she considered that ‘pregnant’ and ‘married’ were alternative terms for ‘death.’

Claire Dederer, from ‘Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma’

There’s a very good reason why girls and non-binary children should be told the truth about baby-making as soon as they ask: If she’s old enough to be asking, she’s old enough to be worrying. Unless they’re told exactly how pregnancy happens, young girls often worry that it may happen to them at any time, without warning. The prospect is terrifying.

For people without a womb, it’s perhaps difficult to imagine the terror of becoming impregnated against one’s will, to have a human growing inside, to endure excruciating labour. For those exact reasons, existing reproductive rights must not be lost. Full reproductive rights must be afforded to all.

There are … three specific causes of death that have appeared throughout every era: homicide, childbirth, and malaria.

Most Common Causes of Death During Specific Eras, Laughing SquidUnfortunately, …three killers, which have been on a spree since the dawn of humanity, and have likely dispatched more people than anything else. The first is other humans; childbirth, which has killed more than 5 billion women throughout history…We know from ancient writings and anti-malarial adaptations deep in the human genome that malaria has been killing people since day one.

David Goldenberg of MinuteEarth

For most of human history, the womb-bearers had little to no choice about becoming the receptacles of new life, often at the expense of their own life. The act of giving birth was historically far more dangerous than it is now, at least for many, in many countries around the world. Before giving birth myself, I used to marvel at the nonchalant looks on pregnant women’s faces. How did they look so serene? Why weren’t they terrified? Turns out they probably were, among many other emotions. The terrifying aspect of pregnancy and labour remains largely hidden to those not currently experiencing it. I believe many mothers also forget that terror once it’s safely over (otherwise no one would go back for subsequent rounds).

But the specific terror of pregnancy and childbirth is right there in our collective consciousness, and we only need look at the history of storytelling. We can trace this specifically feminine fear across our mythologies, folk tales and fairytales, right back to antiquity. Women have always been afraid of pregnancy and childbirth. Women have also been afraid of subjugation to men they’re married of too, often without their full (or partial) consent.

Academics have named this natural dread “Fear of Engulfment”. It’s a good name. “Engulfment” is bigger than pregnancy itself. It’s about losing one’s body. When pregnant, you’re literally sharing your own body with someone else. The bifurcation of mother and child is long and slow, especially when breastfeeding. Once you’re a mother or a wife, you share your identity. Especially when sharing air space with your offspring, and historically with your husband, your main role is ‘mother’, no matter what you were before, what you still very much are. “Engulfment” means to be swallowed up in or be immersed by something, which may result in asphyxiation. Becoming a mother can at times feel very much like metaphorical engulfment. During pregnancy and labour, engulfment is literal, not due to asphyxiation, but to the myriad of complications concomitant with human childbirth, which is dangerous.

“The Frog Prince” is the perfect example of a fairytale all about Fear of Engulfment. In fact, it’s about Death by Engulfment. If the girl ends up married at the end (subtext reading: permanently pregnant for the rest of her natural life) then she her ‘fear’ has morphed into ‘death’.

Once the Grimm brothers got hold of these tales, girls told for and by women were changed — sometimes subtly, oftentimes not — to focus on masculine fears and desires. Anyone reading The Frog Princess today might therefore think it was written by patriarchal sympathisers indoctrinating young women into doing as they were told: shut up and marry whichever warty suitor your father chooses for you. No doubt about it, that’s how that tale often reads today, even in modern retellings for children. But that story was undoubtedly created by women for other women, as a way of tapping into their collective terror.

In contrast, the masculine stars of fairytales tend to leave the home, overcome opposition, fight battles and either return home or find a new one of their own.

The death by engulfment plot doesn’t require the feminine star to leave home. This tale is about the psychosexual trauma of being a young woman forced into marriage and childbearing.

“Bluebeard” is another example of a Death by Engulfment tale. “Go with the flow and everything will be all right,” this story tells them now. But in the hands of a feminist (e.g. Angela Carter), the story lets young women know that, if they are terrified of marriage, of entering a new family where there’s no guarantee she’ll be loved or respected, she’s certainly not the first to have experienced that fear.

