Fly Homer Fly is a 1969 picture book written and illustrated by Bill Peet who died in 2002 after a long career at Disney and in children’s books. At 64 pages, Fly Homer Fly is a lengthy picture books by modern standards. Modern picture books tend to be 32 pages, under 400 words, and read in about ten minutes. I really do think there’s still room for longer picture books such as this one in the world. Instead, it seems children old enough to sustain attention through a 64 page picture book are encouraged to read chapter books.

SENTENCE BEHIND THE STORY FLY HOMER FLY

A Town Mouse, Country Mouse mythic journey with a 1960s setting, and with birds instead of rodents.

SETTING OF FLY HOMER FLY

- PERIOD — The iterative portion of the opening takes us between seasons, showing that Homer lives by the seasons. This emphasises the cyclical nature of his life, but also the monotony. The narrative slows pacing once the storm happens.

- DURATION — a story’s length through time. Maybe it takes place over a year, cycling through each season. Maybe it takes place over 24 hours.

- LOCATION — There are three places called ‘Mammoth’ in America, but I think Mammoth City is a symbolic geographical name, mammoth simply meaning ‘very big’.

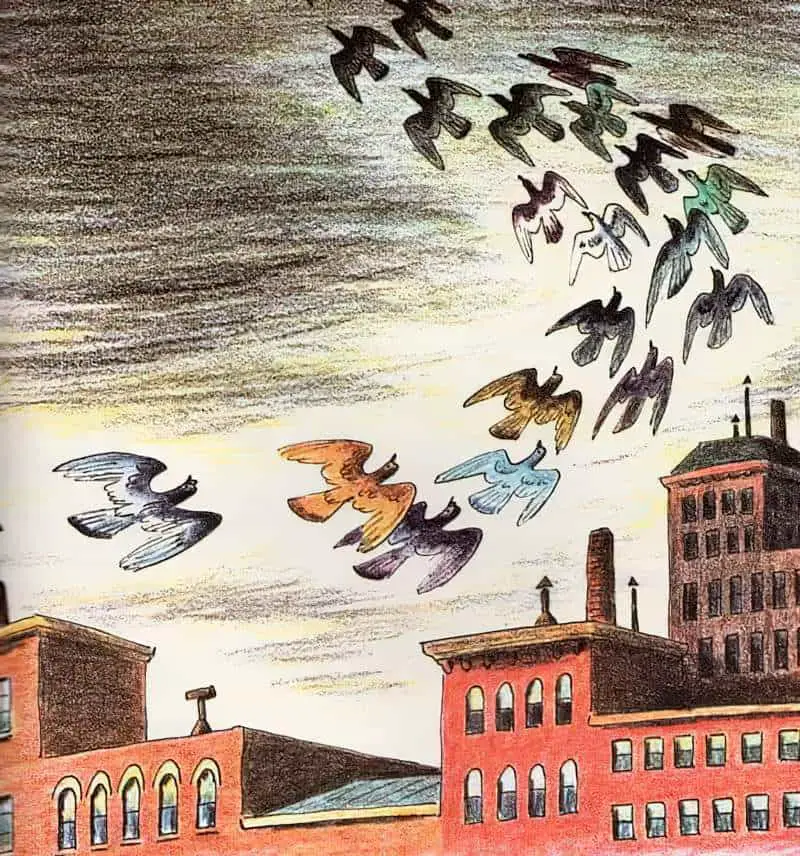

- ARENA — The story extends from the rural barn to the central city, where the promised utopia of Pigeon Plaza awaits.

