Hayao Miyazaki’s Ponyo is a feature-length anime which makes heavy use of myth and symbolism but is aimed squarely at a young child audience.

Gake no ue no Ponyo is the Japanese title: Ponyo At The Top Of The Cliff.

Dani Cavallaro, in Magic as Metaphor in Anime: A Critical Study describes Ponyo as ‘an intimate bildungsroman‘ and writes:

Sousuke’s developmental journey begins with his rescue of a plucky little goldfish that has run away from her underwater home and is desperately keen on becoming human (presumably unaware that such a status is by no means unproblematically advantageous), whom the boy calls Ponyo, vowing to protect her at any price. At the same time, the anime’s intimate mood is reinforced by its close focus on domestic life and the little boy’s relationship by its close focus on domestic life and the little boy’s relationship with his mother Lisa. The bildungsroman dramatized in Ponyo concentrates concurrently on two interrelated journeys. One of these addresses the human protagonist’s emotional and intellectual development as he negotiates the various complications attendant on his relationships not only with the heroine and the marine domain she comes from but also his caring mother and often absent father. The other focuses on Ponyo’s evolution from the moment she decides to abandon her father’s protected abode and explore the outside world with all its unforeseeable wonders and perils.

SETTING OF PONYO

Food

Food usually has its own starring role in the setting of Miyazaki movies.

- The feast that turns the parents into pigs in Spirited Away, then the steamed red bean buns and the sponge cake scene

- The bacon and eggs in Howl’s Moving Castle

- Herring pot pie and rice porridge (おかゆ) as well as all the fresh bread products from Kiki’s Delivery Service

- More rice porridge in Princess Mononoke

- Bento boxes from My Neighbour Totoro

- The fried egg in bread (目玉焼きパン) and the winter vegetable stew (煮物) from Laputa

- Fried horse mackerel (アジフライ) from Up On Poppy Hill (nothing to do with horses — it’s a different kind of mackerel)

In Ponyo we have the bowl of ramen (Chinese noodles)

The transmogrifying magic of food is repeated from Spirited Away in this film, in which by eating food from a different world, you become of that world — a literal interpretation of ‘You are what you eat’. It’s by licking the blood from Sousuke’s thumb that Ponyo is able to become human, but the huge hunk of ham seems to seal the deal.

Symbolism of the Cliff

This comes off a dodgy-looking dream symbolism site, but I think it does apply to a lot of literature, and to this film as well:

To be at the edge of a cliff is to be where earth meets both sea and sky. Sky is a symbol of consciousness/masculinity; sea is the unconscious/femininity.

I think there’s something in the masculine/feminine associations — Miyazaki has definitely made use of the dichotomy by making Sousuke a boy and Ponyo a girl. But as soon as Sousuke meets Ponyo, his feminine, caring side has a chance to shine:

Don’t worry, Ponyo. No matter what, I will protect you. I promise. I will love you too!

It is significant that this house is on a ‘cliff’ rather than on a mountain. The mountain in storytelling has quite different associations for the audience: The mountain is set in opposition to the plain. The mountain is where revelations happen (a la Moses), and in films, main characters often go to a high place in order to really work out what’s going on. The mountain is where revelations happen.

The cliff, on the other hand, is precarious. There is no safety to be had on top of a cliff. This house is elevated because its occupants are separate from the ocean, but when Ponyo arrives she unites land and ocean, and the ocean literally rises to engulf the house.

Symbolism of the Wind

Traditionally, a wind storm means that change is afoot. Something bad is about to happen — probably destruction or desolation. A precarious-looking house on a cliff is in particular danger.

