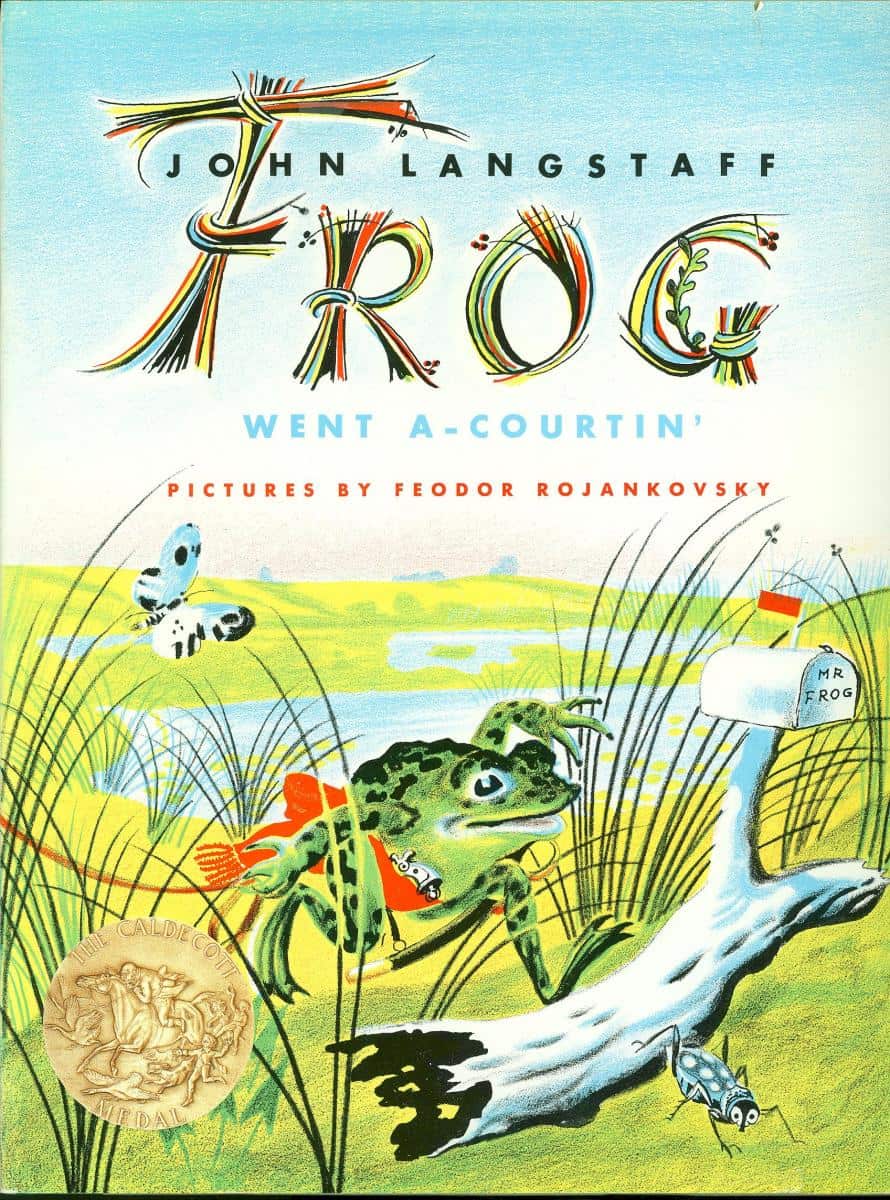

This month I wrote a post on Teaching Kids How To Structure A Story. Today I continue with a selection of mentor texts to help kids see how it works. Let’s look closely at Frog Went A-Courtin, a Scottish folk song from the 1500s, which was turned into an iconic picture book for children written by John Langstaff in 1955. There’s a brief history of the ballad included in the picture book which explains how the words of songs change and evolve over time. This case study is interesting because there is no true main character. This story is about a group of characters.

