Across children’s literature, young readers see less of mothers than they do in real life, and, as a type of wish fulfilment, many see more interaction with fictional fathers.

Fathers in fairy tales are often absent, such as in Cinderella where he is away on business and then dies. Where fairy tale fathers differ most from mothers is their apparent absent dependability. Fathers can be busy elsewhere but their love remains unquestioned. Mothers, on the other hand, are expected to be present and active and therefore more fallible and open to criticism.

Disenchanted: Disney attempts to break stereotypes of motherhood only to reinforce them by Vanessa Marr

THE FATHERLY IDEAL

Historian Bernard Wishy has noted that as paternal rule in the New England household faded in reality, it flourished a good while longer in story and myth. In popular advice books for parents of the 1830s written by Jacob Abbott, Samuel Goodrich, and others, “it was the mothers who were at the centre of home life, [but] in books for children written by the same authors, the father was clearly in control of the family. This difference,” according to Wishy, “is not surprising for it had not been decreed that the mother formally replace the father. She had, for the sake of practicality, stepped into roles in the nurture literature that the American father could not play well.” Under the new regime, not least of the mother’s primary duties was “to teach the child that he owed supreme respect, love and obedience to his father.”

Minders of Make-Believe by Leonard S. Marcus

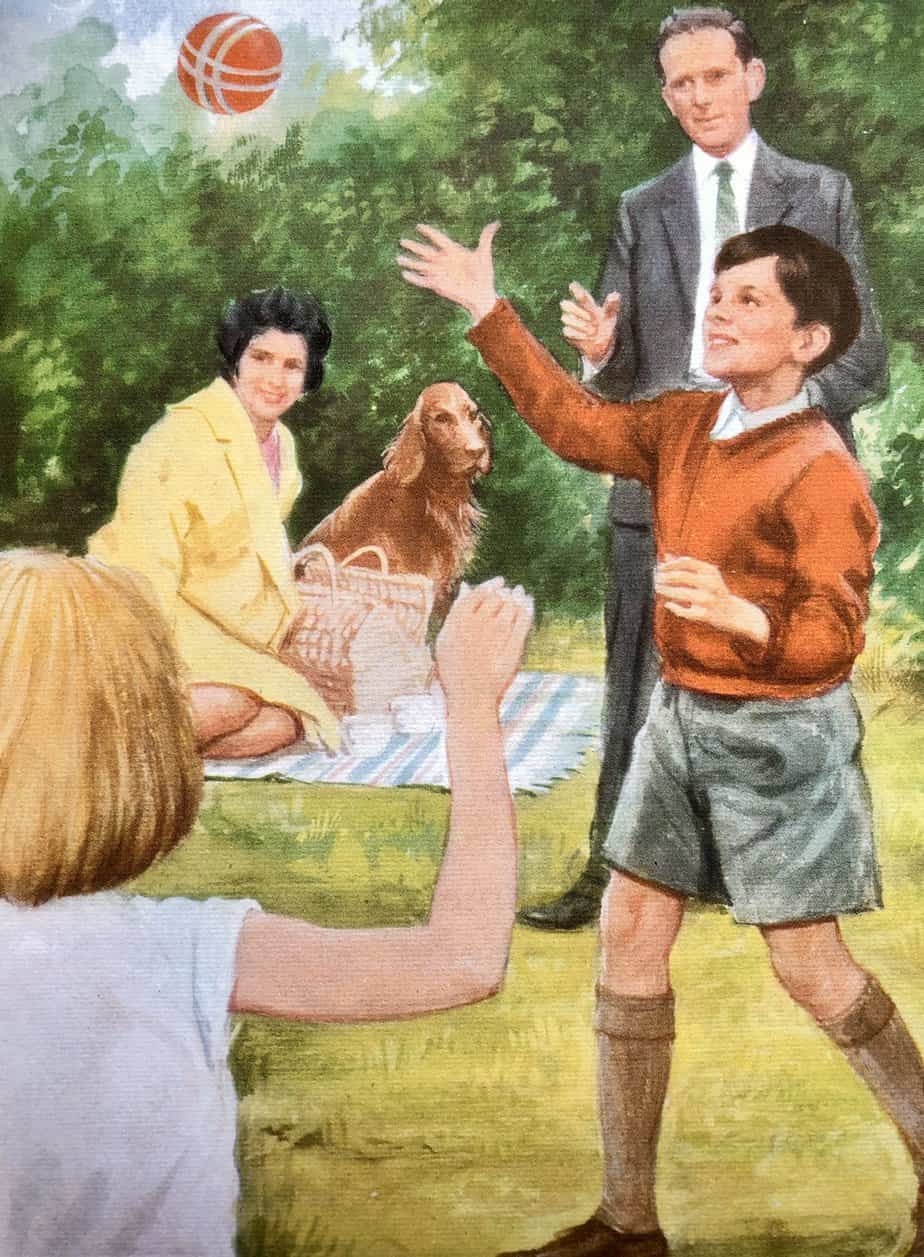

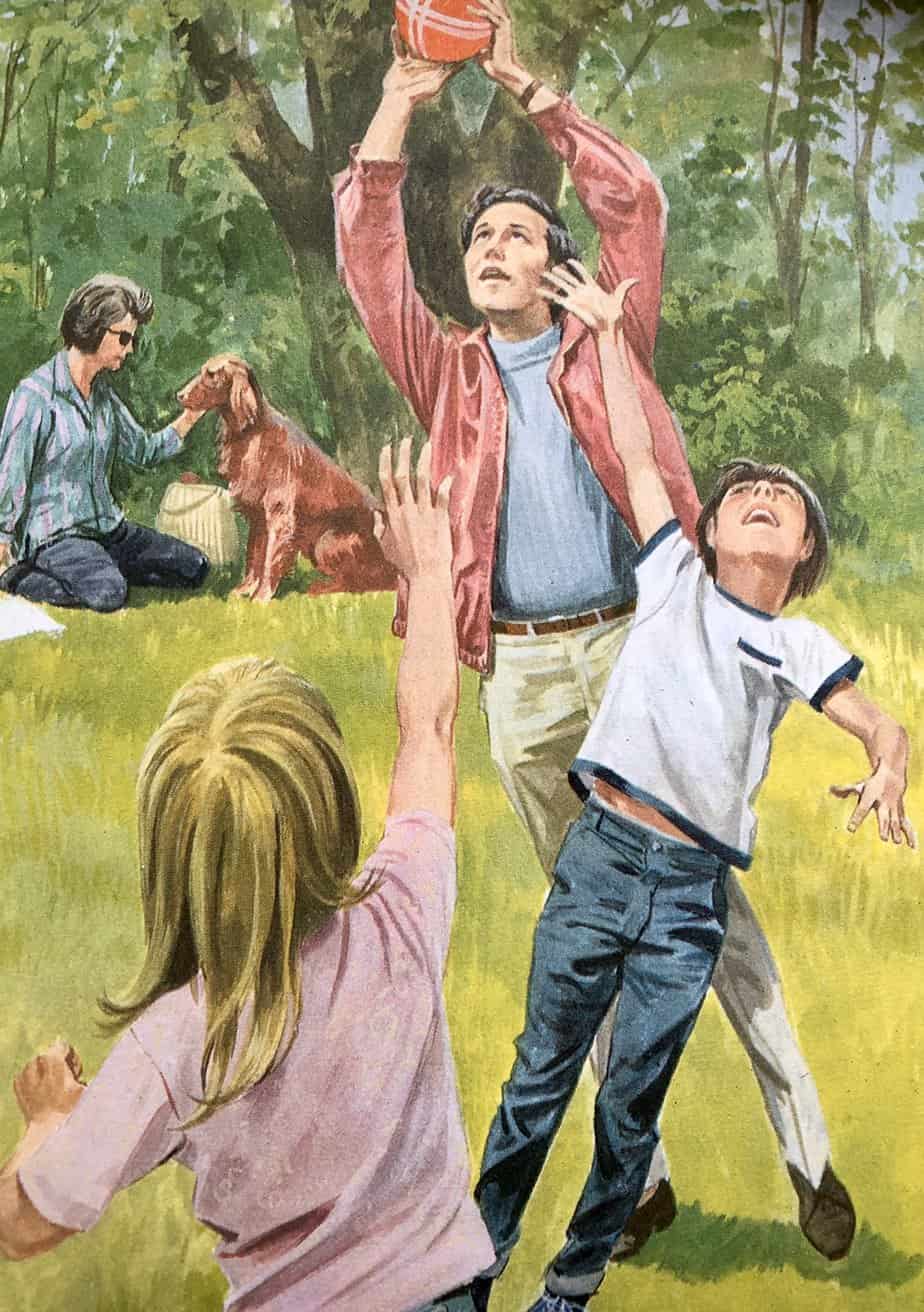