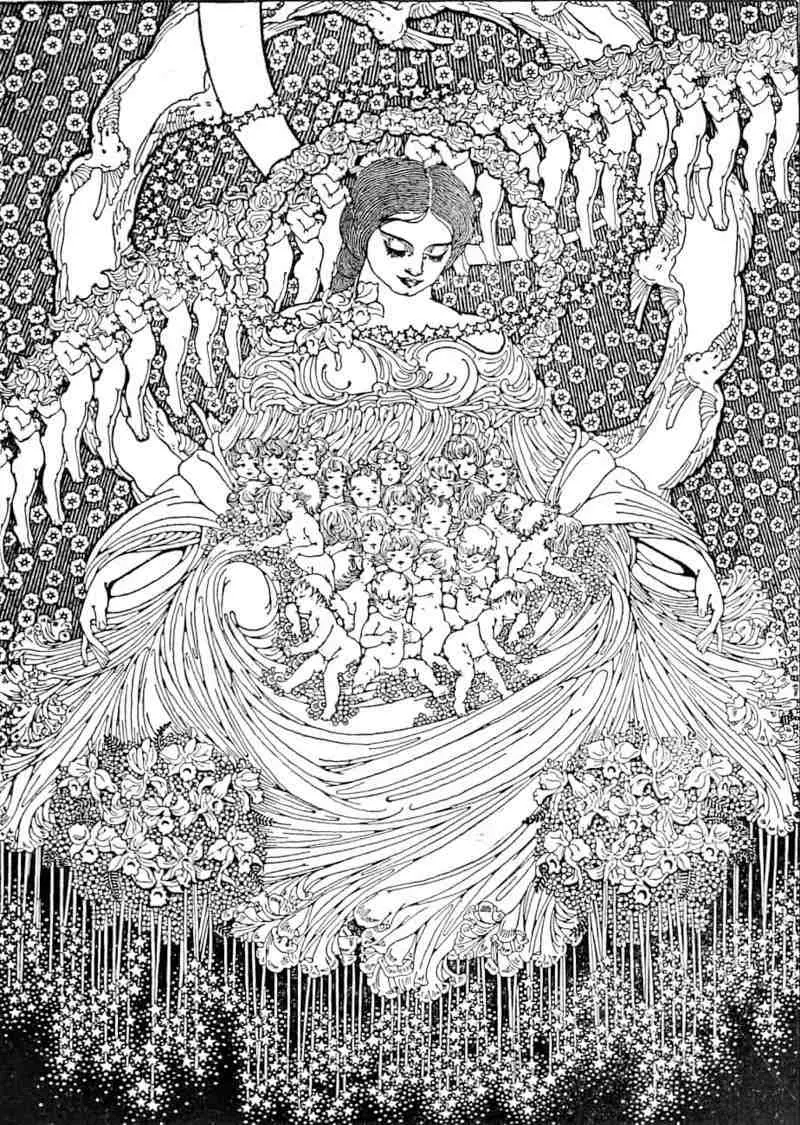

Chimeras in SF

Throughout history, hybrid creatures have functioned as remarkably versatile vehicles for the expression of abiding cultural anxieties. On many occasions, they have been rendered just about tolerable by the sublimation of their uncanny anatomies into so-called “curiosities.” Yet, this has frequently led to a paradoxical situation, insofar as our attraction to those beings’ intractable alterity is never conclusively anesthetized: much as we may seek to domesticate the threatening connotations they are held to carry, by relegating them to the province of the abnormal or the repulsive, the sense of menace abides as a vital component of their bizarre, monstrous and fearful beauty. In other words, hybrids’ attractiveness is inextricable from their intimidating power.

Dani Cavallaro, Magic as Metaphor in Anime: A Critical Study

Examples of hybrids in well-known tales:

- angels

- centaurs — a mythological creature with the upper body of a human and the lower body of a horse

- devils

- sphinxes — a mythical creature with, as a minimum, the head of a human and the body of a lion.

- termagants — In medieval Europe, Termagant was the name given to a god which Christians wrongly believed Muslims worshipped, represented in the mystery plays as a violent overbearing personage. The word is also used in modern English to mean a violent, overbearing, turbulent, brawling, quarrelsome woman; a virago, shrew, vixen.

- tritons — a mythological Greek god, the messenger of the sea. He is the son of Poseidon and Amphitrite, god and goddess of the sea respectively, and is herald for his father. He is usually represented as a merman, having the upper body of a human and the tail of a fish, “sea-hued”, according to Ovid “his shoulders barnacled with sea-shells”.

The spectrum of hybrid creatures can be beautiful, with lovely wings, or they can be monstrous and deformed, evoking a wide range of moods. Ponyo is strange in a jellyfish kind of way, but she is on the loveable part of the spectrum.