“Beauty and the Beast” is another example. This traditional belief about how female desire works can be seen in Beauty and the Beast and “Ricky With The Tuft“. In his conclusion of “Ricky With The Tuft”, Charles Perrault specifically explains to the reader that the magic in his story is simply a metaphor for the way women are inclined to fall in love. Though men always seek physical beauty, women look instead for virtue and some kind of essential goodness.

FEAR OF CHILDBIRTH

An unusually deep fear of childbirth is now known as tocophobia. But I wonder if there’s a name for the fear — akin to disgust — of women sharing details of the carnal realities of everything to do with pregnancy and childbirth, including menstruation (still unusually absent in children’s literature, in contrast with the great corpus of middle grade stories about bums, farts and poo).

In the age of the Internet, women are criticised for sharing stories of childbirth online and therefore inducing new tocophobia in other women. Most recently the target of such vitriol was directed at Chrissy Tiegen, but whenever you’re reading this, there is bound to be a more recent example.

We might consider fear of engulfment as a liminal space between girlhood and womanhood — a period of unguarded impulses, savagery and cruelty in sexual love, combined with the desire for security and and protection. People have always been scared around liminal spaces and states, to do with our fear of change.

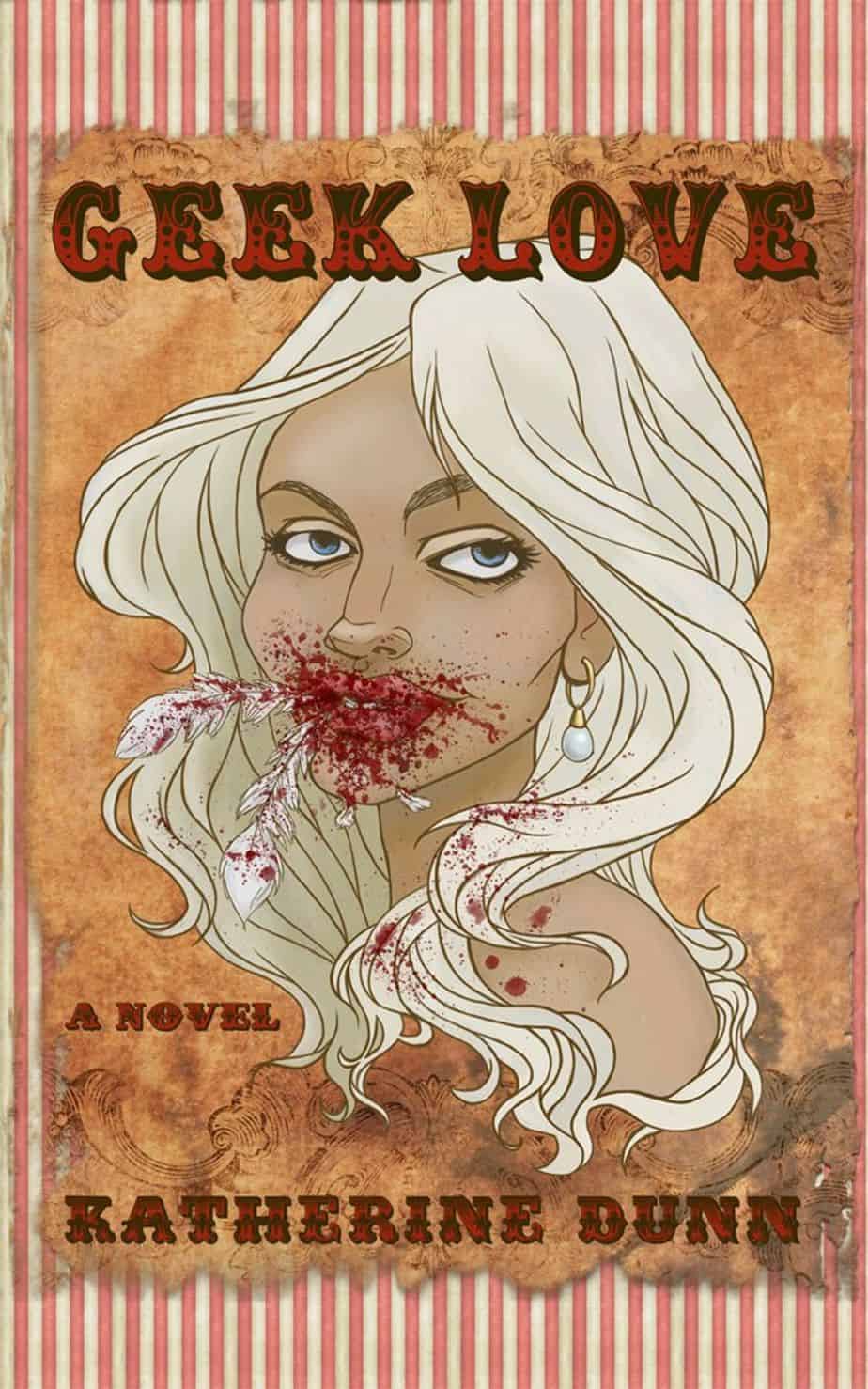

It is the monster that lies across the boundaries of what we might consider to be human; it is through the monster that we encounter definitions of what might be viable human life. The medical profession, of course, is involved with these decisions constantly: in pre-birth diagnosis; at the point of birth, where what has organic coherence and what might be taken to be (ab-jected) as waste material has to be the object of discrimination; and in the contemplation of physical damage and trauma, where what can be saved and what cannot is critical. Teratology is now the monstrous child of medicine, as it used to be the province of witches, seers, oracles, healers of all stripes. Or indeed, of the proprietors of fairgrounds, freak shows, circuses — one of the most remarkable novels relevant here is Katherine Dunn’s Geek Love (1989), which centrally concerns the supply of monsters for display (monsters to be ‘demonstrated’) through the manipulation of drug supply to a pregnant woman.

