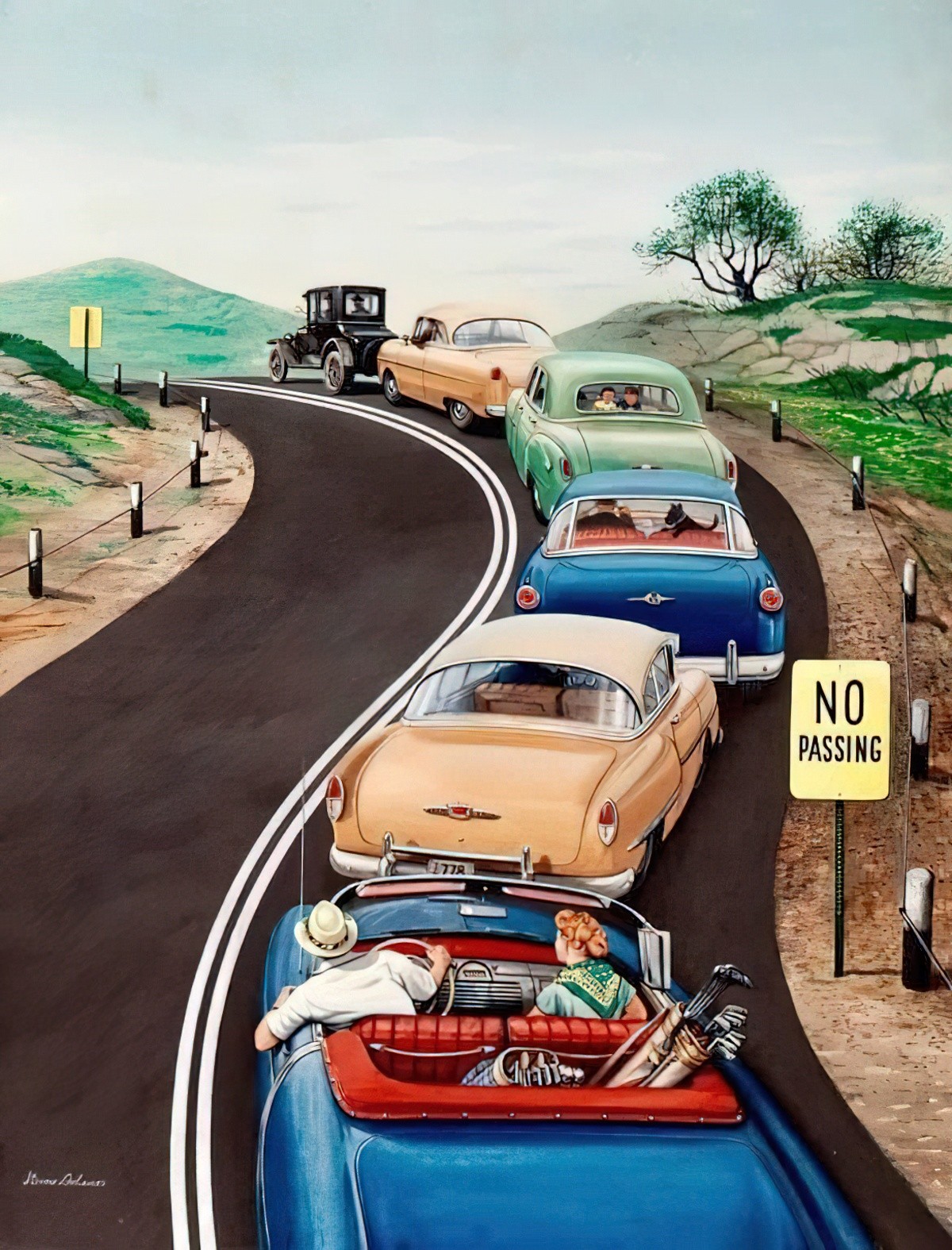

Most of this story takes place on a highway, which I argue is the manmade analogue of a river, as both are about fate and entrapment. This story is a home-away-home journey split into two clear parts: The journey there and the journey home. Children’s literature offers the clearest examples of this structure. See The Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson and The Enormous Crocodile by Roald Dahl. The story doubles back on itself at around the midpoint, and sometimes mirrors itself. The mirroring structure emphasises how different a trip along the same path can be. There’s generally a shift in emotional valence.

