My reading of “Free Radicals” by Alice Munro (2008) is highly metaphorical. To me, this is a story about the Kubler-Ross stages of grief, and the new vulnerability older women feel when their male partner dies before them.

Read literally, though, and this is the story of one woman’s brush with a serial murdering intruder — a rare crime story from Alice Munro.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “FREE RADICALS”

The structure of this short story is exquisite: a metadiegetic narrative within a dream sequence within a framing story.

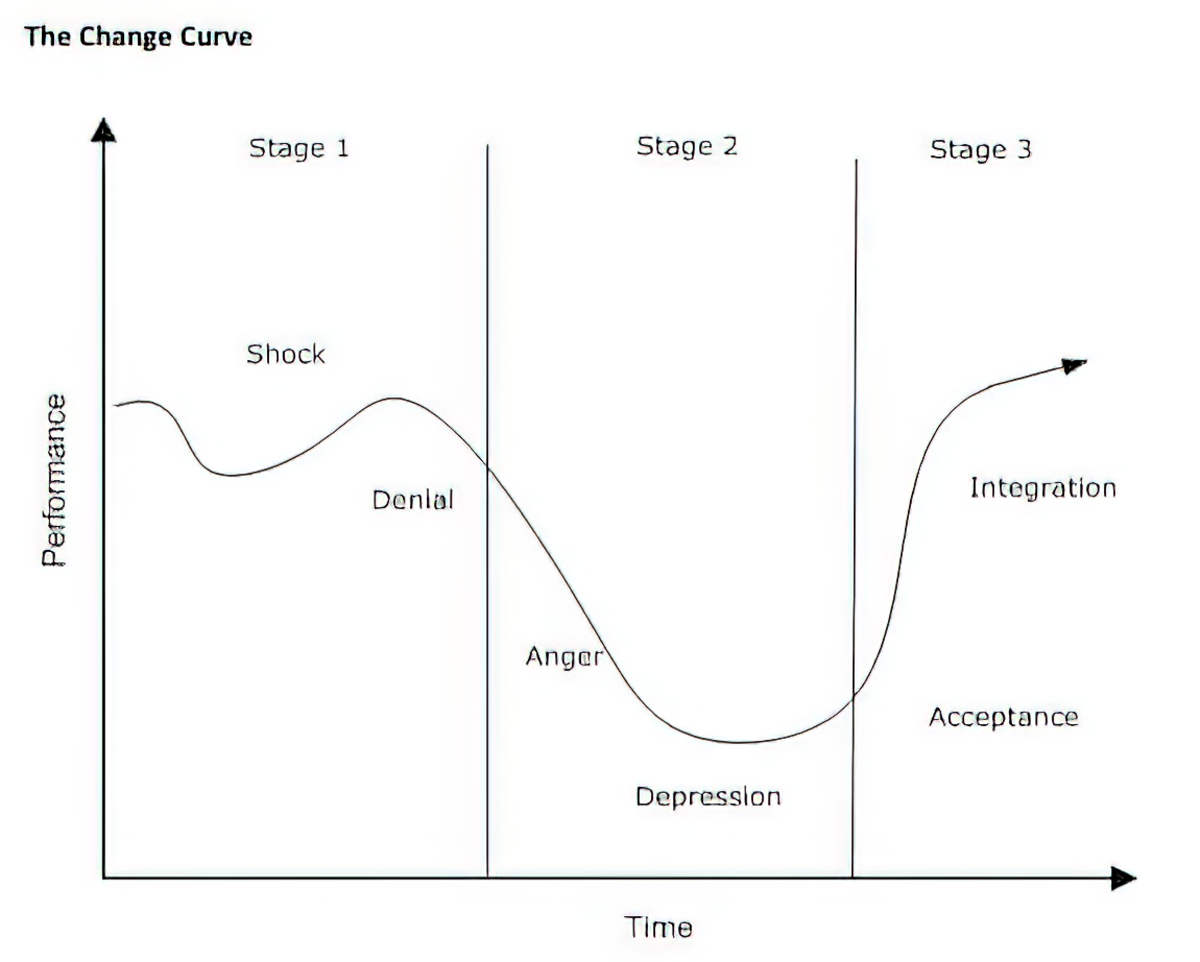

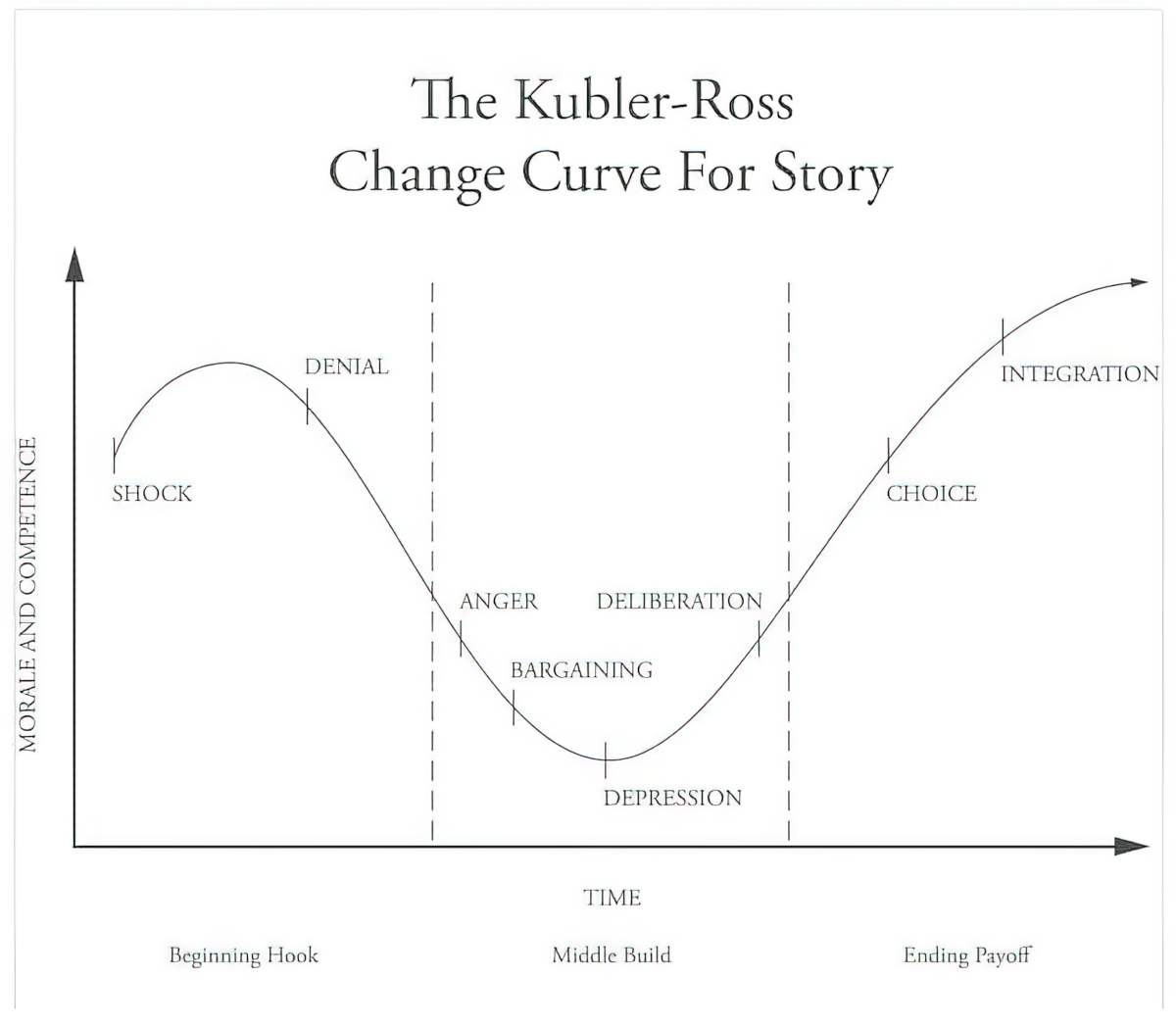

Before diving deep into “Free Radicals”, refer to the Kubler-Ross Change Curve, especially as adapted for Story. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross is famous for her research into grieving and end-of-life psychology. Her stages of grief have since been mapped onto a narrative arc. (This psychology applies to anything major and shocking in our lives.)

There are various versions of this chart because psychology has changed over the decades. Here’s another one adapted for the Shawn Coyne way of looking at story:

Alice Munro lost a baby daughter soon after giving birth in her early twenties. By the time Munro published “Free Radicals” in February 2008, she was no stranger to ageing, ill-health and grief.

The interaction in the kitchen between Nita and the intruder forms a mini-grief story in its own right. Refering to the chart: At first Nita is Shocked by the man as he stands in the doorway. She is shocked again when he demands something to eat, but she plays along with the situation, trying to tell herself — and him — that she’s not scared. Denial.

