Food plays an important role in children’s literature, and is one difference between mainstream literature and literature for children. Food means all sorts of things throughout literature — sometimes it symbolizes good, other times evil.

Writers don’t care what they eat. They just care what you think of them.

Sport, Harriet the Spy

Why All The Food in Children’s Literature?

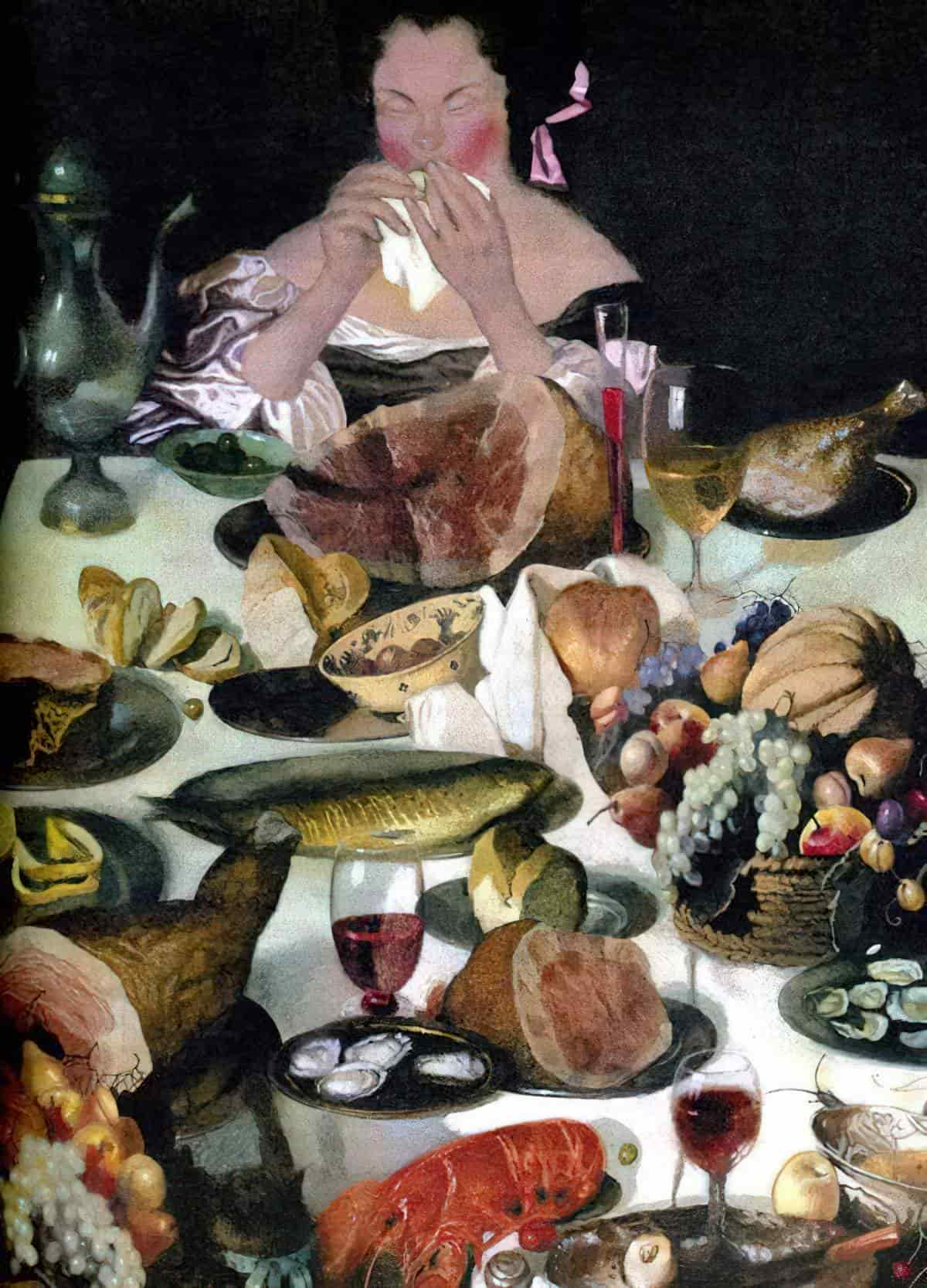

The feasting fantasy in children’s literature is a particularly good vehicle for carrying culture’s socializing messages: it acts to seduce readers; through mimesis it “naturalizes” the lesson being taught; and, through the visceral pleasures (sometimes even jouissance) it produces, it “sweetens” the discourse and encourages unreflexive acceptance of the moral thus delivered. Hence, while ostensibly pandering to hedonism, a feasting fantasy frequently acts didactically.

Voracious Children: Who eats who in children’s literature? by Carolyn Daniel

Several scholars have pointed out the parallel between sexuality in general fiction and food in fiction for children. Glutton and greed are common motifs in traditional children’s literature, inevitably followed by punishment.

Maria Nikolajeva in The Rhetoric of Character in Children’s Literature

Without food everything is less than nothing.

Bunyip Bluegum

Here are a few things to bear in mind when you come across food in literature:

- All food in literature is symbolic, since made up people don’t actually need to eat anything.

- In Western philosophical thought (e.g. Freud), everything inside/edible is aligned with the self and is good. Everything outside/inedible is aligned with the other and is bad.

- Inside/self = mind/reason, outside/inedible = body/passion. This also leads to a whole nother discussion about phalluses that I’d rather erase from the history of Western thought, thanks. (It pits the masculine against the feminine in a way that supports an unhelpful gender binary. Also, femininity = thinness = mind over matter.)

- The ultimate ‘bad eater’ is the cannibal = the antithesis of humanity.

- Food is obviously culturally specific. Bear in mind that in the West, our list of acceptable proteins is quite narrow. A lot of this comes from the food rules as described in Leviticus. (Sheep, pigs, cattle, chickens = OK. Pretty much everything else = NOT OK.) In Jewish culture, no pigs either. Hindus, no beef.

- Some animals are accorded a sort of interim status similar to humans. In kidlit, dogs.

- Food fantasies were especially prevalent in England during the Victorian era (due to underfeeding of children) and during the world wars (due to rationing).

- Relatively expensive ice cream and chocolate products tend to be marketed at adult women whereas cheap sugary products are marketed at children, but in literature, children get to eat the expensive ones.

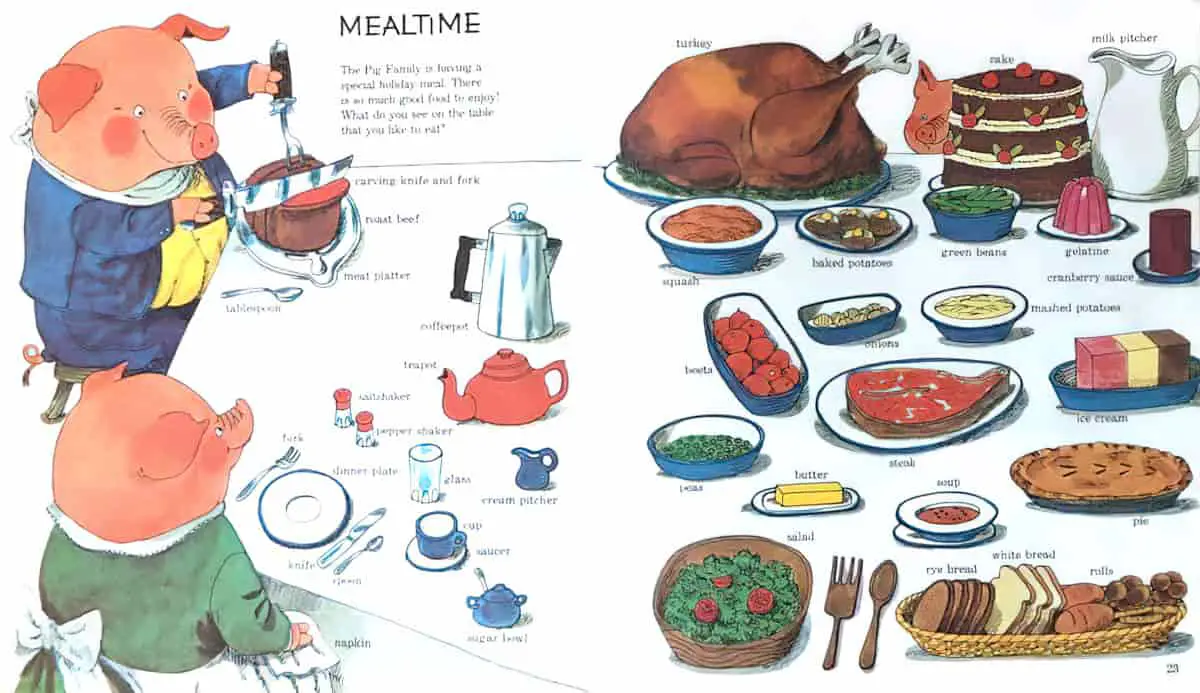

Some classic and well-known children’s books are famous for their celebration and proliferation of food and mealtimes:

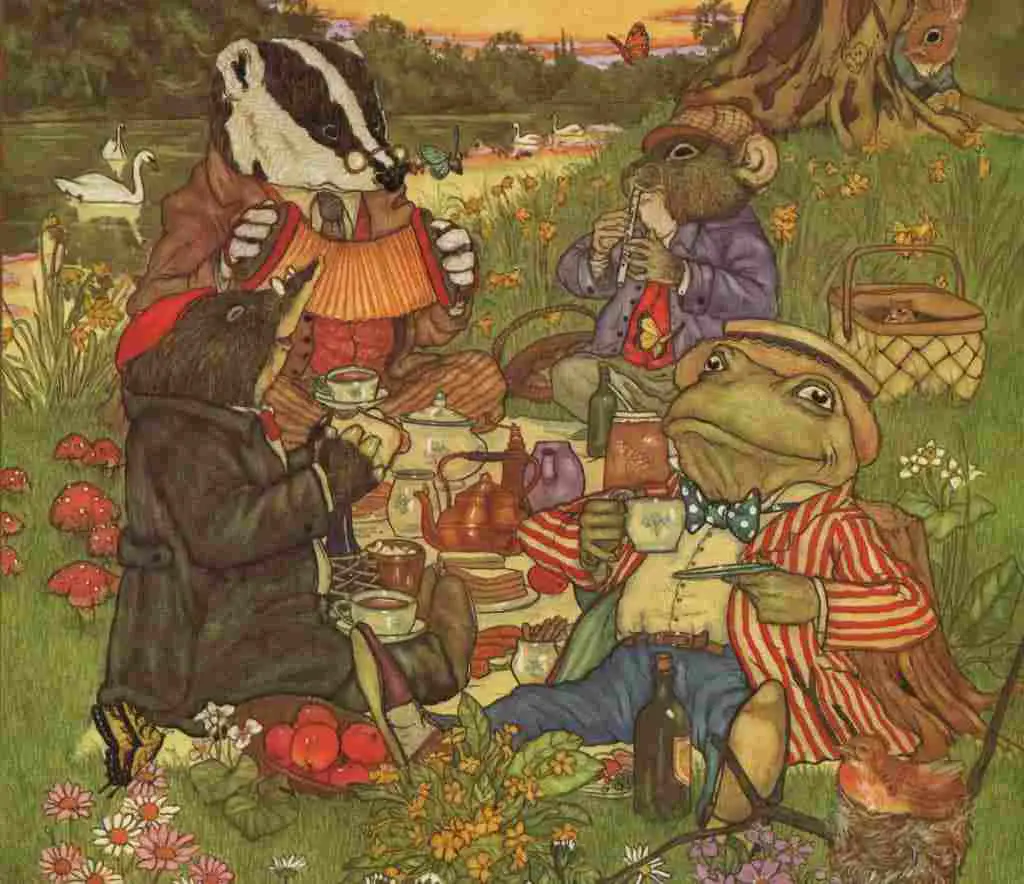

The Wind In The Willows

Many stories of Enid Blyton, such as the Famous Five Adventures and the Faraway Tree trilogy

“Soon they were all sitting on the rocky ledge, which was still warm, watching the sun go down into the lake. It was the most beautiful evening, with the lake as blue as a cornflower and the sky flecked with rosy clouds. They held their hard-boiled eggs in one hand and a piece of bread and butter in the other, munching happily. There was a dish of salt for everyone to dip their eggs into.

‘I don’t know why, but the meals we have on picnics always taste so much nicer than the ones we have indoors,’ said George.”

Enid Blyton, Five Go Off in a Caravan

The symbolic meaning of food which we see in Arcadia children’s books is present in travel instructions too. It has been noted that in no other children’s books do the characters eat as much and with such relish as in Enid Blyton’s adventure novels. In adult formula fiction, this corresponds to excessive drinking and sexual exploits. The reader partakes in behaviour which is not wholly accepted in our society, an initiation into the “other” and the forbidden.

Maria Nikolajeva, From Mythic to Linear: Time in children’s literature

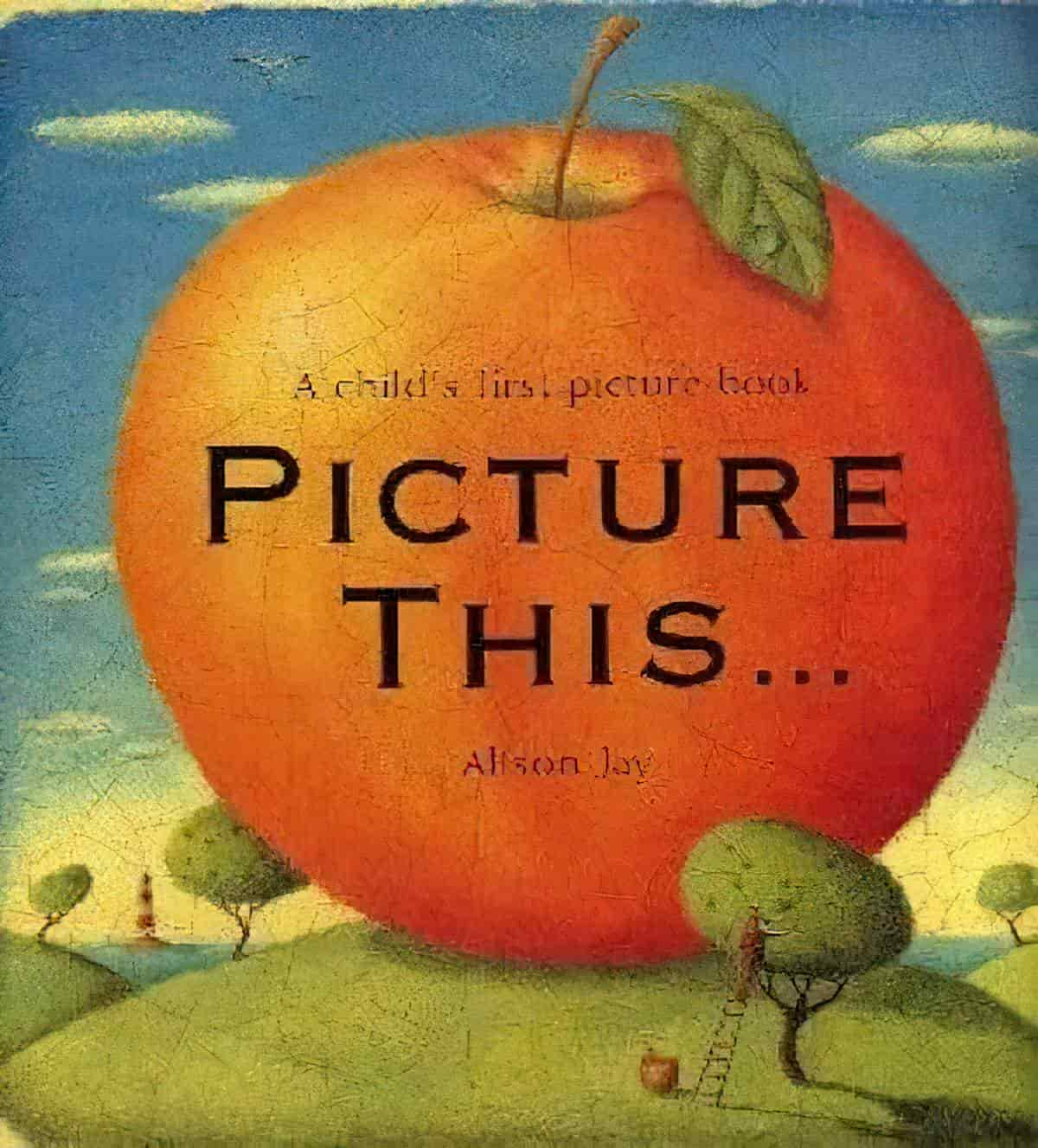

If you’ve ever read something about how to improve your memory for lists of objects, you may be familiar with the advice to play with size. For instance, if you’re heading to the shops and you need to buy apples, imagine a massive apple on top of the hill behind your house.