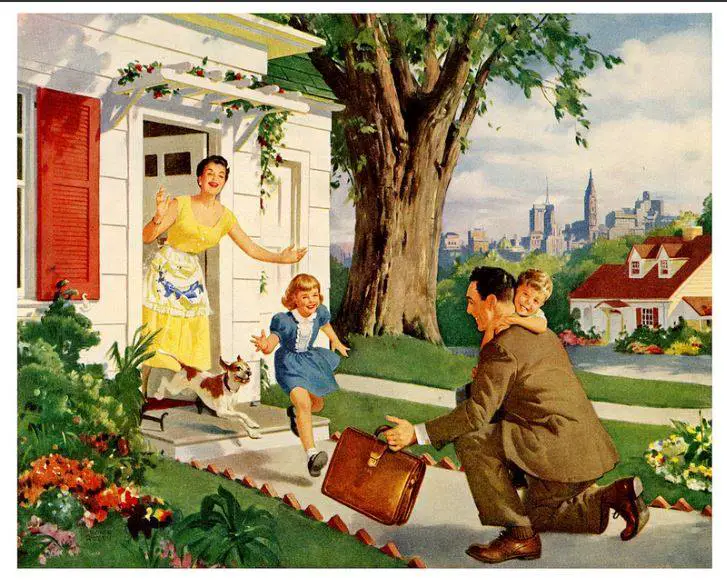

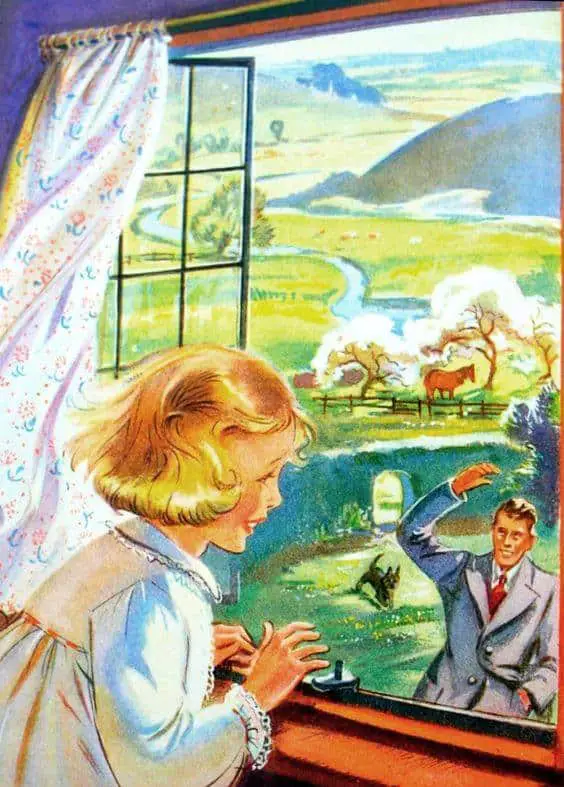

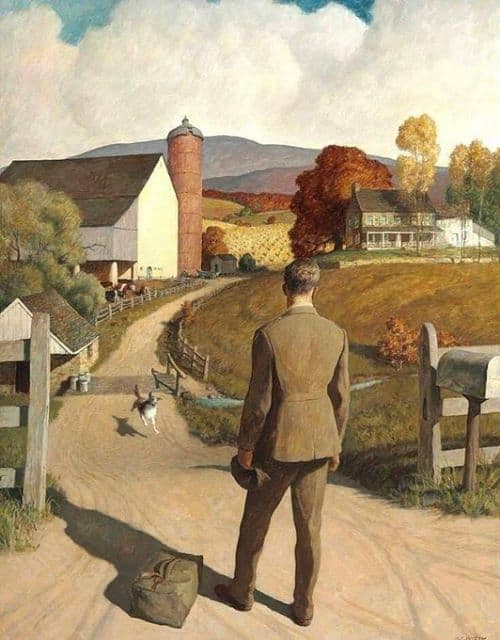

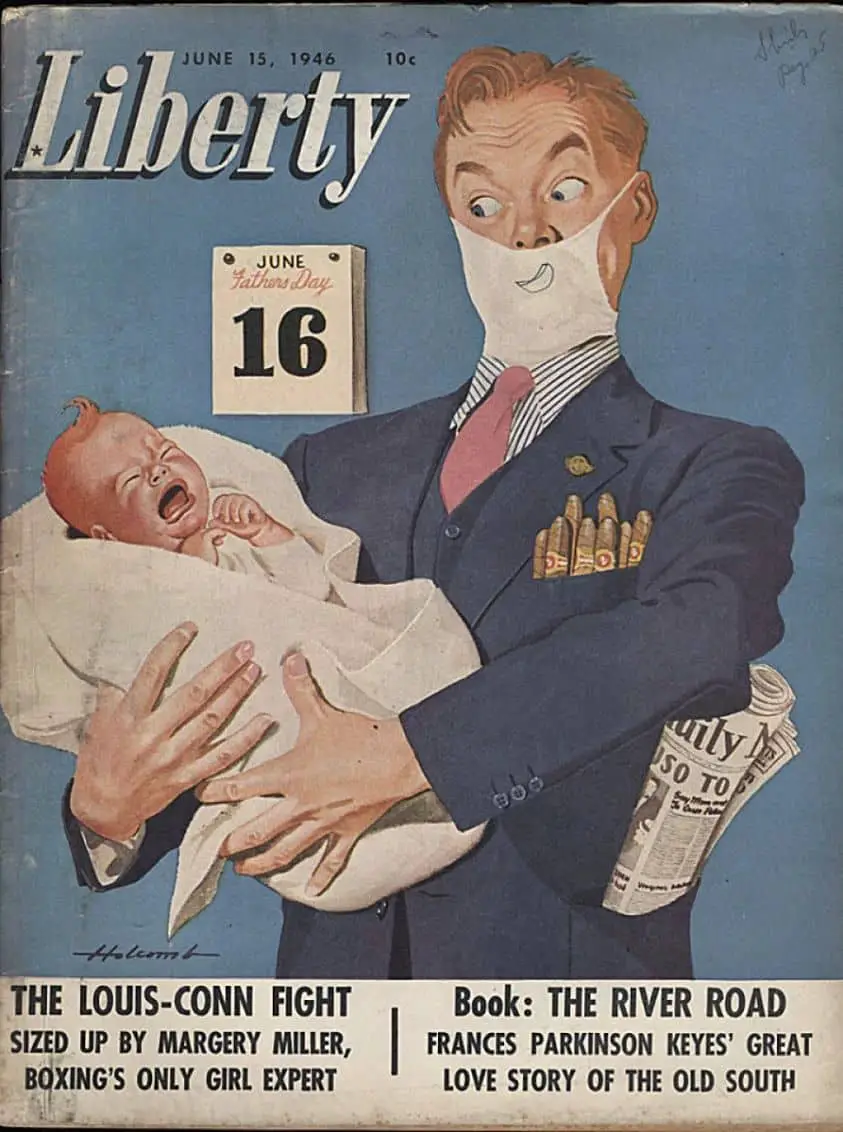

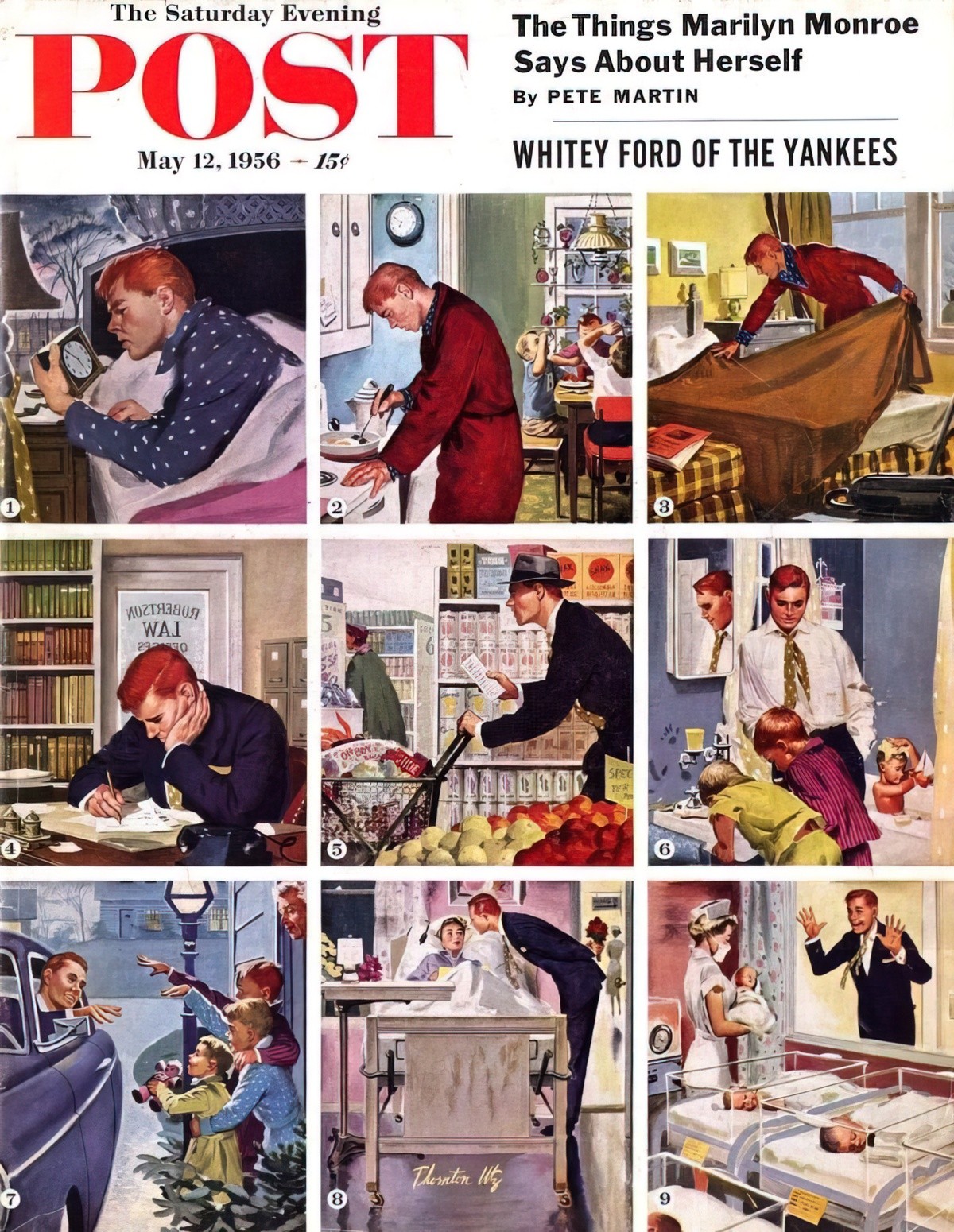

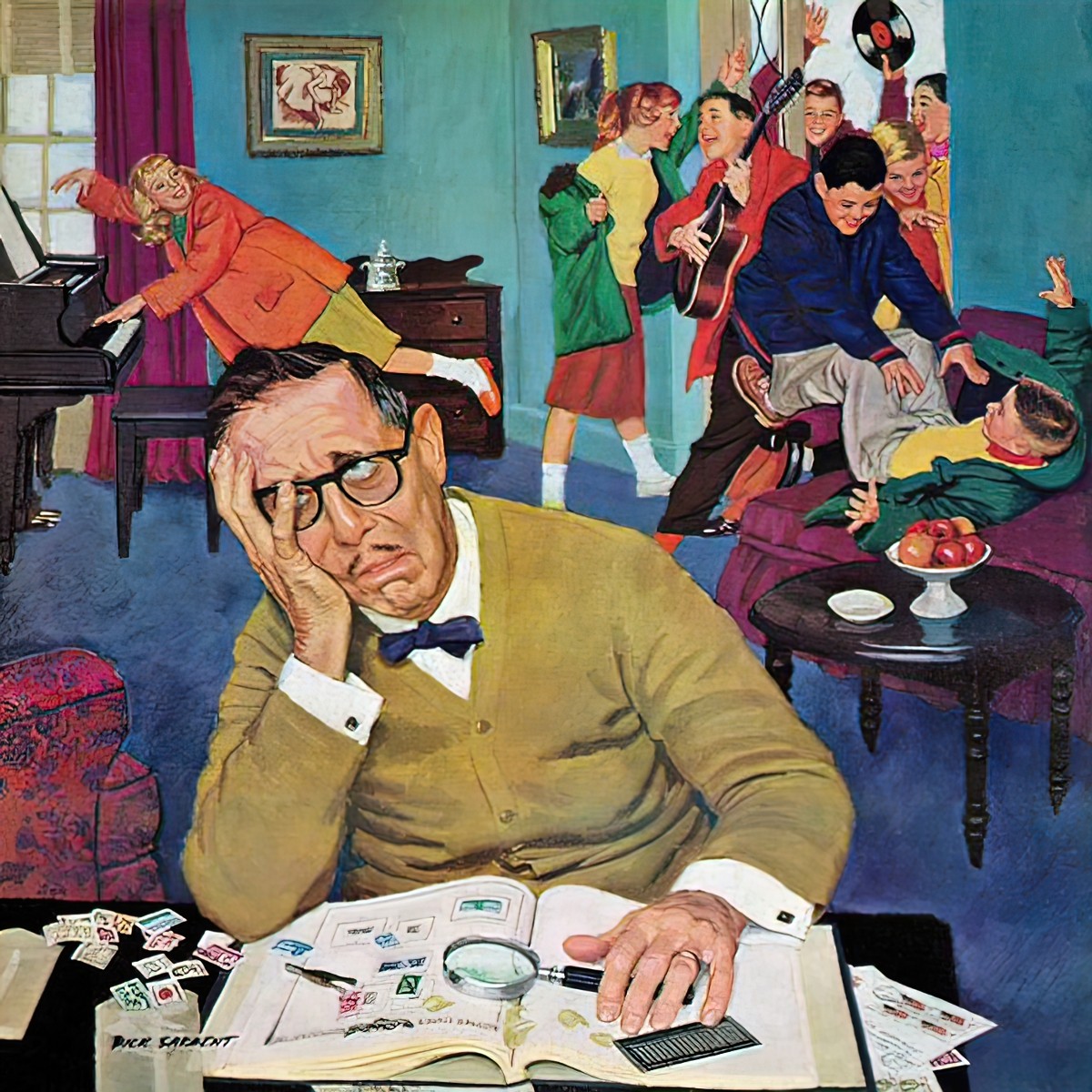

The father who goes to work (during daylight), then comes home to protect his family overnight was the middle class ideal. The city in the background of the 1952 illustration below suggests the father commutes and earns a big wage, returning to the utopian cottage or suburb each evening.

