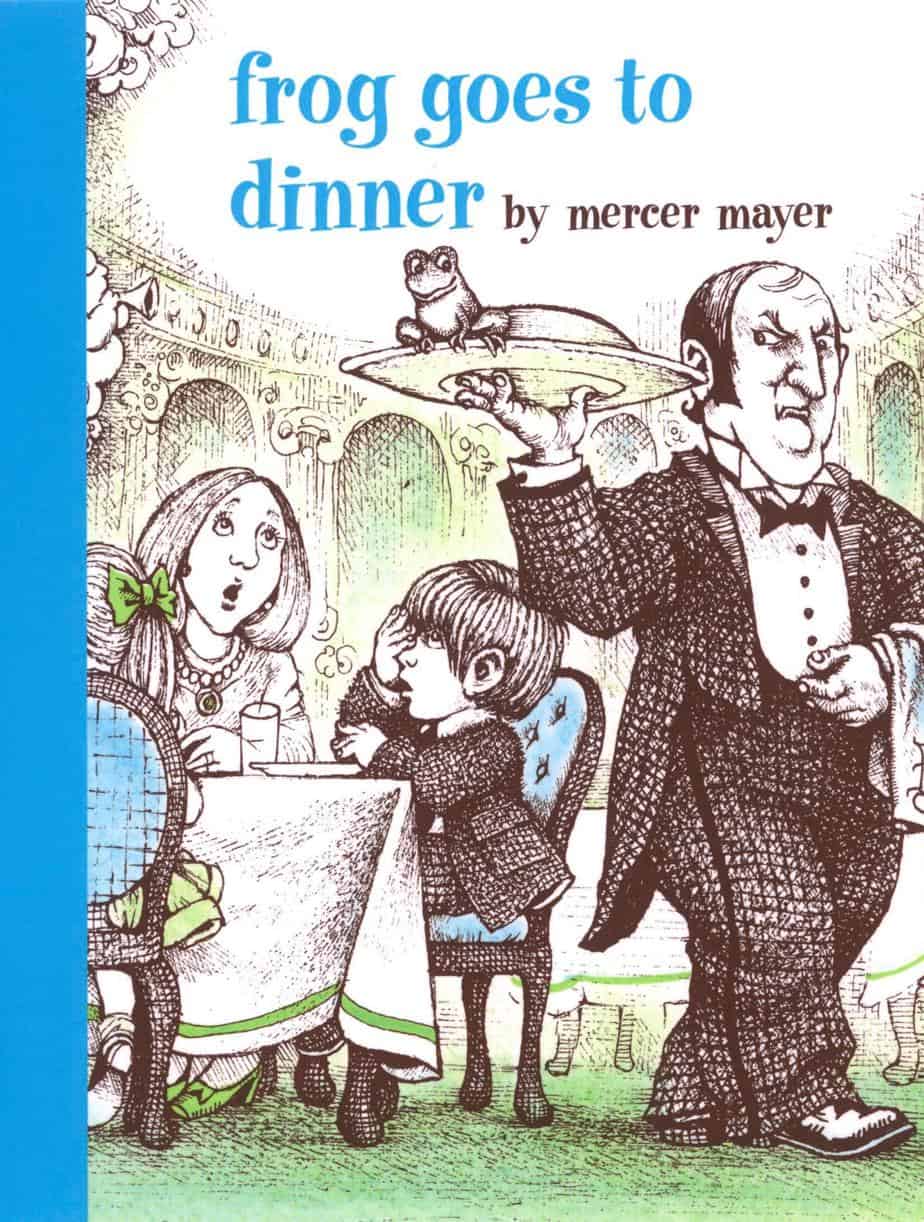

Frog Goes To Dinner (1974) is a wordless carnivalesque picture book by American author/illustrator Mercer Mayer, and the fifth in a series about a boy and his beloved frog. Wordless picture books are perhaps the most emotionally affecting, because they work with us at a deeper level. Frog Goes To Dinner works on an emotional level, especially compared to most carnivalesque plots.