Simple in format, with vibrant folk-art inspired paintings of everyday items and a single, large-type word on each page, Picture This . . . is the ideal first word book for the very young. But there is much more to Picture This . . . than first meets the eye! Each turn of the page reveals a new perspective on what has come before and gives a hint of what’s to come. Parents will delight in reading this book with their children, finding visual surprises together and following the gentle story as it progresses through the day and through the seasons.

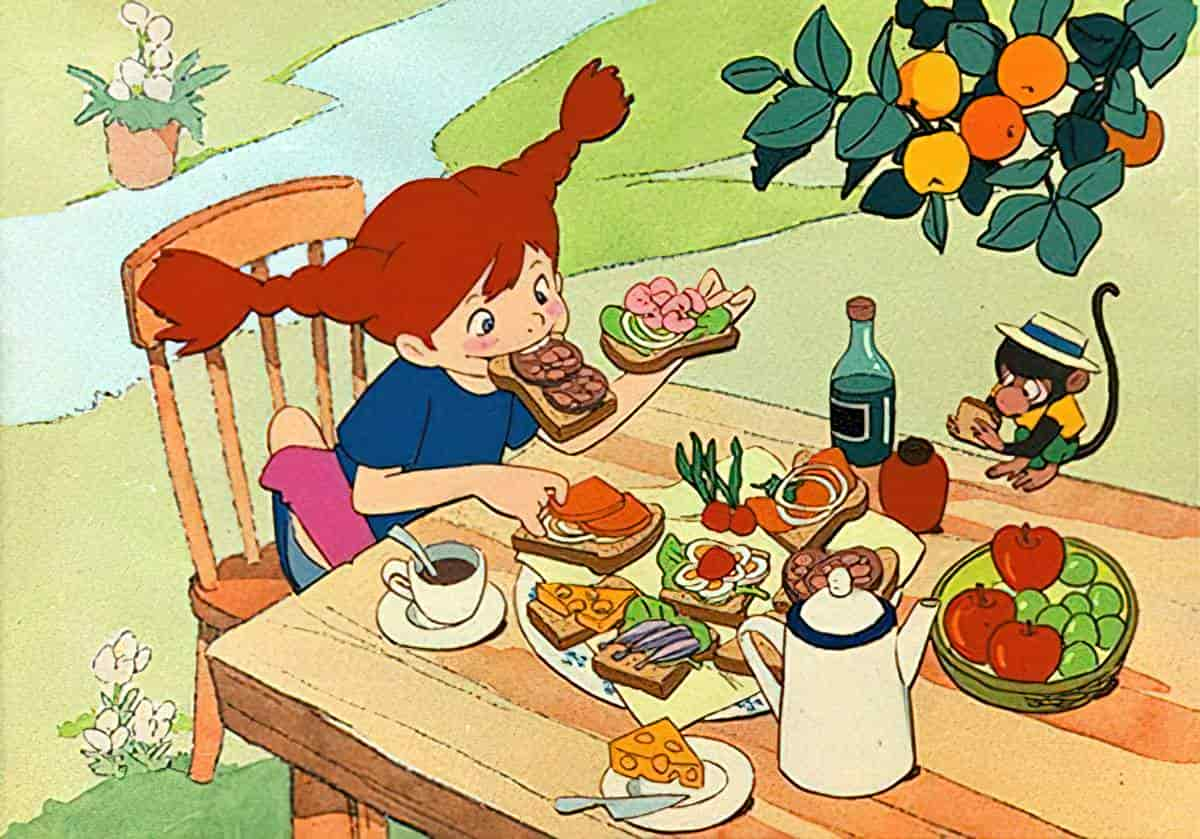

When it comes to massive food, the story conveys abundance. Examples:

Pippi Longstocking

Nikolajeva explains that we need to understand food in mythology before we can understand food in children’s literature:

According to most mythologists, meals in myths and folktales are circumlocutions of sexual intercourse, but we can reconstruct this meaning only partly from the existing texts. When folktales were incorporated into children’s literature, their motifs changed further, to suit pedagogical purposes, so that the original meaning has become still more obscure. It is therefore essential to understand what food represents in myth and folktale, before we can interpret its meaning in children’s fiction.

Maria Nikolajeva, From Mythic to Linear: Time In Children’s Literature

We are told:

The most important role of food in myths to accentuate the contrast between nature and culture. The origin of food is in nature, but it is used within culture, and it is the result of the transition from nature to culture. Thus food neutralizes this basic contrast.

Cultures are made up of many different kinds of oppositions (own/alien, male/female, home/away, sacred/profane and so on). The opposition between ‘own and alien’ tends to be especially connected to food in ancient cultures. Whatever we eat is natural and genuine; whatever others eat is alien, unnatural and unclean. This can be seen in a the big three religions. In Judaism and Islam followers are not allowed to eat certain foods. Christians have rules about Lent.

So what’s the first step when cultures start to become civilized?

Food and Christianity

Unlike most of the world’s religions, Christians are able to eat anything. Christians are omnivorous. This is reflected in children’s literature.

- The imagery of eating pervades the very language of the culture, its beliefs and its rites

- It provokes anxiety about impurity — an anxiety that used to be partly contained for Catholics, by minor rules of abstinence, such as no meat on Fridays and fasting before communion, but is no longer.

- The taboo on cannibalism — on eating your own kind—offers the apparently unbreakable standard of propriety and hence ethics. Yet it is always being broken though performance and metaphor, thus plunging the system of discrimination between the good and bad eaters into continual disarray.

- Eating and being eaten inspires one of the most common games adults play with babies. (Animal noises, gobbling — this is used in Gremlins to comic effect when the Gremlins say ‘yum yum!’)

- It’s instinctive to growl and grit your teeth and curl your fingers, as instinctive as kissing or crying.

- Faire barbo is a French expression which refers to the ancient game of clenching your teeth and grunting and making as if to claw at a little baby in fun.

Marina Warner’s take on literary cannibalism is related but a little different. Whereas Nikolajeva highlights the link between ‘eating and being eaten’, Warner highlights the link between eating one’s children and giving birth to them as another kind of ‘cycle of life’. In The Juniper Tree, the ‘birthing’ and ‘eating’ symbolism is braided all the way throughout the story. The boy gets to live on through the father. The false mother is expelled and the true father is validated. The result is a patriarchal triumph of a sort not seen in the earlier Kronos version — the female is erased entirely — the father is both birther and nurturer in the end. The family itself is reborn. Biology is negated. The dead mother has no body (and nor does the evil step-mother). The father’s link to his children is solid — and ‘link to one’s own children’ is the one thing men have never been able to take away from women, even in the most repressive and patriarchal of cultures. Instead we see it done in stories.

In short, a tale such as The Juniper Tree is all about a deep-seated question regarding family relationships:

- Who do children belong to? To mothers or to fathers? How can they belong to both?

