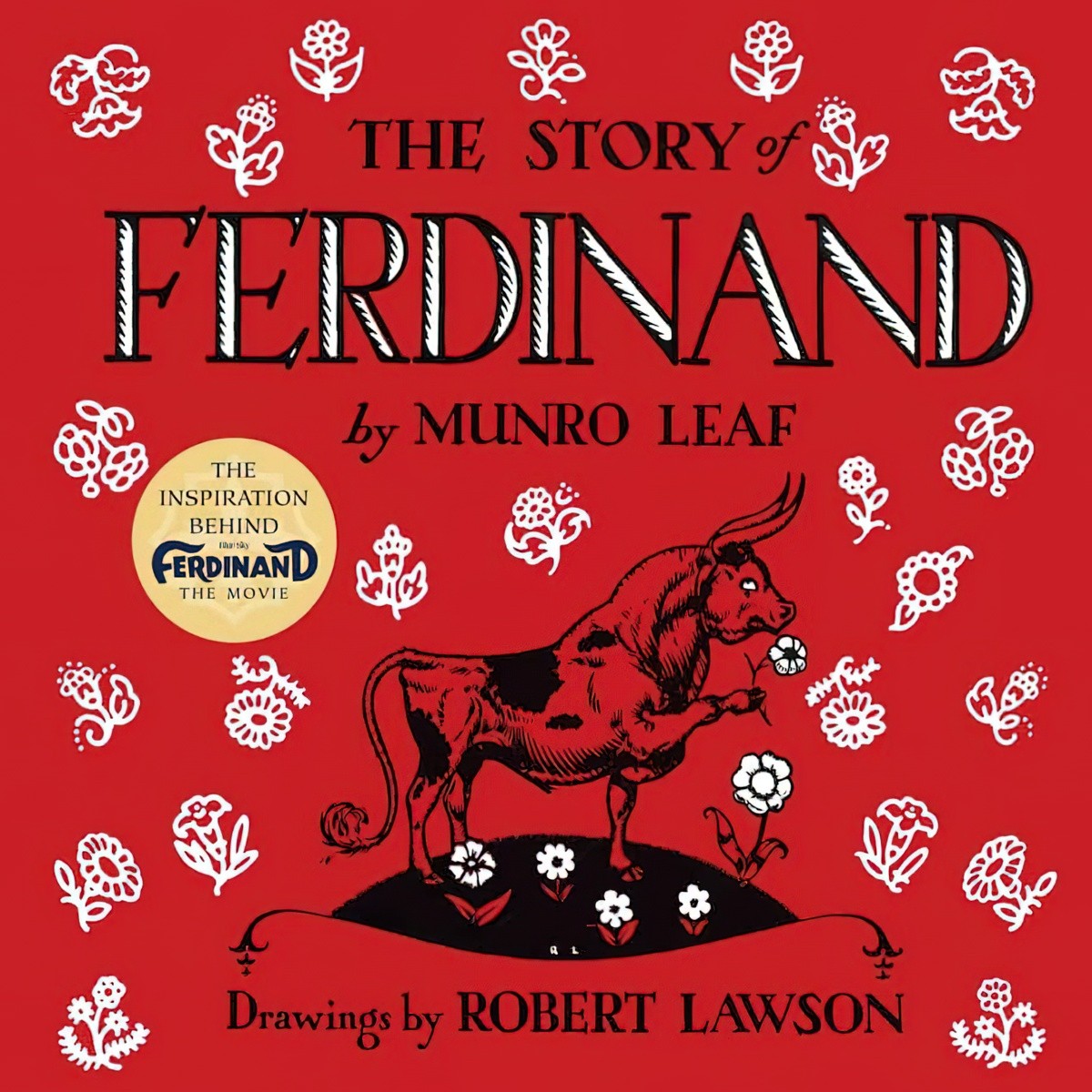

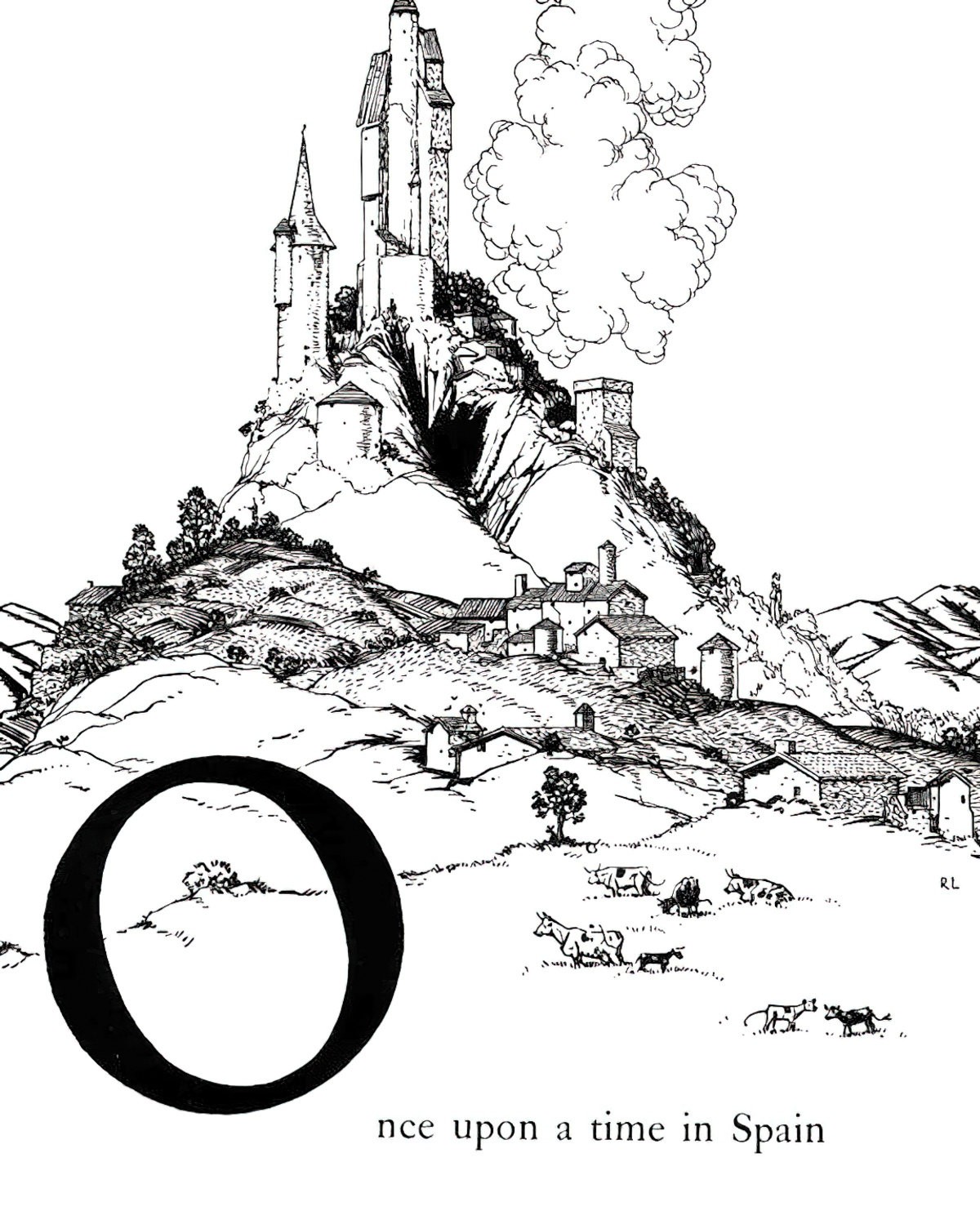

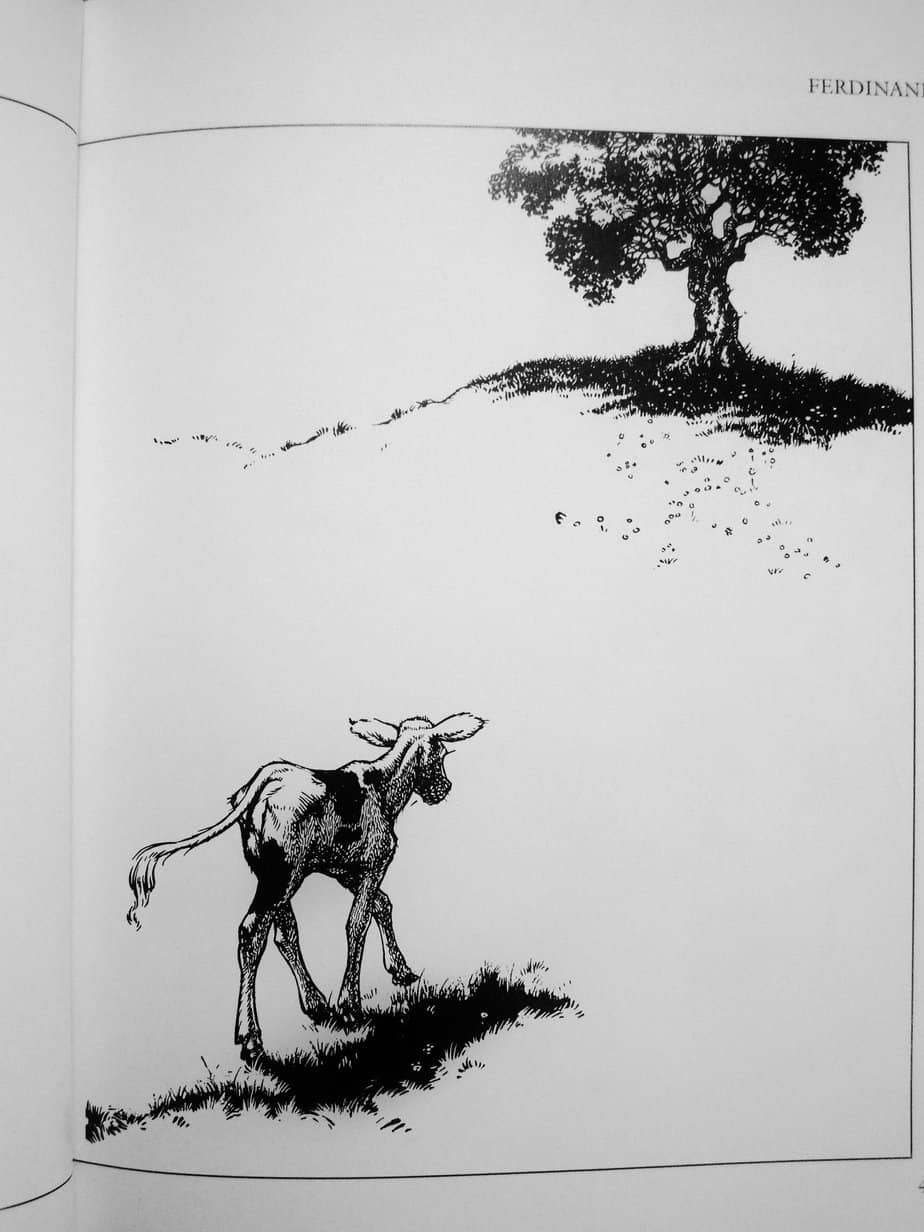

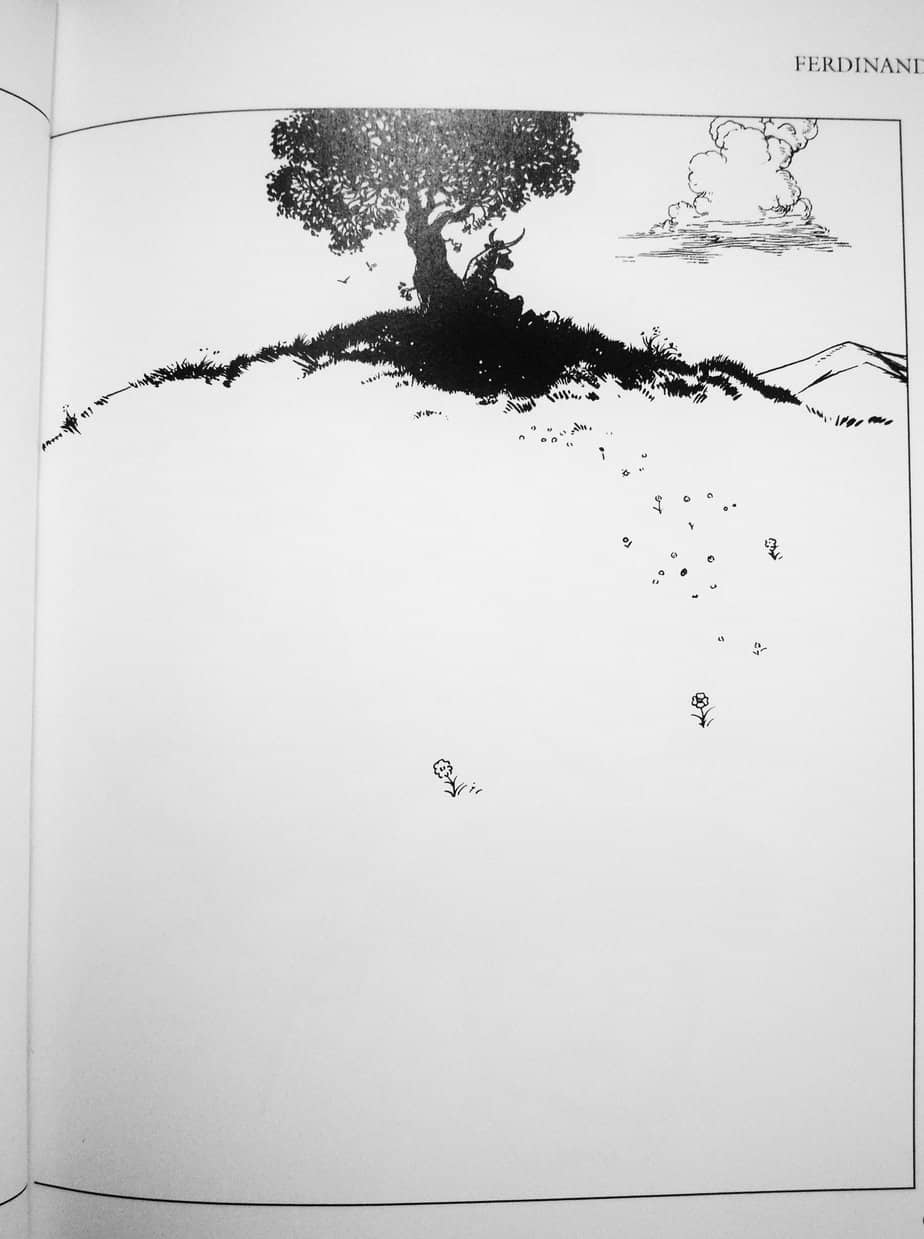

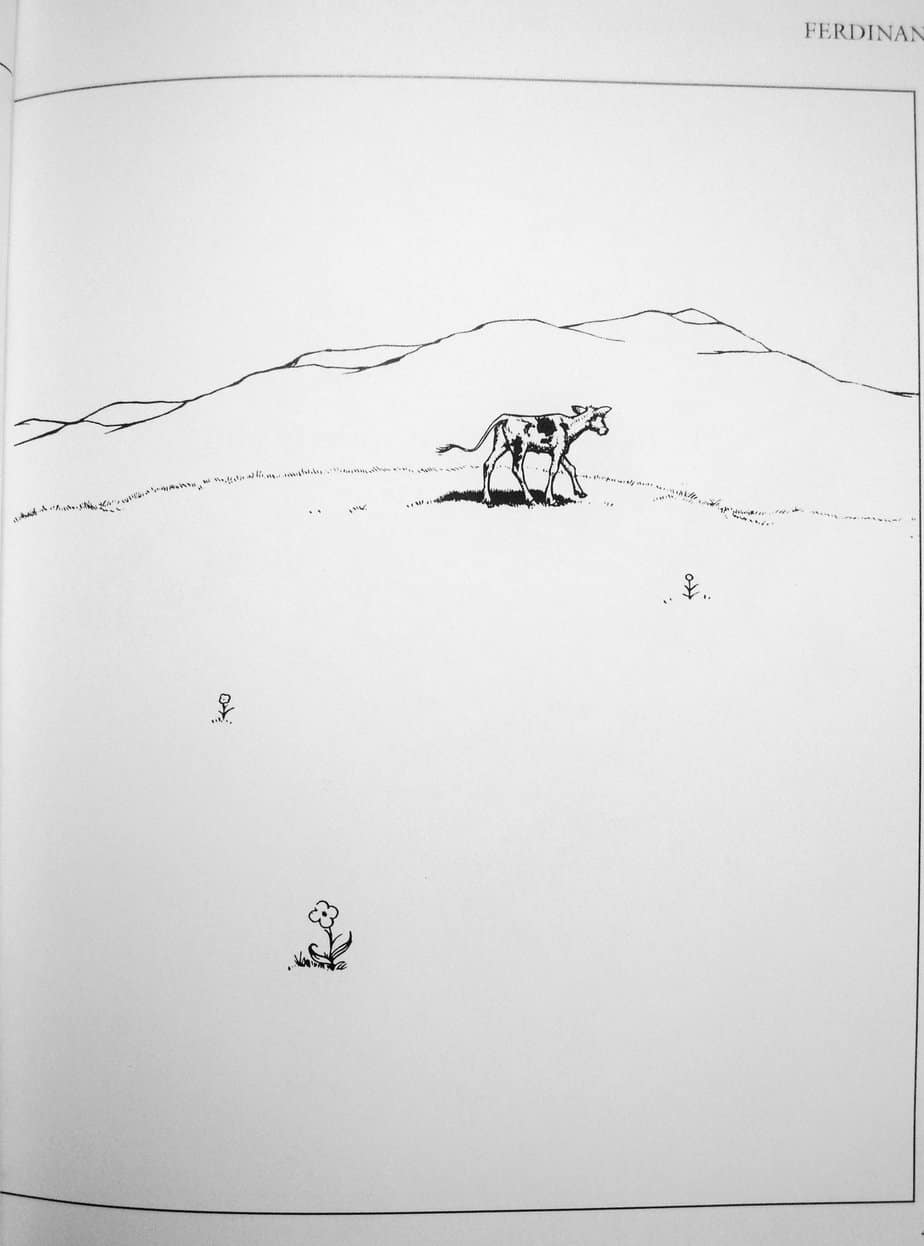

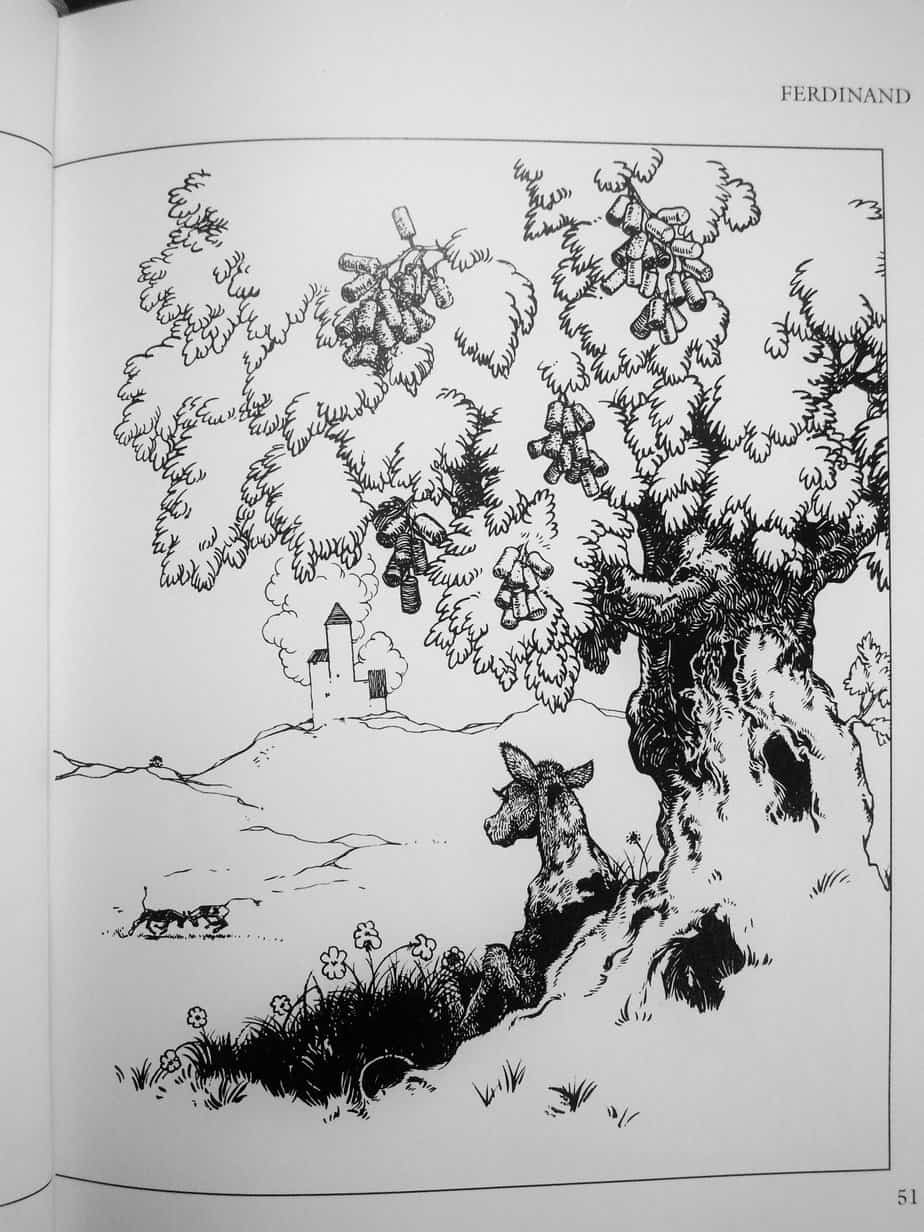

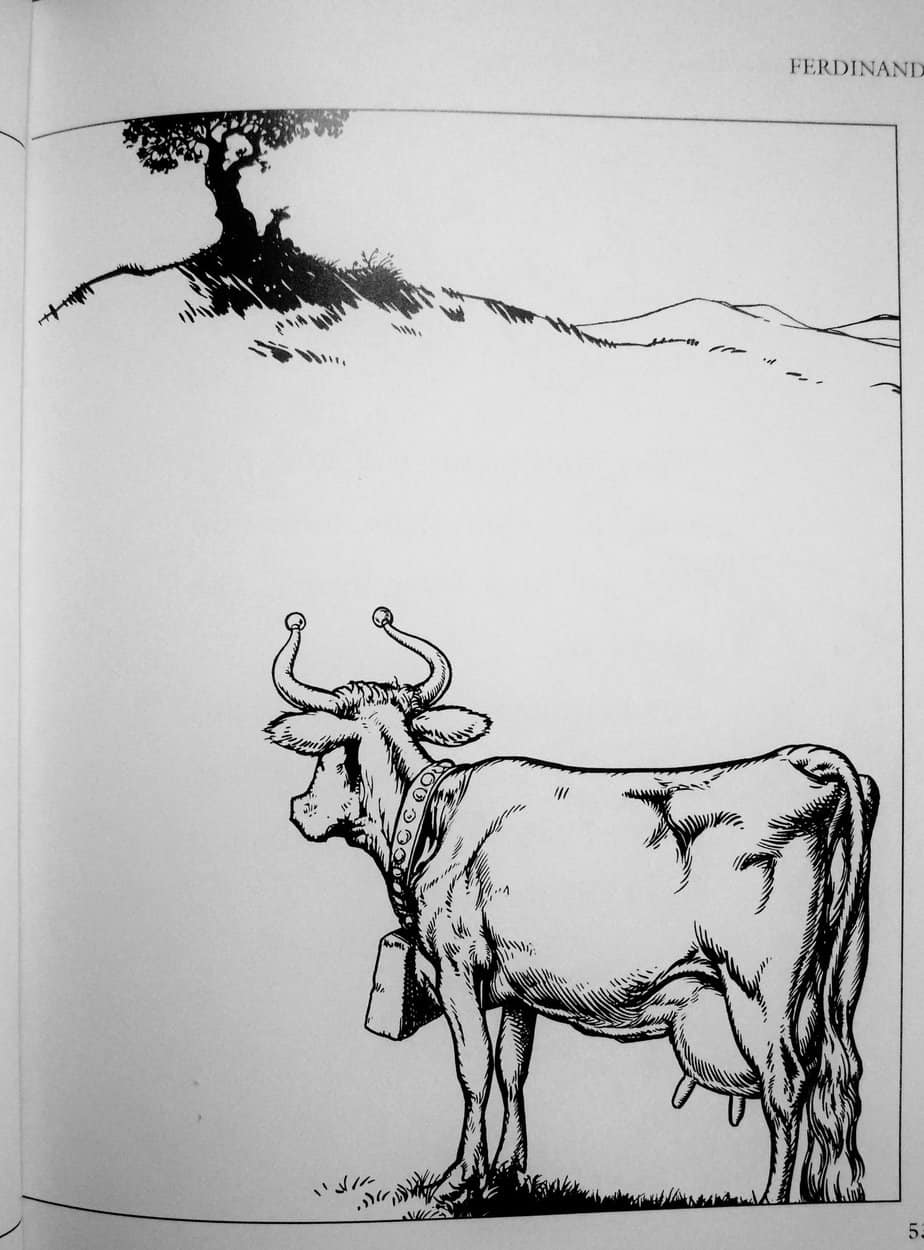

