The Magic Porridge Pot is also known as Sweet Porridge and goes by various similar titles.

Sweet Porridge

There is a motif common in European folktales: A cooking pot that will not cease overflowing. Although this story is obviously a response to famine, I think it’s also a response to a general childhood way of thinking in which you’re not sure when things that start are going to stop. Although there were no flush toilets back in the middle ages, I still remember being wary of flushing toilets when I was a kid, never completely sure if a flushing toilet would overflow, or if a fast-running tap would ever turn off, for instance.

I am more familiar with the English title ‘The (Magic) Porridge Pot’ and you probably are too, but this fairytale was originally called ‘Sweet Porridge’ in German. Apparently it is originally Swedish.

Various Versions Of The Magic Porridge Pot

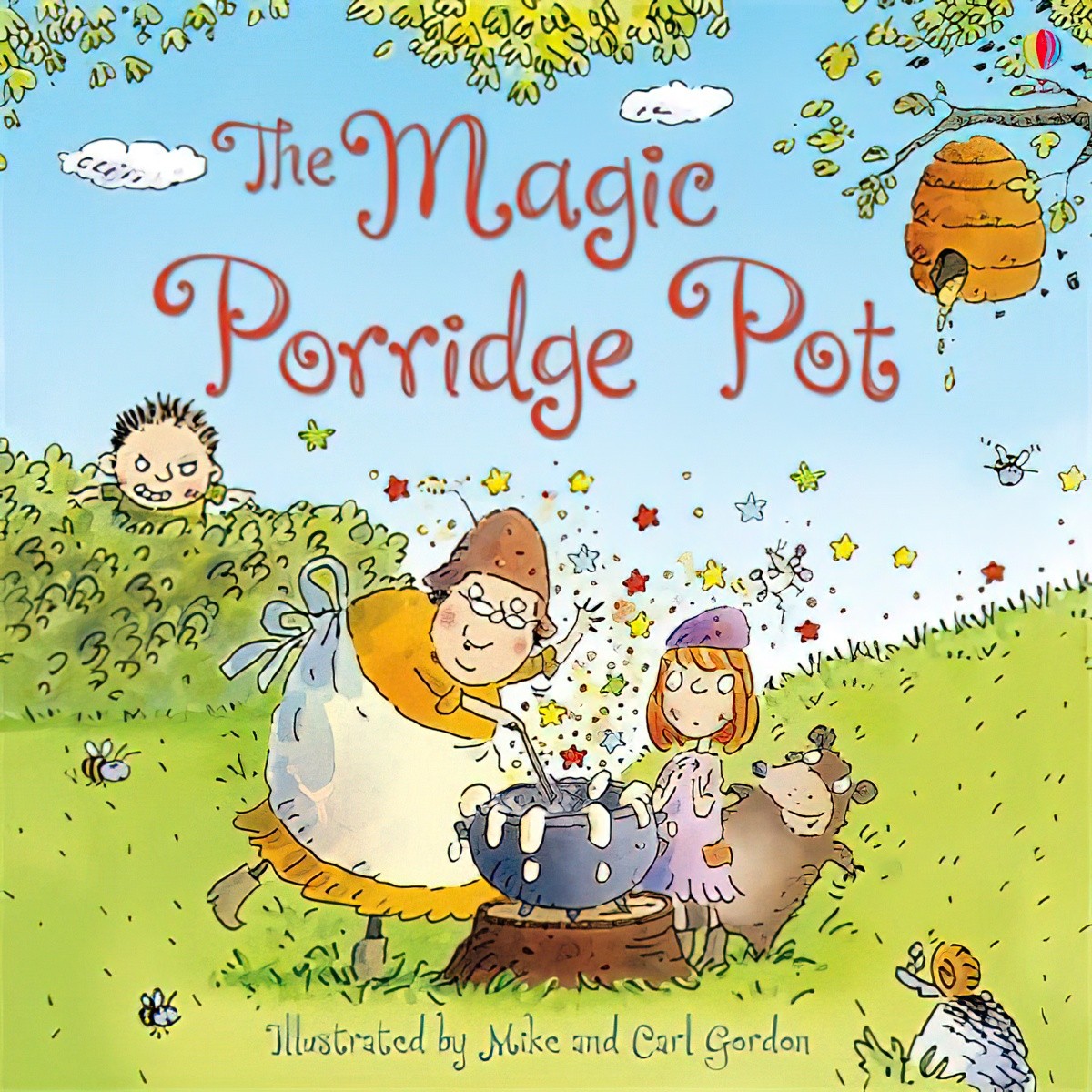

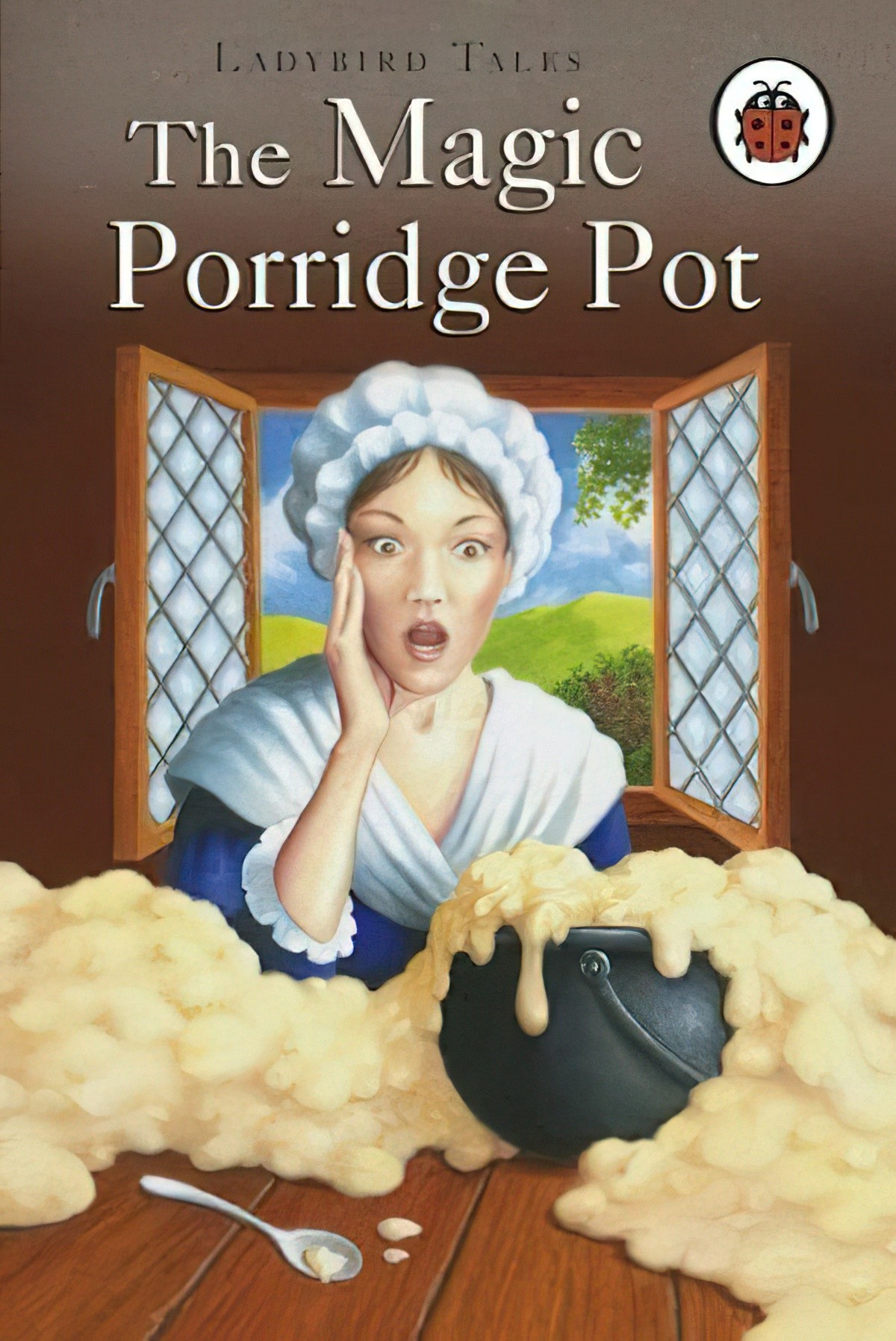

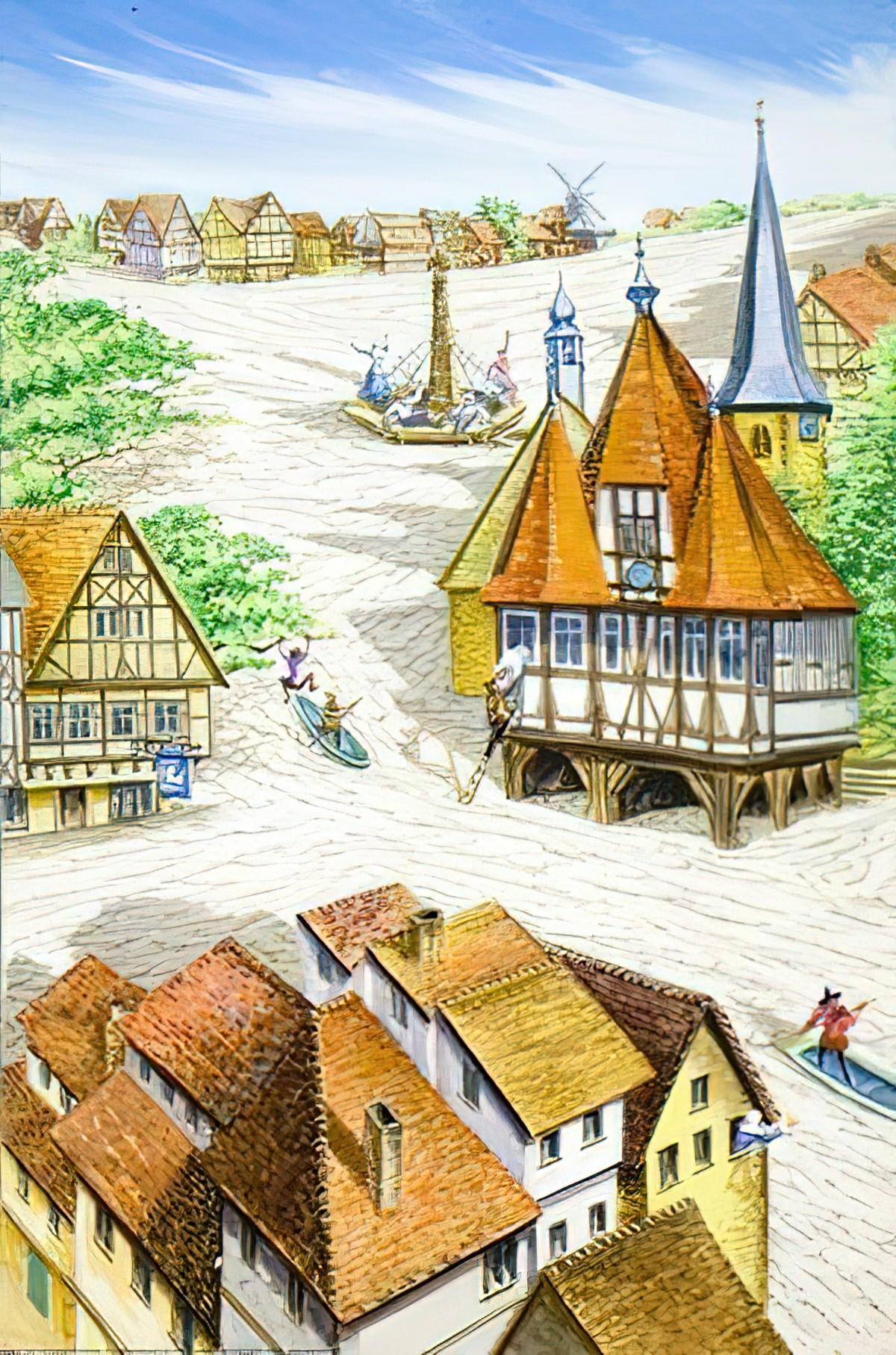

Several different Ladybird versions of this tale can be found on our shelves. They are interesting to compare because the style of illustration is so different. Most of the big children’s book titles have produced a version of The Magic Porridge Pot. Here’s an Usborne version, with its bright colours and lively black outline work:

Ladybird produced its own version in the same illustrative style:

Not just one, actually! Here we have a more subtle, watercolour style for the distant background but the cartoonish style of the characters is very similar:

Just for contrast, this takes the cake for the ugliest children’s book cover I’ve ever seen. I don’t know what they were thinking but what the actual? Is this a Magic Eye type thing? Or the underbelly of a snake?