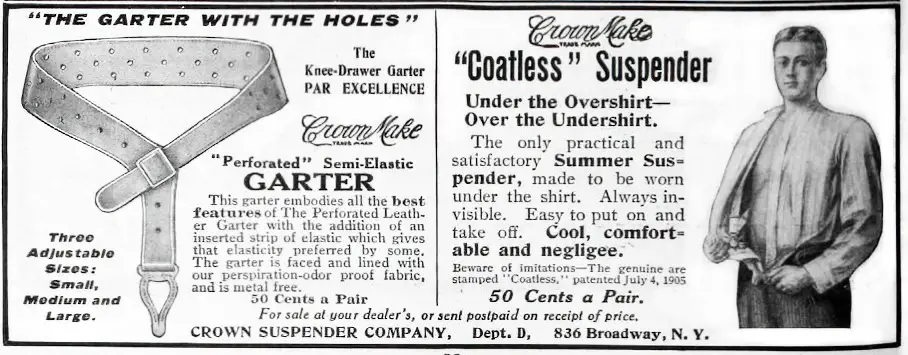

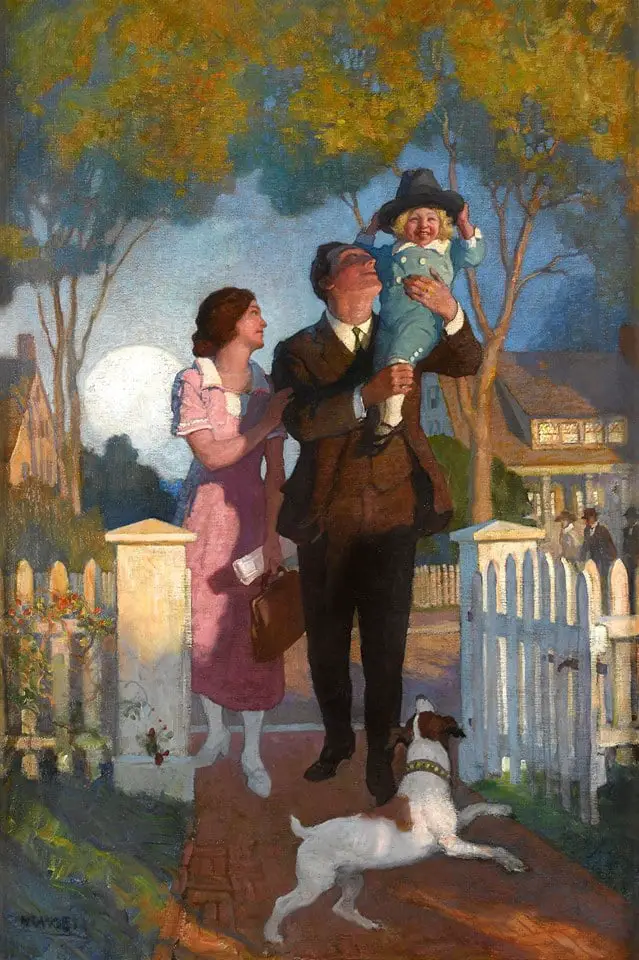

If anyone’s in any doubt about the image of father as protector, take the illustration below, which is selling insurance.

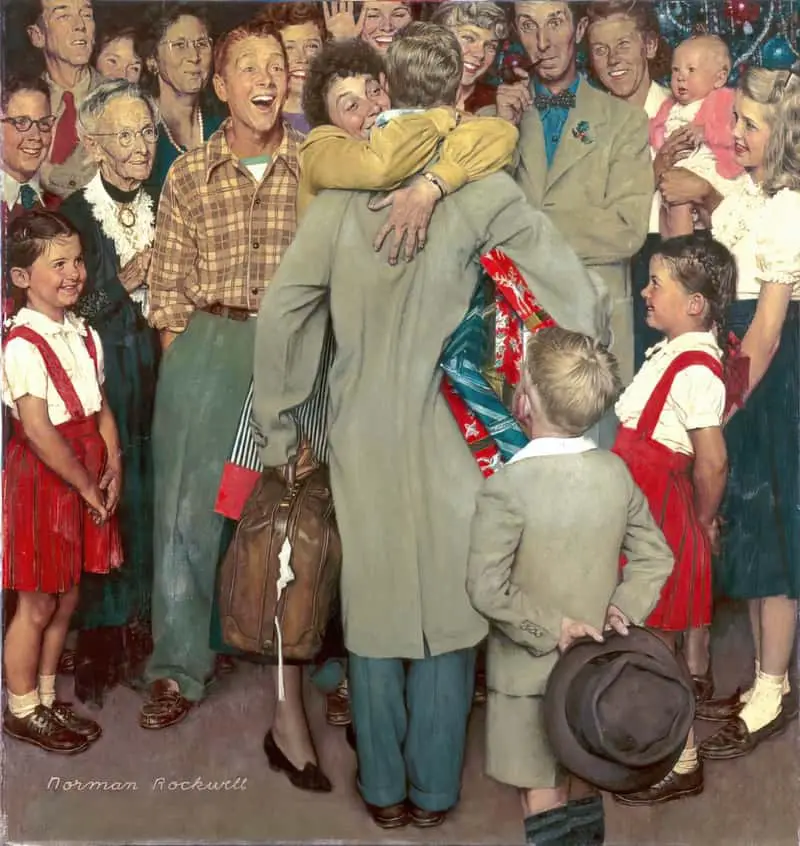

And here’s the father saying goodbye to the son.

