Me And Earl And The Dying Girl is a metafictive coming-of-age film based on a young adult novel by the same name. The book is an example of ‘sick-lit‘.

Greg […] is coasting through senior year of high school as anonymously as possible, avoiding social interactions like the plague while secretly making spirited, bizarre films with Earl, his only friend. But both his anonymity and friendship threaten to unravel when his mother forces him to befriend a classmate with leukemia.

Deadline Hollywood

Okay, I admit it. I thought, “This is very much like The Fault In Our Stars.”

But remember, the sick-lit genre popular in this Third Golden Age Of Children’s Literature did not actually start with John Green’s young adult novel — it started way back in the late 1990s with The Lovely Bones.

The young adult novel by Jesse Andrews Me and Earl and the Dying Girl was published in 2012 and released as a film three years later in 2015. Jesse Andrews was the main scriptwriter for that. Here I’ll be talking about the film because I haven’t read the book.

Apart from a breakdown of story structure, in this post I’d like to touch on:

- “sick-lit” — yes, it’s a derisive term but what else can I call it?

- the female maturity principle

- mothers in coming-of-age stories

- tear-jerkiness and how to achieve it

- the metafictive elements of this self-aware coming-of-age tale

TAGLINE OF ME AND EARL AND THE DYING GIRL

“A little friendship never killed anyone.”

GENRE BLEND OF ME AND EARL AND THE DYING GIRL

drama, comedy >> coming-of-age tearjerker

SENTENCE BEHIND THE STORY OF ME AND EARL AND THE DYING GIRL

I’m having trouble with this. Could it really be as simple as:

Sometimes it takes proximal death to teach us the value of life?

SETTING OF ME AND EARL AND THE DYING GIRL

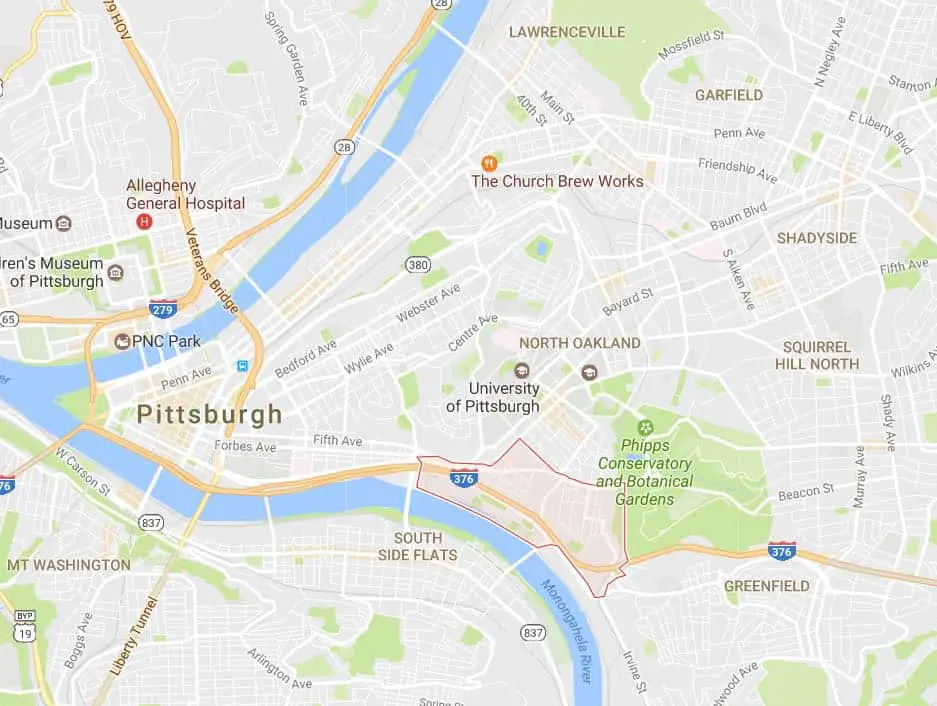

The author himself attended Schenley High School, Oakland, Pittsburgh, not that long ago (as of 2017 he’s only 34). The story is set there, and suburban surrounds.