- Who has control of the child’s identity?

The culture of primogeniture comes in here, too. This is the custom of leaving all the family wealth to the eldest child. This happened in my own extended family just one generation ago, so it’s hardly dead. It tends to happen in farming families, in which the farm would otherwise be dismantled if the assets were divided among multiple children. The idea behind primogeniture: The boy who inherits the farm provides for his extended family. (In practice this may not happen.)

Political activist Thomas Paine was against the culture of primogeniture and had this to say about it:

Aristocracy has never more than one child. The rest are begotten to be devoured.

The link between primogeniture and cannibalism is a fascinating one — metaphorical cannibalism.

Now for eroticism. There’s a fine line between love and hate. For more on that listen to the Real Crime Profile podcast with Laura Richards, a British criminal profiler and feminist activist who does a lot of work around coercive control. For women (more rarely a man), the people most likely to kill us are men who say they love us.

In that vein, Nikolajeva posits that cannibalism in storytelling can function as a sign of extreme love:

when a man (more rarely a woman) eats up his beloved, in order to own her completely. Here is once again a parallel between food and intercourse, oral and sexual satisfaction. In some myths, parents devour their children out of great love.

Nikolajeva isn’t using the term because it’s a recent concept, but she is describing ‘coercive control’.

When Women Eat Children

Think of the folktales in which a witch eats the children, or tries to. Most of the time, the children get away. Marina Warner points out that in Greek myth, there are no examples of women eating their children. Not on purpose. Nor are they duped into it. This seems a bit of an anomaly, because Greek women of myth engage in plenty of infanticide. Ancient Greeks obviously thought of mothers eating children quite separately from other methods of murder. Consider the act of eating one’s child as a kind of inverted birthing. Ownership via incorporation. This idea lingers in modern stories about giants and cannibal fathers.

From the Grimm collection, a good example of child-eating women is Hansel and Gretel. Closely related is Baba Yaga. In these tales, cannibalism symbolises death and resurrection — and a near death experience is a vital part of story structure. It comes at the end of the big struggle stage, right before the anagnorisis.When someone almost eats you, that makes for a pretty good big struggle. Or maybe someone almost eats your children. There’s only one thing worse than someone else eating your children — and that’s being tricked into eating your own children, a la the Juniper Tree tales. Again, though, these women never actually get to eat the children. She is always easily duped. The trickster children get away.

Cannibalism and Sex

Hannibal Lecter is the standout example of cannibal eroticism. But what about in stories for children? Fairytales were not for children until the Grimm brothers bowdlerised them, so bear that in mind. (It was Charles Perrault who introduced the sex-cannibal link to Little Red Riding Hood, in a wry, knowing way.)

Fairytales are about all the various initiation rites, and these rites include sexual intercourse.

The sacred food [of myth] is developed into a magical agent in folktales: bread, milk, honey, apple, beans etc. As compared to myths, folktales have lost their secret sacred meaning. Folktales collected and retold for children have often acquired the opposite meaning. It is therefore necessary to go back to myth to clarity the function of food in fairy tales, often connected with prohibition against incest. Food as a part of a trial appears in many fairy tales; the hero takes food from home when departing on his quest. Many folktales reflect the dream of Cornucopia, described as a magical mill, tablecloth or bag. Food can also be a means of enchantment, when the hero is transformed by eating or drinking something.

Maria Nikolajeva

I believe Nikolajeva is talking about food as cycle of life, which is what Marina Warner was talking about vis a vis The Juniper Tree pattern of tale. Warner also says that in these early myths, cannibalism functions as a motif to dramatize the struggle for survival within the family.

Marina Warner sees cannibalism — overall — as a metaphor for the internal states and private knowledge.

Mythic cannibals who started off as sexually indifferent grew more sexual over time. A good example of that is Polyphemus (the Greek guy with the eye in the middle of his forehead).

The Hierarchy of Cannibals

In fairytale there’s a distinction between eating someone raw or ‘as carrion’. Even better than that, cooking them is the most genteel kind of cannibalism. Sushi is one step down, followed by eating them as carrion, in which you are the worst kind of beast. (But if you are tricked into eating your own children, you’re absolved, and in fact you’ll get them back and live happily ever after.)

For the word lovers among you:

- Anthropophage — someone who eats humans

- Omophage — someone who only eats their own kind. (Well, I guess that’s okay then…)

- Infantiphage — someone who eats babies

Basically, there’s no sex in traditional children’s literature, so we have lots of food instead.

In The Rhetoric of Character In Children’s Literature, Maria Nikolajeva describes this function of food in literature by summarising Forster (1985), though numerous others have said similar:

In fiction [food] mainly has a social function; food “draws characters together, but they seldom require it physiologically, seldom enjoy it, and never digest it unless specially asked to do so”. … For all that Forster denies the characters of mainstream fiction the joys of food, they are all the more explicit in children’s fiction. … Food in children’s fiction is the equivalent of sex in the mainstream. Still more important is that for child protagonists, food is the essential link between themselves and the surrounding adults who have the power to provide food or to deny it. Food symbolizes love and care or lack thereof. A number of well-known children’s texts, from Hansel and Gretel to Where The Wild Things Are, rotate around this theme. Last but not least, food in children’s fiction is, much more often than in the mainstream, used for characterisation. James Bond may be characterized through his passion for “shaken, not stirred,” but we are more likely to remember Winnie-the-Pooh through his passion for “hunny”.

Marina Warner has this to say, after describing early childhood games in which the parent pretends to eat the child, or tuck them into bed as if putting them into an oven:

The same impulse can arise in adult love-making, but orality there is not usually accompanied by monster faces or jaw-snapping and munching sounds. In sex, the eating fantasy does not often twist and turn through comic exaggerations and parodic beastliness. As Adam Phillips has commented, ‘If…kissing could be described as aim-inhibited eating, we should also consider the more nonsensical option that eating can also be, as Freud will imply, aim-inhibited kissing.’

The interplay of these two ways of connection sometimes tilts, in the changing representations of poetry, play, images and songs, towards eating, sometimes towards kissing; in today’s climate, the public emphasis falls on food. Food may stand in for sex, the oral gratifications perhaps interchangeable at a psychic level, but in terms of shared, overt expression, the promised satisfactions of food eclipse mutual exchanges of kisses and caresses. And these satisfactions include power over the hungry, control of the consumer.

No Go the Bogeyman

Since sex and death (violence) are intertwined in mainstream stories, it is food and death which are intertwined in stories for children.

In traditional (mythic) stories, food has its own particular symbolic function:

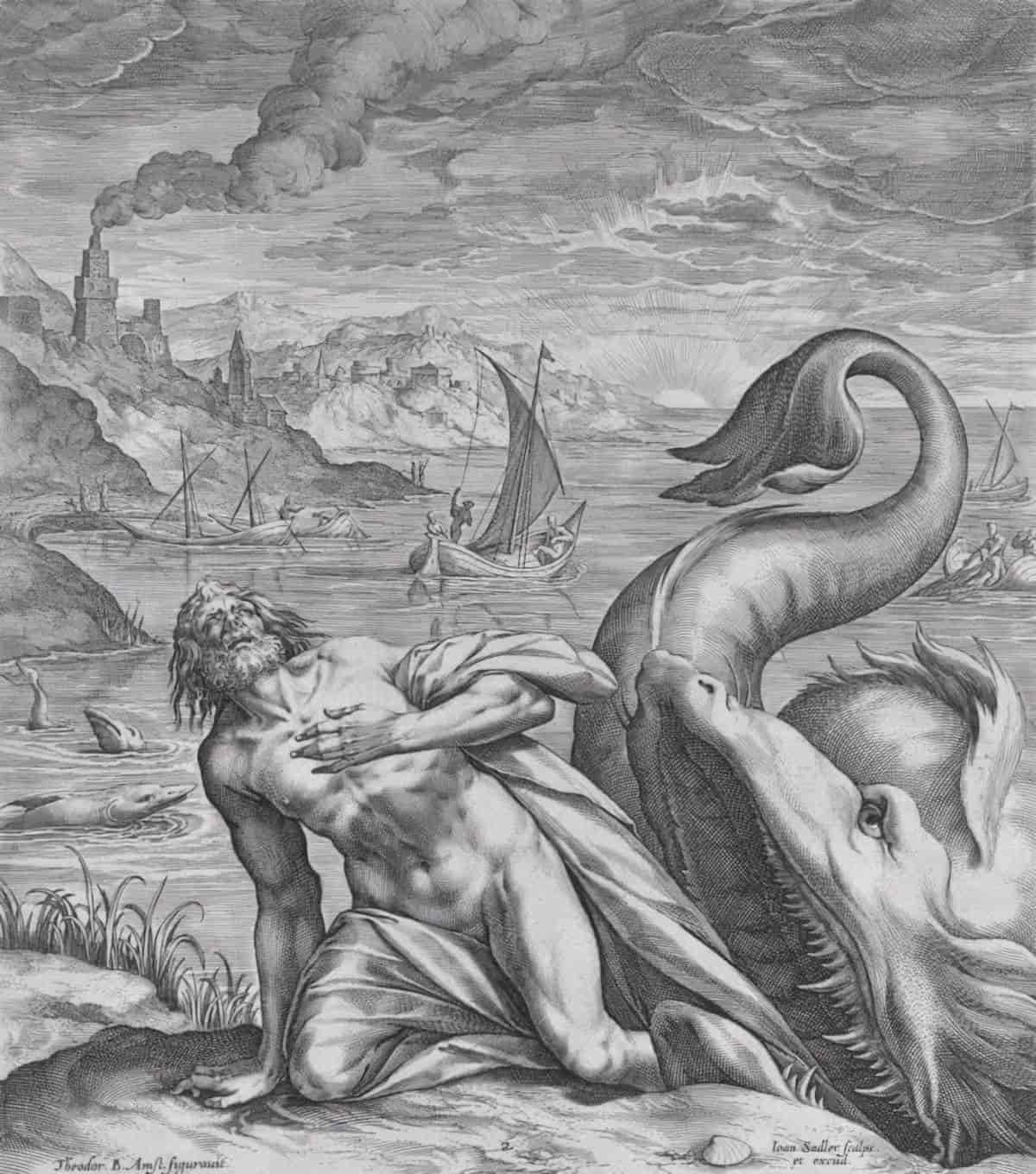

Food is an indispensable part of the initiation rite, since it is closely connected to death and resurrection. Death in a rite of passage is often represented by the novice being eaten up by a monster (Jonah and the Whale is an example), which during the rite itself is staged by the novice entering a cave or a hut (for instance the famous Russian hut on chicken legs, inhabited by Baby Yaga). Resurrection is represented by the novice being invited to participate in a meal in the Otherworld, the realm of death. By accepting food from the Otherworld, the hero gains passage into it (the Holy Communion is a remnant of this archaic rite, as is the Jewish Sabbath meal). The Russian folktale hero Ivan replies to Baba Yaga’s threats of eating him up: “What is the good of eating a tired traveller? Let me first have some food and drink and a bath.” He pronounces himself ready to accept witch food and go through a symbolic purification.

From Mythic to Linear: Time In Children’s Literature by Maria Nikolajeva

I’m reminded of Spirited Away, in which Chihiro must eat a berry in order not to disappear. When her parents eat food from this Otherworld, they turn into pigs, becoming part of this Otherworld.

“Unless you eat something from this world, you’ll vanish.”

Spirited Away

FOOD AS A LINK BACK TO THE HOME

When the character of a children’s book departs from home (a necessary part of initiation), food can serve as a link back home. Since food emphasizes affinity, “own” food, food from home is especially important. It is also important that the mother packs the food and, as in folktale, supplies it with her blessing. This security of home, represented by food, is to be found in all types of children’s fiction, including adventure books, where home is treated more like a prison.

from Mythic to Linear: Time In Children’s Literature by Maria Nikolajeva

FOOD AS A TRIAL

Since food from home gives security it can also function as a trial. When protagonists meet other characters, they are often invited to a meal or are encouraged to share their food with strangers, who become friends and helpers. In both cases, shared food is a sign of union. Food becomes a token of belonging together in a quest or struggle, or belonging to a particular group, good or evil. It can also be a passkey into the Otherworld, as in Alice In Wonderland. Finally, it can enchant, corrupt and even destroy.

from Mythic to Linear: Time In Children’s Literature by Maria Nikolajeva

…this was enchanted Turkish Delight and…anyone who had once tasted it would want more and more of it, and would even, if they were allowed, go on eating it till they killed themselves.

The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe

If that’s not a symbol for the evils of drug addiction, what is? In fact, C.S. Lewis was influenced by The Arabian Nights, in which sherbet and Turkish delight are evil confections. C.S. Lewis himself disliked these foods as a child, which together form his reason for using Turkish delight when painting young Edmond as the Judas of the story.

On the other hand, Lucy has shared food with Mr Tumnus:

During her first stay in Narnia, Lucy is invited to tea with Mr. Tumnus, the faun. He promises her “toast—and sardines—and cake”. Indeed, on the table there is “a nice brown egg, lightly boiled, for each of them” [Nikolajeva explains that during the war, eggs were rationed.] and then buttered toast, and then toast with honey, and then a sugar-topped cake.”

Nikolajeva

Did C.S. Lewis realise that what he was doing was the children’s literature equivalent of sex? Nikolajeva thinks he probably did know, but propriety prevented him from admitting it in his essay “On three ways of writing for children“.

She replied, “No more do I, it bores me to distraction. But it is what the modern child wants.” My other bit of evidence was this. In my own first story I had described at length what I thought a rather fine high tea given by a hospitable faun to the little girl who was my heroine. A man, who has children of his own, said, Ah, I see how you got to that. If you want to please grown-up readers you give them sex, so you thought to yourself, “That won’t do for children, what shall I give them instead? I know! The little blighters like plenty of good eating.” In reality, however, I myself like eating and drinking. I put in what I would have liked to read when I was a child and what I still like reading now that I am in my fifties.

C.S. Lewis

A shared meal—which we all know in its refined form as the Holy Communion—is the foremost symbol for affinity. Lewis was well-acquainted with mythology. The faun is the first person Lucy meets in Narnia. Our previous experience of stories prompts us that food comes from the good. Thus we immediately assume that the faun is a good creature. As it is, it is not totally true, since the faun is running the White Witch’s errand and tries to deceive Lucy. At the same time, the shared meal prevents the faun from turning in Lucy to his ruler. When you have broken bread with someone, you are committed. A shared meal is a covenant.

Nikolajeva

Later, the meal with the Beavers continues the affinity, showing the Beavers are friends.

“I must bring you where we can have ea real talk and also dinner”…everyone…was very glad to hear the word ‘dinner’.

In The Child That Books Built, Francis Spufford writes of the religiosity of C.S. Lewis, which obviously had an influence on his work:

Lewis took a completely orthodox but rather marginal point of Christian doctrine, and made it central to his belief. It was axiomatic that no sinful act could bring the sinner any substantial reward. You might be tempted by the idea that the sin would bring you a full, overflowing pleasure, but when you actually succumbed, you’d find out that all you got was flat, empty sensation. The apples of Sodom taste of ashes. This happened because sins were parodies, or perversions, of the legitimate pleasures God had ordained for human beings. In that case, reasoned Lewis, if you resisted sins in this life, every pleasure they held out delusively to you now, would be supplied in reality and in overwhelming abundance in the greater life to come. Every pleasure, though we might no longer recognise them as sexual once they have shed their mortal connections with biology.

