Written by Alejandro Amenábar, The Others is an old-fashioned melodramatic ghost story but done very well. If you haven’t seen it yet, it’s one of those films that can be ruined in one fell swoop (like Sixth Sense), so leave the building now!

Amenábar is also well known for Open Your Eyes, and he started in filmmaking very young. He both wrote and directed The Others. (Screenplay)

This is a ‘haunted house movie’ (see here for an extensive list of many others) of the genres thriller and horror.

Remember that horror is one of the most metaphorical of genres, so there will be messages behind the story that you have to dig for a little bit.

On Twist Endings

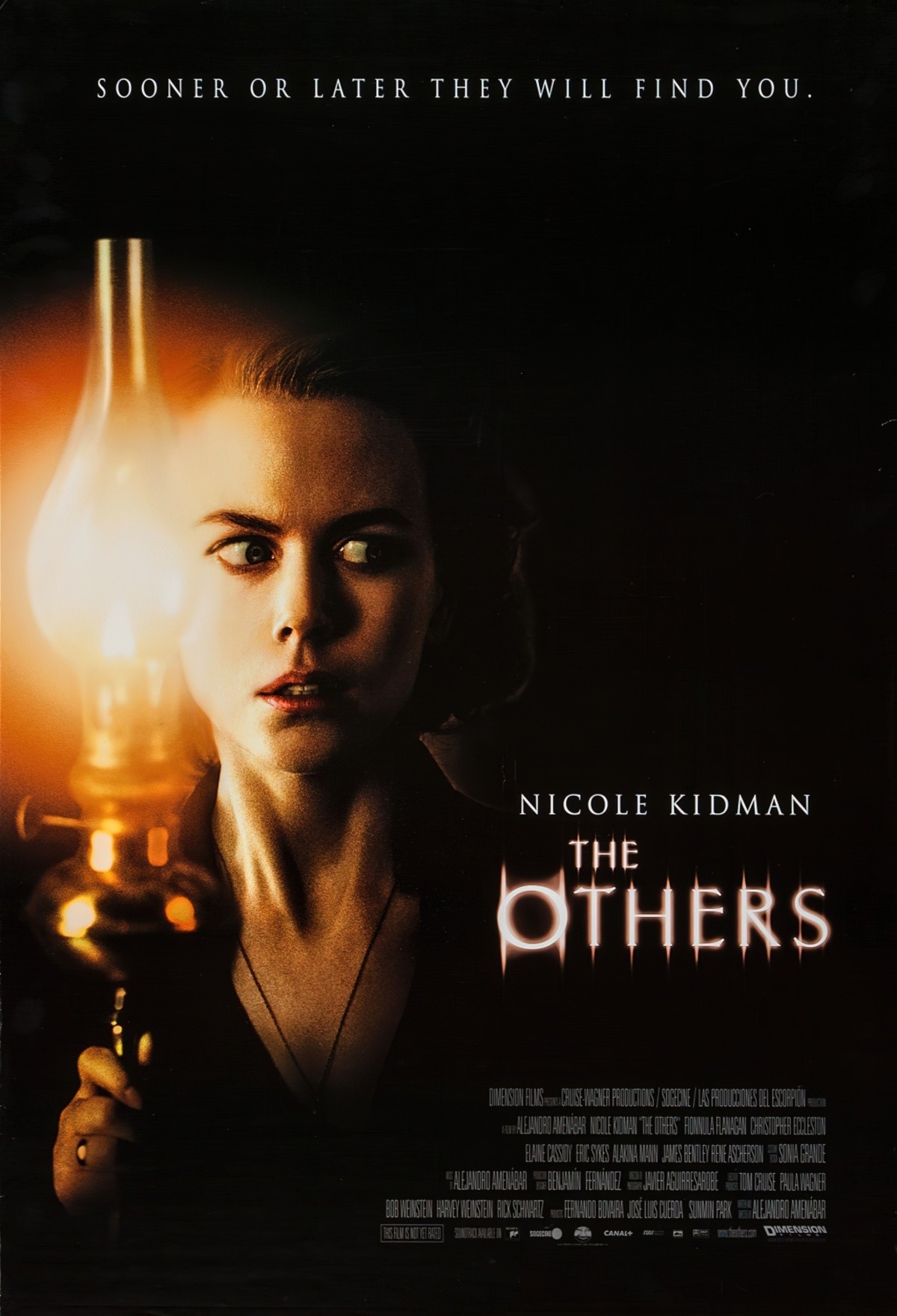

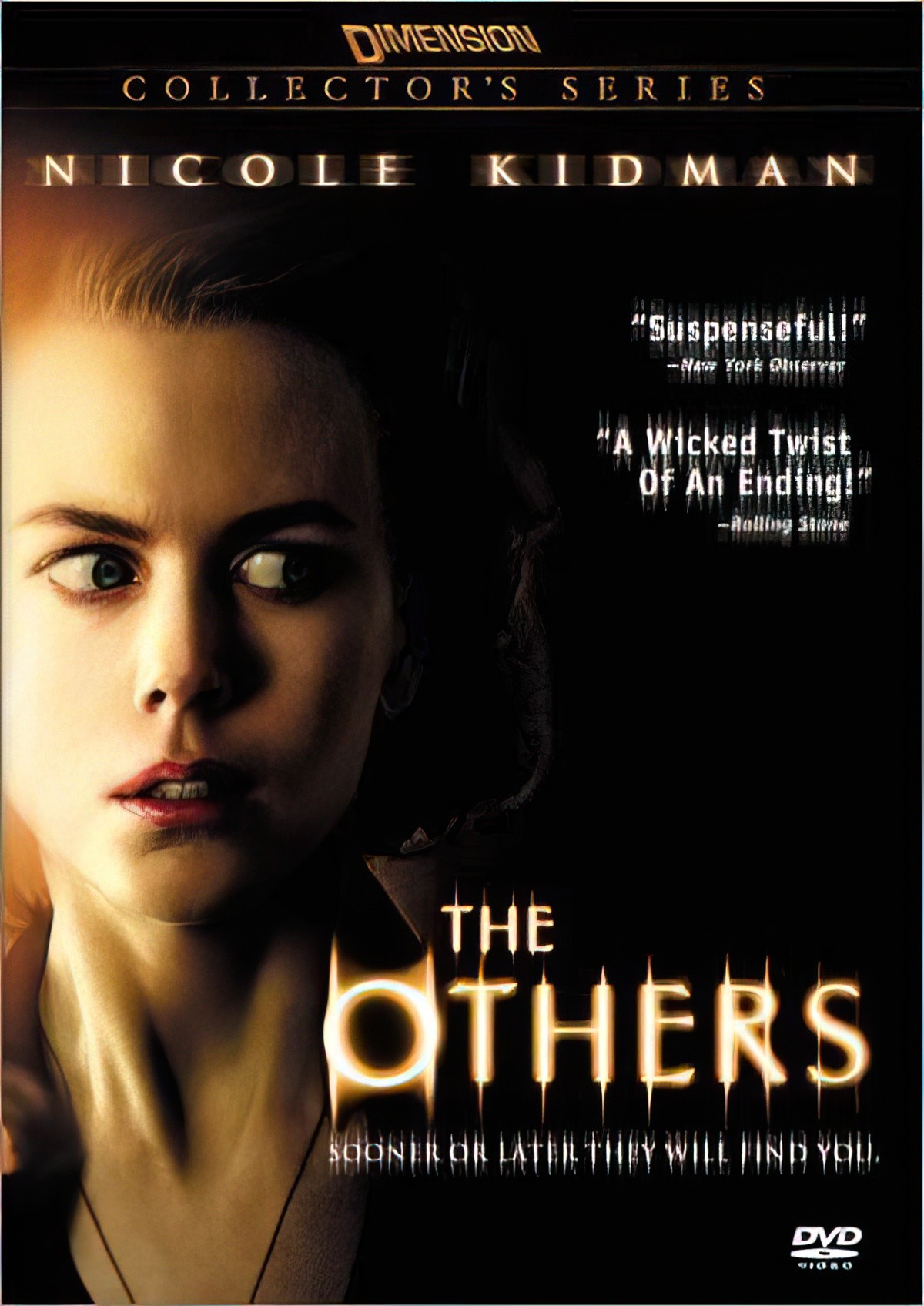

Now that you know this film has a twist ending, it’s worth noting that just telling someone to expect a twist ending changes the story experience. You’re always better off not knowing a twist ending is coming. Take a look at the movie poster compared to the DVD collector’s edition, in which it is assumed that anyone buying the DVD will have already seen the film and know the twist. Note that, even though twist endings might at first glance make a great selling point, that information is kept off movie posters:

Other films with twist endings:

- Seven

- Signs

- The Village

- Saw

- The Stepford Wives

- Terminator 3

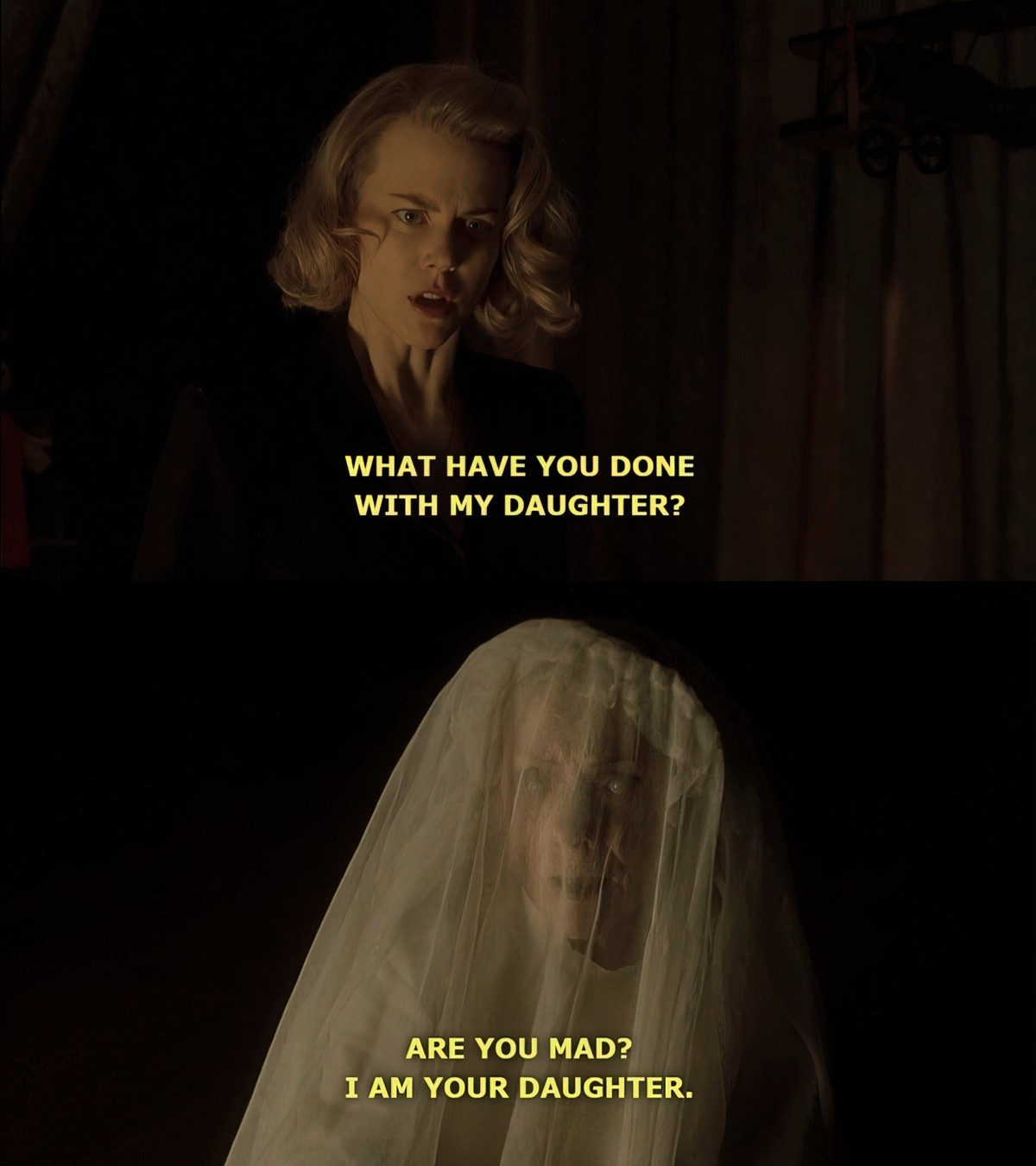

- Flightplan

Agatha Christie mastered the art of twist endings. Twist endings are almost mandatory in mysteries such as those she wrote. She managed this by setting up false villains. This is the trick employed by Amenábar here, too. Something which has been done so often that it’s almost cliche is when the audience finds out the main hero is already dead. This is done here too, after a fashion, but because we’ve also been tricked into thinking the villains are the troupe of house servants, the story still offers surprise: We probably suspect the house servants are ghosts, but we’re less likely to think the mother and her children are also ghosts. And even if we do guess that (because we’re super literate and have experienced a lot of stories), it is probably still a revelation to learn that it was the mother who killed her own children. Being a wartime setting, we probably assumed they died from some sort of war tragedy, or the Spanish flu (which killed more people during the war than did the battlefields.)

In short, the surprise twist in this story work because there is a layering of reveals — there is not just the one surprise.

This is difficult to pull off because it requires the writer to predict the audience’s response in order to confound it.

Tagline

A woman who lives in a darkened old house with her two photosensitive children becomes convinced that her family home is haunted.

Genres: Thriller, horror. Remember that horror is one of the most metaphorical of genres, so there will be messages behind the story that you have to dig for a little bit. The story opens with a mother telling her children the story of Genesis. According to her religious (Catholic) world view, the afterlife is divided into parts: heaven, hell and purgatory. She believes this all the while failing to understand her reality within the story: Life on earth is likewise divided into parts — the living and the dead. Earth has its own kind of limbo, and it turns out to have nothing to do with whether someone has been baptised or not (as she has told her daughter, Anne.)

The Others is influenced by German Expressionism, an art movement dating from around 1900 until the early 1920s. German expressionist artists had often been to war, and came back a little world weary. The art they made was about the wretchedness of modern urban life, the solace of nature and religion, the naked body and its potential to signify primal emotion, and the need to confront the devastating experience of WW1. German expressionist art aims to startle the viewer. It is frank and direct. If you watch a German expressionist film you’ll find:

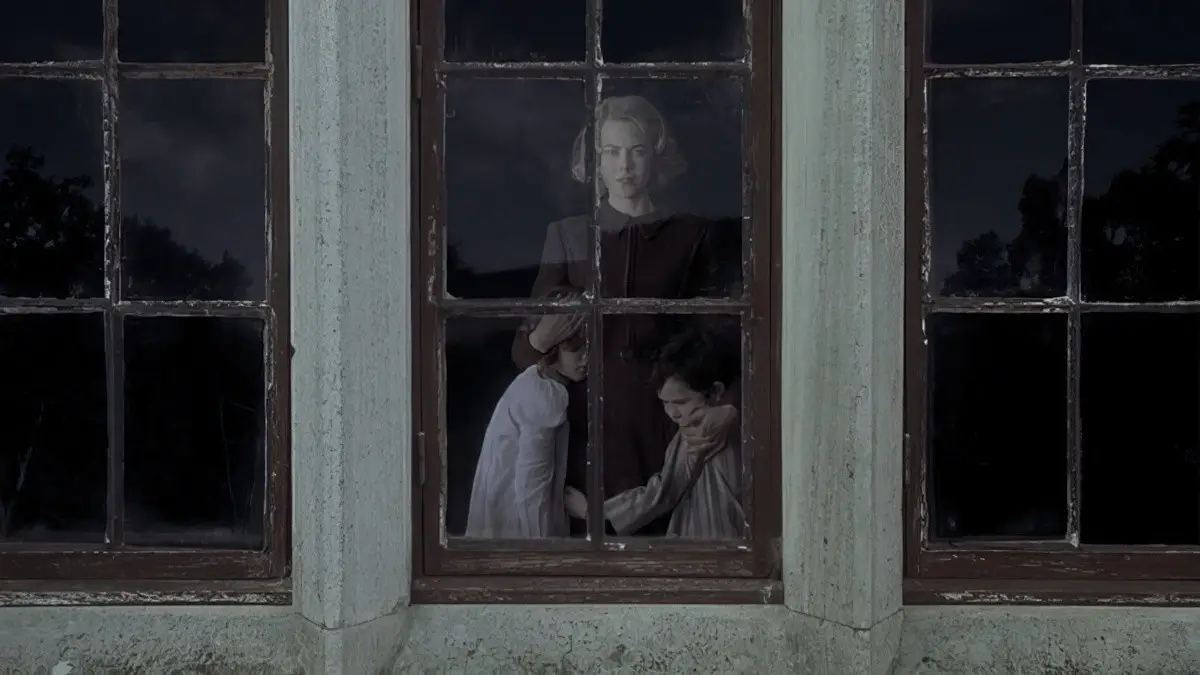

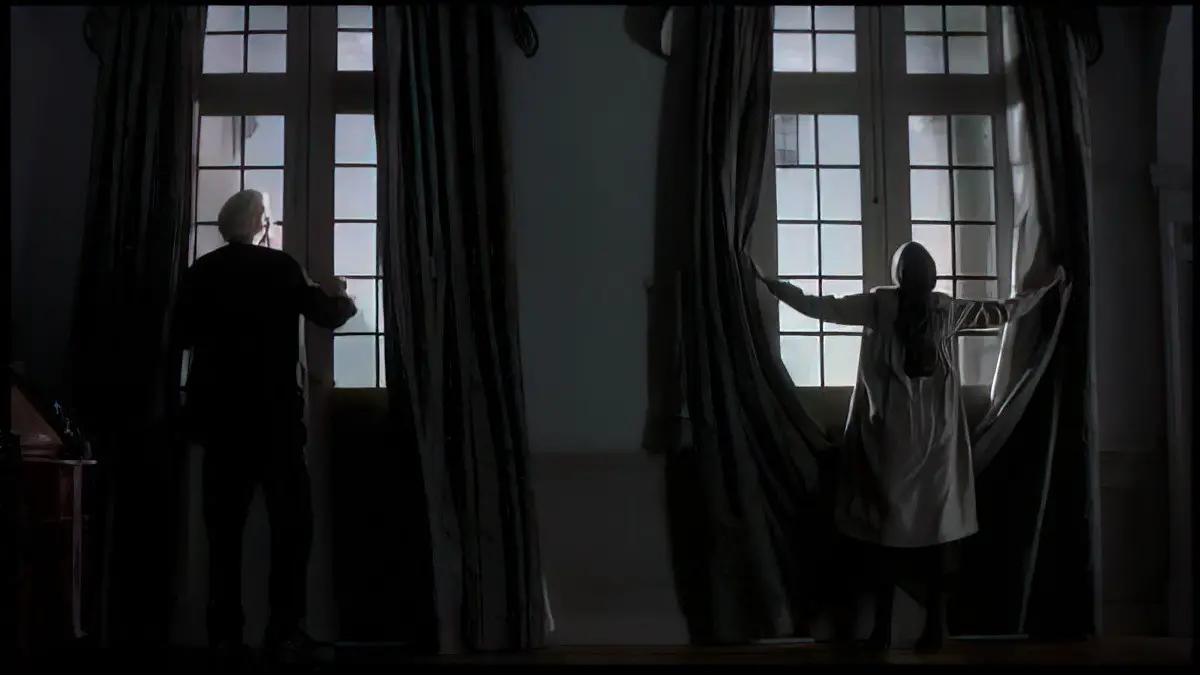

Chiaroscuro lighting — extreme contrasts of dark and light can be seen in this film as the characters move between dark/light rooms, often illuminated by only a kerosene lamp.

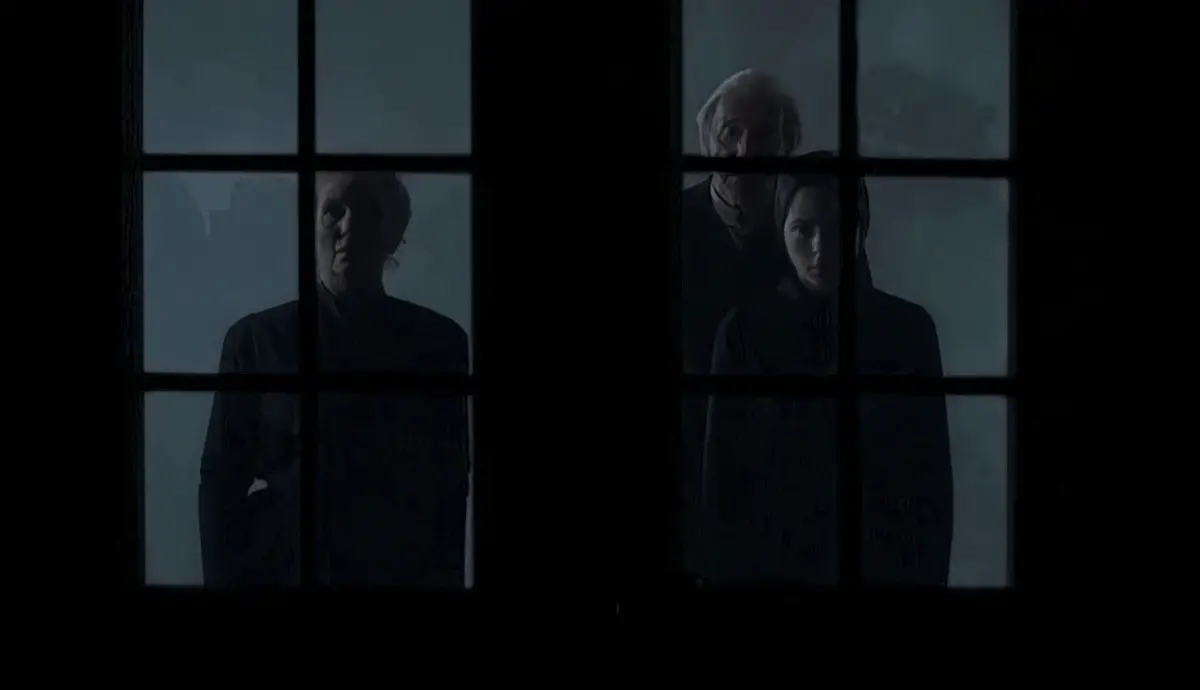

Lots of mirrors, glass and other reflective surfaces — in this film mirrors and windows come to the fore

Anthropomorphism — in this ghost story we have a similar thing: possession. (Little girl turns into old woman.) In a haunted house movie the house itself often functions as a character in its own right. The puppet Anne (and the old woman) play with is an anthropomorphised visual representation of this double world, where one has a hold over the other. But which world is more influential? In the end, the spirit world win out — the real world people drive away, unable to get rid of the ghosts.

I think (as Roger Ebert pointed out) this story is a ‘waiting game’. Unlike some of the most popular and memorable films, this one has a largely passive main character, whose only real motivation is to do nothing and keep the status quo. This was perhaps the writer’s biggest challenge. The writer also had to be very careful about the reveals, saving the one big reveal right until the very end. This meant that there could be no dramatic irony or anything like that — the audience has to be kept in the dark for as long as the main character is kept in the dark. This suspense bored Roger Ebert, who no doubt could guess what was going to happen due to having seen so many films; other fans absolutely loved the atmosphere regardless.