There’s a metadiegetic narrative nested one level deeper in the kitchen scene, when Munro transfers the Anger stage of Nita’s grief onto the (imaginary) intruder, who has just murdered his own family.

Why did he murder his family? Because he couldn’t face the care responsibilities imposed upon him without warning. It wasn’t what he was expecting as ‘part of life’s deal’. So he abdicated his responsibility entirely, as Nita perhaps feels her own husband did to her.

Nita feels residual guilt about what happened with her husband’s first wife. Thus, due to the ghost set up in the first section of the story, Nita imagines herself as this man. It is easy for her to imagine she is just like him. She tells him they are as bad as each other.

She also imagines this man as her husband who, likewise, took off without hanging around to fulfil his obligations of care (to Nita, rather than to the disabled sister).

See how Alice Munro masterfully achieves both proxy amalgamations at once?

This is how Nita works through her grief — imaginatively. This melodramatic kitchen incident is our explanation for why she is so scared to go down to the cellar — terrible things come up from there.

In the symbolic dream house, the cellar is a place where dark things happen. As the dream house predicts, bad things come up the stairs from the cellar. The cellar is the housing equivalent of the fairytale forest — it is the subconscious. It’s all very Freudian. But Gaston Bachelard is the go-to guy for reading all about that.

SHORTCOMING