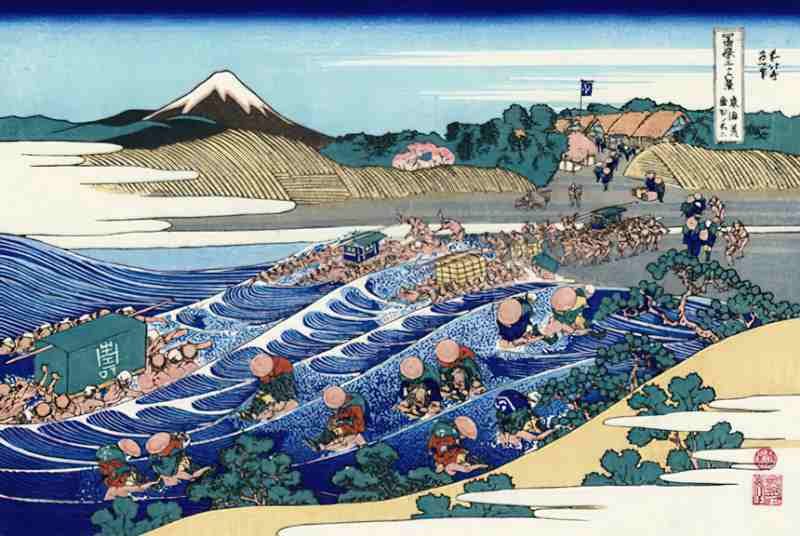

Miyazaki seems to have been influenced by traditional Japanese art in his depiction of water.

Roy Stafford makes some direct comparisons between this particular work and the film Ponyo:

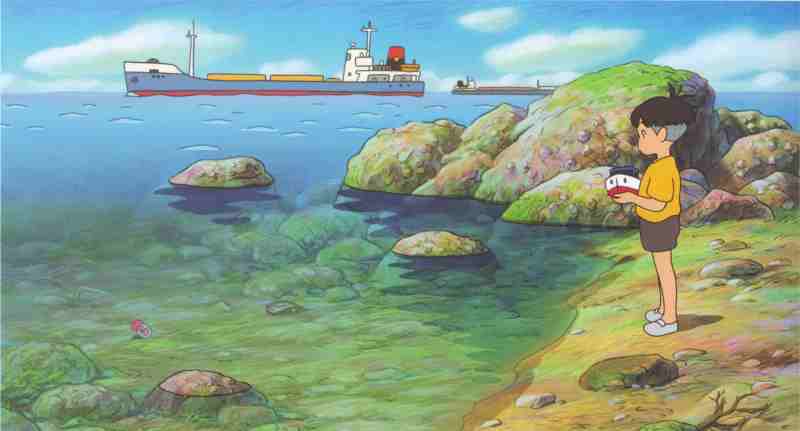

The triangle formed by the cliff-top house where Sosuke and his mother live, the ship at sea carrying the boy’s father and the school/old people’s centre is the centre of the world Miyazaki has created. It neatly represents the social concerns about an ageing population, an economy that still needs the resources of the seas and that perennial fascination for Miyazaki, the self-reliant children, seemingly confident because there is a community of supportive adults who are there when needed. Jonathan Ross, in one of his more lucid comments on Film Night, made the perceptive comment that in Ponyo, Miyazaki (writer and director) spends time on everyday incidents involving children and adults – such as sharing a cup of soup – in which this sense of a community of all ages, not just parents and their own children, comes across so forcefully.

The water is literally alive in this story, with the waves morphing back and forth between fish and water.

Here we have still waters, so the viewer can see the house on the cliff mirrored in the ocean. The water has risen and now the house — formally up high and therefore separated from the sea — is literally at one with it.

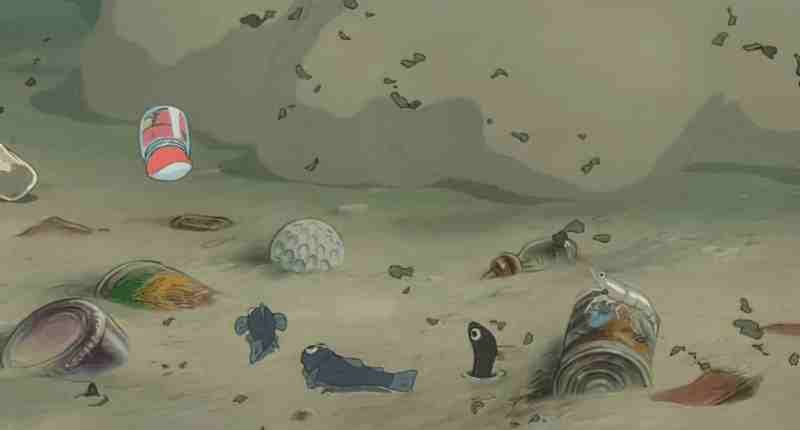

Miyazaki’s preoccupation with environmental issues, a crucial aspect of both his political perspective and his cinematic signature, obliquely permeates the marine habitat depicted in the film even though the recurrent images of dolphins and whales swimming about unmolested bear scarce resemblance to the reality of Japan’s notorious fishing ventures. […] Miyzaki also creates a tsunami that, however fantastical and benign he portrays it, can’t help recall the fatal force of nature.