Weird or What? The Nautical and the Hauntological by David Punter, Fantastika Journal Vol 1, Issue 2, December 2017

Geek Love is the story of the Binewskis, a carny family whose mater- and paterfamilias set out—with the help of amphetamine, arsenic, and radioisotopes—to breed their own exhibit of human oddities. There’s Arturo the Aquaboy, who has flippers for limbs and a megalomaniac ambition worthy of Genghis Khan . . . Iphy and Elly, the lissome Siamese twins . . . albino hunchback Oly, and the outwardly normal Chick, whose mysterious gifts make him the family’s most precious—and dangerous—asset.

As the Binewskis take their act across the backwaters of the U.S., inspiring fanatical devotion and murderous revulsion; as its members conduct their own Machiavellian version of sibling rivalry, Geek Love throws its sulfurous light on our notions of the freakish and the normal, the beautiful and the ugly, the holy and the obscene. Family values will never be the same.

FEAR OF ENGULFMENT IN SHORT STORIES

Katherine Mansfield’s young women are often said to be in this space, afraid of adult relationships, wishing to remain in an emotional state of childlike fantasy.

“Something Childish But Very Natural“, “Taking The Veil” and “Psychology” are excellent examples of how Mansfield explored these specifically feminine fears.

Angela Carter’s short stories make for excellent case studies. Carter makes use of imagery to convey the feeling of engulfment across a story:

[A]nxiety about sexuality and the imagery of engulfment are also combined in [The Bloody Chamber]. This is particularly visible in “The Erl-King” … In the story, the protagonist dwells on her attraction to a fae figured called the Erl-King. The Erl-King captures women who stray into the woods and transforms them into birds that he keeps in cages. Despite this danger, the protagonist allows him to seduce her.

Alex Rouch at BookRiot

FEAR OF ENGULFMENT REIMAGINED AS MYSTICISM

FEAR OF ENGULFMENT IN FILM

The Fear of Engulfment is a strong thread in Into The Forest, a 2015 film starring Ellen Page and Evan Rachel Wood.