The majority of the film adaptation was actually taped at Schenley High School. When the cameras showed us the corridors from above I noticed that the tops of the lockers were dusty and the place had a general run-down look to it compared to slightly more glossy depictions of high schools in other teen dramas coming out of America. As it turns out, this may not have been because the set designers were actively aiming for a run-down state school — the real Schenley High School closed its doors back in 2008 after 99 years. This was originally an expensive school to build — one of the first to cost a million dollars, which was a lot back then. In 2013 the historic but closed school was sold to some developers who plan to turn it into luxury apartments. Anyhow, the filmmakers must have scooted in there before that happened.

In short, this setting is not some anonymous mid-western place, or a fictional high school set in a real town — this is a very real setting and locals of Oakland can no doubt recognise the landmarks, especially the Children’s Hospital.

Greg lives in a large, warm house, indicated by its highly decorative wallpaper and yellow hue.

Rachel lives in a similar kind of house with a bedroom that looks like it was probably set up by an interior designer. A feature of Rachel’s bedroom is that there are lots of scissors hung decoratively above her desk. I thought this was a cool idea (because first of all it would be hard to lose every pair of scissors in the damn house) but it was actually a Chekhov’s gun — later it is revealed with Rachel would have been using those scissors for (book carvings). In fact the art of intricate book carving as depicted in the film requires more than just a bunch of big scissors, but the scissors are — of course — symbolic in other ways.

STORY STRUCTURE OF ME AND EARL AND THE DYING GIRL

In a very similar technique to that used in The Edge Of Seventeen we have a storyteller narrator taking us through the story, popping in at various point. The storyteller is the main character and their voices haven’t aged, suggesting they are telling the whole story pretty soon after the whole thing happened. The narrators are still young, still relatable to a young audience, and despite going through the harrowing events as described in the story, are still sufficiently flawed for us to find the storytellers interesting in their own right. (I’m treating the character and the storyteller as different entities because one has been through the character arc while the other is yet to.)

SHORTCOMING

If you ever meet a white middle-class called Greg in a story he’s probably going to be an Average Guy. We’ve got Greg Heffley in Diary of a Wimpy Kid, for instance. (If he’s called Gregory plus a weird last name, my rule of thumb doesn’t work.) Dan is another name like that. The audience is encouraged to look past common male names like that and see the person underneath. These names have no character and no symbolic value.

Anyway, Greg in this particular story is so ordinary he is ridiculously self-effacing, to the point where he doesn’t see the point in anything, including in applying for college. You may know a few of these boys in real life. If not (and you’re at this blog), you’ll have met them in YA, for sure. Think slightly more more self-effacing than a John Green boy. I’d liken Greg’s feeling of hopelessness to James Sveck of Someday This Pain Will Be Useful To You (who also happens to have depression), or to Joe of Kings Of Summer.

Of all the fictional characters I’ve ever met, Greg reminds me most of Josh Thomas’ character based on himself (Josh) of the Australian sit-com Please Like Me. They even kind of look similar.

Whereas Greg says things like this:

You know I’m terminally awkward and I have a face like a little groundhog.

Josh says he has the body of a woman and the face of an old man. Both characters are reactive rather than proactive — the classic witty underdog. The audience feels for them though because even if other characters in the setting do not laugh at his jokes, the audience finds them funny. We learn to see the underdog as the true wit — what’s wrong with these other characters?

Summer. What does that word even mean, right? More “summ.” Winter, same deal. More “wint”?

Greg, Me and Earl and the Dying Girl

Both Greg and Josh are close to a female with an illness — in this case it’s the daughter of his friend’s mum who has leukemia; in Josh’s case it’s his on-screen mum with depression. Josh Thomas has been praised for bringing awareness to mental illness here in Australia.

Do you have to be under a certain age to find these characters appealing? I haven’t done a wide enough survey. Speaking for myself, I find these characters fine for a short time and then they get irritatingly self-absorbed.

In Greg we have a guy who has actually found his passion — and what else can a teenager hope for? — but is so negative he doesn’t realise he’s found it already:

The idea behind each one was we took a film that we like and made the title stupider. And then made a new film to reflect the new stupid title. It’s a formula that only produces horrible films, but for some reason we kept using it.

DESIRE

Writers are told time and again: Your character has to want something!! If your character just sits around moping no one wants to read your shit!

But but but in real life there are definitely people who sit around moping and reacting to stuff and don’t their stories need to be told too? I mean, doesn’t that describe A LOT of teenagers you know? It may have even described you as a teen, and don’t you deserve to see yourself reflected in fiction?