Dani Cavallaro, Magic as Metaphor in Anime: A Critical Study

Ponyo’s Name

Although Ponyo’s real name is Brunhilde, Sousuke names her ‘Ponyo’. Why? This name is interesting in the context of Japanese onomatopoeia. Onomatopoeia and mimesis are a huge part of everyday Japanese, and if you are a fan of manga you’ll see onomatopoeic words used to their fullest in that genre. Miyazaki himself started in manga and is a native Japanese speaker, so it’s fair to conclude that he is also an expert in onomatopoeia.

The sound ‘pon’ in Japanese has a ‘burst’-like quality to it. ‘Pon-pon’ expresses the following sounds in Japanese (from 日英擬音擬態語活用辞典):

- The resounding sound or action of clapping one’s hands or beating a drum etc. continuously. [The repetition of the pon sound indicates the repetition.] It can also be used to describe the sound of an explosion or something bursting. [Ponyo ‘bursts’ into Sousuke’s life — she exists inside a bubble — another thing closely associated with ‘bursting’ in the world of a child.]

- Things being vigorously or carelessly said or done. [Related to Ponyo’s exuberant nature]

- To fill something to the brim. Also to fill something so full that it appears as though it could burst at any moment. [Related to the theme of being inundated by water/flood/environmental disaster].

Symbolism of the Tunnel

Tunnels are a classic symbol in fairy tales marking the ‘portal‘ between childhood and self-discovery (maturity).

But what does the tunnel mean in this story? Halfway through, the children get scared and turn back. The dark of the tunnel is at least ominous, if not a metaphor for death.

CHARACTERISATION

Ponyo As Mirror Image Of Sousuke

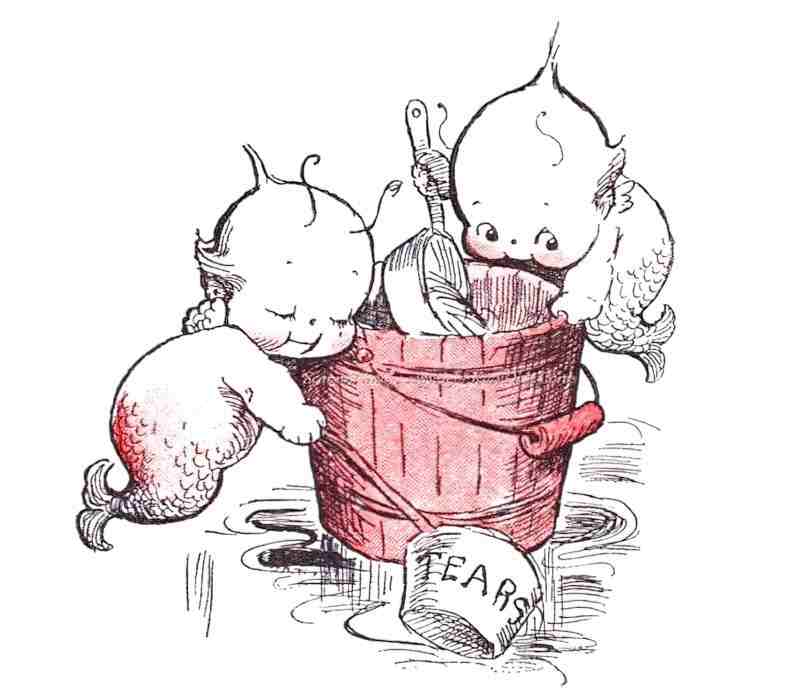

When Sousuke sees the ‘goldfish’ in the bucket, he sees the sea version of himself.

Using the red-oni, blue-oni trope (also used in The Girl Who Leapt Through Time), Miyazaki includes many frames in which these characters are basically mirror images of each other. In this shot, even the arrangement of the food inside the bowl is exactly the same. Ponyo is the more gregarious version of Sousuke, who actually comes from the sea rather than being fascinated by it. It’s natural that Sousuke is fascinated by the sea — it’s where his father works, and due to his father’s frequent absence, Sousuke would be glamorising the sea life.

Here’s another mirror image. While Sousuke’s interest is symbolised by the toy boat, Ponyo is more interested in the trappings of human life, symbolised by the lamp.

Sousuke’s Name

宗介 pronounced soo-suke

The individual characters mean centre/pillar/principle + mediate/shellfish

I’ve always thought it weird that the character for mediate also happens to mean shellfish. Is Miyazaki using that here, since shellfish are associated with the sea, and Sousuke is the mediation between the sea and the land?