It currently scores a lowly 5.8 at IMDb — like any film about specifically female concerns, a large number of male reviewers won’t ‘get’ it.

Humans have always sat uneasily with things that defy easy classification. Even worse: People who easy classification. Trans people today are bearing the brunt of that particular wrath.

Pregnant Women As Anomalies In Narrative

In folk and fairytale, the treatment of childbirth goes two ways:

- Veneration of women for their ability to perform the supreme act of childbearing

- Othering of women for their disgusting childbirth stuff, and the reminder that we are all animals oozing bodily fluids all over the place

First with the veneration examples:

- Powerful women are said to have given birth to the world: Semmersuaq of Inuit lore, Princess Pari in Korea, the sisters in the Acoma Trib’es “Emerging into the Upper World”.

- Etiological tales try to explain how things came about using narrative rather than science. The Japanese archipelego is said to have been birthed (“Izamani and Iganaki”. West Africa has a tale callked “Anansi Gives Nyame a Child”. Australia has “How Playpuses Came to Australia”. All of these ‘births’ are highly unusual and magical. The conceptions of heroes, saviours and warriors are magical (or virginal).

- Birth motifs can function as a metaphor for anagnorisis (spiritual/emotional awakening and self-revelations).

There wasn’t one linear progression from etiological birthings of everything to veneration of women as mothers to patriarchal suppression. In between the etiological birthings and veneration tales we have a whole heap of stories in which women are entirely passive, almost non-existent during the whole ordeal.

“Perceforest” is a medieval take on “Sleeping Beauty“. In that tale, Zelladine is raped while asleep. She only wakes up when her newborn sucks on her finger, which removes the splinter that put her to sleep.

“Sun, Moon and Talia” from Italy is similar. The version in The Tale of Tales (1634-36), called Lo cunto de le cunti, the plot is almost the same, except the rape ends with the birth of twins.

This started to change by the late 1600s, tales show a shift from disempowerment and passivity to veneration of mothers.

Now we’ve got veneration of pregnant women out of the way, let’s look at the nasty underbelly of birthing narratives.

Removal of mothers from a story is usually good for plotting purposes.That applies in modern children’s stories as much as it always did in folktales. When a mother dies (often in childbirth, let’s face it), that paves the way for a shakedown in power. Once a mother is gone from a family, the pillar has gone. Now there’s plenty of opportunity for juicy narratives about sibling rivalry, evil stepmothers and downtrodden survivors. (Find all of them in Cinderella.)

ARE WOMEN ACTIVE IN BIRTH OR NOT?

Depends if something went wrong.

When there is something wrong with a child, the mother is often blamed for doing something wrong to have caused it, ironically giving mothers a very active role in child-creation when mothers are most often considered passive (but only when things go right). An example of a mother doing something wrong: In the Indian tale “Prince Half-a-son” a childless queen only eats some of the magical potion she was supposed to take for infertility. (Always finish your course of antibiotics, people.) So she gives birth to half a son. In the end though, the half-formed son has the last laugh, rising up above everyone, becoming king etc. (In this version the magical potion is a mango, and the Queen eats half because a mouse has nibbled the other half.)

There are also many fairy tales in which the pregnant woman succumbs to cravings and ruins her child’s life. An example is a version Rapunzel, in which Rapunzel’s mother sneaks into a witch’s garden to eat some parsley type stuff. The witch catches her in the act and demands the baby for her own once it’s born.