As this story makes clear, a writer can absolutely make a story about a mopey guy who doesn’t really want anything. (I don’t know quite as many mopey girls who don’t want anything, but I’m on the look out.) Me and Earl and the Dying Girl is obviously a very popular story, too. The book has won awards. But there is a trick that must be utilised if you want to write about a generally depressive, nihilist, unmotivated character:

You know that trick when you’re writing an unlikeable character where you surround that character in other characters who obviously do like them? Well, same trick applies here. If your main character doesn’t want anything, surround him in people who do want things. They will force him into things. These characters are by definition his opponents — not in the criminal/evil/monster sense, but they’re probably going to be members of his family or in his wider social sphere.

What does Greg’s mother want? She wants him to be a good human being. Her way of going about this is a little misguided, but ultimately successful, let’s face it. She also wants him to apply for college.

What does Rachel’s girl friend Madison want? She wants Greg to do something amazing for Rachel by making her a short film.

OPPONENT

And of course anyone who wants Greg to do anything at all is his opponent. It’s tempting to cut this paragraph short by saying “Greg is his own worst enemy.” That’s true enough, and would be absolutely true in real life, but for the sake of a story we need a few human opponents otherwise you haven’t got enough to beef out a complete narrative.

In this particular story we have the mother spurring her son into action. She makes him go spend time with Rachel even though he (quite rightly) thinks it would be weird to suddenly strike up a friendship with someone just because she’s dying. Once this is in action and the mother steps out of the story we have another maternal figure pop in: Rachel’s pretty friend who insists Greg make a movie for Rachel. We see her again when she’s swearing at him, asking why he hasn’t finished it yet. This provides Greg’s motivation for the second part of the story, which would otherwise flag as he sits around thinking his film is too terrible to show anyone.

On this topic, the need for teenagers in non-fantasy stories to have an opponent means that, inevitably, parents end up filling that role. I feel mothers (and female teachers) get an unbalanced share of the ‘annoying adult’ roles. It was disappointing to see actor Connie Britton wasted in this way — I’ve recently seen her in Nashville in which she is a fully-rounded character with a wide acting range, but here she is nothing but a neurotic nag who has even been going through her son’s stuff. TV fathers rarely get that role, unless there is good reason to suspect his kid is on drugs or something, but the overbearing mother who goes through her teenager’s things for no good reason? A common trope. Notice that once the mother’s power to boss Greg around wore off, it was another female figure who stepped in to boss him around. This is a version of what I call The Female Maturity Formula, in which all girls are Mothers-In-Waiting, naturally more caring and nurturing (and concomitantly annoying), in opposition to their male stars-of-the-show, who must go through something harrowing before starting to grow up.

This is not the problem of any individual story but applies to the corpus of popular stories. Mothers are generally a damn nuisance in coming-of-age stories. It is very rare for a teenager to have an excellent mother. Juno (2007) is one exception — not only that, Juno has a great step-mother. But then Juno is more of a bildungsroman than a coming-of-age story. Her goal isn’t ‘to have sex’ or ‘get the guy’ — she’s already done that after the first five minutes of the movie.

The character of Rachel, although this is not a love story, is written very similarly to any love opponent in a typical love story. When we first see them together on screen there is conflict:

Rachel: Is that a black power salute?

Greg: No, I was going in for a fist bump.

Rachel: I can’t fist bump you from up here.

Greg: Yeah, I realize that.

I’m not saying much about Earl in this story breakdown even though he gets quite a lot of screentime. That’s because there’s not all that much to say about him. He is the funny character who provides comedy. Apart from that, he plays one main role — he is the ally who attacks Greg for his wrong choices. You’ll find someone to fulfil this role in almost every popular story:

I’m so tired of you treating this girl like she’s a burden. You know, her life is over after this! And you want to come over here bitching and whining about some irrelevant bullshit!

In this self-aware coming-of-age story the character of Earl is also wise beyond his years, and his understanding of Greg is comical because this is the kind of character analysis we’re only supposed to achieve after the entire story is over and we’re writing an English assignment on it:

Rachel: So you and Greg are coworkers?

Earl: Naw, we just friends. He just hates calling people his friend. Dude’s got issues.

Rachel: Yeah, he does. What’s going on?