TERRIBLE FATHERS

A case could be made that there are already plenty of flawed parents in young adult literature. Richie, from Rainbow Rowell’s Eleanor and Park immediately comes to mind. Is there a more despised character in YA? For me, no.

Bryan Bliss

‘I hate him,’ Eleanor would say.

from Eleanor and Park

‘I hate him so much I wish he was dead,’ Maisie would answer.

‘I hope he falls off a ladder at work.’

‘I hope he gets hit by a truck.’

‘A garbage truck.’

‘Yeah,’ Maisie would say, gritting her teeth, ‘and all the garbage will fall on his dead body.’

Fathers In Picturebooks

It’s common for a young boy in a picture book to want to impress his father. This can even drive the plot, forming the ‘Desire’ part of the story structure (Desires to prove himself to his father).

Examples are the Spot books by Eric Hill and some of the Dr Seuss books — notably his first, And To Think I Saw It On Mulberry Street, in which a boy tries to impress his father by concocting an interesting story about what he saw on the way to school:

When I leave home to walk to school,

Dad always says to me,

“Marco, keep your eyelids up

And see what you can see.”

This desire line feels to me like a specifically masculine one; I can’t easily think of picture books (or even stories for older children) in which a boy or a girl must prove themselves to their mother. In storybook world, a mother’s unconditional love is taken for granted whereas that of a father must be hard won.

Fathers In Fairytales

‘There is hardly a tale in the Grimms’ collection‘ — argued the Grimm scholar and fairy-tale activist Jack Zipes, in 1995 — ‘that does not raise the issue of parental oppression.‘ And yet, ‘we rarely talk about how the miller’s daughter is forced by her father into a terrible situation of spinning straw into gold, or how Rapunzel is locked up by her foster mother and maltreated just as children are often locked up in closets and abused today.’

Frances Spufford, The Child That Books Built

Fathers and Disney Fairytale Adaptations

“My Heart Belongs To Daddy”: Fathers, Bad Boys, and Disney Princesses

Fatherhood is a powerful force in Disney Princess films. Fathers bequeath nobility and exert influence over their daughters, whose marriages often effect the reproduction of economic capital. Even when the fathers of Princesses are absent, as in Snow White, Cinderella, and The Princess and the Frog, they instigate storylines: Snow White’s and Cinderella’s fathers marry cruel stepmothers, setting in train narratives in which the monstrous feminine is central. Angela Carter describes this scheme in her story “Ashputtle or The Mother’s Ghost,” where she reflects that in “Aschenputtel,” the Grimms’ version of the Cinderella story, the father is “the unmoved mover, the unseen organising principle, like God.” In The Princess and the Frog, Tiana’s father has died by the time the story begins, but not before impressing upon Tiana the imperative of hard work, which, he promises, will enable her to “do anything you set your mind to.” Disney’s Sleeping Beauty features two fathers: Aurora’s father King Stegan and his friend King Hubert, who arrange the betrothal of Aurora to Prince Phillip, Hubert’s son. While the Sleeping Beauty scenario comprises the most explicit reference to practices of dynastic marriage in aristocratic families, all the Princess films strenuously advocate heterosexual romance and (with the exception of Pocahontas) marriage, so arguing for the maintenance of “traditional” social and economic orders.

from The Disney Middle Ages: A Fairy-Tale and Fantasy Past by Tison Pugh, Susan Aronstein

Fathers And Domestic Work

There is much to be said about mothers in children’s literature. While authors try to get adult figures out of the way so children can solve their own problems, if there is a parent hanging around the house, it is usually the mother.

Although, arguably, social roles are changing and in more and more households domestic work, including food provisioning, is being shared, cultural change is slow. Vincent Duindam, citing the work of Dr. Morgan, confirms that most of the evidence shows that there are “very slow changes in the direction of men’s participation” in domestic duties and child care and this is supported by the lack of male figures performing these roles in children’s books. In the conservative world of children’s literature it is the female, rather than the male, in general, who is still linked to the domestic.

Carolyn Daniel, Voracious Children

Absent Fathers

Where the father is absent from a children’s story, no matter how terrible he was, the child character often longs for him. (The same is true of absent mothers.) Examples include:

- Lenny’s Book Of Everything by Karen Foxlee

- Outside Over There by Maurice Sendak

- Fly Me Home by Polly Ho-Yen

- Furthermore by Tahereh Mafi

- You May Already Be A Winner by Ann Dee Ellis

- Dog-man: A tale of two kitties by Dav Pilkey

In modern children’s stories the fathers are absent for a wide variety of reasons, sometimes those reasons are left unexplained. In 20th century children’s stories the fathers are often absent because they are at war.

Into The Forest by Anthony Browne is a stand-out example of a picture book about a child’s emotional landscape as the father is away at war.

