Noir is a visual aesthetic in storytelling associated with certain plots and character archetypes. The term was popularised in the field of film criticism, hence film noir. It comes from several movements, notably the hard-boiled detective tradition of popular cheap paperbacks. Think Raymond Chandler, uber hard-boiled writer.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF FILM NOIR

- In the 1930s, French directors such as Marcel Duhamel translated American spechard-boiled detective novels for a French speaking audience.

- Duhamel is the standout example. He named his economy priced paperbacks Serie Noire. The series included the works of Raymond Chandler, James M. Cain and others. These proved very popular with French readers.

- It seemed fitting that the phrase used to describe these books would also apply to the Hollywood film adaptations.

- Although this feels like an American Hollywood phenomenon, the history of the term is, ironically, French and was slow to catch on in America. Film noir was used for the first time in 1946 by Nino Frank in the article “Un Nouveau Genre ‘Policier’: L’Aventure Criminelle” published in L’Ecran Francaise (“A New ‘Police’ Genre: The Criminal Adventure,” in The French Screen). But it took a decade for the term to take off in America. (Partly because the article was in French and took a while to be translated. In fact, nothing was written in English on this subject until 1970.)

- Film noir means ‘black film’ in French. A more apt translation might be ‘film of the night’. The plural is films noirs.

- Film noir is a 20th century descendent of the grim romanticism of the 1800s.

- It is very much linked to a specific era in film, like German Expressionism or French New Wave. Noir film is very much of the American urban 1940s — mid 1950s. (No one agrees on exact dates. Some critics only include the 1940s. However the film noir heyday happened between 1947 and 1950.) Samuel Fuller (House of Bamboo, 1955; Pickup on South Street, 1953) is well-known for excellent chronicler of cities even though his movies were filmed on sound stages. (He both directed his own noir and wrote them for other directors.)

- Film noir was a brand new look influenced by 1930s gangster films (for their hopelessness and pessimism), American hard-boiled literature (for its crime plot lines), German Expressionism (for its lighting and framing) and World War 2 (for the rise of a fatalistic attitude following the rise of dictators, genocide, death and societal collapse).

- The technology of Technicolour wasn’t exactly well-suited to noir. Nor was Cinemascope and Panavision. And when Americans had TVs in their own living rooms, theatres had to offer something not available in the living room. Film noir doesn’t look especially spectacular in a theatre, compared to those other technologies at least, so fewer films noirs were made.

- By the 1950s, American audiences had lost a taste for films noirs anyway. Everything was looking pretty rosy. Most people were prospering, Eisenhower was president, no bomb had fallen. The themes of films noirs appealed to audiences living in times of uncertainty. (Then along came Vietnam in the 1960s.)