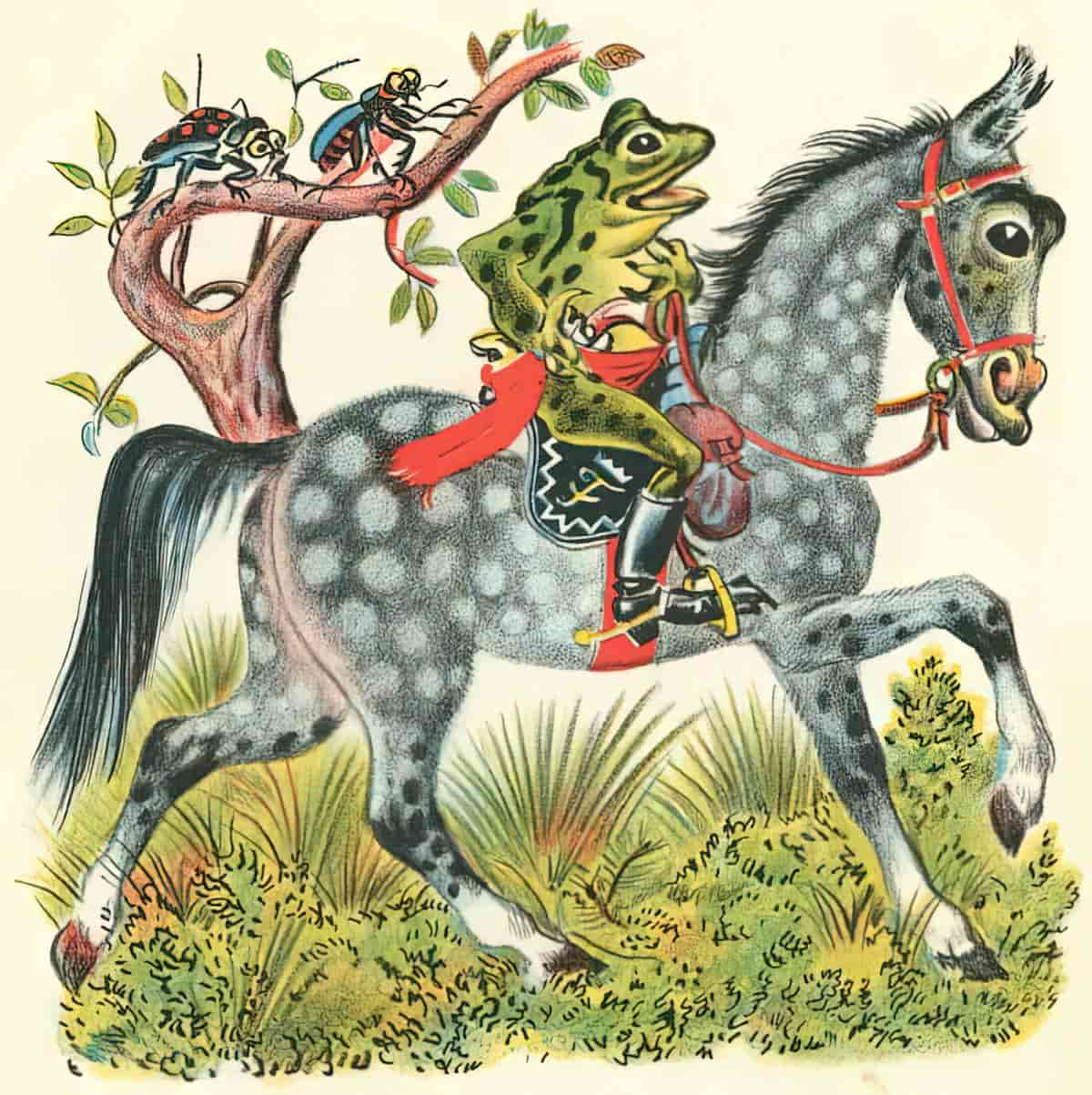

The illustrations are by Feodor Rojankovsky, who emigrated from Ukraine to America just as WW2 was cranking up. By that stage he’d already been a soldier in Ukraine and taken prisoner in Poland. If you’re familiar with Little Golden Books you’ll have seen his work elsewhere.

Frog Went A-Courtin won the 1956 Caldecott Medal.

First, a note on frogs in children’s stories.

Just so you know, in a picture book, frogs are the speedfreaks & grizzly bears are the stoners.

@lilymandarin

Frogs and Aesop

Unless you’ve got a really unusual animal like a naked mole rat, when animals appear in children’s stories, you pretty much need to go back to Aesop’s Fables and then you’ll see why these characters are the way they are. Frogs don’t feature heavily in Aesop’s tales, but there are a number of them. Unlike foxes, which are always cunning, or hens, which are always naive and vulnerable, frogs have no clear personality archetype. In Aesop’s fables featuring frogs all of the following can be said:

- Frogs have no natural ruler, unlike creatures of the jungle, who are ruled by the lion.

- Frogs are quite vulnerable because they are obliged to stay near water.

- Frogs can do silly things that lead to their own demise, but they are not natural tricksters.

- Frogs are capable of doing good deeds. They can also be stubborn, brave, timid and mendacious.

- Aesop used frogs when he wanted to set a story in or near a pond or in a well.

- Amphibian frogs exist in contrast to mice, who live on land and are about the same size.

On this last point, the Scottish folktale Frog Went A-Courtin is therefore a direct descendant of Aesop, setting mice up to contrast with frogs. Or perhaps humans naturally see frogs as the ‘inverse’ of mice, Aesop’s cultural influence aside. Humans think quite differently about animals when we don’t have a formal (or cultural) education.

Bear that in mind as we get to the ‘opponent’ part of the story.

STORY STRUCTURE OF FROG WENT A-COURTIN

Story in a nutshell: Frog courts a mouse. No one says that anymore. Frog woos a mouse? No one says that either.

Mouse must ask male relative for permission to wed frog, as she is considered chattel. That’s how women were treated in the 1500s and in many parts of the modern world.