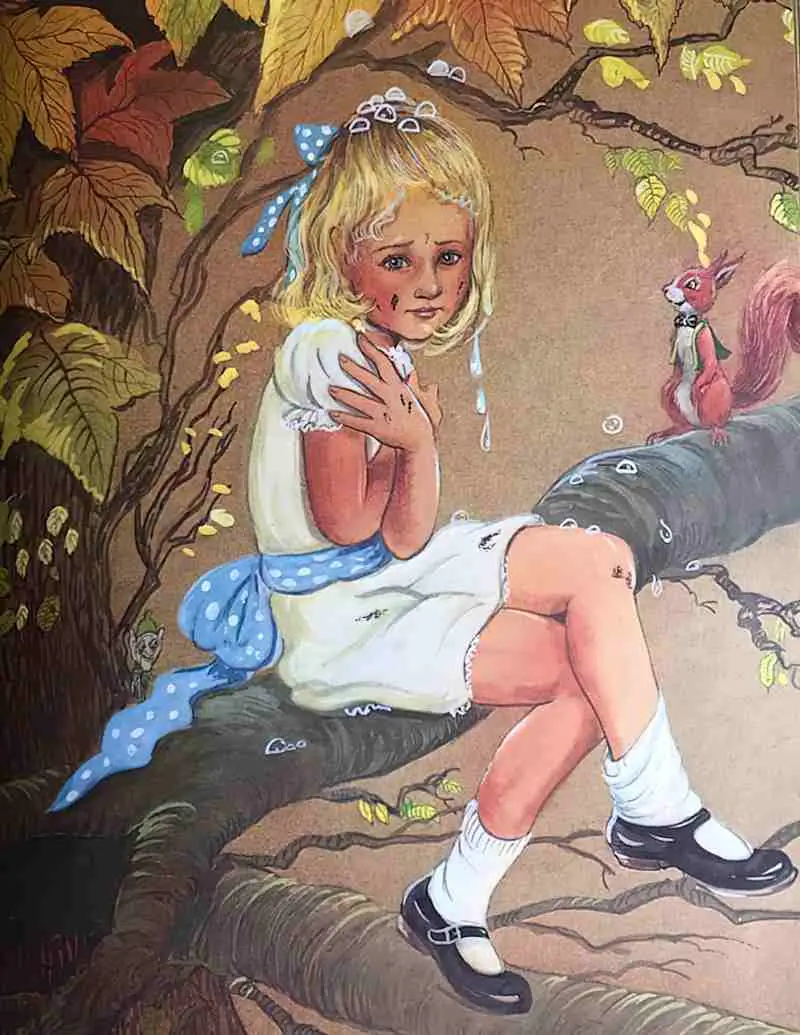

This gag reminds me very much of a scene featuring Connie from Enid Blyton’s The Folk of the Faraway Tree, the third in her Magic Faraway Tree series. In my illustrated deluxe version there is a picture of Connie that closely matches this one.

In Blyton’s story, too, a girl who is preoccupied with her appearance (pretty dresses) gets her ‘comeuppance’ by having water dropped on her, in this case by Dame Washalot. Often in children’s stories, when a girly girl goes along with the dominant cultural idea that she should be pretty, rather than rejecting it, she is punished and ends up a version of ugly as a didactic message. Miyazaki uses the same trope when he first shows the scene in which the little girl shows Sousuke her pretty new dress but then is later punished — ostensibly for calling Ponyo unappealing — by having water squirted in her face. (I could continue into adult territory and explore this popular metaphor further, but I don’t want that kind of traffic to my blog.)

Sousuke is therefore embracing the caring, nurturing side of femininity, but the filmmaker is also very obviously rejecting that other side of femininity, the one in which appearance is important. What does this mean for the story? Perhaps Miyazaki is saying that humans are inclined to ignore that which is just beneath the surface. In the case of the ocean, it still looks blue to us and unless we’re schooled otherwise, we have no idea about mercury poisoning and the imminent extinction of coral reefs.