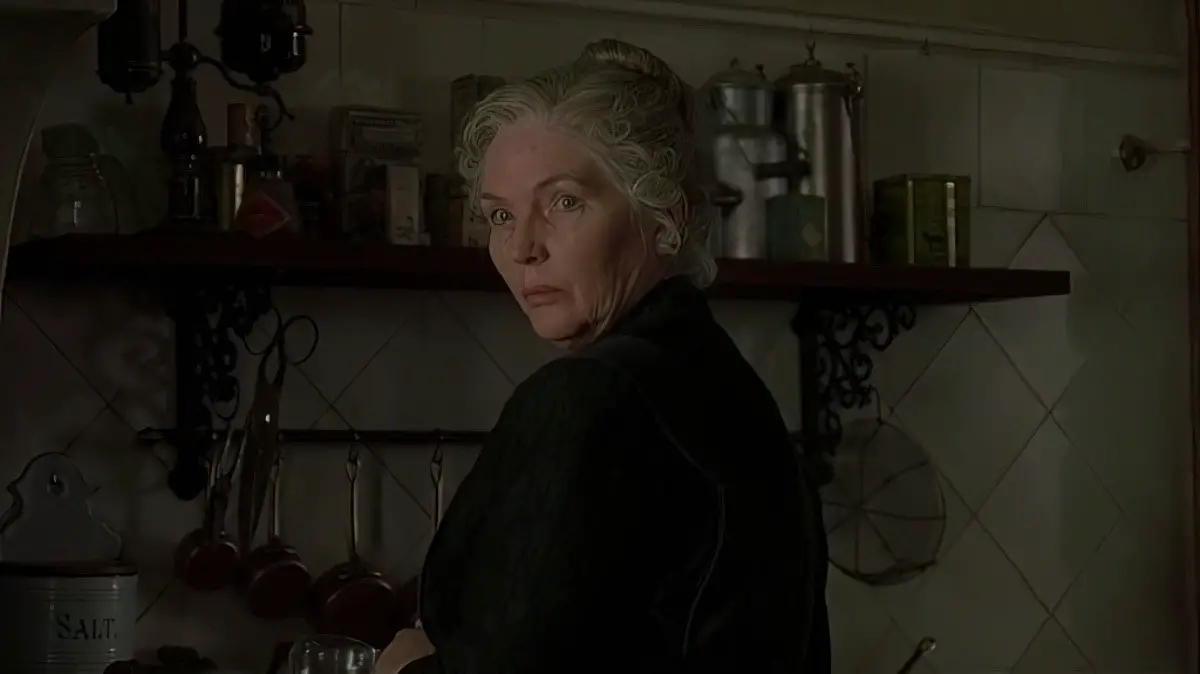

Why do some critics think this story drags? I think the story might seem slow because both Grace and her fake-opponent ally Mrs Mills were both waiting for each other to reveal themselves. Usually, you’ve got a driven hero and an equally driven opponent. The real opponents, who are very driven to rid their house of ghosts, are unseen by the audience, which is another problem the writer had to overcome.

Anagnorisis, need, desire

At the end of this story Grace will realise she is dead. She thinks she is still alive. She needs to realise she is dead before she can begin to ‘live’ her death. But the death is really a metaphor for the one terrible thing she did to her children — the killing could be compared to anything which damages a relationship irreparably, from which there’s no going back.

At the end Grace will also realise that she killed her own children as well as herself. This is part of her mending her relationship with them in their shared death. (They’re going to be stuck here, in this house, forever together… When I realised this I felt terribly sad for those child ghosts! Though apologies from parent to child can mend relationships, saying sorry cannot mend psychological damage.)

But here at the beginning of the story Grace thinks she is alive. She can’t work out why her servants left without so much as collecting their pay cheque, and she thinks that although she got mad and smothered her children with pillows, that she did no lasting damage, because all she remembers is that she walked back in on them and they were playing happily with said pillows.

backstory

This is the perfect story to use when illustrating the concept of the ‘ghost’ in storytelling, because this is literally a ghost story, but even if the main character hadn’t happened to have died, there is still the issue of that one day: We’re not told immediately (only after the father comes back — we learn he has asked the daughter about ‘that day’) but something terrible happened right before this story timeline began. By the time we’re told what it was we’ve already sensed it. The ‘ghost’, of course, is that Grace went mad and smothered her children to death with pillows before killing herself with the shot gun. We’ve already seen by that point in the story that the mother is controlling and mean, and that she owns a rifle. (Chekhov’s actual gun.)