Earl: Man, I don’t even know. It might be his folks. I mean, dude’s mom always tellin’ him how handsome he is, which he ain’t. So now he think he can’t trust anybody close to him. Dude’s weird-ass dad don’t socialize with anybody ‘cept the cat. So that’s a role model ain’t got no friends. Bottom line, dude’s terrified of callin’ somebody his friend…

PLAN

Greg’s plan: Hang out with Rachel and make her laugh as much as possible. Also, she is a reason for him not to do any schoolwork whatsoever. So on one level he must have planned not to do any of that.

As mentioned above, Greg’s concrete plans-of-action come from the women around him.

BIG STRUGGLE

Greg has arguments with everyone in their turn.

He has an argument with Earl, who tells him not to be so self-absorbed.

He has an argument with Rachel, who he first fails to cheer up one day and then when she eventually does crack a joke he gets the shits with her because she’s meant to be sad about dying (and besides, he’s the funny man, not her).

Obviously I have a few issues with the character of Greg, and these are correctly anticipated by the author, who has straight-talking Earl tell Greg exactly what I’d like to tell him myself:

Earl: Like you care so much about what other people think, boy, you go around here kissing everybody’s ass pretending like they’re your friend. Look, nobody gives a shit about you, Greg! All right? Nobody gives a shit.

This goes quite a long way towards making the character of Greg bearable for me.

But is this series of arguments the real big struggle, narratively speaking? Actually no. I’ve analysed enough stories now to know that these interpersonal conflicts need to add up to something big. A fight to the death.

The real big struggle scene of this story, therefore, is the bit where Greg blows off the prom to visit Rachel in hospital. He takes her flowers, shows her the film against the white of the hospital wall and she dies then and there. The film-within-a-film itself is the big struggle, in storytelling terms.

ANAGNORISIS

Greg mulls over Rachel’s death. We see him hang out in her room, going through her stuff. He (and we) realise that Rachel had hidden depths at this point. Although she’s ‘The Dying Girl’ in the title, and the boys get their own names, finally we get to see Rachel for more than just The Dying Girl. For instance, she loved to make those book sculptures, demonstrating a high degree of artistry. She has a quirky sense of humour evidenced by the drawings of squirrels on her wallpaper. She is more like Greg than Greg realised. I rather cynically thought if only he’d stopped trying to crack jokes for five minutes and listen to her he could’ve realised that in real life. I’m not sure how common this response is to the denouement.

Another revelation is that Rachel had probably been waiting for Greg’s film before dying. That’s the narratively convenient thing about cancer — a character (and also a person in real life) can hold on for a big event before moving on. Heart attacks, strokes and accidents, in fiction as in real life, do not allow for that. This is probably why cancer is gaining a reputation for being an overly romanticised fictional way to die.

NEW SITUATION

When we see Greg going ahead with his college application we realise he’s going to (re)apply to get in even though he doesn’t have the grades for it. Once again, a female character has been responsible for his pulling finger. She’s even composed a letter to the enrolment office on his behalf, and encourages him to do the same from beyond the grave.

We never learn whether Greg gets into college or not.

Are we supposed to believe that he is transformed by the death of someone he got close to? That he will take his own life by the reins from now on? A cynical audience may see that nothing Greg has done yet has been without the help of a female — dead or alive — and unless he goes through life relying on women to do his emotional labour, he may well die unfulfilled and alone. Fortunately for him, Greg is smart, good at making films and has a self-deprecating sense of humour. I’m left in no doubt: He will find the right girl (or a series of them, until he wears them out) and he will do just fine. He’s also white and middle-class so I’m sure he gets into college somehow.

TEAR-JERKINESS AND HOW TO ACHIEVE IT

I find it hard to believe that these tricks work for so many people because they don’t work for me. This may be because I am cold and heartless, or because I’ve seen it done a few too many times before, but if you want to leave your audience in floods of tears there are a few things you can do to help that along:

- The person who dies is young and good-looking and likeable

- The dying character has been waiting for something significant/quirky and doesn’t die until right after that has come to fruition

- The main character rejects a significant life event (or portion of life) to sacrifice time for the dying character

- There are arguments before the moment of death to do with selfishness, optimism, acceptance and hopelessness

- The main character finds the dead character had hidden depths, but not until after she is gone

- The dead character has put something in place before she died, to ‘come back from the grave’. The book offers her letter to the admissions board; the film even has her voiceover, which is kind of similar to hearing someone’s answering service after they’ve died. Terribly sad and a little bit spooky.