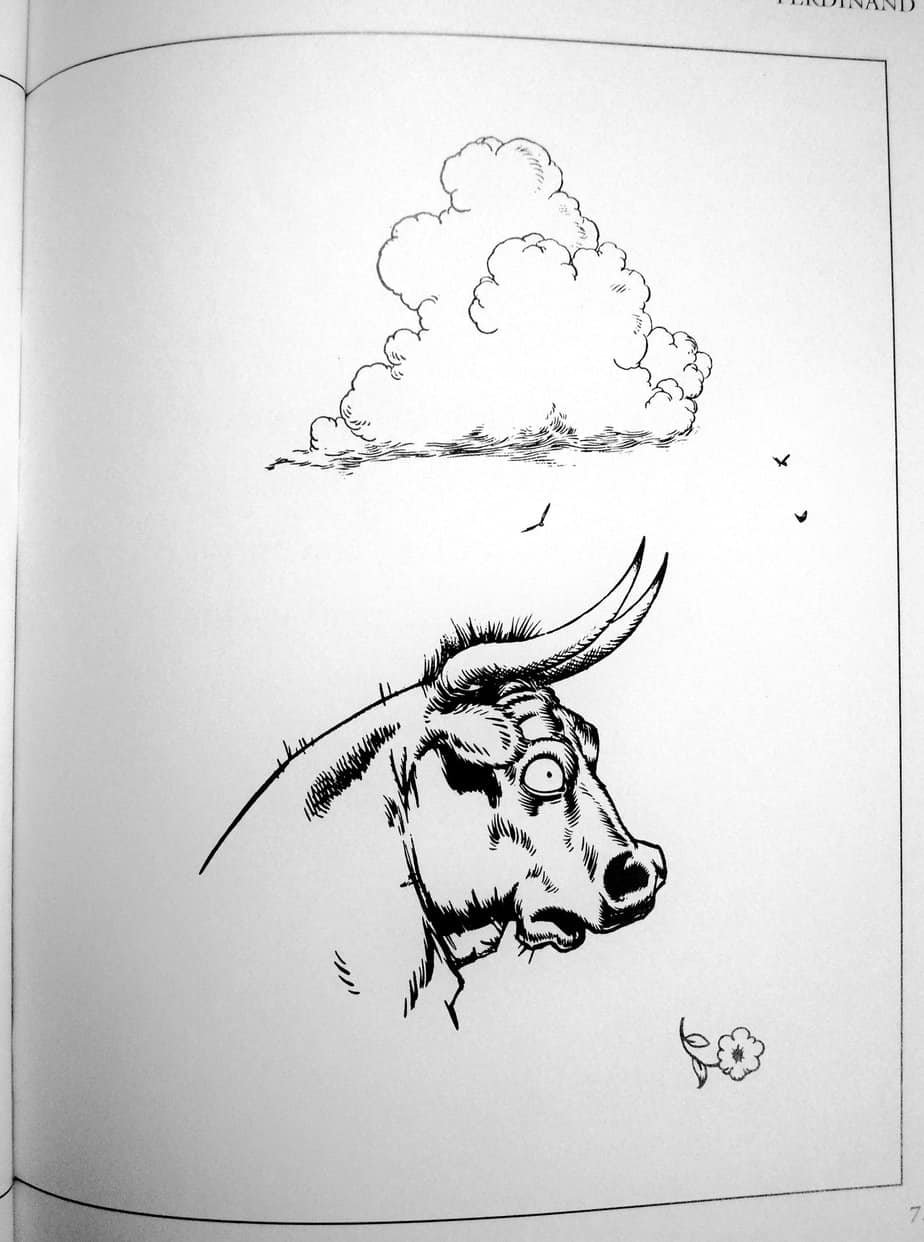

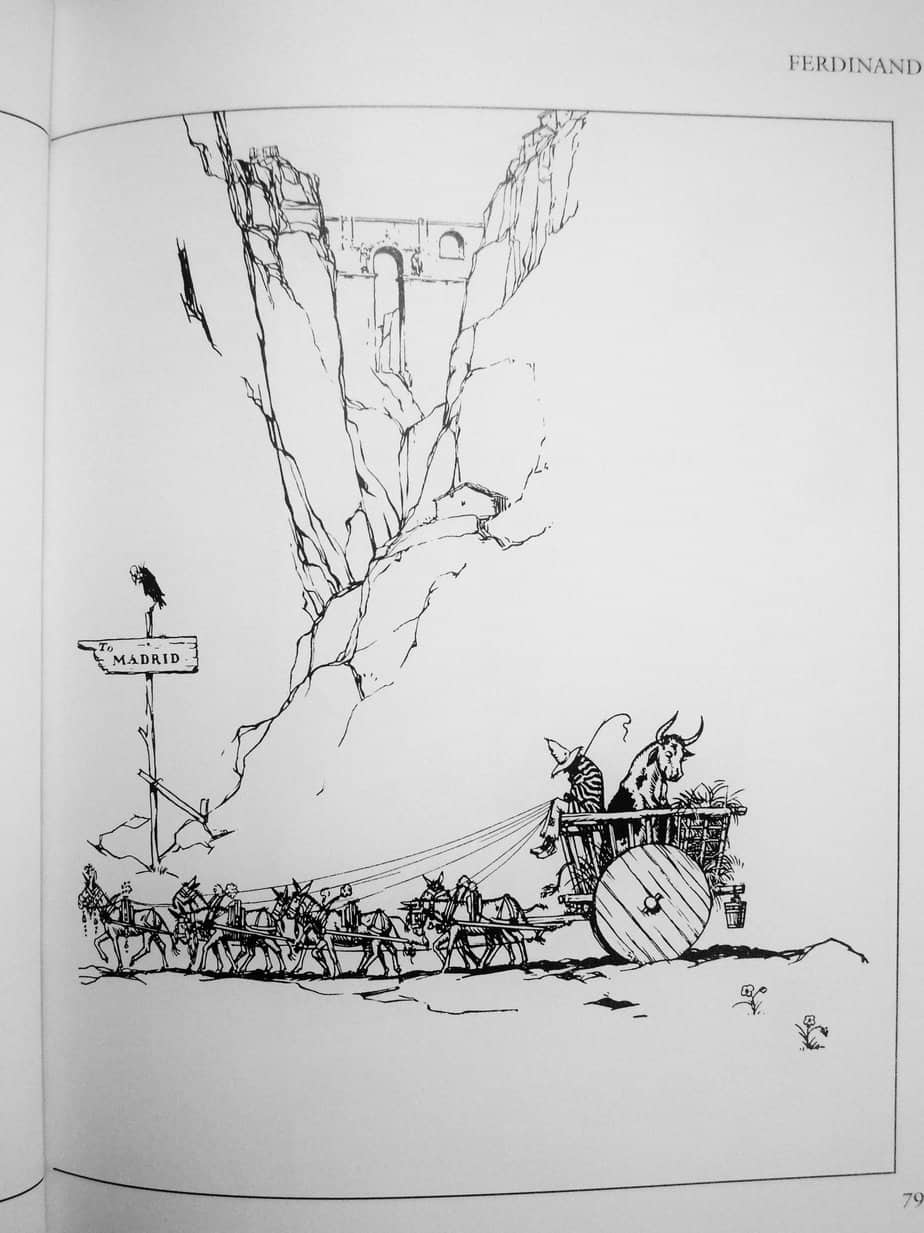

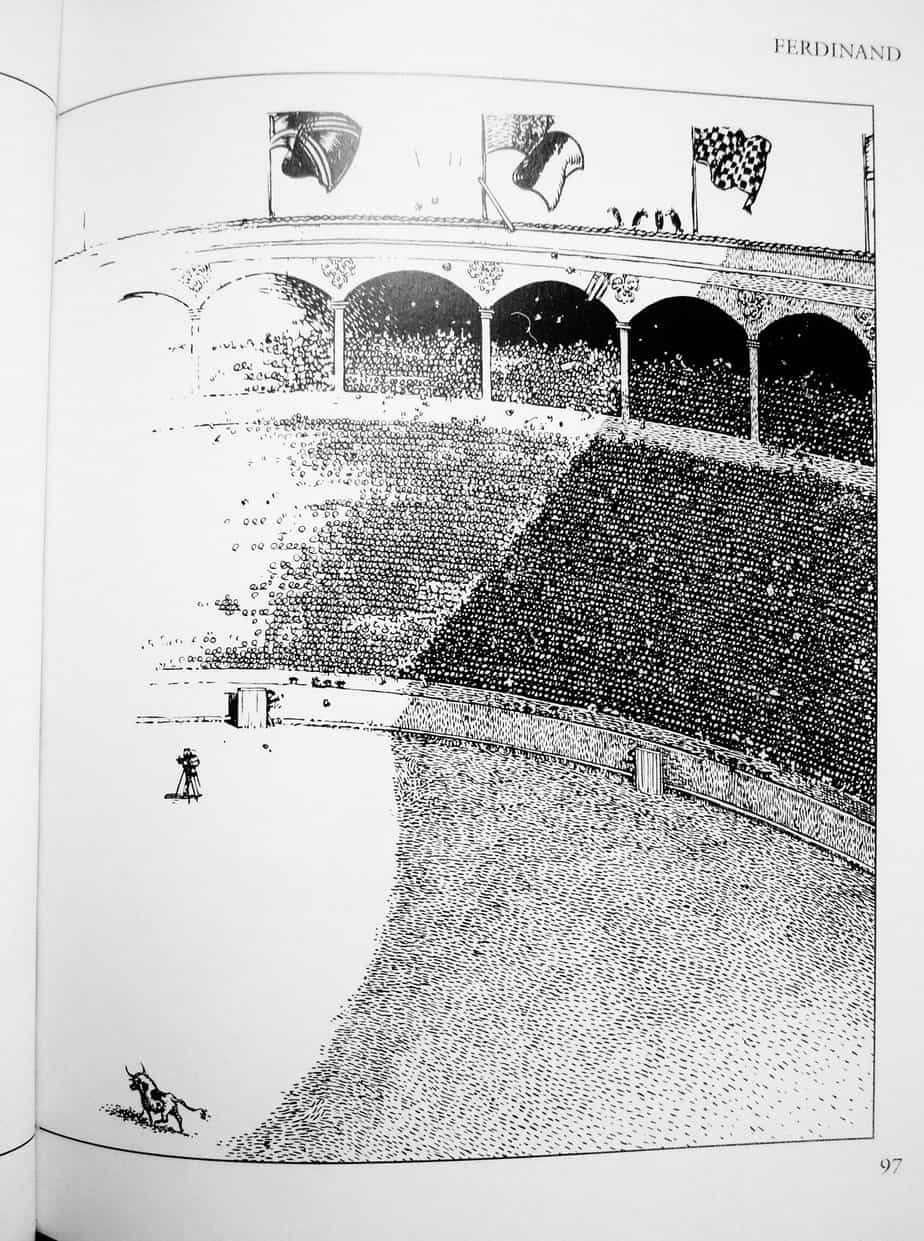

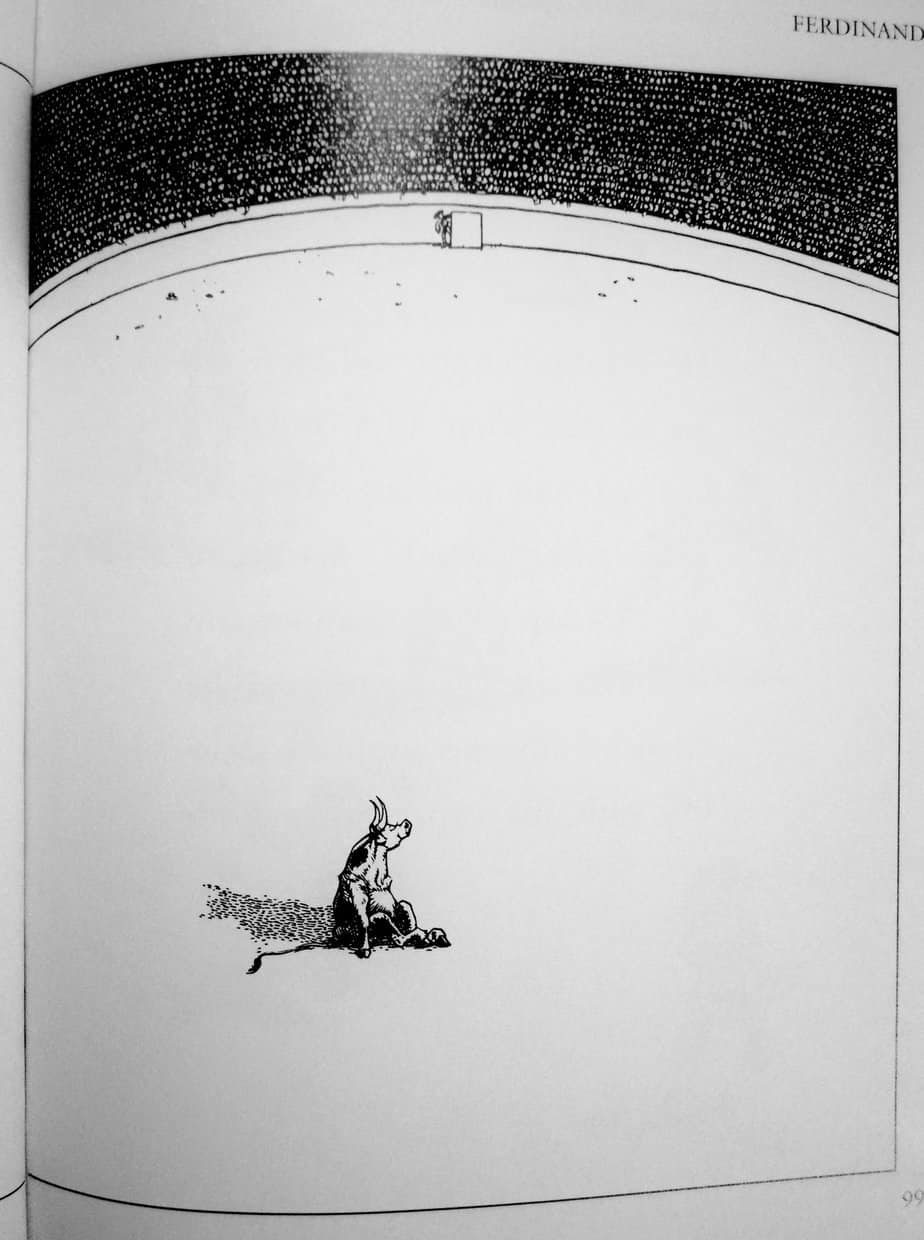

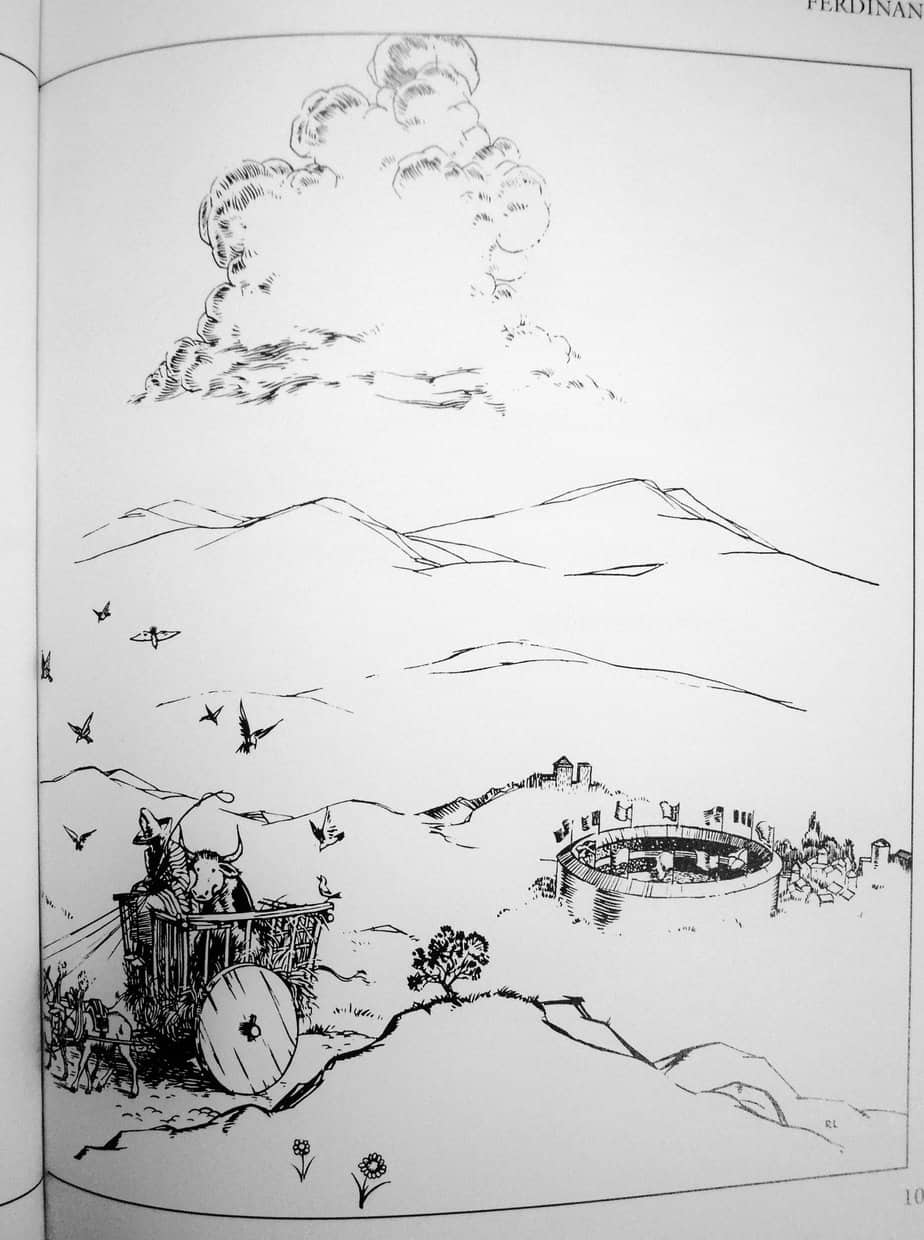

Ferdinand The Bull by Munro Leaf and Robert Lawson may not stand out as remarkable to a contemporary audience, but this picture book is significant for Lawson’s early use of cinematic perspectives. Picture books were influenced by motion pictures and photography in a wide variety of ways. Ferdinand the Bull is a standout example of a picture book which would have looked quite different had the audiences not been visually literate due to movies. Lawson’s use of negative space is also modern and remarkable. The linework is clear, similar to the linework utilised by the atomic illustrators.

There is much to be mined here for the teacher of philsophy. The Story of Ferdinand is explored in detail at the Story Philosophy blog, with example questions for discussion.

SETTING OF THE STORY OF FERDINAND

Some people use bullfights, some the Mass, some art in order to ritualize or transform death into life or at least meaning. But my terror is that life itself is a ritual transforming everything into death.

Marilyn French, The Women’s Room

PERIOD — ‘published in September, 1936, three months after the start of the Spanish Civil War, when Fascist military forces began rebelling against the leftist Republic.’ (The New Yorker)