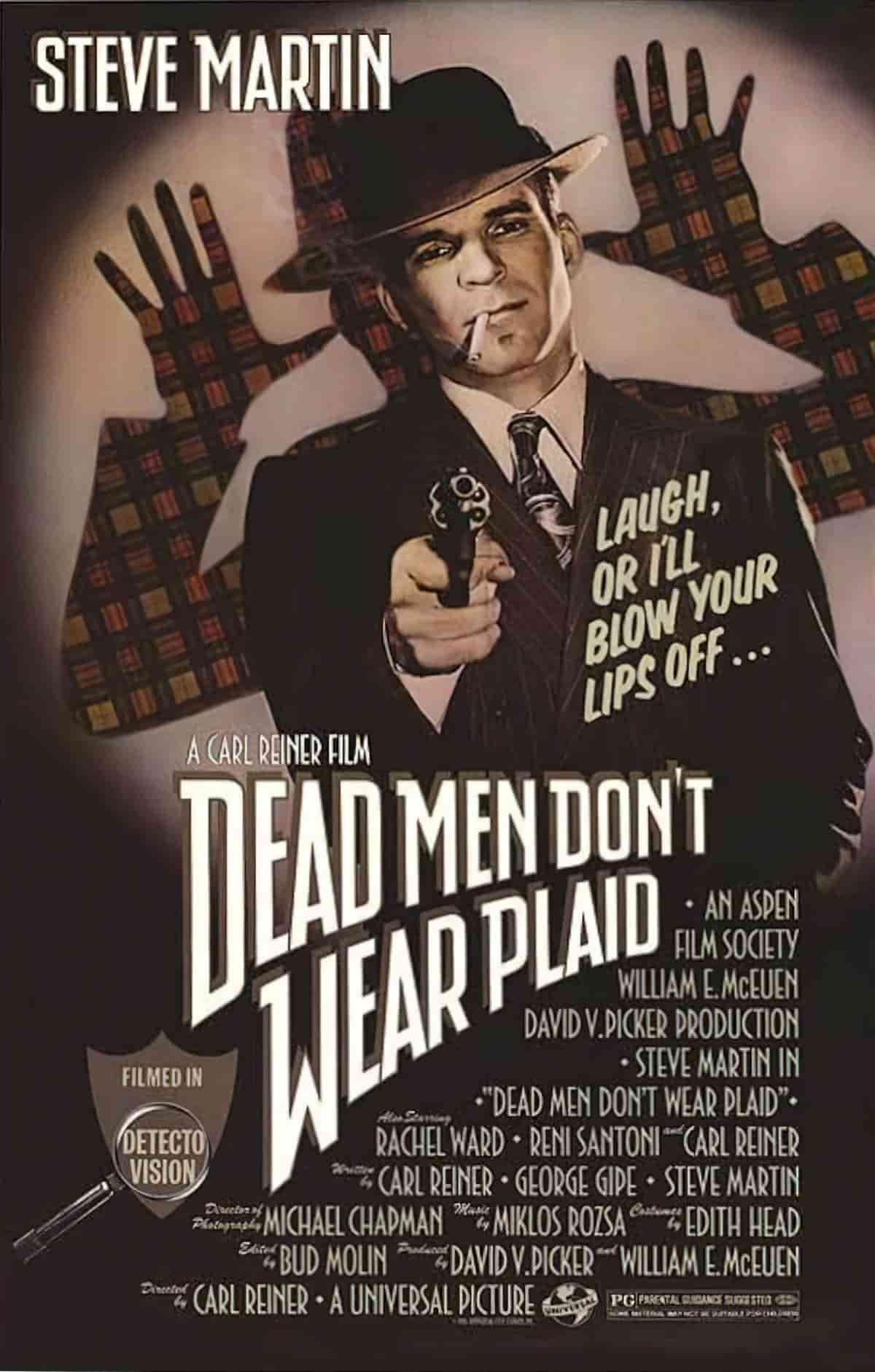

- For today’s audiences, it’s easier for film-makers to use film noir aesthetics to mock a genre rather than utilise it in a serious way. An example of a spoof film noir: Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid (1982).

SPOOF NOIR

EXAMPLES FROM THE HEYDAY OF FILM NOIR

Owing to the war there was very little noir released 1942-3. Noir tends to be critical of American life, and that’s not what Hollywood audiences wanted to see on screen when patriotism was called for. Americans were watching films like The Pride of the Yankees and Yankee Doodle Dandy at the start of WW2. Not film noir.

However, things changed in 1944. After wartime repression, dark movies come back darker than ever:

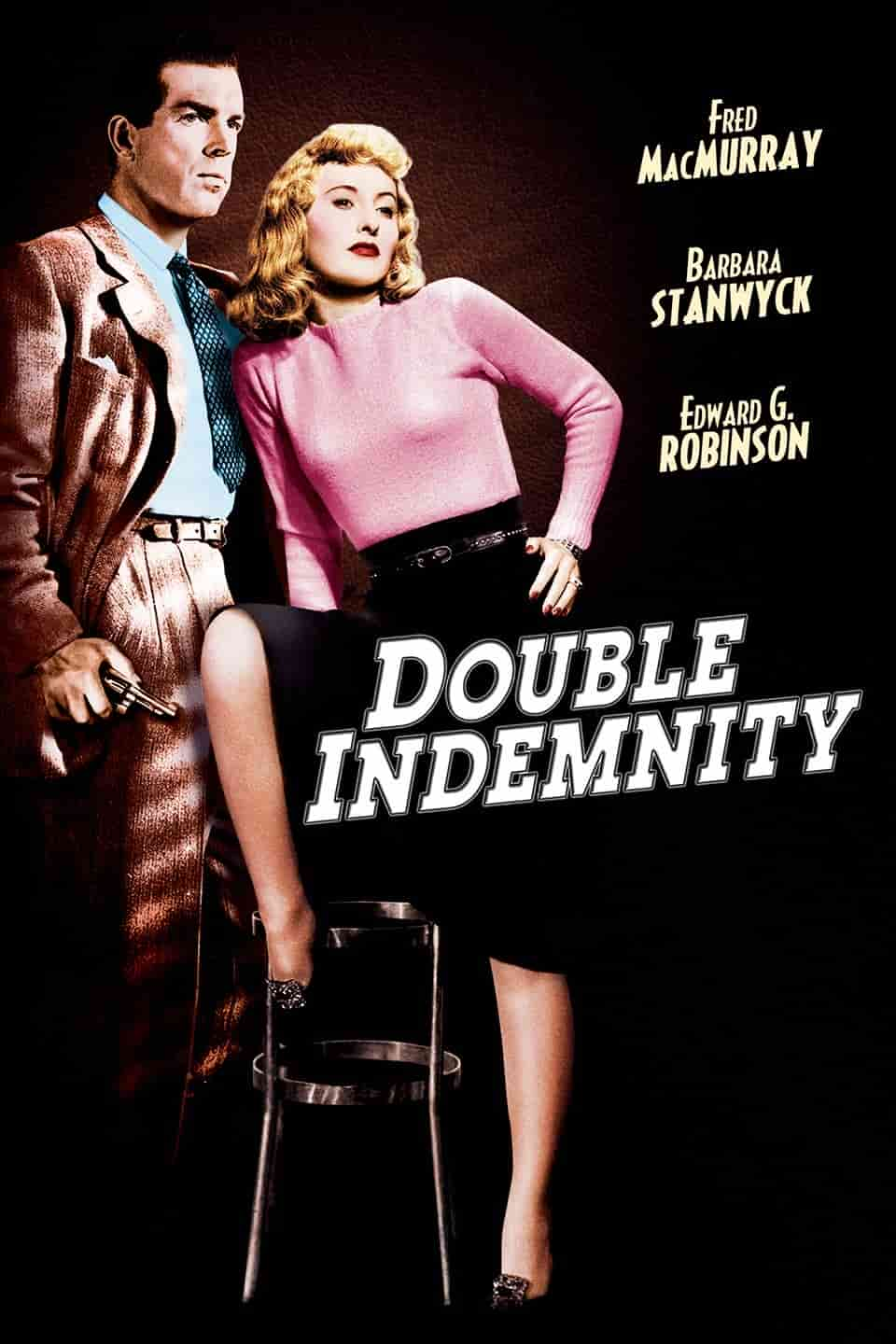

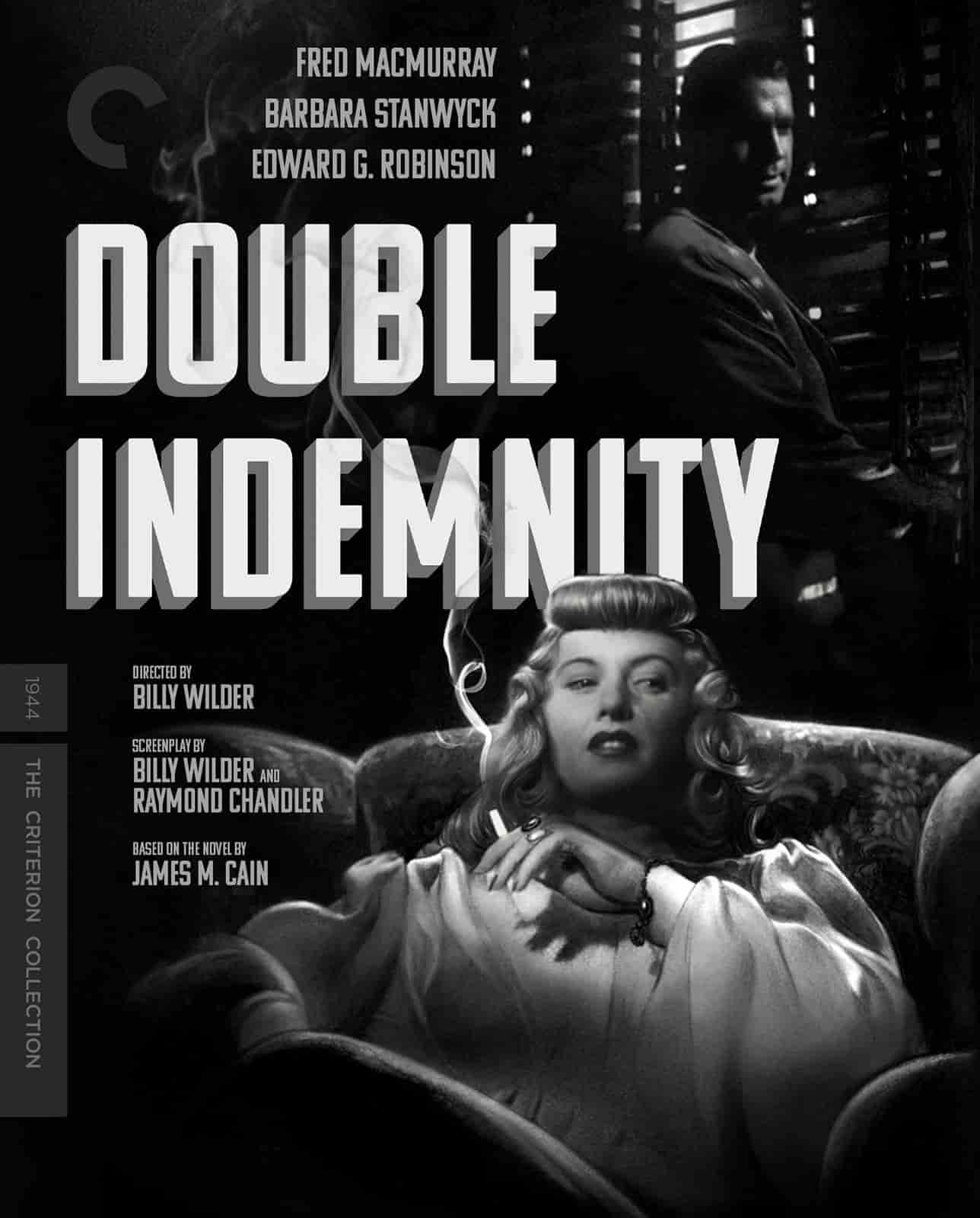

- Double Indemnity (1944)

- Laura (1944)

- Murder, My Sweet (1944)

- Cornered (1945)

- Mildred Pierce (1945)

- Ministry of Fear (1945)

- Woman in the Window (1945)

- The Lost weekend (1945) — which won Academy awards

- The Big Sleep (1946) — with a notoriously convoluted plot

- The Killers (1946) — Robert Siodmak

- Stray Dog (1949) — Akira Kurosawa

- Repeat Performance (1949) — Alfred L Werker, since restored by the Film Noir Foundation and released by Flicker Alley. An insightful commentary into unreachable standards often expected of women.

- Niagara (1953) — Henry Hathaway. An example of Technicolor Noir. Marilyn Monroe is an unhappily married woman. Though flawed, some sympathy is directed towards the woman, even though she cheats on her husband.

- Forty Guns (1957) — This is a Western but noir sensibility is evident. The noir psychology comes out as violence.

- Experiment in Terror (1962) — Blake Edwards

- Assault on the Pay Train (1962) — Roberto Farias, made in Brazil

- Tocaia no Asfalto (‘Ambush on the Asphalt’, 1962) — Roberto Pires (also made in Brazil

- Pierrot le Fou (1965) — Jean-Luc Godard

- The Incident (1967) — Larry Peerce, a portrait of America as a melting pot of racial and classist tensions

- The Secret (1979) — debut of director Ann Hui. Noir is now being used to talk about the lives of women. This one sits between thriller and human drama, and focuses on a number of women’s lives across different generations. Unfortunately it has been lost in its original format. However it was recently restored by the Hong Kong Film Archive and Magyar Nemzeti in Hungary.

FEATURES OF FILM NOIR

There has never been full consensus regarding which stories count as noir and which don’t. But here are some general pointers. It’s easier to pinpoint individual elements than say which films have enough of them to count as noir. To get around this, some critics have coined phrases like film gris (film grey) and semi-noir to get around arguments about what counts as ‘true noir’.

what Pauline Kael wrote in her criticism of auteur theory in the 1960s: that in order to continue to praise a supposedly bad or unworthy film by a director you love, you would either consider it an outlier or find only a few moments to praise. In film criticism, that may require dishonesty; in this scenario of collection and celebration, it’s a pleasure and a benefit. A few films will come along that don’t really belong to the genre at all, but in this context, considering them noir can bring out something unique.

