When it comes to storytelling, certain themes are easy to get wrong. Attempts at subversion can end up reinforcing a culturally dominant message. Specifically, attempts to show the sexual vulnerability of teenage girls can tip into objectification in the wrong hands, or sometimes mostly by the people in charge of the marketing materials.

When Netflix advertised the film Cuties, they were widely panned for using the image on the left, below. Notice how the French theatrical poster emphasises girlhood and friendship while the Netflix poster sexually objectifies pubescent girls.

Director Maïmouna Doucouré received death threats over the Netflix Cuties poster. Unfortunately for the director, the marketing team messed up. The film is actually a “nuanced, sensitive tale of a pre-teen girl who gets caught between two cultures – her conservative, religious upbringing and the pull of her liberal French school friends who are influenced by the internet and social media.”

The thing is, marketing materials (a story’s epitext) are a work of art in their own right, and still images pulled in isolation from of a subversive story require the rest of the text to make sense, and are therefore misleading.

Marketing materials aside, others argue that the story of Cuties itself is exploitative:

To avoid abusing children in the production of the story, Doucouré could have chosen to tell the story without creating such sexually explicit material as was shown on screen, or she could have hired actors over the age of 18, but that’s not what happened.

“The audience does not need to see the very long scenes with close-up shots of the girls’ bodies; this does nothing to educate the audience on the harms of sexualization,” Lina Nealon, director of corporate and strategic initiatives at the National Center on Sexual Exploitation, said in an NCOSE statement. “Netflix could and should insist that the particularly sexually-exploitative scenes are cut from the film, or stop hosting this film at all.”

Netflix’s ‘Cuties’ Didn’t Have to Participate in Exploitation to Expose It:

That the film made it this far shows our culture is already desensitized to the hypersexualization of minors. MARY ROSE SOMARRIBA

Stories about adults can come under the same criticism. Mad Men was also criticised for seeming on the one hand to critique the misogyny of the 1950s and 60s advertising world while at the same time objectifying women.

