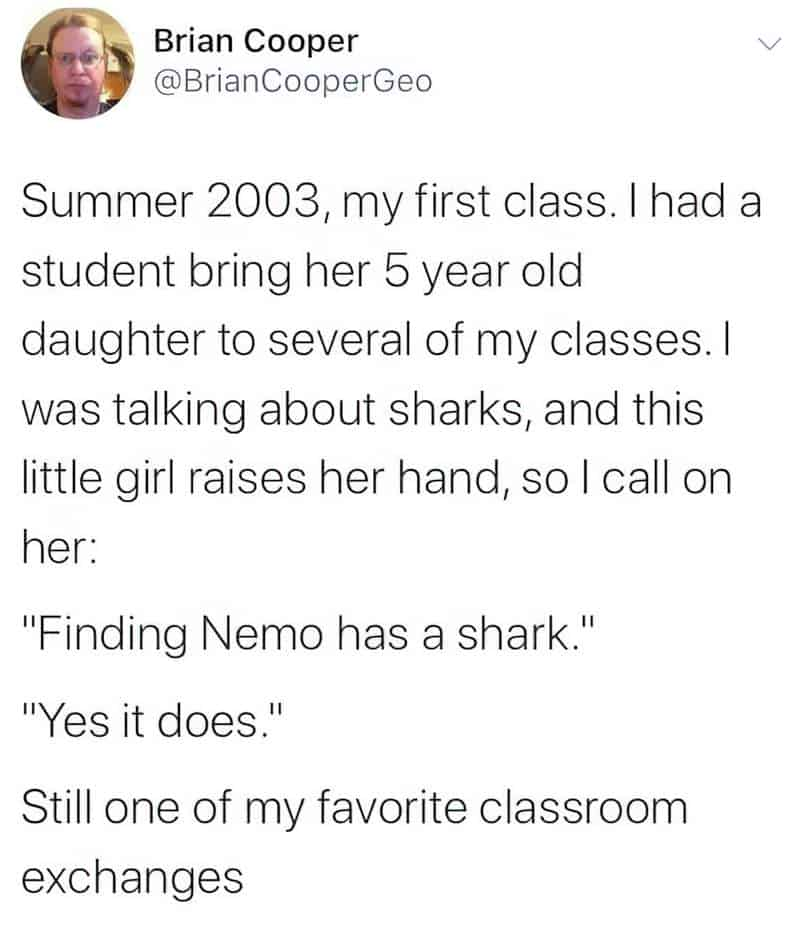

Sure, I’ve never been the target audience for Finding Nemo. I was already an adult when the film came out in 2003. But even my own offspring didn’t enjoy it. Could Finding Nemo be the most boring and unimaginative of all the Disney Pixar feature-length animations?

I won’t do a complete film study, because for once I can think of only two things to say:

- Finding Nemo hews closely to Odyssean Mythic Structure

- The anthropomorphised fish are your archetypal white American heteronormative nuclear family. There’s nothing fishy about them except their bodies and the underwater habitat. On the anthropomorphic scale, they sit towards the human end.

Which, okay fine, that’s what Disney is. And the minute they’re not that, they get the full force of conservative backlash.