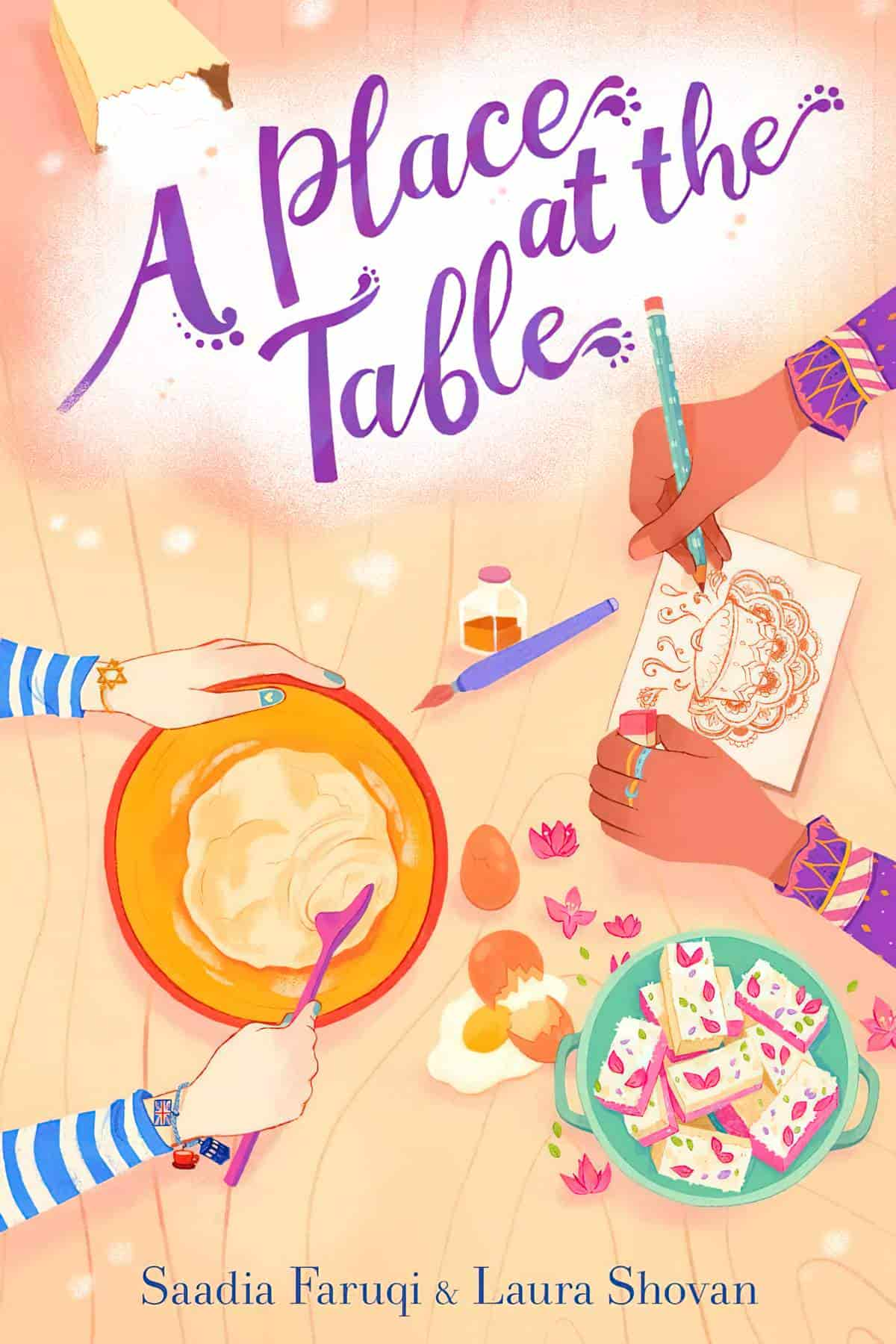

Now we’re seeing more diverse characters in children’s literature, food is being used in a different way — to bring different cultures together.

Sixth-graders Sara, a Pakistani American, and Elizabeth, a white, Jewish girl meet when they take a South Asian cooking class taught by Sara’s mom.

Sixth-graders Sara and Elizabeth could not be more different. Sara is at a new school that is huge and completely unlike the small Islamic school she used to attend. Elizabeth has her own problems: her British mum has been struggling with depression. The girls meet in an after-school South Asian cooking class, which Elizabeth takes because her mom has stopped cooking, and which Sara, who hates to cook, is forced to attend because her mother is the teacher. The girls form a shaky alliance that gradually deepens, and they make plans to create the most amazing, mouth-watering cross-cultural dish together and win a spot on a local food show. They make good cooking partners … but can they learn to trust each other enough to become true friends?

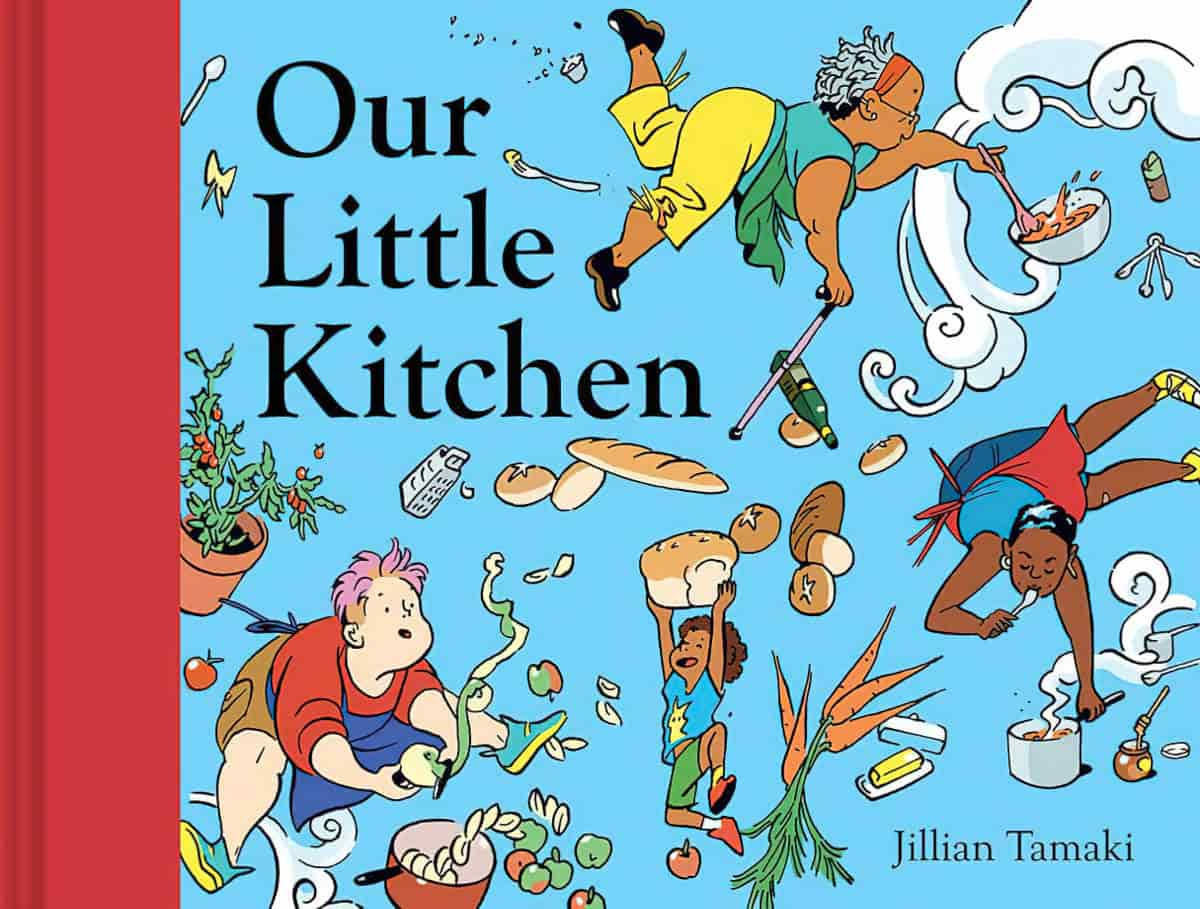

A lively celebration of food and community from Caldecott Honoree Jillian Tamaki

Tie on your apron! Roll up your sleeves!