NATURAL SETTINGS

Whenever a lyrical short story involves a canyon, you can be sure the author is going to make metaphorical use of it. Here it is, the Gallatin Canyon in West Yellowstone:

Rivers have many symbolic uses in story, and in some ways they are equivalent to highways. Both can symbolise fate. Once you’re on a river/highway you’re inevitably headed towards some end goal. One can’t simply back out. Even the way we talk about highways utilises the language of waterways:

We joined the stream of traffic heading south, the Gallatin River alongside and usually much below the roadway, a dashing high-gradient river with anglers in reflective stillness at the edges of its pools, and bright rafts full of delighted tourists in flotation jackets and crash helmets sweeping through its white water.

“Gallatin Canyon”

Rivers have inherent danger to them. Stories such as Deliverance utilise this danger to the full. In this highway story, McGuane foreshadows the danger of the highway, emphasising the way in which a stream of traffic entraps you in much the same way as a strong current. Although it’s technically possible to swing a U-ey and turn a vehicle around at any point, the experience of being on a congested highway is more like the experience of being caught in a rip:

This combination of cumbersome commercial traffic and impatient private cars was a lethal mixture that kept our canyon in the papers, as it regularly spat out corpses. […] A single amorous elk could have turned us all into twisted, smoking metal.

“Gallatin Canyon”

The road stretched before me like an arrow [another fatalistic symbol].

“Gallatin Canyon”

Whenever you’ve got a canyon foregrounded in a story you can bet a good lyrical writer will symbolic use of it. (See, for instance “The People Across The Canyon“.) A canyon has a precipitous drop. It is also a landform equivalent of any kind of lacuna.

This story is about a couple who might be romantic, but who are detached. Louise is self-contained, has her own law practice and a past marriage which she has fully recovered from. She doesn’t need him. (Perhaps she doesn’t need anyone.)

The main character is also trying to close a deal and to create a gap between himself and the current contracted buyer. There are metaphorical canyons all over this story. Watch out for ‘gap’ synonyms such as ‘chasm’:

I didn’t mind equal billing in a relationship, but I did dread the idea of parties speaking strictly from their entitlements across a chasm.

“Gallatin Canyon”

Then there is the ironic gap between what the young narrator can see about himself and what the astute reader can understand about him. Unlike us, the young narrator is unable to make connections. For example, there’s a moment during the drive when he says he’s reminded of a failure back in Rigby but he is unable to put his finger on it. In this way, landscape connects directly to character.

WEATHER

West Yellowstone seemed entirely given over to the well-being of the snowmobile, and the billboards dedicated to it were anomalous on a sunny day like today.

“Gallatin Canyon”

More important than the weather in this story, which we assume is sunny and unremarkable: The shift from daytime to night-time, when the story turns dark and dangerous.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

The vehicles are important to “Gallatin Canyon”. Not only does the climactic event include vehicles, but the first person narrator also sells them. I’m not sure if I’m supposed to consider the cars in this story more carefully because of that connection, but if we go back to the first paragraph, in which the author emphasises the route he didn’t take, it’s clear (especially when looking at a map) that there was a much easier and more direct way of achieving his goals that day. He seems to feel that if he had driven the short route (despite the roadworks) his entire life would have panned out differently.

The narrator is also fixated on those billboards about snowmobiles. He sees a juxtaposition between the snowy imagery of the promo material around Gallatin Canyon and the sunny day upon which they’ve arrived. Is this the author signalling to readers that we are to be on the lookout for other juxtapositions ourselves?