- Flashbacks to when the dead character looked healthy and plump and pretty

Dear Pittsburgh State Admissions, I’m writing on behalf of someone who gave me half a year of his life at the time when I was at my most difficult to be around. He has a very low opinion of himself, which is why I think it’s necessary that you hear from someone who sees him as he actually is: A limitlessly kind, sweet, giving, and genuine person. No matter how much he would deny it. The drop in his academic performance this year is the consequence of all the time he spent with me and the time he spent making things for me and how hard that was for him. You can ask him about it, but his sort of over the top humility will probably get in the way. No one has done more to make me smile than he has. And no one ever could.

Rachel’s letter from beyond the grave

This particular story goes one step further, and I personally find it overly manipulative: The storyteller’s insistence that The Girl Doesn’t Die. Greg’s voiceover reassures us of this several times over the course of the story. This despite him initially telling us that in his senior year he killed a girl. This is a red herring, and because the only other main girl in the story is Madison, and because she’s basically bossy and unlikeable I was wondering if something would happen to her the night of the prom, without Greg there to protect her or whatever. But no. Nothing happens to Madison; Rachel dies and Greg’s voiceover tells us he lied. Reason being, he didn’t want to believe it himself.

This revelation is meant to punch you in the guts. I’m sure it worked for a goodly proportion of the audience, too. Narratively, the audience is walking in Greg’s shoes. Greg at no point believes Rachel is going to die, so he puts the audience through the same journey. That’s the explanation, anyway.

SELF-AWARE METAFICTIVE COMING-OF-AGE STORY

The film-maker part of Greg (and the author who created him) is aware of popular narrative, especially the subgenre of the coming-of-age story. Greg mocks this in a hipster fashion (which, come to think of it, makes me think he would’ve got into film school):

Generally in a coming-of-age story there is a hot girl who you destroy your life over. This is done in straight fashion in Kings Of Summer and many others:

One last thing. Hot girls destroy your life. That’s just a fact.

Greg says this at the moment Rachel starts to warm to him:

So if this was a touching romantic story this is probably where a new feeling would wash over me and suddenly we would be furiously making out with the fire of a thousand suns. But this isn’t a touching romantic story.

Despite Greg telling the audience that this is not a romantic story, it is nonetheless a love story. I would love to know if the audience is meant to believe this is something else, a bit like Nicholas Sparks writing chick-lit then cracking on he’s actually writing ‘love tragedy’, or if we’re meant to laugh at Greg thinking this is not a romance when it so obviously is. Or perhaps the author truly intends to test the audience when he has Greg say:

So again, if this was a touching, romantic story we’d obviously fall in love and she’d say all the wise, beautiful things that can only be learned in life’s twilight or whatever. And then she’d die in my arms. But again, that’s not what happened. She just got quieter and unhappier.

The writer demonstrates a strong sense of narrative structure by using a metafictive technique of subtitling the bits when the story changes direction. This is usually something only the writers/screenwriters are cognizant of. The audience isn’t usually meant to notice these turning points, but because Greg himself is a film-maker we are in on his knowledge:

But how self-aware is this story, really? Part of me thinks if this were truly self-aware the gender stereotyping would have been challenged, at the very least. On a surface level the gendering isn’t stereotypical — the girl asks the boy to the prom, for starters. But this is a foil: as I’ve mentioned above, the Female Maturity Formula is alive and well and goes completely unchallenged here.

Another gender trope that went unchallenged here: In comedy of all kinds the girls are disproportionately playing the ‘straight guys’. In this story, too, Greg regularly cracks jokes until Rachel smiles. Owing to her dire predicament, there is a ‘reason’ within the setting for her to be Greg’s straight guy. She exists narratively not only as a ‘love opponent’ but also as the instigator for Greg’s character arc. Because this girl dies he becomes a better person.

Of course, it’s not always the guy who gets to be funny. Sometimes it’s the girl who is funny. The guy might be depressive. She turns up to teach him to love life. This has been called the Manic Pixie Dreamgirl trope which ended up being applied far more widely than the person who coined that term ever wanted it to be, but it’s a useful concept because — again — despite the girl getting to be funny and cute, it’s the male character who undergoes the character arc. Whether she is the straight guy or the funny gal, female characters are not getting enough character arcs of their own. I would like a self-aware coming-of-age story to do that more often.