Pans are out, oven is hot, the kitchen’s all ready!

Where do we start?

In this lively, rousing picture book from Caldecott Honoree Jillian Tamaki, a crew of resourceful neighbors comes together to prepare a meal for their community. With a garden full of produce, a joyfully chaotic kitchen, and a friendly meal shared at the table, Our Little Kitchen is a celebration of full bellies and looking out for one another. Bonus materials include recipes and an author’s note about the volunteering experience that inspired the book.

BAKHTIN’S MATERIAL BODILY PRINCIPLE

In the book Language and Ideology In Children’s Literature, John Stephens writes of so-called interrogative texts — texts which question authority, and introduces the concept of the material bodily principle:

The interrogative texts of children’s literature allow a significant space for what Bakhtin termed ‘the material bodily principle’ — the human body and its concerns with food and drink (commonly in hyperbolic forms of gluttony and deprivation), sexuality (usually displaced into questions of undress) and excretion (usually displaced into opportunities for getting dirty).

MEALS AS A MEANS OF CIVILIZATION

Stephens continues:

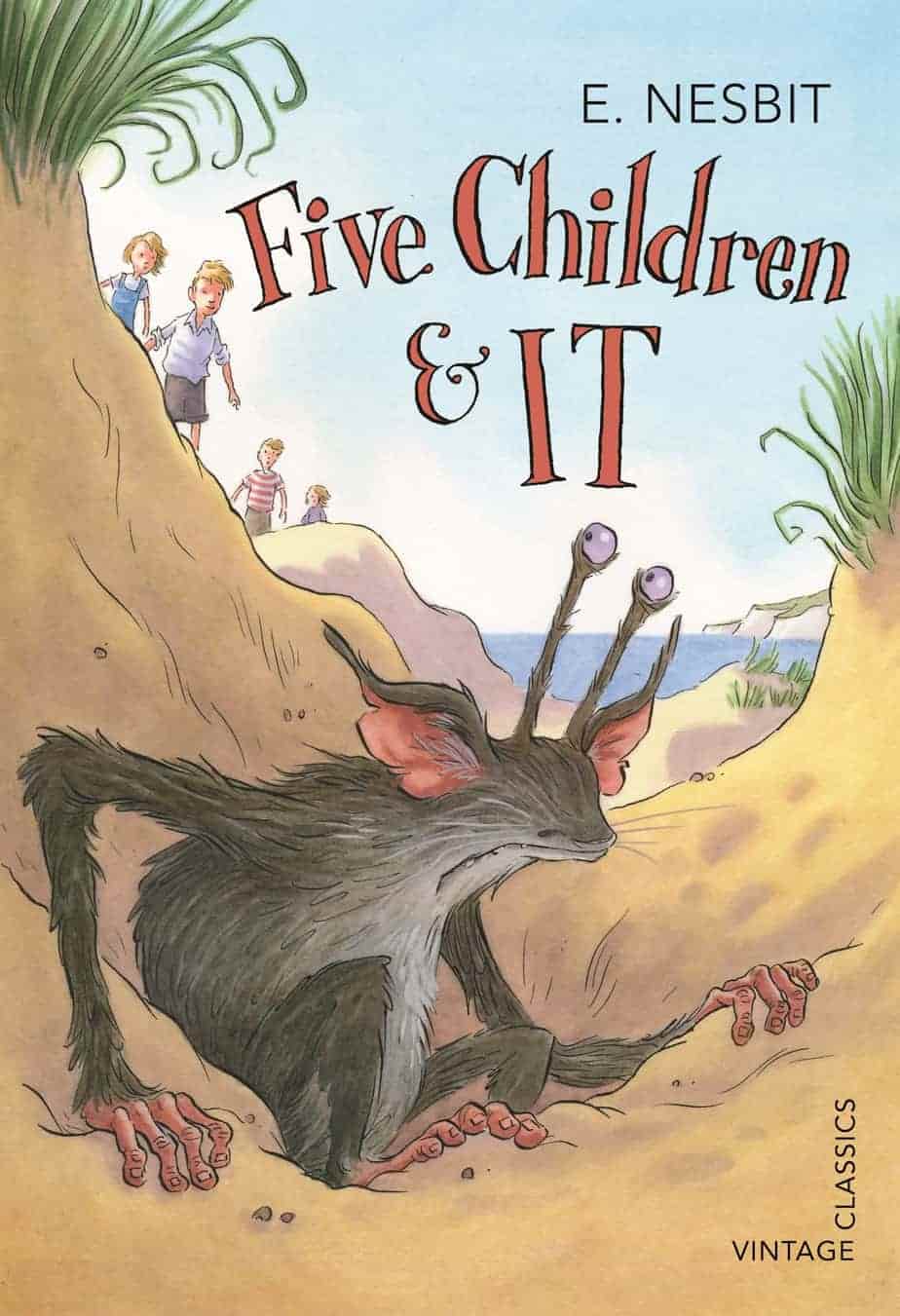

Meals and feasts, for example, are an important part of human culture, and have a unique and significant role in children’s literature. Official meals, that is, meals conducted at times and places determined by adult authority, reinforce the existing patterns of things and social hierarchies, and assert certain values as stable, normal and moral. An early reference in Five Children and It to the children being ‘caught and cleaned for tea’ discloses, despite its jokiness, the prevailing attitude that meals are part of the process whereby children are civilized and socialized in order to take their place in adult society. Katz has observed that the practice of using meals as a measure of a child’s adjustment to the social order is especially pronounced in English children’s literature. The carnivalesque children’s feast — whether ‘midnight feast’ or birthday party or food-fight — celebrates a temporary liberation from official control over the time, place and manner in which food is consumed. In Five Children and It, where food is of central concern to the main characters without being carnivalized, the baby is allowed to be revolting at mealtimes but a somewhat arch distance is maintained when the older children, compelled to eat invisible food, regress to primitive methods.

THE CONNECTION BETWEEN ANIMALS AND FOOD IN CHILDREN’S STORIES

The focus on animals and their nature may explain a[nother] common feature of children’s texts, especially those intended for younger readers. Their characters are often centrally concerned with questions about food. In well-known fairy tales, Little Red Riding Hood brings food to her grandmother but is threatened with becoming the meal herself, and Hansel and Gretel become possible meals after they nibble parts of the witch’s house. Meanwhile, Peter Rabbit has his dangerous adventure because he can’t resist Mr. McGregor’s vegetables even though his father was made into a pie by Mrs. McGregor. And In Where The Wild Things Are, Max is sent to his room because he threatens to devour his mother, discovers that the Wild Things want to eat him up because they love him, and is drawn back home by the smell of good things to eat.

Eating is less central in longer works of fiction, but it’s still an important subject. For instance, Charlotte’s Web focuses attention on descriptions of Wilbur’s slop. Charlotte’s methods of killing her food, and Templeton the rat’s pleasure in the feast available at the fair.

In these and many other texts, the fact that human beings eat creatures that once lived but were too weak to protect themselves suggests some ambiguity about the degree to which one is a human eater, like one’s parents, or an animal-like food, like the “little lambs” and “little pigs” adults so often tell children they are. The focus on eating raises the question of children’s’ animality in an especially intense way.

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature by Reimer and Nodelman

GASTRONOMIC UTOPIAS

The dream about the Land of Plenty—Cocayne or Schlarafflenland—has haunted humanity for many centuries. One of the earliest literary descriptions of this paradise is to be found in the German Hans Sachs’s verse from mid-16th century. 19th-century German picture books especially depicted travels into elaborate lands of sweets and cakes, with the inevitable didactic consequence of stomach ache.