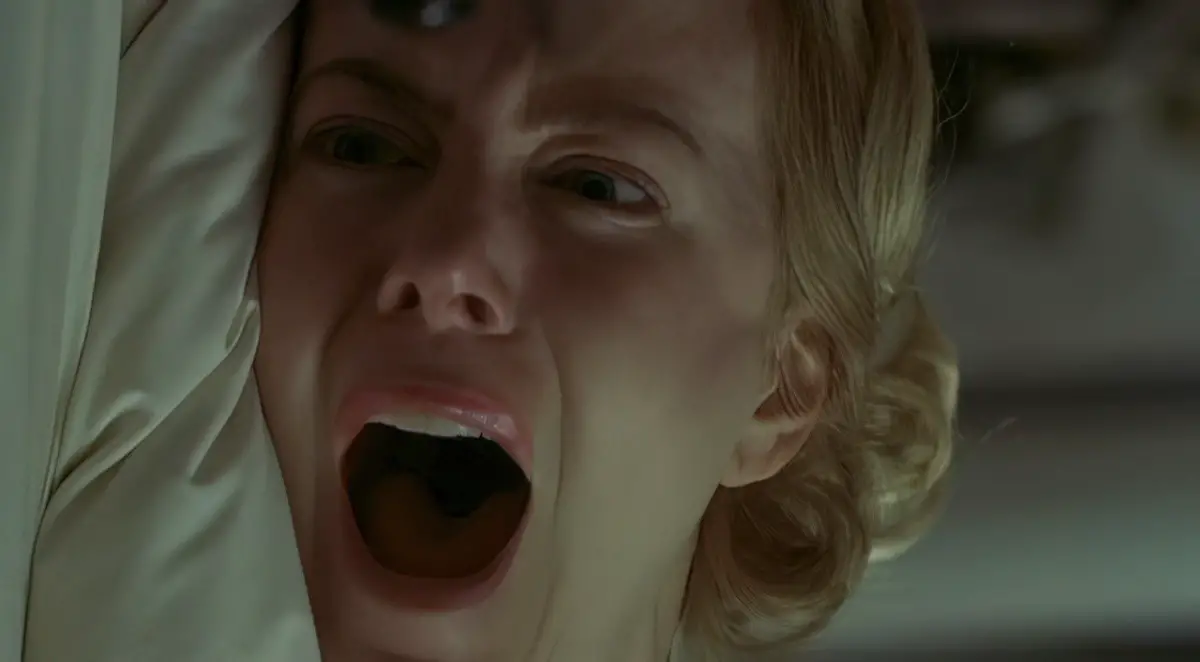

The first question the audience has (although I personally forgot about it altogether until I went back): Why does Grace scream?

Setting

The post-wartime Isle of Jersey setting works very well for this particular story, partly because modern technology would prove a big problem for the basic plot. This is a family who needs to exist in a big house with no electricity. The darkness of the house is explained away at the beginning when Grace explains to the house servants that there were so many electricity cuts during the war that they just ‘learned to live without it’. There’s also the photosensitivity issue to get around the other problem — children generally play outside, and these ones don’t.

This era was also the height of the ghost story, sometimes called ‘The Golden Age of the Ghost Story’ (between the decline of the Gothic novel in the 1930s until the start of the first world war.)

There’s also a convenient reason for the father to be absent, and for him to be dead. He needs to be dead if he is to appear as a character in the story, and wars are great for that. Or is he just in a coma? The father’s semi-comatose state in this movie suggests that maybe he is lying injured somewhere on a battlefield, and when he leaves it’s because he’s returned to the land of the living. (In which case, is he the next person to arrive at the house? Will the children be haunted by the ghost of their own dad?)

For a 2001 audience, the wartime setting feels sufficiently ‘old-timey’ to suit the ghost story’s mood — after that even aristocratic families in and around England were no longer living in gothic castles on the misty moors — they were starting to open up their homes to the public in order to pay for maintenance on their historic homes, and the English aristocracy had changed to the point where the super rich could no longer live as they had been.

Another problem the writer had to overcome was: How to limit the arena to just this castle and the surrounding forest? He did this by use of mist. (A widespread belief concerning ghosts is that they are composed of a misty, airy, or subtle material.) Grace mentions at one point that ‘The fog has never lasted this long before’. In the ghost world that this writer has created, ghosts are surrounded by a white gloom, and can never escape beyond the place where they have an emotional attachment. This works really well. This boundary is tested of course, when Grace tries to leave and gets disorientated. (She finds her husband at that point, who seems to have been wandering around in a fugue state looking for home.)

This island has a long and interesting history, and would therefore have interesting ghosts. (Its recorded history extends over 1000 years. Jersey was part of the Duchy of Normandy, who’s dukes went on to become kings of England from 1066. Although it’s closer geographically to France than to England, it has remained attached to the English crown.)

Other problems the writer would have had to think about in this particular story: How to supply a family of ghosts with food? If ghosts don’t eat, wouldn’t they notice this fact? He gets around this by including a breakfast scene early in the story in which the daughter, Anne, eats toast but says it tastes funny, not like before. We — and the new housekeeper — interpret this to mean that the previous cook made better toast, and that Anne is simply having trouble adjusting to the change of personnel. But on second viewing, this is foreshadowing — she’s having trouble adjusting to being dead in general.

Other supplies such as Grace’s migraine tablets and kerosene are conceivably in generous supply at the house and haven’t run out over the course of the storytelling.

Haunted houses have a long history in literature, which is referred to throughout the film by Anne, literature in such tales, who has therefore concluded that ghosts walk around in chains. She would have been influenced by stories such as:

- The Castle of Otranto (1764) by Horace Walpole

- The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) by Ann Radcliffe

- “The Fall of the House of Usher” (1845) by Edgar Allan Poe

- The House of the Seven Gables (1851) by Nathaniel Hawthorne

- The Turn of the Screw (1898) by Henry James

- The House on the Borderland (1908) by William Hope Hodgson

- The Rats in the Walls (1924) by H. P. Lovecraft

This house is Victorian in style, just as the mother has Victorian values about child-rearing and a literal interpretation of the bible.

Shortcoming & Need (Problem)

Psychological Shortcoming: Grace is unable to relate warmly to her own children (or indeed to anyone else) and, as it turns out, she sometimes goes over the edge into insanity. We see this when Anne is possessed by the old lady from the other side.

Moral Shortcoming: Grace is controlling and mean — she is the trope of the cold, pre-war English mother who believes children should be seen and not heard. She is motivated by the Bible and doesn’t question even its most disturbing parts. She believes all evil will be punished in hell and using this as her motivation she can be unjustly cruel on her children, particularly on her daughter Anne. We see this when she makes Anne sit on the stairs for three days reading from the bible. The housekeeper questions the severity of the punishment. (Anne has been seeing ghosts.) Grace also treats her servants harshly, and doesn’t believe that she herself might have made a mistake such as leave a door open. She doesn’t believe people even when they’re telling the truth.

Need: Grace needs to put aside the bible and experience spirituality for herself — there’s no telling this woman.

Inciting Incident

Anne has seen some ghosts and draws pictures of them — not that Grace believes this. She punishes her daughter for making up stories.