Eloise Ross at Overland

GENRE

Is film noir a genre? People argue about this. Some say definitely not. Genre is about characters and their conflict dynamics, settings and shared iconography whereas noir is about elusive qualities such as mood, style and tone.

Noir is the frequent aesthetic applied to hard-boiled detective crime. But you also get noir Westerns, noir Gothic suspense and even noir comedies. (This shouldn’t be a surprise, since transgression plots in comedies and thrillers have identical beats.)

So is noir a genre in its own right? The answer depends whether you think genre can be determined by aesthetics, because film noir can feature all sorts of settings, characters and iconography. Listed below are the features of so-called (and arguable) ‘true noir’.

- Film noir is an example of paranoid fiction. Paranoid fiction overlaps with various genres, most commonly dystopian fiction and science fiction. The setting tends to feel gritty real (and not at all dreamlike).

- Film noir is an aesthetic pasted over a crime, action, thriller blend. (The crime is usually murder.)

- The noir aesthetic is very common in the subgenre of thriller known as the ‘transgression thriller‘ a.k.a. the noir thriller. The main character transgresses (makes an error of moral judgement driven by his own weaknesses and desires.)

- The tagline of film noir might be: “where women have a past; men have no future” (Embedded in this messaging is that women are evil when they are sexually experienced. However, this is also what makes them so desirable.)

- No happy endings. (This is where noir departs from gangster films, in which bad guys receive punishment, restoring order.) Film noir characters aren’t looking to the future. They’re only trying to survive the night. At the end of a film noir story, heroes remain ambivalent about evil.

- Some films aren’t noir all the way through but might include a very film noir scene or sequence

NARRATION

- Conventional narrative choice of film noir: the story is told from the chump’s point of view, often in flashback

- Flashback is part of a notoriously convoluted plot, often including voice over narration.

SETTING OF FILM NOIR

- dark and pessimistic settings match the dark mood in both theme and subject

- a focus on the harsh world of private investigators, police detectives and the criminals they chase

- a setting filled with fear

- a stifling environment of repeating eternal nights in one-room walk-ups

- very typically urban, with chiaroscuro lighting, all-night diners, alleyways, back doors of upmarket establishments, apartment buildings with high rates of turnover (which means no neighbours to help you if you get into bother).

- If they’re not filmed in black and white, they are low saturation.

- rain-slicked city streets reflecting neon signs at night which blink through the windows of shabby residential hotels

- Cars of this era are at peak largesse with regards to both size and power. The cars of film noir all seem to have running boards. ( A running board is a platform attached to a vehicle’s doors that helps passengers easily board and leave the car.)

- a corrupt milieu devoid of human sympathy (In many stories, women are utilised as the caregivers, but here women are also evil, meaning there’s literally no one left to offer a man comfort and sympathy.)

- a soundtrack of sirens, screams and sobs

- the criminal underworld is symbolic enfer (Hell)

CHARACTERS IN FILM NOIR

- Everyone always seems to be smoking.

- Taxi drivers and bartenders are jaded. They’ve seen it all, and they’re not about to help the main character in peril. Basically, the hero is alone. No one will help. He may be surrounded by people but they are automatons to him.

- The lead character is usually a good guy detective or lawyer or someone with skills that can be used for evil. There will be a save the cat scene showing he’s good at heart, for example he protects a kid who shouldn’t be drawn in by the dangerous gangsters.

- He’ll be on first-name terms with homicide detectives. He may be an office worker but he doesn’t look down on the working class. In fact, he considers himself one of them at heart. This attitude will be conveyed by him calling all the guys in his world friendly diminutives such as newsies, junkies, jockeys, cabbies etc.

- The chump hero is driven by something from within: Greed, lust and ambition. He may also have a drinking problem, drinking frequently out of the office bottle. The difference between a noir thriller and a conspiracy thriller: The noir hero is driven by one of his own weaknesses whereas in a conspiracy thriller, others conspire against him. He simply responds. The advantage to a film noir hero with internal weaknesses: Characters with weaknesses feel more realistic, more sympathetic and are definitely more interesting to watch.

- However, the heroes of film noir frequently make decisions which never make sense to the audience. We are supposed to sit back and watch the spectacle of them going about things. Don’t ask why. This will ruin it for you. The heroes are a tangle of moral contradictions, sometimes acting morally, other times immorally. These guys simply don’t really care about staying on the ‘right’ side of the law, or of society. They drift between social groups, wraithlike. He never really fits in anywhere. All of these men are alienated.