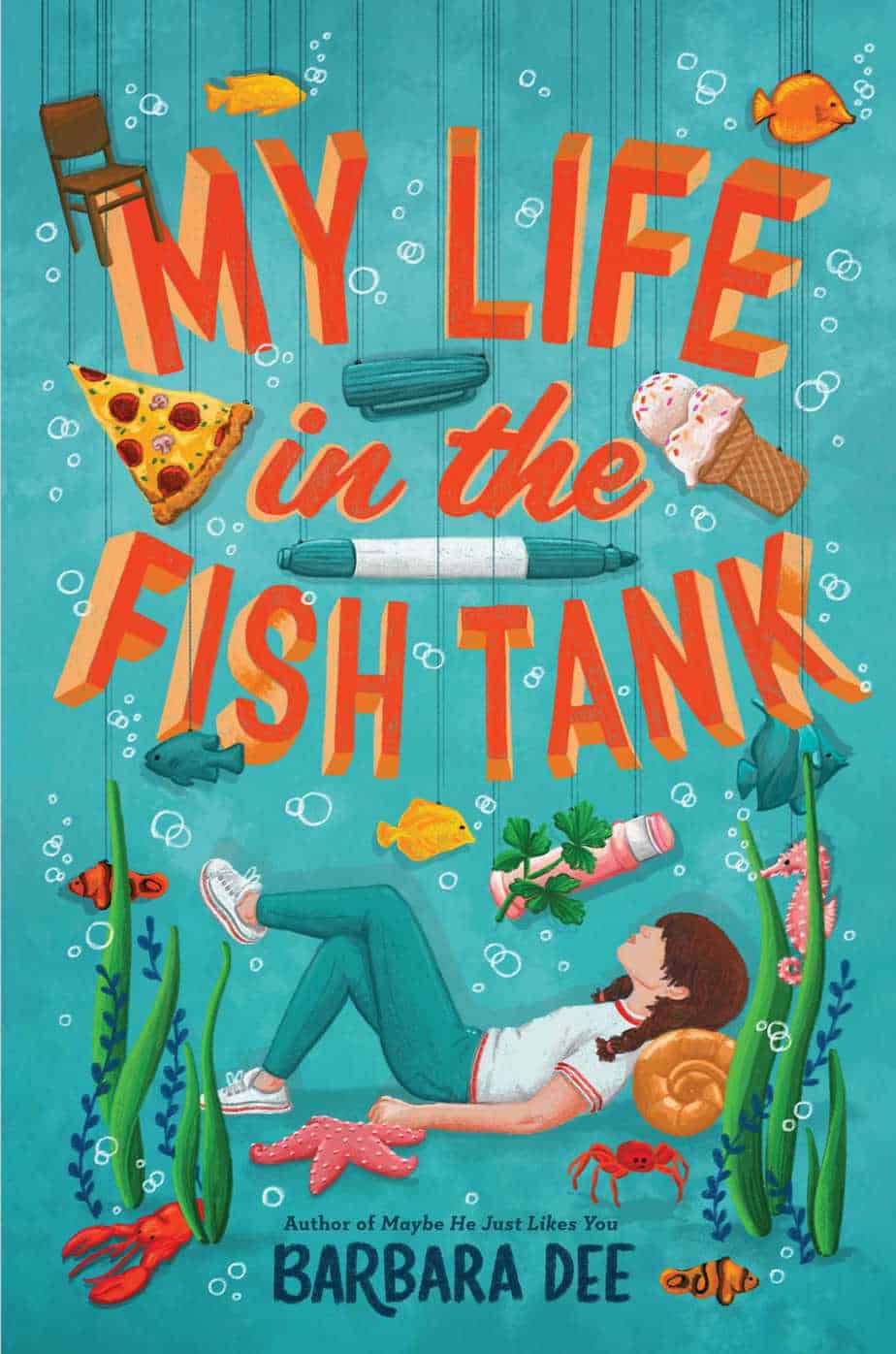

Now to Fish Tank. This is one film which does an excellent job of depicting the vulnerability of teenage girls is Fish Tank (2009) written and directed by Andrea Arnold.

I’d like to talk below about how Andrea Arnold created a desperately lonely story about a 15-year-old whose mother’s boyfriend does sex do her, without the exploitative element.

SETTING OF FISH TANK

PERIOD

2009 or thereabouts.

DURATION

A few weeks. In this time, relationships move fast. Mia’s mother brings a man home and two days later he seems to be a part of the family. To viewers, therefore, the duration may seem longer.

LOCATION

Essex, England.

What do you call an Essex girl with half a brain? Answer: Gifted! Witticisms of this kind are all that many know of England’s eighth largest county. Some are aware it’s the preferred retirement destination for East End gangsters. The refined classes shudder at accounts of its unlovely new towns, hacienda-style residences, carriage lamps, white strappy sandals and orange tans. Perhaps the majority would share Spitting Image’s view of the county as “a boil on the bum of the nation”.

David Cox, The Guardian

ARENA

When Joanne’s boyfriend Connor takes the girls on a drive to the country, it’s possible the girls have never been this far from home and this close to nature before. Mia is excited by the trip into the wilderness (and will later return on her own). Tyler and the girls’ mother are disgusted by it, and feel unsafe. They’re far more comfortable with frozen fish fingers than with actual fish, swimming in a dirty river. The irrepresible Tyler quips that if Mia goes into the river she’s likely to catch AIDs. She doesn’t understand that it’s actually people who are the real threat (when it comes to viruses and also when it comes to life). At this point, in contrast with Mia, she feels safer in her mother’s home than anywhere else.

MANMADE SPACES

Andrea Arnold originally planned to film this story near where she herself grew up, in Dartford, Kent. I taught in a Dartford high school during my Big Overseas Experience and Dartford would suit this story very well. Kent has some beautiful landscapes, but as I was told when I went for my job interview, “there are some beautiful places… not far from here (subtext: Dartford ain’t one of em, though).” Dartford is all concrete and arterial routes. If this story had been set in Dartford, Mia would’ve made a mythic journey not to the mudflats but to Bluewater, the massive mall built — eerily, I thought — in the style of an Australian mall.

But then she drove to Essex, where I later in the year worked with English language students in Chelmsford, and immediately saw the symbolic potential of the “madness of the A13, the steaming factories and the open spaces, the wilderness”.

NATURAL SETTINGS

Although Essex is known for its built-up areas populated by “chavs” and “pikeys” living in cheap tower blocks, Essex also has tidal creeks, mudflats and big skies. Andrea Arnold utilises both sides of Essex in this story. Mia lives just close enough to those tidal creeks and mudflats that it feels like she’s far away from civilisation. This is the closest she gets to the symbolic fairytale forest, a deep dive into the subconscious. England doesn’t have mile upon mile of forest anymore, but it does have this wilderness.