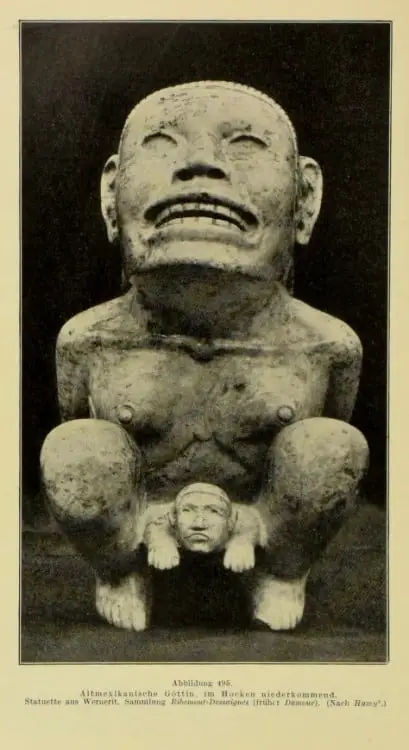

THE PREGNANT WOMAN AS CHIMERA

French psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva has pointed out that pregnant women have across history provoked unease. If a woman is pregnant with a boy she is considered part woman, part man. (And until she gives birth, no one knows she is not part man.) The uneasy symbolism around pregnant women is multivalent: Her foetus is sort of half alive, half not yet alive (ie. dead). So what is she, really? Who is growing inside her? The terror of ‘What’s inside me?’ is explored in the cult classic film Rosemary’s Baby, in which a woman gives birth to the devil.

These may be society’s judgments and a pregnant woman would be better off ignoring them. But judgments of the dominant culture become internalised. Imagine how difficult it is to grow up with this kind of symbolism, this fear of foetuses… and then to become pregnant yourself. Across history, this is exactly the position women have found themselves in.

Then there’s the unavoidable fact that perinatal maternal mortality has until very recently been high. Historically, death by childbirth was one very common way for a woman to lose her life.

THE PREGNANT WOMAN AS CANNIBAL

Unless you’ve had a basic education in anatomy, a pregnant woman appears to have simply eaten a lot. No surprise, perhaps, that antiquity offers a panoply of stories about mothers who eat their children, or old women (witches) who eat children. Women and big stomachs together, right? Also, if a human comes out of a woman, how did it get in there? I can sort of see how pregnant women became associated with cannibalism.

The cannibal is a subject in a gendered plot in which cunning and high spirits win the day, and the boy’s own variety has eclipsed the girl’s in such stories’ transmission since the seventeenth century. Tales of the ‘Beauty and the Beast‘ cycle menace their heroines with death by engulfment, and this obliteration, where a woman’s body is in question, often means sex or childbirth.

No Go The Bogeyman, Marina Warner

Presenting pregnant women as cannibals is just one example of how procreation is presented across history as something dreadful.

THE PREGNANT WOMAN AS TWO-FACED

Another example is the presentation of pregnant women as ‘two-faced’. Sure, women give birth. Great. But birth inevitably ends in death.

Kristeva, who is famous for her 1982 work on abjection, talks about the theme of the two-faced mother in 20th century literature, talks about how the ‘theme of the two-faced mother’ who ‘is perhaps the representation of the baleful power of women to bestow mortal life’.

Probably just as well mothers were largely absent in the Gothic tradition, then. The (non-feminine) Gothic stories were big on death, but said hardly anything about where people came from — that was just too monstrous.

However, mothers started to appear in neo-Gothic fiction over the 20th century. The first appearances of mothers in Gothic texts were monstrous, of course.

BIRTH STORIES AND VIOLENT STORIES

I have noted that in many stories, whether old or modern, battle scenes are often ‘misplaced’. By that I mean, sometimes the storyteller doesn’t give us the blood and gore at the ‘real’ battle (the psychological one) because the plot offers a chance to convey blood and gore somewhere nearby. The audience subconsciously links the on-the-page battle to a deeper, psychological one.

An example of a story where this happens is Hud. This story is about the battle for power between a father and two sons. It’s basically a fairytale in its structure and speaks to an age-old issue: At what point should the patriarch of a family stand down? Are there situations in which he should not? Particularly if you read the film rather than read McMurtry’s novel, there is a series of battles, including one involving pigs at a local event, which on the surface have nothing to do with the battle between father and son.