- The chump is seduced by a very specific character called a femme fatale, a ‘disastrous woman’ who uses all of her feminine wiles to get the man to do as she pleases. Perhaps she comes into his office at work and requests his help. She’s a sort of modern day succubus.

- Misogyny noted. Enduring male fantasy also noted, showcasing a man’s desire to provide help and services to a woman, which is not in itself a negative thing. Likewise, it is a common female fantasy to be sexually powerful and independent. she is also smart. Part of the interest for the audience: What will the femme fatale do next? However, the story of sexy woman as evil temptress stretches further back than Adam and Eve. Other messages which cannot be disentangled from these plots: Sexually confident women are also evil; women are to blame for men’s own downfall; women who do not remain in the home and offer comfort and solace to men are very interesting, but likely to end up dead. (This is the Harlot’s Progress Plot, super popular until about a century ago.)

- Femmes fatales are one-dimensionally cold, frustrated and greedy. Unlike the men, they’re not suffering from some existential crisis which might explain why they are like this.

- The film noir femme fatale has a specific fashion sense: floppy hats and unsubtle make-up (heavy mascara, lipstick). She wears high heels, red dresses with low necklines, gloves up to her elbows. She is good at mixing drinks and calls doormen by their first name.

- Even when the femme fatale is dead, with her limbs sprawled every which way on the floor, her hair and make-up remain flawless.

- The innocent man (chump) invariably decides to do the woman’s bidding. He commits a crime of some sort (most often murder). She sets him up to take the fall for it, escaping with some kind of treasure that only the innocent man can help her attain.

- Men wear fedoras (an enduring symbol of hegemonic masculinity), suits (the enduring symbol of capitalism).

- Some critics think ‘true noir’ must star professional criminals, not one-time crims. (That might attract the term film gris.)

One difference between film noir and more straightforward crime pictures is that noir is more open to human flaws and likes to embed them in twisty plot lines.