WEATHER

It appears to be the summer holidays, as there are plenty of kids about, mostly playing outside with each other in

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

Connor lends Mia a video camera which is as much a necessary part of the plot as it is useful to the symbolism. For the plot: Mia needs to

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

In the wider world of the story, many of the poorest people of Britain are being housed in tower blocks, because some decades ago, we collectively decided that going up rather than out was the way to go. The Wikipedia article Tower Blocks In Great Britain goes into the problems which have emerged as a result of tower blocks. The article references the work of Professor Anne Power who has written critiques of tower blocks in Europe.

Estates on the Edge (1997) recounts the decline and rescue of low-income government-sponsored housing estates across Northern Europe giving a vivid account of the intense physical, social and organisational problems facing social landlords in five countries. The ownership, management and letting patterns diverge sharply between the Continent, Britain and Ireland, between council landlords, non-profit, co-operative and independent landlords. But their community problems reveal similar trends towards poverty, polarisation and incipient breakdown. To avert the threat of incipient ghettos the stabilising pressures need to be stronger than the growing pressures towards chaos. Governments have become directly involved in estate rescue because of the vital social role estates are playing. The book traces the process of decline and renewal and shows how we can learn the lessons of policy failures and successes.

Jigsaw Cities (2007) explores Britain’s intensely urban and increasingly global communities as interlocking pieces of a complex jigsaw; they are hard to see apart yet they are deeply unequal. Jigsaw Cities examines these issues using Birmingham, Britain’s second city, as a model of pioneering urban order and as a victim of brutal Modernist planning.

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE

This is important: Andrea Arnold shows us Mia’s world through Mia’s point of view. She never deviates. In this respect, the film is similar to What Maisie Knew, a film based on Henry James’ novel. In both films, much use is made of close ups and over-the-shoulder shots and views the world either through the girl character’s eyes, or keeps the camera on her face.

Roger Ebert pointed out the camera is so close to Mia that she may be an unreliable narrator, suggesting we might read the story differently if we were allowed into the head of Amanda, Mia’s mother. This is almost certainly true. Audiences are like ducklings, and empathise with the characters we see first, and who we spend time with.

STORY STRUCTURE OF FISH TANK

PARATEXT

Everything changes for 15-year-old Mia when her mum brings home a new boyfriend.

Logline

THE TITLE

Why is the film called Fish Tank? This appears to be one of those titles which encourage a particular symbolic reading of the story, or at least points the audience in a symbolic direction.

As you watch, take a close look at the dominant colours. Aside from the drab mousey colours, oranges and blues dominate. Your archetypal fish bowl is red and orange — blue coded as water and orange for the archetypal fish found in bowls: goldfish.

Fish Tank is not a horror of a thriller, but a number of horrors and thriller stories on screen make use of a camera technique reminiscent of a big fish floating through a human community. Andrea Arnold does not make use of the ‘floating camera’ in this film, with the camera kept firmly on Mia. Mia’s world is horrific enough without borrowing the camera techniques from the scary genres. But the symbolism is clear: It’s dangerous here.

And, just as goldfish are trapped inside their glass bowls, looking to the outside but unable to escape, this story of a 15-year-old girl opens with her looking out of her window, also behind glass. Squint a bit and the Essex landscape in the distance could almost be taken for a sea floor, where the apartment blocks resemble giant kelp forests. The mist of Mia’s world suggests sunlight barely penetrates, despite the sunbathing scene to open the story and the light summer clothing of the characters.

Why ‘tank’ and not ‘bowl’? Anyone who’s owned a fish tank understands that certain fish combos are incompatible. Some fish eat other fish. Certain animals are regularly compared to the hierarchy or humans: Chickens are a common one. We often speak of ‘pecking order’ when we’re talking about humans. But when humans are compared to fish, the environment feels a bit more dangerous. There’s a risk of being consumed here. Finding her place in this world is a life and death matter for a vulnerable kid such as Mia, who has been kicked out of school, has one negligent parent and is searching desperately for her people in a community with major social and addiction problems.

Later, an actual fish becomes part of the plot. The mother’s boyfriend takes the family fishing. Mia is the only one of the family of three prepared to enter the river to help the boyfriend (Connor) catch a fish. The symbolism here is multivalent. Connor catches the fish with his bare hands, quite easily, as he’s clearly done many times before. Connor is used to ‘catching’ women (and in this case, a woman’s daughter). This is not difficult for him. Mia misreads this gesture as, “Here, I’ve got you. I’m your hunter. I’ll look after you.”