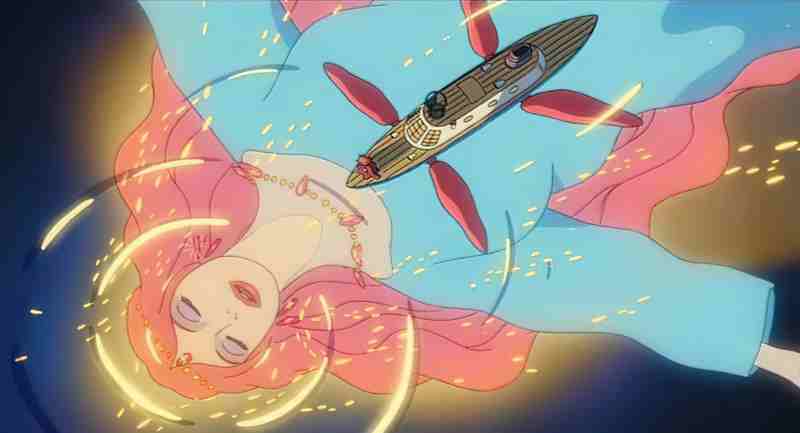

Granmamare

On the other hand, Ponyo’s mother is not only good but she is also beautiful. Her amazing beauty is conveyed mainly through her eyes. Whereas the other characters get simply drawn eyes, the Granmamare gets highly detailed, hyper-realistic eyes which not only serve to ‘other’ her — she is not of our world — but also serve to link goodness with beauty. I wonder if Miyazaki is conscious of this beauty of beauty in the very same story — beauty equals goodness when it comes to female characters, but when little girls aim for beauty, they are punished.

This view of Granmamare reminds me of the classic painting of Ophelia. This relaxed pose is in juxtaposition to the wild and frantic Risa, Sousuke’s mother.

Ophelia is a painting by British artist Sir John Everett Millais, completed between 1851 and 1852. It is held in the Tate Britain in London. It depicts Ophelia, a character from William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet, singing before she drowns in a river in Denmark.

Sousuke’s Mother

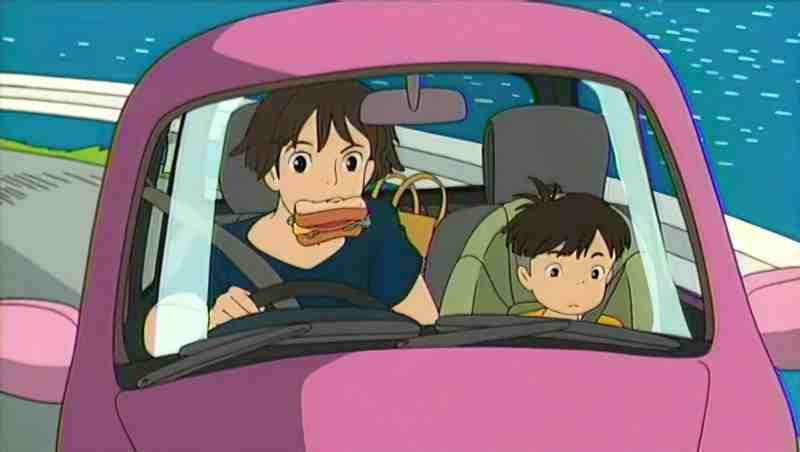

The mother in Ponyo is a bit of a departure for Miyazaki, whose fictional mothers tend to be devoted, 1950s housewife types. Perhaps we should be pleased that this mother is different — she is reckless to the point I would not get in a car with that woman. But the car is pink — is this a comment on woman drivers? Without the surrounding cultural trope I wouldn’t be thinking this at all, so let’s just put it aside.

There’s no doubt she’s gutsy — she ignores the special emergency services-type men who try to stop her driving the winding road back to her house on the cliff. She traverses a water-filled bridge while the tide is momentarily out and puts her own life and her son’s life at risk. For what?

The mother is like a human version of the wind that opens the movie. She is easily changeable, going from ecstatic that her husband will be coming home for the night to lolling about on the floor after drinking beer in a depression when he is required to work longer at sea. She’s not exactly your ‘strong, independent woman’ just because she works outside the house.

Risa is very much a part of the human world, oblivious to anything that might be happening under the sea, and doesn’t even think too hard about the wizard with the fertiliser back pack who says he’s just keeping himself wet. Her carnal nature is symbolised by her holding the ham sandwich in her maw, in most unladylike fashion.

Yet Sousuke’s mother is still very caring and maternal. She works in the Himawari (sunflower) old-folks’ home caring for the elderly and she cooks nice food for Sousuke. Conveniently for the plot, she is somewhat childlike herself, and doesn’t wonder too much about the strange fish girl who her son has befriended and brings home with him to live.