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

The narrator mentions that it’s rodeo weekend. I think this provides verisimilitude, and an added reason for the congestion around West Yellowstone, but also reminds the reader that we are reading a contemporary (anti-)Western.

Although the West is fully explored by this point in American history, this guy is still very much a modern cowboy in that he is involved in his own version of expansionism, ostensibly in reverse: He’s hoping to avoid closing the sale on a car dealership he already owns, because he’s got a far better offer elsewhere. This argument he’s about to have with the first buyer is the contemporary equivalent of a gunfight on Main Street.

Like short stories by Annie Proulx, there’s a conflict in this one between the reality of nature and the way humans try to manipulate natural resources which refuse, ultimately, to bend to our will:

“You should be in my world,” Louise said. “According to the law, water has no reality except its use. In Montana, water isn’t even wet.

“Gallatin Canyon”

STORY STRUCTURE OF “GALLATIN CANYON”

On the New Yorker Fiction podcast it is remarked that, “There’s a sense of space and time closing in around [the main character]”. This suggests a story in the shape of a vortex.

SHORTCOMING

The main character is of the economically fortuitous generation and has ‘caught the upswing in our local economy—cars, storage, tool rental, and mortgage-discounting’. Téa Obreht uses an interesting word to describe this first person narrator: ‘narrative consciousness’. (This is a handy word to use when we don’t need to emphasise whether this story is told in first, second or third person.)

There is a clear difference between our main character’s imaginative landscape and how he perceives it. He thinks he has more control over his situation than he really does. (This isn’t the only guy in the stories of this collection to think that; Faucher in “Old Friends” also has this problem, and in aggregate it is clear that McGuane is creating men who overestimate their own charms as a generally problematic aspect of cowboy masculinity.

This story serves as commentary on the cultural messaging that men get (and got even more strongly last century): That as long as a man tries hard enough and persists, he can persuade any woman to be his. As much as this guy respects Louise as a lawyer, he is still failing to clock her as a fully fledged human being with her own (lack of) desires and goals. Capitalism has taught him that people can be manipulated in the business world; he’s trying to bring that to the romantic table, which never works. McGuane is sure to use the word ‘capitalism’ once on the page.

McGuane communicates his main character’s shortcoming to readers by telling the story from the point of view of the callow young chap as an older, wiser man. (ie. The older, wiser first person narrator of the story has changed so much that we can now consider him an extradiegetic narrator.)

Perhaps this guy would seem less sympathetic if recounted by an unseen third person narrator. That fact that he’s looking back at his younger self with the benefit of knowing, wry hindsight, means we can sit in the same car as this wheeler and dealer whose only goal is to back out of a deal legitimately made by pissing a buyer off. He also seems more sympathetic to the reader by failing to concoct a good plan. In his imagination he fleshes out the bit where, after pissing the guy off, he takes him out for a steak. In hindsight he is also self-deprecating, which contributes to the humour of the voice:

I had this sort of absurd picture of myself strutting into the meeting.

“Gallatin Canyon”

For some reason we tend to find characters rehearsing scenes before they happen very funny. It’s always a set-up and pay-off gag because scenes in fiction don’t go exactly as they’ve been rehearsed.

I would guess this young guy isn’t very good at reading his own emotions in general. An occupational therapist might say his interoceptive skills need work. (A surprisingly large proportion of adults don’t have good interoceptive skills.)

DESIRE

The first person narrator has two goals for this trip, though he doesn’t tell us the second one until he ‘gets to know us a little’. He first tells us the business reason for the trip in the second paragraph:

I was headed to Rigby, Idaho, expressly to piss off a small-town businessman, who was trying to give me American money for a going concern on the strip east of town, and thereby make room for a rich Atlanta investor, new to our landscapes, who needed this dealership as a kind of flagship for his other intentions.

“Gallatin Canyon”

We then learn that he’s hoping to deepen the romantic relationship between himself and Louise, the woman he has invited along, though she doesn’t really want to go. (“Do we have to go to Idaho?” she asked.)