This particular symbolism again turns Mia into the fish (the prey). Disgusted by the fish Connor caught, Mia’s mother leaves it on the kitchen floor where the dog eats it. Mia is not safe in this home. Joanne is disgusted by Mia as she is disgusted by the fish.

SHORTCOMING

Mia’s shortcomings are numerous. She is violent, verbally aggressive, mean to her little sister. But the storyteller must make her empathetic. After she head butts a girl for doing nothing more than dancing in public, Mia runs to where she knows a white horse is chained up. Mia tries to set the skinny white horse free. She fails and is chased away, but the Save The Cat moment does the job: Mia is the horse. She feels bad for the horse because she, too, is a wild creature wanting to break free.

Then the camera follows Mia home and we meet her mother, probably about 30 and very much like an adolescent herself, ill-equipped to deal with a teenage daughter. Mia talks to her little sister the way the mother talks to her. Shit travels down.

We empathise with Mia because she is clearly lonely and also neglected.

DESIRE

Mia is an uncommonly isolated character. Her loneliness is what makes her so vulnerable.

But a deep, human need like loneliness isn’t quite enough to drive a story. To give the plot some extra narrative drive, Andrea Arnold has given Mia something which will sustain the plot of this particular part of Mia’s life: The dance opportunity. It’s especially helpful to a story when there’s some big event with a countdown timer, and for Mia, this is it.

For wider plot purposes, this ‘subplot’ of the dance audition ultimately tells the audience that a kid like Mia is being let down by various unconnected groups. Also, she needs a video camera, and this she borrows from Connor.

In stories for and about young adults, photography is often an integral part of the story, for various thematic reasons. Cameras are also very useful to plots, because they leave evidence. The video camera will come in useful later, as it allows Mia to learn that Connor has a daughter of his own.

OPPONENT

Everyone in Mia’s life is an opponent, though for viewers unused to this culture, the combative mode of communication may seem more combative than it actually is. Mia and her little sister Tyler are closer than their constant arguing would suggest. This is only revealed at the end of the film when the sisters hug while continuing to swap insults.

Mia’s mother Joanne has no redeeming qualities. Audiences will judge any woman harshly for prioritising parties and sex above her own children. This is all a writer needs to do to turn a mother into a monster. There aren’t many mothers like this in children’s literature. The bad mothers of children’s stories tend to love their children despite their addictions and their own personal problems (see the stories of Jacqueline Wilson, sometimes set in environments like this). But it’s quite possible Amanda really doesn’t think much of Mia, or that any love for her once has gone.

Amanda is slightly kinder to Tyler and I suspect she was slightly kinder to Mia before Mia went through adolescence and became, to Joanne’s mind, a sexual competitor.

Michael Fassbender does a great job of signalling to the audience that he is untrustworthy. An adult audience will be expecting the turn of events, which makes it all the more horrific to watch. Mia is in clear need of a father figure, and at first Connor seems a likely candidate.

When Connor puts Mia to bed and removes her trousers, this is functioning like the ‘jump scare’ typical of horror movies. The audience waits for the man to reveal himself as a monster, but then he leaves the room. Okay, thinks Mia, more awake than he’s letting on. He’s not interested in me like that. I’m safe. There was nothing to be worried about after all. I’m so stupid for thinking a monster had infiltrated the house. This is the function of the horror jump scare, and this is why Fish Tank is a horror movie without actually being a horror movie.

Connor leaves Mia to sleep and the audience is left in suspense. We know this man shouldn’t have so much as touched the girl’s trousers. But could we be wrong about him, too? Are we wrong to be wary of all men?

The sad irony for Mia is that the people she thinks can help her are the very people who don’t, and the woman who visits the house wanting to send Mia away is coded by Mia as the main opposition. Meanwhile, a middle class audience may well be thinking, “Going away for some special education and intervention is the best thing that could happen to Mia.”

PLAN

Connor is a sexual predator, or at least an opportunist.

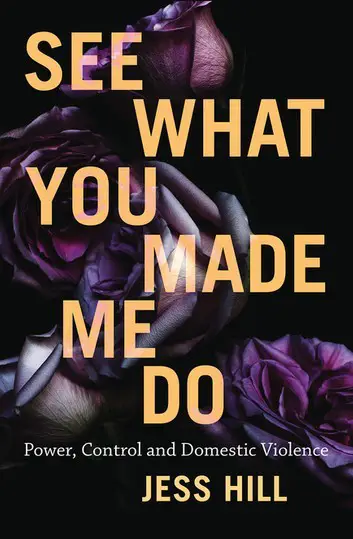

Roger Ebert calls the guy an ‘opportunistic, amoral’ character rather than a pedophile and my take is similar. But I am also reading See What You Made Me Do by Jess Hill at the moment, about domestic abuse. Jess Hill points out that some men know they are abusers and their campaign of control is very deliberate. There are even online communities dedicated to teaching each other how to control a woman. Others are equally abusive but don’t have much (or any) idea about how dangerous they are.