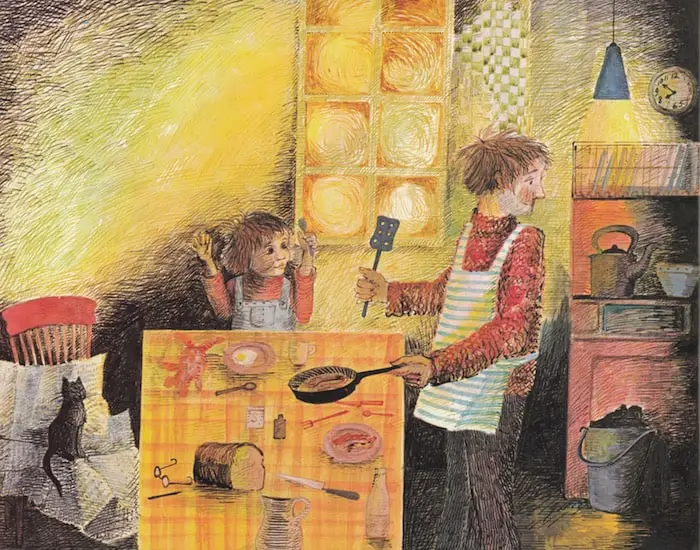

Fathers Preparing and Serving Food

It is rare to find instances of males providing food in children’s literature. One such is Will in Philip Pullman’s The Subtle Knife. Will nurtures Lyra through food, cooking an omelette for her. He has knowledge of relevant food rules and domestic hygiene practices. It could be argued, however, that Will is feminized by the role he performs, especially given that he is also earlier seen to be caring for his sick mother. Pullman’s framing of the boy as having murdered a man may serve the purpose of counteracting the feminizing effect of his implicit domestication.

Carolyn Daniel, Voracious Children

As Daniel points out, when dads serve food in children’s fiction they are often less ‘fussy’ about its presentation than the mothers. They’ll provide a meal, and sometimes the meal ends up really delicious and fun, but he’ll slap the knives and forks onto the table rather than expecting them to be laid out, as a mother might. Instead of acting in loco parentis, the dad in a story is often ‘babysitting’. In real life, too, you often hear men talking about ‘babysitting’ their own children, but women will almost never use this term when describing their own mothering duties.

Daniel does offer one example of a nurturing male who provides food in children’s literature, and that’s Michael from David Almond’s Skellig. He looks after an old man presumed to be a tramp, bringing him Chinese takeaway (but in a way that puts me right off Chinese takeaway, I must say).

Examples

- King Arthur

- Zeus

- The Tempest

- The Godfather

- Rick in Casablanca

- King Lear

- Hamlet

- Othello

- Aragorn and Sauron in The Lord of the Rings

- Agamemnon in the Iliad

- Citizen Kane

- Star Wars

- Stanley in A Streetcar Named Desire

- American Beauty

- Willy Loman in Death of a Salesman

- Fort Apache

- Meet Me In St. Louis

- Mary Poppins

- Tootsie

- The Philadelphia Story

- Red River

- Howards End

- Chinatown

To this end, it’s useful to take a look at various ‘King tropes’ when understanding the roles — the strengths and shortcomings — typical of fathers in fiction.

King Tropes

Related Links

- The Tiny Key: Unlocking the father/child relationship in young adult literature by Zu Vincent

- Fantastic Dads and Father Figures, a Goodreads List

- Books for Teens with LGBT Parents, a Goodreads List

- Picturebooks About Fathers, a Goodreads List, because publishers like to put these out into the world around fathers’ day.