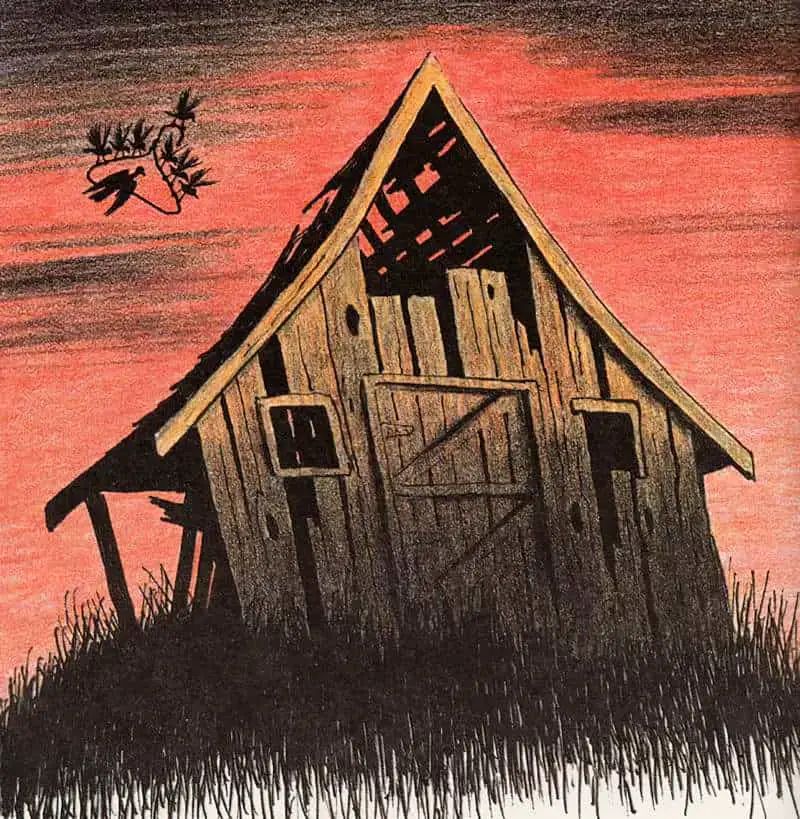

- MANMADE SPACES — Homer lives in an abandoned barn near an inhabited house where humans feed chickens every day. There is a nearby city within flying distance. In children’s stories barns are typically cosy places, similar to the kitchen in a warm family home, safe from outside trouble but sufficiently separate from the main house to afford children (or child-proxy characters) their own adventure outside the purview of adults. The barn in this story looks like a well-rendered but childlike depiction of a house, with two windows for eyes and a door as a nose.

- NATURAL SETTINGS — The country/city contrast is exaggerated in this story, with no inbetween (e.g. suburbia). The dualism of city and country is emphasised. Homer’s home in the country is utopian in that he has everything he needs, but his lodgings are an abandoned barn. This is different from the aristocratic utopia described by Kenneth Grahame. The Wind In The Willows utopia also provides the animal characters with everything they need, but some commentators accuse Grahame of elevating aristocratic luxury and thereby reinforcing the class system. Fly Homer Fly cannot be accused of this because Homer is content to return to his rundown barn which, significantly, has many holes in it, but still provides enough shelter for him (and the sparrows).

- WEATHER — The pathetic fallacy of the storm indicates things are about to change for Homer.