film critic Roger Ebert

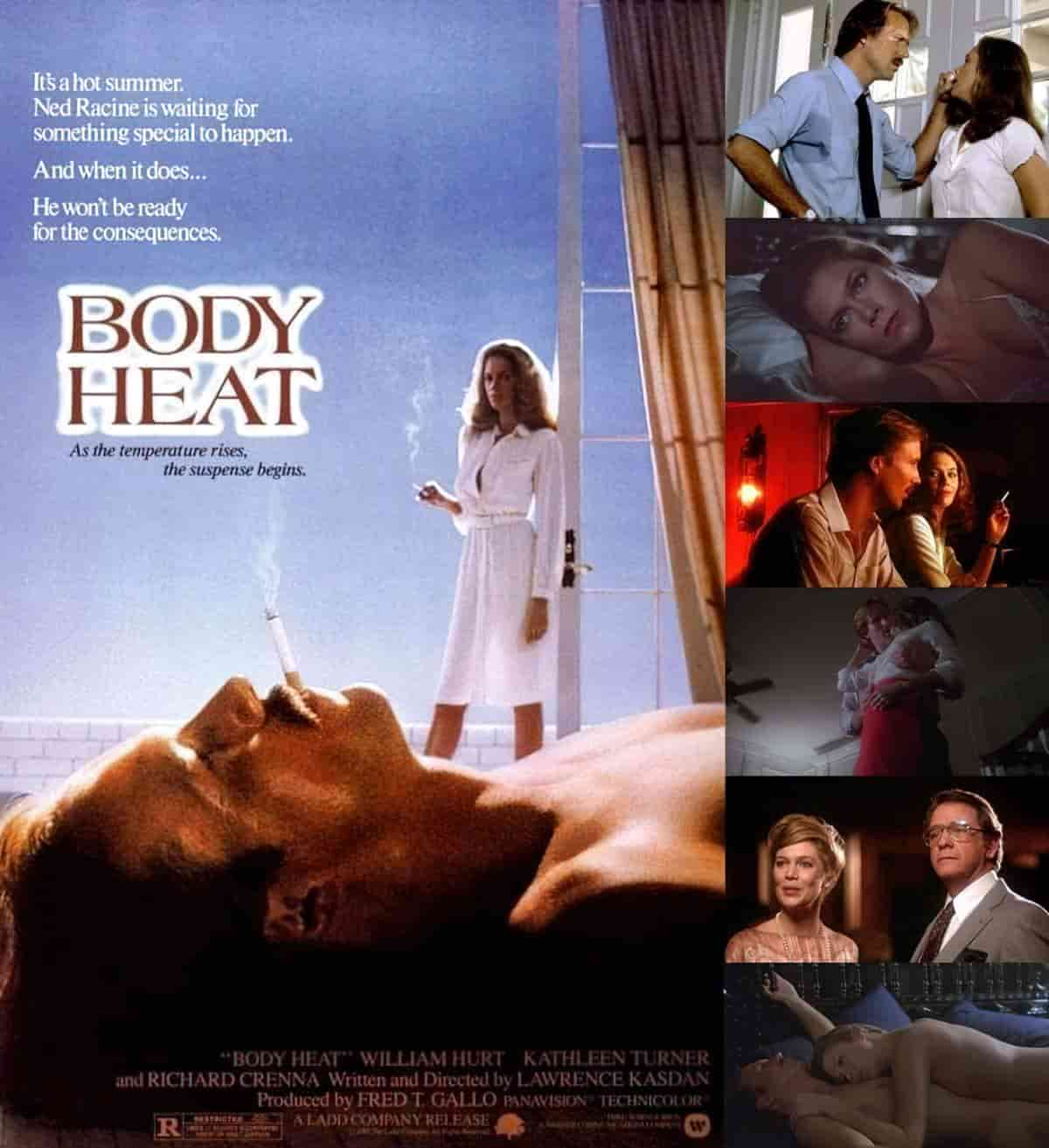

NEO NOIR

Veronica Mars is an update on 1940s noir. Rather than set in a dark urban environment, the story is set in a school.

THE ENDURING INFLUENCE OF FILM NOIR

Even if you haven’t watched the hard-boiled film noir of the mid 20th century, if you’ve watched apocalyptic contemporary film, those pictures are the grandchildren of the film noir tradition:

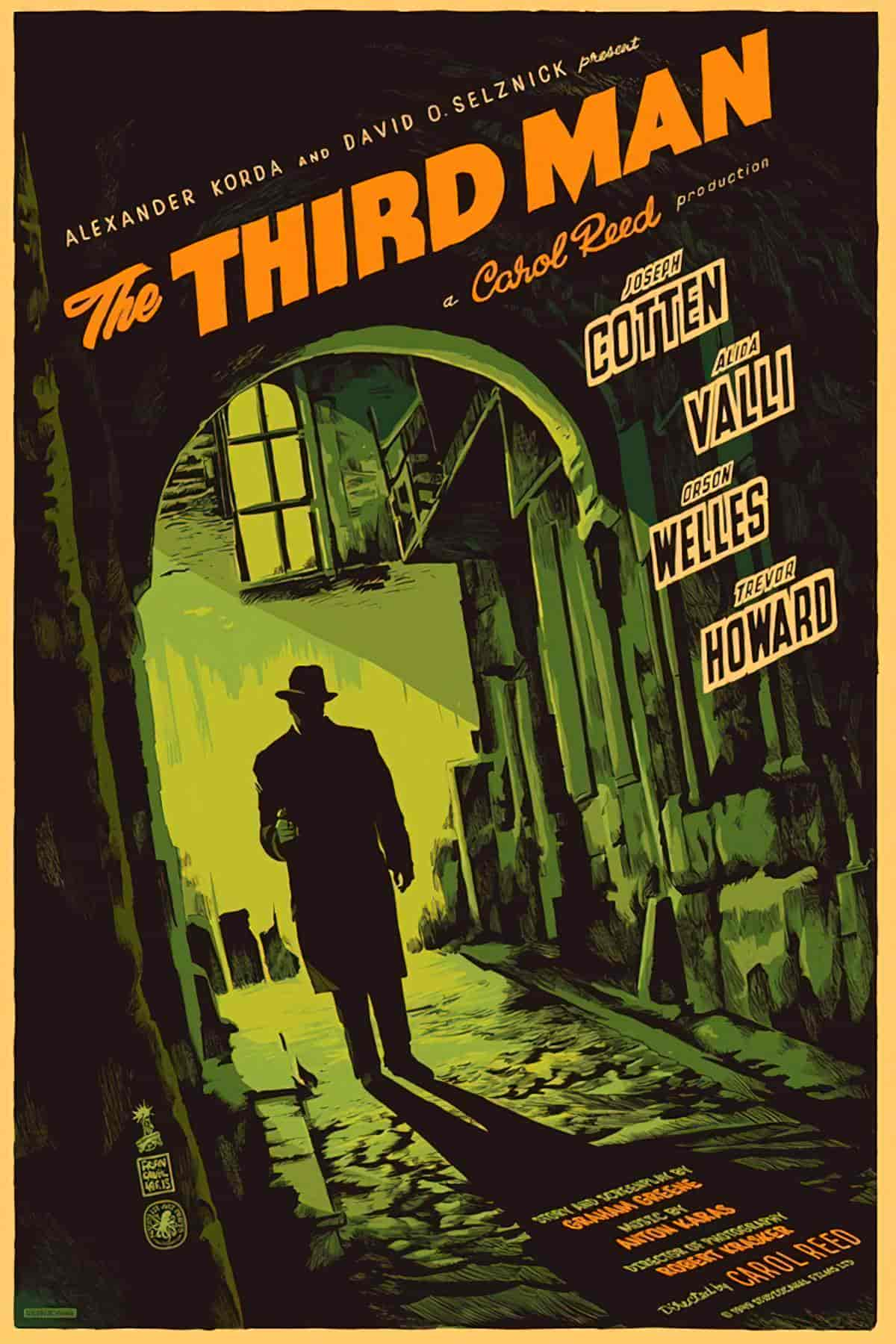

As a cinematographic feature, emptiness has had a long and continuing history, often contributing to the specific genre conventions of a film. Film noir in particular has extensively relied on empty or abandoned city spaces, such as, for example, the destroyed post-war landscapes of Vienna in The Third Man (1949).

Moreover, it has also seen a recent revival as part of the ongoing success of post-apocalyptic fiction, such as in the empty city streets of New York City in I Am Legend (2009) or the grim landscapes of The Road.

Drawing particularly on motifs of destruction and decay, the visual aesthetics of emptiness have given a new meaning to empty cities which has also led to an increase in representations of ruins, for example in photography and exhibitions. …

Exploring the dynamics of anxiety and sublime beauty that are associated with places of ruin, [Dora Apel] argued that post-apocalyptic narratives also ‘render our own society as other and encourage us to ask whether the empire of capital represents lasting progress or a road to decline’.

Landscapes of loss: the semantics of empty spaces in contemporary post-apocalyptic fiction by Martin Walter, from the book Empty Spaces: Perspectives on emptiness in modern history, 2019

WHITE NOIR

Beginning in the 1990s, ‘white noir’ began to take off. Fargo (1996) by the Coen Brothers was a tentpole example of dark crime stories which are set in snow, largely during the day, rather than in urban areas at night.

EXAMPLES OF CONTEMPORARY NOIR

- Ivans xtc. (2000) — Bernard Rose, which reads in plot like a mid 1940s example of ‘true noir’

- The Square (2008) — Nash Edgerton, made in Australia. A chump goes astray chasing after a femme fatale.

- Decision to Leave (2022) — Park Chan-Wook (Parasite, Squid Game), in which the detective blames himself for the death of two people because he chose to bury evidence that a woman committed an earlier murder.

Each November, fans of film noir get together online for #Noirvember. Participants watch noir all month.

The Origins of Cool in Postwar America

In his new book, The Origins of Cool in Postwar America (University of Chicago Press, 2017), Cultural Studies scholar Joel Dinerstein explores the cultural history of cool and the codes that defined the style and attitude of this relatively new concept. Using cultural icons such as Lester Young, Humphrey Bogart, Albert Camus, Billie Holiday, Jack Kerouac, Marlon Brando, Miles Davis, and Lorraine Hansberry to name a few, Dinerstein weaves an image of cool in the 1940s and 1950s as it intersects jazz, film noir, literature, and existentialism. Well researched and compellingly written, The Origins of Cool in Postwar America examines the ways in which popular culture works to define cool throughout the Cold War. Dinerstein’s work interrogates cool, presenting the way in which individuals show how cool is a way of rebellion and resistance against racism or other cultural and social norms. Cool brings a hope to individuals during cultural shifts that Dinerstein presents in this thorough and thoughtful exploration into cool and the icons who exuded the term.

New Books Network