Women are abused or killed by their partners at astonishing rates: in Australia, almost 17 per cent of women over the age of fifteen – one in six – have been abused by an intimate partner.

In this confronting and deeply researched account, journalist Jess Hill uncovers the ways in which abusers exert control in the darkest – and most intimate – ways imaginable. She asks: What do we know about perpetrators? Why is it so hard to leave? What does successful intervention look like?

What emerges is not only a searing investigation of the violence so many women experience, but a dissection of how that violence can be enabled and reinforced by the judicial system we trust to protect us.

Combining exhaustive research with riveting storytelling, See What You Made Me Do dismantles the flawed logic of victim-blaming and challenges everything you thought you knew about domestic and family violence.

The type of grooming we see in this film is the most typical, despite a common misconception. One of the few studies we have about sexual abuse of children found that in 82% of cases the offender was a “heterosexual partner of a relative of the child”. Openly gay offenders accounted for only 3.1% of cases.

I put Connor in the latter category. There’s no evidence in the story that he deliberately targeted Joanne knowing that Joanne would allow him access to a teenage daughter, but because the camera (narration) stays so close to Mia, we can’t possibly know this for sure. This ambiguity mimics reality. Like any abuse situation, outsiders can never know for sure exactly what’s been going on inside the perpetrator’s mind.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

This entire film is a ‘struggle’ because Mia’s world is combatative. She’s been battling her entire life. But for storytelling purposes, this scene (or sequence) refers to the near death battle which leads to the main character’s self-revelation.

I have noticed before that sometimes when filmmakers try to create a sympathetic story about a young woman who is raped, the camera suddenly switches and we see her from the rapist’s point of view. It would be far more harrowing in a rape scene to show the rapist’s hairy nostrils, say, the way he pins the audience (in victim position) down. However, this is clearly seen as too harrowing for audiences and is rarely done. (On the page, Arthur Golden does a good job of this in Memoirs of a Geisha.)

It’s not immediately clear that when Mia breaks into a house that she is breaking into Connor’s house. He’s done sex to her, and perhaps unwittingly forged an emotional relationship. Now he starts to have some clue about what he’s done and how it’s at risk of getting him into trouble — possibly with the law — and he’s retreated. Mia knows his home address from going through his wallet and reading his pay slip (I guess).

This scene is a little Goldilocks, in the same way any girl entering someone’s house while they’re not there is going to be reminiscent of Goldilocks and the Three Bears (notice there are three inhabitants of Connor’s home). There’s always a risk that the owner will return, and they will be, to Mia, as dangerous as wild bears.

Why does Mia pee on the carpet? First, this unexpected act makes for resonant detail. I’ve seen this film a number of times and this scene is one that sticks in my mind.

Clearly it’s an act of revenge. Connor’s partner will wonder who did it. It also functions as pre-battle preparation. Mia is about to enter the deepest part of her psyche. She’s more literally about to make a journey across Essex wilderness, which turns her symbolically into a wild animal. Peeing on the floor is an animalistic thing to do, and calls back to the earlier image of the white horse, who Mia has likewise emotionally connected to after knowing very little about it (foreshadowing her vulnerability to falling in love with the father figure who penetrates her, both emotionally and physically).

When Mia abducts Kiera, Connor’s real daughter, the audience doesn’t ever learn what Mia had in mind for her. Was it the revenge of a fright, a hot-headed completely unplanned act of defiance, or something far darker?

Symbolically, Mia is taking her own younger self into the wilderness (her subconscious). Kiera has the father that Mia thought she briefly had. But the two girls are bound together in his badness: Kiera is too young to know that her father’s an immoral, opportunistic root rat, but in being let down by Connor in disappointing father role, these two are one and the same.

When Kiera falls into the water and almost drowns, Mia’s conscience kicks in and she fishes the girl out. (Again with the fish symbolism.)