This inciting incident connects need and desire by showing the audience how Grace can’t accept experience — this contrasts with her reading the bible (in the very opening sequence) — she is a woman of words but not of experience. She can’t ‘feel’ anything.

Desire

Grace’s goal in this story is to live in this big, dark house undisturbed by the outside world, protecting her (supposedly) photosensitive children from sunlight. She is the perfect character to become a ghost without knowing it because all she wants to do is keep her children locked up in the dark. (I suspect the mother was actually agoraphobic, otherwise she would have surely memorised the names on the graves right outside her own house and realised who the servants were as soon as they turned up. I suspect Grace impressed this agoraphobia onto her own children by telling them they were photosensitive when they weren’t.)

The importance of this desire increases over the course of the story due to the ‘ghosts’ making this impossible, escalating of course when they’ve taken down the curtains altogether. (Probably because they were freaked out by them — the actual ghosts were always going around closing them during the day.)

Ally/Allies

The housekeeper Mrs Bertha Mills is a fake-opponent ally. Her desire in this story is to show Grace the truth and provide her support when she comes to her realisation that she is dead. But she seems to Grace (and also to the audience) to be deliberately undermining Grace’s efforts to keep her children shielded from light.

Opponent

Grace’s main opponent is her own daughter who is beginning to enter the defiant years. She won’t do as her mother tells her to do. If Grace’s main desire is to keep her children hidden from the light (from the truth), Anne’s desire is to live, and to live authentically. She cannot ignore evidence of strange happenings, even if she isn’t fully cognisant of the truth.

Other opponents are the unseen living people who have moved into the house. Mainly, it’s the clairvoyant who has the power to get rid of them, and the main desire is to stay in the house.

Mystery

The mystery is: Whose version of the truth are we to believe — is Anne making stories up? What are those noises? Are they still surrounded? Are the noises real? Are they coming from anywhere at all, or is Mrs Mills playing some sort of psychological trick on Grace? Who is the victim here? What is Mrs Mills’ motivation? The mystery thickens when we learn that Mrs Mills has served in this house before. Why has she come back?

Fake-ally opponent

The returning husband almost fits this description: Does he know that he is dead? Is that why he took off, to heaven? It seems he has worked out the truth of ‘that day’ from Anne, and perhaps he feels bad for his wife but does not want to spend the rest of forever with her. He makes love to her and leaves. So during that scene I suppose he’s a fake-ally. Or perhaps his real life experiences on the battlefield have made more of an impression on him than his house, and so his permanent otherworld arena is the battlefield rather than one of domesticity. (In ghost lore, ghosts hang around places when they feel a strong connection to that place.)

Changed desire and motive

Grace’s desire doesn’t waver throughout this story — her only motivation is to keep the house dark.

Even when faced with evidence to the contrary, Grace turns back to the bible, refusing to believe in supernatural things. But she realises she’s going to have to get the priest in to help.

First revelation and decision

The first big reveal is that Anne has been telling the truth — there do seem to be ghosts in the house. We see a bit of emotional growth when Grace apologises to Anne. Grace realises this for herself when she locks the piano lid then goes back to find it open seconds later. Curtains are drawn when they shouldn’t be.

Plan

More bible lessons for the children.

Opponent’s plan and main counterattack

This is a waiting game. (As Roger Ebert wrote:It’s not a freak show but a waiting game, in which an atmosphere of dread slowly envelops the characters—too slowly.) Mrs Mills knows that eventually the other side will provide enough evidence to provide Grace with her revelation.

Drive

Grace realises the house is indeed haunted so she runs out into the fog to find the priest who will supposedly bless the house and fix everything. If my theory about the agoraphobia is right, it would take desperation for Grace to run out like this.

Attack by ally

Mrs Mills gently challenges Grace at various points by dropping hints about her being dead, but she as she tells Mr Tuttle, she must come to the realisation on her own, because she won’t accept being told the truth. This is part of the religious theme of the story; in some ways it seems to contradict the Roman Catholic teachings, but in other ways it has a religious message: You have to experience spirituality for yourself; you can’t really accept spiritual things simply by being told.

Apparent defeat

It seems Grace has lost everything when her daughter is defiant. Grace can’t control the lighting in her house, doesn’t know who the intruders are (suspects they’re war criminals) and even begins to suspect the house servants of wrongdoing. She has no one as an ally. She is especially defeated when her husband leaves for a second time. Could anything else be worse for this character?

Obsessive drive, changed drive, and motive

Grace is so obsessed with protecting her house and children that she takes out a gun. There’s a great scary moment when she is holding the gun and opens a door. (If you saw it in a theatre you may well have jumped!)

Second revelation and decision

Grace realises she needs to be a little softer on Anne. This comes after the scene in which she attacks her when dressed in her confirmation dress. Grace is starting to question her own sanity. She is able to say sorry to her daughter thinking her daughter is asleep. This is the very beginning of her new psychological state. The former Grace was not the sort of woman who could ever apologise to her own children.

Audience revelation

The audience is shown that there are gravestones in the yard, and that they are being covered by leaves. We’re likely to guess that the house servants are dead. (The graves look old, covered in moss.) Perhaps we know one party is dead, but we’re not sure who. (It all depends on how many ghost stories you have read.)

Third revelation and decision

I lose count of the various revelations, but this is the point where the hero usually works out the opponent’s true identity. I suppose the third revelation takes place in the seance scene. Surely Grace realises she’s the ghost right there. (These steps really need to be shuffled round a bit to be put into the correct order.)

Gate, gauntlet, visit to death

The removal of the curtains is the throwing down of the gauntlet. If sunlight means death to her children, it means a kind of death to Grace also.

Battle

Grace scares the house servants off the property with a gun, convinced that they are playing mind games with her. They’re not surprised that the curtains have gone missing, so she suspects them of taking them down.