Like psychological battles, storytellers leave the ‘gore’ of childbirth off the page. It’s just too much, and just too hard. Too confronting. Sometimes, to be fair, a realistic birthing scene doesn’t fit a story’s aesthetic. That is why, in many stories about the battle of childbirth, there will be a symbolic blood scene or a symbolic fight, and the reader links the two. Not everyone has studied symbolism and metaphor in English class; this all happens at a subconscious level, much like a dream.

In the opening to “The Juniper Tree” (collected by the Grimms), an infertile woman cuts her finger. Blood falls upon new snow, establishing a clear link between blood and birthing.

In some of Marie-Catherine Le Jumel de Barneville, Baroness d’Aulnoy’s literary fairytales, pregnant women are locked inside towers or tormented by evil fairies. See “The Beneficient Frog” and “The Spring Princess“.

Modern Witches’ Veneration of Pregnancy

The witch of Hansel and Gretel is an evil cannibal, and their mother (or step-mother) who casts them out due to lack of food is almost as bad. No surprise, then, that modern witches would like to recast the fertile female body as valuable and venerated.

But are they going the right way about it?

In her book The Witch in History: Early modern and twentieth-century representations, Diane Purkiss talks about the “glowing accounts of female altruism” in the corpus of witch reading material. Feminist witches have noted that women have been positioned as “vessels, containers, receptacles, carriers, shrines, shelters, houses, nurturers, incubators, holders, enfolders, listeners”. Witches would like to remind everyone that women are powerful and active.

However, many witches also “celebrate receptiveness as an innately feminine characteristic linked to the biological processes of conception, pregnancy and childbirth.” Purkiss notes that this veneration excludes infertile women, and women who do not wish to become mothers. If Purkiss’s book were published today, it may well mention that this essentialist notion of femininity also excludes trans women, and is complicated by trans men, who sometimes give birth. Purkiss likens the modern witches’ “sanitised and sugary” accounts as women as beautiful lifegivers to the cult of the Virgin Mary.

Conversely, leaders who are also mothers (Hillary Clinton, Benazir Butto) are not generally considered truly feminine, so giving birth doesn’t really help anyone achieve genuine power. More lately we have the example of New Zealand’s Labour Prime Minster Jacinda Ardern, who gave birth as PM. Ardern may shift retrograde thinkers towards a more genuine and realistic notion of what powerful womanhood looks like.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Compared to the amount of folklore surrounding death customs and beliefs, there is little discussion about the beginning of our timelines – the traditions relating to pregnancy and birth. Redressing the balance, on this episode of The Folklore Podcast host Mark Norman is joined by Jemma Nicholls, a doula who has recently begun developing workshops looking specifically at these traditions and customs. Jemma has been researching these areas for some time, leading to the putting together of her new workshop entitled Charms and Childbirth.

REFERENCES

- Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folk Lore and Fairytales

- No Go The Bogeyman, Marina Warner

- The Witch in History: Early modern and twentieth-century representations, Diane Purkiss

In Pregnancy in the Victorian Novel (Ohio State University Press, 2023), Livia Arndal Woods traces the connections between literary treatments of pregnancy and the medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth occurring over the nineteenth century. In the first book-length study of the topic, Woods uses the problem of pregnancy in the Victorian novel (in which pregnancy is treated modestly as a rule and only rarely as an embodied experience) to advocate for “somatic reading,” a practice attuned to impressions of the body on the page and in our own messy lived experiences.

Examining works by Emily Brontë, Charlotte Mary Yonge, Anthony Trollope, George Eliot, Thomas Hardy, and others, Woods considers instances of pregnancy tied to representations of immodesty, poverty, and medical diagnosis. These representations, Woods argues, should be understood in the arc of Anglo-American modernity and its aftershocks, connecting back to early modern witch trials and forward to the criminalization of women for pregnancy outcomes in twenty-first-century America. Ultimately, she makes the case that by clearing space for the personal and anecdotal in scholarship, somatic reading helps us analyze with uncertainty rather than against it and allows for relevant textual interpretation.

Livia Arndal Woods

Oct 18, 2023

Pregnancy in the Victorian Novel