ANAGNORISIS

By saving Connor’s young daughter from drowning, Mia is saving herself. When she snaps out of her rage and extends kindness to Kiera, she is extending kindness to herself, who she now sees as a vulnerable child. The abduction of Kiera and the unempathetic dragging of the girl through wilderness is exactly how Mia herself has been treated her entire life. She had learned to treat herself in this way.

Now that Mia has extended some kindness to a younger version of herself, she seems to have realised that kindness exists in the world, and now she must go outside the ‘fish tank’ to find it.

NEW SITUATION

Because Mia only knows combative relationships, she’s earlier in the story become attracted to the boy with the horse who scavenges car parts for a living, and whose first encounter with Mia was a dangerous one. (He let go of his fighting dog, which chased Mia away from the area.) A naive reading of Mia would be that she returned to the boy because she is masochistic, but we now know a lot more about victims living under violence. We can deduce that Mia returns to the scene partly because she is trying to process the danger. To amerliorate the trauma, she returns hoping to find something less dangerous this time, to replace the earlier memory. Andrea Arnold is sure to reward Mia for this act in this particular story, which should tell the audience victims are occasionally somewhat rewarded for this (in the short term). We should therefore be more understanding of women and children who, to us, appear to an outsider to be acting in a masochistic fashion, drawn constantly back into danger.

Significantly, this young man reveals to Mia that the horse is now dead. Mia hasn’t died in this story, but there have been a few different spiritual deaths.

Mia finally breaks down and cries. The two are now bound together, and Mia takes off with this boy to Wales on some further dodgy car parts business.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Before she leaves, there’s a moving dance scene in the living room, in which Mia’s mother finally shows a little humanity by dancing with Mia and Tyler to one of Mia’s CDs, which Mia is leaving behind for her mother, as if in a will.

The audience can deduce from this gift that Mia’s departure is final. She won’t be coming back to live with her mother and sister, and even if she does, she won’t be the same person.

RESONANCE

Andrea Arnold has since made another film about a teenage girl in a similarly vulnerable position, but this time she went to America to make it. Fish Tank features the song California Dreaming — a song which is ultimately ruined for Mia when she realises the dance audition is for a completely different kind of dance. America, on the other side of the Atlantic, stands for distant dreams in general.

But when Arnold went to America to make American Honey there is no ‘distant romantic notion of America’ for kids who actually live in America. Instead they have The American Dream up close and personal, and by roaming all over the country these disenfranchised kids can see for themselves that there’s no way out of their lives. The film ends with the suggestion that this story won’t end.

Like the main actor of Fish Tank, Arnold scouted the main actor of American Honey from a public venue and paired her with a veteran older male actor. In the case of Fish Tank it was Michael Fassbender; in Americna Honey it was Shia LaBeouf, who is perhaps a little too close in real life to the scoundrel he plays on screen.

In both films, Andrea Arnold proved an excellent scout, because both of the inexperienced young actors successfully carried the stories, alongside equally unexperienced casts of minor characters from their native milieux.

These two great examples aside, our narrative landscape remains disproportionatly short on nuanced stories about the vulnerability of disenfranchised young women. Perhaps it requires an #ownvoices (female) director to create such stories without accidentally objectifying the very subjects storytellers hope the audience will better understand.♦

FURTHER READING

The Verticality edition of the Sociological Review Magazine (online), which includes articles such as “Moving on up? The downside to the high life in Buenos Aires social housing” and “Smart cities or bad ideas: Is urban verticality meeting anyone’s needs?”

Estate Regeneration: Learning from the Past, Housing Communities of the Future

One hundred years ago, the Addison Act created the circumstances for the large scale construction of municipal housing in the UK. This would lead to the most prolific phases of housing estate building the country has ever seen. The legacy of this historic period has been tackled for the last twenty-five years as these estates began to suffer from misguided allocation policies, systemic building and fabric failure and financial austerity. A series of estate regeneration programs sought to rectify the mistakes of the past.

Estate Regeneration: Learning from the Past, Housing Communities of the Future (Routledge, 2020) describes 24 of these regeneration schemes from across the UK and the design philosophy and resident engagement which formed each new community. A number of essays from a wide range of industry experts amplify the learning experience from some key estate regeneration initiatives and provide observations on the broader issues of this sector of the housing market. Regeneration is inevitable; it is a matter of the form which regeneration should take. The information presented here is a guide to an intuitive approach to estate regeneration which commences with the derivation of strong urban design principles and is guided by real community engagement. The experience presented seeks to learn from the mistakes of the past to create the best possible platform for regeneration of the housing estates of the future.

interview at New Books Network