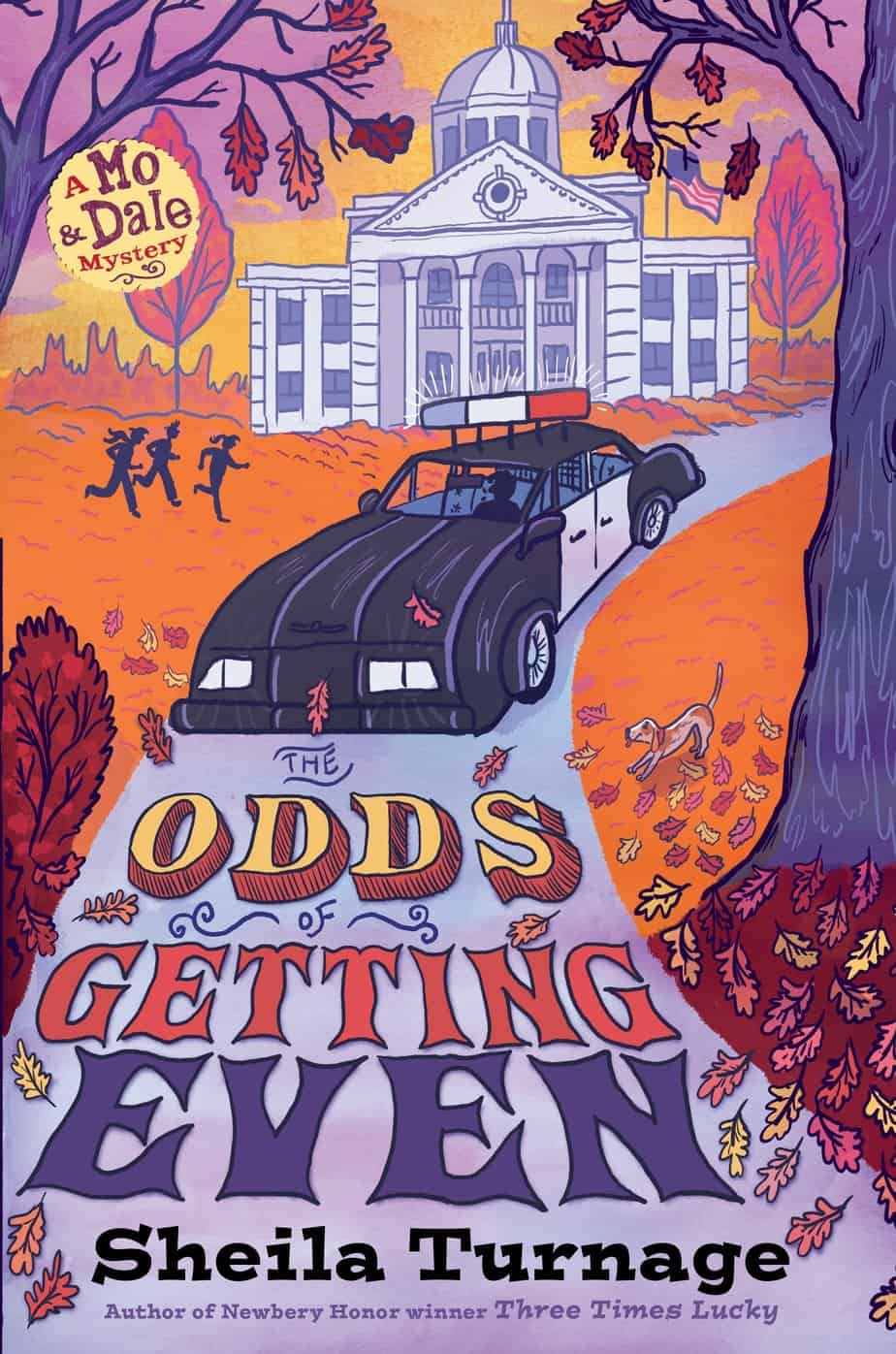

The trial of the century has come to Tupelo Landing, NC. Mo and Dale, aka Desperado Detectives, head to court as star witnesses against Dale’s daddy–confessed kidnapper Macon Johnson. Dale’s nerves are jangled, but Mo, who doesn’t mind getting even with Mr. Macon for hurting her loved ones, looks forward to a slam dunk conviction–if everything goes as expected.

Of course nothing goes as expected. Macon Johnson sees to that. In no time flat, Macon’s on the run, Tupelo Landing’s in lockdown, and Dale’s brother’s life hangs in the balance. With Harm Crenshaw, newly appointed intern, Desperado Detectives are on the case. But it means they have to take on a tough client–one they’d never want in a million years.

For everyone who’s already fallen for Mo and Dale, and for anyone who’s new to Tupelo Landing, The Odds of Getting Even is a heartwarming story that perfectly blends mystery and action with more serious themes about family and fathers, all without ever losing its sense of humor. Cover design by Gilbert Ford.

I thought the Lego film was delightful. They had a deep subtext that created a brilliant climax when you had a marvelous turning point where suddenly everything is retrospectively obvious, and there’s a massive reconfiguring of reality. Suddenly all those father characters you saw from world to world to world are all aspects of the kid’s father. It was superbly written!

Robert McKee

RETROSPECTIVE FIRST PERSON: A CHILD’S VIEW OF A FATHER

Adult fiction frequently depicts children, but usually with the reflective understanding of an adult. When we are children, our parents are just our parents. They are normal. We can’t get a rounded view of them until we are older, and more removed:

Sofia pays only a glancing attention to other adults. She notices when they enter her father’s gravitational field, and when the warmth of his attention skips from one to another. She notices that her father always seems to be the tallest in the room. She accepts the offerings of jellied candies and biscotti handed down by men who, even Sofia can tell, are more concerned with currying her father’s favor.

After his meetings Sofia’s papa takes her for gelato; they sit at the counter on Smith Street and he sips thick black espresso while she tries not to drip stracciatella down the front of her shirt. Sofia’s papa smokes long thin cigarettes and tells her about his meetings. We’re in the business of helping people, he tells Sofia. For that, they pay us a little bit, here and there. So Sofia learns: you can help people, even if they are afraid of you.

She is his girl, she knows that. His favorite. He sees himself in her. Sofia can smell the danger on her father like a dog smells a storm coming: an earthy quickening in his wake. A taste like rust. She knows that means he would do anything for her.

Sofia can feel the pulse of the universe thrumming through her at every moment. She is so alive she cannot separate herself from anything around her. She is a ball of fire and at any moment she might consume her apartment, the street outside, the park where she goes with Antonia, the church and the streets her papa drives on for work, and the tall Manhattan buildings across the water. It is all tinder.

Instead of burning the whole world Sofia contents herself with asking why, Papa, why, what is that.

from The Family, a 2022 novel by Naomi Krupitsky

Some short stories are all about the moment a child learns that their father is a rounded person. Examples:

- “Reunion” by John Cheever

- “Walker Brothers Cowboy” by Alice Munro

THE ABSENT FATHER EFFECT ON DAUGHTERS

The Absent Father Effect on Daughters: Father Desire, Father Wounds (Routledge, 2020) investigates the impact of absent – physically or emotionally – and inadequate fathers on the lives and psyches of their daughters through the perspective of Jungian analytical psychology. This book tells the stories of daughters who describe the insecurity of self, the splintering and disintegration of the personality, and the silencing of voice. Issues of fathers and daughters reach to the intra-psychic depths and archetypal roots, to issues of self and culture, both personal and collective.

Susan E. Schwartz illustrates the maladies and disappointments of daughters who lack a father figure and incorporates clinical examples describing how daughters can break out of idealizations, betrayals, abandonments and losses to move towards repair and renewal. The book takes an interdisciplinary approach, expanding and elucidating Jungian concepts through dreams, personal stories, fairy tales and the poetry of Sylvia Plath, along with psychoanalytic theory, including Andre Green’s ‘dead father effect’ and Julia Kristeva’s theories on women and the body as abject. Examining daughters both personally and collectively affected by the lack of a father, The Absent Father Effect on Daughters is highly relevant for those wanting to understand the complex dynamics of daughters and fathers to become their authentic selves. It will be essential reading for anyone seeking understanding, analytical and depth psychologists, other therapy professionals, academics and students with Jungian and post-Jungian interests.

New Books Network

Header painting: Nils von Dardel (Swedish, 1888-1943), My daughter, 1923. Watercolor on paper, 45 x 28 cm. Private collection