Mercer Mayer has had a long career and his illustration varies slightly depending on what he’s doing and when he did it. I’ve noticed his earlier work is much more time intensive. The cross hatching of Frog Goes To Dinner is intense and varied. Compare this with his most recent Little Critter books, in which I get the feeling he’s a bit over it. I could be projecting but he has made so many Little Critter books! (Is it really 198? Unbelievable.)

Following the re-release of the first three books in this beloved series, here are the final three classic wordless tales in attractive, low-priced hardcover editions. A Boy, a Dog, and a Frog, the first book in this series, launched Mercer Mayer’s distinguished career over twenty-five years ago, and also helped to create the wordless picture book genre. Full of warm-hearted mischief and play, the books express the humorous trials and tribulations of friendship and the joy of summertime discovery. Readers will want to collect the entire set.

MARKETING COPY

CARNIVALESQUE STORY STRUCTURE OF FROG GOES TO DINNER

An Every Child is at Home

Alone in front of the mirror, a boy gets dressed up. Behind him stand three animals: a frog is closest, and behind are a dog and a tortoise. There’s a box with ‘My Box, Keep Out’ written on it. What’s in the box? (Nothing, right now.) The frog is clearly the boy’s favourite pet. There’s a picture of the frog pinned to the frame of his dressing mirror.

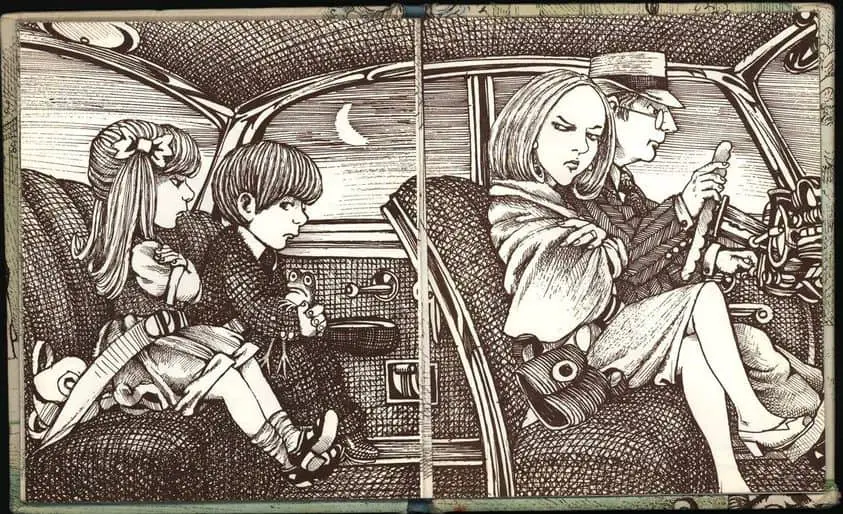

The boy and his family leave their home and go to a fancy restaurant for dinner. The sign on the restaurant literally says ‘Fancy Restaurant’. (I think that’d be a great name for a restaurant, though only if it wasn’t actually fancy.)

Dinner time is one of the most restrictive times of day for a child. The restrictions magnify when children go out to a restaurant. This raises the stakes.

In the West, at least, we expect children to sit still on chairs (which are too big for them). We expect them to follow strict table etiquette while dressed in clothes that they’re not allowed to get dirty, while eating messy, unfamiliar food with unfamiliar implements. They’re not supposed to move around or make a noise.

The dinner table is therefore ripe for anarchy, and other picture book creators have likewise overturned the rules of dinner, most notably Judith Kerr with her hugely successful The Tiger Who Came To Tea. (The English tea party is a formalised affair with strict rules of etiquette.)

The Every Child wishes to have fun.

There’s a bit more to this particular carnivalesque story than ‘wanting to have fun’. Sometimes children ‘face difficulties’ by having fun.

The boy is going somewhere unfamiliar. It seems to me that the frog has gone along as the boy’s emotional support animal. This is what gives Frog Goes To Dinner emotional depth. The boy seems a slightly anxious, emotionally in-tune child who can only relax fully when he’s safe and sound back in his own bedroom, as we will see at the end.