DURATION — The youth of a bull, culminating in a coming-of-age experience

LOCATION — Spain

ARENA — between the farm and the bullring

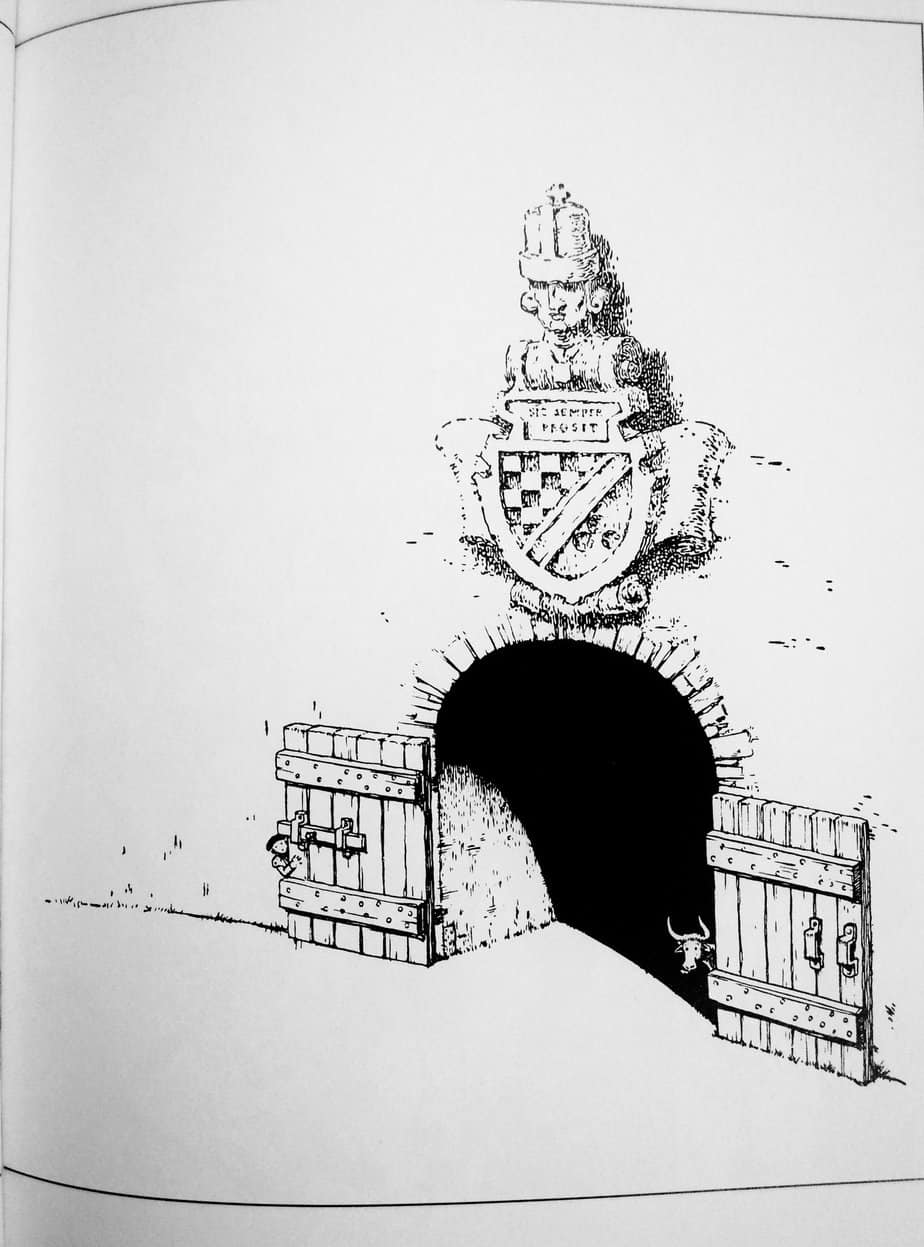

MANMADE SPACES — the bullring

NATURAL SETTINGS — the space under the cork tree

WEATHER — Sunny, pleasant weather prevails

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY — There is no ‘technology’ crucial to this story but there is a custom — the Spanish custom of watching bullfighters in the ring.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT — Although this term wasn’t around in the 1930s, this is about how when little boys begin to look like men, they are expected to fit into the ‘man box’. The engines of patriarchy kick in and if he does not conform, the culture around him will do its best to make him conform, dammit.

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE — Ferdinand himself is not a rounded main character. He is one-dimensional and aloof. Importantly, he is fine just the way he is, from the start of the story until the end. This is therefore not a story about Ferdinand, but the story of a society, and it is the society around Ferdinand who must learn something: That it’s okay not to be tough, aggressive and controlling, even if you are a bull.

The Man Box is the set of beliefs within and across society that place pressure on men to act in a certain way. Our study explored how young men encounter the Man Box rules in society and internalise them personally by asking their views on 17 messages about how a man should behave. These 17 messages were organised under seven pillars of the Man Box which are: self-sufficiency, acting tough, physical attractiveness, rigid gender roles, heterosexuality and homophobia, hypersexuality, and aggression and control.

APO

As I’m sure you can guess, The Story of Ferdinand elicited overt homophobia from many of its critics. Homophobia is interchangeable with femme phobia and is a necessary tool in maintaining a patriarchy.

“Certain irate fathers assert that the book is a deliberate attempt to make mollycoddles out of little boys,” noted a reporter at the New Yorker. ‘Lesser children’s authors’ were thought to now by “forced” into a feminisation of literature, creating characters who played “Cassandra with a lisp”. (In case you hadn’t noticed, whenever someone talks about the feminisation of an industry, they never mean it as a good thing.)

Separately, can we get rid of the word ‘mollycoddle’, and its only slightly less unkind shortening, ‘coddle’? What we really need to get rid of is the entire concept that extending kindness to someone who needs it is a problem, but encouraging disuse of the word will help take us in a kinder direction.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE STORY OF FERDINAND

PARATEXT

Unlike all the other little bulls — who run, jump, and butt their heads together in fights — Ferdinand would rather sit under his favourite cork tree and smell the flowers. And he does just that, until the day a bumblebee and some men from the Madrid bullfights give gentle Ferdinand a chance to be the most ferocious star of the corrida – and the most unexpected kind of hero.

MARKETING COPY

Beloved all over the world for its timeless message of peace, tolerance and the courage to be yourself, this truly classic story has been enchanting readers since its release in 1936.

SHORTCOMING

‘Alone’ characters are often coded as ‘lonely’ by audiences, so Munro Leaf goes out of his way (via the understanding of the loving cow mother) to assure readers that although Ferdinand likes his alone time, he is not in fact lonely.

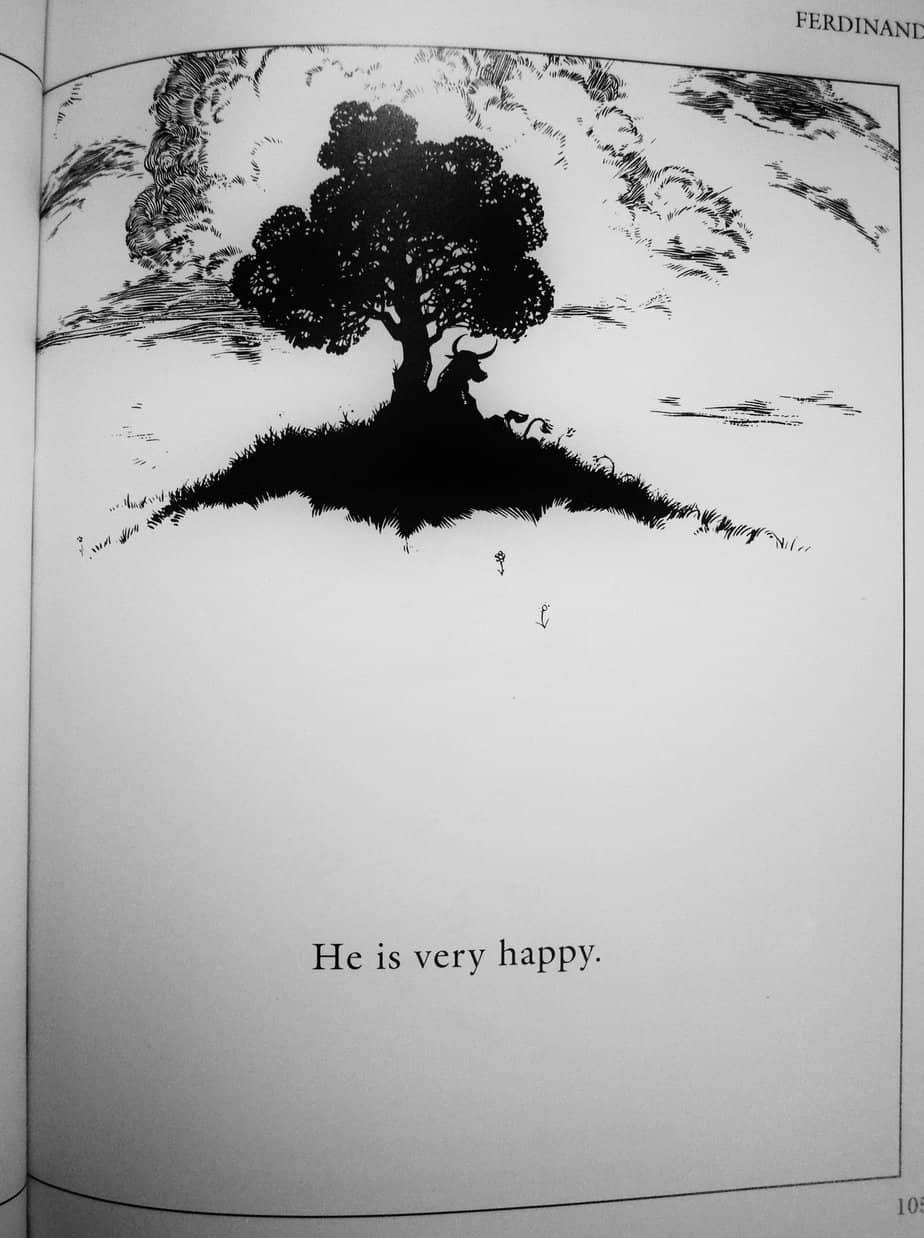

White space is utilised by the illustrator to show how small and alone Ferdinand is. This invokes empathy.