Nita is grieving and that is her main psychological shortcoming. It is kept as a reveal that she herself is dealing with cancer and will be dead within the year. Her much older husband, who just received a clean bill of health at the doctor’s, has died suddenly. She is therefore in shock. She feels betrayed.

Off the page but important: Nita’s husband is not going to be around to take care of her now. Nita will face the worst of her illness completely alone. Unlike her husband’s swift death, her demise is a slow one. Unlike Rich, Nita needs to find a way to cope with all that fear.

We are offered a few clues about Nita’s vulnerable psychological state. I’ve written separately about my theory that she’s a candidate for hoarding disorder. But this is not a story about that. And really, the hoarding disorder interpretation is a bit of a stretch on my part because it tends to come on a year and a half after a sudden and expected loss, not immediately. I still find it fascinating and, in some counter-intuitive way, an intruder coming to take Nita’s husband’s car might actually be an easier way to get rid of the darn thing rather than her having to sell it herself, thereby offering up for sacrifice yet another remnant of him.

Nita is immensely vulnerable now. She can’t drive, for example. She no longer has a driver in her husband. Worse, there are places in her own house where she won’t even go. Nowhere is safe. Life itself is not safe.

She doesn’t even consider this her own house anymore. She came by it in a slightly underhanded way, she feels. We learn this via backstory — she was the other woman who broke up her husband’s first marriage. Especially in earlier eras, ‘the other woman’ was always blamed in such situations.