The child stars of carnivalesque picture books are often this type of kid.

The child stand-in, however, has other ideas. (The frog.) We might say that the Ally In Fun is the fun flipside of all children — a side only rarely permitted to come out.

Disappearance or backgrounding of the home authority figure

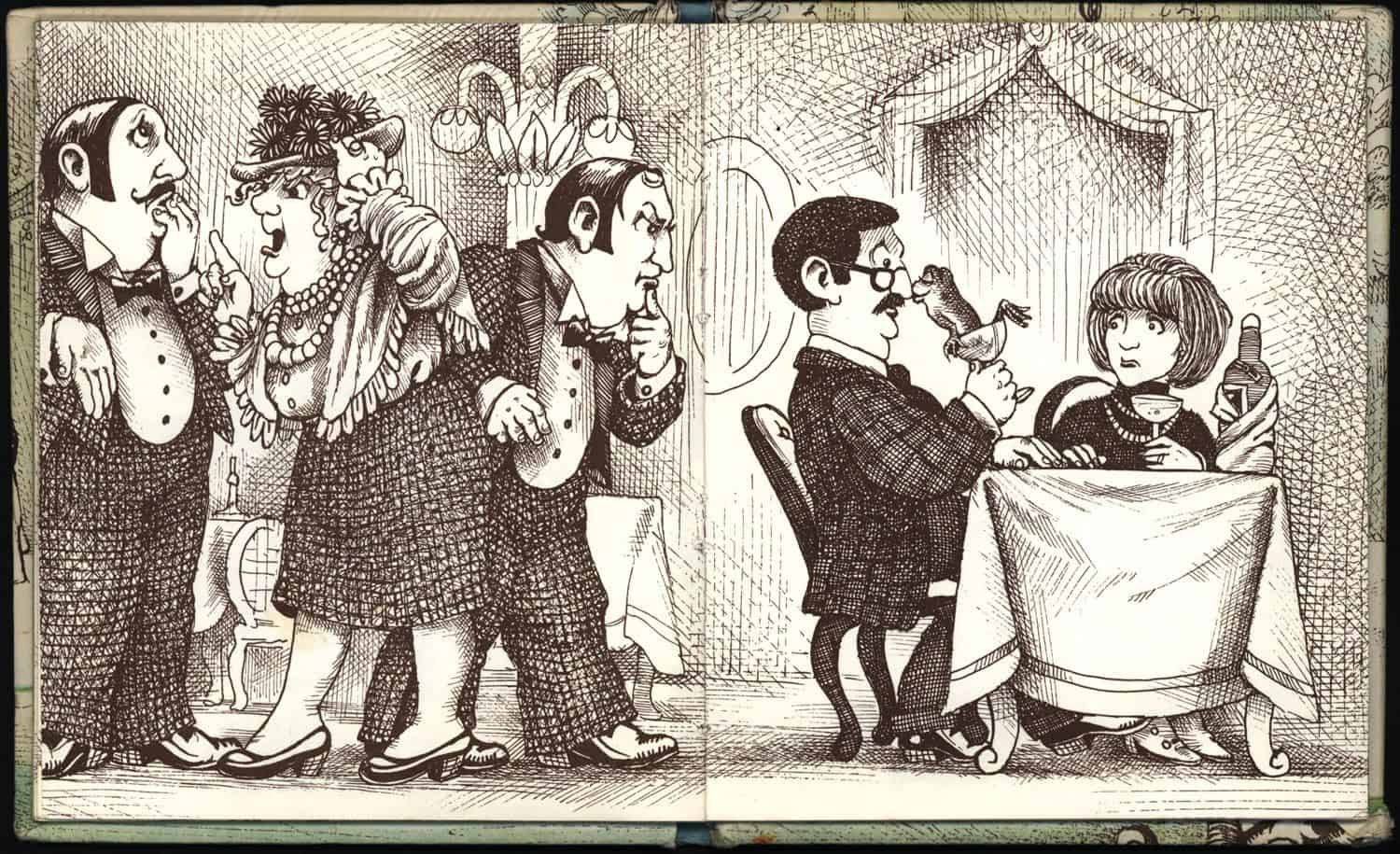

The family are all sitting at the same table together, but the ‘camera’ doesn’t follow them — instead we follow the frog as it hops from one situation to the next. In this way, Mayer ‘disappears’ the caring adults.