The shortcoming of the community is that accepted variations on masculinity don’t extend as far as ‘pacifist’.

DESIRE

Ferdinand wants everything to stay the same.

OPPONENT

The bee is what I’ll call the ‘McGuffin opponent’ — not the real opponent, but a stand-in, who through no fault of its own sets off a chain of events that work against Ferdinand.

The other opponents are the men who come to the farm and mistake Ferdinand for someone he is not.

Finally, in the ring, the opponents will be the audience (expecting a fight) and the picadors, the banderilleros, and the matador.

PLAN

The plan is driven by the opposition, since Ferdinand has no plan other than to sit under a cork tree and enjoy the smell of flowers.

The bull scouters plan to find a good fighting bull and take him to fight in the ring, so they can provide entertainment to the masses and get rich.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

This story has a natural climax — the bull fight, which is an anticlimax because Ferdinand sits down and smells the flowers in all the lovely ladies’ hats. At this point Ferdinand’s mask comes off and he is revealed to be the opposite of a stereotypical angry, aggressive bull.

ANAGNORISIS

The community realises Ferdinand is not a fighter. More importantly, they realise it’s okay if you’re not like that. They leave Ferdinand to live as his authentic self.

NEW SITUATION

In the story, Ferdinand is returned to his tree after proving a non-fighter.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

In reality, this is not what happens to bulls.

Publisher’s Weekly reported that Munro had received a complaint from a Geneva-based diplomat of undisclosed nationality who pointed out that “the real fate of any little bull who would not fight was a tragic trip to the butcher shop.” The implication was that Munro had dismissed the challenges facing professional peacemakers, and that Ferdinand must be some kind of dupe or quisling.

The New Yorker

(A quisling is a traitor who collaborates with an enemy force occupying their country.)

RESONANCE

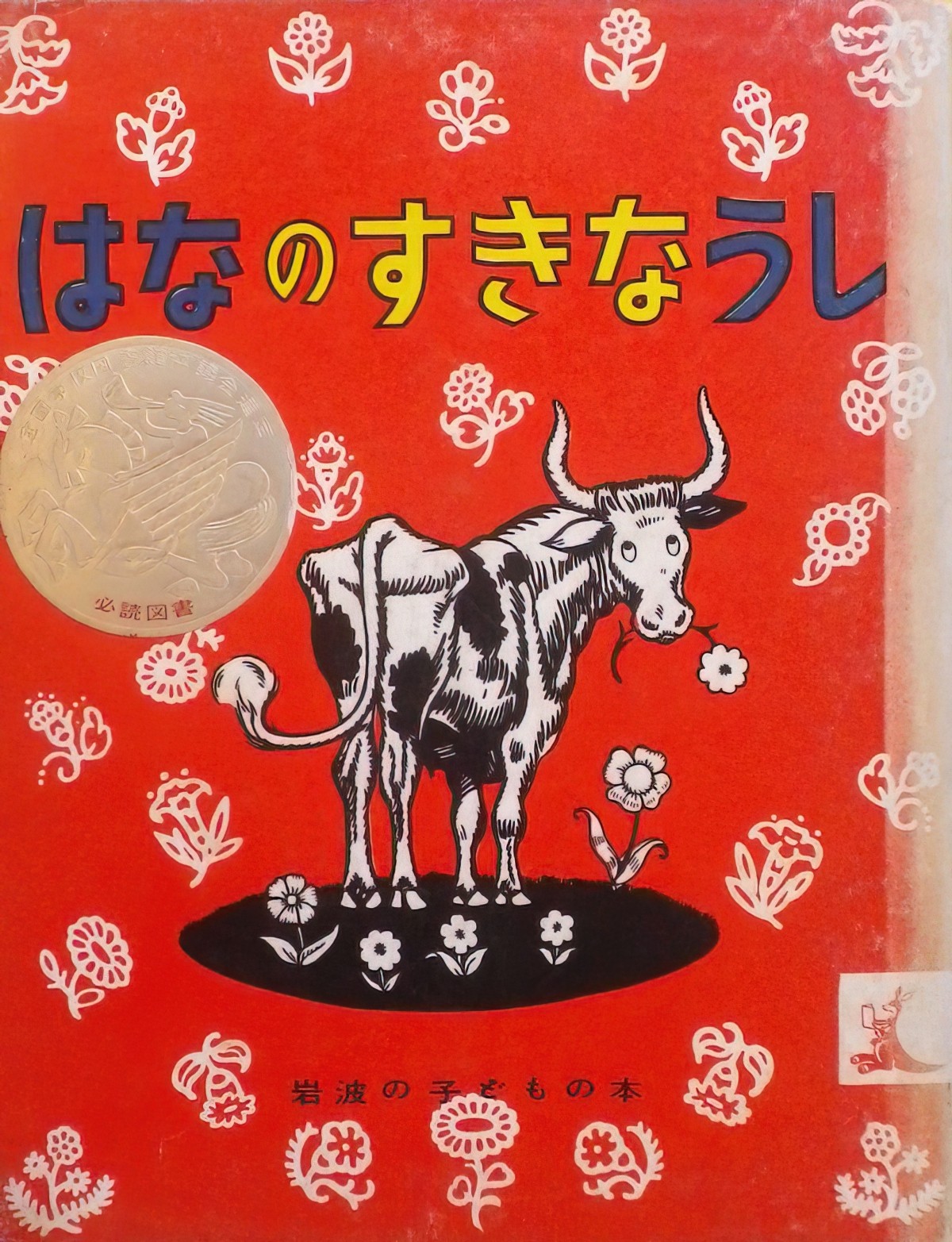

Munro Leaf’s The Story of Ferdinand became a Disney animated film only two years after its publication, winning a 1938 Academy Award.

The Story of Ferdinand sold respectably, at first, moving fourteen thousand copies in its first year. But it took off, in 1937, for reasons no one was quite sure of. By its first anniversary it had sold eighty thousand copies, a phenomenal number for a picture book during the Depression. By that Christmas, as this magazine reported, sales were “running slightly behind Dale Carnegie and well ahead of Eleanor Roosevelt.

The New Yorker

There is a more recent adaptation which is a barely recognisable version of Leaf and Lawson’s original.

At time of publication, adults were arguing about the value and messages of The Story of Ferdinand.

[The Story of Ferdinand] was caught in the culture-war crossfire of its own era. Mahatma Gandhi and Eleanor Roosevelt were on Team Ferdinand. Adolf Hitler and Francisco Franco were not. … Ferdinand’s pacifism conveyed a loaded message if looked at the right, or wrong, way.

The New Yorker

Although Munro Leaf thought he had made a picture book for adults, he eventually realised the universality of Ferdinand’s ideology, and I’m sure it was much needed in an era ravaged by war, in which men would have felt the heavy burden of masculinity weighing heavy on their shoulders, under the propaganda that men can save a country*.

*In case it needs to be said, I don’t believe this myself.

The success of Ferdinand may have had an influence on a new subgenre of picture books:

“Ever since Munro Leaf wrote his story about the mal-adjusted bull, our nurseries have been flooded with pieces about locomotives tired of the track, lambs who have lost their wool,” and so on, a writer for The New Yorker reported in yet another Talk of the Town piece on Ferdinand, with tongue perhaps halfway in cheek.

The New Yorker

Even today, there are many picture books about characters who have the courage to be themselves. This is an excellent thing. There are far fewer encouraging young boys to be pacifist and kind and interested in girly things such as flowers. We still need more of those, even though there are now plenty of books about girl characters doing traditionally boyish things.

FURTHER READING