Munro reminds us of that, but doesn’t parse the unfairness of it. That’s up to us. Munro simply tells the reader that Nita lost her office job because of it. Rich kept his job, but — perhaps only in his head — he feels he missed out on a promotional opportunity that was owed to him. (This is how we know he’s a white man — his sense of entitlement.) Important to remember: It wasn’t young Nita who cheated. It was the husband, who betrayed the trust of his first wife.

This relationship history (her moral shortcoming) is Nita’s ghost — an event from the distant past affects her psychology in the present. Munro weaves this backstory concisely throughout the story of the present. (Is there such a word as frontstory?)

DESIRE

In a bereft state does anyone truly desire anything, other than to reverse time and get their loved one back? Since no one can do anything about that, this deep desire doesn’t make for a satisfying story.

As for the surface level desire, living from day to day, Nita would like to clean up the house. She knows she needs to deal with the logistics of losing her husband. She needs to sell his car, for instance.

Clearing out his stuff means she has to go into parts of the house that scare her, which neatly joins ‘desire’ to ‘shortcoming’. (All of the best stories do this.)

This is what she wants to do in this particular story, or rather in the second portion, when she’s starting to come out of her Shock.

OPPONENT

Nita’s husband has let her down. He was supposed to stick around and take care of her. Rich is her opponent.

But rather than be angry at Rich, who is dead, and who didn’t die to spite her, Nita invents a proxy upon which to paste the Anger stage of her grief.

Perhaps within the real world of the story a man does come to check the meter and then leaves. I think Nita makes up the story about the serial killer intruder. She either imagines this scenario while the man is down in her cellar, or she imagines it later, after the police officer tells her that her husband’s car has been stolen. Perhaps the police officer and the stolen car is imagined as well. But since it’s not melodramatic, I decode that section as real.

The main clue: Nita feels vulnerable in her own home, ‘unable to sit down until he’s gone’. When this meter reader arrives and apologises for startling her, insisting on removing his shoes, this is completely at odds with the man he reveals himself to be. That’s not to deny that trickster criminals exist, of course. Besides that, I find this story implausible on a literal level. And a crime story about an encounter with a psychopathic murderer doesn’t fit well into Munro’s oeuvre. An imaginary encounter fits much better.

In fact, I believe Nita is a fairytale trickster and the intruder is a fairytale fool. Poison itself is very fairytale, harking back to stories of witchcraft. Hence, I propose the incident is imagined.

In case we missed that Nita has invented this story for the (imaginary) intruder, she makes sure to tell us, which is an interesting choice. Some critics have said that if she hadn’t told us, we’d never have known.

But the very idea that it would be easy to kill someone with rhubarb leaves is a bit of a stretch in itself. Sure, they are poisonous, but you’d have to eat a LOT of it. So much that you’d definitely know you were having it:

The chemical villain in rhubarb leaves is oxalic acid, a compound also found in Swiss chard, spinach, beets, peanuts, chocolate, and tea. Chard and spinach, in fact, contain even more oxalic acid than rhubarb—respectively, 700 and 600 mg/100 g, as opposed to rhubarb’s restrained 500. Rhubarb’s killer reputation apparently dates to World War I, when rhubarb leaves were recommended on the home front as an alternative food. At least one death was reported in the literature, an event that rhubarb has yet to live down.

Oxalic acid does its dirty work by binding to calcium ions and yanking them out of circulation. In the worst-case scenario, it removes enough essential calcium from the blood to be lethal; in lesser amounts, it forms insoluble calcium oxalate, which can end up in the kidneys as kidney stones. In general, however, rhubarb leaves don’t pose much of a threat. Since a lethal dose of oxalic acid is somewhere between 15 and 30 grams, you’d have to eat several pounds of rhubarb leaves at a sitting to reach a toxic oxalic acid level, which is a lot more rhubarb leaves than most people care to consume.

National Geographic

(Did the guy who died on the war front really die from rhubarb leaves? Or was it perhaps something else entirely…?)