OPPONENT

ROMANTIC OPPONENT

McGuane has become our poet-philosopher of the arm’s length, of the prudently aborted intimacy that keeps both isolation and commitment equally at bay.

Stephen Metcalf, 2006

This is a love story (tragedy), which makes Louise the main (love) opponent. In the retelling of this story, Louise and the main character seem at first glance like equals in that they are both self-deprecating and have a similar sense of humour.

But here’s the sad irony: This main character would’ve made a good romantic partner for Louise… had he managed earlier to achieve the kind of knowing insight into masculinity that Louise has already achieved. She shows her reflective sense of humour here:

Bob’s from the South. For men, it’s a full-time job being Southern. It just wears them out. It wore me out, too. I developed doubtful behaviors. I pulled out my eyelashes, and ate twenty-eight hundred dollars’ worth of macadamia nuts.

“Gallatin Canyon”

In contrast, the main character narrator shows us how obsessed he is with where he slots into the hierarchy of other men in Louise’s life. He asks her if her ex is married, for instance. He wants to know he’s right out of the picture, and assumes that remarriage would be proof, or something.

I’ll point out at this stage that there’s no evidence Louise is a romantic person. My interpretation is that she may be on the aromantic spectrum. This is a seldom-considered possibility when interpreting fiction, since we live in a strongly amatonormative society. The main character, too, may be aromantic. His actions in this story indicate he feels pressure to have a culturally sanctioned romance with Louise. He exhibits no burning desire to be with her. If he hasn’t been comparing himself to those guys with the many kids (‘potato-fattened, bland opportunists with nine kids between them’), he may not have even felt less of a man for ‘failing’ to secure himself a family. As discussed on the New Yorker fiction podcast, the main character is thinking about Louise in a very transactional way.

Is this aromanticism or is it the effect of maladaptive masculinity? Impossible to say, since this cowboy masculinity requires men to quash feelings of romance.

MINOTAUR OPPONENT

So Louise is functioning as the main opponent of this story, but even ‘love’ stories require another level of opposition in order to be interesting, so the Minotaur opponent of this story is the small-town businessman the narrator is aiming to piss off: Oren Johnson.

Now, because stories often feature those two levels of opposition and still work perfectly fine, readers are all the more surprised when a third (or possibly the same?) opponent turns up later, just as we think the day is drawing to a close.

The danger of the congested highway – a metaphorical fast-flowing river – heightens the anxiety our narrator feels about his half-arsed plan to deepen his romantic connection to Louise. In this way, the environment functions as an opponent, contributing to our main character’s anxieties.

Apparently, McGuane has been asked who he intended the highway monster to be. He replied that it might be the Grim Reaper, or we might equally interpret him as the buyer of the car dealership experiencing spectacular buyer’s remorse.

PLAN

As mentioned above, the ‘planning’ aspect of this story makes for an interesting case study because we have a character with no clear plan. In fact, this will be partly what contributes to his downfall.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

The suspense level of this story really picks up at Black Butte on the journey home. McGuane has teased us into thinking that the main battle is going to occur between the narrator and the buyer he is hoping to piss off, but in that our expectations are stymied.

On the way home McGuane takes us into an American urban legend – the type where a couple is chased on a lonely highway by a headlight which turns out to be supernatural.

After a tricky manoeuvre, the main character avoids an accident but the tailgater plunges to his death in the canyon.

ANAGNORISIS

Here’s an example of how stories set in the American West are so intimately connected to landscape (manmade or otherwise): The journey to Rigby is congested. Although these characters take the same route home, the highway is completely different this time. The pair are now isolated. The highway itself reflects the changed emotional state of our romantic opponents. Why do they take the same route home? Téa Obreht suggests that perhaps there’s an attempt to recoup where they were that afternoon – a more promising emotional space. But ironically, what lies at the end of it is even worse than the discomfort of earlier in the day.

Here’s the thing about stories told by first person narrators in hindsight: The self-revelations are dripped throughout the text:

I reflected on the pathos of ownership and the way it could bog you down.