Grace realises the servants are ghosts when she is finds the book of the dead (which of course has come up earlier in the film — Grace asked for it to be removed from the house). This is a wonderful prop to use in film because it’s so visual. If this were a novel, such a visual revelation probably wouldn’t be quite so necessary. The servants turn up again after the children have made the same discovery via their grave stones. The ghost servants tell Grace she had better go and talk to ‘them’. (On the other side, the new owners of the house are holding a seance.) Grace is furious about this and creates a bit of a poltergeist scene.

Calling the Spirits: A History of Seances

From Halloween expert Lisa Morton, bring us Calling the Spirits: A History of Seances (Reaktion, 2022), a level-headed and entertaining history of our desire and attempts to hold conversations with the dead. Calling the Spirits investigates the eerie history of our conversations with the dead, from necromancy in Homer’s Odyssey to the emergence of Spiritualism—when Victorians were entranced by mediums and the seance was born. Among our cast are the Fox sisters, teenagers surrounded by “spirit rappings”; Daniel Dunglas Home, the “greatest medium of all time”; Houdini and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, whose unlikely friendship was forged, then riven, by the afterlife; and Helen Duncan, the medium whose trial in 1944 for witchcraft proved more popular to the public than news about the war. The book also considers Ouija boards, modern psychics, and paranormal investigations, and is illustrated with engravings, fine art (from beyond), and photographs. Hugely entertaining, it begs the question: is anybody there . . . ?

New Books Network

Anagnorisis

It’s only when she’s huddling with her children after this battle that the events of ‘that day’ come back to her and she realises she, too, is dead. It is at this point the audience may remember how the story opened — with Grace screaming and then sitting up in bed. What had caused that scream? Now we know.

Moral decision

Now that Grace has ‘experienced’ spirituality she probably won’t stick so rigidly to the bible, and we can believe she’s not going to continue to bring her children up in strict, Victorian fashion. Now that she has had several anagnorises she will probably be a different kind of mother. (Though the past is the best predictor of the future…)

New situation

The family now has the house to themselves, though Mrs Mills says others will come — sometimes they’ll feel them, other times they won’t.

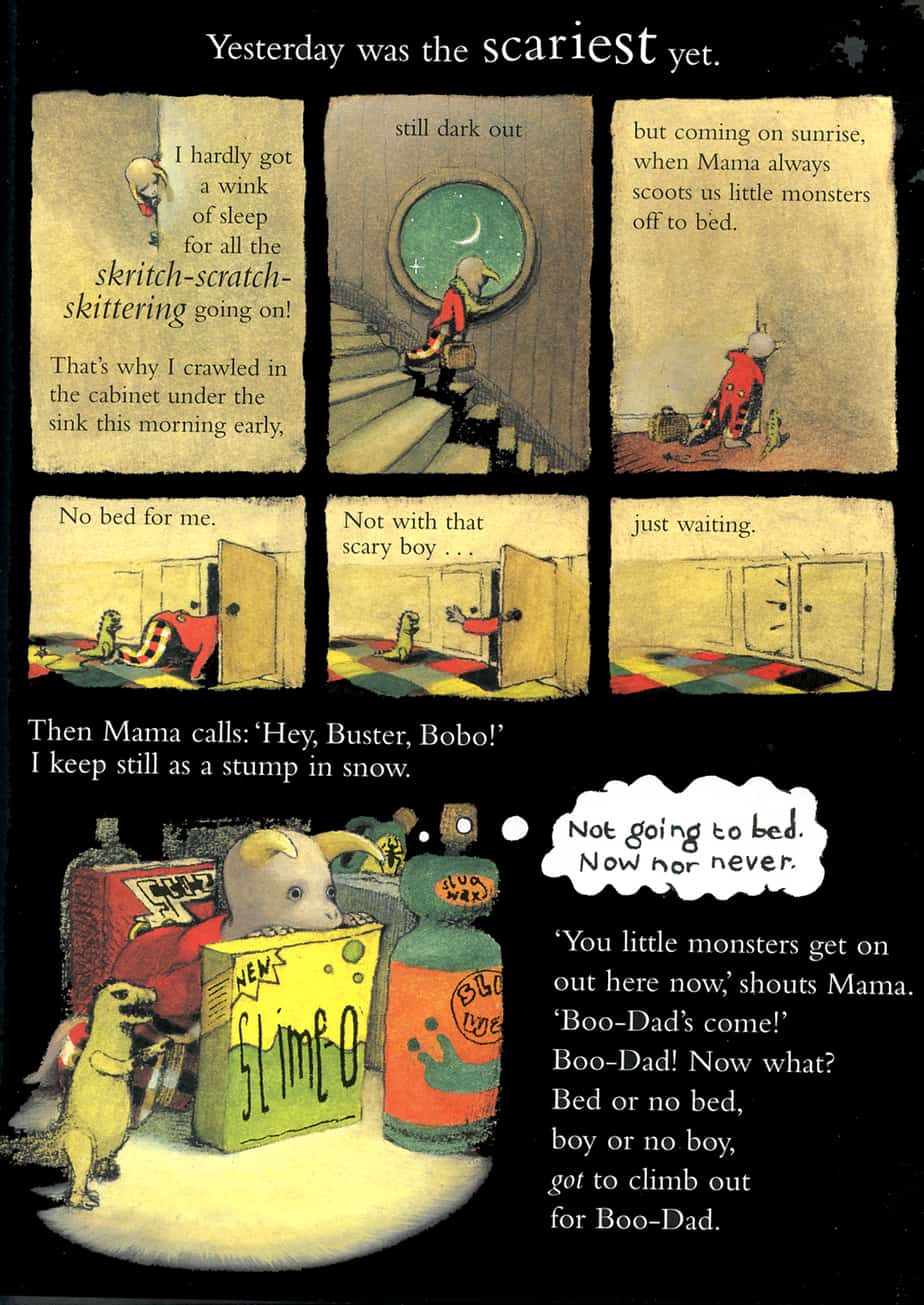

Creators of picture books also utilised this trope, most often by creating a creature who roams around at night but is adorable.