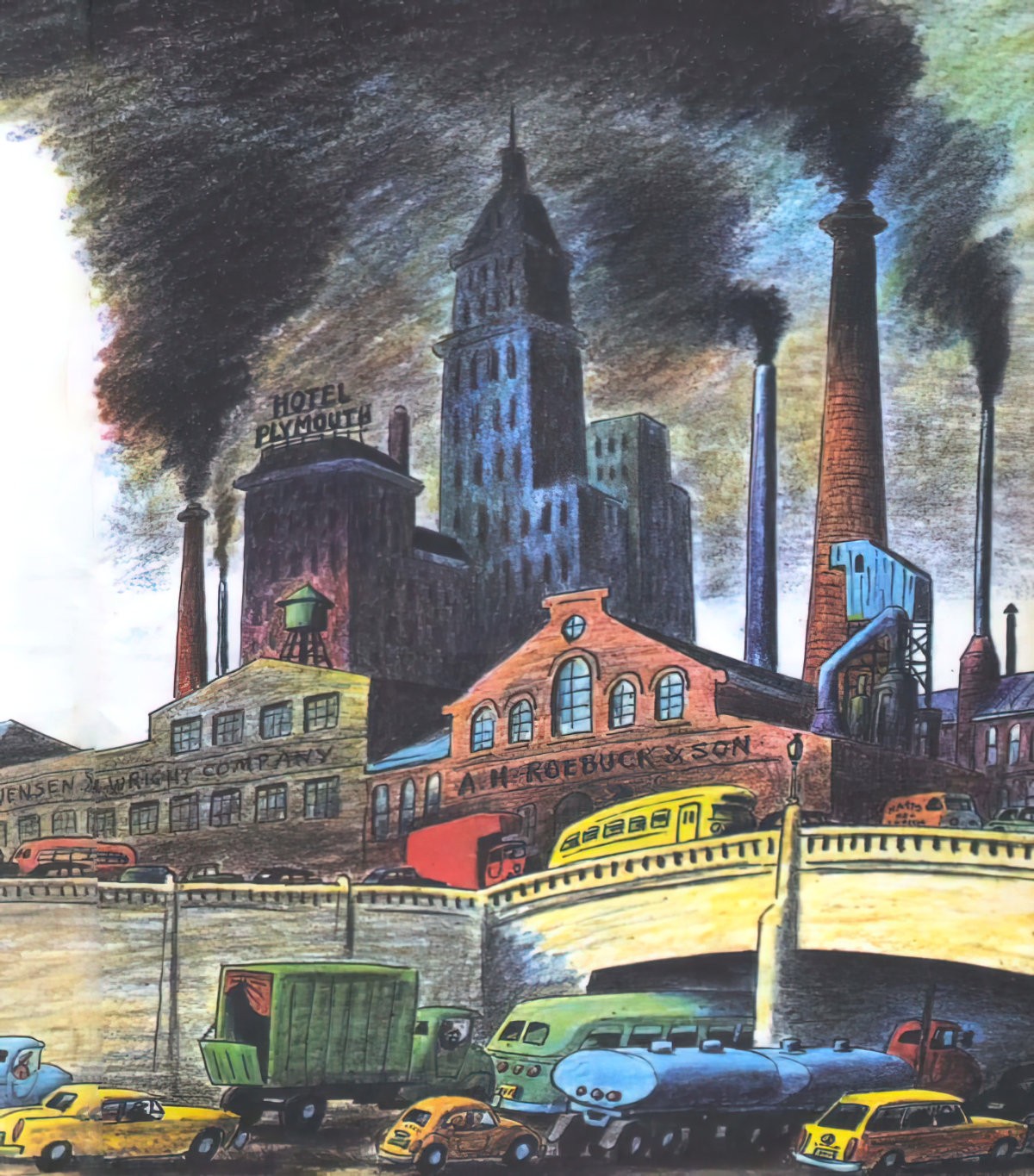

- TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO FLY HOMER FLY — Sparky has been sitting on a power line previously — a typically sparrow-like thing to do. The story includes 1960s technology which aren’t especially relevant to the birds of this story, who are more bird than human. Sure enough, powerlines are a feature of the illustrations leading the birds (and the reader’s eye) into the city. Automobiles bumper to bumper are also a symbol of urban busyness. Factories of the city create pollution which affects Homer. Their smoke darkens the sky in a city equivalent of a storm, which significantly, was over as soon as it began. (The pollution problems of cities took much longer to resolve, and are still not resolved.) A resonant image in this story is the ‘technology’ of the coat hanger, repurposed by the sparrows in a way which will

- LEVEL OF CONFLICT — The 1960s were a bad time for air pollution. A big difference between city life and rural life: the air quality. This story is clearly set somewhere in America, but an excellent example of 1960s air pollution is Japan, whose air is now of very good quality, but only after many regulations were set in place to make it so. The 1960s were a different story. I became far too familiar with the air pollution index last summer, when many parts of Australia were blanketed in smoke. We installed apps on our phones to let us know if it was safe to go outside. (It wasn’t.) This website is an excellent visual indicator of air pollution levels worldwide, and clean air is something I won’t take for granted after the Australian summer of 2019/2020. More Australians lost their lives last summer because of smoke in the air than engulfment by flame. Sadly, many people elsewhere in the world live their whole lives breathing poor quality air.

- THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE — Homer is a little bored but is content until he meets the sparrow, whose exciting name ‘Sparky’ and his enthusiastic stories suggest to Homer that unless he follows excitement he is missing out on life. The story will ultimately show that he is incorrect, because boredom and safety go together as excitement and danger go together.

STORY STRUCTURE OF FLY HOMER FLY

PARATEXT

The title page illustration shows a pigeon pecking cracked corn alongside a flock of chickens. Because he is the only pigeon in the picture we know who will be the star of the story.

Homer, a lonely country pigeon, follows his new sparrow friend to Mammoth City to find a more exciting life. He quickly learns, through several harrowing experiences, that excitement may not be what he is looking for.

marketing copy

SHORTCOMING

Homer was a simple farm pigeon who lived in an abandoned barn far out on a grassy hilltop. The ramshackle old barn had lost part of its roof and part of the wall had tumbled. Still, there was plenty of shelter for the pigeon.

The pigeon is thus established as a simple character with few needs, who doesn’t ask for much. Audiences find these characters empathetic because the inverse is a power hungry character who is never satisfied with the status quo. Although we elect these people as our leaders, they’re always the villains in stories.

Homer is clearly a pun of a name — reminiscent of homing pigeon.