“Gallatin Canyon”

Good fictional dialogue contains an unsaid layer. At the climax of this story Louise tells the narrator she wishes she could feel something. She is clearly talking about her relationship with the main character as well as the guy who flew off the cliff into the canyon.

Louise is revealed in this moment to be another person who can’t make connections particularly well, either. The connection she is making is between the unpleasant day and this horrific event. This is the connection that she will dwell upon. She may realise that she, too, is a bit lost.

Our narrator should learn in this moment that Louise doesn’t want to marry him, but doesn’t quite believe it at the time. He’s going to persist a while longer. Only in hindsight does this extradiegetic self understand that they were never meant to be.

McGuane utilises a form of dramatic irony by creating a gap between what the reader understands and what the young narrator fails to understand at the time of this story: We know all along that Louise isn’t interested in marrying him.

“Gallatin Canyon” is an example of a short story which has emotional closure without hermeneutical closure. Readers of lyrical short stories aren’t the kind of audience who feel short-changed if they don’t ever know who flew into the canyon after the tailgating incident.

NEW SITUATION

The main character doesn’t get what he wants. One deal closes (the wrong one), another deal fails to close (marriage).

Then there’s the tragedy of the unknown person who, for all we know, was trying to alert this couple to an axe murderer riding in the backseat of their car.

Tragedy has the reputation for breaking relationships. Friendships and casual romance can be broken by a shared negative experience. Louise breaks off her relationship with the narrator.

The narrator does not immediately accept that Louise is no longer interested in seeing him, for whatever reason. He continues to call her with updates on who the dead guy was.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

My refrigerator moment: Did the narrator really find all that stuff out about the mystery driver who flew into the canyon, or is he making it up? He’s clearly requiring a reason for calling Louise, though if he were a more emotionally mature person he could simply call her and tell her straight what he wants from their relationship rather than playing this game.

McGuane never tidies this story up for us. This is clearly deliberate. He’s intending for readers to see the main character’s romantic desperation, otherwise the narrator would have told us where he got the info from. If we go back to the beginning paragraphs, this is a guy who doesn’t sell his reader short on detail… where there’s detail to be told.

I extrapolated on second reading how ironically tragic it is that the main character didn’t achieve more maturity at the time he was seeing Louise, because he and Louise (at least how the narrator describes her) seem well matched. He kept insisting that they were a good match at the time, but he wasn’t any match for her yet. (He doth protest too much at the time about how good of a match he was.)

Does the older, wiser narrator really have a handle on Louise? I don’t think he’ll ever know why she wouldn’t have him. It’s easy to attribute it to the shared terror and tragedy of that trip, but it could just as easily have been the fact that he isn’t just closing the deal, as she suggests, both from a legal and moral stance. It could be because he scared the hell out of her by driving so fast to evade the tailgater.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Téa Obreht points out that landscapes of the American West lend themselves to serious mythic narratives rather than humour, perhaps, but another author who writes funny work about similar characters and similar situations is Annie Proulx.

Compare “Gallatin Canyon” with Annie Proulx’s short story “A Lonely Coast“, a story set on the other side of Custer Gallatin National Forest. Proulx utilises fire and lighthouse imagery. In this story too we have the ‘incandescent globes’ of the scary headlights. McGuane does in this story, Proulx ends her story with a drive along a highway ending in tragedy. Both short stories encourage readers to contemplate our own lack of freewill in a famously awe-inspiring landscape which is far bigger and more powerful than ourselves.

William Trevor’s “Bravado” is another short story discussed on the New Yorker fiction podcast. Trevor’s short story is also about a failure of masculinity, but this time starring even younger men. In both stories the viewpoint shifts to someone only peripherally connected. A young woman in “Bravado” wonders how much of a death (not caused by her) was ultimately her own fault. In both stories there is a peripheral death which will haunt the main characters for the rest of their lives.

Header image uses a screenshot from Google Earth.