My refrigerator moment: Wondering why the parents didn’t step in earlier! (Answer: Because that would have ended the carnivalesque adventure prematurely.)

Appearance of an Ally in Fun

The emergence of the frog out of the boy’s pocket. The boy hasn’t actually taken his frog with him deliberately. Mayer sets this up earlier by showing the frog jumping into the boy’s coat while the boy is busy petting his dog goodbye.

Hierarchy is overturned. Fun ensues.

Oh, boys and their frogs, am I right!? There’s a long storytelling history of boys who love frogs, or rather, grossing everyone else out with frogs. The boy with a frog in his pocket is Peak Boy — loveable and harmless.

Another standout example of the mischievous boy with the frog is Fern Arable’s brother, Avery. Avery’s interest in frogs suggests he’s not quiet enough to sit still in a barn for the time it takes to really become in-tune with the animals (who can talk, if only you listen hard enough). The frog-carrying boy is a particular kind of boy.

Honestly, I find this trope a little irritating. The boys with their frogs are fine, but they invariably take delight out of disgusting a prettily-dressed girl, which plays into that whole Female Maturity Formula issue I’ve written much about. When this same gender dynamic plays out time and time again across the corpus of children’s literature, the message is clear: Boys are fun and adventurous; girls are prissy and boring. Throughout this story, the female characters are more disgusted and affected by this frog than the male characters. The woman on a date almost faints when the frog kisses her date’s nose, and needs him to escort her out.

There’s a long fairytale history in which female characters are disgusted by frogs. See The Frog Princess.

This gender binary ideology transmits despite the Avery Arables of children’s book world, juxtaposed against quieter, more observant Ferns, which at first glance may seem to offer ‘balance’ (as in, boys and girls are different but each have their own unique strengths). My issue is this: The difference between individuals is far greater than differences between genders, but you wouldn’t get that message from reading 20th century literature.