PLAN

Imaginatively, Nita’s plan is to convince the murderer that she is also a murderer. If they each keep the other’s confidence, he may choose to let her live for a while longer.

BIG STRUGGLE

As I’ve already proposed, the kitchen is the Battle scene, but it’s a proxy for the psychology of grief.

(The real Opponent is Nita’s dead husband, who isn’t there and so cannot take the blame.)

ANAGNORISIS

Nita realises how very much she misses her husband. This probably marks the moment where Nita moves past Anger into something darker but more real (Depression).

I found myself lingering on the following sentence, absorbing the weight of it:

Rich. Rich. Now she knew what it was to miss him. Like having the air sucked out of the sky.

NEW SITUATION

Unless we interpret the intruder as a dream sequence, how to explain why Nita wouldn’t tell the police about him?

The policeman (who I interpret as real within the story) gives Nita a ‘stern lecture’ about leaving keys in a car. He puts the wind up her, when she really doesn’t need that. He has underestimated how vulnerable she already feels. The story ends with “You never know”, repeated.

Then again, perhaps Nita finds it comforting on some level to imagine the worst almost happened to her in her own kitchen, yet didn’t.

Imagining worst case scenarios is one common way of coping with fear. I notice it especially when women are advised to buy weaponry for self-protection. People are quick to suggest this, thinking a gun in the handbag can save you. The statistics don’t hold up. Your own gun is far more likely to get you killed than to kill your assailant. Yet we like to imagine that if we only concoct a strong enough plan, then that plan will protect us, if worst comes to worst.

If only. If only. Stories about the ‘if only’ are emotionally resonant.

Likewise, Nita has a plan for living in her house as a single, ailing old woman. If this meter reader who startled her at the door does turn out to be a psychopathic murderer on the run, she’ll tell him she is, too. She’ll draw on a past event and tell him as catharsis. They’ll build empathy, she’ll give him the car (because she needs to get rid of it anyhow) and he’ll leave her be.

That’ll definitely work.

We know our worst-case-scenario imaginings won’t work, yet we imagine them anyway.

OTHER WRITING TECHNIQUES IN “FREE RADICALS”

the narrative pause

Apart from the story nested inside a dream, there’s an especially noteworthy technique Munro uses in this story. She speeds us up then applies the brakes.

A little while ago I started looking more carefully at how stories are paced. I’d read Jane Alison’s Meander, Spiral, Explode.

According to that continuum, the slowest pace a narrative can achieve is the Pause. In a film, that’d be a freeze frame. But how is the ‘freeze frame’ achieved in the case of the written word?

Alice Munro uses two separate techniques for achieving the Pause in “Free Radicals”.

- She describes what is Not rather than what Is. Nita walks into the rooms of her house and all she notices is that her husband is not there.

- The intruder has a photographs. Well, two photographs actually — the second is gruesome and produced as a jump scare. When the narrator describes that photo, the narration is now on a different kind of Pause. (This is a technique known as ekphrasis — writing about art used to be very popular and a subgenre in its own right. Before artworks and photographs were commonplace, that is.)

These deliberate pauses slow the story right down to a standstill, yet at other parts of the story we get summary. This is Munro speeding the story up then slamming on the brakes. Psychologically, Munro is replicating the feeling of grief. At times there’s the never-ending weight of it, the feeling it will never leave you. Then there’s the looking back in time, realising how fast life seems to have passed you by.

TRAIN MOTIF AS FATE

Which brings me to trains. Alice Munro is a big fan of trains. A writer can eke a lot of symbolism out of trains, for sure.

What about the train thread in this story? First, the sexe en plein air near the tracks, between Nita and Rich. Later, the train reappears and now it is a symbol of fate.

“You wait till I say. I walked the railway track. Never seen a train. I walked all the way to here and never seen a train.”

“There’s hardly ever a train.”