Here’s an illustration from a more recent version of this story which appeared in a children’s magazine in 2015. The style of the characters reminds me of Japanese manga characters. It could almost be a still from a Hayao Miyazaki anime:

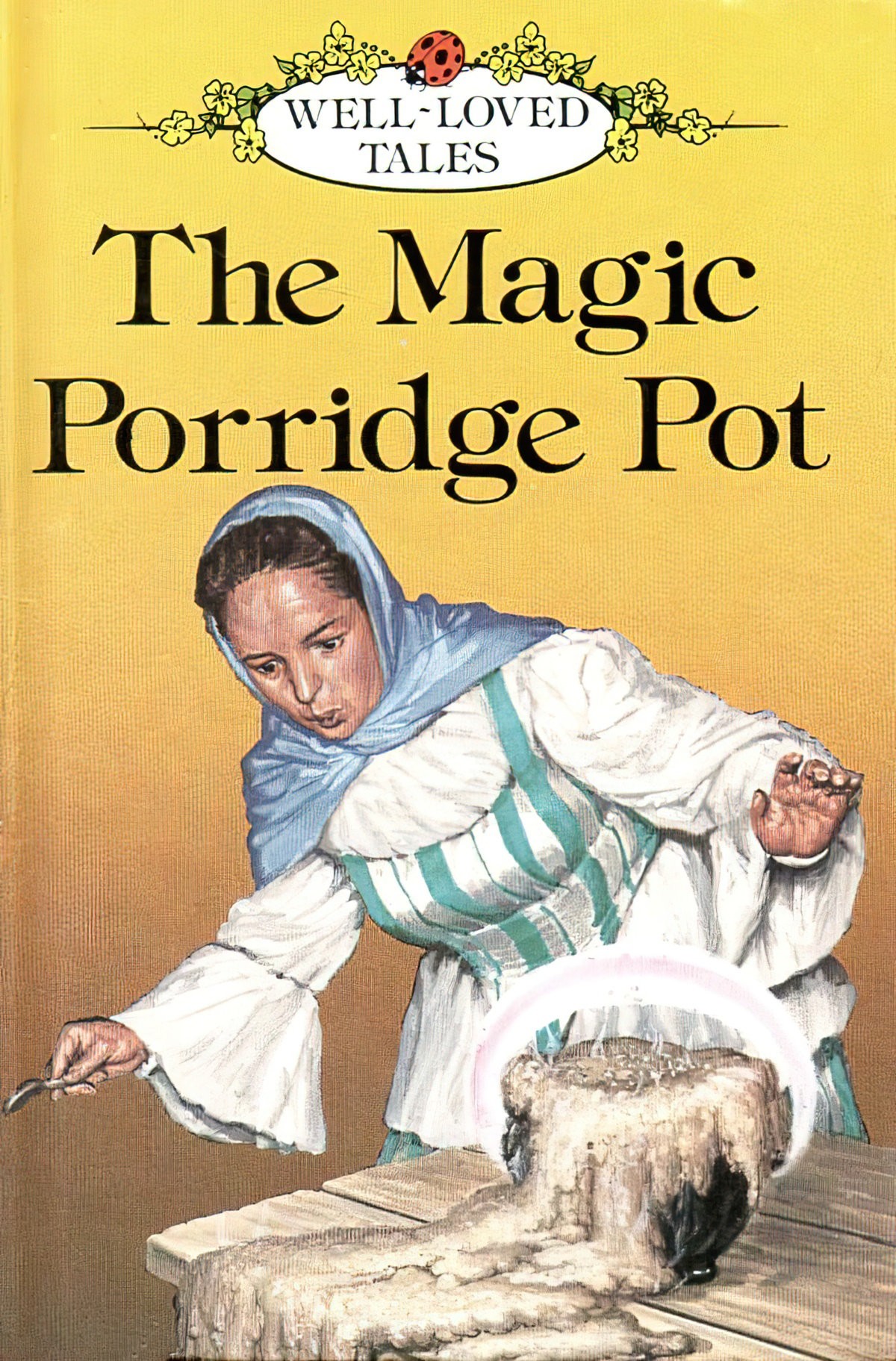

Back to the earlier versions, I’m not sure what that thing is on the mother’s head, is it a towel because she has washed her hair, or a very big bow?