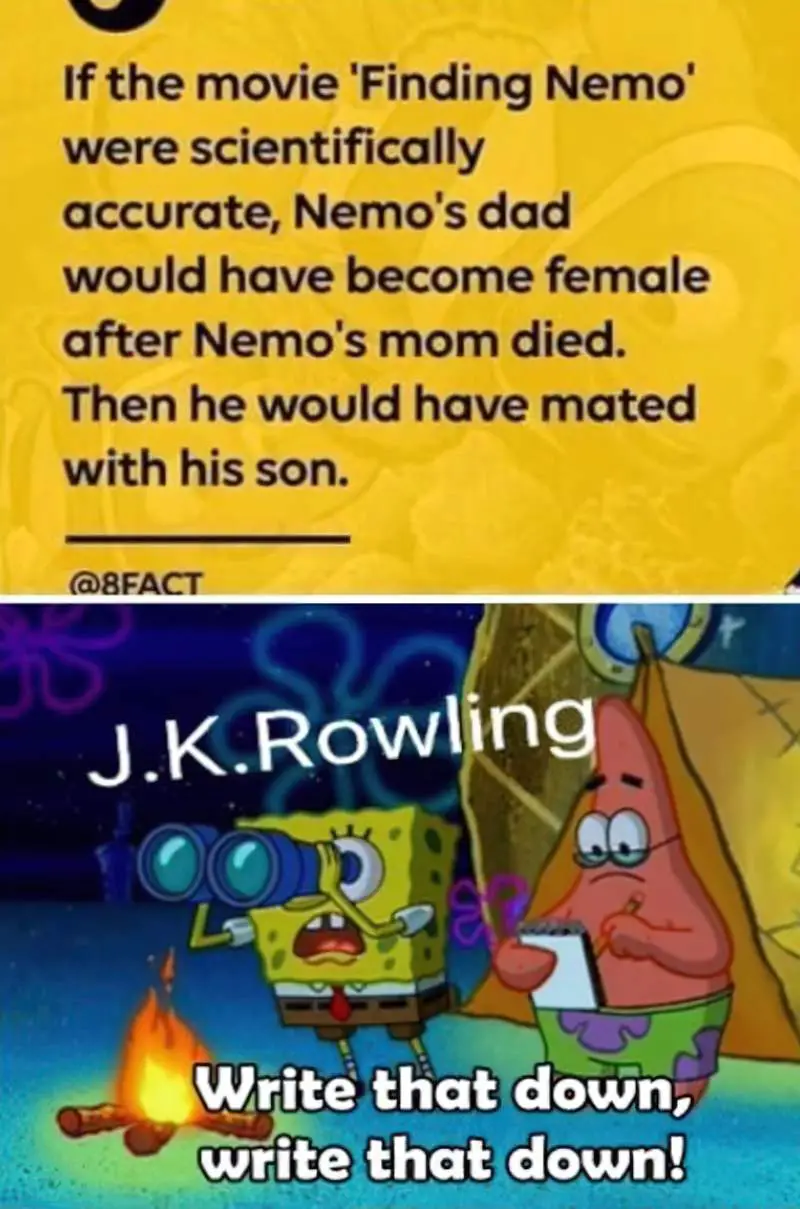

Now that Finding Nemo is 20 years old, and since the world is going through a gender revolution right now (hence the backlash), I’d like to take a moment to consider a contemporary Finding Nemo remake, which would be perfect for trans representation.

Why? Because:

CLOWNFISH ARE TRANSSEXUAL

- How biologists talk about sex and how people talk about sex in everyday life are two quite different things (unless you’re talking to intersex and trans people, who get this stuff at a fundamental level).

- A large proportion of people now understand that gender is a spectrum, but a smaller proportion are prepared to accept that sex is also a spectrum.