The train track itself led the murderer to Nita’s house. There was nothing she could do to stop him. This fate was set in place the moment she started the affair with Rich. (And even that was probably fate.)

It is comforting, sometimes, to think that certain events set our lives in motion and that there was nothing we could possibly have done to change them. I watched an episode of Insight (with Jennie Brockie) once in which mothers talked about losing their young children. One woman stood out as different from the others. She appeared to be dealing much better than they were with the loss of her daughter, who was pushed off some train tracks into the path of an oncoming train. She reasoned it like this: The child was only given so much time on earth. And when her time was up, it was up.

I wish I could believe that. I think that view would be helpful, more than the view that our choices determine everything, in which case our decisions could imaginatively extend our own lives, or the lives of our loved ones. If only we had lived life differently.

THE TITLE

Its title suggests an additional version of the operations of possibility-space and its constitution. These radicals are highly reactive, which makes them likely to take part in chemical reactions, but only in so far as they do it according to their own pre-coded set of possibilities. Being an atom with unpaired electrons, the radicals seek balance by stealing an electron from another atom that then becomes a free radical. A chain reaction is caused. As the metaphor for a story that features a woman visited by a dangerous murderer, there seems to be a chain reaction caused by a miserable childhood. However, it is suggested in the story that bad or good are not features so easily dug out, and as the metaphor suggests chemical reactions can be both bad and good.

Ulrica Skagert

The health significance of this title will probably get lost over time, but I definitely remember a time when health media was all about avoiding free radicals. Certain wonder foods would get rid of them. Nobody but scientists actually knew what they even were, except we knew they were very bad.

Then there was an about face, as with all dietary messages. Now we were told that a certain number of free radicals are essential for human health. (The same applies to cholesterol, viruses and a bunch of other ‘bad’ things.)

Free radicals have long been associated with tissue damage. A new study shows that they also promote regeneration.

an article from 2018

Antioxidants may encourage the spread of lung cancer rather than prevent it

Science news from 2019

As part of all this scaremongering, the public were told that free radicals cause cancer. Hence the cancer link in this story. But there’s also the feeling of betrayal at work here, I think. Nita was betrayed by by the message that red wine is good. She still got cancer. (This explains the constant reference to drinking, too.)

In the early 2000s, Alice Munro herself underwent major heart surgery. She came through it well, but has said in interview that she couldn’t understand why a major artery was fully blocked. She’d done exactly as she thought she was supposed to — she ate well and exercised daily. Her doctor told her she was simply old. She had to face up to the fact of ageing. I hesitate before mapping an author’s life too closely onto a the life of their fictional inventions, because it’s never a one-to-one correspondence. But I feel that experience of heart surgery must have partly inspired this story.

We are all betrayed eventually, even if we manage to avoid health news parsed by the media. Old age is one long betrayal. We are betrayed by loved ones dying around us. We are betrayed by our own bodies. Long before that, we are betrayed by this message that if only we are sufficiently well-behaved, if only we can control ourselves, then we can dodge death.

See how this all links up to the kitchen scene? Nita dodged death. But only for now.

WHAT TO SAY TO THE RECENTLY BEREAVED

- I’m Sorry You’re Suffering, from Persephone.

- When It’s Not God’s Plan: 8 Things to Say to Grieving Nonbelievers from AlterNet

- What To Say and Do For The Recently Bereaved at Medium, who recommends this book:

- Joan Didion’s essay on grief

MAYBE NOT

A dead creature is in every respect identical to a live one, except that the electrochemical processes that motivate it have ceased.

from Here on Earth (by Tim Flannery)

OTHER STORIES IN MUNRO’S TOO MUCH HAPPINESS COLLECTION

- “Dimensions” —

- “Fiction” —

- “Wenlock Edge” —

- “Deep Holes” —

- “Free Radicals” —

- “Face” —

- “Some Women” —

- “Child’s Play” —

- “Wood” also in the November 24, 1980 edition of The New Yorker

- “Too Much Happiness” —