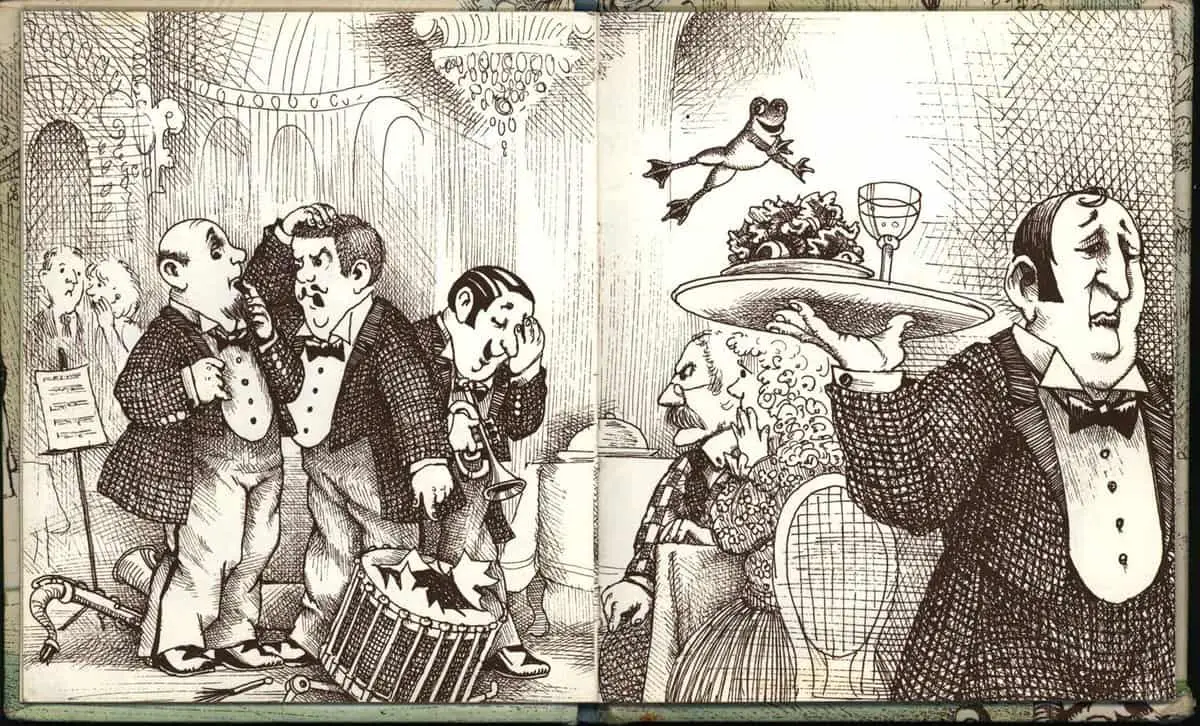

So, the frog pops out of the boy’s pocket and upsets the live band by climbing into a wind instrument.

The reader can see in advance what’s going to happen, especially after the musician peers right into his instrument. Of course the frog will end up plastered to his face! This is the old kink in the hose/hose in the face gag.

Fun builds!

When child characters break the rules of society, it’s not quite as fun if no one in power is around to disapprove. There’s no disapproving audience in the stand-out carnivalesque story, Dr. Seuss’s Cat In The Hat, but there’s always the threat of the mother’s return home at any minute, and we can just imagine her disapproval.

While the fancy lady gives a serve to that hapless waiter, she fails to notice the real maker-of-mischief — the frog, who appears in another man’s martini glass. Hopelessly unobservant characters are a failsafe gag, especially in children’s stories. The child notices what the adults do not. This, too, is a common feature of children’s literature, whether comedy genre or otherwise.

Peak Fun!

Finally, a waiter takes the frog by its feet and throws it out the door. Just as well this isn’t a French restaurant.

At this moment, the boy sees what’s happened: That’s HIS frog! The mother angrily shushes him.

The boy is heroic when he ignores his mother’s instruction to be quiet and tells the waiter that the frog belongs to him. The waiter’s angry face and pointing finger shows that the whole family must leave, “And take your frog with you!” They leave through the fire exit, in stark contrast to the way they came in, with the fancy footman in the highly decorated jacket. (The undignified ending justifies that scene.) As in Where The Wild Things Are, the family has gone without dinner for punishment, though I assume they’ll have beans on toast or a sandwich once they get home.

Not the boy, though. The boy his sent to his room. The sister pokes out her tongue at him, though I do wish she could have enjoyed the mischief along with the same-aged girl readers. Instead she is portrayed as a miniature mother. (A key aspect of the Maturity Formula.)

Surprise! (for the reader)

Contemporary carnivaleque picture books tend to have strong gags or reversals to finish them off cf. Stuck by Oliver Jeffers.

But the ‘surprise’ doesn’t have to be a gag. This is a more emotionally intune picture book and I believe the ‘surprise’ comes from seeing the boy act heroically by fessing up to a scary authority figure as the owner of the frog.

Return to the Home state

The illustration below shows the boy’s entire family disapproves. Though the boy doesn’t show much emotion, the frog offers an insight into what he must be thinking.

The boy isn’t fully ‘home’ until he is ‘alone’ in his own bedroom, along with his frog, and other two pets.

Across Mercer Mayer’s work we can see the subplots of two animals doing their own thing as humans go about their lives — notably, the grasshopper and spider in the Little Critter series. (Cf. Just Me And My Puppy.)

Boy and frog roll around on the floor laughing, freshly relaxed. The dog and tortoise remain perplexed. They don’t know what just went down. But the reader does, and we feel delightfully complicit.