This is one of those stories which starts by depicting the main character in a state of stability bordering on boredom. Homer walks around ‘lazily’. He doesn’t have to work hard to get his basic needs met.

But it’s ultimately loneliness which motivates him to change the status quo. If you’ve read enough children’s stories you’ll have gathered that from the title page. Being the only pigeon among chickens is as lonely as being the only swanling about ducklings. Also, when Homer is with other pigeons he seems to be the smallest pigeon. Lonely fictional characters are often small, as if loneliness can physically diminish you.

There’s also a storm, which comes rumbling over the countryside. The storm brings a sparrow.

If Homer fully appreciated his rural home he would never have bothered to leave it. This is the shortcoming which kicks off the mythic journey into the dark-skied, dangerous city.

DESIRE

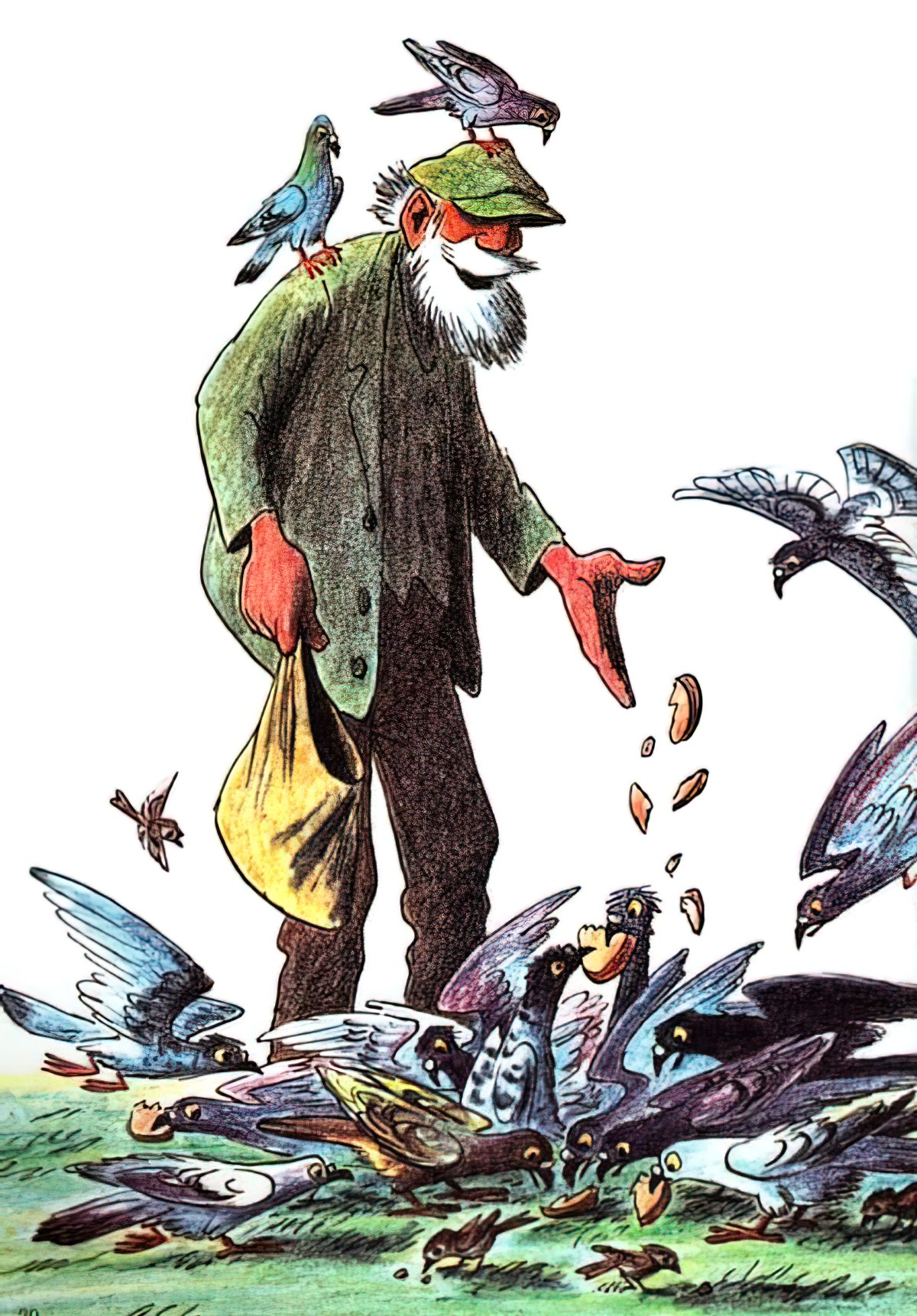

Homer’s deep desire: friendship. Unfortunately, the sparsely populated countryside leaves him bereft of pigeon friends. In the animal world of the story, Homer the pigeon is someone anthropomorphised, but the chickens are not, suggesting that the chickens will never make good companions.