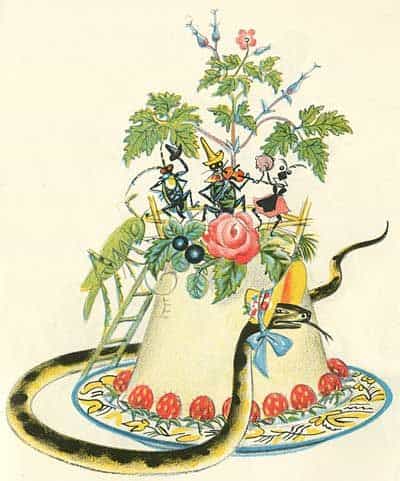

Mouse seems happy about it anyway. Mouse recounts her wedding plans to Uncle. Uncle Rat gives consent. The wedding itself doesn’t go exactly to plan, as a variety of creatures turn up. This creates a carnivalesque and cumulative story within the wrapper story of the courting. Finally the baddie turns up — the cat.

WHO IS THE MAIN CHARACTER?

Is Mr Frog the main character? The title suggests so. Mr Frog is a male bachelor amphibian whose life will not be complete until he has found a wife. So at first glance this looks like a romance, but in fact frog’s shortcoming (he needs to find a wife) only starts the story. He’s like a McGuffin character. (I’m not sure there’s such a thing as a McGuffin character, but we’ll go with it.)

In a true romance/love story, the finding of the bride/groom lasts the entire length of the story and the story stops at (or just before) the wedding. The MAIN part of Frog Went A-Courtin is the wedding itself, which makes this story a madcap farce. There is no true main character. This is an ensemble cast.

What is wrong with the ensemble? (What is their biggest shortcoming?)

I have to get something out of the way. I’m not sure if we’re meant to think this as we’re reading, though it’s inevitable to an adult, modern reader: This is a cross-species relationship. Also, how is a mouse related to a rat? They can’t breed with each other. Okay. Let’s ignore that for the sake of the story. We’re not supposed to consider these characters animals. They are humans in animal form, to lend the story a bit of madcap comedy. (Turning people into animals always lends a bit of madcap, though we’re so used to this now it’s no longer really funny in and of itself.) As for the frog in this particular frog story, he is heavily anthropomorphised. In other words, he’s basically a human. Man as frog simply gives a story a touch of madcap humour. This frog is the Every Man.

However! When we get to the big struggle scene (see below) we can no longer ignore the animal-ness of the animals, because that is integral to the plot. The cat would not be dangerous to those smaller creatures if it were not a cat.

To cut a long story short, in stories starring animals, sometimes the animals are people, sometimes the animals act as animals. Authors and illustrators use animals how they wish at any given time in order to suit the plot. That can happen. I do think it happened more in earlier eras of children’s literature. Olivia the Pig is always a little girl, for instance. She never goes rolling about in mud. Then again, Julia Donaldson’s Highway Rat is a contemporary story, and he is both humanlike (as a highway robber) and ratlike (as his punishment, cleaning crumbs from the bakery floor).

Here’s another point about animal characters: When animals act like human and are then required to act like their animal selves, that means everything’s gone to pot. Something’s gone wrong. Someone’s being punished. When humanlike animals behave like animals suddenly, this will only happen from the Big Battle onwards, not before. This is a different take of Masks in Storytelling. All along, the animals were only sort of pretending to be genteel like humans. Then something bad happens and their untamed, wild side emerges.

WHAT DOES THE CHARACTER ENSEMBLE WANT?

They want to have a fun time at the wedding party.

OPPONENT/MONSTER/BADDIE/ENEMY/FRENEMY

No one, until the cat turns up! A cat is the natural enemy because it is a much larger hunting animal.

WHAT’S THE PLAN?

There is a sequence where Miss Mouse tells her Uncle Rat how she would like the party to go. This makes it funny when the wedding party does not go like that. Planning a wedding is a bit like planning a birth — it’s impossible to plan everything to the last detail because events will take their course!

BIG STRUGGLE

Obviously this is the part where the cat turns up. With no words, the pictures show us the cat creates havoc. The small animals scatter.

WHAT DO THE CHARACTERS LEARN?

Frog Went A-Courtin is not a complete narrative because the ending is left up to the reader. Or rather, the reader is invited to participate in the story to create a full narrative of our own. I believe the ending is left off because it would not be interesting.

HOW WILL LIFE BE DIFFERENT FROM NOW ON?

Either that, or Miss Mouse got killed and eaten by the cat. Maybe that’s why the ending was left out. Jon Klassen did a similar thing in This Is Not My Hat. We surmise the little thieving scoundrel fish was eaten up by the big fish.

Let’s not dwell on this sad ending. Let’s say Mr Frog and Mrs Frog-Mouse lived happily ever after? And had beautiful frog-mice babies between them?

SEE ALSO

The Many Versions Of Frog Went A-Courtin from Mama Lisa