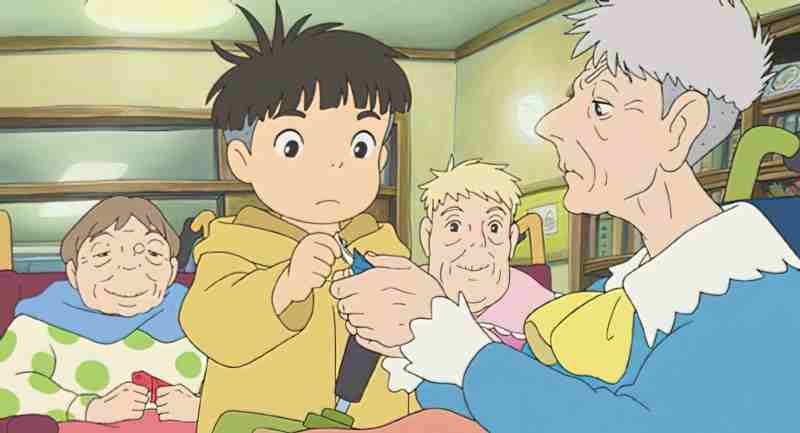

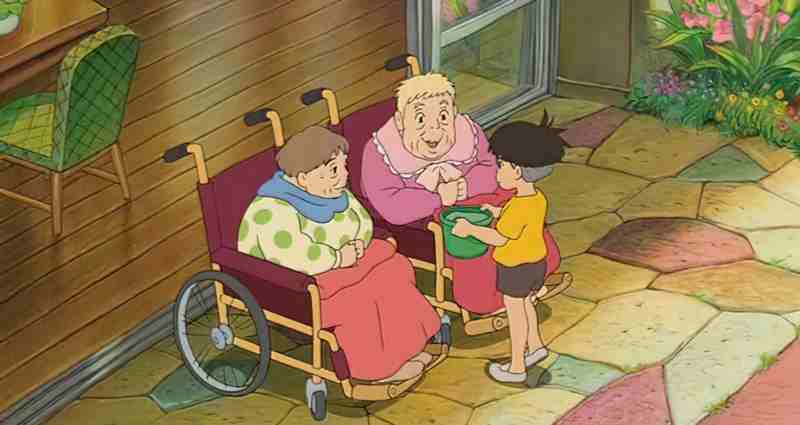

The Old Ladies

The old lady with the side shave didn’t know she was starting a trend, later emulated by Miley Cyrus and Rihanna. Sousuke has the same cut, which probably started as a good look for little boys to stop the headlice back in the day.

Significantly, the kindergarten is positioned right next to the old folks’ home: the young is juxtaposed with the old, or perhaps completes the ‘circle of life’ idea which is also conveyed via the earth/sea back and forth that happens throughout the plot. Old age is shown to be adjacent to childhood — in the scenes reminiscent of that 1985 movie Cocoon, the old women in wheelchairs can suddenly walk and run like they did as children when they are transported into the underwater playground.

In their wheelchairs, however, they are at the same head level as the five-year-old boy.

Menahem Kahana

Fujimoto

This guy from under the sea used to be a human so naturally he still has a human name.

Dani Cavallaro, in Magic as Metaphor in Anime: A Critical Study compares Fujimoto to parental figures in other Miyazaki films:

A lurking sense of menace redolent of the atmosphere prevalent in Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away and Howl’s Moving Castle emanates from the character of Fujimoto, Ponyo’s father. However, the forest kami [gods] depicted in Princess Mononoke are surrounded by an alarming aura even when their actions are charitable. Spirited Away’s bathhouse spirits are invariably invested with sinister iconographic connotations despite their often comical traits, and the mutants deployed as military machinery in Howl’s Moving Castle are even more explicitly baleful, lacking any concessions to humor in their alternately repugnant and horrific constitutions. Ponyo’s father, by contrast, comes across more as a solipsistic patriarch with a peculiar sense of fashion than as a consummate villain. Nor is he utterly devoid of benevolent intentions. A sorcerer intent on the concoction of life-giving elixir that could purge the mess humanity has unleashed into the ocean, Fujimoto is determined to confine his daughter to his watery lair. There is every chance that the wizard’s objection to his daughter’s desires has a lot to do with its stark contravention of the role model he has set. He indeed describes himself as an “ex-human” — a type ostensibly issuing from some sea-change intervention — and, like most fresh converts, is driven by the manic fervor of a zealot. Thus, Ponyo only echoes the epic scope of Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away and Howl’s Moving Castle insofar as Fujimoto’s efforts to restrain Ponyo evince the tone of a figurative mini-crusade.

While Fujimoto appears relatively harmless by comparison with either the malicious Yubaba or Howl’s warmongering despots, he is initially successful in tearing Ponyo away from her beloved Sousuke. If Sousuke, palpably heartbroken, is powerless to intervene, Miyazaki’s version of the Little Mermaid will stop at nothing to see her wish to be human and to live with her savior fulfilled. In the course of a fierce confrontation with Fujimoto, she rejects the name the sorcerer has imposed upon her, “Brunnhild,” and declares her name to be Ponyo (the allusion to Norse mythology is worth of notice).