OPPONENT

Sparky is an interesting character because his appearance sets off the unfortunate adventure to the city, but without that unfortunate adventure Homer would never learn to appreciate his barn in the country.

Sparky is a bit like the J.D. character of Thelma & Louise — he keeps popping up during Homer’s Odyssean mythic journey (see what else is happening with the name there?), which means the story feels less fragmented.

Unlike J.D., Sparky is not a fake-ally. His adulation of the city is genuine. He doesn’t fully understand that pigeon culture works differently there.

The pigeons of the city are clear opponents, and are reminiscent of the schoolyard bully recognisable to many young readers. Sometimes ‘your own family’ are your biggest opponents, even on a mythic journey.

The cat is the Minotaur opponent, who doesn’t scheme, is not at all humanised, and who is to be feared because of its inherently dangerous/evil nature.

PLAN

Inspired by Sparky the Sparrow, Homer plans to fly to the city to enjoy the spoils at Pigeon Plaza, where there is a never-ending supply of people feeding pigeons a never-ending supply of food.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

The battle sequence is divided into three clear components:

- The bully pigeons, in this ‘dog-eat-dog’ world of the city, where food may be plentiful but there are more characters after it.

- The wrecking ball which injures Homer’s leg

- The cat, who we know will kill him, especially with a dodgy leg.

However, the sparrow friends come to Homer’s rescue by fashioning a rescue triage out of a found coathanger.

ANAGNORISIS

The message in this story is clear: Rural life is more comfortable than city life. This is a very common ideology throughout literature and storytelling, especially in stories for children.

Bill Peet modifies this Maniachean dichotomy a little by including the rescue scene. The reason the rescue is able to happen is precisely because of the overflowing rubbish, in which sparrows find the coathanger. Though Homer does not need rescuing in the country, if he did, there would be no gang equipped with city technology to help him.

NEW SITUATION

Homer returns to convalesce at the barn and the sparrows stick around to help him and feed him bugs. By the time he is well, the sparrows have decided to stick around for good. Homer now has a gang of friends as well as a new appreciation for his humble and rustic but utopian rural life. We are told that they live happily ever after forever.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

I’m sometimes a bit envious of birds because their lives seem simple and their needs few. I’m not so sure I’d like to eat worms, but if I were a bird, I’d like worms. So that’s a moot point. In any case, I’m sure they did live perfectly happily, though I’m surely underestimating the constant manic-vigilant anxiety which surely accompanies the life of any bird.

RESONANCE

In acknowledgement of the fact that most child readers in fact live in urban and suburban areas, books which glorify the countryside even to this extent seem fewer and far between in newly published picture books for children.

That said, we still idealise rural upbringings for children. This is usually not overt, rather it comes out in our wish for children to get off screens and play outside in the fresh air with a gaggle of neighbourhood friends, free from predators such as pigeons and ‘cats’.

FURTHER READING

The Bird-Friendly City: Creating Safe Urban Habitats (Island Press, 2020),

In recent years much of his research and writing has been focused on the subject of sustainable communities and creative strategies by which cities and towns can reduce their ecological footprints, while at the same time becoming more livable and equitable places. His books that explore these issues include Biophilic Cities, Resilient Cities, and Blue Urbanism (Island Press).

In The Bird-Friendly City: Creating Safe Urban Habitats (Island Press, 2020), Timothy Beatley, a longtime advocate for intertwining the built and natural environments, takes readers on a global tour of cities that are reinventing the status quo with birds in mind. Efforts span a fascinating breadth of approaches: public education, urban planning and design, habitat restoration, architecture, art, civil disobedience, and more. Beatley shares empowering examples, including: advocates for “catios,” enclosed outdoor spaces that allow cats to enjoy backyards without being able to catch birds; a public relations campaign for vultures; and innovations in building design that balance aesthetics with preventing bird strikes.

Through these changes and the others Beatley describes, it is possible to make our urban environments more welcoming to many bird species.

INTERVIEW WITH AUTHOR AT NEW BOOKS NETWORK