In any case, these characters look like recognisable people. The cartoon characters can be pretty much anyone white, but these two look like they’ve been based on real human models. This one’s similar, though she looks like a more generic beautiful white woman:

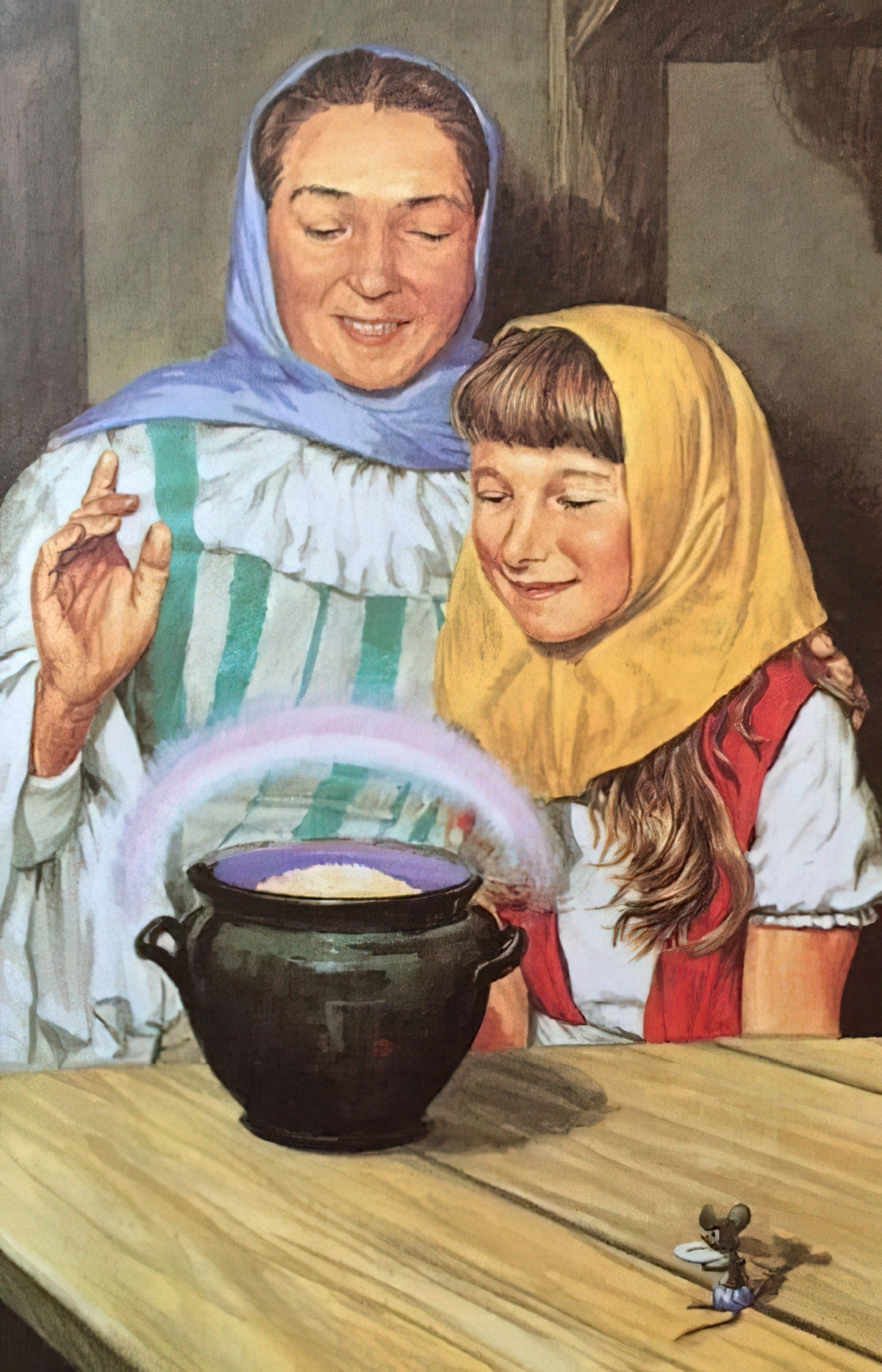

Now to my own 1971 Ladybird edition, which I like the most. It is illustrated by Londoner Robert Lumley, born 1920.

This woman looks like a specific person, doesn’t she?

This version is part of the ‘realistically illustrated’ series, all by Robert Lumley, in the decade between 1964 and 1974.

The most hilarious thing about the illustrations in these books is that they look very much ‘posed for’ and staged. “Imagine this pot on the table is overflowing,” says the artist, taking a reference photo. “Now, look surprised!”

“Look a different kind of surprised!”

“Imagine the pot is magical!”