With the help of her sisters, she then manages to flee the paternal prison once more and turns herself into a human by recourse to Fujimoto’s own magic. Regrettably, by releasing into the sea the wizard’s entire supply of elixir, Ponyo also triggers a massive environmental imbalance, which in turn causes the seas to boil, mammoth prehistoric fish from the Devonian era to invade the flooded land, the moon to stray outside its customary orbit and satellites to race across the sky like frantic shooting stars. In this respect, the movie stands out as a subtle parable about the precariousness of ecological equilibrium.

Magic as Metaphor in Anime: A Critical Study

FURTHER READING

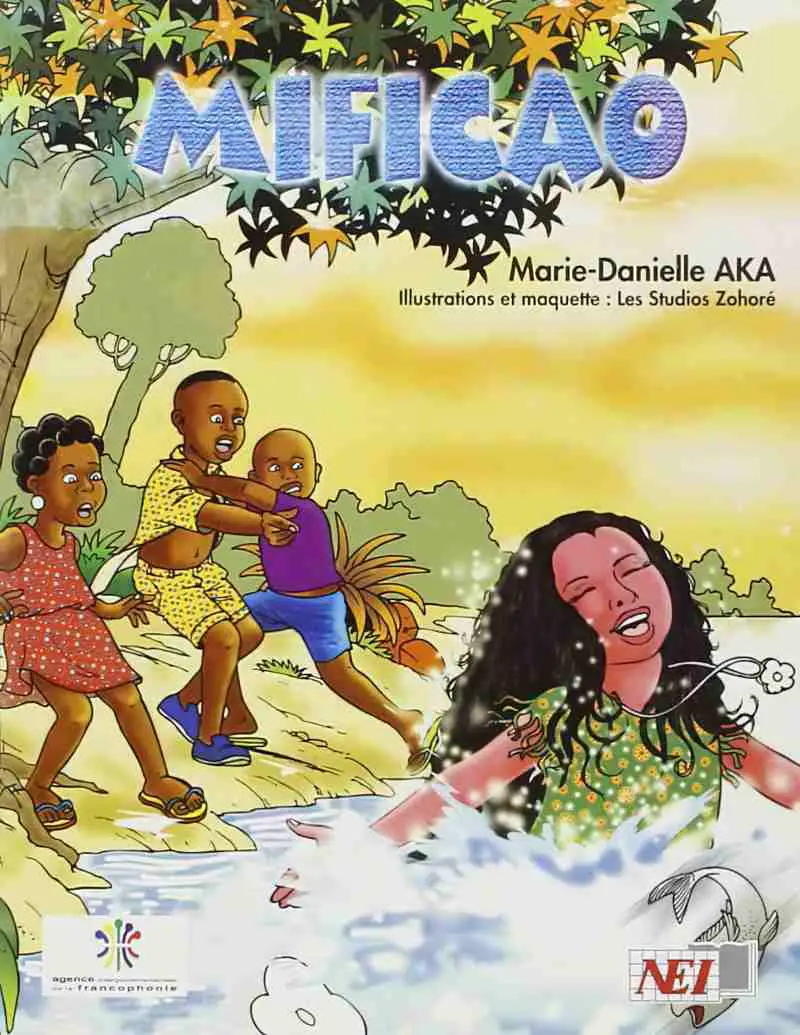

Mificao is a picture book from the Ivory Coast, by Marie-Danielle Aka, illustrated by Les Studios Zohoré. This story shares similarities to Ponyo:

Underwater, a little carp watches the village children play, and wants to join them. A good genie fish changes her into a little girl and there she is, Mificao, with her new friends Yaro and Ziza who guide her in her discovery of the daily life of the village. She also discovers garbage heaps, the technique of scorched earth… and gives lessons for better hygiene and the protection of nature. But can Mificao stay forever far from her own people?The text is long; colourful illustrations give a good idea of life in the village.

The World Through Picture Books

Cartoonist Liana Finck’s Let There Be Light” recasts the story of Genesis with a female God who is a neurotic artist. Finck has said in interview that she based the main character ‘a tiny bit on Ponyo’, a very powerful little girl who can work magic. At the beginning she exists in a void and just decides to make something. It’s all fun and games until she starts to feel self-doubt and realises she hasn’t done well enough. She’s well-intentioned, happy and hard on herself. She has a big ego, realises she has a big ego and then hates herself for it.