Twentieth century children’s writers are much more liberal in their Schlaraffenland variations. The most famous contemporary tale of Schlaraffenland is Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The title itself may be seen as an allusion to early children’s books about gluttony. As in many such books, the story starts with a description of poverty and hunger. […] The big family does not starve, but “every one of them…went about from morning till night with a horrible empty feeling in their tummies.” […] The description of the Schlaraffenland matches the traditional stories: rivers and waterfalls of hot chooclate, trees and flowers of “soft, minty sugar”, a pink boat made of “an enormous boiled sweet” […] It is almost inevitable to assume that Roald Dahl read a good deal of Schlaraffenland tales as a child.

Maria Nikolajeva, From Mythic to Linear: Time in children’s literature

See also: The Wind On The Moon for another well-known story of gluttony.

Wish fulfilment fantasies about food in abundance go back to antiquity.

Food is everywhere in the Bible. From the Forbidden Fruit to the Last Supper and from the Manna in the Desert to the Feeding of the Five Thousand the Good Book is obsessed with diet. It is set in a land of milk and honey but one also faced with famine; a place of feast and fast, of drunkenness and self-denial, and of marvellous showers of bread from the skies and the transformation of water into wine. Sacrificial banquets, with bread, oil, alcohol and meat are offered to the populace, with slices reserved for the priesthood and the choicest cuts saved for the deity. Women do the cooking. Many are honoured with culinary names; that of Rebecca, mother of Joseph, means ‘cow’ and the title of Rachel, matriarch of the Twelve Tribes, can be translated as ‘ewe’.

From The Serpent’s Promise by Steve Jones

HUNGER IN CHILDREN’S STORIES

Nikolajeva explains that children have a subconscious fear of hunger, which can be used to good effect in stories.

Death as such is an abstract notion for most young readers. Hunger on the other hand is something everyone has experience, at least on a very modest scale. To be hungry, not to get food, is a tangible threat. However, it can also be translated into more symbolic notions. Hunger [can be] hunger for love and warmth.

Children of earlier eras were rarely fully satiated. As an example, this is typical food for children in the 1700s, from the menu of a London foundling hospital (orphanage):

- gruell for breakfast

- potatoes for lunch

- milk and bread for supper on Monday

- milk porridge, boiled mutton and bread on Tuesday

- broth-rice milk, bread and cheese on Wednesday

- gruel, boiled pork and bread on Thursday (And this was in pork season).

- milk porridge, dumplins, milk and bread on Friday

- Gruell, hasty puddings and bread and cheese on Saturday

- Broth, Road pork and bread on Sunday (the climax)

This menu is basic, but far better than many children got.

THE IDEOLOGY OF FAMILY MEALTIMES TOGETHER

The overriding image of a happy family round the table has remained static, fixed in the culture, as something that should happen, something that is essential to the wellbeing of the family and the nation. This is prevalent in all kinds of different media. Many Happy Returns of the Day, for example, an iconic Victorian painting (1856) by William Powell Frith, demonstrates the importance of ritual and celebration in family life, gathered together and marking occasions of private meaning. Such imagery plays a crucial part in naturalising the family meal in the same way as certain types of meals or recipes are handed down the generations and thus create tradition, nostalgia and a sense of belonging.

Cowpie, gruel and midnight feasts: food in popular children’s literature

This particular ideology may influence how things work in your own family. This post from advice columnist Captain Awkward highlights the ways in which a family can construct a narrative about What Tight Families Do, and also the problems this can lead to when adult children develop different diets.

If you take a look at various photography projects, like What Dinnertime Looks Like Around The World, you’ll get a more accurate view of how families gather for dinner.

HUNGER AND FOOD AS EMOTIONAL JUXTAPOSITION

Nothing says ‘nonchalant’ like wolfing down food. There’s no better way to make a baddie look truly psychopathic than to put him in a middle of a gruesome scene then have him pick up an apple and eat it. All the normal characters — and perhaps the audience — have churning stomachs. Yet the psychopath in question doesn’t bat an eyelid.

In this case, the juxtaposition is between the horror and the banality of satisfying a literal hunger, at the bottom of the hierarchy of needs. This most literal belly-filling hunger can also serve as a metaphor for other types of hunger: Perhaps the villain has a hunger for killing sprees or blood.

The insertion of food can also be used in different ways in fiction.

FOR COMEDIC EFFECT

‘And I like your shoes.’

He tilted his foot to examine the craftsmanship. ‘Yes. Ducker’s in The Turl. They make a wooden thingy of your foot and keep it on a shelf for ever. Thousands of them down in a basement room, and most of the people are long dead.’

‘How simply awful.’

‘I’m hungry,’ Pierrot said again.

from Atonement by Ian McEwan

MORE ABOUT FOOD IN FICTION

Food In Science Fiction: In future we will all eat lasers, from NPR

From the gingerbread house to the cornucopia: gastronomic utopia as social critique in Homecoming and The Hunger Games by Sarah Hardstaff

Fictional Characters With Food Issues from Book Riot

Food Riot, their sister website lists The Best Cakes From Children’s Literature. (Contrast this with my post on Stock-Yuck in Picture Books.)

The second half of Episode 61 of Bookrageous is about food in fiction. The hosts make reference to an article called ‘Cooked Books’ which was in the New Yorker a few years ago. The author of that explains that there are four types of food in books.

- the writers for whom dishes are essentially interchangeable, mere stops on the ribbon of narrative, signs of life and social transactions rather than specific pleasures

- the writers who dish up very particular food to their characters to show who they are. Proust is this kind of writer, and Henry James is, too.

- the writers who are so greedy that they go on at length about the things their characters are eating, or are about to eat—serving it in front of us and then snatching it from our mouths

- and then there are writers, ever more numerous, who present on the page not just the result but the whole process—not just what people eat but how they make it, exactly how much garlic is chopped, and how, and when it is placed in the pan

Which of these types of food writing is most common in children’s literature? Has this changed over time? Can you think of children’s authors who fit each of the four categories?

FURTHER READING

- Film School Rejects lists The 10 Most Gut Wrenching Meals Eaten In Movies.

- Read It Daddy has compiled a list of 3 foodie picturebooks.

- Why Do Fantasy Novels Have So Much Food? from Gastro Obscura

- A blog dedicated to food from American Gods

- Books about Hunger from the University of Miami Picturebook Database

- Biblioklept has compiled a list of Literary Recipes.

Table Lands: Food in Children’s Literature

In this this interview, Carrie Tippen talks Kara Keeling and Scott Pollard about their new book, Table Lands: Food in Children’s Literature, published June 2020 by University of Mississippi Press.

Table Lands contributes to a growing body of scholarship in the subfield of literary food studies, which combines the methods of literary analysis with the interdisciplinary theories of food, culture, and identity. Keeling and Pollard explain that they were first interested in food in children’s literature as symbols or metaphors, but in Table Lands, they have complicated their understanding of these moments as important cultural work. The didactic nature of children’s literature makes the genre a unique window into processes of cultural and identity creation as children learn manners, morals, food taboos, and appropriate behavior through the rewards and punishments doled out to fictional characters.

Arranged roughly chronologically, the chapters explore food as a cultural signifier in familiar texts for children like Winnie the Pooh, Peter Rabbit, and Little House on the Prairie, along with some less canonical texts like 19th-century cookbooks for children and Alice Waters’ books about her daughter Fanny. They range from the edgy YA series of Weetzie Bat novels to Maurice Sendak’s picture book In the Night Kitchen and the hit animated Disney-Pixar film Ratatouille. The book also attempts to represent the diversity of children’s literature in the US. The authors argue that Louise Erdrich’s Birchbark novels actively write against The Little House books which devalue, misunderstand, and erase indigenous culture to offer a counternarrative of the American West focused on Native American experiences of land stewardship and relationships to food. Similarly, the final chapter devoted to Thanhha Lai’s Inside Out and Back Again argues that Lai is writing against the representation of the refugee experience written by non-Vietnamese authors for non-Vietnamese audiences, revising and refuting what they call the “gratitude narrative” expected of refugees. Throughout Table Lands, Keeling and Pollard contextualize literary characters’ experiences with food into relevant literature on how food shapes the practice and performance of identity in everyday life.

New Books Network

Header illustration: A watercolour of a banquet by Carl Larsson