(I’m assuming the emaciated mouse wearing pants and holding a mini plate was not posed for.)

I know I sound critical of this realistic style of illustration in these Lumley Ladybirds, but really they’re my favourite versions. While the illustrations do lack more realistic movements that can be better achieved via a cartoonish style (see the illustrations of Australian Emma Quay, especially Rudie Nudie, for a great example of characters in movement), the illustrations here are very much of a time and place — specifically old world German — which is harder to achieve in a highly cartoonish style.

“Now, you just stand over there in the background. Don’t move…”

The addition of wild animals in the frame make these photorealistic illustrations seem more ‘picturebook-like’. In the picture above, an interested rabbit.

Here we still have some off-kilter perspective — I suspect there was no reference photo for this one, or perhaps the illustrator specialises in portraits — but it absolutely does the job of conveying the quaintness of the town.

Food In Fairytales

Food is a regular component of fairy tales that have medieval oral antecedents. Famine was a frequent and devastating feature of life in Europe in the Middle Ages and deprivation inevitably shapes fantasies and desires. The magic world of fairy tales often promised rich, sweet, and plentiful food.

Carolyn Daniel, Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

STARVATION IN THE MEDIEVAL ERA

In medieval times when crops failed the poor were forced to live on: “horsse corne, beanes, peason, otes, tares & lintels.”

William Harrison’s A Description of England, 1577

horsse-corne = corn grown for horses

peason = an obsolete plural for peas

tares = any of several weedy plants that grow in grain fields

lintels = ‘lentils’ is the modern spelling

During the period 1437 to 1439, for example, “when there was a succession of wet summers and harvests were ruined, the peasantry was reduced to eating such herbs and roots as they could gather from the hedgerows, and thousands died“. The scenario in “The Sweet Porridge” reflects similarly desperate circumstances; the girl’s mother is a widow, so the earning capacity of the husband/father figure has been lost and the girl is presumably searching for something edible in the woods. It is not hard to understand how such persistent hunger and hopeless conditions could lead to a fantasy such as a magic porridge pot. It is not so much what is eaten that is at issue when you are starving but that there should be sufficient of whatever there is to eat. Good, sweet porridge, and plenty of it, could fulfill that desire. “The Sweet Porridge” is thus a story that relies upon habitual and chronic hunger as a driving force.

Carolyn Daniel, Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

In fact, even those who lived in castles couldn’t afford to withstand a famine back then, at least in what’s now known as The Great Famine (1315-1317). The human population in Europe was exceeding the ability for land to provide food, except in years with bumper crops. Other impacts of starvation:

- Sometimes elderly people would sacrifice eating in order to let the younger ones pull through.

- Some churchgoers started to realise that no amount of prayer would provide food and church attendance dropped during times of famine.

- The Black Death actually helped fixed the starvation crisis, since the population was greatly reduced. But famine was still a great threat.

- Most people would go through 3-4 famines in their lifetimes during the middle ages.

In the Middle Ages, rich people ate what today could best be compared to Sally Fallon and Mary Enig’s Nourishing Traditions diet, with plenty of meat, poultry and saturated fats, with fermented grains and unpasteurised dairy products. But poor people ate whatever they could get their hands on, with porridge being cheap, along with bread made from barley and rye. Poor people drank ale, similar to beer. Barley was eaten at every meal. The poor drank water and mixed it with honey if they could. This is not so different from what poor people eat today: grain products and lots of fructose.

Compare and Contrast With The Magic Porridge Pot

When it comes to food fantasy in folk tales, Hansel and Gretel is the stand-out example, to the point you can’t now put a witch in a forest without the audience thinking of this famous tale.

Versions of The Magic Porridge Pot story can also be found in other cultures. For example West Kalimantan (Indonesia) has a folktale called Why Rice Grains Are So Small.

Tomie dePaola wrote a tale called Strega Nona, published in 1975, a modern version of The Magic Porridge Pot in which there is an overflowing magic pasta pot. This is probably dePaola’s best known work. It is set in Italy, of course. dePaola created the character of Strega Nona (Grandma Witch) himself, even though she sounds like she’s borrowed from folklore.

The coming food riots of the twenty-first century from io9

With So Much Food, Why Do So Many People Go Hungry? from Freakonomics

What Happens When You Stop Eating from Hank Green (of Vlog Brothers)

What’s it like to live on ‘soylent’ for 30 days? from The Dish

Header illustration: Arkady Sher