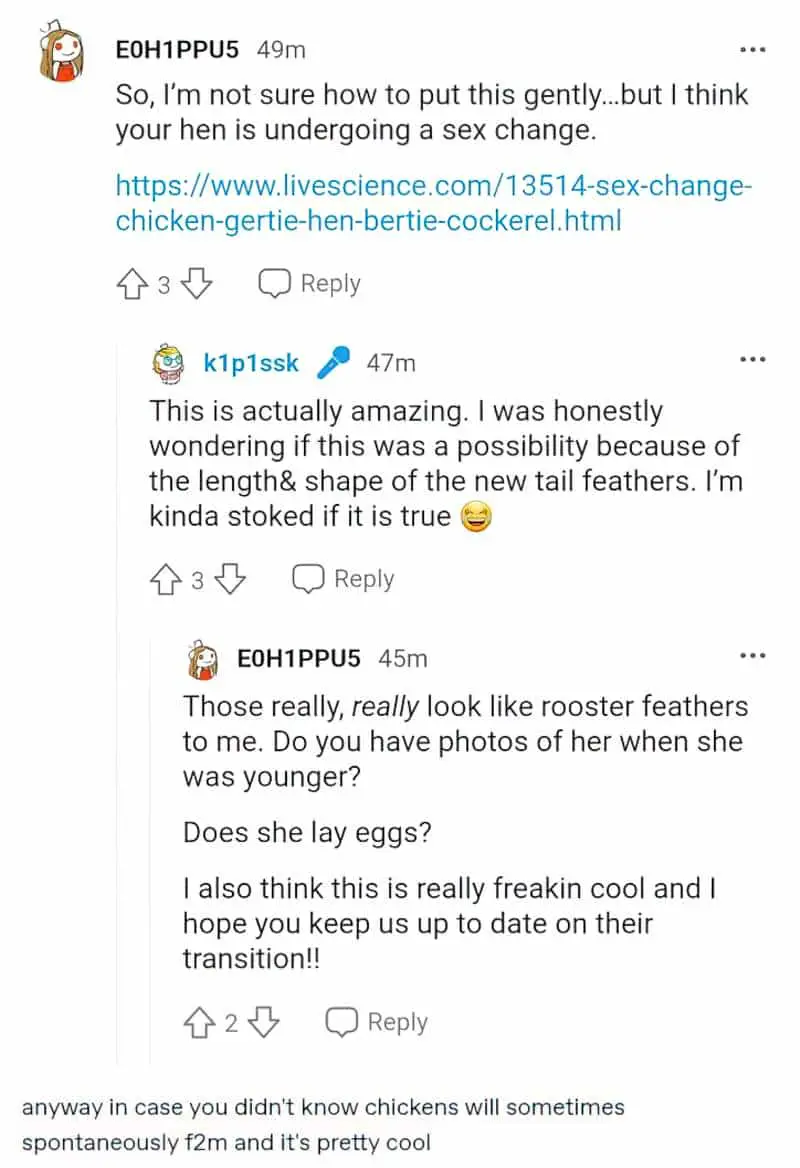

- Some species of fish exhibit what’s called sequential hermaphroditism (called dichogamy in botany). Depending on a set of environmental factors and the social structure of the school of fish they’re in, individuals can change their sex.

- If a head male in a population dies, one of the females will then become a male, and become the male reproductive partner in that species.

- This phenomenon is a great example of how binary sex, even in human animals, is not the whole story.

- The more we study biological sex and gender and intertwining factors, we know how complicated it is.

REFERENCES AND RESOURCES

Simon(e) Sun, neuroscientist, musician, artist and trans woman: “I knew I was trans because of science” at the ABC Science Friction podcast. Five minutes in she talks about how fish change gender.

The Talk Nerdy podcast, the one with Lucy Cooke, author of “Bitch: On the Female of the Species.” They discuss gender in the animal kingdom, how science has long gotten it wrong, and how studying female animals can teach us about ourselves.

A fierce, funny, and revolutionary look at the queens of the animal kingdom

Studying zoology made Lucy Cooke feel like a sad freak. Not because she loved spiders or would root around in animal feces: all her friends shared the same curious kinks. The problem was her sex. Being female meant she was, by nature, a loser.Since Charles Darwin, evolutionary biologists have been convinced that the males of the animal kingdom are the interesting ones—dominating and promiscuous, while females are dull, passive, and devoted.

In Bitch, Cooke tells a new story. Whether investigating same-sex female albatross couples that raise chicks, murderous mother meerkats, or the titanic battle of the sexes waged by ducks, Cooke shows us a new evolutionary biology, one where females can be as dynamic as any male. This isn‘t your grandfather’s evolutionary biology. It’s more inclusive, truer to life, and, simply, more fun.

“A sexist mythology has been baked into biology, and it distorts the way we perceive female animals.

In the natural world female form and role varies wildly to encompass a fascinating spectrum of anatomies and behaviours. Yes, the doting mother is among them, but so is the jacana bird that abandons her eggs and leaves them to a harem of cuckolded males to raise.

Females can be faithful, but only 7 per cent of species are sexually monogamous, which leaves a lot of philandering females seeking sex with multiple partners. Not all animal societies are dominated by males by any means; alpha females have evolved across a variety of classes and their authority ranges from benevolent (bonobos) to brutal (bees).

Females can compete with each other as viciously as males: topi antelope engage in fierce battles with huge horns for access to the best males, and meerkat matriarchs are the most murderous mammals on the planet, killing their competitors’ babies and suppressing their reproduction. Then there are the femme fatales: cannibalistic female spiders that consume their lovers as post- or even pre-coital snacks and ‘lesbian’ lizards that have lost the need for males altogether and reproduce solely by cloning.”

Lucy Cooke

Andrew Stanton is the big name behind the film Finding Nemo. Listen to his TED talk called “Clues To A Great Story” (or my commentary on it, with notes.)

Artwork was generated using SDXL 0.9.

WHY FISH DON’T EXIST

In this episode of Talk Nerdy, Cara is joined by science reporter, producer, and Radiolab co-host Lulu Miller to talk about her new book, “Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life.” Lulu shares the incredible story of taxonomist David Starr Jordan, and in doing so, opens up the conversation to the power and consequences of imposing order on the world around us in the form of labels, categories, and impossible constraints.

GENDER BIOLOGY

Cara dives deep into gender biology with Dr. Anne Fausto-Sterling, the Nancy Duke Lewis Professor Emerita of Biology and Gender Studies in the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology and Biochemistry at Brown University. They talk frankly about gender and sexuality, including a discussion of its scientific, political, and social influences.

YOUR INNER FISH

Also at Talk Nerdy, Cara joins paleontologist, anatomist, evolutionary biologist, and popular science writer Neil Shubin (Your Inner Fish, The Universe Within) to talk about his discovery of Tiktaalik roseae, a key species linking all living tetrapods to our aquatic ancestors.

Unlike the star of Disney’s Finding Nemo, real-life common clownfish are not keen on sharing their home with members of their own species.‘Nemo’ clownfish drive away species with same stripes, study suggests, The Guardian